Abstract

In Ethiopia, cooperation among smallholder famers’ is a key element for managing and harvesting of agricultural crops and woodlot production. Despite the growing expansion and interest in eucalyptus woodlot production, not much has been done to characterize the type, form and level of cooperation among the smallholder farmers. Thus, this study analyses smallholder farmers’ cooperation on eucalyptus woodlot production in Wegera district, northern Ethiopia. Data collection involved focus group discussions, field observations, key informant interviews and semi-structured questionnaires administered to 120 producers selected using a systematic random sampling technique in three purposively selected kebeles (rural villages). A combination of data analysis methods, including descriptive statistics and econometric analysis (binary probit model), were used to analyze the data. The study revealed that two types of cooperation, informal and formal were identified and the level of cooperation was high since most smallholder farmers (80.8%) were found to participate in one or both of these systems. Further, the binary probit model shows that age (p = 0.007), family size (p = 0.026), membership status (p = 0.001), total livestock number (p = 0.011), woodlot size (p = 0.039), and working preference status of producers (p = 0.064) were significant variables in determining eucalyptus owners, decisions to cooperate. Informal cooperation constitutes an essential element in the production of eucalyptus woodlots especially in those activities like nursery preparation, transplanting, hoeing, harvesting and transporting. Based on the findings, formalization of informal institutions, execution of cluster planting to improve social relations and to settle eucalyptus related land use conflicts, and provide capacity building training to increase the level of awareness and use of cooperation benefits among producers are recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cooperation among humans is not a recent phenomenon. It has started by early Greece, Mesopotamia, Egypt, Rome, Babylon, American and African population groups. Since early agriculture would have been impossible without cooperation among farmers, they relied on one another to clear land, harvest crops, build shelters and share equipment (Bilmanis 1947; Lazdinis et al. 2005; Eshetu 2014; Schwettmann and Pardev 2014). In Ethiopia, though modern cooperatives were started after the 1960s, the formation of informal cooperation such as Edir (burial societies), Iqub (rotating small loan funds), Debo and Wonfel (communal labor), and Mahabir/Senbete (Christian religious cooperatives) date back many years (Bezabih 2009; Bernard et al. 2010). These traditional forms of cooperation are often reported as self-governing and highly respected organization performing various socio-economic, cultural and political activities (Gebre-Egzabher and Kumsa 2002; Veerakumaran 2007; Habtu 2012).

The rural communities in Ethiopia have a long history in management of forests and tree planting activities through cooperation (Eshetu 2014). During the Derge regime in the 1970s, there was mass mobilization and forced labor movement to rehabilitate degraded land including constriction of soil and water conservation structures and development of community forests and woodlots (Eshetu 2014). Smallholders have also used informal cooperation in their daily lives of agricultural land management and crop production as well as for woodlot managements at the farm level (Bezabih 2009; Habtu 2012). However, the development potentials of informal institutions/cooperation have been underutilized due to the absence of a legal framework with policies supporting these institutions (Hailu 2007).

In the context of forest cooperation, cooperation can be conceptualized (Fig. 1) as information, equipment, financial, and management cooperation which helps to share information, labor and equipment for harvesting and collective marketing of wood products to improve the income of producers (Corten et al. 1999; Kittredge 2005 and Lazdinis et al. 2005). Forest owners’ cooperation is critical and often developed due to an increase in social and environmental benefits from forests to the society and the globalization of wood product markets (Lazdinis et al. 2005). Forest owner’s cooperation helps to accomplish different tasks in forest production system like timber harvesting, collective marketing of forest products, wood trade, sharing information and reforestation in collaboration with forestry companies. It is beneficial to pool resources and actions so as to share risks and maximize benefits from forest development and management efforts both at small scale and industrial levels. Studies have also revealed that cooperation also helps to avoid conflicts and social obstacles and improves efficiency of production (Corten et al. 1999). From the perspective of the labour intensive forest management operations, cooperation is highly demanded by smallholders (Molla 2008). Similarly, mutual labor-sharing schemes for large, labor-intensive tasks, such as house construction, land clearing or crop harvesting can be found in most rural communities (Molla 2008; Schwettmann and Pardev 2014).

