Abstract

The relationship between perceived organizational support and its work-outcomes were usually based on social exchange theories. By keeping the social exchange framework in mind, this study additionally draws on “affective infusion model” and on “functionalist perspective” to study moderating role of cognitive emotion regulation (CER) in relationships among perceived organizational-supervisory family support (POFS–PSFS) and organizational identification, psychological contract breach, and work–family conflict (WFC). Results show that perceived POFS and PSFS are positively related to organizational identification, negatively related to WFC, and psychological contract breach. Employees with higher levels of CER tend to identify themselves more with their organizations and less with WFC (at Time 2) than do employees with low levels of CER in response to perceived organizational family support (at Time 1). Furthermore, employees with higher levels of CER tend to identify themselves more with their organizations, and have less psychological contract breach, and WFC (at Time 2) than do employees with low levels of CER in response to perceived supervisory family support (at Time 1). In the end, the implications, limitations, and future research directions were also discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The difficulty of balancing work and family life is a popular topic of study and analysis in both popular press and scholarly literature (Coyle-Shapiro and Shore 2007; Morrow 2011). Nowadays, employers tend to care more about their employees’ life standards and have started to consider the idea of “the best place for work” (McCarthy et al. 2010). Therefore, they tend to manage employees through a family-friendly company perspective. In the past decades, practitioners and scholars primarily have engaged in specific programmes and policies which support organizational members’ family needs (Hammer et al. 2009). More recently, this insight has changed to explore the significance of a supportive family-friendly (i.e. supervisor sensitive to work–family issues) organizational culture (Allen 2001; Jahn et al. 2003; McCarthy et al. 2010; Shih and Chuang 2013; Thompson et al. 1999). Despite many businesses’ claims that they provide work-life programmes, and put into practice certain policies, employee perceptions of their company’s actual practices can be considered differently (Allen 2001; Jahn et al. 2003). Thus, to understand the underlying mechanisms of all of the above, and to find out the roots of family support, it is necessary to delve into social and perceived organizational support theories (Eisenberger et al. 1986; House 1981) which are considered as the general framework of family support (Jahn et al. 2003).

Social support is defined as the resources available for others and the important tools for dealing with a variety of outcomes such as work–family conflict since they improve the ways in which we relate to stressors in different life spheres (Parasuraman et al. 1992). It has also been used to encourage and promote employees’ willingness to initiate self-described environmental activities and to develop and implement creative ideas that may positively affect the natural environment (Ramus and Steger 2000). Even in some studies social support seems to play a vital role in enhancing the employees’ perception of “risk-taking” in organizations, “a willingness to withstand uncertainty and mistakes as one explores new ideas, advocates unconventional or unpopular positions, or tackles extremely challenging problems without obvious solutions, in order to increase the likelihood of accomplishment” (Neves and Eisenberger 2014: 188). Nevertheless, three categories of social support are described in the literature. The first one is instrumental, which indicates the provision of actual aid and programmes; the second one is informational, which indicates communication about what resources are available, and the last one is emotional, which points to approval of an organizational member’s non-work related needs (House 1981) as well as “probably the most related form of social support to positive regard” (Carmeli and Russo 2016: 114). Being one of the “Micro-moves”, Carmeli and Russo (2016) call it; emotional expression could be the instruments of positive change that may support individuals to balance their work-home lives more effectively and successfully.

Parallel to these categories, Greenhaus and Parasuraman (1986) suggested some strategies to reduce the work–family conflict. Nelson and Quick (1991) also proposed a similar framework for organizational social support such as emotional support, informational support and instrumental support. It is generally thought that supports come from friends and family. Erera (1992), however, suggested that individuals expect social support from their work and that it is in the realm of individuals’ expectations to protect the balance between work and non-work domains. As an example, Hochschild (1997) emphasized that employees perceive their work environment as the centre of their lives, and get more support from their co-workers than from their family and friends outside of work.

Family-friendly programmes are particularly important for the organizations at the macro and micro levels (Carmeli and Russo 2016). At the macro level, these programmes demonstrate how an organization helps their employees to achieve a realistic balance between work and family life (Thompson et al. 2004). Therefore, these programmes provide a more dedicated workforce for an organization (Chiu and Ng 1999; Wang and Walumbwa 2007). From the micro level perspective, the family-friendly programmes implemented by HR such as dependent care and supervisor support can be used to reduce turnover rates (Batt and Valcour 2003; McCarthy et al. 2013); flexible policies can be used to reduce turnover rates (Batt and Valcour 2003) as well as stress in employees’ lives and absenteeism at work (Halpern 2005). Employees can balance their work and family roles due to these programmes (Batt and Valcour 2003; McCarthy et al. 2013). Thus, organizations which gain a competitive advantage by offering these programmes (e.g. leave policies or traditional dependent care) can also maintain a high level of job performance such as increase in market performance or profit-sales growth (Perry-Smith and Blum 2000) and productivityFootnote 1 (Halpern 2005; Judge and Colquitt 2004; Wang and Walumbwa 2007). Additionally, there are few studies that point out also other work-outcomes such as organizational identification or psychological contract breach. For example, a recent study by Stinglhamber et al. (2015) found a link between perceived organizational support and organizational identification. In another study He et al. (2014) asserted strong effect of perceived organizational support on organizational identification when exchange ideology of the employees was high. Finally, through a socioemotional perspective Aselage and Eisenberger (2003) discussed theoretically the interrelation between POS and psychological contracts.

Interestingly, the extant literature of support seems to have blurred boundaries in terms of distinguishing general organizational-supervisor support from family-specific organizational-supervisor support. Supervisor family support is the stage at which supervisors are eager to talk about family problems and to be flexible about life emergencies (Goff et al. 1990), and it has a critical role in work-life balance. Organizations may offer various family-friendly practices, but supervisors have a critical role in this process since employees’ supervision is an important factor in conveying the given organizational programmes. If supervisors do not convey the information and policies, the expected outcomes for greater employee work-life balance will not be fulfilled. Likewise, in a recent meta-analytic study it was found that the “policy availability was more strongly related to job satisfaction, affective commitment, and intentions to stay than was policy use” (Butts et al. 2013: 1). Therefore, organizational culture and manager training programmes are a way to increase the possibility that policies will be conveyed to all levels of the organization (Jahn et al. 2003; Thompson et al. 1992). The importance of supervisory support has been widely emphasized in the literature. For example, it is related to work–family conflict, and absenteeism (Goff et al. 1990); acts as a stress buffer for relationship-oriented individuals who perceive lack of support as stressful and symptom-provoking (Cummins 1990); boosts employee’s eco-creativity and eco-innovation in terms of “competence building, communication, rewards and recognition, and management of goals and responsibilities”; even better than organisational support (Ramus and Steger 2000: 623); is related to both objective and self-report measures of sleep quantity and quality (Crain et al. 2014); helps employees in need for caring when they are trying to handle their competitive personal and professional demands (Russo et al. 2015); helps to stabilize employees’ work and family lives especially when family friendly practices are low or absent (Hildenbrand 2016); could create work-to-family positive spillover effects as individual job resources for the employees (Straub et al. 2017); reveals a positive association with prosocial motivation and extrinsic motivation (Bosch et al. 2018). But in some studies the findings indicate a compensatory effect of supervisory support for family friendly practices at work; which means the supervisors could make a difference in the absence of family friendly practices. The effect of supervisors could also go to the extent of contributing to the employees’ perception of risk-taking in organizations. A study, mentioned in the preceding paragraphs, investigated how perceived organizational support (POS) could be related to employees’ risk taking behaviour and pointed the role of supervisors when they “strongly believed the organization was trustworthy in risk situations, employees’ POS had a stronger relationship with failure-related trust, which in turn, was related to risk-taking” (Neves and Eisenberger 2014: 187). Yet, there are also counter views with regards to the associated costs of these types of provisions to the employees in organizations (Wax 2004; Hammer et al. 2011; Hildenbrand 2016; Carmeli and Russo 2016) which will be discussed further.

