Abstract

Demands for police reforms to address racial injustice and excessive force have increased since the release of a video showing George Floyd dying as a result of police brutality. A promising recommendation to reduce conflict and violent encounters between the police and the public that has the support of academics, expert panels on policing, and community leaders is police deescalation training. Currently, some law enforcement agencies require deescalation training for their offices and some do not. The training that is provided in deescalation varies in content, by style of instruction, and dosage. The lack of standardization is due, in part, to a lack published research on police deescalation. For this article, agency practices supportive of deescalation are reviewed. Communication techniques that officers use to defuse hostility, avoid physical aggression, and calm people in crisis to increase the likelihood of voluntary compliance are reviewed. Methods involving (a) agency surveys, (b) patrol officer surveys, (c) use of force and incident reports, (d) citizen complaints, (e) interviews, (f) focus groups, and (g) police ride alongs are examined for how they may be applied to the study of deescalation and use of force.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

With the release of a video of George Floyd dying as a result of police brutality (May 25, 2020) and the continued release of videos of police using excessive force, unresolved grievances concerning racial injustice have erupted into social unrest, protest, and calls for police reform. The global Black Lives Matter movement has grown in prominence; there has been an upsurge in white nationalist activity and provocation (Black Lives Matter: 2020 Impact Report, 2020; New Hate and Old: The Changing Face of American White Supremacy 2018), and an increase in hostility towards the police (Hutchinson 2020). Surveys indicate that confidence in the police has declined and that nonwhite Americans have less favorable views of the police than white Americans. For the first time in 27 years, a Gallop poll of US adults (n = 1226) found that the majority of the respondents, at 52%, do not have confidence in the police. This included 43% of the white respondents and 81% of the black respondents (Jones 2020). US adults (n = 875) were surveyed about their views on police brutality by Graham et al. (2020). About 32% of the black and 26% of the Hispanic respondents reported that they worry a lot about police brutality in comparison to only 6.6% of the white respondents. Less favorable views of the police among non-white Americans are likely a reflection of the increased likelihood that non-white Americans have of experiencing and witnessing police use force compared with white Americans.

Police use of Force

Lautenschlager and Omori (2018) studied police use of force across neighborhoods in New York City from 2003–2012 using data from the NYPD’s Stop, Question, and Frisk Database . It was discovered that the black neighborhoods experienced more frequent police actions involving lower levels of force (against the wall, pat-down, handcuff) and more severe levels of force (suspect on the ground, pepper-sprayed, baton strike, weapon-pointed) than the neighborhoods with greater ethnic and racial heterogeneity. In the more ethnically and racially diverse neighborhoods, the police used force relatively infrequently. But when force was used, it tended to be severe. Worall et al. (2020) examined the use of force actions of the Dallas Police Department (n = 2150) that occurred in 2017. The black suspects in these cases were found to be 2/3rds more likely to have had a gun or electric control device pointed at them by a police officer than the white suspects after controlling the for the risk level of the call; the gender, mental stability, drug use, and aggression level of the suspect; and the demographics of the officer.

These findings indicate that officers use force more frequently, at more mild and severe levels, when policing in black compared with more affluent neighborhoods. Police actions in more affluent neighborhoods are relatively infrequent. But when they occur, they tend to involve a severe level of force, suggesting that police are generally reluctant to use force in more affluent neighborhoods except for the most serious cases.

Less experienced, white and Hispanic, and male police officers have been found to use force more often than experienced, black, and female officers. Officers who participated in the national survey of police (n = 7917) for the Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) were asked if they physically struggled or fought with a suspect in the past month (Morin et al. 2017). About 22% of the female officers compared with 35% of the male officers reported that they physically struggled or fought with a suspect in the past month. By race and ethnicity, 20% of the black compared with 33% of the Hispanic and 36% of the white officers physically struggled or fought with a suspect in the past month. About 33% of the officers with more than 5 years of experience compared with 50% of the officers with less than 5 years of policing physically struggled or fought with a suspect. Ridgeway (2016) examined police shootings (n = 106) involving 291 officers that occurred in New York City from 2004 to 2006. The officers with more experience interacting with criminal suspects making misdemeanor arrests and the officers who were relatively older when hired were found to be less likelihood of being involved in a shooting compared with officers with less experience and the officers who were hired when they were younger.

Research that indicates that officers with more experience interacting with criminal suspects use force less often than officers with less experience interacting with criminal suspects (Morin et al. 2017; Ridgeway 2016) supports the policy that some sheriff departments have of requiring new deputies to work at the jail to gain experience interacting with criminal suspects and offenders before putting them out on patrol. The finding that female officers tend to be better at resolving conflicts without having to resort to force than male officers is one among many reasons why increased recruitment and promotion of female officers is beneficial (Lonsway, Moore, Harrington, and Spillar 2003; Morin et al. 2017). The finding that black officers were more likely to be involved in police shootings than white officers in New York City (Lautenschlager and Omori 2018) could be related to black officers being disproportionately assigned to neighborhoods where violent crimes and police use of force actions occur more often (Gray and Parker 2020; Helms and Costanza 2019; Lautenschlager and Omori 2018; Worall et al. 2020) and should be considered in the context that black officers report using force less often than white officers nationally (Morin et al. 2017) (Table 1 ).

According to the Washington Post’s Database of Fatal Force, approximately 1000 people are killed by the police per year. About 26% of the people who are killed by the police are black and 49% are white. Considering that about 13% of the general population is black and 62% is white, blacks are about 2.5 times more likely than whites to be killed by the police. The person was not armed with a firearm for about 40% of the fatalities and had signs of mental illness for about 10% of the fatalities (The Washington Post’s Database of Fatal Force, 2020). Data from the Mapping Police Violence Program and from the Killed by Police Database indicate that police killings of citizens occur most often in the US counties with income inequality, unemployment, and predominately black and Hispanic populations, and in the states with more conservative ideologies (Gray and Parker 2020; Helms and Costanza 2019). It has been estimated that about 10% of the cases involve individuals who committed “suicide by cop” ('Suicide by Cop’ Is a Persistent Problem. Here’s How to Prevent It, 2020).

