Abstract

Hepatitis B in pregnancy must include diagnosis and management of the pregnant woman as well as modalities to decrease mother to child transmission (MTCT). MTCT remains the most important mode of hepatitis B virus (HBV) transmission, although effective strategies exist to reduce this risk. Universal screening for HBV can identify women with previously unrecognized infection and allow for targeted therapy to prevent MTCT. All children of HBV-infected mothers should receive passive active immunoprophylaxis with hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) and HBV vaccination within 12 h of birth. With such measures, the risk of transmission can be decreased to less than 1 % in women with low viral loads. Immunoprophylaxis failures occur in as many as 15 % of children born to mothers with high viral loads at the time of delivery (>6 log copies/ml or >200,000 IU/ml), and therefore, additional treatment in the third trimester is warranted in this group. Antiviral therapy with lamivudine, tenofovir, or telbivudine in the third trimester can decrease MTCT to less than 5 % and should be used in women with high viral loads in the third trimester. Postpartum flares of liver disease are common, and therefore, careful monitoring is warranted in women who stop therapy. The decision to breastfeed while on antiviral therapy should be individualized, but current evidence suggests that it is safe.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection remains an important global health problem, with greater than 300 million people with chronic infection worldwide. Globally, mother to child transmission (MTCT) remains the most common mode of infection, especially in areas of high endemicity, where approximately 10 % of women of childbearing potential are chronically infected [1]. It is critical that pregnant women with HBV infection are diagnosed and properly managed through pregnancy, since timely pre- and peripartum management can decrease vertical transmission from >90 % to less than 5 % [2, 3]. This review article will focus on the management of the HBV-positive female prior to, during, and after pregnancy.

Before Conception

Providers should initiate discussions about pregnancy in women of childbearing age with chronic hepatitis B because there are implications in timing and choice of antiviral therapy. Although many young women are in the immunotolerant phase of disease and do not warrant antiviral therapy for themselves, others may have liver inflammation, fibrosis, and high viral loads and meet current guidelines for treatment (Table 1) [4]. If treatment is not urgently required (persistent mild liver enzyme elevation (2× ULN, i.e., ~40–50 U/ml) but little or no fibrosis), providers should discuss timing of antiviral initiation. It may be reasonable to consider waiting to initiate therapy once childbearing is complete or a stronger need for antiviral therapy arises. If a woman requires HBV antiviral therapy and plans to become pregnant in the future, it is advantageous to start her on therapy that can be continued through pregnancy. In this circumstance, tenofovir is preferred because it is safe in pregnancy, potent, and has low risk for resistance with long-term use.

Although lamivudine (pregnancy class C), telbivudine, and tenofovir (both pregnancy class B) are considered to be safe in pregnancy (Table 2), only tenofovir is recommended as a first-line therapy outside of pregnancy. Interferon should not be used in pregnancy (pregnancy class C). The antiretroviral pregnancy registry (APR, available online at http://www.apregistry.com) is a prospective, observational study examining the influence of antiretroviral use during pregnancy. The majority of women followed in this registry are HIV infected; however, a minority of women with HBV on antivirals are also included. As of the most recent update from December 2014, this registry includes pregnancy outcomes on 2383 women exposed to tenofovir, 4485 women exposed to lamivudine, and ten women exposed to telbivudine. Rates of congenital malformation were not found to be higher than that of the general population (Table 2) [5–10]. Of the antivirals that are effective for HBV but not recommended in pregnancy, there are limited data on adefovir and entecavir (pregnancy class C) included in this registry: animal models have reported reproductive and embryo-fetal toxicity and therefore should not be used during pregnancy. If a woman is on entecavir or adefovir and wishes to become pregnant then she should be changed to tenofovir prior to conception.

The current body of evidence suggests that tenofovir appears to be safe in pregnancy. A recent systematic review has examined both animal and human studies of tenofovir exposure during pregnancy [11]. Among animal studies included in the review, no evidence of impaired fetal growth from high-dose tenofovir exposure in utero was identified [12, 13], though postnatal high-dose administration was associated with growth restriction and decreased bone porosity [14]. There are limited human data on the effect of in utero exposure to tenofovir and bone health. A case series of 15 children with intrauterine tenofovir exposure found normal growth at 1 year on 14/15 children [15], and a small multicenter observational study found no evidence of impaired growth after a median follow-up of 23 months [16]. The largest observational data on tenofovir in pregnancy to date originates from the US Pediatric HIV/AIDS Cohort Study (PHACS). A retrospective analysis of the 449 children with in utero tenofovir exposure showed an association between tenofovir and impaired growth at 1 year (length for age Z-score: −0.17 vs −0.03, p = 0.04; head circumference for age Z-score: 0.17 vs 0.42, p = 0.02) [17]. It is unclear whether this growth delay persists beyond 1 year, and whether in utero exposure to tenofovir has long-term implications on bone health.

