Abstract

Purpose

Many caregivers take paid and/or unpaid time off work, change from full-time to part-time, or leave the workforce. We hypothesized that cancer survivor-reported material hardship (e.g., loans, bankruptcy), behavioral hardship (e.g., skipping care/medication due to cost), and job lock (i.e., staying at a job for fear of losing insurance) would be associated with caregiver employment changes.

Methods

Adult cancer survivors (N = 627) were surveyed through the Utah Cancer Registry in 2018–2019, and reported whether their caregiver had changed employment because of their cancer (yes, no). Material hardship was measured by 9 items which we categorized by the number of instances reported (0, 1–2, and ≥ 3). Two items represented both behavioral hardship (not seeing doctor/did not take medication because of cost) and survivor/spouse job lock. Odds ratios (OR) were estimated using survey-weighted logistic regression to examine the association of caregiver employment changes with material and behavioral hardship and job lock, adjusting for cancer and sociodemographic factors.

Results

There were 183 (29.2%) survivors reporting their caregiver had an employment change. Survivors with ≥ 3 material hardships (OR = 3.13, 95%CI 1.68–5.83), who skipped doctor appointments (OR = 2.88, 95%CI 1.42–5.83), and reported job lock (OR = 2.05, 95%CI 1.24–3.39) and spousal job lock (OR = 2.19, 95%CI 1.17–4.11) had higher odds of caregiver employment changes than those without these hardships.

Conclusions

Caregiver employment changes that occur because of a cancer diagnosis are indicative of financial hardship.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

Engaging community and hospital support for maintenance of stable caregiver employment and insurance coverage during cancer may lessen survivors’ financial hardship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

The rising cost of cancer treatment underscores the need to study financial repercussions of cancer on both survivors and caregivers [1,2,3,4,5]. Cancer-related financial hardship manifests in different ways, including material and behavioral concerns [6]. Material hardship (e.g., bankruptcy and debt) arises from out of pocket cancer medical costs and lower income that may be a product of reduced work hours or lost employment due to cancer [6]. Behavioral or coping responses to financial hardship, such as skipping or delaying healthcare or medications, may be adopted to manage medical care costs while balancing increased household expenses and potentially lost wages both during and following cancer care [6]. At the same time, some survivors may face insurance worries leading to job lock, that is, the inability to leave a job due to fear of losing employer-sponsored insurance, or have a history of being denied insurance which could affect caregiver employment decisions [7].

Financial impacts of cancer extend beyond survivors to their families. Cancer caregivers are typically family members or friends who provide unpaid assistance with activities of daily living and/or health care for a cancer survivor with a severe illness [8]. Between a third to half of cancer caregivers take extended employment leave to care for their loved one with cancer, often through a combination of paid or unpaid leave [9, 10]. Other employment adjustments include going to work late and/or leaving work early, switching from full-time to part-time, and giving up work entirely [11].

Caregivers often take on the economic burden of cancer on the household. Caregivers who are employed at diagnosis provide more hours of care than unemployed caregivers [11], and this high level of caregiving involvement influences the stability of cancer caregivers’ employment [12]. Employment changes among cancer caregivers typically occur during the treatment phase [10], but can have lasting impacts in the years after treatment. Many caregivers struggle to find a pathway to workforce re-entry during cancer survivorship [11], and these employment-reentry barriers can be particularly borne by female caregivers. Changes in caregiver employment likely affect income and financial wellbeing when caregivers take on more work to pay for the costs of cancer treatment or reduce their employment to care for the cancer survivor.

The goal of this study was to examine how caregiver employment changes are associated with survivor experiences with financial hardship and health insurance. We hypothesized that increased financial hardship across material and behavioral domains, as well as insurance concerns of job lock and insurance denial would be associated with caregiver employment changes. We have previously documented that cancer survivors are at increased risk of job lock compared to siblings without cancer [13]. Furthermore, because there are actionable remedies to ameliorate job lock, we examine survivor job lock, caregiver job lock, and denial of health or life insurance separately from material and behavioral hardship domains. As financial hardship, caregiving, and employment differ by sex, we also examined the interaction of financial hardship, insurance, and sex on caregiver employment changes.