Police deescalation training has been recommended to reduce conflict and violent interactions between the police and the public by academics, community leaders, and expert panels on policing for a variety of situations involving intoxicated, mentally ill, and suicidal people; domestic disputes; and victims of an accidents, assaults, and other circumstances (Final Report of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing 2015; Limiting Police Use of Force: Promising Community-Centered Strategies 2014; President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and the Administration of Justice 2020). It is supported by the majority of the American public (Schumaker 2020; Shannon 2020); and it is believed that if officers were adequately trained, encouraged, and supported in their deescalation efforts that there would be (a) fewer fatal encounters between the police and the public, (b) fewer injuries for officers and suspects, (c) greater flexibility in the use of misdemeanor charges, (d) fewer people with serious mental illnesses being sent to jail, (e) fewer law suits, (f) improved community relations, and (g) improved officer job satisfaction (Guiding Principles on Use of Force 2016; President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and the Administration of Justice 2020; Morin et al. 2017; Oliva et al. 2010; Vickers 2000).

Deescalation as a Central Theme of Policing

The Guiding Principles on Use of Force (2016) report explains that departments can establish deescalation as a central theme of their policing by emphasizing the sanctity of all human life and that officers use the minimal amount of force necessary to mitigate an incident, make an arrest, or protect themselves or others from harm in their value statements, policies, and training materials. When possible, officers should use advisements, warnings, and persuasion to convince individuals to comply with law enforcement objectives before resorting to using force. If officers witnesses a fellow officer using force or about to use force unnecessarily, they should be obligated to intervene. References to the 21-foot rule pertaining to individuals who are armed with an edged weapon should be removed from policy and training manuals. Instead, tactics such as (a) slowing down the situation if immediate action is not required, (b) proportionate use of force, (c) using distance and cover to create a reaction gap or safe zone, and (d) calling for supervision and back-up should be emphasized.

When responding to a call, it is recommended that officers follow the five-step critical decision-making model (CDM) (Morin et al. 2017). Officers who have been taught the CDM process (a) gather information on the way to a call, (b) determine whether immediate action is required in response to an imminent threat, (c) consider what the law requires, (d) decide on a plan of action, and (e) implement the plan and determine what else needs to be done. In support of the sanctity of all human life, departments should have agreements with local providers for referral procedures that officers may use when they encounter someone in need of services for (a) physical, mental health, and substance abuse issues; (b) a psychiatric hold; (c) shelter; (d) child welfare and abuse; (e) veterans; and (f) human trafficking (Limiting Police Use of Force: Promising Community-Centered Strategies 2014) (Table 2).

Law enforcement agencies should be documenting the use of force actions of their officers and verifying the written reports of these actions with body or dashboard camera footage (Morin et al. 2017). The trend has been moving in this direction. As of January of 2019, some 5043 out of 18,514 federal, state, local, and tribal law enforcement agencies reported the incidents involving their officers that resulted in the discharging of a firearm, a fatality, or serious bodily injury to the Bureau of Justice Statistics for the National Use-of-Force database, representing 41% of sworn officers in the USA (National Use of Force Database, n.d.; Use of Force Report for 2019: Law Enforcement Collections 2020).

In the interest of transparency and the public’s trust in the police, departments should be producing annual reports of their officer-involved shootings, deployments of less-lethal devices, and use of canines (Final Report of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing 2015). Information should be provided about the circumstances of the event, the demographics of the officer(s) and subject(s) involved, and the department’s efforts to reduce bias and prevent discrimination. These reports should be publicly available and featured on the department’s website, see the Palm Beach County Sheriff’s Office for example (Internal Affairs Annual Report: The Palm Beach County Sheriff’s Office 2019).

Agencies should be following recommended critical incident response procedures for officer-involved shootings and other serious incidents that have the potential of damaging community relations. Beyond the criminal investigation of such incidents, departments should be prepared with (a) a list of key community leaders to contact, (b) a media plan, (c) an advisory board that reflects the diversity of the community to review cases and suggest changes in policy or procedure if appropriate, and (d) a plan to initiate follow-up that involves the community (Finn 2001; Police Critical Incident Checklist, n.d.).

Training in Verbal Deescalation

The Dolan Consulting Group is an academy that provides training for law enforcement officers and other public service professionals on a variety of topics including a course titled Verbal De-Escalation & Surviving Verbal Abuse. The objectives of this course are (a) to teach verbal and non-verbal communication techniques most likely to defuse hostility, avoid physical aggression, and obtain voluntary compliance; (b) to protect public service professionals from saying or doing something that unnecessarily jeopardizes safety or that puts their career at risk, and (c) to save money and resources by limiting the number of times that officers must call assistance for a physical intervention. It is made clear that verbal deescalation tactics are not appropriate or useful for all situations like when someone is threatening people with a firearm and action must be taken immediately. But for most of the interactions that officers have with the public, verbal deescalation techniques are useful (Dolan 2020; Dolan and Johnson 2020).

Instruction Provided

The Verbal De-Escalation & Surviving Verbal Abuse course is taught using a three-step instructional process of explanation, demonstration, and practical application. For the first step, students learn approximately thirty verbal deescalation concepts and techniques via basic classroom instruction (see Table 3). Each concept is explained using real life stories and video clips of officers responding to situations. Examples of situations that were handled poorly and of situations that were managed in an exemplary manner are provided for students to examine, discuss, and contrast. For the second step, students are placed into groups of two to practice the verbal deescalation skills of making meet and greet statements, verbally deflecting abuse, and providing a closing. After becoming comfortable with these skills, role-playing scenarios are used to practice responding to challenging and manipulating people whose aim it is to provoke the officer into doing or saying something unprofessional (Dolan and Johnson 2020, Johnson 2016).

