Abstract

CT colonography has emerged as the investigation of choice for suspected colorectal cancer in patients when a colonoscopy in incomplete, is deemed high risk or is declined because of patient preference. Unlike a traditional colonoscopy, it frequently reveals extracolonic as well as colonic findings. Our study aimed to determine the prevalence, characteristics and potential significance of extracolonic findings on CT colonography within our own institution. A retrospective review was performed of 502 patients who underwent CT colonography in our institution between January 1, 2010 and January 4, 2015. Of 502 patients, 60.63% had at least one extracolonic finding. This was close to other similar-sized studies (Kumar et al. Radiology 236(2):519–526, 2005). However, our rate of E4 findings was significantly higher than that reported in larger studies at 5.3%(Pooler et al. AJR 206:313–318, 2016). The difference may be explained by our combination of symptomatic/screening patients or by the age and gender distribution of our population. Our study lends support to the hypothesis that CT colonography may be particularly useful in identifying clinically significant extracolonic findings in symptomatic patients. CT colonography may allow early identification of extracolonic malignancies and life-threatening conditions such as an abdominal aortic aneurysm at a preclinical stage when they are amenable to medical or surgical intervention. However, extracolonic findings may also result in unnecessary investigations for subsequently benign findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Colonoscopy is the first-line investigation for suspected colorectal cancer. For those patients in whom a colonoscopy is incomplete, is deemed high risk or is declined because of patient preference, CT colonography (CTC) is the next investigation of choice.

CT colonography has several advantages over a traditional colonoscopy. It allows a complete examination of the abdomen and pelvis. It is a relatively safe investigation that is well tolerated by most patients. It was accepted as a screening tool for colorectal cancer by the American Cancer Society in 2008. Importantly, it also raises the possibility of uncovering extracolonic findings which remain blind to endoscopic examination. Radiologists must report both colonic and extracolonic findings.

A systematic review by Xiong et al. found that 40% of patients undergoing CT colonography had at least one extracolonic finding. Fourteen percent of all patients had a “significant finding” requiring further investigation [1]. Pooler et al. looked at E4 (potentially significant) findings in a screening population and found that 2.5% had E4 findings [2].

The aim of our study was to determine the prevalence and characteristics of extracolonic findings from CT colonography within our own institution.

Methods

A retrospective analysis was conducted of all CT colonography studies performed in our institution from January 1, 2010 to January 4, 2015 using the picture archiving and communication system (PACS). All studies in this period were included in this analysis regardless of the underlying indication for the scan. The total number of patients who underwent CT colonography during the study period was 502. This comprised 350 females and 152 males with a mean age of 66.63 years.

Patients were administered 20 mg of intravenous hyoscine butylbromide before the scan. They were asked to position themselves in a lateral decubitus position, and a catheter tip was introduced to the rectum. The colon was insufflated with four litres of carbon dioxide to a pressure of 20–25 psi. A topogram was performed before the supine scan to ensure adequate colonic distension. Additional carbon dioxide was administered before the prone scan if tolerated by the patient. No intravenous contrast was administered.

Examinations were performed on a 64-slice Toshiba scanner using a slice collimation of 5 mm, a pitch of 0.8 and a kVp of 120. Images were networked to a workstation using customised software. All CTs were read by one of two consultant radiologists, each with over 10 years of professional experience.

The formal reports of these studies were examined, and any extracolonic findings were identified. These findings were classified according to the CT colonography reporting and data system [3] (C-RADS) as E0, E1, E2, E3 or E4 (Table 1).

Results

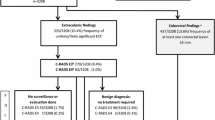

In total, 303 of 502 patients (60.36%) had at least one extracolonic finding. This included 27 patients (5.3%) who had an E4 finding (Table 2).

The most common benign (E2) findings were renal cyst (n = 54), gallbladder calculus (n = 38), hiatus hernia (n = 34), renal calculus (n = 25) and atherosclerotic aorta (n = 24) (Table 3 ). The most common benign but important (E3/4) findings were pulmonary nodule (n = 14), renal mass (n = 11), complex liver lesion (n = 7), lymphadenopathy (n = 4) and adrenal mass (n = 3). Three extracolonic malignancies were incidentally identified on CT colonography during the study period—a renal cell carcinoma (Fig. 1a, b), an ovarian carcinoma (Fig. 2a, b) and a lung carcinoid (Fig. 3), all of which were surgically resected.

Discussion

Our study aimed to determine the prevalence, characteristics and potential significance of extracolonic findings on CT colonography within our own institution and to compare our experience with that of other centres.

A retrospective review by Hara et al. first drew attention to extracolonic findings from CT colonography [4]. They found that 30 (11%) of 264 patients at high risk of colorectal cancer had highly important extracolonic findings. Pickhardt et al. found that extracolonic cancer exceeded colorectal cancer in a retrospective review of 10,286 patients in a CT colonography screening population [5]. However, a 2009 commentary predicted a “deluge” of incidental findings from CT colonographies which would drive up costs, anxiety, morbidity and mortality [6].

