Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this synthesis of qualitative studies is to explore manifestations of ambiguous loss within the lived experiences of family caregivers (FCG) of loved ones with cancer. Grief and loss are familiar companions to the family caregivers of loved ones with cancer. Anticipatory loss, pre-loss grief, complicated grief, and bereavement loss have been studied in this caregiver population. It is unknown if family caregivers also experience ambiguous loss while caring for their loved ones along the uncertain landscape of the cancer illness and survivorship trajectory.

Methods

We conducted a four-step qualitative meta-synthesis of primary qualitative literature published in three databases between 2008 and 2021. Fourteen manuscripts were analyzed using a qualitative appraisal tool and interpreted through thematic synthesis and reciprocal translation.

Results

Five themes were derived, revealing FCGs appreciate change in their primary relationship with their loved ones with cancer, uncertainty reconciling losses, an existence that is static in time, living with paradox, and disenfranchised grief. The results of this synthesis of qualitative studies complement the descriptors of ambiguous loss presented in previous research.

Conclusions

The results of this synthesis of qualitative studies complement the descriptors of ambiguous loss presented in previous theoretical and clinical research. By understanding ambiguous loss as a complex and normal human experience of cancer FCGs, oncology and palliative care healthcare providers can introduce interventions and therapeutics to facilitate caring-healing and resiliency.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

Untreated ambiguous loss can result in a decrease in wellbeing, loss of hope, and loss of meaning in life. It is imperative that cancer FCGs experiencing ambiguous loss are recognized and supported so that they may live well in the family disease of cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

With the advent of novel cancer treatments and increased patient survivorship rates, the impact of the cancer illness’s latent outcome is often extended for patients and their family caregivers (FCG) [1, 2]. The threshold for disease recurrence and possible death is raised, introducing a landscape of uncertainty and ambiguity for FCGs [1]. Within this space of ambiguity and heightened awareness of mortality [3], the cancer FCG may encounter emotional burdens and psychological distress such as chronic sorrow [4], heartbreaking hidden griefs [5], reduced closeness and connectedness [6], unknowns and uncertainty of the future [5, 7], emotional devastation [2, 5], and instability [6].

Ambiguous loss is defined as a situation “of unclear loss that remains unverified and thus without resolution” [8]. Ambiguous loss alludes to the ambiguity, emotional limbo, uncertainty, unfinishedness, and the circuitous and confusing nature of a physical or psychological loss as a relational phenomenon [8,9,10]. There are two types of ambiguous loss, the first type of ambiguous loss refers to a physically absent person who remains psychologically present in the family [8]. The unresolved physical absence of a family member can be due to kidnappings, disasters such as earthquakes and tsunamis, and the mysterious disappearances of airline flights. Due to the circumstances of physical ambiguous loss, families often do not know whether or not their loved ones are dead or alive. Families often describe physical ambiguous loss as “gone but not for sure” [8]. The second type of ambiguous loss is psychological and occurs when a loved one is physically present but perceived to be psychologically missing [11]. Family members describe psychological ambiguous loss as “here, but not here” [8]. A family member can be physically present yet missing psychologically due to the nature of living with chronic illnesses or disabilities, substance use disorders, and to cognitive impairment or memory loss as noted in persons with mental illness, brain injury, and dementia [8, 10].

The premise of the theory of ambiguous loss is anchored upon the assumption that ambiguous loss defies resolution as boundary ambiguities exist around who is in and out of a family, both physically and psychologically [8]. These boundaries are never absolutely clear and contribute to decreased wellbeing, loss of hope and meaning, and feelings of ambivalence. The ambiguity stems from relational processes that are frozen when a person is emotionally, cognitively, socially, or physically missing from the typical systems within a family. This loss is isolating and can be one of the most stressful losses as family members remain trapped between “hope and despair” [8].

The Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care [12] call for greater attention to the FCG assessment and the support of the family in coping with uncertainty, grief, loss, and the emotional aspects of caregiving. Despite the need to understand the importance of FCG wellbeing [13], few studies exist within the literature on the phenomena of ambiguous loss and the grief reactions of family members who may be experiencing the psychological loss of their loved one. These studies are among limited family populations, including persons with dementia [14] and brain-injured intensive care unit patients [9]. Presently, health research publications lack an exploration of cancer FCGs’ lived experiences and situational understanding of ambiguous loss. A meta-synthesis of existing qualitative research moves the field of health research forward as it illuminates situations and themes that were not evident prior, thus gaining a greater understanding of ambiguous loss to guide research and clinical practice in the cancer arena.

Research question

The research question for this review is, “How does ambiguous loss manifest in the lived experiences of FCGs of loved ones with cancer?” By extrapolating themes of ambiguous loss through a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies on the grief and loss experiences of FCGs of cancer patients, health research and clinical practice can be guided to support FCG wellbeing and quality of life domains as they care and live with their loved one during the oncological illness trajectory and survivorship.

Methods

A qualitative meta-synthesis design congruent with ENTREQ international standards for reporting and conduct [15] included: a structured research question and search strategy; quality appraisal and data immersion; theme analysis and reciprocal translation; and theoretical examination. Each published research study was considered a unit for analysis and not limited to reported participant text [16].

Procedures: search strategy, study selection, critical review, and sample

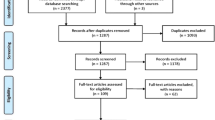

The literature search was conducted with the assistance of a large university medical campus health science librarian. Studies were identified utilizing the search engines PubMed, CINAHL, and PsycINFO. Cancer and grief were explored using PubMed MeSH terms and CINAHL “explode” option, which included the terms of loss, indefinite loss, ambiguous loss, uncertainty, and cancer and neoplasm. A combined approach of thesaurus terms and free-text terms maximized the number of potentially relevant articles. The terms caregiver, carer, and qualitative research were added to the search. The Boolean operators “and” and “or” were used to expand and narrow the search parameters (see Fig. 1). The electronic search was supplemented by data-driven manual searches using the primary reference list of the selected studies.

FCGs were defined as family members, life partners, or friends who provide and maintain a substantial level of unpaid daily care, including physical, emotional, and often financial support, to another person who cannot care for themselves without the caregiver’s assistance [12, 17]. The inclusion criteria for this study included: (a) utilized qualitative methods; (b) utilized interview data collected from cancer FCGs; (c) were published between 2008 and 2021; (d) contained the presence of cancer in the loved one of any type and stage. Recognizing the literature in cancer research is ongoing and evolving; the search for publications was initially 10 years (2010–2020) to capture significant and timely research findings. The search was expanded to 2008–2021 due to this study’s timeline extension and the decision to include multiple primary referenced articles. Exclusion criteria for the study were: (a) quantitative, mixed methods, and meta-synthesis qualitative studies, as these either did not utilize qualitative methodology or were involved in layers of interpretation which would limit the ability to synthesis across one method of research as used in this study’s meta-synthesis technique [15]; (b) articles whose patient population focused on pediatrics, exclusive bereavement grief, or non-cancer diagnoses; and (c) articles whose caregivers were professional healthcare workers.

The PRISMA (see Fig. 1) details the article selection process in each step from identification (n = 146), duplicate citations removed (n = 39), and screening through titles and abstracts to reject an additional 61 articles. The process yielded a total of 46 articles for full text review. Retrieved abstracts and titles were screened for potential eligibility by two reviewers (CW, CB). After conducting a methodological critical review, 14 articles remained relevant for further analysis per our study inclusion criteria.

Research team members (CW, CB, AG) reviewed the included qualitative studies by critiquing 17 items relevant to the study’s methodology, analyses, and rigor by utilizing the McMaster University method for quality appraisal [18]. The tool [18] evaluated rigor by the four components of trustworthiness: credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability, as criteria initially identified by Guba and Lincoln in 1985 [19, 20]. The research team reviewed the findings of the appraisals through team discussion and jointly decided that 14 of the articles met the requirements of the methodological critical review. The findings from the critical review and characteristics of the 14 articles included in this meta-synthesis are summarized in Table 1. Articles were published between 2008 and 2019 with sample sizes ranging from 7 to 92. The total number of participants interviewed was 323 adults, composed of 204 females and 119 male FCGs. Most of the participants reported in the articles were Caucasian female spouses of a loved one with cancer, with a median age of 57 years. The principal study design utilized phenomenology methodology.