Methods

The Utah Cancer Survivor Experiences Survey was conducted in 2018 and 2019 to understand survivorship experiences among Utah cancer survivors. The survey sampled individuals living in Utah who were diagnosed with cancer between 2012 and 2017.

Sample frame and design

Eligible cancer survivors were identified using records from the Utah Cancer Registry, a population-based registry which collects and maintains information on all reportable cancer diagnoses in the state of Utah and is part of the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program. Eligible cancer survivors were age 18 or older at diagnosis, and approximately 2–5 years from the end of the year of their cancer diagnosis. That is to say, cases eligible to be sampled in 2018 were those diagnosed in 2012 through 2016, and cases eligible to be sampled in 2019 were diagnosed in 2013 through 2017. Only Utah residents at the time of diagnosis and at the time of the survey were eligible. Further, respondents must have been able to consent and to complete the questionnaire in English (2018) or in English or Spanish (2019). All SEER-reportable invasive cancer diagnoses were included, except HIV-related cases in year one and benign brain cases in year two. In situ cases were not included in either year.

To support inference of the survey results to populations who experience health disparities, sampling of subjects within the eligible population was stratified based on an area-level measure of health insurance coverage and on Hispanic ethnicity. Residents of Small Health Statistical Areas (as defined by the Utah Department of Health [14] with low health insurance coverage had a higher sampling probability so that two thirds of the sample consisted of residents in low health insurance coverage areas. Low insurance coverage was defined as areas below the median proportion of insured residents, estimated based on data from the Utah Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey [15]. In the second year of the survey, Hispanic cases had a higher sampling probability with the goal of sampling at least 150 Hispanics. Using this stratified random sample design, a total of 1,699 eligible survivors were randomly sampled for inclusion in the study (807 in 2018, and 892 in 2019).

Survey development

The survey was developed to support evaluation of cancer survivorship issues targeted in the Utah Comprehensive Cancer Prevention and Control Plan [16] and included survey measures about general health status, health care, financial impacts of cancer treatment, and caregivers. Many of the questions were identical to ones asked on the BRFSS survey, including the BRFSS module on cancer survivorship [17]. Other questions were drawn from other validated instruments [18]. The survey was administered in both paper and web format.

Measures

Caregiver employment changes outcome

We asked all survivors whether they had an informal caregiver, defined as a friend or family member who may have provided help with getting to the doctor, going to appointments, making decisions about treatment, or providing other types of care and support during or after cancer treatment. Among this group, we ascertained changes to caregiver employment by asking “Because of your cancer, its treatment, or the lasting effects of that treatment, did any of your caregivers ever take extended paid time off from work, unpaid time off, or make a change in their hours, duties, or employment status?” The outcome was operationalized as a binary variable with response indicating “yes” compared to those indicating “no,” “not sure,” and “none of my caregivers were employed while caring for me.”

Financial hardship, job lock, and insurance denial variables

Material hardship encompassed nine questions drawn from a survey conducted by the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) that adapted items from several national surveys. Items included financial coping during the prior 12 months that occurred because of medical expenses with response options “yes” versus “no” and “not sure” [18, 19]. Questions were asked about putting off major purchases, being unable to pay for necessities, taking money out of savings, spending over 10% of income on medical expenses, borrowing money, taking on credit card debt, taking out a loan or mortgage against home, thinking about filing for bankruptcy, and filing for bankruptcy. We created a composite variable to sum material responses to financial hardship, classified as 0, 1–2, and 3 or more “yes” responses. To analyze potential effect modification by sex we also analyzed material hardship response as a binary variable including participants who reported any material response compared to those who did not.

The behavioral response domain was made up of two questions, from the BRFSS questionnaire, asking about a time in the prior 12 months when the respondent delayed care due to cost or did not take medications as prescribed due to cost [17]. Finally, two items, also from the BRFSS, asked whether the survivor or their spouse/significant other experienced job lock (i.e., staying at a job because of fear of losing health insurance [13]) and a single item ascertained whether the survivor had ever been denied health or life insurance as a result of their cancer [17].