Telbivudine is not used for management of HIV, nor is it first line therapy for HBV. Since 2006, data in HBV mono-infected women collected in the APR showed no adverse fetal outcomes in the ten women observed. Additionally, a recent observational study of 54 children with in utero exposure to telbivudine and followed for at least 1 year found no evidence of increased rates of congenital anomalies or developmental delay [18].

First and Second Trimesters

Current guidelines recommend that all pregnant women be screened for HBV infection in the first trimester [4, 19]. A number of asymptomatic women discover that they have HBV via this screening protocol. For women with newly discovered HBV infection, it is appropriate to order the routine baseline tests that one would order outside of pregnancy. These include HBV viral load, HBe antigen, and HBe antibody, HIV screen, HCV and HDV antibodies, and liver enzymes. First-degree family members should be screened for HBV and be vaccinated if not immune. The ability to screen for advanced fibrosis that would warrant antiviral therapy before the third trimester is limited. Liver biopsy is contraindicated and fibroscan is not approved for use in pregnancy. Platelets can occasionally be decreased in otherwise normal pregnant women [20], making non-invasive measures of advanced fibrosis inaccurate. However, it is important to estimate fibrosis after delivery.

In women with previously diagnosed HBV infection who become pregnant, no additional HBV specific testing is required in the first trimester. Women receiving antiviral therapy should have been switched to tenofovir prior to conception as discussed above. If not, pregnant patients should be switched as soon as possible to tenofovir. Discontinuation of antiviral therapy in pregnancy can be associated with viral reactivation and flares, which in some cases can be severe (defined as increase in liver enzymes to five times the upper limit of normal). In one small study, 50 % of patients had reactivation after stopping therapy, although decompensation was rare [21]. Patients with significant fibrosis prior to conception are at risk for deterioration and antiviral discontinuation is not advised. For women without baseline fibrosis, the decision to discontinue therapy should be individualized, although the evidence suggests that antiviral exposure to tenofovir in the first and second trimesters is safe (Table 1). For these reasons, discontinuing antiviral therapy in women with established need outside of pregnancy is discouraged.

Patients should continue routine follow-up with their primary care physician and obstetrician throughout pregnancy. Some providers recommend ALT and HBV DNA every 1–3 months, but in the absence of active disease or advanced fibrosis, there is no need for additional follow-up specifically for HBV until the third trimester.

Intrauterine Transmission

Most MTCT occurs around the time of delivery; however, there are data to suggest that intrauterine HBV infection may also occur, possibly through placental infection [22–26]. It is theoretically possible to transmit infection through amniocentesis; however, the overall risk is low, especially in those with low HBV DNA [27]. One case-control study suggests a possible increase in MTCT rates in women with high viral loads undergoing amniocentesis (among women with ≥7 log copies/ml: vertical transmission 50 vs 4.5 % in controls without amniocentesis, p = 0.006) [28]; however, additional studies are warranted before treatment recommendations can be made.

Third Trimester Management to Prevent MTCT

All women should have HBV DNA levels drawn at 26–28 weeks of gestation. HBeAg positivity and high maternal HBV DNA at the time of delivery are associated with increased risk of vertical transmission of HBV. Women of childbearing age are often in the immune tolerant phase of disease and will be HBe antigen positive with high viral loads and are therefore at increased risk for MTCT. All infants born of women with chronic hepatitis B infection should obtain immunoprophylaxis with hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) and HBV vaccination within 12 h of birth. For many women, no additional measures are required. However, women with high viral loads (>106 copies/ml or >200,000 IU/ml) in the third trimester are at higher risk for transmission despite immunoprophylaxis, with immunoprophylaxis failure rates as high as 8–15 % [29, 30]. These women warrant additional therapy to further decrease the chance for MTCT.