Anyway, as organizational members distinguish the support coming from their organization and supervisors (Kottke and Sharafinski 1988; Jahn et al. 2003), both types of supports are used in this study. But again, this study is particularly concentrated on the organization and supervisor family support and examines whether perceptions of support are related to organizational identification, psychological contract breach, and work–family conflict.

Despite the studies that revealed variances with regard to the given consequences, other mediating or moderating effects might play significant roles, such as the emotions of employees. For example, in another meta-analytic study, Kossek et al. (2011) found some evidence that the effect size that explains the power of work–family-specific constructs of supervisor and organization support (− .32) presents that other variables might play significant roles compared to general supervisor and organization support’s effect size (− .08). The vast literature on perceived organization support generally stress social exchange theories to establish a research framework (e.g. Aselage and Eisenberger 2003; Stinglhamber et al. 2015) and even with mediating or moderator variables (e.g. He et al. 2014). The motivation to do this research is threefold; first, there have been very few efforts to integrate different moderators of the effects of perceived organization support on various work-outcomes in organizations (Sears et al. 2016). Second, the primary concern of emotion literature in organizations seems to be on the antecedents and consequences of individual affect (Rafaeli et al. 2009) and the role of emotions themselves as antecedents are scarce. Past studies reveal a growing interest in emotional and affective experiences at work. Similarly, given the evidence about its association with some certain physiological and psychological consequences, the importance of emotional regulation has also been emphasized in literature (Bono et al. 2007). And finally, the collectivist cultural codes of the Turkish society that entails a strong role of emotions in every aspect of their daily lives (e.g. Ozdasli and Aytar 2013) signal those emotions may play a significant role in the relationships.

Thus, to fulfil this gap, and by keeping the social exchange framework in mind, this study additionally draws on “affective infusion model” which emphasizes how the emotional states may affect the judgment processes of people; e.g. “positive emotional states often lead to more positive attitudes and negative emotional states lead to more negative attitudes” (Forgas 1995: 44) and on “functionalist perspective” that posits that the nature of emotions can be both “inherently regulatory and regulated” (Campos et al. 1994: 284) and integrated cognitive emotion regulation in the model as a moderator.

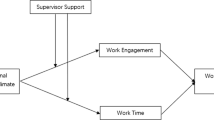

Finally, and the main contribution of the study is to test whether and how cognitive emotion regulation acts as a moderator among these relationships (see Fig. 1).

2 Theory and literature review

2.1 The effects of perceived organizational family support (POFS) and perceived supervisory family support (PSFS) on undermining work–family conflict

Inspired by demands-resources model of the work–family interface with demands more relevant in shaping conflict and resources more salient in predicting facilitation Seery et al. (2008) posit that it is important to investigate the relationship between work and family for two reasons. The imbalance between the two domains has been proven to cause undesirable consequences either in terms of job-related issues or family-related issues. Second, when the relationship is enhanced and balanced, the implications will be positive for both domains.

Work–family conflict refers to an individual’s role that makes it difficult to accomplish the demands of another role (Greenhaus and Beutell 1985). This conflict can be interpreted in two ways; namely, that work interferes with family, and second, that family interferes with work. Research indicates that a supportive organizational climate and supportive supervisors help with balancing work and family life (Allen 2001; Premeaux et al. 2007; Thomas and Ganster 1995; Thompson et al. 1999, 2004; Thompson and Prottas 2005). Norms that respect employees’ personal and family time are a part of supportive work–family cultures (Thompson et al. 1999). In this manner, research also shows that support from organizations and supervisors reduce work–family conflict (Carlson and Perrewé 1999; Selvarajan et al. 2013; Kossek et al. 2011). However according to Selvarajan et al. (2013) a family-supportive organizational climate seems to play a more important role in accounting for a reduction in work–family conflict than general organizational support. On the other hand, Moen and Yu (2000) indicate that having a supportive supervisor leads to higher life quality (coping/mastery) and lower work–family conflict, for both men and women. O’Driscoll et al. (2003) emphasize that employees with greater supervisor support reported less psychological strain than did employees with less support. Also, Ford et al. (2007) found that organizational support (including supervisor support) and work–family conflict were negatively correlated. Research shows that the concept of family interferes with work is less prevalent than work interferes with family (Eagle et al. 1997) and is more likely to be influenced by workplace factors (Anderson et al. 2002; Thompson et al. 2004) and by supportive supervisor behaviours (Hammer et al. 2009). Thus, this study focuses on both aspects to explain the relationship better, and it is hypothesized as follows;

Hypothesis 1a

Perceived organizational family support (POFS) is negatively related to work interferes with family (WIF).

Hypothesis 1b

Perceived supervisory family support (PSFS) is negatively related to work interferes with family (WIF).

Hypothesis 2a

Perceived organizational family support (POFS) is negatively related to family interferes with work (FIW).

Hypothesis 2b

Perceived supervisory family support (PSFS) is negatively related to family interferes with work (FIW).

2.2 The influence of POFS and PSFP on organizational identification, psychological contract breach

Perceived organizational support emphasizes the individual’s beliefs about the organizational contributions for their well-being (Eisenberger et al. 1986; Lauber and Storck 2016). The relationship between employees and their organizations/supervisors has been described in accordance with social exchange theory (Aselage and Eisenberger 2003; He et al. 2014; Stinglhamber et al. 2015). Therefore, perceived organizational support is considered as an important aspect in understanding the relationship between employees and the workplace, and is regarded by some researchers as central to understanding the job-related attitudes and the behaviours of employees (Shen et al. 2013). Some scholars have indicated that less research on the employee and employer/organization relationship has taken into account the role of organizational identification (Eisenberger and Stinglhamber 2011; Shen et al. 2013; Sluss et al. 2008). Organizational identification is defined as “perceived oneness between self and organization’’ (Ashforth et al. 2008), and most often the concept has been strongly related to organizational commitment, “affective commitment in particular” (Stinglhamber et al. 2015: 2). But some also argue that it is different from organizational commitment (Van Knippenberg and Sleebos 2006) because it describes a cognitive connection that emphasizes a relationship between the individual and the organization in terms of one’s self-concept (Ashforth et al. 2008; Pratt 1998). Group engagement model emphasizes that perceived organizational support enhances the employees’ organizational identification and makes different contributions to the employee’s sense of self (Tyler and Blader 2003). Shore and Shore (1995) also found that the perception of organizational support provides employees with important information about their relationship to the workplace. In addition to this view, Sluss et al. (2008) emphasized that organizational support increases the organization’s perceived attractiveness and organizational identification. In addition, other researchers also show a positive relationship between perceived organizational, supervisory support and organizational identification (Edwards and Peccei 2010; Marique et al. 2013; Sluss et al. 2008; Shen et al. 2013; Zagenczyk et al. 2013; Kurtessis et al. 2015). But a positive relationship between perceived organizational and supervisory family support and organizational identification deserves a well-grounded answer. Thus, it is hypothesized in this study that:

Hypothesis 3a

Perceived organizational family support (POFS) is positively related to organizational identification.

Hypothesis 3b

Perceived supervisory family support (PSFS) is positively related to organizational identification.