Sociodemographic and cancer variables

Sociodemographic variables obtained from self-report on the questionnaire included: race and ethnicity, marital status, educational status, employment status, and current insurance status. Sociodemographic variables obtained from cancer registry records included survivor’s current age, sex, and race and ethnicity (if not provided on questionnaire; race and ethnicity questions were not included on questionnaire in 2018), and insurance at diagnosis. Cancer variables included cancer site and month and year of diagnosis.

Survey procedures

The web instrument was created in Qualtrics. We used a mixed-mode, push-to-web methodology [20] for survivors under age 80, and a paper-only response method for survivors aged 80 or above. Respondents received a pre-notification letter, then an introductory letter approximately 7–10 days later, including a $2 pre-incentive. For survivors under 80, this letter included instructions for how to access and complete the online survey. Survivors aged 80 or above were provided with a paper survey and stamped return envelope. Up to three mailed reminders were sent to non-respondents at 7–10 days intervals after the invitation. Phone call reminders and an opportunity to respond by phone were also used for non-responders. Paper surveys were manually reviewed by study staff and were double-data-entered.

Statistical analysis and weighting

Sample weights were created to account for sample design nonresponse, and age, standardizing to the age distribution of all of UCR’s cancer survivors. We calculated summary statistics for sociodemographic and cancer factors. Descriptive statistics and chi-square tests were applied to sociodemographic, cancer, financial hardship, and insurance questions by the binary caregiver employment outcome. Two sets of survey-weighted logistic regression models were estimated for the outcome of caregiver employment changes for the financial hardship response domains (material, behavioral,) and for the insurance outcomes: first adjusting for only time since diagnosis and cancer type; second, adjusting for time since diagnosis, cancer type, age, sex, race/ethnicity, and education. Because there were minimal differences in the sets of models herein, we report only the second set of models with two exceptions for spending > 10% of income on medical expenses and taking medications as prescribed which were only significantly associated in the first set of models. We also analyzed sex for effect modification on financial hardship response domains. Stata software version 16 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX) was used for analysis.

Results

There were n = 1,002 respondents who completed the questionnaire. Response rates by ethnicity were Hispanic (36.7%), non-Hispanic white (63.1%), and all other races (36.5%). For our analysis, we limited the sample to n = 766 survivors who had previously or were currently receiving treatment. Then, we excluded n = 139 survivors who reported having no caregiver (n = 123), or did not report an answer (n = 16), which resulted in the final sample for this analysis which was N = 627.

Overall, 29.2% of survivors reported that their caregiver made an employment status change because of their cancer (Table 1). There was a smaller proportion of survivors ages ≥ 65 years (19.5%) among those who reported their caregiver had experienced employment changes compared to those who reported no change (40.0%, p < 0.01). There were significantly more Hispanics among survivors who reported caregiver employment changes (12.3%) than those who did not (4.5%, p < 0.01), and significant differences by survivor health insurance status, with a higher proportion with private insurance among survivors reporting caregiver job changes (79.2%) than among those with public insurance (71.4%, p = 0.02).

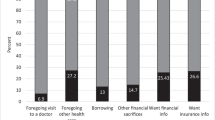

Material response to financial hardship

Compared to survivors whose caregiver maintained their employment, survivors whose caregiver had changed employment more frequently reported material financial hardship (Table 2). Significant differences in univariate comparisons were observed for putting off major purchases (25.2% vs. 12.0%), taken money out of savings (53.2% vs. 30.3%), spent more than 10% of their income on medical expenses (30.2% vs. 18.9%), borrowed money (22.3% vs. 6.3%), taken on credit card debt (29.3% vs. 12.5%), taken out a mortgage against their home or taken out a loan (10.1% vs. 1.5%), thought about filing bankruptcy (13.2% vs. 4.0%), and actually filed for bankruptcy (4.0% vs. 0.0%). Overall, 26.5% of survivors whose caregiver had changed employed reported 3 or more material hardships compared to 10.4% of those who did not report a caregiver employment change.