Smallholder forest plantations in different parts of the world are facilitated at all stages by government agencies, private enterprises and development agencies given potential contributions of plantations to rural development and livelihood improvements. For instance, eucalyptus plantation forestry in Paraguay has been facilitated by the government, private enterprises and development agencies due to the many roles of eucalyptus including as a source of timber for domestic and commercial purpose and for windbreaks and reforestation (Grossman 2015). This indicates the extent of cooperation in smallholder plantation development and commercialization not only among the smallholder farmers but also among government, private enterprise and development agents.

The decision to cooperate among smallholder farmers is moderated by several endogenous and exogenous factors which shall be investigated in this study in terms of the development and sustainability of including as a formal and informal cooperation. According to Aazamil et al. (2011), trust, number of family members, economic motivation and land ownership were the main socio-economic factors which affect rural women’s participation in productive cooperation in Iran. Nkurunziza (2014) stated that the main socio-economic factors that significantly affect farmers’ participation in coffee cooperatives in Rwanda were education level, farm size, gender, off-farm income, access to credit, and trust among members. Lack of cooperation was mentioned as the main constraint for land restoration projects (Rickenbach et al. 2004). Financial incentives and build relationships with landowner organizations were the main factors that fostered forest owners to actively participate in management and cooperation activities to protect biological diversity (Rickenbach et al. 2004). Likewise, Butler et al. (2017) revealed that financial incentives were the main method to increase cooperation rates among family forest owners in United States, but from the perspective of sustainability financial incentives were questioned. Asante et al. (2011) indicated that farm size, access to credit and access to machinery services were the main factors that influenced farmers’ decisions to join farmer organizations in Ghana. Education level, farm size and gross income play important roles in determining the probability of participation of farmers in cooperative (Frayne et al. 2008 cited in Nkurunziza 2014). Dedeurwaerdere (2009) stated that building of new forms of social cooperation was one of the mechanisms by which to foster social learning of sustainable forest management practices in Flanders.

The afformentioned studies highlighted the endogenous and exogenious factors mediating smallholder farmers, cooperation decisions and their motiviations to cooperate, both for agricultural crop production as well as for forest development and production. The determinants of smallholder decisions to cooperate are site specifics, dependent on the local socio-economic, environmental and institutional settings. Given the fast expansion of smallholder woodlot production in Ethiopia and in the study area, Wegera district, in particular, improving smallholder cooperation will have a significanrt contribution towards rural development of smallholder woodlot productions. However, not much research has been done in Ethiopia and on the factors affecting smallholder farmers’ decisions to cooperate in eucalyptus woodlot production. Therefore, this study was initiated to empirically answer the following three key research questions: (1) what are the existing types, forms, and levels of cooperation among smallholder farmers in terms of eucalyptus wood production in the districts? (2) What factors influence smallholder farmers’ decisions to cooperate in eucalyptus woodlot production? and (3) what are the opportunities and constraints of smallholder farmers’ cooperation for woodlot productions.

Research Methods

Description of Study Area

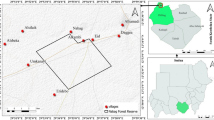

The study was conducted in the Wegera district of Amhara region, Ethiopia. It was selected owing to (1) the potential for eucalyptus woodlot production (2) the current expansion of eucalyptus plantations and (3) proximity to urban centers where there is growing demand for wood products. Wegera is one of the administrative districts in the North Gondar zone of Ethiopia (Fig. 2) situated about 36 km from Gondar town and found between 37.36°E and 12.46°N longitude. The altitude of district ranges from 1100 to 3040 m.a.s.l. The annual rainfall ranges between 1000 to 1200 mm and the minimum and maximum temperature is 14 °C and 33 °C, respectively. The rainy period extend from June until the end of September. However, most of the rainfall is received during the months of July and August (Derbe et al. 2018).

The district has a total area of 182,126 ha covered by cultivated land (46.1%), grazing land (22.7%), forest land (11.0%), buildings (4.4%), rivers and gorges (2.7%) and others (12.9%). The total population of the district is 268,833, of which 137,057 and 131,776 are male and female, respectively. The area is characterized by a mixed farming system (i.e., crop and livestock production). The main source of livelihood in the district is mixed agriculture including crop, livestock and forest plantation. The area is also known for its extensive area of eucalyptus globulus plantations (Dessie et al. 2019).

Methods of Data Collection and Sampling Procedures

Combinations of quantitative and qualitative data were gathered from relevant primary and secondary sources. Secondary data were collected from records of administrative offices and published and unpublished reports. Primary data were collected from producers and community leaders through household interviews, key informant interviews and focus group discussions.

