Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study is to develop a European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Group (EORTC QLG) questionnaire that captures the full range of physical, mental, and social health-related quality of life (HRQOL) issues relevant to disease-free cancer survivors. In this phase III study, we pretested the provisional core questionnaire (QLQ-SURV111) and aimed to identify essential and optional scales.

Methods

We pretested the QLQ-SURV111 in 492 cancer survivors from 17 countries with one of 11 cancer diagnoses. We applied the EORTC QLG decision rules and employed factor analysis and item response theory (IRT) analysis to assess and, where necessary, modify the hypothesized questionnaire scales. We calculated correlations between the survivorship scales and the QLQ-C30 summary score and carried out a Delphi survey among healthcare professionals, patient representatives, and cancer researchers to distinguish between essential and optional scales.

Results

Fifty-four percent of the sample was male, mean age was 60 years, and, on average, time since completion of treatment was 3.8 years. Eleven items were excluded, resulting in the QLQ-SURV100, with 12 functional and 9 symptom scales, a symptom checklist, 4 single items, and 10 conditional items. The essential survivorship scales consist of 73 items.

Conclusions

The QLQ-SURV100 has been developed to assess comprehensively the HRQOL of disease-free cancer survivors. It includes essential and optional scales and will be validated further in an international phase IV study.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

The availability of this questionnaire will facilitate a standardized and robust assessment of the HRQOL of disease-free cancer survivors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Given the steady increase in the number of people who are living beyond cancer (cancer survivors), attributed to early detection, improved treatments, and the ageing of the population [1], there is a growing interest in evaluating their health-related quality of life (HRQOL) [2]. Increasingly, clinical trials and comparative effectiveness studies are being designed to include long-term follow-up to assess, in addition to survival, HRQOL, and late effects of treatment. In order to integrate HRQOL in such studies, the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Group (QLG) has embarked on a project with the primary objective to develop an HRQOL assessment strategy that captures the full range of issues relevant to disease-free cancer survivors, both in general and for specific cancer sites [3].

The conceptual framework we employed for the development of our assessment strategy follows the World Health Organization (WHO) definition of health, dating from 1948, combined with the Medical Outcomes study (MOS) framework [4]. In this framework, we recognize three key dimensions of health: physical, mental, and social. Our survivorship measurement strategy is intended to be used among cancer survivors, treated with curative intent, who are at least 1 year post-treatment (with the exception of maintenance treatment), and believed to be disease-free (i.e. have no evidence of active disease). It includes a cancer survivorship core questionnaire that is intended for a wide range of cancer survivor populations, which can be used as a stand-alone questionnaire or can be supplemented with a cancer site-specific (survivorship) module [3] and/or selected items from the EORTC QLG item library [5].

Our questionnaires are targeted at disease-free survivors who are 1 year or more post-treatment, as we previously found evidence that both physical and psychosocial health issues tend to stabilize after this period [3]. This also marks the end of the early survivorship period in which patients often have dealt with the initial emotions surrounding their diagnosis and acute treatment-related symptoms, are confronted with the more chronic problems associated with their disease and its treatment, and might be for many of them the beginning of finding meaning in their experience of having had cancer.

We have previously reported on the identification of the issues relevant for disease-free cancer survivors [3], which is the first phase in the development of the EORTC QLG’s four-phase process of questionnaire development [6]. In the second phase, these issues were converted into questionnaire items. In this paper, we present the results of phase III of the EORTC questionnaire development in which we pre-tested and further developed the preliminary EORTC QOL cancer survivorship core questionnaire, the QLQ-SURV111. To meet the needs for a shorter version of the survivorship questionnaire that is suitable for evaluating long-term HRQOL outcomes in clinical trials and routine clinical assessments, we also identified essential scales which always need to be included when assessing HRQOL in cancer survivors and optional scales which can be added to provide a more complete picture of the HRQOL of cancer survivors.

Methods

Preliminary development of the QLQ-SURV111

Phase I of The development of an EORTC QOL cancer survivorship questionnaire consisted of two sub-phases: phases 1a and 1b. In phase 1a, we generated an exhaustive list of all HRQOL issues relevant to disease-free cancer survivors irrespective of their cancer diagnosis and irrespective of whether they were generic issues or specific to particular cancer diagnoses. In the process of compiling the list, two sources were consulted: the literature (134 studies) and cancer survivors (N = 117). In phase 1b, the resulting list of 267 issues was rated for relevance by 458 cancer survivors and 89 healthcare providers. This resulted in a list of 116 generic survivorship issues, of which 2 were sex-specific [3].

In phase II, we deleted or rephrased issues of the generic survivorship issue list that were rated as redundant, unclear, or upsetting or did not fit in our conceptual framework. We also carried out preliminary factor analyses to identify redundant issues. The remaining issues were operationalized into questionnaire items using the four-point Likert-type response scale and 1-week or 4-week time frame as typically used for EORTC HRQOL questionnaires. The 1-week recall period is for symptoms that, if present, typically will have occurred in the past week, like feeling tired or having swelling in legs, ankles, or feet. This 1-week time frame is more sensitive to change than longer recall periods [7]. However, it is less suitable for sexual issues, as many people do not engage in sexual activities on a weekly basis. Therefore, the EORTC QLG has chosen during the development of its questionnaire to apply a 4-week time frame for all issues related to sexual functioning or problems [8, 9]. Two additional reference points were added to accommodate certain questions: “Since the diagnosis and treatment of your cancer” and “Because of your experience with cancer”.

Rather than developing new items, if available, relevant items with appropriate content were selected from the EORTC QLG item library [5] or were based on items from existing patient-reported outcome measures. This resulted in a provisional survivorship core questionnaire, the QLQ-SURV111 (see Table 1). The QLQ-SURV111 consists of 111 items and retained 25 of the original items from the QLQ-C30 (excluding only those items that assessed acute symptoms), 9 additional items from the EORTC Computer Adaptive Test (CAT) item bank [10], and a range of generic survivorship issues (i.e. issues not specific to a given cancer diagnosis). The QLQ-SURV111 was translated into Bengali, Portuguese (Brazil), Danish, Dutch, French, German, Greek, Hebrew, Icelandic, Italian, Norwegian, Polish, Spanish, and Swedish according to standard EORTC procedures [11]. The phase I and II development process reports and paper [3] were peer-reviewed and formally approved by the EORTC QLG Protocol and Module Development Committee (PMDC) before the start of phase III.