Data analysis

The aim of a meta-synthesis is to produce from a body of qualitative research literature new knowledge beyond its primary studies [16]. The process of integrating new knowledge involves reviewing the data through the interpretive study of interpretations using thematic synthesis for systematic review [32]. We used social constructivist assumptions as the meta-synthesis framework, which situates knowledge within lived experiences, that individuals can perceive multiple realities, and that description is a process of deepening interpretation where language is the means to convey meaning through interactions [16, 33].

The collection of qualitative articles was analyzed for themes using an inductive approach, allowing for the generation of key themes [34, 35]. The articles were read in their entirety by the first researcher (CW), line by line, and reviewed for themes of grief and loss. The team then evaluated the themes and defined theme labels through group discussions. Space and time were permitted for the deconstruction and reconstruction of patterns, assumptions, and interpretations to be produced. Through our reflexive attendance to the sensitive nature of the contextual human experiences of loss and grief, new meanings, themes, and subthemes were discovered, adding credibility to this study.

Findings

Through the process of interpretive integration adapted from Noblit and Hare [36], known as reciprocal translation, an evidentiary matrix of newly derived themes and subthemes was mapped back to the original studies from which the themes were grounded (see Table 2). The final list of themes was cross analyzed deductively with descriptors of the assumptions of the ambiguous loss theory [8, 11] to identify possible characteristics of ambiguous loss (see Table 3) within the content of this body of qualitative articles. Thus, the final analytic question was: How does ambiguous loss theory relate to the derived themes through similarities and differences? This process helped identify patterns of ambiguous loss for future study.

The themes that inform “ambiguous loss as manifested in the lived experiences of FCGs of loved ones with cancer” are: (a) changes in the primary relationship, (b) uncertainty reconciling loss, (c) living with paradox, (d) static in time, and (e) grief that is hidden. Refer to Table 4 for additional illustrative FCG participant quotes for emphasis.

Constantly changing landscape is the thematic thread woven throughout the patterns of ambiguous loss, as manifested in all the themes by common and unique features aggregated and interpreted within and across all 14 studies. The relational reality of these FCGs was compromised [26], and the life they knew before the cancer illness had been rearranged into an ongoing situation that lacked closure and resolution. The equilibrium of the relationship with their loved one and the life they knew together collapsed as the illness introduced a series of unpredictable changes and unknowns. This overarching theme illustrates how FCGs were often unsure of what lay ahead while caring for their loved ones with cancer, as the landscape in front of them was constantly changing, unclear, and unpredictable [27]. They lived in the “Day to day of not knowing…every day presents something different” [24].

Changes in the primary relationship

FCGs often experienced role dissonance and the development of new roles within their existing relationships with their loved ones with cancer.

For him to become ill was like it defied all truths that we understood to be true, that he would be the leader and the protector and we would be embraced by his protection. I wanted to step in there and look after him and try to make everything better, which of course I couldn’t [25].

They took on the roles of primary emotional supporter and caregiver, both roles they had not had before the illness of cancer [6, 28, 31].

FCGs often experienced a loss of intimacy and reciprocity in the primary relationship [6, 30]. They felt unable to share their emotions with their sick loved ones, which led to a lack of connectedness [6]. The normative roles in the relationship, particularly between the spouse and partner, were often placed on hold as the partner with cancer became a patient [28]. These relationship changes often led to a shift in the balance [30] and a decrease in physical and emotional intimacy [6, 21, 30]. As their loved ones with cancer physically changed, the FCGs bore witness to the physical “wasting away” [24] and suffering [6, 25, 30], even to the extent in which they could not recognize the person for whom they loved [29].

Yet, the FCGs often maintained efforts to remain interconnected [31] and lighten the other’s burden. One participant stated, “I come home to be there for whatever he needs” [31]. Sometimes they noted positive changes such as increased emotional closeness, strengthened partnership, improved attitudes, and greater physical closeness [2, 6, 21, 23, 30].