The interview schedule consisted of semi-structured questions on the socio-economic, demographic and institutional characteristics of households. Prior to the actual data collection, the questionnaire was pre-tested and changes made accordingly. Focus group discussions were held two times involving a total of 24 eucalyptus woodlot producers. Face-to-face interviews were administered with a sample of 120 producers selected with a multi-stage sampling technique. In the first stage, Wegera district was purposively selected due to its high potential eucalyptus woodlot production. In the second stage, three kebeles (villages) namely, Kossoye, Ambagiorgis Zuria and Yesaq Deber were purposively selected out of 41 kebeles/villages/of the district, in consultation with Wegera districts Agriculture office experts due to the experience with eucalyptus woodlot production and plantations. In the third stage, using the kebele inhabitant list, a sample of 120 eucalyptus woodlot producers from the three kebeles were selected using systematic random sampling techniques following (Yamane 1967). The sample size was selected based on power analysis calculations (Eq. 1).

where n is sample size to be computed, N is target population in the study area (N = 2686) and e is the level of precision (e = 0.09).

Data Analysis and Model Specification

To effectively handle and analyse the data from the household heads, a combination of different descriptive analysis methods (frequencies, percentages, and means) and econometric models i.e., binary probit models were employed. Moreover, Pearson Chi square association analyses and t-tests were used to assess the associations and differences. Further, the qualitative data from the different group discussions was condensed, summarized using a strengths, weakness, opportunities and threat (SWOT) analysis.

A binary probit model was used to determine factors that influence producers’ decisions to cooperate in eucalyptus woodlot production. The variables included in the model were: age, family size in man day equivalents, marital status, institutional membership status, trust status of producers, working preference, woodlot size, total livestock number in tropical livestock unit and distance of wood lot to main road. Marginal effects were calculated and used for interpretation. A binary probit model was used due to the dichotomous nature of the dependent variable (1 for participant and 0 for non-participant). According to Maddala (1992) probit model are preferable over logit models due to its likelihood function giving more consistent maximum likelihood estimate (MLE) coefficients and standard errors. Several authors used binary probit model to analyze households decision to participate in various activities (e.g. Matshe and Young 2004; Sanchez 2005; Beyene 2008; Hagose and Zemedu 2015; Uzunoz and Akcay 2012). According to Greene (2003) and Maddala (1983), the binary probit for a two choice model is

The probit model is given by:

where Y* is latent dependent variable, X = explanatory variables (1, x1i, x2i,…,xki) and B = coefficients (β0, β1, β2…βk), e = error

Mathematically, this can be expressed as:

where a P(yes/no) is the probability of Smallholder farmer participate in cooperating, \(\beta_{0}\) is constant, \(\beta_{\text{i}}\) is a vector of parameters, \({\text{X}}_{\text{i}}\) is an explanatory variables and \(\mu_{\text{i}}\) is an error term.

The marginal effects provide insights into how the independent variables shift the probability of decision to cooperating. The marginal effect of the variables can be derived following Greene (2011):

where βi are coefficient of variables and φ represents the probability density function of a standard normal variable.

Multicollinearity test was as a model diagnostic test. Gujarati (2004) stated that Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) and contingency coefficient are used to check multicollinearity among continuous and discrete variables, respectively. As a rule of thumb, if the value of VIF is greater than 10, the variables are said to be highly collinear. Mathematically, this can be expressed in Eq. 6.

where VIF is variance inflation factor and R 2j is the multiple correlation coefficients between explanatory variables. Similarly, as a rule of thumb, if the value of CC is greater than 0.75, the variables are said to be collinear. Mathematically, this can be expressed in Eq. 7:

where CC—Contingency coefficient, χ2—Chi square test and N—Total sample size.

Table 1 show the effect of hypothesized explanatory variables on producer’s decisions to cooperate based on binary probit model. For instance, older people would be less likely to cooperate than younger. Cooperation work has good achievement than private working. Large woodlot size would have a significant and positive effect on forest/woodlot owners’ cooperation. Membership in a cooperative has a positive and significant effect on cooperation decisions activities. Marriage would increase social relation and the probability of cooperation among households. Trust can increase the probability of cooperation among households. Households with large family size would be less likely to cooperate with other households. Therefore, family size was hypothesized to have a negative and positive effect on decision to cooperating. The main sources of finance for most farmers are livestock so the rate of cooperation increases through livestock holding.