Study sample

We recruited cancer survivors from hospitals and cancer registries from four geographic regions: English-speaking countries (UK, Australia), Northern Europe (Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Iceland, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden), Southern Europe (Cyprus, France, Greece, Israel, Italy, Spain), and outside Europe (Brazil, India). Eligible patients were those aged 18 years or older at the time of diagnosis who had sufficient command of their native language and did not have serious psychological or cognitive problems that would interfere with their ability to take part in the study. We recruited survivors with a range of cancer diagnoses, selected on the basis of their prevalence and/or survival rates. These included 11 diagnoses: breast, colorectal, prostate, bladder, gynaecological (ovarian, cervical, and endometrial), head and neck, lung, and testicular cancer, lymphoma, melanoma, and glioma. Eligible patients had completed their treatment with curative intent (both primary treatment and treatment of recurrent disease) 1 to 10 years earlier and were disease-free (i.e. no evidence of disease). They could be receiving maintenance therapies (e.g. hormonal treatment for primary breast cancer). Although low-grade glioma patients were not treated with curative intent and were not disease-free, they were included since they can have a very long period of survival (up to 16 years), and in the relatively long period between primary treatment and recurrence, they often do not receive any treatment [12, 13].

We employed purposive sampling to ensure an approximately equal distribution of survivors across diagnoses and time since treatment categories [6]. We distinguished four different time periods since end of last treatment (1 to < 2 years/2 to < 3 years/3 to < 5 years/5 to 10 years) and included all 11 diagnostic groups mentioned above. Based on the cancer diagnosis and time since of end of treatment, a recruitment matrix was created consisting of 11 by 4 cells. We aimed to include five participants per cell. In addition, the sample was stratified by geographical region. For breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer, our goal was to include 20 survivors per cell (80, in total, per tumour type), as we were simultaneously developing cancer site-specific survivorship modules for these survivor populations. We will report on the development of these modules in subsequent papers. In total, our goal was to recruit 400 survivors into the study.

Procedures

Eligible survivors were given written information about the objectives and procedures of the study and were invited to participate in accordance with ethical and governance requirements of each participating centre. Ethical approval was gained at each site. Basic sociodemographic data collected at study entry included age, sex, education, employment status, and living arrangement. Clinical data collected included primary diagnosis, stage of disease, type of treatment, date of diagnosis, date of start and completion of primary treatment, previous disease recurrence(s), date of completion of treatment for last recurrence, and comorbidity as assessed by the Charlson Index [14].

All participants completed the QLQ-SURV111 and were asked to indicate for each item whether they would include it in a survivorship questionnaire (response options yes/no). If participants commented on any items while they completed the questionnaire or had problems understanding any items, this was noted by the interviewer for further analyses. After completing the questionnaire, the participants were asked to answer a series of “debriefing” questions to determine if any of the candidate items of the QLQ-SURV111 were too difficult, confusing, upsetting, or redundant, or if important issues were missing.

Paper versions of the questionnaires were completed: (1) in a face-to-face interview setting; (2) in a telephone interview setting whereby the respondent had the questionnaire at his or her disposal; or (3) by mail, without a subsequent interview. Following the translation procedures of the EORTC [11], our goal was to have at least 10 questionnaires per translation completed in an interview setting in order to inquire in detail about the comprehensibility of each of the translations. The telephone setting was an option for survivors who preferred not to travel to the hospital. We included the subsample of survivors who completed the questionnaire by mail without an interview to ensure that we had sufficient cases for the requisite psychometric analyses.

Criteria for item selection based on descriptive statistics

The questionnaire data were analysed using descriptive statistics according to the EORTC guidelines [6]: items were retained when (1) at least 60% of the sample had indicated that the item should be included in the next version of the QLQ-SURV111 and (2) the observed scale range of the item should be greater than 2 points. The remaining EORTC criteria were applied per subgroup: (3) mean item score > 1.5 (on a four-point scale ranging from 1 to 4, with 1 being “not at all” and 4 “very much”); (4) prevalence of the item (score of 2 or greater) > 30%; and (5) item completed by at least 95% of the respondents. Subgroups were as follows: time since last treatment (1 to < 2 years; 2 to < 3 years; 3 to < 5 years; 5 to 10 years); tumour stage at diagnosis (I; II; III; IV); treatment (no chemotherapy (CT) no radiotherapy (RT); RT only; CT only; RT + CT); hormonal therapy (current hormonal therapy (HT); HT past and current; never HT); age (younger than 40; 40 to < 50; 50 to < 60; 60 to < 70; 70 +); and sex (male; female). If the criteria were met in at least one of these subgroups, items were retained to ensure that all items relevant for each of these subgroups would be included in the final questionnaire.

Qualitative data analyses

To investigate whether there were any significant concerns expressed by patients about the questionnaire items (e.g. items that were upsetting or ambiguous), all debriefing interviews and remarks on the questionnaires were analysed using QSR NVivo 10 software [15]. Each entry was classified according to cancer site, language, country, and educational level of the respondent. For details regarding the qualitative data analyses, see the technical appendix in Online Resource 1.

Proposed scale structure

Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were conducted in Mplus 6.1 [16] to examine the hypothesized scales (see Table 1) based on our three dimensional measurement model [3]. The conditional items (S62, S87, S88, S101, S102, S105, and S106) were excluded from these analyses. Each hypothesized scale was modelled in a separate factor model, as our sample was not large enough to evaluate all elements of our complete measurement model simultaneously. For the scales for which a factor model could not be fitted due to limited degrees of freedom (df), Cronbach’s alpha or Spearman’s r were calculated. In the cases where our hypothesized factor model did not fit well and we did not have an alternative hypothesis, we investigated the scale structure using exploratory factor analysis (EFA) in Mplus 6.1 [16] or correlational analyses in case of insufficient df. To test goodness of fit of the CFA and EFA models, the comparative fit index (CFI) and the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) were used. For both, values ≥ 0.97 indicate a good fit, between 0.95 and 0.97 an acceptable fit, and below 0.95 a poor fit [17]. For details of these analyses, see Online Resource 1.