Psychological contract is defined as the reciprocal exchange of individuals’ beliefs with their organizations regarding the terms and conditions about the promises between employee and employer (Rousseau 1989). Perceived psychological contract breach occurs when an employee receives less than a given promise (Robinson and Morrison 2000). As indicated by Morrison and Robinson (1997), breach is an antecedent of violation. In general, the research on psychological contracts has focused mainly on analysing the results of psychological contract breach (Kiewitz et al. 2009; Restubog et al. 2008; Suazo and Turnley 2010). The psychological contract breach domain is particularly important because meeting employees’ expectations remains as a challenging issue for many organizations (Turnley and Feldman 1999). Research emphasizes that the effect of psychological contract breach can be long-lasting and difficult to repair (Conway et al. 2011; Robinson et al. 1994; Robinson and Morrison 2000). In this context, a failure by the organization, i.e. its representative, or supervisor (Dabos and Rousseau 2004), about the promises made is likely to have deleterious consequences. In similar vein the relationship between perceived organizational support and psychological contract breach is most often based on social exchange theory (Aselage and Eisenberger 2003). As indicated by Dabos and Rousseau (2004), organizations and supervisors are the immediate outcomes of psychological contract breach because both of these entities are involved in the formation of psychological contracts. Regardless of formal contracts, the pervasive effects of combining professional and family responsibilities lead employees to expect family-related support from organizations. In collectivist countries like Turkey, employees have no courage to discuss these matters explicitly with their supervisors. Instead they expect their supervisors to see and recognize the things which they are enduring. When these expectancies are not realized, they may feel frustrated and may well perceive an organizational contract breach (OCB). Research provides enough evidence to show how supportive supervisors can increase employees’ perceptions as to whether their organizations are sensitive to their family commitments (Russo and Waters 2006). In the literature, perceptions of psychological contract breach have been associated with many attitudes and behaviours that have generally included negative ramifications for employees and employers (Zhao et al. 2007). In contrast, little research has examined the predictors of perceived psychological contract breach (PCB) (e.g., Suazo and Turnley 2010) and some studies indicate that perceived organizational and supervisory support are negatively related to perceived psychological contract breach (Stoner et al. 2011; Bhatnagar 2013; Kurtessis et al. 2015). However, a direct link between perceived organizational family support–perceived supervisory family support and psychological contract breach is missing. To find support for the relationship between perceived organizational family support–perceived supervisory family support and psychological contract breach, it is hypothesized in this study as follows;

Hypothesis 4a

Perceived organizational family support (POFS) is negatively related to psychological contract breach (PCB).

Hypothesis 4b

Perceived supervisory family support (PSFS) is negatively related to psychological contract breach (PCB).

2.3 The moderating effect of employees’ cognitive emotion regulation

Despite the variance that accounts for every type of perceived family support on work–family conflict (Hammer et al. 2011), how and by which mechanisms it influences still remain, to some extent, a mystery and more research on this is required (Armeli et al. 1998; Sears et al. 2016). Some studies point out the roles of certain moderators such as self-monitoring interventions in amplifying the perception of family support in organizational settings (Kossek et al. 2011; Sears et al. 2016). There are also propositions in terms of cognitive interferences that may mediate these relationships (Ford et al. 2007). As discussed before, the relationship between perceived organizational support and its outcomes were usually based on social exchange theories. Thus, by keeping the social exchange framework in mind, this study additionally draws on “affective infusion model (AIM)” and on “functionalist perspective (FP)”. According to AIM, the emotional states have the power to alter the judgment processes of people; e.g. “positive emotional states often lead to more positive attitudes and negative emotional states lead to more negative attitudes” (Forgas 1995: 44); based on this, it was proposed that cognitive emotional regulation of the employees may enhance or undermine the effects of perceived organizational family support and perceived supervisory family support. What’s more, some researchers even assumed that individuals with greater emotion regulation ability may feel less frequent negative emotion and more frequent positive emotion; hence, it was even possible for them to experience even greater optimism (Trejo et al. 2015). Secondly, FP posits that the nature of emotions can be both “inherently regulatory and regulated” (Campos et al. 1994: 284) and through this, it was also argued that when the effect of perceived organizational family support and perceived supervisory family support were weak, employees with higher cognitive emotional regulation may neutralize and even compensate this weak effect.

Cognitive emotion regulation builds on appraisal theories of psychology that “the way we evaluate an event determines how we react emotionally” (Lazarus 1999: 87). What is meant here is that certain emotions are not triggered by certain events but that those emotions are merely caused by the people’s subjective evaluations of the events (Lazarus and Folkman 1984; Ortony 1988; Scherer 1988; Lazarus 1991). Troy and Mauss (2011) believe that the way a person can use cognitive emotion regulation skilfully depends on a number of situational and individual factors which are learnt in time and thus, can be flexibly applied across a wide range of emotional contexts when needed and accordingly, the amount of emotional reaction may depend on to what extent they evaluate the event (Troy and Mauss 2011). In other words, certain cognitive emotion regulation strategies may be developed, and consequently lend themselves to appraisal changes that lead to a more effective management of one’s emotions and the adoption of different emotional reactions, and vice versa. From here, cognitive emotion regulation can be defined as “changing one’s attention to or one’s appraisal of a situation in order to change an emotion’s duration, intensity, or both (Ochsner and Gross 2005).

Studies focused on cognitive emotion regulation constantly report that the emotion regulation not only contributes positively to physical health but also to emotional well-being (John and Gross 2004; Jorgensen et al. 1996). Additionally, the use of reappraisal strategies is related to positive emotional experiences and better intrapersonal practices (Gross and John 2003) as well as to an increase in positive feelings and adaptive behaviours while decreasing negative emotions (Rottenberg and Gross 2003).

The intangible dimension of organizational family support is assumed to be linked to the perceptions of emotional support (Thompson et al. 2004). Thus, could both perceived organizational family support and perceived supervisory family support are regarded as certain types of interventions that help the employees to increase their reappraisal strategies by creating a positive and meaningful work environment? Although discussed within the framework of family emotional labour (Seery et al. 2008), emotional enhancement could provide the answer since it involves all the “efforts to make others feel happy and content and enhance their self-esteem” (Seery and Corrigall 2009: 798). When supervisors discuss family-related matters with their subordinates and even provide tangible and intangible support, this may enhance employees emotionally by generating a positive organizational setting. However, these views could point to the existence of a mutual relationship which could be a topic of another study.

Taking into consideration that both perceived organizational family support and perceived supervisory family support represent the organizational context, and that the intensity of the subjective appraisal depends on how far people perceive family-related support from that context, we propose that higher cognitive emotion regulation may enhance the perceptions of support, and in return, these contexts may help to increase the adoption of more resilient appraisal strategies. In the end, heightened appraisal strategies may conduce negatively to WFC and psychological contract breach but positively to organizational identification.

Thus, in the present study the following hypotheses are set forth:

Hypothesis 5a

Cognitive emotion regulation will moderate the relationships between perceived organizational family support (POFS) and organizational identification (O-ID) in such a way that the relationship will be stronger for higher emotion regulation than for lower cognitive emotion regulation.

Hypothesis 5b

Cognitive emotion regulation will moderate the relationship between perceived supervisory family support (PSFS) and organizational identification (O-ID) in such a way that the relationship will be stronger for higher emotion regulation than for lower cognitive emotion regulation.

Hypothesis 6a

Cognitive emotion regulation will moderate the relationship between perceived organizational family support (POFS) and psychological contract breach (PCB) in such a way that the relationship will be stronger for higher emotion regulation than for lower cognitive emotion regulation.

Hypothesis 6b

Cognitive emotion regulation will moderate the relationship between perceived organizational family support (POFS) and psychological contract breach (PCB) in such a way that the relationship will be stronger for higher emotion regulation than for lower cognitive emotion regulation.

Hypothesis 7a

Cognitive emotion regulation will moderate the relationship between perceived organizational family support (POFS) and work interferes with family (WIF) in such a way that the relationship will be stronger for higher emotion regulation than for lower cognitive emotion regulation.

Hypothesis 7b

Cognitive emotion regulation will moderate the relationship between perceived organizational family support (POFS) and family interferes with work (FIW) in such a way that the relationship will be stronger for higher emotion regulation than for lower cognitive emotion regulation.

