Abstract

Background

International doctors make up nearly half of the physicians working in Ireland and are an integral part of the health service. The COVID-19 pandemic declared in March 2020 led to a global healthcare emergency. Resulting national lockdowns precluded travel at a time of need for family support.

Aim

We aimed to measure the professional, psychosocial, and financial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on non-EEA doctors working in Ireland.

Methods

An 88-item online survey of demographics, well-being, and financial resilience was circulated nationally between November 2021 and January 2022. The results were analysed using RStudio and Microsoft Excel 365.

Results

One hundred thirty-eight responses were received. Sixty-two percent of responders reported wishing to stay in Ireland long-term and 44% had applied for citizenship. Despite 80% of responders working in their desired speciality, only 36% were on a specialist training scheme. Forty-seven percent felt their career was affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Seventy-three percent of respondents reported missing significant events in their home country. Over 50% reported significant mental health issues personally or in their families; however, only a minority sought professional help. Financial issues were a source of anxiety for 15% of respondents. Financial resilience was poor, 20% of respondents cited a 1-month financial reserve, 10% had a personal pension, and 9% had made a will.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a multifactorial negative impact on non-national doctors working in Ireland. More must be done to offer multidimensional support to this cohort who are a crucial part of the underserviced Irish healthcare system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) pandemic has had a negative impact on the physical and emotional well-being of healthcare workers worldwide. This has resulted in an increase in psychological distress in frontline doctors [1, 2]. The physical and emotional impact of working in a high-stress, understaffed environment was exacerbated by the onslaught of difficult decision-making, loss of patients and colleagues, and concern around infection risk [3]. For non-national doctors living and working abroad, the pandemic amplified pre-existing difficulties in living and working at great distances from family, friends, and other support groups.

Ireland has the highest proportion of internationally trained doctors working in any country in the European Union (EU), with over 42% non-European Economic Area (EEA) national doctors [4, 5]. Non-national doctors in Ireland face unique challenges and have difficulty accessing training posts and receiving long-term or permanent contracts. Despite making up nearly half of the physician workforce in Ireland, non-EEA doctors report finding it difficult to voice their concerns, with fears that speaking up can impact their reputation and job security, and likely make up a significant proportion of the 62.9% of doctors in training who report they do not feel their families would be cared for in Ireland in the event of their death [6, 7]. Despite these obstacles and added stressors, non-EEA doctors were crucial frontline workers in Ireland during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Aims

We aim to quantify the sacrifices made by international doctors by assessing the impact that the COVID-19 pandemic has had on non-national doctors, with a particular focus on career trajectory, physical and mental well-being, illness and death in family, travel, and financial resilience.

Methods

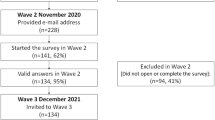

We conducted a qualitative study of non-EEA national doctors living and working in Ireland during the COVID-19 pandemic. An 88-item survey was distributed online using Google Forms and was open for completion between 29 November 2021 and 25 January 2022 during the 5th wave of the pandemic. The survey was circulated nationally by hospital e-mail lists, WhatsApp groups, and using social media. Ethical approval was granted through University College Cork. The results were analysed using RStudio (R version 3.5.2 Eggshell Igloo) and Microsoft Excel 365 (Version 2109).

Results

Demographics

One hundred thirty-eight people responded to the survey. The exact number of recipients who received the survey was not recorded; however, every effort was made to circulate the survey as widely as possible. Of 21,680 doctors registered with the Medical Council in 2021, 21.6% were international medical graduates [8]. Of the respondents, 59% were male, 39% were female, and 1% identified as non-binary, with 127 between 25 and 44 years of age. Thirty-five different nationalities were represented (Table 1). The majority of respondents surveyed were living in Leinster and Munster, in keeping with the population distribution of Ireland. Of those who completed the survey, 69% were married, 57% had children, 39% had a partner in full-time employment, and 7% had a partner in part-time employment.

At the time of completion, 40% of respondents had applied for citizenship through naturalisation and 4% had applied for citizenship through marriage. Of these applications, 38% were successful, with 57% still pending an outcome, and 3% reported an unsuccessful application.