Preliminary item reduction using item response theory (IRT) modelling

For the proposed scales of the QLQ-SURV111 consisting of five items or more, we applied IRT modelling to exclude redundant items, i.e. multiple items covering the same trait level or items that do not discriminate well between various trait levels. The IRT analysis was only carried out for the scales for which the CFA showed a good fit (unidimensionality). When this condition is fulfilled, items are expected only to be correlated because any covariation between them can be ascribed to their relationship with the latent trait, and when controlling for the latent trait, all pairs of items within a domain should be uncorrelated, and consequently the residual correlation should be below 0.2 [18]. To evaluate the scales of the QLQ-SURV111, we took the assessed trait levels of each of the response categories into account, using category threshold parameters (b). Items with high thresholds provide most information for respondents who score high on a particular trait, and items with low thresholds provide most information for respondents who score low on a particular trait. In case the thresholds are disordered (i.e. the b2 is lower than b1), an item is weak, as it is not able to discriminate between different trait levels. The item discrimination parameter a informs how well an item is able to discriminate between various trait levels. For additional details regarding the IRT analyses, see Online Resource 1.

Essential and optional scales

To meet the needs for a shorter version of the survivorship questionnaire that is suitable for evaluating long-term HRQOL outcomes in clinical trials, we made a distinction between “essential” and “optional scales” of the QLQ-SURV. In the clinical trial context or routine clinical settings with repeated assessments over time, the measurement strategy would be to always include the essential scales and to have the optional scales available, if deemed useful. The full length questionnaire, including both the essential and optional scales, would be more suitable for use in observational/epidemiologic and intervention studies aimed at identifying and/or improving the long-term physical and psychosocial problems of cancer survivors or when specific populations are targeted like young survivors.

As the QLQ-C30 was primarily designed to evaluate HRQOL outcomes in clinical trials, we have based our selection of essential scales of the QLQ-SURV on their correspondence with the QLQ-C30 and its underlying constructs. Correspondence was evaluated by matching QLQ-SURV scales to the QLQ C30 dimensions based on degree of overlap in content between items in both questionnaires. Also scales that correlated 0.5 or higher with the QLQ C30 summary score [19] were added as essential survivorship scales, as they measure HRQOL constructs that are of importance to cancer survivors and are related to the HRQOL construct of the QLQ-C30 (for details, see Online Resource 1).

To validate our selection of essential versus optional scales, we conducted a Delphi survey [20,21,22] using DelphiManager software[23] with 3 groups of experts (patients, healthcare professionals (HCPs), and HRQOL researchers). In three consecutive rounds, these expert groups were asked to rate the importance of the scales of the QLQ SURV that had not already been identified as essential based on their correspondence with QLQ-C30 scales and/or correlation with the QLQ-C30 summary score [19]. Our goal was to include 23 experts per group, as Akins et al. [24] have shown that a group of 23 individuals with the same type of expertise can arrive at stable outcomes (for further details, see Online Resource 1).

The final set of essential QLQ-SURV scales consisted of scales that were originally C30 scales, whose item content by definition corresponded with that of QLQ-C30 items/scales, scales that correlated relatively highly (i.e. 0.5 or higher) with the QLQ-C30 summary score, and scales that were defined as essential based on expert consensus in the Delphi survey.

The essential and optional scales were grouped by time frame: i.e. each time frame starts with the essential scales in this time frame and ends with the optional scales in the same time frame. In addition, to rule out item-order effects between the QLQ-C30 and the QLQ-SURV, the order of the items existing in both questionnaires was placed in the same order [25, 26].

Pretesting the updated QLQ-SURV

The items that were reformulated and the updated order of items were pretested in semi-structured interviews held in the Netherlands, Belgium, the UK, Croatia, and Spain. We aimed to include 55 to 110 interviews, in total. The aim of this pretesting was to determine if any of the rephrased items were too difficult, confusing, or upsetting and whether the updated order of the questionnaire was acceptable.

Results

Survivor characteristics

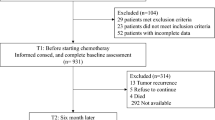

Between January 2018 and April 2019, 515 cancer survivors from 27 centres in 17 countries completed the questionnaires, of whom 388 did so in a face-to-face setting or by telephone with an interviewer being present and 127 did so by mail. Twenty-three questionnaires were excluded because the survivors did not meet the inclusion criteria.

Table 2 reports the demographics and disease and treatment characteristics of the survivor sample (N = 492). The mean age was 60 years (range 22 to 89 years), 46% were female, and mean time since last treatment was 3.8 years (SD 2.39 years). The median time needed to complete the questionnaire without the cancer site-specific modules and the debriefing questionnaires was 25 min.

Item selection based on descriptive statistics

All items of the provisional questionnaire were considered to be relevant and worthy of inclusion in the definitive version by 84 to 97% of the respondents. For all items, the range of responses was 3 response categories. Missing data analysis at the individual item level indicated that between 7 and 15% of the items related to sexuality were missing. As sexuality is an important aspect of HRQOL and missing responses to sensitive questions like sexuality are common with existing EORTC modules [27, 28], we did not exclude them from the questionnaire. For all other items, 5% or less had missing responses. The only exceptions were three conditional items about fertility (S62), loss of income (S92), and lack of support of colleagues (S93). However, we believe that the missingness for these items was primarily related to the instructions used, which we have subsequently refined (e.g. for item S62, fertility, we have added the instruction “If you did/do not want to have (more) children, please select “not applicable”.

