Abstract

Background

Burnout constitutes a significant problem among physicians which impacts negatively upon both the doctor and their patients. Previous research has indicated that burnout is prevalent among primary care physicians in other European countries and North America. However, there is a paucity of research assessing burnout among Irish general practitioners and examining predictive factors.

Aims

To report the findings of a survey of burnout among Irish general practitioners, and assess variables related to burnout in this population.

Methods

An online, anonymous questionnaire was distributed to general practitioners working in the Republic of Ireland.

Results

In total, 683 general practitioners (27.3 % of practising Irish general practitioners) completed the survey. Of these, 52.7 % reported high levels of emotional exhaustion, 31.6 % scored high on depersonalisation and 16.3 % presented with low levels of personal accomplishment. In total, 6.6 % presented with all three symptoms, fulfilling the criteria for burnout. Emotional exhaustion was higher among this sample than that reported in European and UK studies of burnout in general practitioners. Personal accomplishment was, however, higher in this sample than in other studies. Multiple regression analyses revealed that younger age, non-principal status role, and male gender were related to increased risk of burnout symptoms.

Conclusions

The symptoms of burnout appear prevalent among Irish general practitioners. This is likely to have a detrimental impact both upon the individual general practitioners and the patients that they serve. Research investigating the factors contributing to burnout in this population, and evaluating interventions to improve general practitioner well-being, is, therefore, essential.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Burnout is a psychological syndrome resulting from chronic work-related stress that is characterised by high levels of emotional exhaustion, or chronic feelings of emotional and physical strain, high levels of depersonalisation, manifested as feelings of detachment from, and unempathetic attitudes towards, others such as patients, and low personal accomplishment, or poor feelings of self-efficacy [1]. Burnout has been shown to impact negatively on job performance (i.e., absenteeism, intention to change job, turnover, productivity and effectiveness), mental health, and physical health [1, 2].

Medical doctors appear particularly vulnerable to experiencing burnout. A US-based research study found that doctors were significantly more likely to experience symptoms of burnout and job dissatisfaction than any other professional group [3]. Studies of burnout prevalence among physicians have led researchers to estimate that, at any given time, one in three doctors is experiencing burnout [4]. However, levels of burnout have been shown to vary between medical specialties.

General practitioners have been found to have a higher incidence of burnout than doctors in other specialities such as cancer physicians, surgeons, paediatricians, pathologists and psychiatrists [3, 5]. A research study [6] examining the prevalence of burnout symptoms across 1393 primary care physicians in 12 European countries found that 43 % of respondents scored high on emotional exhaustion, 35 % scored high on depersonalisation, and 32 % scored low on personal accomplishment. Among general practitioners, identified predictors of burnout include factors such as older age [6–8], gender [6, 7], perceived poor opportunities for continuing medical education [5, 7], increased workload [5], and public type of employment [5].

High levels of burnout have negative implications for both doctors and their patients. For doctors, burnout has been linked to elevated rates of depression and suicide [9, 10]; reduced quality of life [10]; increased absenteeism and turnover [11]; and increased smoking, alcohol consumption and psychotropic medication usage [6]. Furthermore, burnout has been shown to negatively impact upon patient safety and quality of care. Burnout has been linked to a reduced quality of, or suboptimal, patient care [12, 13]; increased medical errors [10, 13]; poorer patient outcomes including longer recovery times and reduced patient satisfaction [14]; reduced empathy for patients [15]; poorer interactions with patients [16]; and unprofessional conduct [17].

Although burnout has been investigated extensively internationally, this research has tended to focus on hospital-based doctors. There is also a paucity of research assessing burnout among Irish physicians. The aims of the current study were:

-

To identify the prevalence of burnout among a sample of Irish general practitioners;

-

To identify whether there are differences in levels of burnout based on specific predictor variables that have been shown to moderate levels of burnout in other studies (age, gender, seniority, and practice setting); and

-

To compare the levels of burnout observed among our sample of Irish general practitioners with levels of burnout found in general practitioner populations in the UK [18], mainland Europe [6], and North America [19].

Method

Procedure

Ethical approval was granted by the Research Ethics Committee of the Irish College of General Practitioners. Following this, an online, anonymous questionnaire was distributed to general practitioners through Gorillasurvey™, a primary care survey provider with 1145 registered Irish clinicians. Gorillasurvey™ requires individuals to have an Irish Medical Council registration number to take part in surveys, thereby preventing multiple or inappropriate responses. Participants were entered into a prize draw upon completion of the questionnaire.