Targeted antiviral therapy in the third trimester can reduce the rate of MTCT in women with high HBV viral loads. Therapy should be initiated between 28 and 32 weeks to allow for sufficient time for DNA levels to decrease, and reduce the risk of HBV transmission. Lamivudine, telbivudine, and tenofovir have all been studied in prevention of MTCT. Lamivudine has the largest body of evidence supporting its use. A meta-analysis of 15 RCTs looking at the impact of lamivudine in the third trimester included 1693 women with HBV infection. This analysis found that transmission was significantly reduced with lamivudine with an overall risk of 0.43 (95 % CI, 0.25–0.76) [31]. Of note, significant heterogeneity existed in lamivudine administration and control arm characteristics. In subgroups with very high viral loads, this result was attenuated (RR 0.61, 0.25–1.52 in four RCTs, p = 0.29), perhaps due to slower decrease of HBV DNA on lamivudine and insufficient time for viral loads to decrease sufficiently prior to delivery. Lamivudine has relatively low potency, decreasing HBV DNA less rapidly than tenofovir and there exists potential for resistance mutations, especially in women with high viral load. Evidence is mounting that tenofovir is a safe and efficacious alternative to lamivudine for prevention of MTCT and is preferred as it is more potent, has faster decline in HBV DNA, and no resistance reported as yet.

Until recently, evidence for use of tenofovir for prevention of MTCT arose from case series and retrospective observational studies [32–34]. A recent study from Australia is the first prospective, controlled study to demonstrate the safety and efficacy of tenofovir in prevention MTCT [35••]. A total of 130 pregnancies in 120 women with high viral load (>7 log ± 0.5 IU/ml) were included in this analysis. Women were offered antiviral therapy starting at week 32. Those who chose not to initiate antiviral therapy were followed in the control arm. From 2007 to 2010, lamivudine 100 mg daily was prescribed and from late 2010 onwards, tenofovir was offered. A total of 58 women received tenofovir, 52 women received lamivudine, and 20 women received no antiviral therapy. All infants received immunoprophylaxis. Tenofovir was overall well tolerated, although four women switched to lamivudine early in antiviral therapy because of GI intolerance ascribed to tenofovir, two of whom also had dyspnea. All symptoms resolved after switching to lamivudine. Tenofovir use was associated with a greater HBV viral load decline at delivery (drop by 3.45 log) as compared to lamivudine (2.12 log drop). Obstetrical and infant outcomes did not differ between groups. Among infants tested for HBsAg at 9 months of age, no MTCT occurred in the lamivudine group (0/43); one event occurred in the tenofovir group (1/43) despite adequate viral load suppression (4.42 log IU/ml at delivery), adherence to antiviral therapy and immunoprophylaxis; and two events occurred in the control group (2/9) (p = 0.03), suggesting that both lamivudine and tenofovir decrease vertical transmission of HBV.

Telbivudine is an alternative option for the prevention of MTCT. A number of studies suggest that it is effective and safe in pregnancy [36–38], though long-term data are lacking. In the largest open-label study to date, Zhang et al. prospectively enrolled 700 women with HBV DNA >6 log copies/ml receiving telbivudine (n = 263), lamivudine (n = 55), or no prophylaxis (n = 374), based on patient preference [39••]. Antiviral therapy was started between weeks 28 and 30. All infants received immunoprophylaxis within 6 h of birth and HBV vaccination. Six hundred forty-eight women were followed for the full duration (52 weeks). The mean decline in HBV DNA was >4 log for telbivudine and >3 log for lamivudine. Treatment was overall well tolerated, although 1.5 % of women receiving telbivudine (n = 4) had asymptomatic mild creatinine kinase elevations. Fetal outcomes, including rates of congenital abnormalities, were similar between groups. Among the infants who completed follow-up, no vertical transmission was seen in the treated group by on-treatment analysis (vs 2.84 % in the control, p = 0.002). By intention to treat, a lower rate of MTCT was still seen in the antiviral group compared to control (2.2 vs 7.6 %, p = 0.001). Failure rates did not differ significantly based on antiviral therapy used (telbivudine 1.9 % (5/262) vs lamivudine 3.7 % (2/54) by ITT; no failures in either arm by on-treatment analysis).

Peripartum

The majority of vertical transmission of HBV occurs around the time of delivery. Guidelines from the CDC and major societies (AASLD, EASL, and APASL) have recommended that children born from mothers infected with HBV be given passive active immunoprophylaxis (HBIG as well as HBV vaccination series), regardless of maternal HBV DNA or HBeAg/Ab status [40]. HBIG and the first vaccination should be given within 12 h of birth, the second vaccine at 4–8 weeks of age and the third at 3 or 6 months. Children should be screened for HBV infection between 9 and 12 months of age [40]. Transient viremia and surface antigen positivity is common in babies born of HBV-positive mothers (up to 25 % in some studies), regardless of antiviral treatment status and maternal HBV DNA at the time of delivery [39••]. As such, without HBIG, there exists a significant risk for vertical transmission in the peripartum period, regardless of antiviral use.