Making an Introduction

If safety permits, officers are taught to begin interactions with the public by (a) making a friendly introduction, (b) identifying the department that they represent, and (c) explaining the reason for the interaction with statements like… “Hello, my name is officer ______, with the ______ police or sheriff department. The reason that I stopped you/We need to talk to you/Why I am here/etc. is ______”. When more than one officer is on the scene, the one-voice rule applies. The one-voice rule is that only one officer should communicate with suspects and others present during an encounter to avoid the confusion that could occur if more than one officer is speaking (Dolan 2018).

Ethos, Logos, and Pathos

Officers are introduced to Dolan’s Rhetorical Continuum of Persuasion. This continuum applies Aristotle’s concepts of ethos, logos, and pathos to police interactions with the public (Dolan 2017b, 2018). For the training, ethos refers to the persuasive power of an officer’s appearance, words, and actions. Officers who display a professional ethos are more likely to gain compliance because they are more likely to be viewed as legitimate and competent. Logos is an officer’s ability to persuade others to comply by explaining the logic and reasonableness of their request. It addresses the human universal that people want to be told why when they are asked to do something.

Some of the people that officers interact with will provide excuses for why they should not have to comply with their request. Officers are advised to respond to individuals who provide excuses for their non-compliance by briefly restating the excuse back to the person. If it is not valid, the officer should immediately follow up with an adverb like “however” and contrast the excuse with the legitimate reason for why the person needs to comply. Providing the reason “why” when asking someone to do something is referred to as commander’s intent. Suggested phrases for officers when responding to people who provide excuses include… “I can see you are upset and I agree it’s difficult, however ___” and “I hear what you’re saying, that ____ however____”.

Pathos is persuasion by appealing to a person’s self-interest. Some of the people that officers encounter will continue to verbally resist even after a legitimate reason for the officer’s request has been explained to them. Officers should inform such individuals about how complying with their request will benefit them personally by, perhaps, explaining the negative consequences for refusing to comply. If an individual continues to resist after having the negative consequences of non-cooperation explained, the officer should ask the person to confirm that he or she really wants the consequences before escalating to physical action. A suggested phrase that an officer may use is “Sir, so what you’re saying is you would rather we use force to take you to jail and risk you getting hurt in the process. Is that what you are really saying? I need to know if that is really what you want.”

Agreeable, Challenging, and Manipulative People

It is explained that the people who officers interact with be either agreeable, challenging, or manipulative (Dolan 2017a, b, Dolan and Johnson 2017). Agreeable people are those who willingly comply with an officer’s requests. Challenging people will question the legitimacy of an officer’s request and attempt to debate. Some people will say things with the intent of making the officer angry. A manipulating person may say things with the aim of provoking an officer into saying or doing something unprofessional that may jeopardize his or her career.

The term “rope-a-doped” is used to refer to when an officer says or does something unprofessional as a result of being provoked by a member of the public (Table 4 ). To avoid being rope-a-doped, officers are instructed to respond to insults by (a) briefly restating it and (b) immediately following up with an adverb like however (c) to redirect the conversation back to the matter at hand and explain the options that the person has available for compliance. Suggested phrases to deflect verbal abuse include “I hear what you’re saying, you think I’m a racist, however my reason for stopping you today” and “I hear what you’re saying. You’re angry we weren’t here quicker, but we’re here now. What can we do to help you now?”. Officers are advised to conclude their interactions with members of the public by informing them of their concern for their well-being. Suggested phrases for closing an interaction include “Your safety is important to me, be careful as you ____.” or “For your safety and mine, ____”.

Officers are taught Dolan’s Contact and Cover Principle, which is to be on the lookout and intervene if they notice a fellow officer in danger of being rope-a-doped (Dolan 2016, Dolan 2017b). If an officer notices a fellow officer involved in a verbal altercation with a member of the public, the officer is to intervene by taking control of the interaction and directing the officer involved in the altercation away from the person. It is recommended that departments establish a warning phrase to use for such situations, such as “Sergeant Coffee wants you to call him right away. I will talk to this person while you take care of that.” If an officer catches him or herself falling victim to being rope-a-doped, the officer should stop the conversation by using his or her hands to make a time-out signal and then restart the conversation with a statement like, “Whoa, that didn’t come out right. Can I start over?”.

Body Language Cues of Impending Violence

Some people will respond violently or attempt to flee to avoid complying with an officer’s request (Dolan 2018). Particularly dangerous are people who are manipulative and violent, as they may feign compliance in an attempt to lure the officer into a false sense of security while looking for an opportunity to strike. Officers are taught to be attentive to potential violent responses from people by paying attention to their body language. During the training, video examples are used to identify and discuss body language indicators of impending violence. Johnson and Aaron (2013) investigated non-verbal behavior indicators of violence by presenting a verbal argument scenario to a sample of 178 university students with a list of non-verbal behaviors that their opponent could display. The students were asked to rank each of the behaviors by the level of concern that it would raise for them about their opponent becoming violent. The results of the non-verbal behaviors ranked from the most to least indicative of impending violence are listed in the table below (Table 5 ).