Results and Discussion

Socioeconomics and Institutional Characteristics

Eucalyptus woodlot producing households in the study area a dominantly male headed. The findings in Table (2) indicated that 91.7% of respondents were from male headed households and only 8.3% were female headed households. The household survey also revealed that the majority (80.8%) of the households participated in formal and informal cooperation in eucalyptus woodlot production (Table 2). The mean age of cooperating producers (50.7 years) was significantly lower (p = 0.01) than non- cooperating producers (60.7 years). This may give an indication of having more limited resources and family labour. This finding is in line with Rickenbach et al. (2004) who found that older forest owners are less likely to attend and cooperate in forest development council meetings than younger owners.

Household heads who were a member of institution such as Edir (burial societies) and Iqub (rotating small loan funds), have a higher probability of cooperating by sharing labor, information, tools and materials for woodlot production than non-members (Table 2). This finding is in line with the finding of Butler et al. (2017) who found that the rate of forest owners’ cooperation increases with financial incentives. Similarly, members of forest owners association were cooperating and planting more forest than non-members (Pollumae et al. 2013).

In terms of woodlot size, producers who cooperated had significantly higher (p = 0.1) average woodlot sizes (0.3 ha) than that of non- cooperated (0.2 ha). This implies that producers with large woodlots tend to cooperate more because of greater need for labor intensive woodlot management and harvesting tasks such as hoeing, cutting and transporting (Table 2). This study agrees with the finding of Rickenbach et al. (2004) who stated that the cross-boundary cooperation among forest owners positively correlated of landowners hold.

A higher proportion (57.5%) of the cooperating producers are significantly trust their partners (p = 0.01), while 23.3% of them lack trust with the cooperative partners (Table 2). Trust is a pre-request for cooperation and promotes social ties and cooperation habits of household heads in eucalyptus woodlot production. This is supported by the studies of Amdam (2001) and Dillman et al. (2014) who asserted that trust, tolerance and agreement about the facts are all cooperation pre-requisites and can increase cooperation rate of individuals.

Types, Forms and Level of Cooperation among Eucalyptus Producers

The study identified different types, forms and levels of cooperation used by household heads in the study area such as Debeyet (communal labor), Mahabir/Senbete (Christian religious cooperatives), and farmers development groups and cooperatives. Among these Debeyet and Mahabir/Senbete were informal types of cooperation where as farmers development groups cooperatives were formal types. Cooperating with other household heads in the short planting period and for follow up activities like weeding and hoeing; harvesting activities like cutting and transporting of woodlot products are the most common areas for cooperation besides seedling production (Fig. 3).

Each of the formal and informal types of cooperation vary and have their own organization and governance arrangements. Dabeyet is either organized as festive labor, where the host provides foods and drinks to his helpers, and/or as reciprocal labor sharing. Most household heads using Dabeyet could call on 5–8 people for support some others can call on up to 30. Mahabir and Senbete are Christian orthodox groups. In Mahabir the group gathers once a month to celebrate one saint (each group chooses and worships one saint only). Men and women can both be members. As key informants explained, these groups usually have not more than 15 members and are characterized by strong bonds via a local priest. In Senbete groups, women, men and priests take part with a usually higher number of members than Mahabir. The gatherings happen once a week after church services on Sundays. During their gatherings, members decide the date of cooperation in eucalyptus woodlot management and marketing. The members used such forms of cooperation particularly to plow, plant and transplant, hoeing and digging, harvesting and transporting of eucalyptus products. This result is consistent with Abtew et al. (2014) who reported farmer groups as an instrument of collective empowerment for more sustainable natural resource management. Moreover, Kittredge (2005) confirmed that potential benefits to cooperation among forest producers were sharing of equipments, proffesional services, joint marketing of wood, sharing knowledge/experience, finacial asistance, fire protection and reforestation. He also found that regional or local brand for wood products can create greater market place value.

Besides self-reporting of the respondents, different criteria were used to classify the level of cooperation among producers as high, medium, low and negligible. Those indicators include labor sharing, information sharing, membership of local institutions such as Edir (burial societies) and Iqub (rotating small loan funds), material and tools sharing, arriving on time plus commitment to work, social relations and distance of household head’s woodlot to residence, main road and market. Accordingly, the survey results revealed that the level of cooperation among smallholder farmers in woodlot production are higher under informal types of cooperation like Debeyet (communal labor) and Mahabir/Senbete (Christian religious cooperatives), than formal types of cooperation (such as Farmers Development Groups and Farmers Cooperatives) in the district. This is due to the fact that all members were organized in peer and voluntary with high levels of trust which justify that all cooperating members have equivalent status in most aspects particularly on labor, information, materials and tools sharing.