Interestingly, antiviral studies that administered immunoprophylaxis within 12 h of delivery found that HBIG/vaccine failures had higher maternal viral load cut-offs (>7 log copies/ml) [41] than antiviral studies that administered prophylaxis within 24 h (>6 log copies/ml) [37, 42], highlighting the importance of early immunoprophylaxis with HBIG and the first dose of HBV vaccine. A recent study from Yunnan Province in China emphasizes the importance of HBIG and vaccination showing higher rates of transmission when infant was not vaccinated within 24 h (transmission rates 11.11 vs 3.98 %, p < 0.05) or did not receive HBIG (6.99 vs 2.83 %, p < 0.001) [43]. Additionally, a retrospective database analysis of 4446 infants born to mothers with hepatitis B surface antigenemia in the Kaiser Permanente (KP) Northern California system had an overall vertical transmission rate of 0.75 %. In this large analysis, 87 % of infants received immunoprophylaxis within 12 h of birth, demonstrating that designing a system to administer prompt treatment of infants born to HBV-positive mothers is effective in decreasing perinatal transmission of HBV [44]. All immunoprophylaxis failures (3/835 children with positive HBsAg at 9 months of age) occurred in women with high viral loads (>50,000,000 IU/ml), reaffirming the need for maternal therapy in the third trimester for women with high viral loads, in addition to neonatal immunoprophylaxis.

At the present time, there is insufficient evidence to recommend caesarean section for HBV prevention in women with high viral loads at the time of delivery, especially given that third-trimester antiviral initiation is an excellent method to reduce maternal viral loads at delivery and is an effective adjunct to immunoprophylaxis for prevention of MTCT. A recent meta-analysis of ten studies showed decreased odds of transmission with caesarean section (OR 0.62 [95 % CI 0.40–0.98]) [45]; however, significant heterogeneity within studies existed relating to HBIG administration (63 %, p = 0.003). Of note, meta-regression showed minimal benefit of caesarean section in studies with 100 % HBIG administration, suggesting that mode of delivery may not significantly impact transmission rates when appropriate measures including antiviral therapy and immune prophylaxis with HBIG and vaccination are undertaken.

Postpartum Care

Women who have an indication for treatment apart from pregnancy should continue on antiviral therapy. If a woman was placed on antiviral therapy solely for the purpose to decrease perinatal transmission, therapy can be discontinued postpartum. Most studies of antiviral use to prevent MTCT continue antivirals for 4–12 weeks after delivery. HBV flares can occur in the postpartum period, thought to be due to immune reconstitution after the relative immune-tolerance of the pregnant state [46•]. These flares occur regardless of antiviral exposure and do not appear to be prevented by longer antiviral use postpartum. A recent observational study of 101 pregnancies in women with HBV treated with either lamivudine, tenofovir, or no antiviral (based on patient preference) sought to describe prevalence and severity of postpartum flares. Forty-four women were included in the early cessation group (median 2 weeks), 43 in the late cessation (median 12 weeks), and 14 in the natural history arm. Postpartum flare rates were numerically higher in the antiviral therapy groups (50 % early, 40 % late, vs 29 % untreated), though this did not achieve statistical significance. No clinical parameters were found to predict postpartum reactivation. The severity of the flare/reactivation was not significantly different between groups (median ALT peak 229.5 U/l early, 209.0 U/L late, 310.5 U/L untreated), with the onset of flares at 8.2–10.2 weeks postpartum. Among women who flared, most resolved spontaneously (75 % early, 53 % late, 75 % untreated) after 18–25 weeks duration. A minority of patients required antiviral therapy for treatment of flare. Similarly, another observational study of 126 women with HBV followed through pregnancy found that 25 % of women had a postpartum flare, defined as two times the upper limit of normal ALT [47]. Most of the women included in this analysis were not taking antiviral medications during pregnancy. On univariable analysis, age, HBeAg status, and multiparity were associated with flare; however, none of these factors were significant in multivariable analysis.