Instrument

The questionnaire consisted of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS) [20] accompanied by items seeking demographic information (i.e., gender, age, practice type, seniority). The MBI-HSS is a 22-item measure of burnout intended for use with individuals working in human services that has been demonstrated to have acceptable psychometric properties [1]. The survey consists of three subscales: Emotional Exhaustion (nine items), Depersonalisation (eight items), and Personal Accomplishment (five items). Participants indicate the frequency with which they have certain feelings about their work using a seven-point rating scale which ranges from 0 (never) to 6 (every day). Norms and cut-off scores are available [20] for each of the subscales so that participants can be classified as scoring low, average, or high on each dimension. Burnout is considered to be present when an individual presents with high levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation in combination with low levels of personal accomplishment [20].

Data analysis

Initially, subscale scores were calculated to determine means and standard deviations of scores on each subscale and to identify the number of participants scoring “high” on each of the subscales or meeting the criteria for burnout. Next, a series of three regressions were conducted to examine whether demographic variables were predictive of burnout symptoms among our sample. These multiple regressions were carried out with gender (male, female), practice (rural, mixed, urban), seniority/role (principal, assistant, general practitioner trainee, locum), and age (<40, 41–55, 56–70) as the dependent variables. Emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation and personal accomplishment were each used in turn as the criterion variable.

Results

Participants

A total of 683 general practitioners responded to the questionnaire (representing 68 % of the Gorillasurvey™ panel and 27.3 % of practising Irish general practitioners [21]). Of these respondents, 343 were male (50.2 %) and 340 were female (49.8 %). The majority of respondents were aged between 41 and 55 years (n = 263; 38.5 %), followed by those aged under 40 years (n = 261; 38.2 %), and those aged between 56 and 70 years (n = 159; 23.3 %). Participants were primarily the principal general practitioner in their practice (n = 457; 66.9 %) or an assistant general practitioner (n = 146; 21.4 %), although trainee general practitioners (n = 51; 7.5 %) and locum general practitioners (n = 29; 4.2 %) also participated. Most participants worked in practices based in urban settings (n = 278; 40.7 %), 141 participants (20.6 %) worked in a rural setting and 264 participants (38.7 %) were based in a mixed setting.

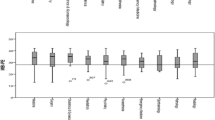

Participants’ mean score on the emotional exhaustion subscale was 28.0 (SD = 12.4; range = 0–54), 9.7 (SD = 6.7; range = 0–30) on the depersonalisation subscale, and 38.0 (SD = 6.3; range = 1848) on the personal accomplishment subscale. Examining these responses in more detail revealed that 360 participants (52.7 %) were experiencing high levels of emotional exhaustion, 216 participants (31.6 %) reported high levels of depersonalisation, and 111 participants (16.3 % reported) reported low levels of personal accomplishment. In total, 45 participants (6.6 %) met the criteria for burnout (i.e., high emotional exhaustion, high depersonalisation, and low personal accomplishment). A comparison between our sample’s scores on the MBI-HSS and those reported by previous studies of general practitioners in the UK [18], Europe [6], and North America [19] is presented in Table 1.

The four-predictor multiple regression model (i.e., gender, practice setting, seniority/role, and age) was found to account for 4.5 % of the variance in the emotional exhaustion score [F(8,674) = 3.98, p < .001]. As can be seen in Table 2, the emotional exhaustion score for assistant general practitioners and trainees was significantly lower than that for principal general practitioners. Also, general practitioners aged 56–70 years had significantly lower emotional exhaustion scores than those aged less than 40. When controlling for the other variables, neither gender nor practice location was found to have an impact on emotional exhaustion.

The four-predictor model was found to account for 3.7 % of the variance in the depersonalisation score [F(8,674) = 3.28, p < .001]. As can be seen from Table 3, male general practitioners had significantly higher depersonalisation scores than female general practitioners. General practitioners aged under the age of 40 years had significantly higher depersonalisation scores than general practitioners over 70 years.

The four-predictor model did not explain a significant proportion of the variance in personal accomplishment (F(8,674) = .63, n.s.), nor were any of the individual predictor variables significant for personal accomplishment.

Discussion

The primary aim of the current study was to examine the prevalence of burnout in a sample of Irish general practitioners. Our results suggest that the symptoms of burnout are relatively common in this population, with over half of the sample reporting a high level of emotional exhaustion and almost a third reporting a high level of depersonalisation. However, a smaller proportion of the Irish general practitioners reported low feelings of professional competence or personal accomplishment than has been found in other studies conducted in the UK and Europe [6, 18, 19]. Predictors of burnout symptoms identified included younger age, non-principal status, and male gender, and may offer guidance for conducting interventions to improve the well-being of general practitioners.