Woodlot Management Tasks

Smallholder producers in the study area use their cooperation for the accomplishment of different tasks in their eucalyptus woodlot production and marketing. To investigate these, the sampled respondents were asked on which eucalyptus woodlot production related activities they cooperate (Fig. 4). Household heads used Debeyet (communal labor), Mahabir/Senbete (Christian religious cooperatives), Farmers Development Group and Farmer’s Cooperatives to accomplish woodlot tasks, particularly by sharing of labor, production inputs, materials, tools and information. The results demonstrated that cooperation is highly demanded for planting and transplanting of eucalyptus seedlings (80.8%), hoeing (73.3%), cutting (59.2%), transporting (57.5%) and less demanded for nursery preparation (20.0%) and fencing (11.7%) (Fig. 4). This result was supported by Scheler (2016) who reported that households cooperated with each other by sharing land, labor, planting materials and tools to enhance eucalyptus woodlot production in Ethiopia.

Determinants of Smallholder Farmers’ Decision to Cooperate

We develop models of the determinants of smallholder farmers decision to cooperate. The likelihood ratio statistics as indicated by Chi square statistics were highly significant (p < 0.0000), suggesting the model has a strong explanatory power (Table 3).

The binary probit model revealed that the producer age (p = 0.007), family size (p = 0.026), institutional membership status (p = 0.001), total livestock number (p = 0.011), woodlot size (p = 0.039), and working preference status (p = 0.064) were significant variables influencing the smallholder farmers cooperation decisions. Regarding relationship between the variables and cooperation decision: membership status, total livestock number, and woodlot size of producers had positive relationships whereas age, working preference status and family size had negative relationship (Table 3).

Age of producer was significant (p < 0.01) and negatively influences producers’ decision to cooperating. The significantly, negative relationship between age and cooperation implies that younger producers are more likely to cooperate formally and or informally than older people. This means that younger producers can contribute more labor, ideas, inputs and tools. Consistent with these findings, Amoke et al. (2015) indicated that younger farmers are more likely to join cooperation organizations than the older farmers and was likewise consistent with the other previous studies (e.g. Karli et al. 2006; Geoffrey 2014; Hoken 2016).

As family size increase by a unit, the probability of decision to cooperate decreases by 0.6%, ceteris paribus. This implies that producers with large families did more labor intensive tasks using family labor than cooperative labor (communal labor). Similar results were reported by Jamilu et al. (2015) indicating that family size of respondents had a negative and significant effect on farmers’ cooperation in projects in Katsina State. Similarly, Ogunleye et al. (2015) also found family size was a significant factor that affects producers’ decision to cooperate in Oyo State.

Membership status of producers in other local institution such as Edir (burial societies), Iqub (rotating small loan funds), and some religious cooperatives was found to be positively correlated with decisions to cooperating. The model output indicated that the probability of producer’s decisions to cooperating increases by 90.3% as producers who were a member of local institutions. This implies as producers participate in local institutions, the probability to cooperate in eucalyptus woodlot production by sharing labor, production inputs and tools increases. Our study’s finding is in line with Jamilu et al. (2015) who indicated the membership of cooperative had a positive and significant effect on Nigerian row croppers’ cooperation decisions. Likewise, Mohamed (2004) also found that farmers in Egypt participate in informal social institutions such as wedding ceremonies, mourning ceremonies, patient visiting, visits exchange, lending and crediting could solve numerous socio-economic problems through cooperation. Moreover, forest owners in Estonia were cooperating and planting more forest than non-members (Pollumae et al. 2013).

As livestock holding increases by one TLU, increases the probability of households’ decision to cooperate by 0.3%, ceteris paribus. Livestock is an important source of income in rural areas which allows purchasing of farm inputs and tools. It is also exchanged for human labor for specific activities. Moreover, livestock serve as a means of transportation for eucalyptus woodlot products particularly by using horses, mules and donkeys (Bekele 2011).

The model results show that as woodlot size increases by one timad (0.25 ha), the probability of cooperating with other producers increases by 4.4%, ceteris paribus. This can be explained by the fact that, a producer that owns a larger woodlot needs more tools and labor to plant, hoe, harvest and transport. This finding agrees with Jamilu et al. (2015) who stated that farm size in Katsina State had a positive and a significant effect on cooperation decision. Similarly, Yahaya et al. (2013) reported that farm size of the cooperating farmers is found to be significant. Fischer and Qaim (2012) also revealed that the size of the land holdings in Kenya has a positive and a significant effect on the probability of membership in cooperation institutions.