The major advantage of CT colonography is the early identification of extracolonic malignancies and life-threatening conditions such as an abdominal aortic aneurysm at a preclinical stage when they are still amenable to medical or surgical intervention. It is a relatively safe investigation which is well tolerated by the majority of patients.

One disadvantage of CT colonography is radiation exposure in a situation where the alternative (optical colonoscopy) is radiation-free. Modern CT scanners with a low-dosage protocol can keep doses under 5 mSv. However, an increased risk of malignancy seems likely, particularly for older patients and those undergoing multiple scans [7]. There is significant expense associated with further investigations. One study found that the mean cost of working up unexpected findings from CT colonography was approximately equal to the cost of the CT colonography itself [8]. Halligan et al. found that the average cost per patient of working up extracolonic findings was £99 v £5 for CT colonography v barium enema, and £153 v £0 for CT colonography v colonoscopy [9].

In addition, extracolonic findings may result in “unnecessary” investigations for subsequently benign findings. However, Plumb et al. used a discreet choice experiment in a CT colonography screening population to establish that both patients and healthcare professionals believe that the diagnosis of an extracolonic malignancy from a screening CT colonography outweighs the potential disadvantages of further imaging and invasive investigations brought about by false positive results. For patients, the median tipping point was 99.8% for radiological follow-up and 10% for invasive follow-up. The median tipping point for healthcare professionals was 40% for radiological follow-up and 5% for invasive follow-up. It appears that the specificity of a CT colonography in a screening population is likely to be highly acceptable to both patients and doctors [10].

The reported incidence of extracolonic findings in the literature is variable. The overall incidence in our study was 60.63%. This was close to other similar-sized studies [11]. Smaller studies have reported lower incidences. The incidence was 41% in a study by Hara et al. [4] and 15% in a study by Edwards et al. [12]. However, our rate of E4 findings was significantly higher than that reported in the largest study of 7952 screening patients [2].

It was suggested that this may be due to our own combination of symptomatic and screening patients. However, a recent 2019 study of 388 patients found no statistically significant difference in E scores or clinical outcomes of extracolonic findings between symptomatic and screening patients [20]. It is likely that other factors such as the age and gender distribution of our population are at play.

An increased incidence of extracolonic findings from CT colonography is associated with the use of intravenous contrast [13], high-dosage radiation protocols [14], increasing age [15] and female gender [16]. In particular, the predominance of females in our study most likely explains the high number of E3/E4 findings, since other studies have found that up to 25% of E3 findings are adnexal or uterine lesions [21].

Symptomatic patients with a colonic finding are less likely to have an extracolonic finding, while symptomatic patients without a colonic finding are more likely to have an extracolonic finding investigated [16]. In symptomatic patients, it is thought that up to 10% of extracolonic findings may account for the patient’s symptoms from their initial presentation [17].

The CT colonography reporting and data system establishes a standard approach to the reporting of colonic and extracolonic findings and acts as a guide to management by estimating the clinical significance of these findings. A study of 2277 screening patients found that 46% had at least one extracolonic finding, but only 11% were E3/4 [19]. A study of symptomatic patients found double the rate of E3/4 findings [9]. Our own study population was a combination of screening and symptomatic patients, and the rate of E3/4 findings was 18%. This lends support to the conclusion that CT colonography may be particularly useful in symptomatic patients.

Our study identified three extracolonic malignancies from 502 patients. It could be hypothesised that CT colonography accelerated these diagnoses. One prospective, randomised trial of patients with symptoms of colorectal cancer found that extracolonic cancer was indeed diagnosed at twice the expected rate for the general population at 1 year post randomisation to CT colonography, but time to diagnosis was not reduced compared with patients who underwent a barium enema or colonoscopy [9]. This would suggest that patients who underwent a barium enema or colonoscopy as their initial investigation may have undergone further abdominopelvic imaging as a result of persistent abdominal symptoms not explained by the initial test, ultimately leading to a diagnosis of extracolonic cancer in a similar timeframe to patients who had a CT colonography up front.

It has been suggested that radiographers may have a role in identifying extracolonic findings at the time of the scan and performing further same-day imaging if and when required. However, a Dutch study in 2012 invited eight radiographers to engage in a structured training programme, to triage cases based on the CT colonography reporting and data system and to flag the appropriate scans for a radiologist review. They found that correct identification of E3 findings improved from 52 to 70% after training, but identification of E4 findings was unchanged at 69% [18]. As such, radiographers should not be expected to identify all extracolonic findings.

Our study was limited to a single centre. The CT colonography reporting and data system was designed for screening rather than symptomatic investigations, and the absence of a comprehensive classification table means that the E score given is dependent on the subjective opinion of the reporting radiologist. Two radiologists report CT colonography studies in our institution, and their personal thresholds for reporting extracolonic findings may vary, particularly for those that are perceived to be low risk.