Uncertainty reconciling loss

FCGs were uncertain of their loved one’s future, including when to expect a response to treatment, recurrence of disease, or a decline of health [28]. Every day they were in a state of flux of not knowing [30, 31]. Prognostic information was often vague, and illness trajectories were unpredictable [1, 21]. Cancer was “A cloud of metastatic possibilities hanging over them; you can see it [death] sort of looming” [1].

Subtheme: grief with unpredictability of fate or future

Living in constant uncertainty, FCGs stopped looking ahead as they felt as if they were living on bonus time. They experienced an inability to plan as thoughts of the future were forbidden since these thoughts conflicted with the present life of holding on to the now [37]. The FCGs were unable to reconcile the loss they were presently living. They felt like they had nothing to look forward to, and they experienced the loss of future hopes and dreams of what could have been [27, 28]. These included the loss of retirement, jobs, and plans with their loved ones [1, 27]. One participant said, “We have a little grandchild, and she’s only 15 months old. It’s hard for my husband to reconcile that he’s not going to see much of her growing up… I think that’s the most difficult thing for him, and for me…” [21]. FCGs mourned the lost sense of a clear mutual future, assumptions, and non-specific choices about their lives [1, 21, 27, 28].

Subtheme: uncertainty creates negative caregiver emotions

As FCGs experienced uncertainty, they felt shame and guilt [6, 21, 27] as they experienced moments when they considered planning for the future without their loved ones, asking, “Why am I having these thoughts?” [1]. They experienced guilt for doing things for themselves, as was noted by one caregiver: “If I am earning money I feel guilty because you know, money, guilt, time” [23]. They often lived in constant states of worry, anxiety, and fear about their loved ones’ present and future health [28]. FCGs felt powerless to relieve the suffering they often witnessed [30] and, “Stand totally helpless and alone” [6].

Living with paradox

The FCGs found existential meaning in striving to be present with their loved ones while grieving the past and planning for the future [21]. They sometimes found meaning, hope, and joy [6, 31] in reflections on the meaning of the circle of life and death and in making memories [29]. The simultaneous holding space of two opposing ideologies is known as paradox [26]. FCGs noted paradoxical presence in the embodied coexistence of suffering and joy with loss and relief [6, 22]. Some FCGs could banish thoughts of a tragic looming loss to engage in being fully present while discovering peace and gratitude [25, 37]. One caregiver stated, “I know these things are really bad, but in the face of bad things you always try to be positive, you want there to be a cure…an optimistic attitude is as important as the drugs, and that for me came first” [31].

FCGs continually sought hope of a good outcome for their loved ones [30]. While often recognizing that their loved ones’ wishes for cure were unlikely to come true, many FCGs could transition their hope into more realistic expectations [21]. “I just said I wanted him to be comfortable, pain managed well, that his spiritual needs were met” [21]. Additionally, the uncertainty of their loved one’s disease trajectory allowed some FCGs to postpone the threat of the inevitable outcome [6, 24, 30]. This postponement gave the FCGs space to hope for alternative results such as recovery and a longer life for their loved ones [21, 30]. “We do not know what will happen next. He has always recovered after coming to the hospital. I’m always holding on to this hope” [30].

Static in time

Subtheme: state of suspension-emotional limbo

FCGs’ lives often became suspended as they did not know what the future held, and they stopped making plans for themselves [27, 28, 30]. Time stood still, and the sense of time became altered as identified by one participant: “I do feel like life is on hold to be honest…like we’re just stagnant at the moment” [27]. Caregivers often felt immobilized or paralyzed in their life courses as they could not plan or make decisions; they could not go back or move forward [1, 27, 28]. Life around them went on autopilot as their focus shifted to their loved ones [31]. They banished thoughts of the possible loss of life and focused only on the here and now [37].

Subtheme: living in the memories

Within the stasis of time, the FCG sometimes longed to sustain their loved one within the life and bond they shared in the past, before cancer [22]. Caregivers would reflect upon the significance of their loved one’s contribution to their families and communities by telling stories [21]. They desired to live in the past life of happier, healthier days as they remembered and reconstructed memories of their loved ones [22]. One participant reflected upon her alcoholic spouse, whom she wanted to be seen as a good person:

He’s had a hard life. He was taken into the army when he was 14 years old. He didn’t find his parents for two years afterwards in Europe. Then he came to Canada and worked a double contract so that when his parents and his brother came they wouldn’t have to. So life has not been easy for him [21].