Thus, all patients should be monitored in the postpartum setting for disease flare. If HBV flare is persistent or severe, initiation, or re-initiation of antiviral therapy should be considered. Use or length of antiviral therapy in the postpartum period does not impact the incidence nor severity of flare, and therefore, the duration of postpartum therapy should be dictated by individual patient characteristics including desire to breastfeed.

Breastfeeding

Current guidelines and drug package inserts recommend that women on antiviral therapy abstain from breastfeeding. The evidence to support this practice is limited. There are accumulating data to suggest that tenofovir and lamivudine are safe in breastfeeding, and WHO guidelines support their use in resource-poor settings for women with HIV infection [48]. Currently, no data exists on the safety of breastfeeding with telbivudine use. A recent review article has summarized the data on breastfeeding and antiviral use in HBV [49•]. Lamivudine freely crosses the placenta and also is concentrated and excreted in breast milk [50–55]. Despite this, antiviral blood concentrations in breastfeeding neonates decrease over time, suggesting that lamivudine is either inefficiently absorbed by the newborn or that the total amount of lamivudine ingested from breast milk is negligible [56–58]. Tenofovir also crosses the placenta, but less freely than lamivudine. Both animal and human studies demonstrate that tenofovir concentrations are lower in breast milk than in maternal serum or cord blood [59]. Animal studies have failed to show toxicity in breastfeeding infants at supratheraputic doses [60]. Human studies have shown that overall the amount of tenofovir ingested by the infant would be 0.03 % of the recommended neonatal treatment dose [49•]. These data suggest that overall exposure to lamivudine or tenofovir is much higher in utero than from breast milk. Given that third-trimester antiviral use has a good safety profile and this targeted use is endorsed, it is illogical to recommend against its use when breastfeeding, as any additional exposure via breast milk is negligible. That being said, if a patient plans to breastfeed and she does not have an indication outside of pregnancy to be on HBV therapy, antiviral therapy should be discontinued. Patients may choose to start breastfeeding immediately after delivery given the very low infant bioavailability of tenofovir and lamivudine or alternatively may choose to pump for 2–3 days and discard breast milk to ensure that antiviral concentrations in breast milk are negligible. On the other hand, if a woman has a strong reason to remain on treatment and would like to breastfeed, she should be informed of the known and unknown risks of antiviral use during breastfeeding so that she is able to make an educated decision. Of note, HBV transmission is rare from breastfeeding alone [61] and therefore should not factor into the decision of whether or not to breastfeed.

Lastly, an important and often overlooked issue is that patients diagnosed with hepatitis B during pregnancy require ongoing follow-up for this chronic disease. HBV is associated with increased risk for cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, and these women require ongoing follow-up and care, not only during pregnancy but lifelong. A recent study suggests that fewer than half of women with HBV diagnosed in pregnancy obtained specialist follow-up and overall only 19 % had appropriate laboratory tests for monitoring HBV at 1 year postdiagnosis [62]. Thus, it is essential that postpartum follow-up is arranged and that patients obtain routine monitoring and HCC surveillance, as appropriate, according to major societal guidelines such as AASLD, EASL, or APASL.

Conclusions

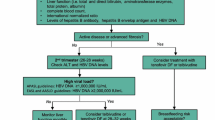

Vertical transmission can be effectively prevented with appropriate perinatal care of women infected with hepatitis B (Fig. 1). All infants born of HBV positive women should receive HBIG and vaccination within 12 h of birth. Antiviral treatment with medications approved for use in pregnancy (lamivudine, tenofovir, or telbivudine) should also be utilized for women with high viral loads in the third trimester (>200,000 IU/ml). With these measures, HBV mother to child transmission can be decreased to less than 3 %, even in high-risk subgroups. For women with treatment indications separate from their pregnancy (immune-active disease or fibrosis), tenofovir is preferred. It is imperative to ensure that all patients obtain long term clinical follow-up and undergo appropriate surveillance after delivery.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Zhang Y, Fang W, Fan L, Gao X, Guo Y, Huang W, et al. Hepatitis B surface antigen prevalence among 12393 rural women of childbearing age in Hainan Province, China: a cross-sectional study. Virol J. 2013;10:25.

Beasley RP, Hwang LY, Lee GC, et al. Prevention of perinatally transmitted hepatitis B virus infections with hepatitis B virus infections with hepatitis B immune globulin and hepatitis B vaccine. Lancet. 1983;2:1099–102.

Lee C, Gong Y, Brok J, Boxall EH, Gluud C. Effect of hepatitis B immunisation in newborn infants of mothers positive for hepatitis B surface antigen: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2006;332:328–36.

Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology. 2009;50:1–36.

Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry Steering Committee. Interim report. December 2014. 05 03 2015 <http://www.APRegistry.com>.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Metropolitan Atlanta Congenital Defects Program 6-digit code defect list. To access an electronic copy of the code list, go to http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/birthdefects/MACDP.html.

Correa-Villasenor A, Cragan J, Kucik J, O’Leary L, Siffel C, Williams L. The Metropolitan Atlanta Congenital Defects Program: 35 years of birth defects surveillance at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Birth Defects Res Part A. 2003;67:617–24.

Correa A, Cragan J, Kucik J, et al. Metropolitan Atlanta Congenital Defects Program 40th Anniversary Edition Surveillance Report: reporting birth defects surveillance data 1968–2003. Birth Defects Res Part A. 2007;79:65–93. Erratum: 2008;82:41–62.

Riehle-Colarusso T, Strickland MJ, Reller MD, Mahle WT, Botto LD, Siffel C, et al. Improving the quality of surveillance data on congenital heart defects in the Metropolitan Atlanta Congenital Defects Program. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2007;79:743–53.

Texas Birth Defect Surveillance System. Report of birth defects among 2000–2009 deliveries. Birth Defects Epidemiology & Surveillance, Texas Department of State Health Services. Published February 2012. Available from URL: http://www.dshs.state.tx.us/birthdefects/data/BD_Data_00-09/Report-of-Birth-Defects-Among-2000---2009-Deliveries.

Wang L, Koutis A, Elington S, Legardy-Williams J, Bulterys M. Safety of tenofovir during pregnancy for the mother and fetus: a systematic review. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:1773–81.

Tarantal AF, Castillo A, Ekert JE, Bischofberger N, Martin RB. Fetal and maternal outcome after administration of tenofovir to gravid rhesus monkeys. J Aquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;29:207–20.

Tarantal AF, Marthas ML, Shaw JP, Cundy K, Bischofberger N. Administration of 9-[2-(R)-(phosphonomethoxy) propyl]adenine (PMPA) to gravid and infant rehesus macaques(Macca mulatta): safety and efficacy studies. J Acquir Defic Syndr Hum Retroviro. 2000;20:323–33.

Van Rompay KK, Brignolo LL, Meyer DJ, et al. Biological effects of short-term or prolonged administration of 9-[2-(R)-(phosphonomethoxy) propyl]adenine (tenofovir) to newborn and infant rhesus macaques. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:1467–87.

Nurutdinova D, Onen NF, Hayes E, Mondy K, Overton ET. Adverse effects of tenofovir use in HIV-infected pregnant women and their infants. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42:1581–5.

Vigano A, Mora S, Giacomet V, et al. In utero exposure to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate does not impair growth and bone health in HIV-uninfected children born to HIV-infected mothers. Antivir Ther. 2011;16:1259–66.

Silberry GK, Williams PL, Mendez H, et al. Safety of tenofovir use during pregnancy: early growth outcomes in HIV-exposed uninfected infants. AIDS. 2012;26(9):1151–9.

Zeng H, Cai H, Wang Y, Shen Y. Growth and development of children perinatally exposed to telbivudine administered for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B in their mothers. Int J Infect Dis. 2015;33:e97–101.

European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2012;57:167–85.

Burrows RF, Kelton JG. Thrombocytopenia at delivery: a prospective survey of 6,715 deliveries. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;162:731–4.

Kim HY, Choi JY, Park CH, Jang JW, Kim CW, Bae SH, et al. Outcomes after discontinuing antiviral agents during pregnancy in women infected with hepatitis B virus. J Clin Virol. 2013;56:299–305.

Chen Y, Wang L, Xu Y, Liu X, Li S, Qian Q, et al. Role of maternal viremia and placental infection in hepatitis B virus intrauterine transmission. Microbes Infect. 2013;15:409–15.

Lin HH, Lee TY, Chen DS, Sung JL, Ohto H, Etoh T, et al. Transplacental leakage of HBeAg-positive maternal blood as the most likely route in causing intrauterine infection with hepatitis B virus. J Pediatr. 1987;111:877e881.

Lucifora G, Calabro S, Carroccio G, Brigandi A. Immunocytochemical HBsAg evidence in placentas of asymptomatic carrier mothers. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;159:839e842.