The items regarding taking a short walk (S7), help with self-care (S9), nail problems (S26), and thin skin (S28) did not reach the thresholds of the decision rules for inclusion (mean > 1.5 and prevalence ratio > 30%) in any of the relevant subgroups. Since item S7 and S9 were QLQ-C30 items, they were evaluated further in the IRT analyses before taking any decisions about in- or exclusion. Items S26 and S28 were excluded from the QLQ-SURV.

Qualitative data analysis

Less than 3% of the sample considered the questionnaire too lengthy. In general, we detected relatively few problems with the questionnaire. Based on the qualitative analyses we updated 11 items (see Table 1 of Online Resource 1 for the updated items). We rephrased the introductory text of items S69 and S70 from “Has your physical condition or medical treatment with your family life/ social activities to “Have cancer-related physical problems…”, as participants thought these items referred to their active treatment period. Therefore, these items became too similar to S76 “Have cancer-related physical problems interfered with your life?” For that reason, we deleted the more generic item S76. The items relating to sexual issues were considered too personal by approximately 6% of the respondents. However, given the sensitive nature of sexuality for many people, we considered this acceptable and chose to retain these items in the QLQ-SURV. Details regarding the updated items can be found in Online Resource 1.

Proposed scale structure

For the majority of scales, we first tested a one-factor model (see Table 1 for scales and model fit results). Based on these findings and further modelling, (1) the health awareness scale was converted into two scales: symptom awareness and positive health behaviour change; (2) posttraumatic growth was divided into three scales: positive social functioning, positive life outlook, and positive impact on behaviour towards others; (3) social functioning negative was split into two scales and one single item: social interference, social isolation, and treated differently; and (4) the items assessing sexuality scale were divided into a sexual problems and a sexual functioning scale. Details of these analyses can be found in Online Resource 1 including the factor loadings of the items of the scales, Cronbach’s alpha and Pearson’s r.

As the symptoms assessed by items S19, S20, S22-S25, S27, and S29-S37 can be caused by multiple treatments and also because different types of chemotherapy can result in different constellations of symptoms, we had no clear hypotheses about the factor structure underlying these symptoms. Therefore, we carried out EFA to investigate whether symptoms tended to cluster. As the results of the EFA were not interpretable (for details, see Online Resource 1), we decided to treat this set of 15 symptoms as a simple, additive checklist. The checklist can be used to see which of chronic physical side effects are present, and when they are present to see how severe they are. The total score of the symptom checklist will give an indication of symptom burden. A symptom checklist seemed more appropriate than a psychometrically coherent subscale, because we could not assume that items within these factors correlated strongly with one another due to a common cause, which is the underlying assumption in factor analyses [29,30,31,32].

Preliminary item reduction using IRT modelling

The scales assessing physical functioning, fatigue, body image, cognitive functioning, emotional functioning, and health distress consisted of five items or more and were unidimensional, with residual correlations well below 0.2, and therefore met the criteria to carry out IRT analyses.

Table 4 in Online Resource 1 shows the parameter estimates from the IRT modelling for the six QLQ-SURV111 scales and the result section of Online Resource 1 explains the findings of the IRT analyses in more detail.

Physical functioning scale

IRT analyses (see Online Resource 1 for further details, including the parameter estimates, the category response curves, and the information curves) showed that items S7 (trouble taking a short walk) and S8 (stay in bed or chair), both originating from the QLQ-C30, provide most information for survivors who score poorly on physical functioning, that item S9 (help with eating, dressing, etc.) was weak, and that items S8 and S9 were the least discriminative items of the physical functioning scales. Items S1 and S6 and items S2, S3, and S4 covered the same levels of physical functioning. The IRT analyses indicated further that item S7 was highly informative for poor physical functioning. Since, from a clinical perspective, information about a survivor’s poor physical functioning is very relevant, we decided to retain this item in the survivorship questionnaire. Combining the results from the IRT analysis with the percentage of missing responses, the percentage of respondents who indicated that they would include the items in the questionnaire, and the number of comments in the debriefing interview led to the retention of items S2, S3, S5, S6, and S7. Items S8 and S9 did not appear to provide clear information on the level of physical functioning and therefore will not be used to calculate the physical functioning level in survivors. We will include these two items as optional in the QLQ-SURV to still be able to calculate physical functioning as assessed by the QLQ-C30. In phase IV, the international field study, we will investigate in a larger sample if these two items indeed should be excluded in the assessment of physical functioning in survivors.

Fatigue

The parameter estimates of the fatigue scale are presented in Online Resource 1. As item S14 (sudden fatigue) was the least discriminative item and targeted levels of fatigue already assessed by the other items, we have excluded it from the QLQ-SURV.

Body image

Items S38 (feeling unattractive), S42 (feeling embarrassed), and especially S41 (cannot trust body) were the least discriminative items (see Online Resource 1). Further, items S38 and S42 items appeared to cover a smaller bandwidth of the trait body image, and in addition, items S38 and S41 were considered difficult to understand or unnecessary. Therefore, we retained only items S39 (feeling older than age) and S40 (dissatisfied with appearance) to assess body image.

Cognitive functioning

Item S45 (performing two tasks simultaneously) showed the lowest discriminative value compared to the other cognitive items that we added to the two-item cognitive functioning scale of the QLQ-C30 (see Online Resource 1). In addition, this item targets levels of cognitive functioning already assessed by the other items. Therefore, this item was excluded.

Emotional functioning

Item S55 (need for psychological help) had the lowest discriminative value and was a weak item as can be seen in Online Resource 1. For these reasons, S55 was excluded.

Health distress

Items S56–S58 did not discriminate well on the latent trait health distress (see Online Resource 1). This suggests that fear of late effects (S56), fear for cancer among family members (S57), and fear of dying (S58) are not assessing the same construct as the other three items assessing fear of cancer for oneself (S59 and S60) and fear for own health (S61). Further inspection of item S56 “Have you worried about your treatment causing (future) health problems?” and the qualitative analyses showed that this item needed to be reworded, as survivors are no longer under active treatment. Therefore, it was rephrased to read: “Have you worried that your previous cancer treatment may cause (more) health problems in the future?” We have added this rephrased item and the item about dying (S58) to the Negative Health Outlook scale, as it seemed more appropriate there. In phase IV, we will be able to test whether this was appropriate. Fear about cancer in family members will be scored as a single item scale.