Future plans

Sixty-two percent of respondents reported wishing to stay in Ireland long-term, 7% felt unsure about their plans, and 5% reported this decision as being career dependent. The reasons for this were varied, but no respondents reported this had to do with the practice in their home country. Of the 86 doctors wishing to remain in Ireland, the stated reasons included quality of life (43%), family reasons (19%), and the fact that Ireland felt like home (13%) (Fig. 1). Only 17% gave career progression as the primary factor.

Ireland is my home. I have friends and family here and consider this the place where I will live permanently. I studied here and have done all my medical training here. I hope to work in Ireland as a consultant to give back to my community.

Of the 35 respondents who did not wish to remain in Ireland long-term, 54% cited career progression as the main reason for not wanting to stay.

If I get trained and got specialist registration then yes, I will stay permanently but if it is not the case then obviously I have to leave at some stage.

We don’t get career progression in Ireland as non-national doctors. For example, in my case I have worked in Ireland for 7 years, CSTEM (Core Specialist Training in Emergency Medicine), not able to get into Emergency Medical higher specialist training. Tried GP- not even shortlisted. 4 years of emergency medicine experience (4 different hospitals), paediatrics, general medicine, anaesthetic experience, and orthopaedic experiences. Have got membership exam.

Medical training

Respondents completed their medical training in many different countries (Fig. 2), but with a strong majority coming from Pakistan (32%) and Ireland (30%). After qualifying, 30% of respondents completed an intern year in Ireland. Many respondents had experience at a variety of levels before arriving in Ireland, including 9% as a consultant and 17% as a registrar; 24% reported having completed speciality training.

When asked about current roles, 80% of respondents reported working in their desired speciality; however, only 36% were on a specialist training scheme. Of these, nineteen people reported being on basic specialist training schemes in either general internal medicine, general surgery, emergency medicine, or obstetrics and gynaecology. Eight respondents were on the GP training scheme. Twenty respondents (14%) reported being on higher specialist training schemes across a variety of specialities including histopathology (2%), geriatrics (1%), emergency medicine (1%), respiratory medicine (1%), obstetrics and gynaecology (2%), medical oncology (2%), rheumatology (1%), paediatrics (1%), ENT (1%), maternal medicine (1%), and cardiothoracic surgery (1%).

Impact of pandemic

Forty-seven percent of respondents reported their career plans were affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Looking outside of work, 26% reported a family illness during the pandemic (42% of which were COVID-19 related) and 9% reported a death in the family in Ireland (17% of which were from COVID-19 infection). Furthermore, 62% reported illness in a family member in their home country (61% of which from COVID-19 infection), with 57% of responders having experienced a death in the family in their home country (54% of which were from COVID-19 infection). There was a significant effect on the mental health of both doctors and their families (Figs. 3 and 4). Of concern is that only 12% and 22% actively sought help for either themselves or their families, respectively.

Irish COVID-19 measures prevented 64% of respondents from seeing sick or dying friends or family in their home country. Additionally, 73% of respondents report missing significant events in their home country including births, deaths, funerals, weddings, and holidays. Overall, the impact of travel had a major impact on non-national doctors (Figs. 5 and 6).

Financial issues

The mean household gross income in Ireland in 2021 was €75,847, giving a gross monthly figure of €6321 [9]. This is significantly more than the gross monthly earnings for over 70% of non-EEA doctors sampled (Fig. 7). Indeed, in a profession traditionally regarded as well-remunerated, 63% report being unable to survive for longer than 3 months in the event of a loss of income, with 20% citing 1 month as the upper limit (Fig. 8).

In terms of provisioning for the future, 90% of foreign doctors do not have a personal pension and 91% do not possess a will; just over half do not save money regularly, with 55% of doctors having less than €5000 in savings. It is also striking that while 61% of non-EEA doctors report being the household’s sole earner, 49% are also supporting an extended family. Consequently, 80% of the sample report worrying about money more than once a month, with 15% for whom financial issues are a daily source of anxiety (Fig. 9). When asked to describe, on a scale of 1 to 10, both how the household has coped with the pandemic and how resilient they would be to future shocks, 57% and 46% respectively rated their answers at 5 or less (Figs. 10 and 11).