Compared to individual work, producers who preferred mutual work decreases the likelihood of cooperation by 2.2%, ceteris paribus. This implies that some producers do not want to cooperate and work together due to a lack of trust and arriving late. Different behaviors of households and selfishness were the main factors which lead to a negative relation between work preference and cooperation participation. This finding is in line with Scheler (2016) who revealed that many times people do not arrive on the agreed time for mutual work, which is why they did not like to rely on cooperation.

SWOT Analysis of Cooperation Problems and Opportunities

Even though the empirical results pointed out those variables which were correlated with producers’ decisions to cooperate in woodlot production, producers also shared a number of other constraints and opportunities in the focus group that affected their cooperation habits in eucalyptus woodlot production (Table 4).

Conclusion and Recommendation

Cooperation among smallholder farmers’ has a significant role for the development of eucalyptus woodlot production and marketing systems. The producers used primarily four forms of cooperation, Debeyet (communal labour), Mahabir/Senbete (religious cooperative), Farmers’ Development Group and Farmers’ cooperative, to implement woodlot management and harvesting tasks like planting and transplanting, hoeing, weeding, harvesting and transporting eucalyptus seedlings and products. Debeyet and Mahabir/Senbete were informal types of cooperation whereas Farmers’ Development Group and Farmers’ cooperatives were formal. Furthermore, cooperation is a key element for conflict resolution between crop producers and eucalyptus producers, promoting and strengthening social ties among producers of the district. The decision to cooperate and the level of cooperation are determined by endogenous and exogenous factors like age of producers, woodlot size, social relation, trust, existence of informal institutions, commitment to work, and availability of production inputs and tools highly influenced the level and decisions to cooperate in eucalyptus woodlot production.

Development and policy interventions for further promotion and management of smallholder woodlot production should consider the significant factors mediating cooperation decision. Policy relevant variables such as institutional membership status, woodlot size and numbers of livestock had significant and positive effects on decisions to cooperate in eucalyptus production. Variables like family size, age and work preference status of producers had significant and negative effect on households’ decisions to cooperate in eucalyptus production. This implies producers with large families do many labor intensive tasks using family labor rather than communal labor. Likewise, age of households had a negative effect on decisions to cooperate in eucalyptus production implying younger producers is more likely to arrive on agreed time for mutual work and actively participate than elders.

Given the potential benefits of cooperation for the development of eucalyptus woodlot production and marketing in the study area and based on the study results, the following implications were found. Formalization of the informal cooperation/institutions will help to promote the extent of cooperation and social bounds among woodlot producers and serve as a means of tackling socio-economic problems by provide symmetric information, credit services, production, inputs, tools and materials on time. Hence, it is advisable to formalize the existing forms of informal types of cooperation institutions.

Executing cluster planting of woodlots is recommended so as to further promote cooperation among the smallholder producers and minimize the effects of eucalyptus plantations on the neighboring crop production fields. The plantation sites could be selected in consultation with experts so as to use marginal lands and restore degraded lands while minimizing competition of woodlot production with crop land. Further, it is recommended to pilot formalized institutional arrangement to improve the smallholders’ cooperation in eucalyptus woodlot production and evaluate its socioeconomic effectiveness.

References

Aazamil M, Sorushmehr H, Mahdei KN (2011) Socio economic factors affecting rural WP in productive cooperation: case study of Paveh ball-making cooperative. Afr J Agric Res 6(14):3369–3381

Abtew AA, Pretzsch J, Secco L, Mohamod TE (2014) Contribution of small-scale gum and resin commercialization to local livelihood and rural economic development in the dry lands of eastern Africa. Forests 5(5):952–977

Amdam J (2001) Future challenges for small-scale forestry-examples from the west coast of Norway. In: Economic sustainability of small-scale forestry. p 253

Amoke B, Taiwo A, Awoyemi T (2015) Factors influencing smallholder farmers’ participation in cooperative organization in rural Nigeria. J Econ Sustain Dev 6(17):87–97

Asante BO, Afarindash V, Sarpong DB (2011) Determinants of small scale farmers decision to join farmer based organizations in Ghana. Afr J Agric Res 6(10):2273–2279

Befekadu, A (2014) Role of cooperatives and participation of their members in agricultural output marketing: the case of Baso Liben Woreda, East Gojjam Zone. M.Sc. thesis presentes to Haramaya University, pp 1–97

Bekele M (2011) Forest plantations and woodlots in Ethiopia. Afr For Forum Work Pap Ser 1:1–51

Bernard T, Spielman DJ, Seyoum TA, GabreMadhin EZ (2010) Cooperatives for staple crop marketing: evidence from Ethiopia. International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington D.C.