Resulting EORTC survivorship core questionnaire (QLQ-SURV100)

After deletion of the items whose prevalence was very low (S28 and S26) and/or were redundant (S1, S4, S14, S38, S41, S42, S45, S55, and S76), 100 items remained. Some of the items were rephrased and instructions for conditional items were added based on qualitative and missing data analyses. This cancer survivorship core questionnaire (QLQ-SURV100) consists of 13 functional scales assessing physical functioning (5 + 2 optional items to assess QLQ-C30 physical functioning), body image (2), cognitive functioning (4), emotional functioning (7), symptom awareness (2), positive health behaviour change (2), positive life outlook (4), positive impact on behaviour towards others (2), positive social functioning (2), work (4), role functioning (3), sexual functioning (2), and global quality of life (2); 9 symptom scales assessing fatigue (4), sleep problems (4), pain (2), health distress (3), negative health outlook (7), social interference (2), social isolation (2), sexual problems (2), and sexual problems when sexually active (2), a symptom checklist of chronic side effects of treatment (17); and 12 single items assessing financial difficulties, loss of income, problems (insurances, loans, and mortgages), deeper meaning, fertility, partner relation stronger, sexual pleasure, sexual problems (female), sexual problems (male), treated differently, worry impact of cancer on children, and risk of cancer in family members. Of these 100 items, 14 are conditional (see Table 3).

Essential and optional scales

Table 4 presents the correlation between the survivorship scales and the QLQ-C30 summary score. The symptom checklist, negative health outlook, work, body image, and health distress scales all correlated 0.5 or higher with the QLQ-C30 sum score. Together with financial impact and global health status, the scales that are included both in the QLQ-C30 and the SURV100, these scales form the essential scales of the QLQ-SURV100. In total, these scales comprise 67 items.

In total, 113 experts participated in the Delphi survey: 34 patient representatives, 43 healthcare professionals, and 36 researchers. Ninety-three percent of the experts participated in round 2 and 91% in round 3. Based on the ratings of the experts, loss of income; symptom awareness; problems with insurances, loans, and mortgages; and social isolation were added to the essential scales (see Table 3 for an overview of the items included in the essential scales), bringing the total number of items included in the essential scales to 73. More details about the selection of essential scales are reported in Online Resource 1.

Pretesting the updated QLQ-SURV100

In total, 76 survivors completed the semi-structured interview. The interviews indicated that the revised item ordering is acceptable and that there were no issues with the updated items. However, respondents did indicate that the instruction at the start of the questionnaire needed to be improved to draw their attention to the fact that the questionnaire consists of multiple time frames. Finally, because many respondents spontaneously wrote comments at the end of the questionnaire, we have decided to include an open-ended question that offers respondents the opportunity to provide additional information (e.g. about how their HRQOL has also been impacted by other life events, like ageing, other diseases, etc.).

An overview of all major changes to the items and scales of the QLQ-SURV111 can be found in Online Resource 2.

Discussion

The QLQ-SURV100 was developed, according to the rigorous standards of the EORTC [6] and based on a conceptual framework including all aspects of HRQOL, to comprehensively assess the HRQOL of disease-free cancer survivors at least 1 year after completion of treatment with curative intent. This core questionnaire can be used as a stand-alone questionnaire or in combination with cancer site-specific (survivorship) modules or items from the EORTC item library. Although a questionnaire with 100 items is quite long, only 1.4% of the survivors in this phase III study indicated that they felt that the questionnaire was too long. In many studies, different questionnaires are combined (e.g. HRQOL, symptoms, fatigue, work or relationship issues, positive growth after cancer) that often add up to much more than 100 items. As the QLQ-SURV100 is designed to be comprehensive, in principle, no additional questionnaires, except for cancer site-specific modules or items and questionnaires that need to be included in clinical trials for regulatory requirements, are necessary to assess HRQOL. Further, we assume that, in most studies and clinical practice, the HRQOL of survivors who are 1 year or longer after treatment completion will not be assessed as frequently as in patients who are still in in the active treatment phase. Only few long-term trials collect follow-up data more frequently than once a year [33].

Nevertheless, to accommodate the request from researchers in the field to develop a shorter questionnaire, we have made a distinction between essential and optional scales. The essential survivorship scales are those scales that measure the same HRQOL construct as the QLQ-C30 and the scales that were regarded as essential by patient representatives, healthcare professionals, and cancer researchers. As the narrower QLQ-C30 HRQOL construct has been designed to evaluate HRQOL outcomes in clinical trials, the 73-items making up the essential survivorship scales will be suitable to evaluate the long-term HRQOL outcomes in clinical trials. The other scales will be optional and will provide, in combination with the essential scales, a more complete picture of the HRQOL of cancer survivors.

In contrast to the HRQOL questionnaires designed for cancer patients under active treatment such as the QLQ-C30 [34] and the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Scale (FACT-G) [35], the QLQ-SURV100 does not assess acute treatment-related symptoms (e.g. vomiting or diarrhoea). Moreover, scales that are particularly relevant for survivors like fatigue, physical functioning, and emotional functioning are extended to assess these functional domain and symptoms more precisely and at a level that is relevant for disease-free survivors. In addition, the QLQ-SURV100 includes scales that address typical survivorship issues like fear of recurrence, post-traumatic growth, and long-term side effects of treatment.