In the context of long-standing intimations that the non-consultant hospital doctors (NCHDs) represented by the Irish Medical Organisation (IMO) have been considering strike action, a matter brought to a head at the recent annual general meeting (AGM) (21/05/22), it is also instructive to note that, in tandem with financial constraints, many junior doctors experience significant amounts of time poverty. On a Likert scale from 1 to 10, with 10 representing maximum distress, 58% of the sample chose a value of 6 or above in agreeing with the statement, ‘[m]y finances are a constraint in doing the things I enjoy, and getting the things I want, in my life’. Indeed, 41% have fallen behind with a bill at least once, with 8% reporting falling behind on more than 5 occasions. Eighty-five percent chose a value of 6 or above in an analogous statement concerning time: ‘My time is a constraint in doing the things I enjoy, and getting the things I want, in my life’ (Figs. 12 and 13). These attitudes have been exacerbated by the pandemic and such responses reflect the sentiments of many NCHDs. In a ballot of IMO members in May 2022, 97% of voters were in favour of industrial action, including strike action, which at the time of writing, appears imminent [10].

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a well-documented negative impact on healthcare workers worldwide [11]. Psychological distress has a detrimental impact on healthcare workers and leads to increased absenteeism, higher rates of physical and mental illness, and impaired performance at work [12]. Internationally, studies of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the medical workforce have reported that 40–50% of healthcare workers met the criteria for psychological distress and/or reported symptoms of depression or anxiety, with high levels of sleep disturbance and burnout [1, 12, 13], a result borne out by this study. In addition to formal mental health conditions, frontline physicians are at risk of moral injury, which is described as psychological distress that comes from one’s actions, or lack of actions, in a situation for which they are not adequately prepared [14]. While it is crucial to recognise and address these issues in all healthcare workers, it is vital to remember that, in any setting, foreign-born workers experience more psychosocial stress than native workers and have less access to professional support leading to decreased physical and mental well-being [15,16,17]; the experience of doctors working abroad during the pandemic is likely to be more negative than for physicians working in their own country.

Our study demonstrates the multi-faceted burden of the COVID-19 pandemic on non-national doctors working in Ireland (Fig. 14). Many non-EEA doctors experienced significant illness and/or death in the family during the pandemic, with over 60% reporting they missed an opportunity to see a sick or dying friend or relative in their home country. Despite this, 62% of survey participants state they wish to settle in Ireland permanently. However, this can be an arduous task, as this survey highlights the ‘very limited (training) opportunities for foreign doctors’, with 65% of respondents not on a specialist training scheme. As non-citizens, these frontline workers describe a sense of ‘loneliness’ and emphasise the difficulty in arranging visas to allow immediate family to visit as being ‘next to impossible’. Financial stress also impacts this cohort, and although half of the doctors are paid above the national median, many report difficulty meeting financial obligations. For non-national doctors who continue to work in Ireland despite these and other issues, this road ultimately leads to an ‘extremely difficult process of citizenship’. This is a crucial milestone for non-national doctors as the acquisition of Irish citizenship allows doctors to access specialist training posts, which provide better support and security and can ultimately lead to permanent consultant posts.

The experience of non-national doctors is not unique to those living and working away from home in Ireland. In the United States (US), this cohort of physicians are commonly referred to as foreign medical graduates (FMGs) or international medical graduates (IMGs), but by the US Code of Federal Regulation as ‘alien’, or non-US citizen, physicians. During the COVID-19 pandemic, alien physicians, who make up 24.5% of practising doctors in the US, were strongly recommended not to leave the country and were warned that re-entry would not be guaranteed by the Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG) [18, 19]. In contrast, the French government announced in September 2020 that healthcare workers who worked in France through the pandemic would be eligible for fast-tracked citizenship, explaining that foreign workers gave their time during the COVID-19 crisis and had earned something in return [20, 21]. By September 2021, French Junior Minister of Citizenship Marlène Schiappa announced the approval of 12,012 citizenship applications from frontline healthcare workers [22]. Although there has been no published research on the impact of this gesture on non-national physicians in France, it is well established that gestures of gratitude are associated with better psychological well-being [23, 24]. In the UK, frontline Pakistani emigrant physicians unanimously reported that the gratitude displayed through government support and campaigns, such as priority in shops, slogans thanking the National Health Service (NHS) staff, and the weekly ‘clap for the NHS’, had a positive impact on their experience through the pandemic [25].