Hypothesis 7c

Cognitive emotion regulation will moderate the relationship between perceived supervisory family support (PSFS) and work interferes with family (WIF) in such a way that the relationship will be stronger for higher emotion regulation than for lower cognitive emotion regulation.

Hypothesis 7d

Cognitive emotion regulation will moderate the relationship between perceived supervisory family support (PSFS) and family interferes with work (WIF) in such a way that the relationship will be stronger for higher emotion regulation than for lower cognitive emotion regulation.

3 Research method

To test the stated hypotheses, a survey employing a convenience sampling method was conducted in high-tech organizations in Kayseri-Turkey; a mid-Anatolian metropolitan city with huge and complex industry district such as hi-tech aviation. A large group of employees were initially selected from the companies located there to participate through stratified random sampling based on their department size and type to ensure representation across the organization and its various sub-unit types and expertise. Participants were required to work full-time within the organization and have frequent and direct relations with their supervisors. Data for this study were part of a longer, multiway survey, investigating the employer-employee relationship (see Kiewitz et al. 2009, Study 1; Zagenczyk et al. 2011 Study 2). The dependent and independent variables along with moderator were collected at different times. Thus, three surveys were conducted 3 weeks apart to reduce the influence of common method variance (CMV) in single source data. At Time 1, three surveys were sent to assess demographic, independent and moderator variables (Perceived Organizational and Supervisory Family Support) and 482 employees completed the surveys, in which 980 questionnaires were distributed, corresponding to a response rate of 49.1%. A total of 271 respondents completed the Time 2 survey, in which 500 questionnaires were distributed generating a response rate of 54%. This time dependent variables were sent out 2 weeks apart (Organizational Identification, Psychological Contract Breach, Work–Family Conflict). Respondents at Time 2 were mostly male (63.4%), and their average age was 44.7 years. Participants had spent an average of 12.7 years in their current job. Respondents were employed by different organizations in positions such as administrative assistant, communications specialist, computer specialist, consultant, programme officer, engineer, and customer service. In terms of education, 52% of employees had a junior high or a high school degree, 31% had an undergraduate degree, and 17% had a graduate degree.

To determine sampling bias influences, the demographics and perceived organizational and supervisor family support responses reported by the participants who responded to both Time 1 and Time 2 surveys (n = 271) were compared to those reported by individuals who responded only to the Time 1 survey (n = 482). The MANOVA results showed no significant differences between the two groups.

3.1 Measures

3.1.1 Perceived organizational family support

To assess perceived organizational family support, the ten-item Perceived Organizational Family Scale, which was developed by Jahn et al. (2003), was used in this study. The scale measures perceptions of instrumental, informational, and emotional support by an organization. Sample items include, “My organization puts money and effort into showing its support of employees with families” and “It is easy to find out about family support programmes within my organization”. All items were measured on a seven point Likert scale ranging from 1 = “Strongly Disagree”, to 7 = “Strongly Agree”. The internal consistency reliability estimate was .92.

3.1.2 Perceived supervisory family support

To assess perceived supervisory family support, the six-item Perceived Supervisory Family Scale, which was developed by Fernandez (1986) was used in this study. An example item is, “My supervisor understands if someone has to leave early or come in late due to a family emergency”. Items were rated on a seven point Likert scale ranging from 1 = “Strongly Disagree”, to 7 = “Strongly Agree”. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .89.

3.1.3 Cognitive emotion regulation

To assess cognitive emotion regulation, the six-item scale which was developed by Gross and John (2003) was used. An example item is, “When I am faced with a stressful situation, I make myself think about it in a way that helps me stay calm”. Items were rated on a seven point Likert scale ranging from 1 = “Strongly Disagree”, to 7 = “Strongly Agree”. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .74.

3.1.4 Organizational identification

To assess organizational identification (O-ID), the six-item scale, which was developed by Kreiner and Ashforth (2004) was used. An example item is, “This organization’s successes are my successes”. Items were rated on a seven point Likert scale ranging from 1 = “Strongly Disagree” to 7 = “Strongly Agree”. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .79.

3.1.5 Psychological contract breach

To assess psychological contract breach (PCB), the five-item scale, which was developed by Robinson and Morrison (2000) was used. In this measure, participants evaluated the degree to which they perceived that the organization provided, relative to what they were promised. An example item is, “I have not received everything promised to me in exchange for my contributions”. Items were rated on a seven point Likert scale ranging from 1 = “Strongly Disagree”, to 7 = “Strongly Agree”. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .80.

3.1.6 Work–family conflict

To assess work–family conflict, two types of sub-scales were used in this study. The first one assessed how much work interferes with family (WIF), and the second assessed how much family interferes with work (FIW). For WIF, the four-item scale which was developed by Kopelman et al. (1983) was used. An example item is, “After work I come home too tired to do some of the things I would like to do”. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .79.

For FIW, the four-item scale developed by Gutek et al. (1991) was used. An example item is, “My personal demands are so great that it takes away from my work”. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .75. Items in these scales were rated on a seven point Likert scale ranging from 1 = “Strongly Disagree”, to 7 = “Strongly Agree”. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .80.

3.2 Initial analyses-common method variance problem

To assess whether the common method variance (CMV) had an influence on the data, Harman’s (1967) one-factor test was used. In this analysis, all the items (i.e., POFS, PSFS, OI, PCB, WIF, FIW, and emotion regulation) were entered into an exploratory factor analysis to determine the number of factors needed to account for the majority of variance in the items. Common method variance is likely to occur if either one factor emerges from the analysis or one general factor accounts for the majority of variance (Podsakoff et al. 2012). The unrotated solution showed that eight factors were attained in the analysis which explained 71.17% of the total variance, with the first factor accounting for only 29.48% of this variance. This result indicates that common method variance was unlikely to pose a threat to the validity of the data.

In addition, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was also conducted to assess the measurement properties of the variables. All of the constructs were permitted to have a free correlation with each other. The fit indices showed that data fit the model well (χ2 = 71.98; CFI = .92; TLI = .91; RMSEA = .06). The standardized factor loadings of all items met the minimum suggested value of .70 (Fornell and Larcker 1981).

3.3 Discriminant validity

In this study, we first assessed the discriminant validity of the measures using Average Variance Extracted (AVE) tests (Fornell and Larcker 1981). Based on a 3-factor model using AMOS with maximum likelihood with promax rotation, following the procedure set forth by Fornell and Larcker (1981), we calculated the variance extracted for each measure as well as the squared correlations between the latent constructs as shown in the diagonal of Table 1. The all variance extracted for the study variables seem to be higher than .50, which is an expected value showing the discriminant validity of the used measures, thereby establishing discriminant validity (Fornell and Larcker 1981).

4 Findings

4.1 Results and discussion

Table 1 reports the descriptive statistics and correlations for all of the variables in this study. As can be seen from the Table 1, zero order correlations are in the expected direction. As shown in Table 1, there are positive relations between gender and perceived organizational family support (r = .17; p < .05); gender and PSFS (r = .15; p < .05); gender and O-ID (r = .22; p < .05), gender and cognitive emotion regulation (CER) (r = .16; p < .05), and finally gender and FIW (r = .11; p < .05). In addition, we also observed that the perceived organizational family support was the highest mean value (5.03) in all of the variables used in this study.

Results of regression analysis are presented in Table 2. As indicated by Aiken and West (1991), the independent variables were centered at their means prior to the creation of interaction terms. The control variables were entered in all three steps of the hierarchical regression analyses.

4.2 Findings regarding hypotheses

To test the hypotheses, moderated hierarchical regression analysis was conducted. In the analyses, age, gender and job experience were controlled as they may be related to the dependent variables (e.g., Hunter and Thatcher 2007; Bal et al. 2008; Dalton and Radtke 2012). As has been previously mentioned, the independent variables were centered before interaction terms were calculated. Also, significant interactions were plotted and simple slopes were calculated for the moderator at one standard deviation below and above the mean, using the procedures recommended by Aiken and West (1991).