In addition to agreeable, challenging, and manipulative people (Dolan 2017a, b, Dolan and Johnson 2017), officers also interact with people who are in crisis. A person in crisis is someone who is acting strangely, disorderly, illegally, or dangerously due to being out of control emotionally (Fitch 2016; Oliva et al. 2010; Todak 2017). This could be due to issues such as (a) suicidal despair, (b) trauma caused by being a victim of a crime or accident, (c) a mental illness or disorder, (d) addiction withdrawal, or (e) an interruption in medication. Verbal deescalation techniques recommended for people in crisis focus on calming the person, showing respect, and gaining their trust to increase their likelihood of compliance.

Verbal Deescalation for People in Crisis

The verbal deescalation techniques of (a) modeling and making an introduction, (b) using “I” statements, (c) asking questions, and (d) paraphrasing have been recommended for interacting with a person in crisis (Fitch 2016; Limiting Police Use of Force: Promising Community-Centered Strategies 2014; Oliva et al. 2010; Todak 2017). For modeling, an officer needs to be aware of his or her body posture, demeanor, and tone of voice. As the officer approaches a person in crisis, the officer should model the type of behavior that he or she would like the person to adopt by demonstrating a relaxed demeanor and calm voice. While doing so, the officer should make a non-threatening introduction by saying something like “Hello, my name is ______, I was called out to see how we can help”, followed by a question like “What is your name?”.

Officers learn to avoid making “you” statements like “you need to listen” or “you are not explaining yourself very well” because they may come across as accusatory and judgmental. Instead, officers develop the habit of using “I” statements like “I need to better explain myself,” “I don’t understand,” or “I would like your help in better understanding what’s going on.” A large part of the deescalation process involves asking questions and listening to a person’s concerns. Officers ask questions to learn about the circumstances that precipitated the crisis, to learn about the person’s problem, and to calm the person. What is learned informs their decisions about how to respond and whether additional personnel and resources may be needed.

Asking Questions

Questions require people to engage in non-emotional rational thinking to formulate and provide a response, especially open-ended questions. As a person who is in a heightened state of emotion responds to an officer’s questions, the regions of the person’s brain associated with rational thinking, the prefrontal cortex, become more active. This shifts the person’s perspective from being based on emotions to being more rational. By asking questions, listening, and engaging in dialog with a person in crisis, the officer is helping the person gain control over their emotions. It has the effect of making the person more reasonable, calm, and less likely to react emotionally. Open-ended questions like “can you help me understand what happened?” and encouragers like “tell me more,” and “can you give me an example?” are useful for obtaining information and creating dialog, while yes or no close-ended questions may be useful when an officer is seeking to reach an agreement.

Paraphrasing is listening to a person explain his or her problem or concerns and then restating what you heard back to the person. People who are in crisis often feel as though nobody is listening. They have a need to be heard and will repeat the same message multiple times in hope of finally getting through to someone who cares. Restating the problems of individuals who are in crisis back to them acknowledges this need by letting the person know that he or she has, indeed, been heard. Paraphrasing facilitates communication because it gives people an opportunity to provide additional details and correct misunderstandings.

These techniques support the procedural justice ideals of transparency, treating all people with dignity and respect, and giving people an opportunity to be heard. They help officers calm and build rapport with individuals in crisis so they will be more reasonable and likely to be persuaded to voluntarily comply with what the officer needs them to do in support of the principle of the least amount of force necessary. The goal is that the officer will not have to use any force (Fitch 2016; Limiting Police Use of Force: Promising Community-Centered Strategies 2014; Oliva et al. 2010; Todak 2017).

Using Empathy to Promote Compliance

Todak (2017) interviewed officers from the Spokane, WA, police department who were nominated by their peers as being highly skilled in conflict-deescalation. The officers explained that they treat everyone with respect. When they encounter someone in crisis, they attempt to understand their point of view by imagining themselves in the person’s situation. They explain the law pertaining to the situation to the person, what this means in regard to what the officer needs the person to do, and how they will help the person if he or she complies. If it does not jeopardize safety or violate the law, they will reward positive steps towards compliance, such as giving a person in crisis a cigarette for agreeing to sit down and listen. The officers cautioned that it is more difficult to obtain compliance from people who are drunk, under the influence of drugs, or mentally ill due to their diminished ability to think rationally. Sometimes, crisis situations involve a committed person who has made up their mind prior to the officer arriving on the scene to fight the police, jump off a bridge, or provoke a cop to shoot and will not be persuaded otherwise by deescalation tactics.

Fitch (2016) recommends that officers follow the three-step describe, express, and request (DER) script to encourage compliance from people in crisis. Officers who use the DER script promote compliance by describing the person’s behavior, expressing or explaining how the person’s behavior is making the situation more difficult, and making a specific request to the person to change the behavior (Table 6 ).

Deescalation Training is not Standardized

The officers who participated in national survey of police (n = 7917) for PERF were asked if they have received at least 4 h of training in deescalation (Morin et al. 2017). The majority of the officers, at 66%, reported that they have not. A similar percentage, at 64%, reported that they have not received at least 4 h of training in crisis intervention. Noteworthy is that 61% of the black officers, 44% of the Hispanic officers, and 37% of the white officers reported that they worry that some of their colleagues do not spend enough time diagnosing a situation before deciding to act decisively, i.e., use force. Also, 15% of the officers felt that they should not be required to intervene when a fellow officer is not following the department use of force guidelines.

Gilbert (2017) reports that police officers are not required to receive training in deescalation in 34 states, and the majority of agencies only a provide a minimal amount or no training in deescalation for their officers due to beliefs that the training is too expensive, that it is not needed, and that it may jeopardize officer safety. The training that officers do receive in deescalation varies in content, by style of instruction, and dosage. There is a lack of standardization. This is due, in part, to a lack published research on police deescalation. Engel et al. (2020) reviewed the literature for studies on police deescalation over a 40-year period and did not find any. The training that officers receive in deescalation is an extension of the training that they receive in use of force. In the next section, (a) agency surveys, (b) patrol officer surveys, (c) use of force and incident reports, (d) citizen complaints, (e) interviews, (f) focus groups, and (g) police ride alongs are discussed for how they may be applied to the study of deescalation and use of force.