As their relationships with their loved ones continued but changed [22], FCGs found an internal grounding, peace, and appreciation for life by reflecting upon the good times and memories [25].

Grief that is hidden

The FCGs in these studies often expressed feeling the emotional burden of bearing their grief alone [6, 29, 31], without witness or social support [22]. It was understood that, “People do not want to talk about things that are sick” [6]. Mourning occurred behind the veil in private moments, after meeting the patients’ and family members’ needs [22]. Grief was often held inward, “Trying to create that sense of I would be okay, that we would all be okay” [22], to protect and spare others, including the loved one with cancer, their children, and the elderly from experiencing distress and further emotional pain [30, 31, 37].

Discussion

This study introduces an unknown aspect of cancer FCGs lived experiences of grief and loss by illuminating themes of ambiguous loss. The family theory of ambiguous loss has multiple underlying theoretical assumptions [8] and propositions [11], which have been identified over time by social scientists working with populations across many cultural contexts. These assumptions were deductively explored in relation to the team derived themes to further contextualize and develop new knowledge of ambiguous loss (see Table 3). The first theme change in the primary relationship reveals the significance of ongoing change and transformation in the cancer FCG’s lived experience of ambiguous loss. FCGs experience significant relationship alterations secondary to changes in their loved ones due to the nature of the cancer illness and its oncological treatment regimens. There is potential for loss of connection and support vital to the relationship, resulting in a psychological absence, “here but not here,” referred to as psychological ambiguous loss [8]. While this meta-synthesis noted the presence of positive changes in some of the primary relationships, we consider these findings counter stories to the dominant stories of cancer FCGs. Yet these findings may speak to the reconstruction of identities within relationships as a means for people to overcome the trauma and loss introduced by cancer and remain resilient and healthy through relational connections [26].

The second theme of uncertainty reconciling losses and the grief with unpredictability of fate or future reveals the presence of not knowing and the unattainable nature of truth, essential assumptions of ambiguous loss. With ambiguous loss, the loss and grief remain open and without resolution. The expectations surrounding the illness of cancer, including the prognosis and treatment trajectory, often remain unclear. Grief accompanies the uncertainty of not knowing what will happen to their loved ones or themselves. Truth is not attainable, and closure is a myth. There lacks the mastery of finding answers to a problem [38] regarding the expected illness outcome of the FCG’s loved one [31]. Cancer FCGs can be encouraged to re-define their hopes as hope-in-the-moment, accept truth as truth-in-the-moment [39], and reorient away from the urge to control and master outcomes.

The third theme, living with paradox, unveils the mystery of opposite qualities contained within the whole [8]. Paradox signifies the cancer FCG’s experience of simultaneous holding on and letting go while riding the “emotional roller coaster” [6, 40]. Ambiguous loss manifests in a chaotic pattern of “up and down, back and forth” [38], by which FCGs create new ways of rationalizing and making sense of the world around them through the regulatory oscillating process of balancing conflicting demands [30]. This theme recognizes the need for individuals to hold space for conflicting thoughts without the pressure and tension to label and define their experiences and thoughts dualistically. Healthcare providers can encourage FCGs to manage the tensions of polarity thinking by allowing and nurturing space for both-and thoughts, such as “my loved one is both sick and well, or both dying and alive.”

The process of ambiguous loss is understood to be circular and continuous, resulting in immobility, both socially and psychologically [8], as manifested in the fourth theme of static in time. The FCG feels trapped in their inability to find closure to their losses, poignantly described in this participant population as being paralyzed in time, living day-by-day [27, 30]. FCGs related to putting life on hold, delaying decisions, and implementing previously made plans for the future. As a consequence of ambiguous loss, FCGs can experience a state of emotional limbo while living in the memories, which can be misunderstood and mislabeled as depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and complicated grief [10, 38]. This theme also speaks to the need for healthcare providers to accept the normality of ambiguity present in the cancer loss experience and avoid the urge to label the grief in the loss as a stage of grief to overcome or a mental health crisis. These diagnoses and labels are reductionist and overlook, misunderstand, and minimize the complex lived experience of ambiguous loss. Additionally, misunderstanding this loss can delay acceptance and the delivery of interventions that are vital to a person’s healing.