Compared to the existing questionnaires that have been developed for (long-term) cancer survivors like the Cancer Problems in Living Scale (CPILS) [36], Impact of Cancer (IOC/IOCv2) [37,38,39], Long-Term Quality of Life (LTQL) [40, 41], Quality of Life in Adult Cancer Survivors (QLACS) [42, 43], Brief Cancer Impact Assessment (BCIA) [44, 45], Quality of Life Cancer Survivors (QoL-CS) [46], and Satisfaction with Life Domains Scale for Cancer (SLDS-C) [47]), the QLQ-SURV100 has the advantage that it has been developed in multiple cancer survivor populations (11 different tumour types and 17 different countries) following the rigorous guidelines for questionnaire development of the EORTC QLG [6]. Next to the psychological and social aspects of having had cancer, our questionnaire also addresses specifically the longer-term physical aspects of having had cancer, which reflects the multidimensional aspect of HRQOL [48] and is in line with the EORTC QLG approach. Further, our questionnaire maps all functional domains relevant for survivors unidimensionally. Moreover, it has the advantage that it can be supplemented with compatible cancer-site specific modules, which facilitates the assessment of both generic and condition-specific health issues. Finally, because all functional scales of the QLQ-C30 and most of the symptom scales are also included in the QLQ-SURV100, it is possible to conduct longitudinal studies with a combination of both instruments. Patients can complete the QLQ-C30 from diagnosis and during treatment, and then after a year switch to completing the QLQ-SURV100, while the continuity in measuring the same scales is guaranteed.

HRQOL and other types of patient-reported outcomes are now increasingly being recognized by international health policy and regulatory authorities [49, 50] and patients [51, 52] as pivotal outcomes [48] in cancer research, complementing the more traditional outcomes and having the potential to inform clinical decision making, pharmaceutical labelling claims, product reimbursement, and healthcare policy [53]. PRO measures (PROMs) are of particular importance in clinical trials aimed at improving (long-term) HRQOL in cancer patients with curable disease. Moreover, because of the improvement in cancer survival, a large group of patients is experiencing extended post-treatment periods without recurrent disease, making it more important to add HRQOL as primary outcome to disease-free survival and overall survival to assess treatment effectiveness [54] and also feasible because of the increased number of patients available for long-term follow-up [33]. The value of long-term follow-up has become apparent from trials showing that some important clinical effects appear only 10 or even 20 years after treatment has been delivered [33]. To be able to inform important clinical decisions based on HRQOL in clinical trials, it is fundamental that these PROMs are of high quality [51, 53] and developed in a rigorous manner [6] including all HRQOL domains as is the case for the QLQ-SURV100.

Because our measure is comprehensive, it is also suitable to assess HRQOL in non-pharmacological trials aimed at improving HRQOL, psychological, and/or physical functioning in cancer survivors [55,56,57], in observational population-wide studies in cancer survivors to investigate the impact of cancer on HRQOL [58, 59] or to evaluate the effectiveness of survivorship programs [60].

In conclusion, we have developed a core questionnaire to assess HRQOL of disease-free cancer survivors, which consists of essential scales that form a core measure for evaluating HRQOL in clinical trials and optional scales that can be used to generate a more comprehensive picture of the overall HRQOL of cancer survivors or when specific populations are targeted (e.g. younger survivors). In the next phase of our work, the international field test (phase IV), we will evaluate the proposed scale structure more rigorously by confirming the provisional scale structure as reported here in a new sample of 1600 survivors, assessing the reliability of the scales by means of test–retest stability, and assessing the validity of the scales using known-groups validity testing. We also intend to generate IRT scoring algorithms, in addition to the more traditional sum scores for the questionnaire scales.

Availability of data and material

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Division of Psychosocial Research and Epidemiology of the Netherlands Cancer Institute (contact person: L.V. van de Poll-Franse), but restrictions apply to the availability of these data due to an agreement between the Netherlands Cancer Institute and the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Group, and so they are not publicly available. Data are available pending approval of both the Netherlands Cancer Institute and the EORTC.

The QLQ-SURV100 can be requested on the website of the EORTC QLG: EORTC Quality of Life Website https://qol.eortc.org/quality-of-life-group/.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Change history

11 March 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-022-01199-8

References

Lagergren P, Schandl A, Aaronson NK, Adami HO, de Lorenzo F, Denis L, et al. Cancer survivorship: an integral part of Europe’s research agenda. Mol Oncol. 2019;13(3):624–35. https://doi.org/10.1002/1878-0261.12428.

Ayanian JZ, Jacobsen PB. Enhancing research on cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(32):5149–53. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2006.06.7207.

Van Leeuwen M, Husson O, Alberti P, Arraras JI, Chinot OL, Costantini A, et al. Understanding the quality of life (QOL) issues in survivors of cancer: towards the development of an EORTC QOL cancer survivorship questionnaire. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16(1):114. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-018-0920-0.

Stewart AL, Ware JE, Jr. Measuring functioning and well-being: the medical outcomes study approach. Durham and London: Duke University Press; 1992.

Kulis D, Bottomley A, Whittaker C, van de Poll-Franse LV, Darlington A, Holzner B, et al. The Use of The Eortc item library to supplement Eortc quality of life instruments. Value Health. 2017;20(9):A775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2017.08.2236.

Johnson C, Aaronson N, Blazeby JM, Bottomley A, Fayers P, Koller M, et al. Guidelines for developing questionnaire modules. EORTC Quality of Life Group; 2011.

Keller SD, Bayliss MS, Ware JE Jr, Hsu MA, Damiano AM, Goss TF. Comparison of responses to SF-36 Health Survey questions with one-week and four-week recall periods. Health Serv Res. 1997;32(3):367–84.

Ueda P, Mercer CH, Ghaznavi C, Herbenick D. Trends in frequency of sexual activity and number of sexual partners among adults aged 18 to 44 years in the US, 2000–2018. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(6):e203833-e. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3833.

Karraker A, DeLamater J, Schwartz CR. Sexual frequency decline from midlife to later life. J Gerontol: Ser B. 2011;66B(4):502–12. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbr058.

Petersen MA, Aaronson NK, Arraras JI, Chie WC, Conroy T, Costantini A, et al. The EORTC CAT Core-The computer adaptive version of the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire. Eur J Cancer. 2018;100:8–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2018.04.016.

Kuliś D, Bottomley A, Velikova G, Greimel E, Koller M, Group obotEQoL. EORTC quality of life Group translation procedure. EORTC Quality of Life Group; 2017.