Bhat P, Anderson DA. Hepatitis B virus translocates across a trophoblastic barrier. J Virol. 2007;81:7200e7207.

Elefsiniotis S, Tsoumakas K, Papadakis M, Vlachos G, Saroglou G, Antsaklis A. Importance of maternal and cord blood viremia in pregnant women with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Eur J Intern Med. 2011;22:182e186.

Lopez M, Coll O. Chronic viral infections and invasive procedures: risk of vertical transmission and current recommendations. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2010;28(1):1.

Yi W, Pan CQ, Hao J, Hu Y, Liu M, Li L, et al. Risk of hepatitis B virus vertical transmission after amniocentsis in mothers with chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2013. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2013.11.008.

Zou H, Chen Y, Duan Z, Zhang H, Pan C. Virologic factors associated with failure to passive-active immunoprophylaxis in infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers. J Viral Hepat. 2012;19:e18–25.

Xu WM, Cui YT, Wang L, Yang H, Liang ZQ, Li XM, et al. Lamivudine in late pregnancy to prevent perinatal transmission of hepatitis B virus infection: a multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Viral Hepat. 2009;16:94–103.

Han L, Zhang H-W, Xie J-X, Zhang Q, Wang H-Y, Cao G-W. A meta-analysis of lamivudine for interruption of mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B virus. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(38):4321–33. doi:10.3748/wjg.v17.i38.4321.

Pan CQ, Liu M, Cai H, Yo W. Safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) treatment for the entire pregnancy in mothers with active chronic hepatitis B or cirrhosis [abstract]. Hepatology. 2013;58:624A.

Pan CQ, Mi LJ, Bunchorntavakul C, Karsdon J, Huang WM, Singhvi G, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for prevention of vertical transmission of hepatitis B virus infection by highly viremic pregnant women: a case series. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:2423–9.

Tsai Pai-Jong S, Chang A, Yamada S, Tsai N, Bartholomew L. Use of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in highly viremic hepatitis B mono-infected pregnant women. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:2797–803.

Greenup AJ, Tan PK, Nguyen V, Glass A, Davison S, Chatterjee U, et al. Efficacy and safety of tenofovir tisoproxil fumarate in pregnancy to prevent perinatal transmission of hepatitis B virus. J Hepatol. 2014;61:502–7. First prospective, controlled study to demonstrate the safety and efficacy of tenofovir in prevention MTCT in women with high viral load (>7 log copies/ml).

Han GR, Cao MK, Zhao W, Jiang HX, Wang CM, Bai SF, et al. A prospective and open-label study for the efficacy and safety of telbivudine in pregnancy for the prevention of perinatal transmission of hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2011;55:1215–21.

Pan CQ, Han GR, Jiang HX, Zhao W, Cao MK, Wang CM. Telbivudine prevents vertical transmission from HBeAg-positive women with chronic hepatitis B. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:520–6.

Liu M, Cai H, Yi W. Safety of telbivudine treatment for chronic hepatitis B for the entire pregnancy. J Viral Hepat. 2013;20:S1:65–70.

Zhang H, Pan CQ, Pang Q, Tian R, Yan M, Liu X. Telbivudine or lamivudine use in late pregnancy safely reduces perinatal transmission of hepatitis B virus in real-life practice. Hepatology. 2014;60(2):468–76. Largest prospective study to date of telbivudine for prevention of MTCT of HBV in women with high viral load (>6 log copies/ml).

Mast R, Margolis H, Fiore A, Brink E, Goldstein S, Wang S. A comprehensive immunization strategy to eliminate transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) part 1: immunizations of infants, children, and adolescents. Atlanta: CDC; 2005. p. 1–23.

Wiseman E, Fraser MA, Holden S, Glass A, Kidson BL, Heron LG, et al. Perinatal transmission of hepatitis B virus: an Australian experience. Med J Aust. 2009;190(9):489.

Guo Z, Xiaohong S, Feng Y, Wang B, Feng L, Wang S, et al. Risk factors of HBV intrauterine transmission among HBsAg-positive pregnant women. J Viral Hepat. 2013;20:317–21.

Kang W, Ding Z, Shen L, Zhao Z, Huang G, Zhang J, et al. Risk factors associated with immunoprophylaxis failure against mother to child transmission of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis B vaccination status in Yunnan Province, China. Vaccine. 2014;32:3362–6.

Kubo A, Shlager L, Marks A, Lakritz D, Beaumont C, Gabellini K, et al. Prevention of vertical transmission of hepatitis B: an observational study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:828–35.