The comparison of our findings with the results from studies of burnout among UK [18], European [6], and North American [19] general practitioners revealed that Irish doctors appeared to experience comparatively higher levels of emotional exhaustion, marginally lesser depersonalisation, and greater feelings of personal accomplishment than their international counterparts. This is perhaps surprising as it might be anticipated that the higher levels of emotional exhaustion would be associated with higher depersonalisation and lower personal accomplishment. It appears that, in spite of high stress and emotional exhaustion, Irish general practitioners are still able to derive satisfaction from their work and to feel efficacious, and that patients are less likely to receive substandard care [18].

These findings also raise questions regarding the levels of resilience among Irish general practitioners who may have shielded them from the detrimental effects of work stress on interactions with, or perceptions of, patients and feelings of personal efficacy. Research conducted among physicians [22] has implicated a number of factors in resilience such as feelings of satisfactions associated with work (e.g., gratification resulting from patient interactions or medical efficacy), engagement in specific protective practices (e.g., leisure time, contact with colleagues, time with family and friends, personal reflection, setting of boundaries, limitation of working hours, etc.), and specific attitudes (e.g., acceptance and realism, appreciating the positive things).

It is possible that the education or training of Irish general practitioners has promoted greater resilience in this population. However, it is more likely that contextual factors associated with working in general practice in the different countries differ and that these contribute to the greater feelings of personal accomplishment and lower feelings of depersonalisation observed in our sample. Factors predictive of burnout that may vary from country to country include opportunities for continuing medical education [5, 7], workload [5], and type of employment (i.e., public or private) [5] and impact upon the experience of burnout symptoms in this way. For example, prior research has suggested that working in a public practice is associated with lower personal accomplishment [5]. As Irish general practitioners typically work in mixed public and private practices it is possible that the greater independence and autonomy associated with private practice confers upon them greater feelings of personal accomplishment that their peers working in state practices in other countries. Future research which contributes to our understanding of resilience and factors associated with personal accomplishment among Irish general practitioners would be of much use in facilitating understanding and the development of strategies to promote these feelings among general practitioners both in Ireland and internationally.

Recommendations for interventions

The high prevalence of burnout symptoms among our sample highlights the need for investigation, or implementation, of interventions to improve general practitioner well-being or strategies to reduce the work pressures of general practitioners in Irish settings. Stress management interventions provide a framework for both individual and organisational involvement in minimising stressful events and reactions.

Primary prevention

Primary prevention is concerned with an organisation taking actions to modify or eliminate sources of stress that are intrinsic to the work environment [23]. The UK’s Royal College of General Practitioners have recently published a consultation paper [24] that seeks to explore methods of reducing fatigue and burnout among general practitioners with the specific aim of reducing the threat posed to patient safety by impaired general practitioner well-being. The RCGP’s proposals for exploration include the imposition of frequent, obligatory breaks for general practitioners, the development of a procedure for identifying general practices with excessive workloads and means of reducing these work pressures, and an examination of means for reducing unnecessary workload (e.g., bureaucratic and administrative tasks) and work pressures.

Secondary prevention

This level of prevention is concerned with improving the prompt detection and management of stress and burnout. Secondary prevention interventions generally take the form of stress education and stress management training [23] and is the focus of most of the discussion on reducing burnout in general practitioners. A range of alternative intervention strategies targeting burnout among health professionals have also been investigated [25–27] such as psychosocial skills and communication training, multidisciplinary work shift evaluations as a means of improving team communication, cognitive behavioural training, counselling, and training in coping skills. However, although most interventions yielded improvements in burnout, these improvements do not persist over time [25].

Tertiary prevention

Tertiary measures are concerned with the treatment, rehabilitation, and recovery of individuals who have suffered, or are suffering, from ill-health as a result of stress and burnout [23]. Interventions at this level tend to involve the provision of counselling services for work or personal problems. For example, a Norwegian study [28] evaluated the efficacy of individual and group counselling programmes for stressed doctors. A 1-year follow-up identified significant reductions in emotional exhaustion, improvements in protective work practices (i.e., reductions in working hours), and reductions in the number of doctors on sick leave. The Irish College of General Practitioners has a confidential helpline that allows access to an employee assistance programme. However, greater investment in employee assistance programmes for Irish doctors may warrant further consideration; such services have been shown to yield a return on investment of between 3:1 and 15:1 by reducing the direct and indirect costs of stress in the workplace [23, 29].