Kumthekar P, Raizer J, Singh S. Low-grade glioma. Cancer Treat Res. 2015;163:75–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-12048-5_5.

Brito C, Azevedo A, Esteves S, Marques AR, Martins C, Costa I, et al. Clinical insights gained by refining the 2016 WHO classification of diffuse gliomas with: EGFR amplification, TERT mutations, PTEN deletion and MGMT methylation. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):968. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-019-6177-0.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83.

NVivo qualitative data analysis Software. 10 ed: QSR International Pty Ltd.; 2012.

Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus. 5.0 ed 2007.

Schermelleh-Engel K, Moosbrugger H, Müller H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods Psychol Res Online. 2003;8(2):23–74.

Bjorner JB, Kosinski M, Ware JE Jr. Calibration of an item pool for assessing the burden of headaches: an application of item response theory to the headache impact test (HIT). Qual Life Res. 2003;12(8):913–33.

Giesinger JM, Kieffer JM, Fayers PM, Groenvold M, Petersen MA, Scott NW, et al. Replication and validation of higher order models demonstrated that a summary score for the EORTC QLQ-C30 is robust. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;69:79–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.08.007.

Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32(4):1008–15.

Hsu C-C, Sandford BA. The Delphi technique: making sense of consensus. Pract. Assess. Res. Evaluation. 2007;12(1).

Keeney S, Hasson F, McKenna H. Consulting the oracle: ten lessons from using the Delphi technique in nursing research. J Adv Nurs. 2006;53(2):205–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03716.x.

COMET. DelphiManager. COMET; 2016.

Akins RB, Tolson H, Cole BR. Stability of response characteristics of a Delphi panel: application of bootstrap data expansion. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5:37. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-5-37.

Knowles ES, Byers B. Reliability shifts in measurement reactivity: driven by content engagement or self-engagement? J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;70(5):1080–90. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.5.1080.

Franke GH. “The whole is more than the sum of its parts”: The effects of grouping and randomizing items on the reliability and validity of questionnaires. Eur J Psychol Assess. 1997;13(2):67–74. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759.13.2.67.

Van de Poll-Franse LV, Mols F, Gundy CM, Creutzberg CL, Nout RA, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, et al. Normative data for the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC-sexuality items in the general Dutch population. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(5):667–75.

van Leeuwen M, Kieffer JM, Efficace F, Fosså SD, Bolla M, Collette L, et al. International evaluation of the psychometrics of health-related quality of life questionnaires for use among long-term survivors of testicular and prostate cancer. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1):97. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-017-0670-4.

Fayers PM, Hand DJ. Factor analysis, causal indicators and quality of life. Qual Life Res. 1997;6(2):139–50. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1026490117121.

Fayers PM, Hand DJ. Causal variables, indicator variables and measurement scales: an example from quality of life. 2002;165(2):233-53.https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-985x.02020.

Fayers PM, Hand DJ, Bjordal K, Groenvold M. Causal indicators in quality of life research. Qual Life Res. 1997;6(5):393–406. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1018491512095.

Kieffer JM, Verrips E, Hoogstraten J. Model specification in oral health-related quality of life research. Eur J Oral Sci. 2009;117(5):481–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0722.2009.00650.x.

Kilburn LS, Banerji J, Bliss JM. The challenges of long-term follow-up data collection in non-commercial, academically-led breast cancer clinical trials: the UK perspective. Trials. 2014;15:379. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-15-379.

Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, et al. The European organization for research and treatment of cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365–76.

Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, et al. The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11(3):570–9.

Zhao L, Portier K, Stein K, Baker F, Smith T. Exploratory factor analysis of the cancer problems in living scale: a report from the American cancer society’s studies of cancer survivors. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37(4):676–86.

Zebrack BJ, Ganz PA, Bernaards CA, Petersen L, Abraham L. Assessing the impact of cancer: development of a new instrument for long-term survivors. Psychooncology. 2006;15(5):407–21.

Crespi CM, Ganz PA, Petersen L, Castillo A, Caan B. Refinement and psychometric evaluation of the impact of cancer scale. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(21):1530–41. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djn340.

Crespi CM, Ganz PA, Petersen L, Smith SK. A procedure for obtaining impact of cancer version 2 scores using version 1 responses. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(1):103–9.

Wyatt G, Kurtz ME, Friedman LL, Given B, Given CW. Preliminary testing of the long-term quality of life (LTQL) instrument for female cancer survivors. J Nurs Meas. 1996;4(2):153–70.

Gordon NH, Siminoff LA. Measuring quality of life of long-term breast cancer survivors: the long term quality of life-breast cancer (LTQOL-BC) Scale. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2010;28(6):589–609. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347332.2010.516806.

Avis NE, Ip E, Foley KL. Evaluation of the quality of life in adult cancer survivors (QLACS) scale for long-term cancer survivors in a sample of breast cancer survivors. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:92.

Avis NE, Smith KW, McGraw S, Smith RG, Petronis VM, Carver CS. Assessing quality of life in adult cancer survivors (QLACS). Qual Life Res. 2005;14(4):1007–23.

Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Leedham B, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, Belin TR. Quality of life in long-term, disease-free survivors of breast cancer: a follow-up study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(1):39–49.

Alfano CM, McGregor BA, Kuniyuki A, Reeve BB, Bowen DJ, Wilder Smith A, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the brief cancer impact assessment among breast cancer survivors. Oncology. 2006;70(3):190–202. https://doi.org/10.1159/000094320.

Ferrell BR, Dow KH, Grant M. Measurement of the quality of life in cancer survivors. Qual Life Res. 1995;4(6):523–31.

Baker F, Denniston M, Hann D, Gesme D, Reding DJ, Flynn T, et al. Factor structure and concurrent validity of the satisfaction with life domains scale for cancer (SLDS-C). J Psychosoc Oncol. 2007;25(2):1–17.

Bottomley A, Pe M, Sloan J, Basch E, Bonnetain F, Calvert M, et al. Analysing data from patient-reported outcome and quality of life endpoints for cancer clinical trials: a start in setting international standards. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(11):e510–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30510-1.