In multivariable models adjusted for both clinical and socioeconomic factors, each of the material hardship indicators that were significant in univariate analysis again showed significant associations, except for spending > 10% of income on medical expenses, which was only significantly associated with caregiver employment changes when adjusted for time since diagnosis and cancer type (OR 2.07, 95% CI 1.02–4.20, data not shown). The strongest associations based on OR estimates were for having borrowed money (OR 3.35, 95% CI 1.87–6.01) and for having taken out a mortgage against their home or taken out a loan (OR 6.17, 95% CI 2.19–17.37, Table 2). For the summary variable, compared to survivors reporting no material hardship, experiencing 1–2 hardships (OR 1.83, 95% CI 1.08–3.11) or 3 or more hardships (OR 3.13, 95% CI 1.68–5.83) was associated with greater odds of caregiver employment status changes.

Behavioral response to financial hardship

Behavioral financial hardship included skipping doctor appointments and medication because of cost (Table 3). Survivors who skipped doctor appointments were more likely to report their caregiver changed employment in both univariate (13.0% vs. 3.9%, p < 0.01) and multivariable analyses (OR 2.88, 95% CI 1.42–5.83), compared to survivors who had not skipped doctor appointments. Survivors who skipped medications were more likely to report their caregiver changed employment (8.6% vs. 4.2%, p = 0.03). This difference remained when adjusting for time since diagnosis and diagnosis type, with those who skipped medications reporting 2.07 higher odds of having a caregiver change jobs (95% CI 1.02–4.20, data not shown) but was no longer significant when adjusted for time since diagnosis, diagnosis type, age, sex, race/ethnicity, and education. Sex did not modify the effect of financial hardship on caregiver employment (data not shown).

Job lock and insurance denial

Job lock was measured for both cancer survivors and their spouses (Table 3). Significantly more survivors reporting personal job lock concerns had a caregiver change employment (25.1% vs. 13.1%, p < 0.01) compared to those whose caregiver had stable employment. This difference was maintained in multivariable models with those experiencing job lock themselves reporting 2.05 higher odds (95% CI 1.24–3.39) of caregiver employment change compared to survivors whose caregivers had stable employment. Among survivors reporting caregiver employment changes, 16.2% responded that their spouse experienced job lock versus 6.9% of survivors whose caregiver had stable employment (p < 0.01). In multivariable models, the difference in likelihood of spouse job lock was preserved with survivors whose spouses reported job lock having 2.19 higher odds (95% CI 1.17–4.11) of a caregiver changing jobs than those whose caregivers maintained stable employment. In addition, denial of health or life insurance due to their cancer was more common among those experiencing a caregiver employment change. No significant effects were found for job lock/insurance denial for modification by sex (Supplemental Table 1).

Discussion

Cancer care costs across the US continue to rise, placing an undue burden on many families facing cancer. While most cancer survivors have a caregiver throughout their treatment [10], neither unpaid caregiving nor opportunity costs of caregiving such as having to reduce work, lower productivity at work due to caregiving stress, or experiencing employment burnout during cancer caregiving, are factored into cancer care costs, and should be priority areas for research. Specifically, 29.2% of survivors in our sample reported changes to their caregiver’s employment, similar to other studies [21]. Survivors who reported material hardship, skipping medical care and medication due to cost, and experiencing personal or spousal job lock and health or life insurance denial had significantly higher odds of caregiver employment change. Our results indicate that caregiver employment changes may be a marker for a cancer survivor’s report of long-term financial hardship and potentially mean that studies focused solely on the financial impact on patients underestimate the cost consequences of cancer.

Material hardship demonstrates the financial tradeoffs patients make due to cancer costs, and many of these domains were associated with caregiver job changes, too. Borrowing money and mortgaging one’s home could have severe, long-term consequences on families. Even with state and federal employment protections such as the Federal Medical Leave Act (FMLA), caregivers often have limited time off to care for cancer patients. Meaning that, caregivers have to choose between maintaining employment to finance their living and caregiving expenses or prioritize their caregiving needs by reducing or changing their employment. It may also be the case that cancer caregivers who were unemployed at diagnosis may have to choose to limit their time for caregiving and other responsibilities and return to work at a time when they are needed by the cancer patient and other dependents or care recipients. Decisions related to material financial hardship have the potential for long term negative impacts on patients, caregivers, and the family members who rely on their incomes and financial stability.