Beyene AD (2008) Determinants of off-farm participation decision of farm households in Ethiopia. Agrekon 47(1):140–161

Bezabih E (2009) Cooperatives a path to economic and social empowerment in Ethiopia. International Labour Office, Dares Salaam

Bilmanis A (1947) Latvia as an Independent State. Latvian Legation, Washington, DC

Bjørnskov C, Dreher A, Fischer JA (2010) Formal institutions and subjective well-being: revisiting the cross-country evidence. Eur J Polit Econ 26(4):419–430

Butler BJ, Hewes JH, Butler SM, Tyrrell ML (2017) Methods for increasing cooperation rates for surveys of family forest owners. Small Scale For 16:169–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11842-016-9349-7

Corten I, Cordewener N, Wolvekamp P (1999) Revitalizing local forest management in the Netherlands: the woodlot owners’ association of Stramproy

Dedeurwaerdere T (2009) Social learning as a basis for cooperative small-scale forest management. Small Scale For 8:193–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11842-009-9075-5

Derbe T, Yehuala S, Agitew G (2018) Factors influencing smallholder farmers adoption of eucalyptus woodlot in Wogera District, North Gondar Zone, Amhara Regional State of Ethiopia. Int J Sci Res Manag 6(7):566–574. https://doi.org/10.18535/ijsrm/v6i7.em07

Dessie AB, Abtew AA, Koye AD (2019) Determinants of the production and commercial values of Eucalyptus woodlot products in Wogera District, Northern Ethiopia. Environ Syst Res 8(1):4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40068-019-0132-6

Dillman DA, Smyth JD, Christian LM (2014) Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: the tailored design method, 4th edn. Wiley, Hoboken

Eshetu AA (2014) Forest resource management systems in Ethiopia: historical perspective. Int J Biodiv Conserv 6(2):121–131

Fischer E, Qaim M (2012) Gender, agricultural commercialization, and collective action in Kenya. Food Secur 4(3):441–453

Frayne O, Theron, K, Gary G (2008) New generation cooperative membership: how do members differ from non-members? https://library.ndsu.edu/ir/bitstream/handle/10365/16335/ER40.pdf?sequence=1

Gebre-Egzabher, T. and Kumsa, A (2002) Institutional setting for local-level development planning in Ethiopia: an assessment and a way forward. Regional Development Studies (RDS), 3

Geoffrey K (2014) Determinants of market participation among small-scale pineapple farmers in Kericho County, Kenya. M.Sc. thesis presented to the school of graduate studies, Egerton University

Greene W (2003) Econometric analysis. Pearson Education Inc, Upper Saddle River

Greene W (2011) Econometric analysis. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River

Grossman JJ (2015) Eucalypts in agro forestry, reforestation, and smallholders’ conceptions of nativeness: a multiple case study of plantation owners in Eastern Paraguay. Small Scale For 14:39–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11842-0149272-8

Gujarati D (2004) Basic econometrics. Tata McGraw-Hill, United States Military Academy, West Point

Habtu K (2012) Classifying informal institutions in Ethiopia. Internship paper from development economics group, Wageningen University

Hagos A, Zemedu L (2015) Determinants of improved rice varieties adoption in Fogera district of Ethiopia. Sci Technol Arts Res J 4(1):221–228

Hailu A (2007) An Assessment of the Role of Cooperatives in Local Economic Development. Unpublished M.A. thesis presented to Addis Ababa University

Hoken H (2016) Participation in farmer's cooperatives and its effects on agricultural incomes: evidence from vegetable-producing areas in China (No. 578). Institute of Developing Economies, Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO)

Issa N, Chrysostome NJ (2015) Determinants of farmer participation in the vertical integration of the Rwandan Coffee value chain: results from Huye district. J Agric Sci 7(9):197

Jamilu AA, Atala TK, Akpoko JG, Sanni SA (2015) Factors influencing smallholder farmers participation in IFAD-community based agricultural and rural development project in Katsina State. J Agric Ext 19(2):93–105