Identifying Agency Use of Force and Deescalation Policies

Terrill et al. (2012) surveyed agencies to identify the type of use of force polices that they follow and their reporting mechanisms. Surveys were mailed to a sample of police departments (n = 1083) across the country stratified by agency size (i.e., the number of sworn officers) and type (i.e., municipal or sheriff) to determine the type of use of force polices and report mechanisms that agencies use. A total of 662 responded. The police agencies were asked (a) if they had a written policy on less than lethal force, (b) if they follow a use a force continuum, (e) about how they file their use of force reports, and (f) about the number of sworn and unsworn officers, calls for service, and crimes reported to the agency over a 2-year period (see National Survey of Police Agencies: Examining Force Types: Appendix A).

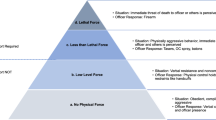

The use of force polices that agencies follow varied significantly, ranging from being restrictive by only allowing officers to use more severe forms of force on individuals who are actively aggressive to more lenient by allowing officers to use nearly all types of force against nearly all types of citizen resistance, short of extreme imbalances like using a baton in response to suspect complaint. About 80% of the agencies reported that they followed a use of force continuum for their policy. Approximately 73% of the use of force continuums used were linear, 10% were a matrix/box design, and 10% were circular in design.

A similar survey could be used to identify and gain insights into the deescalation policies that agencies follow. The information obtained could be used to rate agencies by their level of support for deescalation and to identify agencies to approach for site visits and deeper analysis. Topics for a survey of police agencies about deescalation are listed in the table below (Table 7).

Police Agency Site Visits

Terrill et al. (2012) secured agreements with the police administrators of eight of the agencies that they surveyed to conduct site visits and collect data over a 2-year period (Columbus, OH; Charlotte Mecklenburg, NC; Portland, OR; Albuquerque, NM; Colorado Springs, CO; St. Petersburg, FL; Fort Wayne, IN; and Knoxville, TN). These agencies were selected because they (a) engaged in regular filing of use of force reports, (b) had a consistent use of force policy and reporting procedure, (c) were a mid-to-large size agency, and (d) were comparable in respect to jurisdictional size, crime rate, workload, and socioeconomic status (see Table 8). During the site visits, researchers (a) administered surveys to patrol officers on their views about their use of force policy; (b) obtained 2 years of records on the agencies’ use of force encounters, citizen complaints, reported crimes, arrests, and calls for service; (c) reviewed the agencies’ organizational charts, rosters, rules, and regulation manuals; and (d) informally interviewed officials at the middle and upper management levels.

Surveying Patrol Officers

Terrill et al. (2012) surveyed the patrol officers of the agencies they visited about (a) whether their less than lethal policy assists them in their decision-making is too restrictive and is clear about when force can and can not be used, (b) whether they agree with their less than lethal policy, and (c) the impact of their less than lethal policy on suspect injuries, officer injuries, citizen complaints, and lawsuits (see National Survey of Police Agencies: Examining Force Types: Appendix C). Prior to administering surveys, the names and work schedules of the officers who were to be surveyed were obtained from “master rolls” provided by the agencies. This allowed the researchers to plan out when to visit an agency’s different precincts, districts, and shifts during roll call to administer surveys to the patrol officers. Each officer’s name was printed on an informed consent form along with a random number. The number on the informed consent form was also printed on survey that was stapled to the informed consent form. No names were written or printed on the surveys. The numbers were used to keep track of which officers had been surveyed and to link the survey responses to the agency’s use of force reports and citizen complaint files. Shift commanders were notified with the dates and times of when they would be administrating surveys so that they would not be caught off guard. The purpose of the survey, the informed consent, and confidentiality and anonymity were explained to the officers before they were asked to fill out the survey. They were informed that their agency was selected because the study was examining how the use of force policies that departments use vary. They were not selected because of something that the department or individuals within the department failed to do or did incorrectly. It took between 7 to 10 days to survey the patrol officers of each of the precincts, districts, and shifts of an agency. The completion rate for the survey was approximately 96.5%.

A survey and procedure similar to that used by Terrill et al. (2012) to interview patrol officers about their use of force polices could be used to survey patrol officers about deescalation. Topics about use of force and deescalation to include on a survey of patrol officers are listed in the table below (Table 9 ) (Dolan and Johnson 2020; Guiding Principles on Use of Force 2016; Morin et al. 2017; Terrill et al. 2012).

Use of Force Reports

Terrill et al. (2012) obtained information from examining the use of force reports of the agencies they visited about (a) the number of use of force encounters that occurred and (b) the type of force used, (c) the level of citizen resistance, (d) whether the suspect had a weapon, (e) whether the suspect or officer suffered an injury, (f) whether the suspect had signs of substance abuse or mental illness, and (g) the demographics of the suspect during the use of force encounters. Some of the agencies catalogued their use of force records electronically, some kept paper records, and the others used a combination of electronic data and paper records. The type of force used by the officer that was indicated on the reports was classified into the categories of weaponless tactics (handcuffing, firm grip, pressure points, control maneuvers, takedowns, and empty hand strikes) and weapon tactics (chemical sprays, baton, CED, impact munitions, and firearm). The level of citizen resistance indicated on the use for force reports was classified into the categories of (a) compliance and (b) passive, (c) verbal, (d) defensive, (e) active, and (f) deadly resistance (The Use-of-Force Continuum 2009) (Table 10 ).