Our results suggest that caregiver employment changes have a downstream effect on cancer patient health outcomes. Specifically, that cancer patients whose caregiver changed their employment were significantly more likely to skip medications and skip or delay appointments. This effect has been previously documented among cancer patients who changed or lost employment, but to our knowledge, this is the first evidence suggesting that caregiver employment changes negatively influence cancer patient treatment adherence [22]. This novel finding further justifies the need to measure caregiver and cancer patient employment status and financial hardship throughout cancer diagnosis and treatment. More research is needed to explain the effect of caregiver employment changes on patient health outcomes, but this preliminary result is concerning and merits attention.

The impact of caregiver employment changes likely extends beyond direct and indirect fiscal impacts. Financial burden is also associated with cancer survivor’s mental health and behaviors [23]. Psychological symptoms such as stress, anxiety, and depression are common among cancer caregivers [24, 25], and may contribute to or compound the impact of caregiver employment changes. For example, we found that cancer patients who had a caregiver change employment were 2–4 times more likely to report skipping doctor appointments and medications due to cost. Similarly, a recent study reported that lung cancer caregivers who had significant anxiety or depressive symptoms lost on average lost 16 hours of work per week due to the illness [12].

Job lock is common among cancer survivors due to the majority of health insurance coverage in the U.S. being employer-based [26]. We found 2.05 to 2.66 times higher odds of caregivers changing employment among survivors who experienced job lock, who had a spouse who experienced job lock, and who had been denied health or life insurance due to cancer. This is consistent with other work from our team demonstrating that cancer survivors are at increased risk of job lock compared to siblings without cancer [13]. If the direct financial implications of caregiver job changes are not enough to warrant change, the indirect influence of caregiver job changes, both during and after cancer treatment, on cancer caregiver and patient psychological wellbeing underscores a critical need to provide structures and safety nets that stabilize caregiver employment and potentially reduce cancer survivor’s financial hardship and job lock.

Utah has over 80,000 survivors of cancer [16], and several unique features related to cancer prevention and control that may have impacted our findings, including a markedly low smoking rate [27], young average age [28], and growing Hispanic population [29]. Historically, Utah boasts a very strong economy, but has one of the highest personal bankruptcy rates in the country [30]. Being uninsured and underinsured in Utah, and other states that lack or have been slow to uptake Medicaid expansion, may mean that survivors in Utah have experienced lower access to care or higher out of pocket costs than survivors with adequate health insurance coverage. Furthermore, demographically, more cancer caregivers in Utah than the general US are female and engaged in multiple care responsibilities [31, 32], including for young children and older parents/grandparents, which when combined with cancer caregiving make employment untenable.

Changes in caregiver employment may have differential and unequal implications for caregivers across the life course [33]. Specifically, young (25.5% changed vs. 10.0% did not) and middle-aged adults (55% changed vs. 50% did not) had significantly higher proportions of individuals who changed employment because of cancer than those over age 65 years (only 19.5% changed and 40% did not). While the vast majority of cancer caregivers work while providing care, young caregivers are more likely to work than their older counterparts [34], more likely to go into debt and file bankruptcy [33], and caregiving affects their career trajectories and earning potential [9]. For these reasons, young caregivers may especially benefit from interventions, including community, government, and employer supports to stabilize their employment during cancer. One challenge to engaging young caregivers in these supports is that cancer caregiving among working-aged adults is often unexpected and occurs at a time when many young caregivers have multiple caregiving roles including for young children and aging parents or grandparents [35, 36]. The impact of caregiving for a cancer patient may be detrimental to employment when young adults have yet to establish equity or financial stability that is typically gained with age. Novel interventions designed with input from young cancer caregivers that prioritize their unique needs are a high priority for future research, particularly for caregivers who assist patients with limited physical function [37].

There were limitations in the way we measured cancer caregiver employment changes. The measure we used did not consider the direction (i.e., increase or decrease in work hours) of the employment change. Because the study was based on a questionnaire administered at one time point, 2 to 5 years after cancer diagnosis, it is unknown whether caregiver employment changes occurred before or after the reported financial hardships. Further, we lack information on the age of the caregiver and on relationship status to the cancer survivor. Even after using stratified sampling to increase the proportion of Hispanics surveyed beyond their proportion in the Utah cancer survivor population, the number of respondents whose race or ethnicity was other than non-Hispanic white was too small to enable subgroup analysis by race or ethnicity.