Hypotheses 1a, b, which predicted that perceived organizational and supervisory family support would be positively related to organizational identification, were supported (β = .41, p < .001; β = .54, p < .001; see Step 2, Table 2).

Hypotheses 2a, b, which predicted that perceived organizational and supervisory family support would be negatively related to psychological contract breach, were supported (β = − .19, p < .05; β = − .37, p < .001). Hypotheses 3a, b, which predicted that perceived organizational and supervisory family support would be negatively related to work interferes with family, were supported (β = − .39, p < .001; β = − .35, p < .001).

Hypothesis 4b, which predicted that perceived supervisory family support would be negatively related to family interferes with work, was also supported (β = − .33, p < .001). However, Hypothesis 4a, which predicted that perceived organizational family support would be negatively related to family interferes with work, was not supported.

Hypotheses 5a, b, which predicted that cognitive emotion regulation would moderate the relationships between perceived organizational and supervisory family support and organizational identification, were supported (β = .61, p < .001; β = .52, p < .001). In order to illustrate graphically the significant moderation effects uncovered in the analyses, Stone and Hollenbeck’s (1989) methodology was used, which indicates plotting two slopes: one at one standard deviation below the mean, and one at one standard deviation above the mean. This plot is shown in Fig. 2.

The simple slope tests suggest that organizational identification increases both low and high emotion regulation as both of them are valid for perceived organizational and supervisory family support. These effects are stronger when cognitive emotion regulation is high, and support the Hypotheses 5a, b.

Hypothesis 6a, which predicted that cognitive emotion regulation would moderate the relationship between perceived organizational family support and psychological contract breach (PCB), was not supported. The interaction term (POFS*CER) was significantly associated with psychological contract breach (β = .10, p > .05), after accounting for control variables and main effects. Thus, although perceived organizational family support (β = − .19, p < .05) and emotion regulation (β = − .22, p < .01) were significantly associated with PCB, the interaction between the two variables was not.

Hypothesis 6b, which predicted that cognitive emotion regulation would moderate the relationship between perceived supervisory family support and psychological contract breach, was supported (β = 48, p < .001). The significant moderation effect is shown in Fig. 3.

The simple slope tests suggest that psychological contract breach decreases for both low and high cognitive emotion regulation. As seen in Fig. 3, the effect is stronger when cognitive emotion regulation is high, and thus this supports Hypothesis 6b.

Hypotheses 7a, b which predicted that cognitive emotion regulation would moderate the relationships between perceived organizational and supervisory family support and work interferes with family (WIF), were supported (β = .39, p < .001; β = .30, p < .001). The significant moderation effects are shown in Fig. 4.

The simple slope tests suggest that work interferes with family decreases for both low and high emotion regulation as both for perceived organizational and supervisory family support. These effects are stronger when emotion regulation is high, supporting the Hypotheses 7a, b.

Hypothesis 7c, which predicted that cognitive emotion regulation would moderate the relationship between POFS and FIW, was not supported. The interaction term (POFS*CER) was not significantly associated with FIW (β = .08, p > .05), after accounting for control variables and main effects.

Hypothesis 7d, which predicted that cognitive emotion regulation would moderate the relationship between PSFS and FIW, was supported (β = .42, p < .001). The significant moderation effect is showed in Fig. 5.

The simple slope tests suggest that family interferes with work decreases for both low and high emotion regulation, as for perceived supervisory family support. As seen from Fig. 5, the effect is stronger when emotion regulation is high, thus supporting Hypothesis 7d.

5 Discussion

This study examined the relationship between perceived organizational and supervisory family support and several outcome variables. Furthermore, the role of cognitive emotion regulation was examined as a moderator on these relationships. Unlike the findings of recent meta-analytic studies (i.e. Butts et al. 2013) that posit inconsistent positive relationships between work–family policies and employee attitudes, our analyses showed that perceptions of organizational and supervisory family support were positively related to organizational identification, and negatively related to work interferes with family, family interferes with work, and psychological contract breach. The inconsistency among the findings is associated with certain methodological deficiencies such as the inclusion of both availability and perception of work–family policies only or the use of them in organizational contexts only. Additionally, most studies have related these policies to employee work attitudes without exploring the underlying mechanisms, such as possible mediators (Butts et al. 2013) or moderators that might play important roles. Interestingly, organizational support for family appears to be important in enhancing employee attitudes more than formal policies (Butts et al. 2013). Our study showed the same results and that the existence of a moderator seems to increase this relationship.

On the other hand, against the findings that the employees are highly valuing family friendly interventions, the argument regarding the cost of these practices in organizations is still a hot topic (Wax 2004; Heywood et al. 2007; Smeaton et al. 2014; Hildenbrand 2016). Particularly in time of turbulences and economic downfalls there seems to be a general proclivity to reduce even cut the resources allocated for these types of practices (Riva 2013; Carmeli and Russo 2016). In some countries the reform initiatives to provide family support at work suffered from resistance by firms due to its high costs (Wax 2004). Furthermore, the inconclusive evidence that present support to increased firms’ financial performance is still vague (Bloom et al. 2011). Plus, the firms’ ultimate motives may be unrelated to financial gains but rather to employees’ morale and talent retention. There are also debates that evolve around the idea of an “implicit market” where employees may face relatively low wages for their demand of family-friendly practices as a type of trade-off (Fakih 2014). However, it should be born in mind that these provisions are believed to be as gifts which employers are showing their care towards the employees’ family responsibilities and in exchange for that, employees are willingly accepting wage offsets. It is no doubt that family-friendly practices seem to be perceived positively in many ways. But the interaction between institutional arrangements and organizational conditions could affect the provisions of such supports. Thus, in reality the implementations change in shape, there are even variations within countries, and there is a requirement to “explain how and why certain HRM practices are perceived as helpful by men and women in different circumstances” (Lew and Bardoel 2017: 84). Or even interestingly, some researchers found “differential effects” for both sexes (Hammer et al. 2005); i.e. men seemed to use supports less likely. Some studies report that firms with a higher proportion of female managers and more skilled workers, as well as well-managed firms, tend to implement more family-friendly practices (Bloom et al. 2011: 343) but still, the interplay between institutional arrangements and the organizational conditions mentioned above deserve further investigation. For example, during field visits in our study, we learnt that few organizations that employ minimum 100 and more had either provided children care units inside their facilities or had the intention to do so in near future because of the law.

Anyway, the results of our study indicated that employees with higher levels of cognitive emotion regulation tended to identify themselves more with their organizations and less with work interferes with family (at Time 2) than did employees with low levels of cognitive emotion regulation in response to perceived organizational family support (at Time 1). Furthermore, employees with higher levels of cognitive emotion regulation tended to identify themselves more with their organizations, and have less psychological contract breach, and work–family conflict (at Time 2) than did employees with low levels of cognitive emotion regulation in response to perceived supervisory family support (at Time 1).

The hypotheses for the moderation effects of cognitive emotion regulation on the relationships between perceived organizational family support-psychological contract breach, and perceived organizational family support-family interferes with work, were not supported. Although these variables are related, the interaction terms (POFS*CER) were not significantly associated with psychological contract breach and family interferes with work, after controlling for control variables and the main effects. Thus, high and low cognitive emotion regulation did not differ in these relationships. These findings were not in the anticipated direction that we thought while establishing the hypotheses. It should occur from the sample that was used in this study. Thus, in order to extend and interpret these findings, different samples from other sectors, or cultural effects should be added to the given model.