Wallace and colleagues [30] have put forward an empirically based interventional model that addressed primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention of burnout. This model emphasises the importance of informing doctors about burnout and its impacts on the individual doctor and their patients, educating them on the workplace stressors (e.g., workload, emotional interactions, cognitive demands), contextual factors (e.g., culture of medical practice and associated lack of focus on personal well-being, lack of available resources for supporting physician well-being), and personal characteristics (e.g., personality traits, coping style, neglect of self-care) that contribute to symptoms of burnout, and teaching them practical skills to reduce their likelihood of experiencing burnout. The results of the current study, and previous research studies on this topic [5–8], regarding the demographic or other characteristics of general practitioners who are at high risk of experiencing emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation, or feelings of low personal accomplishment, may help guide the focus of such interventions or indicate the characteristics of general practitioners that should be included in research studies evaluating such interventions.

Limitations

The current study, employing a well-validated measure of burnout, offers an insight into burnout prevalence among more than a quarter of practicing general practitioners in Ireland [21]. However, in spite of these strengths, there are also limitations that should be considered when interpreting study outcomes. It is possible that our results may have been impacted by a participant self-selection bias whereby doctors who chose to participate may not be representative of the population as a whole. For example, it is possible that doctors experiencing high levels of stress or burnout were more interested in the research topic and more likely to participate than doctors experiencing low levels of stress or that doctors experiencing lower levels of stress were more likely to participate as they were under less pressure or experiencing less distress. Such possibilities are difficult to confirm or refute without larger scale investigations. However, the variance in participants’ demographic characteristics, and the large sample size, reduce this possibility. Furthermore, the reliance on participant self-report may also be considered a limitation of this study. The study outcomes may have differed where a more objective measurement system is employed. However, the MBI-HSS is the most commonly used and well-validated measure of burnout in existence and is considered the “gold standard” for measuring burnout among occupational groups [31]. It was also not possible to make any statistical comparison between the Irish sample of general practitioners and the international studies. This was because insufficient data were provided in the international studies to allow for more than a descriptive comparison to be made.

Future research

This study also suggests a number of directions for future research on this topic. While our study established the prevalence of burnout among Irish general practitioners, it did not examine causal factors of burnout in this population. Future research must, therefore, seek to investigate and determine factors that impact upon stress and burnout among general practitioners. An investigation of such variables, and Ireland-specific factors such as recent cuts in state funding as a result of the Financial Emergency in the Public Interest Act, may yield data that better guide interventions for, or strategies to improve, general practitioner well-being. Given the high prevalence of burnout symptoms observed in the present study, research examining the potential impact of burnout on general practitioner work performance and the standard of patient care delivered would also be of use.

Conclusions

Physician well-being has been described as a key quality indicator for healthcare systems [30], impacting hugely on the standard of patient care delivered. It is apparent from the results of this research study that the symptoms of burnout are prevalent among Irish general practitioners and may be negatively impacting on the quality of care that their patients receive. It is, therefore, imperative that causal factors be investigated and that interventions to improve well-being among Irish general practitioners be deployed on a national level.

References

Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP (2001) Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol 52:397–422

Shirom A, Melamed S, Toker S, Berliner S, Shapira I (2005) Burnout and health review: current knowledge and future research directions. Int J Rev Ind Organ Psychol 2005(20):269–308

Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, Dyrbye LN, Sotile W, Satele D et al (2012) Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Int Med 172:1377–1385

Shanafelt T, Sloan J, Habermann T (2003) The well-being of physicians. Am J Med 114(6):513–517

Arigoni F, Bovier PA, Mermillod B, Waltz P, Sappino AP (2009) Prevalence of burnout among Swiss cancer clinicians, paediatricians and general practitioners: who are most at risk? Support Care Cancer 17:75–81

Soler JK, Yaman H, Esteva M, Dobbs F, European General Practice Research Network Burnout Study Group (2008) Burnout in European family doctors: the EGPRN study. Fam Pract 25:245–265

Kushnir T, Cohen AH, Kitai E (2000) Continuing medical education and primary physicians’ job stress, burnout and dissatisfaction. Med Educ 34:430–436

Peisah C, Latif E, Wilhelm K, Williams B (2009) Secrets to psychological success: why older doctors might have lower psychological distress and burnout than younger doctors. Aging Ment Health 13:300–307

Gold KJ, Sen A, Schwenk TL (2013) Details on suicide among US physicians: data from the national violent death reporting system. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 35:45–49

Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, Russell T, Dyrbye L, Satele D, Collicott P, Novotny PJ, Sloan J, Freischlag J (2010) Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg 251:995–1000