Conclusions

The current economic value of unpaid family caregiving in the U.S. is estimated at $67 billion [38]. With the aging of the US population, it is expected that by 2050 the number of working-aged younger and middle age adults who are family caregivers will nearly double [38]. Others have commented that in the coming decades, sustainment of caregiver employment during cancer will be critical as cancer caregiving roles increasingly shift to younger, working-aged, adults, who are more likely to employed than older caregivers [9]. The present study found that caregivers frequently changed employment due to cancer. Our results document associations between cancer caregiver employment changes and material and behavioral financial hardship, job lock, and health insurance concerns during cancer. This work emphasizes the need for attention to issues of caregiver employment. Initiatives that have been proposed include policy to support employment, compensation for caregiving, and child and elder care to enhance cancer caregiver’s ability to maintain employment at pre-diagnosis levels [39].

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Utah Cancer Registry but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used with permissions for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the Utah Cancer Registry.

Code availability

The code that supports the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the authors.

References

Mariotto AB, et al. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010–2020. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(2):117–28.

Nipp RD, et al. Financial Burden in Survivors of Childhood Cancer: A Report From the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol : Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2017;35(30):3474–81.

Zafar SY, et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: a pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. Oncologist. 2013;18(4):381–90.

Banegas MP, et al. The social and economic toll of cancer survivorship: a complex web of financial sacrifice. J Cancer Survivorship : Res Pract. 2019;13(3):406–17.

Smith GL, et al. Financial Burdens of Cancer Treatment: A Systematic Review of Risk Factors and Outcomes. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw : JNCCN. 2019;17(10):1184–92.

Altice CK, et al. Financial Hardships Experienced by Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(2).

Nijboer C, et al. The role of social and psychologic resources in caregiving of cancer patients. Cancer. 2001;91(5):1029–39.

Kent EE, et al. Caring for caregivers and patients: Research and clinical priorities for informal cancer caregiving. Cancer. 2016;122(13):1987–95.

Longacre ML, Weber-Raley L, Kent EE. Cancer Caregiving While Employed: Caregiving Roles, Employment Adjustments, Employer Assistance, and Preferences for Support. J Cancer Educ. 2021;36(5):920–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-019-01674-4.

de Moor JS, et al. Employment implications of informal cancer caregiving. J Cancer Survivorship : Res Pract. 2017;11(1):48–57.

Fitch MI, Nicoll I. Returning to work after cancer: Survivors’, caregivers’, and employers’ perspectives. Psychooncology. 2019;28(4):792–8.

Mosher CE, et al. Economic and social changes among distressed family caregivers of lung cancer patients. Support Care Cancer : Off J Multinatl Assoc Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(3):819–26.

Kirchhoff AC, et al. “Job Lock” Among Long-term Survivors of Childhood Cancer: A Report From the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(5):707–11.

Small Health Statistical. In: Utah Automated Geographic Reference Center. https://gis.utah.gov/data/health/health-small-statistical-areas/. Accessed 1/11/2022

Office of Public Health Assessment: Center for Health Data and Informatics. 2021. https://opha.health.utah.gov/. Accessed 1 Jan 2022.

Utah Cancer Action Network, 2016–2020 Utah comprehensive cancer prevention and control plan. 2016. Avaialble at: https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/publications/cancer/ccc/utah_ccc_plan-508.pdf. Accessed 1/11/2022.

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Questionnaire. In: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/questionnaires/pdfques/2017_BRFSS_Pub_Ques_508_tagged.pdf. Accessed 25 June 2021.

Park ER, et al. Assessing Health Insurance Coverage Characteristics and Impact on Health Care Cost, Worry, and Access: A Report From the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1855–8.

Fair D, et al. Material, behavioral, and psychological financial hardship among survivors of childhood cancer in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer. 2021;127(17):3214–3222.