6 Theoretical implications

As discussed earlier in the introduction part, supervisory support has been proven to be effective in a variety of organizational outcomes. But so far, to our knowledge, hardly any study included the organization and supervisor family support together and examined whether perceptions of support are related to organizational identification, psychological contract breach, and work–family conflict. Thus, this study contributes to perceived organizational family support literature in several ways. First, it contributes to the field by providing a description and analysis of the influence of perceived organizational and supervisory family support, and the findings mesh with and extend previous theoretical and empirical research efforts. This study is the first to analyse the interaction effects of cognitive emotion regulation on the perceived organizational/supervisory family support and identification, and perceived psychological contract/work family conflict relationships. Second, this study separated organizational family support into two parts as given by organization and supervisor in order to explain whether they have similar or different consequences on the dependent variables. Third, the data collection procedure was designed so that the measure of perceptions of organizational and supervisory family support, organizational identification, psychological contract breach, work interferes with family, and family interferes with work were gathered at different times, and a time lag was given to minimize common method biases.

To sum up, this article contributes prior researches in several ways. The two laborious meta-analytical researches, one in 2015 (Kurtessis et al. 2015) and the other in 2016 (Sears et al. 2016), revealed a variety of outcomes except organizational identification and psychological contract breach; even recent studies with regards to family related POS and supervisor POS such as Matthews and Toumbeva’s (2015). The literature regarding the outcomes for this stream seems to be missing. Besides, psychological contract was looked into as an antecedent that may have influenced POS in organizations (Kurtessis et al. 2015). Additionally, those studies didn’t look at family related POS but general POS. A distinction is required. Many supervisors and firms are gradually changing their attitude and cultures in becoming more explicitly supportive of work and family. And there are calls for new studies that enable researchers to explicitly capture the role of supervisor leadership regarding these relatively newer and evolving work–family issues at workplace (Kossek et al. 2011). Moreover, the basic theory which most of these studies grounded is social exchange theory. Different and other relevant theoretical relationships (e.g. in this study: “affective infusion model” and “functionalist perspective”) might help to enhance and enrich this vein of literature (e.g. “conservation of resources” or “buffering effect”). Examining cognitive emotion regulation as a predictor of some outcome variables is a new development in perceived organizational and supervisory family support research. It may help to explain why the perception of perceived organizational family support may vary from one employee to another, particularly when employees are in seemingly similar situations with a common supervisor or when they are members of the same work group. For example in some studies it was found that emotion regulation may cause to experience decreased job satisfaction as well as increased stress, and with the existence of supervisors who exhibit transformational leadership skills these negativities were less likely to surface (Bono et al. 2007).

7 Practical implications

The study gave clues on the usability of some intervention tools for the practitioners in organizations. The vast literature demonstrates that cognitive emotional regulation interventions are being used in the preventions of depressions and even in physical illnesses. Eventually, with an increasing rate, the focus has been shifted on the emotions of employees and the mechanisms to grasp how they affect the work-outcome. Within this context, interventions such as mindfulness-based, emotion-focused, and emotion regulation therapies may provide fruitful consequences for both employers and employees. Similarly, supervisor training to increase support for family is also gaining a prominent importance by work–life experts (Hammer et al. 2011). As this study results suggest, employee emotions are important. It should be born in mind that once induced, emotions have the power to affect judgment, decision making, person perception, attention, and memory— shortly all cognitive processes (Forgas and Bower 1987).

Lastly, as discussed before by some studies (Hildenbrand 2016) regarding the high cost of family supported practice implementations, such as on-site childcare centres, it could be useful to conduct cost-benefit analyses first and then determine whether training of supervisors (supervisors that are low on family supporting behaviours) is more cost-effective. Additionally, during economic crises and turbulent periods, there is a general proclivity to cut resources (Carmeli and Russo 2016); these types of trainings might be more fruitful and practical. In some countries, however, like in Turkey, it is imperative to provide these services in accordance with national regulations. It should be kept in mind that, although there is a relationship between family supported practices in organisations and increased employee performances, some evidence reveals this may depend on the quality of management practices (Bloom et al. 2011).

8 Limitations and future research

Like most other studies, this study has several limitations. First, it has been conducted in a Turkish setting. Therefore, in order to avoid an underestimation of the impact of deeply rooted societal norms (Hofstede 2001), it would be helpful to replicate this research in other countries. Another limitation is the cross-sectional nature of the study. This implies that the suggested relationships in our research model are based on theory and previous empirical findings, and cannot be interpreted causally. In addition, self-reported data can be considered as a limitation. However, the use of self-reports is the traditional method for collecting data on perceived organizational family support, perceived supervisory family support (e.g., Marique et al. 2013; Raja et al. 2004; Thompson et al. 2004). While this concern cannot be excluded, the individual is typically the most appropriate (and sometimes only) source of information regarding the constructs under investigation here. Thus, the use of self-reported measures seems the most accurate way as it concerns the main purpose of this research, which was to examine employees’ perceptions.

The results of this study point to the need for additional research that examines the role of moderators (e.g. “The Role of Family Supportive Organizational Culture as a Boundary Condition as in Rafcanin et al. 2017) of relations between perceived organizational and supervisory family support and assumed consequences (e.g., employee behaviours). It may follow a variety of interesting directions. As previously discussed, tackling with cognitive emotion regulation as a predictor of some outcome variables is a new development in perceived organizational and supervisory family support research. It may help to explain the variation of perceived organizational family support among the employees, particularly when employees are in seemingly similar situations with a common supervisor or when they are members of the same work group. In the analyses, age, gender and job experience were controlled as it may have related to the dependent variables (e.g., Bal et al. 2008; Dalton and Radtke 2012; Hunter and Thatcher 2007). Thus, these characteristics were included as control variables in the analyses, but it would be better to evaluate the impact of these and other variables on the perceived organizational and supervisory family support in additional research.

The findings of this study demonstrate that perceptions of organizational family support have an important role in integrating the organizations into their self-concept with positive implications for employees’ emotional attachment to the company. Results also indicate that employees who perceive high organizational family support have an enormous contribution to the organization. Such perceptions can be expanded through human resources, communication and providing necessary resources and job security (Eisenberger and Stinglhamber 2011). But which gender reciprocates more, has not been investigated in this study. Some findings point to the idea that women reciprocate to a greater extent than men (Kurtessis et al. 2015). Future research may wish to look at this topic.

It can also be concluded that the knowledge gained by research on the assumed relations between perceived organizational and supervisory family support and employee behaviours may be enhanced by considering potential moderators of these links. Although this study focused on employee cognitive emotion regulation as a moderator, other possible moderators should also be taken into the consideration. For example, variables such as mindfulness awareness, hardiness, and mental toughness may moderate the relations between perceived organizational family support and various work-outcomes. In their laborious meta-analysis that aggregated antecedents of WFC and FWC, Michel et al. (2011) could hold only two personality related variables; internal locus of control and negative affect/neuroticism. Other personality based factors as independent variables also appear to be promising as a direction for future inquiries (e.g. Core Self-Evaluations or Five Factor Model).

Research demonstrates that work interferes with family is more prevalent than family interferes with work (Eagle et al. 1997) and work interferes with family is more likely to be influenced by workplace factors (Anderson et al. 2002; Thompson et al. 2004) and supportive supervisor behaviours (Hammer et al. 2009). Thus, future research may wish to consider both work and family conflicts while establishing their models.

Communication and interaction can be a positive tool to manage negative perceptions that can occur because of individual tendencies. Although we do not consider communication as part of our study, however, we suggest that individual differences between employees should be taken into consideration by supervisors. Research indicates that formal family-friendly organizational polices have less effect on work–family conflict than supportive work–family culture and informal support (Premeaux et al. 2007), and perceived organizational support encourages employee dedication to their organizations by fulfilling socio-emotional needs such as affiliation and emotional support (Eisenberger et al. 1986). Therefore, establishing a closer communication framework with employees will provide greater utility for both sides. It has been emphasized that employees can develop strong relationships not only with their organization but also with their supervisor or their workgroup (e.g., Becker 1992; Christ et al. 2003; Riketta and van Dick 2005). Thus, future research should examine whether the relationships found in the present study may be extended and applied to other organizational fields. In addition, a cross-cultural comparison of perceived organizational family support in future research would be a valuable contribution to the knowledge in this domain.