The final theme, grief that is hidden, also known as disenfranchised grief [41], is a common finding of ambiguous loss [10]. Society often does not know how to legitimize loss and grief and provide the support required to grieve when these losses are non-death-related [42], as experienced in palliative and survivorship trajectories. Disenfranchised grief can occur when a loss is not acknowledged, there is an exclusion of the griever, and when society fails to recognize the relationship of the loss to the griever [41]. When grief is hidden and disenfranchised, FCGs lack opportunities to share their loss, and therefore they suffer alone in silence, without social and empathetic support required to heal [43]. This theme is supported in a recent study that found cancer FCGs were co-afflicted but invisible and felt not seen or heard by healthcare providers, friends, and family members [44]. Cancer FCGs need safe spaces to be seen, carry their sadness, and openly grieve as they search for and create meaning when the cancer disease itself is meaningless. Empathetic and compassionate human connections are required for healing. The social recognition of ambiguous loss can promote individual resiliency required for FCGs to tolerate a life of uncertainties.

Implications for research and practice

By integrating what is known about ambiguous loss from work completed within the social science paradigm [8, 11, 26] with a human science person-centric dynamic framework, FCGs’ humanity and lived experiences of loss can be further contextualized to evolve the constraining and reductionist bio-medical models of care. A collaborative theoretical framework that lends itself to intradisciplinary endeavors may assist oncology nurses and healthcare providers in supporting FCGs’ experiences of ambiguous loss as an acceptable and normal human response to health and the environment. The Resilience Framework for Nursing and Healthcare [45] can guide nurses and healthcare providers in assisting cancer patients and FCGs in identifying and using coping mechanisms that build resilience. The process of becoming resilient is active and incorporates strategies and therapeutic programs intending to acquire a state of equanimity defined as personal acceptance of the impact of the current health situation.

Ambiguous loss theorists and clinicians have identified therapeutic practices and modalities to include those which strengthen resiliency [46], normalize uncertainty [13], reframe meaning [43], create and redefine hope, facilitate the reconstruction of identity, and reorient away from mastery and control when closure is not an option [8, 26, 38, 47]. The Resilience Framework for Nursing and Healthcare identified common coping concepts for illness caregivers including: acceptance, knowledge, mastery, meaning finding, optimism, resourcefulness, self-care, social support, and spirituality [45]. An evolved and intradisciplinary theoretical model of care that incorporates and builds upon the concepts introduced in this framework may provide oncology nurses and healthcare providers in research and clinical practice with language, new patterns of knowing [48], and a holistic lens to introduce practices of care for FCGs across all quality of life domains [13]. Facilitating practices and therapies which promote resiliency can strengthen FCGs to carry the not-knowing and live well in the ambiguity and loss introduced by the cancer illness.

Strengths and limitations

This meta-synthesis utilizes an international body of qualitative literature on the lived experience of oncology FCG grief and loss within the context of uncertainty. While the findings identified in this study may not represent all cancer FCGs, they provide a situational understanding of the manifestations of ambiguous loss in FCGs of cancer patients with various cancer diseases and stages. Individual differences may exist in experiences of ambiguous loss in relation to the type and stage of the cancer of the family member and other factors not described in this review. A strength of a meta-synthesis is the interpretation of themes second-hand through a review of data and synthesis of information previously obtained by another researcher, which increases the confidence that themes identified across studies are pertinent. We recognize that a meta-synthesis does not offer researchers access to the full data sets of the original qualitative research. As the data analysis in a meta-synthesis is inherently subjective, we acknowledge that our knowledge and experience of ambiguous loss, grief, and the oncology arena are reflected in this research’s data analysis, discussion, and results. Although participants were not excluded based on age, ethnicity, or gender, we noted the lack of ethnic and racial representation. The predominant gender represented was women, while common among caregiver populations for elective studies, was reported to be a limitation in multiple articles. We consider the inclusion of bereaved caregivers as a limitation [1, 6, 21, 22, 25, 27, 29, 30], as bereavement grief could alter the stories of the FCG’s loss experience while caring for their loved one while they were living.