The uses of force policies of six of the eight agencies that were studied were ranked by their level of restrictiveness. This was done by comparing the level of force that a policy permits in relation to the level of citizen resistance. Colorado Springs was the agency that had the most restrictive use of force policy. Albuquerque had the least restrictive policy (see Table 11). Two of the agencies, Fort Wayne and Knoxville, were not compared because their use of force polices did not connect the types of force that officers may use to levels of citizen resistance.

Multivariate analyses were used to examine the relationship between the levels of force that officers used in response to the level of “citizen resistance” while controlling for the officer’s agency and for the sex, race, age, drug use, and mental impairment of the suspect. The level of force that officers used, the dependent variable, was grouped into four categories ranging from (0) soft hands to (3) deadly force. The agencies were included in the analyses as dummy variables. Albuquerque was used as the reference agency because it is was the agency that had the least restrictive use of force policy (Table 12 ).

Suspect and Officer Injuries

Seven out of eight of the agencies that Terrill et al. (2012) visited indicated if a suspect was injured on their use of force reports. The percentage of use of force encounters that result in an injury for the suspect varied greatly between agencies, ranging from 15.9% for St. Petersburg to 73.5% for Charlotte-Mecklenburg. The high percentage of use of force encounters that resulted in an injury for the suspect for Charlotte-Mecklenburg makes it an outlier in comparison with the other agencies. Officers were less likely to suffer an injury during a use of force encounter than the suspects. Six of the agencies indicated whether the officer suffered an injury. The percentage of use of force encounters that result in an injury for the officer varied from 8.1% for Columbus to 13.4% for Charlotte (Table 13 ).

If an injury occurred during a use of force encounter, officers circled the type from a list of five categories of injuries on their use of force reports for some of the agencies and wrote in the injuries that occurred in a blank box for the other agencies. The injuries that were indicated on the use of force reports were coded into the categories of (a) bruises, (b) abrasions, (c) lacerations, (d) broken bones, and (e) something else. The most common were abrasions, lacerations, and something else for both suspects and officers (Table 14 ).

Deescalation Incident Reports

Agencies could be encouraged to have their officers complete “deescalation incident” reports similar to their use of force reports after responding to situations without having to use force that had a potential for violence or that involved a person in crisis (The President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing Implementation Guide: Moving Recommendations to Action 2015). Officers could report the reason for the call, the number of people involved in the encounter, and whether the primary person who they interacted with was a challenging or manipulative person (Dolan 2020; Dolan and Johnson 2020) or a person in crisis (Fitch 2016; Oliva et al. 2010; Todak 2017). They could indicate how they deescalated the situation and whether it was resolved with a warning, referral, arrest, or commitment. Information could be provided on the person’s demographics, history of prior contacts, and whether there were signs of substance abuse or mental illness. The table below provides a list of topics that officers could be asked to include on a deescalation incident report (Table 15 ).

Departments that develop measures to track their deescalation efforts could evaluate them in the context of the more traditional measures of police performance used for COMPSTAT (President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing Implementation Guide: Moving Recommendations to Action 2015). The information generated would provide departments with the ability to (a) evaluate their deescalation efforts, (b) recognize their officers for implementing deescalation techniques, (c) produce reports on their use of force and deescalation efforts, and (d) justify changes. Some departments currently keep track of events like their firearm discharges, use-of-force incidents, and citizen complaints using an electronic database with an early warning system that alerts a supervisor if an officer exceeds a certain threshold of significant events indicating that an intervention like counseling or training may be appropriate to address potential problems before they escalate (Limiting Police Use of Force: Promising Community-Centered Strategies 2014).

Examining Citizen Complaints

As the quality of the deescalation training improves, becomes more institutionalized, and the proportion of officers who are trained increases, there should be a decrease in conflict and the likelihood of violent encounters between the police and the public. One indicator of the relationship between a police department and the community are the complaints that citizens file against an agency. Terrill et al. (2012) examined the citizen complaints that were filed against the agencies they visited concerning an officer’s use of force and an officer’s discourteous behavior. Complaints were obtained from an internal affairs department for some of the agencies, from internal affairs and the officer’s chain of command for some of the agencies, and from a combination of department entities and external oversight agencies for the other agencies.

The number of complaints that the agencies received was compared with the number of (a) calls for service, (b) reported UCR Part 1 crimes, (c) arrests for UCR Part 1 crimes, and (d) use of force reports filed for the agencies over a 2-year period. The number of complaints that was filed varied against the agencies varied dramatically. Colorado Springs received one use for force complaint for every 2803 of their calls for service, 46 of their arrests, and 4 use of force encounters. For comparison, St. Petersburg only received a use of force complaint for every 17,885 of their calls for service, 314 of their arrests, and 95 use of force encounters (Table 16 ).

The outcomes of the citizen complaints were coded as (a) sustained, misconduct occurred; (b) not sustained, misconduct could not be proven or disproven; (c) exonerated, conduct was proper; or (d) unfounded, allegation was false. The percentage of the use of force complaints that were, sustained, found to have occurred varied from 0.0% for Fort Wayne and St. Petersburg to 5.0% for Albuquerque. The percentage of the discourteous behavior complaints that were sustained varied from 2.0% for Portland to 28% for Knoxville (Table 17 ).

Multivariate analyses were used to examine the agencies’ relative likelihood of receiving a citizen complaint after controlling for the sex, age, and race characteristics of the suspects. Albuquerque and St. Petersburg were the agencies that were the least likely to receive a citizen complaint. The finding that Albuquerque was less likely to receive a complaint filed against them than the other agencies is contrary to what would have been predicted because it is the agency with the most permissive use of force policy. Fort Wayne was the agency that was the most likely to receive a complaint (Table 18 ). The characteristics of the suspects did not have a statistically effect.