Chang MS, Gavini S, Andrade PC, McNabb-Baltar J. Caesarean section to prevent transmission of hepatitis B: a meta-analysis. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28:439–44.

Nguyen V, Tan PK, Greenup AJ, Glass A, Davison S, Samarsinghe D, et al. Anti-viral therapy for prevention of perinatal HBV transmission: extending therapy beyond birth does not protect against post-partum flare. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:1225–34. Observational study of 101 pregnancies in women with HBV treated with either lamivudine, tenofovir or no antiviral. Post partum flare rates between 30–50%, not significantly impacted by length of post-partum antiviral treatment, most of which were mild and resolved spontaneously.

Giles M, Visvanathan K, Lewin S, Bowden S, Locarnini S, Spelman T, et al. Clinical and virologic predictors of hepatic flares in pregnant women with chronic hepatitis B. Gut. 2014;1–6.

World Health Organization. First-line ART for pregnant and breastfeeding women and ARV drugs for their infants. June 2013. 9 March 2015 <www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/arv2013/art/artpregnantwomen/en>.

Ehrhardt S, Xie C, Guo N, Nelson K, Thio C. Breastfeeding while taking lamivudine or tenofovir disoproxil fumarate: a review of the evidence. CID. 2015;60:275–8. Narrative review of the evidence for antiviral use while breastfeeding.

Yeh RF, Rezk NL, Kashuba AD, et al. Genital tract, cord blood, and amniotic fluid exposures of seven antiretroviral drugs during and after pregnancy in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected women. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:2367–74.

Shapiro RL, Holland DT, Capparelli E, et al. Antiretroviral concentrations in breastfeeding infants of women in Botswana receiving antiretroviral treatment. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:720–7.

Giuliano M, Guidotti G, Andreotti M, et al. Triple antiretroviral prophylaxis administered during pregnancy and after delivery significantly reduces breast milk viral load: a study within the Drug Resource Enhancement Against AIDS and Malnutrition Program. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44:286–91.

Moodley J, Moodley D, Pillay K, et al. Pharmacokinetics and antiretroviral activity of lamivudine alone or when coadministered with zidovudine in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected pregnant women and their offspring. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1327–33.

Chappuy H, Treluyer JM, Jullien V, et al. Maternal-fetal transfer and amniotic fluid accumulation of nucleoside analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitors in human immunodeficiency virus-infected pregnant women. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:4332–6.

Mandelbrot L, Peytavin G, Firtion G, Farinotti R. Maternal-fetal transfer and amniotic fluid accumulation of lamivudine in human immunodeficiency virus-infected pregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:153–8.

Corbett AH, Kayira D, White NR, et al. Antiretroviral pharmacokinetics in mothers and breastfeeding infants from 6 to 24 weeks post partum: results of the BAN study. Antivir Ther. 2014. doi:10.3851/IMP2739.

Palombi L, Pirillo MF, Andreotti M, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for breastfeeding transmission in Malawi: drug concentrations, virological efficacy and safety. Antivir Ther. 2012;17:1511–9.

Mirochnick M, Thomas T, Capparelli E, et al. Antiretroviral concentrations in breastfeeding infants of mothers receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:1170–6.

Benaboud S, Pruvost A, Coffie PA, et al. Concentrations of tenofovir and emtricitabine in breast milk of HIV-1-infected women in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire, in the ANRS 12109 TEmAA study, step 2. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:1315–7.

Van Rompay KK, Brignolo LL, Meyer DJ, et al. Biological effects of short-term or prolonged administration of 9-[2-(phosphonomethoxy) propyl]adenine (tenofovir) to newborn and infant rhesus macaques. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:1469–87.

Chen X, Chen J, Wen J, Xu C, Zhang S, et al. Breastfeeding is not a risk factor for mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B virus. PLoS ONE. 2013;8, e55303. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0055303.

Chang M, Tuomala R, Rutherford A, Muthoka M, Andersson K, Burman B, et al. Postpartum care for mothers diagnosed with hepatitis B during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:1.e1–7.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

Erin Kelly declares no conflict of interest. Marion Peters reports honoraria from J&J, Biotron, Merck, Roche, and Genentech Research and Development.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Hepatitis B

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kelly, E., Peters, M.G. Management of HBV in Pregnancy. Curr Hepatology Rep 14, 145–152 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11901-015-0266-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11901-015-0266-6