Conclusion

This meta-synthesis of qualitative literature provides new insight into the patterns of ambiguous loss that may underpin FCGs’ lived experiences while caring for their loved ones with cancer. Ambiguous loss is a unique type of loss and can contribute to an individual’s decrease in wellbeing, loss of hope and meaning in life. We invite oncology nurses and other healthcare providers to accept the normality of ambiguity present within the ongoing loss experiences of cancer FCGs and encourage practices of care that foster resiliency and tolerance of uncertainties.

References

Olson R. Indefinite loss: the experiences of carers of a spouse with cancer. Eur J Cancer Care. 2014;23(4):553–61.

Ponto JA, Barton D. Husbands’ perspective of living with wives’ ovarian cancer. Psychooncology. 2008;17(12):1225–31.

Carroll JS, Olson CD, Buckmiller N. Family boundary ambiguity: a 30-year review of theory, research, and measurement. Fam Relat. 2007;56(2):210–30.

Hainsworth MA, Eakes GG, Burke ML. Coping with chronic sorrow. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 1994;15(1):59–66.

LeSeure P, Chongkham-ang S. The experience of caregivers living with cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-synthesis. J Pers Med. 2015;5(4):406–39.

Pusa S, Persson C, Sundin K. Significant others’ lived experiences following a lung cancer trajectory—from diagnosis through and after the death of a family member. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2012;16(1):34–41.

Sherman DW, McGuire DB, Free D, Cheon JY. A pilot study of the experience of family caregivers of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer using a mixed methods approach. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2014;48(3):385-99.e2.

Boss P. The context and process of theory development: the story of ambiguous loss. J Fam Theory Rev. 2016;8(3):269–86.

Kean S. The experience of ambiguous loss in families of brain injured ICU patients. Nurs Crit Care. 2010;15(2):66–75.

Knight C, Gitterman A. Ambiguous loss and its disenfranchisement: the need for social work intervention. Fam Soc. 2019;100(2):164–73.

Boss P. Ambiguous loss research, theory, and practice: reflections after 9/11. J Marriage Fam. 2004;66(3):551–66.

Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, 4th Ed. [Internet]. National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care. 2018 [cited August 1, 2021]. Available from: https://www.nationalcoalitionhpc.org/ncp.

Ferrell BR, Kravitz K, Borneman T, Friedmann ET. Family caregivers: a qualitative study to better understand the quality-of-life concerns and needs of this population. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2018;22(3):286–94.

Liew TM, Tai BC, Yap P, Koh GC. Development and validation of a simple screening tool for caregiver grief in dementia caregiving. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):54.

Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, Oliver S, Craig J. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12(1):181.

Sandelowski M. Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. Barroso J, editor: New York: Springer Pub. Co.; 2007.

Hudson PL. How well do family caregivers cope after caring for a relative with advanced disease and how can health professionals enhance their support? J Palliat Med. 2006;9(3):694–703.

Letts L, Wilkins S, Law M, Stewart D, Bosch J, Westmorland M. Guidelines for critical review form: qualitative studies (Version 2.0). McMaster university occupational therapy evidence-based practice research group. 2007.

Koch T. Establishing rigour in qualitative research: the decision trail. J Adv Nurs. 2006;53(1):91–100.

Guba EG. Fourth generation evaluation. Lincoln YS, editor: Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1989.

Sutherland N. The meaning of being in transition to end-of-life care for female partners of spouses with cancer. Palliat Supportive Care. 2009;7(4):423–33.

Bouchal SR, Rallison L, Moules NJ, Sinclair S. Holding on and letting go: families’ experiences of anticipatory mourning in terminal cancer. Omega (Westport). 2015;72:42–68.

Olson RE. A time-sovereignty approach to understanding carers of cancer patients’ experiences and support preferences. Eur J Cancer Care. 2014;23(2):239–48.