Interviews and Focus Groups with Officers Skilled in Deescalation

Todak (2017) asked the officers of the Spokane Police Department to nominate which of their fellow officers they believed were the best at deescalating difficult, potentially violent citizen encounters. The eight officers who received the most nominations were interviewed in a semi-structured format about their police experience, perceptions on deescalation, and insights from the field (see Table 19). The information gained from these interviews provided material to explore during the focus group sessions.

The focus group sessions began with a discussion on deescalation. Then, the group watched a body camera video of an officer’s encounter with a citizen that was successfully deescalated or that possibly could have been deescalated without having to resort to using force. A total of six videos were shown. Three of the videos were provided from the officers, and three of the videos were selected from the department’s body camera video storage system. Two of the videos depicted situations when deescalation tactics were not used or were used unsuccessfully. The other four videos were of situations when the officer was able to obtain compliance from the citizen without having to use force. After the video, the group discussed the nature of the call, the tactics that the officer(s) used, and whether the tactics were effective. Analysis of the focus group session transcripts revealed that the officers used the deescalation tactics of (a) displayed humanity, (b) listened, (c) honesty, (d) compromised, and (e) empowered. These and the tactics of (a) make an introduction, (b) used one voice, (c) deflected verbal abuse, (d) paraphrased, and (f) provided a closing (Dolan and Johnson 2020; Fitch 2016; Oliva et al. 2010) are described in the table below (Table 20 ).

Police Ride Alongs

Todak (2017) observed deescalation practices during citizen encounters while participating in police ride alongs. She completed 13 ride alongs with officers from the group of eight who were nominated as highly skilled in deescalation and 22 ride alongs with other officers. During these ride alongs, she observed 132 police-citizen interactions. A police-citizen interaction was considered any interaction that generated an official police response or that involved an officer in contact with a citizen for more than two minutes.

A verbal consent form was read to the officer at the beginning of each ride along, and information was recorded about the officer’s demographics, experience, and fatigue. As the officer responded to calls and interacted with citizens, information was recorded on the urgency of the call, whether the interaction was self-initiated, and whether there was an “anticipation of potential violence.” Anticipation of potential violence was measured by recording if the call indicated that violence was in progress or being threatened, if the person had history of violence, or if the officer felt the situation may become violent. Information about the citizen was recorded on (a) their demographics, (b) whether there were signs of substance abuse or mental illness, (c) whether the citizen disobeyed the officer or vocalized anti-police attitudes, and (d) whether the citizen was calm or agitated at the end of the encounter. When multiple citizens were present, information was recorded on the one citizen who could best be labeled as the suspect, who appeared to be the most escalated in behavior, or with whom the officer had the longest interaction. The officer’s body camera video footage of the encounter was reviewed for clarity following an interaction if needed.

Multivariate analyses were used to examine the influence of the officer, citizen, and situational characteristics on the likelihood that a deescalation technique was used and on the likelihood that it was successfully. Only a few variables were found to be associated with whether an officer used a deescalation tactic. Officers were more likely to use a deescalation tactic when they developed a plan of entry before making contact with the citizen. This may be because when an officer takes the time to develop a plan, they are more likely to be prepared to take specific tactical actions, like use a deescalation tactic. Attempts at deescalation were less likely to be successful when the interaction involved a citizen who disobeyed police orders, a citizen who made anti-police statements, a domestic violence call, and when the officer initiated the interaction. The officers were inconsistent in using deescalation when faced with particular problems, most likely because the officers for the department studied did not receive training in deescalation.

The deescalation tactic of humanity, i.e., talking to the person with respect, was the only tactic that was positively associated with a successful outcome; the person was not agitated or in crisis at the end of the interaction. The tactic of humanity may have been positive associated with successful deescalation outcomes while the other tactics were not because it is the simplest option for officers to go to when they are faced with a potential conflict. The tactics of honesty, listening, and empowerment may be second choice options that are used for more difficult situations when the tactic of humanity was unsuccessful (Table 21 ).

References

2019 Internal Affairs Annual Report: The Palm Beach County Sheriff’s Office (p. 48) (2019) Palm Beach County Sheriff’s Office Internal Affairs https://www.pbso.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/PBSO-ANNUAL-REPORT-2019web.pdf

Black Lives Matter: 2020 Impact Report (p. 42). (2020). Black Lives Matter. https://blacklivesmatter.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/blm-2020-impact-report.pdf

Dolan H (2016) Don’t get “rope-a-doped” (Chiefs Corner, p. 3). Dolan Consulting Group, LLC

Dolan H (2017a) Don’t lose the agreeable people! (Chiefs Corner, p. 4). Dolan Consulting Group, LLC

Dolan, H. and Johnson, R. (2017). The “Language of the Street” Fallacy (Chiefs Corner, p. 4). Dolan Consulting Group, LLC.

Dolan H (2017b) Verbal contact and cover: protecting your colleagues and your profession (Chiefs Corner, p. 3). Dolan Consulting Group, LLC

Dolan H (2018). Verbal de-escalation techniques: how they actually work (Chiefs Corner, p. 5). Dolan Consulting Group, LLC.