Linzer M, Visser MR, Oort FJ, Smets EM, McMurray JE, de Haes HC, Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM), Career Satisfaction Study Group (CSSG) (2001) Predicting and preventing physician burnout: results from the United States and the Netherlands. Am J Med 111:170–175

Shanafelt T, Dyrbye L (2012) Oncologist burnout: causes, consequences, and responses. J Clin Oncol 30:1235–1241

Williams ES, Manwell LB, Konrad TR, Linzer M (2007) The relationship of organizational culture, stress, satisfaction, and burnout with physician-reported error and suboptimal patient care: results from the MEMO study. Health Care Manag R 32:203–212

Halbesleben JR, Rathert C (2008) Linking physician burnout and patient outcomes: exploring the dyadic relationship between physicians and patients. Health Care Manag R 33:29–39

Zenasni F, Boujut E, Buffel du Vaure C, Catu-Pinault A, Tavani JL, Rigal L, Jaury P, Magnier AM, Falcoff H, Sultan S (2012) Development of a French-language version of the Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy and association with practice characteristics and burnout in a sample of general practitioners. Int J Pers Cent Med 2:759–766

Bakker AB, Schaufeli WB, Sixma HJ, Bosveld W, Van Dierendonck D (2000) Patient demands, lack of reciprocity, and burnout: a five-year longitudinal study among general practitioners. J Organ Behav 21:425–441

Dyrbye LN, Massie FS, Eacker A, Harper W, Power D, Durning SJ, Thomas MR, Moutier C, Satele D, Sloan J, Shanafelt TD (2009) Relationship between burnout and professional conduct and attitudes among US medical students. JAMA 304:1173–1180

Orton P, Orton C, Gray DP (2012) Depersonalised doctors: a cross-sectional study of 564 doctors, 760 consultations and 1876 patient reports in UK general practice. BMJ open 2:e000274

Lee FJ, Stewart M, Brown JB (2008) Stress, burnout, and strategies for reducing them: what’s the situation among Canadian family physicians? Can Fam Physician 54:234–235

Maslach C, Jackson SE, Maslach Leiter MP, Manual Burnout Inventory (eds) (1996) Palo Alto, 3rd edn. Consulting Psychologists Press Inc., CA

Health Service Executive (2013) General practitioners or family doctors. http://www.hse.ie/eng/services/list/2/gp

Zwack J, Schweitzer J (2013) If every fifth physician is affected by burnout, what about the other four? Resilience strategies of experienced physicians. Acad Med 88:382–389

Byrne D, Buttrey S, Carberry C, Lydon S, O’Connor P (2015) Is there a risk profile for the vulnerable junior doctor? Irish J Med Sci 2015:2. doi:10.1007/s11845-015-1316-3

Royal College of General Practitioners (2015) Patient safety implications of general practice workload. http://www.rcgp.org.uk/policy/rcgp-policy-areas/~/media/Files/Policy/A-Z-policy/2015/RCGP-Patient-safety-implications-of-general-practice-workload-July-2015.ashx

Awa WL, Plaumann M, Walter U (2010) Burnout prevention: a review of intervention programs. Patient Educ Couns 78:184–190

Bragard I, Etienne AM, Merckaert I, Libert Y, Razavi D (2010) Efficacy of a communication and stress management training on medical residents’ self-efficacy, stress to communicate and burnout: a randomized controlled study. J Health Psychol 15:1075–1081

Sluiter JK, Bos AP, Tol D, Calff M, Krijnen M, Frings-Dresen MH (2005) Is staff well-being and communication enhanced by multidisciplinary work shift evaluations? Intensive Care Med 31:1409–1414

Rø KEI, Gude T, Tyssen R, Aasland OG (2008) Counselling for burnout in Norwegian doctors: one year cohort study. BMJ 2008:337

Cooper CL, Cartwright S (1994) Healthy mind; healthy organization—a proactive approach to occupational stress. Hum Relat 47:455–471

Wallace JE, Lemaire JB, Ghali WA (2009) Physician wellness: a missing quality indicator. Lancet 374:1714–1721

Schaufeli WB, Taris TW (2005) The conceptualization and measurement of burnout: common ground and worlds apart. Work Stress 19:256–262

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the contribution of Gorilla Survey and all participating general practitioners.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

This study did not receive any grant funding.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was granted by the research ethics committee of the Irish College of General Practitioners.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

O’Dea, B., O’Connor, P., Lydon, S. et al. Prevalence of burnout among Irish general practitioners: a cross-sectional study. Ir J Med Sci 186, 447–453 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-016-1407-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-016-1407-9