Karli B, Bilgiç A, Çelik Y (2006) Factors affecting farmers’ decision to enter agricultural cooperatives using random utility model in the South Eastern Anatolian region of Turkey. J Agric Rural Dev Trop Subtrop 107(2):115–127

Kittredge DB (2005) The cooperation of private forest owners on scales larger than one individual property: international examples and potential application in the United States. For Policy Econ 7(4):671–688

Lazdinis M, Pivoriūnas A, Lazdinis I (2005) Cooperation in private forestry of post-soviet system: forest owners’ cooperatives in Lithuania. Small Scale For Econ Manag Policy 4(4):377–390

Maddala GS (1983) Limited dependent and qualitative variables in econometrics. Cambridge University Press, New York

Maddala GS (1992) Introduction to econometrics, 2nd edn. Macmillan Publishing Company, New York

Martey E, Wiredu AN, Asante BO, Annin K, Dogbe W, Attoh C, Al-Hassan RM (2013) Factors influencing participation in rice development projects: the case of smallholder rice farmers in Northern Ghana. Int J Dev Econ Sustain 1(2):13–27

Matshe I, Young T (2004) Off-farm labour allocation decisions in small-scale rural households in Zimbabwe. Agric Econ 30(3):175–186

Mohamed, F.A.S (2004) Role of Agricultural Cooperatives in Agricultural Development–The Case of Menoufiya Governorate, Egypt. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Land Development. Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms University: Mansoura

Molla DK (2008) Social networks and diffusion of agricultural technology: the case of sorghum in Metema Woreda, North Gondar, Ethiopia. Doctoral dissertation, Haramaya University

Nkurunziza I (2014) Socio-economic factors affecting farmers participation in vertical integration of the coffee value chain in Huye district, Rwanda. Doctoral dissertation

Nnadi FN, Akwiwu CD (2008) Determinants of youths participation in rural agriculture in Imo State, Nigeria. J Appl Sci 8:328–333

Ogunleye AA, Oluwafemi ZO, Arowolo KO, Odegbile OS (2015) Analysis of socio economic factors affecting farmers participation in cooperative societies in Surulere Local Government Area of Oyo State. Age 117(51.3):48–57

Olwande, J. and Mathenge, M (2012) Market participation among poor rural households in Kenya. In: International association of agricultural economists triennial conference, Brazil, pp 18–24 Aug

Pollumae P, Korjus H, Kaimre P and Vahter T (2013) Motives and incentives for joining forest owner associations in Estonia. Small-scale For (2014) 13:19–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11842-013-9237-3

Rickenbach MG, Bliss JC, Reed AS (2004) Collaborative, cooperation, and private forest ownership patterns: implications for voluntary protection of biological diversity. Small Scale For Econ Manag Policy 3(1):69–83

Sanchez V (2005) The determinants of rural non-farm employment and incomes in Bolivia. Doctoral dissertation, Michigan State University

Scheler J (2016) The impact of social capital on farm woodlot establishment, management and wood product marketing in Northern Ethiopia—the case of Wogera Woreda. Unpublished B.Sc. thesis presented to Dresden Technical Univerisity, Germany

Schwettmann J, Pardev I (2014) Cooperatives in Africa: success and challenges. ILO, Geneva

Uzunoz M, Akcay Y (2012) A case study of probit model analysis of factors affecting consumption of packed and unpacked milk in Turkey. Econ Res Int 2012:8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/732583

Veerakumaran G (2007) Ethiopian cooperative movement—an explorative study. Unpublished report Mekelle, Ethiopia

Yahaya H, Luka EG, Onuk EG, Salau ES, Idoko FA (2013) Rice production under the youth empowerment scheme in Nasarawa State, Nigeria. J Agric Ext 17(2):167–173

Yamane M (1967) Elementary sampling theory. Printice-Hall Inc., Englewood Cliffs

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the University of Gondar and “CHAnces IN Sustainability: promoting natural resource based product chains in East Africa (CHAINS)” project (BMBE Project-ID 01DG13017) funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research and organized by Technische Universitaet Dresden and University of Gondar.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dessie, A.B., Abtew, A.A. & Koye, A.D. Analysis of Smallholder Farmers’ Cooperation in Eucalyptus Woodlot Production in Wegera District, Northern Ethiopia. Small-scale Forestry 18, 291–308 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11842-019-09418-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11842-019-09418-4