In conclusion, companies may presume that family supportive services are costly (Meyer et al. 2001) but to motivate employees to attain organizational goals as well as to contribute to their general well-being, a family-friendly working context seems to play a critical role (Lauber and Storck 2016). The same is true of a family-supportive supervisors. Lastly, this study and others (Feierabend et al. 2011) provide evidence that supports the idea that investment in such services can pay off. And the more significant results the organizations receive, the more they will show willingness to provide such supports in the future (Hammer et al. 2005).

Change history

09 March 2019

Under Table 1, the explanation regarding the dummy variables that represent gender is reverse coded.

Notes

Halpern (2005): 167 posits that time-flexible policies may help employees have better health, and hence the cost of health care is reduced. So in the end fewer absences and late days may translate into higher productivity.

References

Aiken LS, West SG (1991) Multiple regressions: testing and interpreting interactions. Sage, Newbury Park

Allen TD (2001) Family-supportive work environments: the role of organizational perceptions. J Vocat Behav 58(3):414–435

Anderson SE, Coffey BS, Byerly RT (2002) Formal organizational initiatives and informal workplace practices: links to work–family conflict and job-related outcomes. J Manag 28(6):787–810

Armeli et al (1998) Perceived organizational support and police performance: the moderating influence of socioemotional needs. J Appl Psychol 83(2):288–297

Aselage J, Eisenberger R (2003) Perceived organizational support and psychological contracts: a theoretical integration. J Organ Behav 24(5):491–509

Ashforth BE, Harrison SH, Corley KG (2008) Identification in organizations: an examination of four fundamental questions. J Manag 34(3):325–374

Bal et al (2008) Psychological contract breach and job attitudes: a meta-analysis of age as a moderator. J Vocat Behav 72(1):143–158

Batt R, Valcour PM (2003) Human resources practices as predictors of work–family outcomes and employee turnover. Ind Relat 42(2):189–220

Becker TE (1992) Foci and bases of commitment: are they distinctions worth making? Acad Manag J 35(1):232–244

Bhatnagar J (2013) Mediator analysis in the management of innovation in Indian knowledge workers: the role of perceived supervisor support, psychological contract, reward and recognition and turnover intention. Int Hum Resour Manag 25(10):1395–1416

Bloom N, Kretschmer T, Van Reenen J (2011) Are family–friendly workplace practices a valuable firm resource? Strateg Manag J 32(4):343–367

Bono JE, Foldes HJ, Vinson G, Muros JP (2007) Workplace emotions: the role of supervision and leadership. J Appl Psychol 92(5):1357–1367

Bosch MJ, Heras ML, Russo M, Rofcanin Y, Grau MG (2018) How context matters: the relationship between family supportive supervisor behaviours and motivation to work moderated by gender inequality. J Bus Res 82:46–55

Butts MM, Casper WJ, Yang TS (2013) How important are work–family support policies? A meta-analytic investigation of their effects on employee outcomes. J Appl Psychol 98(1):1–125

Campos et al (1994) A functionalist perspective on the nature of emotion. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev 59(2/3):284–303

Carlson DS, Perrewé PL (1999) The role of social support in the stressor-strain relationship: an examination of work–family conflict. J Manag 25(4):513–540

Carmeli A, Russo M (2016) The power of micro-moves in cultivating regardful relationships: implications for work–home enrichment and thriving. Hum Resour Manag Rev 26(2):112–124

Chiu WCK, Ng CW (1999) Women-friendly HRM and organizational commitment: a study among women and men of organizations in Hong Kong. J Occup Organ Psychol 72(4):485–502

Christ et al (2003) When teachers go the extra mile: foci of organisational identification as determinants of different forms of organisational citizenship behaviour among school teachers. Br J Educ Psychol 73(3):329–341

Conway N, Guest D, Trenberth L (2011) Testing the differential effects of changes in psychological contract breach and fulfilment. J Vocat Behav 79(1):267–276

Coyle-Shapiro JAM, Shore LM (2007) The employee-organization relationship: where do we go from here? Hum Resour Manag Rev 17(2):166–179

Crain et al (2014) Work–family conflict, family-supportive supervisor behaviors (FSSB), and sleep outcomes. J Occup Health Psychol 19(2):155–167

Cummins RC (1990) Job stress and the buffering effect of supervisory support. Group Organ Manag 15(1):92–104

Dabos GE, Rousseau DM (2004) Mutuality and reciprocity in the psychological contracts of employees and employers. J Appl Psychol 89(1):52–72

Dalton D, Radtke RR (2012) The joint effects of Machiavellianism and ethical environment on whistle-blowing. J Bus Ethics 117(1):153–172

Eagle BW, Miles EW, Icenogle ML (1997) Interrole conflicts and the permeability of work and family domains: are there gender differences? J Vocat Behav 50(2):168–184

Edwards MR, Peccei R (2010) Perceived organizational support, organizational identification, and employee outcomes: testing a simultaneous multifoci model. J Personal Psychol 9:17–26

Eisenberger R, Stinglhamber F (2011) Perceived organizational support: fostering enthusiastic and productive employees. American Psychological Association, Washington

Eisenberger et al (1986) Perceived organizational support. J Appl Psychol 71(3):500–507

Erera IP (1992) Social support under conditions of organizational ambiguity. Hum Relat 45(3):247–264

Fakih A (2014) Availability of family–friendly work practices and implicit wage costs: new evidence from Canada. IZA Discussion Paper No. 8190

Feierabend A, Mahler P, Staffelbach B (2011) Are there spillover effects of a family supportive work environment on employees without childcare responsibilities? Manag Rev 22(2):188–209

Fernandez JP (1986) Child care and corporate productivity: resolving family work conflicts. Lexington Books, Lexington

Ford MT, Heinen BA, Langkamer KL (2007) Work and family satisfaction and conflict: a meta-analysis of cross-domain relations. J Appl Psychol 92(1):57–80

Forgas JP (1995) Mood and judgment: the affect infusion model (AIM). Psychol Bull 117(1):39–66

Forgas JP, Bower GH (1987) Mood effects on person perception judgements. J Pers Soc Psychol 53:53–60

Fornell C, Larcker D (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Market Res 18(1):39–50

Goff S, Mount M, Jamison R (1990) Employer-supported child care, work–family conflict, and absenteeism: a field study. Personal Psychol 43(4):793–809

Greenhaus JH, Beutell NJ (1985) Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Acad Manag Rev 10(1):76–88

Greenhaus JH, Parasuraman S (1986) A work-nonwork interactive perspective of stress and its consequences. J Organ Behav 8(2):37–60

Gross JJ, John OP (2003) Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes. Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J Personal Soc Psychol 85(2):348–362

Gutek BW, Searle S, Klepa L (1991) Rational versus gender role explanations for work–family conflict. J Appl Psychol 76(4):560–568

Halpern DF (2005) How time-flexible work policies can reduce stress, improve health, and save money. Stress Health 21(3):157–168

Hammer et al (2005) A longitudinal study of the effects of dual-earner couples’ utilization of family–friendly workplace supports on work and family outcomes. J Appl Psychol 4:799–810

Hammer et al (2009) Development and validation of a multidimensional measure of family supportive supervisor behaviors (FSSB). J Manag 35(4):837–856

Hammer et al (2011) Clarifying work–family intervention processes: the roles of work–family conflict and family-supportive supervisor behaviors. J Appl Psychol 96(1):134–150

Harman HH (1967) Modern factor analysis, 2nd edn. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

He et al (2014) Perceived organizational support and organizational identification: joint moderating effects of employee exchange ideology and employee investment. Int J Hum Res Manag 25(20):2772–2795