Dillman DA. The promise and challenge of pushing respondents to the web in mixed-mode surveys. In: Survey Methodology, Statistics Canada. 2017. 120–001-x (43): No 1. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/12-001-x/2017001/article/14836-eng.htm. Accessed 1/11/2022.

de Moor JS, et al. Employment implications of informal cancer caregiving. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;11(1):48–57.

Altice CK, et al. Financial Hardships Experienced by Cancer Survivors A Systematic Review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;109(2):djw205.

Jones SMW, Nguyen T, Chennupati S. Association of Financial Burden With Self-Rated and Mental Health in Older Adults With Cancer. J Aging Health. 2020;32(5–6):394–400.

Geng HM, et al. Prevalence and determinants of depression in caregivers of cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2018;97(39):e11863.

Kent EE, et al. The Characteristics of Informal Cancer Caregivers in the United States. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2019;35(4):328–32.

Rashad I, Sarpong E. Employer-provided health insurance and the incidence of job lock: a literature review and empirical test. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2008;8(6):583–91.

Map of current cigarette use among adults. In: Center for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/statesystem/cigaretteuseadult.html. Accessed 22 April 2021.

Mean age by state 2022. In: World Population Review. 2021. https://worldpopulationreview.com/state-rankings/median-age-by-state. Accessed 22 April 2021.

Krogstad J. Hispanics have accounted for more than half of total U.S. population growth since 2010. In: Pew Research Cancer. 2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/07/10/hispanics-have-accounted-for-morethan-half-of-total-u-s-population-growth-since-2010. Accessed 22 April 2021.

Bankruptcy filing trends in the United States. American Bankruptcy Institute. 2021. https://abiorg.s3.amazonaws.com/Newsroom/State_Filing_Trends/2020_TRENDS_NATIONAL.pdf. Accessed 11 Jan 2022.

2015-2019 Women in the Workforce: State of Utah. In. Department of workforce services. 2021. https://jobs.utah.gov/wi/data/library/laborforce/womeninwf.html. Accessed 26 June 2021.

Caregiving in the U.S. 2020. In: AARP Family Caregiving & The National Alliance for Caregiving. 2020. https://www.caregiving.org/caregiving-in-the-us-2020. Accessed 11 Jan 2022.

Banegas MP, et al. For Working-Age Cancer Survivors, Medical Debt And Bankruptcy Create Financial Hardships. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(1):54–61.

Finn B. Millennials: The emerging generation of family caregivers. In: AARP Public Policy Institute. 2018. https://www.aarp.org/ppi/info-2018/millennialfamily-caregiving.html. Accessed 11 Jan 2022.

Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol. 2000;55(5):469–80.

Arnett JJ. Conceptions of the transition to adulthood among emerging adults in American ethnic groups. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev. 2003;100:63–75.

Sherwood PR, et al. Predictors of employment and lost hours from work in cancer caregivers. Psychooncology. 2008;17(6):598–605.

Mudrazija S. Work-Related Opportunity Costs Of Providing Unpaid Family Care In 2013 And 2050. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(6):1003–10.

Committee on Family Caregiving for Older Adults; Board on Health Care Services; Health and Medicine Division; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Schulz R, Eden J, editors. Families Caring for an Aging America. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2016 Nov 8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK396401. Accessed 11 Jan 2022.

Funding

This study was supported by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Program of Cancer Registries, Cooperative Agreement No. NU58DP006320. The Utah Cancer Registry is also funded by the National Cancer Institute's SEER Program, Contract No. HHSN261201800016I, with additional support from the University of Utah and Huntsman Cancer Foundation. Dr. Warner is supported in part by the National Cancer Institute under award T32CA078447.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Survey design, material preparation, and data collection were performed by Morgan Millar, Sandra Edwards, Marjorie Carter, Carol Sweeney, and Anne Kirchhoff. Data analysis was performed by Echo Warner and Brian Orleans. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Echo Warner and Perla Vaca Lopez and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This study was approved by the Utah Department of Health institutional review board.

Consent to participate

Participants who completed the consent process provided free-given, informed consent to participate in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Warner, E.L., Millar, M.M., Orleans, B. et al. Cancer survivors’ financial hardship and their caregivers’ employment: results from a statewide survey. J Cancer Surviv 17, 738–747 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-022-01203-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-022-01203-1