The National Bowel Screening Programme, Bowel Screen, was rolled out in 2012. While CT colonography studies have largely been deferred in our institution since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, they have recently been restarted on a regular basis. The resultant backlog is likely to result in greater pressure on CT colonography services at a local and national level.

In summary, our study aimed to assess the prevalence, characteristics and potential significance of extracolonic findings on CT colonography within our own institution. We found a similar rate of extracolonic findings to other similar-sized studies [11] but a higher rate of E4 findings than larger studies [2]. Our study lends support to the hypothesis that CT colonography may be particularly useful in identifying clinically significant extracolonic findings in symptomatic patients, and this will bring both opportunities and challenges in the years ahead.

Change history

30 May 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-022-03033-7

References

Xiong T, Richardson M, Woodroffe R et al (2005) Incidental lesions found on CT colonography: their nature and frequency. Br J Radiol 78(925):22–29

Pooler BD, Kim DH, Pickhardt PJ (2016) Potentially important extracolonic findings at screening CT colonography: incidence and outcomes data from a clinical screening program. AJR 206:313–318

Zalis ME, Barish MA, Choi JR et al (2005) CT colonography reporting and data system: a consensus proposal. Radiology 236(1):3–9

Hara AK, Johnson CD, MacCarty RL, Welch TJ (2000) Incidental extracolonic findings at CT colonography. Radiology 215:353–357

Pickhardt PJ, Kim DH, Meiners RJ et al (2010) Colorectal and extracolonic cancers detected at screening CT colonography in 10,286 asymptomatic adults. Radiology 255:83–88

Berland LL (2009) Incidental extracolonic findings on CT colonography: the impending deluge and its implications. J Am Coll Radiol 6:14–20

Albert JM (2013) Radiation risk from CT: implications for cancer screening. Am J Roentgenol 201:W81–W87.AT

Xiong T, McEvoy K, Morton DG et al (2006) Resources and costs associated with incidental extracolonic findings from CT colonography: a study in a symptomatic population. Br J Radiol 79:948–961

Halligan S, Wooldrage K, Dadswell E et al (2015) SIGGAR investigators, Identification of extra-colonic pathologies by computed tomographic colonography in symptomatic patients. Gastroenterology. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2015.03.011

Plumb AA, Boone D, Fitzke H et al (2014) Detection of extracolonic pathologic findings with CT colonography: a discrete choice experiment of perceived benefits versus harms. Radiology 273:144–152

Yee J, Kumar NN, Godara S et al (2005) Extracolonic abnormalities discovered incidentally at CT colonography in a male population. Radiology 236(2):519–526

Edwards JT, Wood CJ, Mendelson RM, Forbes GM (2001) Extracolonic findings at virtual colonoscopy: implications for screening programs. Am J Gastroenterol 96:3009–3012

Spreng A, Netzer P, Mattich J et al (2005) Importance of extracolonic findings at IV contrast medium-enhanced CT colonography versus those at non-enhanced CT colonography. Eur Radiol 15:2088–2095

van Gelder RE, Venema HW, Serlie IW et al (2002) CT colonography at different radiation dose levels: feasibility of dose reduction. Radiology 224:25–33

Park SK, Park DI, Lee SY et al (2009) Extracolonic findings of computed tomographic colonography in Koreans. World J Gastroenterol 15:1487–1492

Khan KY, Xiong T, McCafferty I et al (2007) Frequency and impact of extracolonic findings detected at computed tomographic colonography in a symptomatic population. Br J Surg 94:355–361

Ng CS, Doyle TC, Courtney HM et al (2004) Extracolonic findings in patients undergoing abdomino-pelvic CT for suspected colorectal carcinoma in the frail and disabled patient. Clin Radiol 59:421–430

Boellaard TN, Nio CY, Bossuyt PMM et al (2012) Can radiographers be trained to triage CT colonography for extracolonic findings? Eur Radiol 22(12):2780–2789

Veerappan GR, Ally MR, Choi JH et al (2010) Extracolonic findings on CT colonography increases yield of colorectal cancer screening. AJR Am J Roentgenol 195:677–686

Taya M, McHargue C, Ricci ZJ et al (2019) Comparison of extracolonic findings and clinical outcomes in a screening and diagnostic CT colonography population. Abdom Radiol (NY) 44(2):429–437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-018-1753-3

Pooler BD, Kim DH, Pickhardt PJ (2016) Indeterminate but likely unimportant extracolonic findings at screening CT colonography (C-RADS Category E3): incidence and outcomes data from a clinical screening program. AJR Am J Roentgenol 207(5):996–1001. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.16.16275

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

The original online version of this article was revised: The original online version of this article was revised due to a retrospective Open Access cancellation.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lambe, G., Hughes, P., Rice, L. et al. The bowel and beyond: extracolonic findings from CT colonography. Ir J Med Sci 191, 909–914 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-021-02595-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-021-02595-2