Heywood JS, Siebert WS, Wie X (2007) The implicit wage costs of family friendly work practices. Oxford Econ Pap N Ser 59(2):275–300

Hildenbrand K (2016) Help in finding the right balance: leadership, work–family balance and employee outcomes. In: PhD Thesis, Aston University, Birmingham

Hochschild AR (1997) The time bind: when work becomes home and home becomes work. Henry Holt and Company Inc, New York

Hofstede G (2001) Culture’s consequences: comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations, 2nd edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks

House JS (1981) Work stress and social support. Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA

Hunter LW, Thatcher SMB (2007) When do people produce? Effects of stress, commitment, and job experience on performance. Acad Manag J 50(4):953–968

Jahn EW, Thompson CA, Kopelman RE (2003) Rationale and construct validity evidence for a measure of perceived organizational family support (POFS): because purported practices may not reflect reality. Community, Work Fam 6(2):123–140

John OP, Gross JJ (2004) Healthy and unhealthy emotion regulation: personality processes, individual differences, and life span development. J Personal 72(6):1301–1334

Jorgensen et al (1996) Elevated blood pressure and personality: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull 120(2):293–320

Judge TA, Colquitt JA (2004) Organizational justice and stress: the mediating role of work–family conflict. J Appl Psychol 89(3):395–404

Kiewitz et al (2009) The interactive effects of psychological contract breach and organizational politics on perceived organizational support: evidence from two longitudinal studies. J Manag Stud 46:806–834

Kopelman RE, Greenhaus JH, Connolly TF (1983) A model of work, family, and inter role conflict: a construct validation study. Organ Behav Hum Perform 32(2):198–215

Kossek et al (2011) Workplace social support and work–family conflict: a meta-analysis clarifying the influence of general and work–family-specific supervisor and organizational support. Personal Psychol 64(2):289–313

Kottke JL, Sharafinski CE (1988) Measuring perceived supervisory and organizational support. Educ Psychol Meas 48(4):1075–1079

Kreiner GE, Ashforth BE (2004) Evidence toward an expanded model of organizational identification. J Organ Behav 25(1):1–27

Kurtessis et al (2015) Perceived organizational support: a meta-analytic evaluation of organizational support theory. J Manag 20(10):1–31

Lauber V, Storck J (2016) Helping with the kids? How family-friendly workplaces affect parental well-being and behavior. SOEP papers on multidisciplinary panel data research, No. 883

Lazarus RS (1991) Progress on a cognitive-motivational-relational theory of emotion. Am Psychol 46(8):819–834

Lazarus N (1999) Nationalism and cultural practice in the postcolonial world. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Lazarus RS, Folkman S (1984) Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer, New York

Lew DS, Bardoel AE (2017) The impact of national context and organizational policies: a cross-cultural analysis. In: Aycan Z, Ayman R, Korabik K (eds) The work–family interface in global context. Routeledge, New York, pp 51–99

Marique et al (2013) The relationship between perceived organizational support and affective commitment: a social identity perspective. Group Organ Manag 38(1):68–100

Matthews RA, Toumbeva TH (2015) Lagged effects of family-supportive organization perceptions and supervision in relation to generalized work-related resources. J Occup Health Psychol 20(3):301–313

McCarthy A, Darcy C, Grady G (2010) Work-life balance policy and practice: understanding line manager attitudes and behaviors. Hum Resour Manag Rev 20:8–167

McCarthy A, Cleveland JN, Hunter S, Darcy C, Grady G (2013) Employee work–life balance outcomes in Ireland: a multilevel investigation of supervisory support and perceived organizational support. Int J Hum Resour Manag 24(6):1257–1276

Meyer CS, Mukerjee S, Sestero A (2001) Work-life benefits: which ones maximize profits? J Manag Issues 13(1):28–44

Michel et al (2011) Antecedents of work–family conflict: a meta-analytic review. J Organ Behav 32(5):689–725

Moen P, Yu Y (2000) Effective work/life strategies: working couples, work conditions, gender, and life quality. Soc Probl 47(3):291–326

Morrison EW, Robinson SL (1997) When employees feel betrayed: a model of how psychological contract violation develops. Acad Manag Rev 22(1):226–256

Morrow PC (2011) Managing organizational commitment: insights from longitudinal research. J Vocat Behav 79(1):18–35

Nelson DL, Quick JC (1991) Social support and newcomer adjustment in organizations: attachment theory at work? J Organ Behav 12(6):543–554

Neves P, Eisenberger R (2014) Perceived organizational support and risk taking. J Manage Psycho 29(2):187–205

O’Driscoll et al (2003) Family-responsive interventions, perceived organizational and supervisor support, work–family conflict, and psychological strain. Int J Stress Manag 10(4):326–344

Ochsner KN, Gross JJ (2005) The cognitive control of emotion. Trends Cognit Sci 9(5):242–249

Ortony A (1988) Are emotion metaphors conceptual or lexical? Cognit Emot 2(2):95–104

Ozdasli K, Aytar O (2013) The effect of cultural infrastructure in business management: comparison of Turkish and Japanese Business Cultures. Int J Contempl Res Bus 4(12):434–444

Parasuraman S, Greenhaus JH, Granrose CS (1992) Role stressors, social support, and well-being among two-career couples. J Organ Behav 13(4):339–356

Perry-Smith JE, Blum TC (2000) Work–family human resource bundles and perceived organizational performance. Acad Manag J 43(6):1107–1117

Podsakoff P, MacKenzie S, Podsakoff N (2012) Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu Rev of Psychol 63:539–569

Pratt MG (1998) To be or not to be: central questions in organizational identification. In: Whetten DA, Godfrey PC (eds) Identity in organizations: building theory through conversations. Sage, Thousand Oaks, pp 171–207

Premeaux SF, Adkins CL, Mossholder KW (2007) Balancing work and family: a field study of multi-dimensional, multi-role work–family conflict. J Organ Behav 28(6):705–727

Rafaeli A, Semmer N, Tschan F (2009) Emotion in work settings. In: Sanders D, Scherer K (eds) Oxford companion to the affective sciences. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 414–416

Rafcanin Y, Heras ML, Bakker AB (2017) Family supportive supervisor behaviors and organizational culture: effects on work engagement and performance. J Occup Health Psychol 22(2):207–217

Raja U, Johns G, Ntalianis F (2004) The impact of personality on psychological contracts. Acad Manag J 47(3):350–367

Ramus CA, Steger U (2000) The roles of supervisory support behaviors and environmental policy in employee “Ecoinitiatives” at leading-edge European companies. Acad Manag J 43:605–626

Restubog et al (2008) Effects of psychological contract breach on organizational citizenship behavior: insights from the group value model. J Manag Stud 45(8):1377–1400

Riketta M, Van Dick R (2005) Foci of attachment in organizations: a meta-analytic comparison of the strength and correlates of workgroup versus organizational identification and commitment. J Vocat Behav 67(3):490–510

Riva E (2013) Workplace work–family interventions: italy in times of welfare state retrenchment and recession. Int J Sociol Soc Policy 33(9/10):565–578

Robinson SL, Morrison EW (2000) The development of psychological contract breach and violation: a longitudinal study. J Organ Behav 21(5):526–546

Robinson SL, Kraatz MS, Rousseau DM (1994) Changing obligations and the psychological contract: a longitudinal study. Acad Manag J 37(1):137–152

Rottenberg J, Gross JJ (2003) When emotion goes wrong: realizing the promise of affective science. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 10(2):227–232

Rousseau DM (1989) Psychological and implied contracts in organizations. Employ responsib rights J 2(2):121–139

Russo JA, Waters LE (2006) Workaholic worker type differences in work–family conflict. Career Dev Int 11(5):418–439

Russo M, Buonocore F, Carmeli A, Guo L (2015) When family supportive supervisors meet employees’ need for caring: implications for work–family enrichment and thriving. J Manag. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315618013 (Online First)