Mosher CE, Adams RN, Helft PR, O’Neil BH, Shahda S, Rattray NA, et al. Family caregiving challenges in advanced colorectal cancer: patient and caregiver perspectives. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(5):2017–24.

Rodenbach RA, Norton SA, Wittink MN, Mohile S, Prigerson HG, Duberstein PR, et al. When chemotherapy fails: emotionally charged experiences faced by family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(5):909–15.

Boss P. Loss, trauma, and resilience: therapeutic work with ambiguous loss: New York: WW Norton & Company; 2006.

Shilling V, Starkings R, Jenkins V, Fallowfield L. The pervasive nature of uncertainty-a qualitative study of patients with advanced cancer and their informal caregivers. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;11(5):590–603.

Röing M, Hirsch J-M, Holmström I. Living in a state of suspension—a phenomenological approach to the spouse’s experience of oral cancer. Scand J Caring Sci. 2008;22(1):40–7.

Dumont I, Dumont S, Mongeau S. End-of-life care and the grieving process: family caregivers who have experienced the loss of a terminal-phase cancer patient. Qual Health Res. 2008;18(8):1049–61.

Coelho A, de Brito M, Teixeira P, Frade P, Barros L, Barbosa A. Family caregivers’ anticipatory grief: a conceptual framework for understanding its multiple challenges. Qual Health Res. 2020; 30(5):693–703.

Quinoa-Salanova C, Porta-Sales J, Monforte-Royo C, Edo-Gual M. The experiences and needs of primary family caregivers of patients with multiple myeloma: a qualitative analysis. Palliat Med. 2019;33(5):500–9.

Dixon-Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D, Young B, Sutton A. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10(1):45–53.

Paterson BL, Thorne SE, Canam C, Jillings C. Meta-study of qualitative health research. a practical guide to meta-analysis and meta-synthesis: Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001.

Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval. 2006;27(2):237–46.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Noblit GW, Hare RD. Meta-ethnography: synthesizing qualitative studies: Newbury Park, CA:Sage; 1988.

Sjolander C, Hedberg B, Ahlstrom G. Striving to be prepared for the painful: management strategies following a family member’s diagnosis of advanced cancer. BMC Nurs. 2011;10(1):1–8.

Boss P. The trauma and complicated grief of ambiguous loss. Pastoral Psychol. 2010;59(2):137–45.

Parse RR. Human becoming: Parse’s theory of nursing. Nurs Sci Q. 1992;5(1):35–42.

Ferrell BR, Smith TJ, Levit L, Balogh E. Improving the quality of cancer care: implications for palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(4):393–9.

Doka KJ. Disenfranchised grief: recognizing hidden sorrow. Maryland: Lexington Books; 1989.

Doka KJ. Disenfranchised grief: new directions, challenges, and strategies for practice: Champaign, IL: Research PressPub; 2002.

Weiss, C. Concept analysis of disenfranchised grief within a nursing paradigm, to awaken our caring humanity. Int J Hum Caring. 2021;Manuscript accepted for publication.

Tranberg M, Andersson M, Nilbert M, Rasmussen BH. Co-afflicted but invisible: a qualitative study of perceptions among informal caregivers in cancer care. J Health Psychol. 2021;26(11):1850–9.

Morse JM, Kent-Marvick J, Barry LA, Harvey J, Okang EN, Rudd EA, et al. Developing the resilience framework for nursing and healthcare. Glob Qual Nurs Res. 2021;8:23333936211005475.

Masten AS. Resilience in the context of ambiguous loss: a commentary: resilience in ambiguous loss. J Fam Theory Rev. 2016;8(3):287–93.

Ferrell B, Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association. Spiritual, religious, and cultural aspects of care: New York: Oxford University Press; 2015.

White J. Patterns of knowing: review, critique, and update. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 1995;17(4):73–86.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by CW, CB, and AG. The qualitative methodology was guided by JJ. The first draft of the manuscript was written by CW, and all authors commented on subsequent versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Weiss, C.R., Baker, C., Gillespie, A. et al. Ambiguous loss in family caregivers of loved ones with cancer, a synthesis of qualitative studies. J Cancer Surviv 17, 484–498 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-022-01286-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-022-01286-w