Dolan H (2020) What does verbal de-escalation training really mean. Dolan Consulting Group. https://www.dolanconsultinggroup.com/news/what-does-verbal-de-escalation-training-actually-mean/

Dolan H, Johnson R (2020) Surviving verbal conflict: verbal de-escalation techniques for law enforcement professionals instructor lesson plan: one day program (p. 53). Dolan Consulting Group, LLC

Engel R, McManus H, Herold T (2020) Does de-escalation training work?: a systematic review and call for evidence in police use-of-force reform. Criminol Public Policy. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12467

Final Report of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing (p. 115) (2015) Washington, DC: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services. https://de-escalate.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/The-Presidents-Task-Force-on-21st-Century-Policing.pdf

Finn P (2001) Citizen review of police: approaches and implementation (p. 181). U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/184430.pdf

Fitch BD (2016) Law enforcement, interpersonal communication, and conflict management: The Impact Model. Sage

Gilbert C (2017) Not trained to not kill: most states neglect ordering police to de-escalation tactics to avoid shootings. APM Reports Illuminating Journalism from American Public Media. https://www.apmreports.org/story/2017/05/05/police-de-escalation-training

Graham A, Haner M, Sloan M, Cullen F, Kulig T, Jonson CL (2020) Race and worrying about police brutality: the hidden injuries of minority status in America. Vic Offender 15(5):549–573

Gray A, Parker K (2020) Race and police killings: examining the links between racial threat and police shootings of Black Americans. Journal of Ethnicity in Criminal Justice, 27

Guiding Principles on Use of Force (No. 978–1–934485–33–0; Critical issues in policing series, p. 136) (2016) Police Executive Research Forum. https://www.policeforum.org/assets/guidingprinciples1.pdf

Helms R, Costanza SE (2019) Contextualizing race: a conceptual and empirical study of fatal interactions with police across US Counties J Ethn Crim Justice 30 https://doi.org/10.1080/15377938.2019.1692748

Hutchinson B (2020) Police officers killed surge 28% this year and some point to civil unrest and those looking to exploit it. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/US/police-officers-killed-surge-28-year-point-civil/story?id=71773405

Jones JM (2020) Black, White adults’ confidence diverges most on police (Social & Policy Issues). Gallop. https://news.gallup.com/poll/317114/black-white-adults-confidence-diverges-police.aspx

Johnson R, Aaron J (2013) Adult’s beliefs regarding nonviolent cues predictive of violence. Crim Justice Behav 40(8):881–894. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854813475347

Johnson, R. (2016). Surviving Verbal Conflict Train the Trainer: Adult Learning Principles (p. 10). Dolan Consulting Group, LLC.

Lautenschlager R, Omori M (2018) Racial threat, social (dis)organization, and the ecology of police: towards a macrolevel understanding of police use-of-force in communities of color. Justice Quarterly, 36(6). https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2018.1480792

Limiting police use of force: promising community-centered strategies (p. 26) (2014) PolicyLink Advancement Project.

Lonsway, K., Moore, M., Harrington, P., & Spillar, K. (2003). Hiring & Retaining More Women: The Advantages to Law Enforcement Agencies (p. 16). National Center for Women & Policing. A Division of the Feminist Majority Foundation.

Morin R, Parker K, Mercer A (2017) Behind the badge amid protests and calls for reform, how police view their jobs, key issues and recent fatal encounters between Blacks and police (p. 97). Pew Research Center. https://assets.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2017/01/06171402/Police-Report_FINAL_web.pdf

National use of force database. (n.d.) (2020) Retrieved September 21, 2020, from https://crime-data-explorer.fr.cloud.gov/officers/national/united-states/uof

New hate and old: the changing face of American White Supremacy (A Report from the Center on Extremism, p. 72) (2018) Anti-Defamation League. https://www.adl.org/media/11894/download

Oliva JR, Morgan R, Compton MT (2010) A practical overview of de-escalation skills in law enforcement: helping Individuals in crisis while reducing police liability and injury. Journal of Police Crisis Negotiations 10:15–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533258100378542

Police critical incident checklist (community relations services toolkit for policing). (n.d.) (2020) Retrieved September 8, 2020, from https://www.justice.gov/crs/file/836421/download

President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and the Administration of Justice, 6387592 (2020). https://www.justice.gov/ag/page/file/1289841/download

Ridgeway G (2016) Officer risk factors associated with police shootings: a matched case-control study. Statistics and Public Policy 3(1):6

Schumaker E (2020, July 5) Police reformers push for de-escalation training, but the jury is out on its effectiveness: some say the program makes good cops better and doesn’t reach bad cops. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/Health/police-reformers-push-de-escalation-training-jury-effectiveness/story?id=71262003

Shannon J (2020, June 29). USA TODAY poll: Americans want major police reform, more focus on serious crime. USA TODAY. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2020/06/29/us-police-reform-poll-finds-support-more-training-transparency/3259628001/

“Suicide by cop” is a persistent problem. Here’s how to prevent it. (2020). The Washington Post

Terrill W, Eugene P, Ingram J (2012) Final technical report draft: assessing police use of force policy and outcomes (No. 237794; p. 287). National Institute of Justice. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/237794.pdf

The President’s task force on 21st century policing implementation guide: moving recommendations to action (p. 38) (2015) COPS Office. https://policingequity.org/images/pdfs-doc/reports/TaskForce_FinalReport_ImplementationGuide.pdf

The use-of-force continuum (2009) National Institute of Justice. nij.ojp.gov: https://nij.ojp.gov/topics/articles/use-force-continuum

The Washington Post’s database of fatal force (Democracy Dies in Darkness) (2020) Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/investigations/police-shootings-database/

Todak N (2017) De-escalation in police-citizen encounters: a mixed methods study of a misunderstood policing strategy. Arizona State University.

Use of Force Report for 2019: Law Enforcement Collections (2020) Federal Bureau of Investigation Crime Data Explorer. https://crime-data-explorer.fr.cloud.gov/officers/national/united-states/uof

Vickers B (2000) Memphis, Tennessee, Police Department’s Crisis Intervention Team (NCJ 182501). U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/bja/182501.pdf

Worall J, Bishopp SA, Terrill W (2020) The effect of suspect race on police officers’ decisions to draw their weapons. Justice Quarterly, 21

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the author.

Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the author.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pontzer, D. Recommendations for Examining Police Deescalation and use of Force Training, Policies, and Outcomes. J Police Crim Psych 36, 314–332 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-021-09442-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-021-09442-1