The Irish health system has been acknowledged for using the COVID-19 pandemic to bring about health system change. Through policy amendments, the implication of long-awaited independent health identifiers (IHI), budget expansions, the creation of new contracts and hospital beds, and free COVID-19 infection-related care, the health system absorbed the shock of an unexpected pandemic and demonstrated the resilience of the Irish system [26]. These changes, while crucial, do not impact the frontline healthcare workers who carried out the day-to-day, hands-on care of people living in Ireland through the pandemic. The non-EEA doctors continue to face the same struggles, many of which are now exaggerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, despite their dedication to the Irish health service throughout a time when they lacked access to the physical and emotional support of being near friends and family. It is important to emphasise that the COVID-19 pandemic highlights pre-existing issues for non-citizen physicians. As one study participant explained:

Covid 19 simply amplifies issues already existing. Sometimes it seems like there are two parallel career pathways for nationals and non-nationals. It takes a non-national double the time to go through an alternative training program to get oneself up to consultant level. And the availability of consultant positions then is a separate matter. That prolongs financial issues and exacerbates anxiety. The system is untenable unless reformed and opened.

It is important that the remodelling of the Irish health system moves beyond bureaucracy and extends to policy change for non-national physicians who worked in Ireland during the COVID-19 pandemic. Better support is needed in all areas: psychological, social, financial, training, relocation, and access to structured training schemes. Applications of frontline healthcare workers for visas or naturalisation should be prioritised and fast-tracked. The residence rights of non-EEA nationals, and particularly their children and spouses, need to be improved. Spouses of non-EEA national doctors should be entitled to a visa which allows them to work to provide more financial stability to their families. Short-term visas should be accessible and processed efficiently to allow immediate family members of non-EEA doctors to visit their hardworking relatives in Ireland.

For non-national doctors who attended medical school in Ireland and chose to stay and work in the health system, they should be assessed on merit, just as their resident counterparts. Allocation of specialist training posts should be based on merit and experience, rather than solely on nationality. Consideration of ‘total life space’, including family life, children in school, underlying medical conditions, and other unique circumstances, should be considered to minimise disruption to everyday life for training doctors in Ireland [27]. Ultimately, a gesture such as the invitation for citizenship application, as in France, would be undoubtedly well received and potentially could result in more long-term, committed, speciality trained physicians in Ireland; this would also help to improve the ongoing doctor retention and consultant recruitment crisis.

Our study is not without limitations. The results have only captured the opinions of a small percentage of the population of non-EEA doctors working as doctors in Ireland. This study also focuses solely on non-EEA frontline doctors and does not address the experience of other frontline healthcare workers.

Summary

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted both our reliance on international doctors in Ireland and their inequitable treatment in the healthcare system in which they work. This study highlights the multi-layered impact of the pandemic on a group that plays a significant role in healthcare delivery in Ireland. These impacts range from financial to mental health, impacts that are compounded by pandemic enforced isolation from family at a time of global distress and illness and death in their home countries. This survey highlights their financial frailty and their role in providing financial support to family members at home. The dependence of the health system on this cohort contrasts with how they are treated. Despite their necessity, non-EEA doctors cannot access internship places, specialist training posts, long-term contracts, and consultant posts in the same fashion as their peers who are citizens or those with permission to reside in Ireland with a Stamp 4, usually obtained through an Irish spouse or civil partner. Most non-national doctors emigrate to Ireland to access training opportunities to facilitate career progression and will migrate elsewhere if they cannot access these opportunities [27].

References

Ali S, Maguire S, Marks E et al (2020) Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers at acute hospital settings in the South-East of Ireland: an observational cohort multicentre study. BMJ Open 10(12):e042930. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042930

Couarraze S, Delamarre L, Marhar F et al (2021) The major worldwide stress of healthcare professionals during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic — the international COVISTRESS survey. PLoS ONE 16(10):e0257840. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257840

Leo CG, Sabina S, Tumolo MR et al (2019) Burnout among healthcare workers in the COVID 19 era: a review of the existing literature. Front Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.750529

Chevillard G (2021) Training, migration and retention of doctors: is Ireland a Danaides’ Jar?; Comment on “Doctor retention: a cross-sectional study of how Ireland has been losing the battle.” Int J Health Policy Manag 10(10):658–659. https://doi.org/10.34172/ijhpm.2020.217

Humphries N, Creese J, Byrne J-P, Connell J (2021) COVID-19 and doctor emigration: the case of Ireland. Hum Resour Health 19(1):29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-021-00573-4

Kijowsjki F, Moore S, Iqbal S et al (2021) Financial resilience among doctors in training and the COVID-19 pandemic. Ir Med J 114(6)

Creese J, Byrne J-P, Matthews A et al (2021) “I feel I have no voice”: hospital doctors’ workplace silence in Ireland. J Health Organ Manag 35(9):178–194. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHOM-08-2020-0353

Medical Council (2021) Summary of the medical workforce intelligence report 2021. https://www.medicalcouncil.ie/news-and-publications/reports/medical-workforce-intelligence-report-2021.pdf

Central Statistics Office. SIA74 — annual income measures. 2022. https://data.cso.ie/SIA74

Irish Medical Organisation. NCHDs have voted “overwhelmingly” in favour of industrial action. 2022. https://www.imo.ie/news-media/news-press-releases/2022/nchds-have-voted-overwhel/index.xml

Cutler DM (2022) Challenges for the beleaguered health care workforce during COVID-19. JAMA Health Forum 3(1):e220143–e. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.0143

Roberts T, Daniels J, Hulme W et al (2021) Psychological distress during the acceleration phase of the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey of doctors practising in emergency medicine, anaesthesia and intensive care medicine in the UK and Ireland. Emerg Med J 38(6):450. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2020-210438

Ho CS, Chee CY, Ho RC (2020) Mental health strategies to combat the psychological impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) beyond paranoia and panic. Ann Acad Med Singap 49(3):155–160

Greenberg N, Docherty M, Gnanapragasam S, Wessely S (2020) Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ 368:m1211. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1211

Font A, Moncada S, Benavides FG (2012) The relationship between immigration and mental health: what is the role of workplace psychosocial factors. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 85(7):801–806. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-011-0724-6

Aalto A-M, Heponiemi T, Keskimäki I et al (2014) Employment, psychosocial work environment and well-being among migrant and native physicians in Finnish health care. Eur J Pub Health 24(3):445–451. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cku021

Doki S, Sasahara S, Matsuzaki I (2018) Stress of working abroad: a systematic review. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 91(7):767–784. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-018-1333-4

Al Awamlh BAH (2021) Alien J-1 Physicians in a pandemic. JAMA Intern Med 181(6):743–744. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.0730

Tiwari V, Bhardwaj A, Sonani B, Mehta AC (2020) Urgent issues facing immigrant physicians in the United States in the COVID-19 era. Ann Intern Med 173(10):838–839. https://doi.org/10.7326/m20-4103

Méheut C (2022) They helped France fight the virus. Now France is fast-tracking their citizenship. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/22/world/europe/france-naturalization-covid-frontline.html

l’Intérieur Md (2021) Reconnaissance de l’engagement des ressortissants étrangers pendant l’état d’urgence de la COVID-19. https://www.immigration.interieur.gouv.fr/fr/Integration-et-Acces-a-la-nationalite/La-nationalite-francaise/Reconnaissance-de-l-engagement-des-ressortissants-etrangers-pendant-l-etat-d-urgence-de-la-COVID-19

Taggart E (2021) France has given citizenship to 12,000 frontline workers — can Ireland do the same? TheJournal.ie

Komase Y, Watanabe K, Hori D et al (2021) Effects of gratitude intervention on mental health and well-being among workers: a systematic review. J Occup Health 63(1):e12290. https://doi.org/10.1002/1348-9585.12290

Schache K, Consedine N, Hofman P, Serlachius A (2019) Gratitude — more than just a platitude? The science behind gratitude and health. Br J Health Psychol 24(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12348

Saleem J, Ishaq M, Zakar R et al (2021) Experiences of frontline Pakistani emigrant physicians combating COVID-19 in the United Kingdom: a qualitative phenomenological analysis. BMC Health Serv Res 21(1):291. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06308-4

Burke S, Parker S, Fleming P et al (2021) Building health system resilience through policy development in response to COVID-19 in Ireland: from shock to reform. Lancet Reg Health Eur. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100223

Creese J, Byrne J-P, Conway E et al (2021) “We all really need to just take a breath”: composite narratives of hospital doctors’ well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18042051

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the University College Cork Social Research Ethics Committee and is compliant with ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from participants completing the survey.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Carroll, H.K., Moore, S., Farooq, A.R. et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on non-national doctors in Ireland. Ir J Med Sci 192, 2033–2040 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-022-03220-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-022-03220-6