US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. Silver Spring, MD. 2009.

European Medicines Agency Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use. Appendix 2 to the guideline on the evaluation of anticancer medicinal products in man: the use of patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures in oncology studies EMA/CHMP/292464/2014. London, England. 2016.

Bottomley A, Reijneveld JC, Koller M, Flechtner H, Tomaszewski KA, Greimel E. Current state of quality of life and patient-reported outcomes research. Eur J Cancer. 2019;121:55–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2019.08.016.

Lisy K, Ly L, Kelly H, Clode M, Jefford M. How do we define and measure optimal care for cancer survivors? An online modified reactive Delphi study. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(10):2299. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13102299.

Calvert M, Kyte D, Mercieca-Bebber R, Slade A, Chan AW, King MT, et al. Guidelines for inclusion of patient-reported outcomes in clinical trial protocols: the SPIRIT-PRO extension. JAMA. 2018;319(5):483–94. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.21903.

Cuzick J. Statistical controversies in clinical research: long-term follow-up of clinical trials in cancer. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(12):2363–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdv392.

Ye M, Du K, Zhou J, Zhou Q, Shou M, Hu B, et al. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of cognitive behavior therapy on quality of life and psychological health of breast cancer survivors and patients. Psychooncology. 2018;27(7):1695–703. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4687.

Kim SH, Kim K, Mayer DK. Self-management intervention for adult cancer survivors after treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2017;44(6):719–28. https://doi.org/10.1188/17.Onf.719-728.

Duncan M, Moschopoulou E, Herrington E, Deane J, Roylance R, Jones L, et al. Review of systematic reviews of non-pharmacological interventions to improve quality of life in cancer survivors. BMJ Open. 2017;7(11): e015860. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-015860.

Jefford M, Ward AC, Lisy K, Lacey K, Emery JD, Glaser AW, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in cancer survivors: a population-wide cross-sectional study. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(10):3171–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3725-5.

Van de Poll-Franse LV, Horevoorts N, Eenbergen MV, Denollet J, Roukema JA, Aaronson NK, et al. The patient reported outcomes following initial treatment and long term evaluation of survivorship registry: scope, rationale and design of an infrastructure for the study of physical and psychosocial outcomes in cancer survivorship cohorts. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(14):2188–94.

Halpern MT, Argenbright KE. Evaluation of effectiveness of survivorship programmes: how to measure success? Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(1):e51–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30563-0.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all of the cancer survivors for their willingness to participate in this study. We also thank Johannes Giesinger for his statistical advice and Imogen Ramsey for her advice on the Delphi Study.

EORTC survivorship questionnaire development group (in alphabetical order)

Neil K. Aaronson, Division of Psychosocial Research & Epidemiology, The Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Maria Antonietta Annunziata, Unit of Oncological Psychology, Centro di Riferimento Oncologico di Aviano (CRO) IRCCS, Aviano, Italy

Volker Arndt, Unit of Cancer Survivorship Research, Division of Clinical Epidemiology and Aging Research & Epidemiological Cancer Registry Baden-Württemberg, German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Heidelberg, Germany

Juan Ignacio Arraras, Oncology Departments, Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra, Pamplona, Pamplona, Spain

Didier Autran, Pôle Neurosciences Cliniques, Service de Neuro-Oncologie, Aix-Marseille Université, Marseille, France

Hira Bani Hani, King Hussein Cancer Center, Amman, Jordan

Manas Chakrabarti, Columbia Asia Hospital, Kolkata, India

Olivier Chinot, Pôle Neurosciences Cliniques, Service de Neuro-Oncologie, Aix-Marseille Université, Marseille, France

Juhee Cho, Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Cancer Education Center, Samsung Medical Center, School of Medicine Sungkyunkwan University, Seoul, Korea

Rene Aloisio da Costa Vieira,, Postgraduate Program in Oncology, Barretos Cancer Hospital, Barretos, São Paulo, Brazil

Anne-Sophie Darlington, School of Health Sciences, University of Southampton, UK

Philip R. Debruyne, Kortrijk Cancer Centre, General Hospital Groeninge, Kortrijk, Belgium

Linda Dirven, Department of Neurology, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, the Netherlands

Daniela Doege, Unit of Cancer Survivorship Research, Division of Clinical Epidemiology and Aging Research & Epidemiological Cancer Registry Baden-Württemberg, German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Heidelberg, Germany

Yannick Eller, Centre for Medical Education, University of Dundee (UK)

Martin Eichler, National Center for Tumor Diseases (NCT/UCC), University Hospital Carl Gustav Carus Dresden, Dresden, Germany

Nanna Friðriksdóttir, National University Hospital of Iceland

Ugo De Giorgi, Department of Medical Oncology, IRCCS Istituto Romagnolo per lo Studio dei Tumori (IRST) "Dino Amadori", Meldola 47014, Italy

Ioannis Gioulbasanis, Chemotherapy Department, Larissa General Clinic “E Patsidis”, Athens, Greece

Eva Hammerlid, Department of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Göteborg, Sweden

Mieke van Hemelrijck Translational Oncology & Urology Research (TOUR), School of Cancer and Pharmaceutical Sciences, King’s College London, UK

Silke Hermann, Epidemiological Cancer Registry Baden-Württemberg, German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Heidelberg, Germany

Olga Husson Division of Clinical Studies, Institute of Cancer Research, London, UK

Michael Jefford, Department of Health Services Research, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Melbourne, Australia

Christoffer Johansen, Oncology clinic, Finsen Center, Copenhagen

Colin Johnson, University Surgical Unit, University Hospitals Southampton, Southampton, UK

Jacobien M Kieffer, Division of Psychosocial Research & Epidemiology, The Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Trille Kristina Kjaer, Survivorship and Inequality in Cancer, Danish Cancer Society Research Center, Copenhagen, Denmark

Meropi Kontogianni, Department of Nutrition & Dietetics, School of Health Sciences and Education, Harokopio University, Athens, Greece

Pernilla Lagergren,Department of Molecular medicine and Surgery, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

Marieke van Leeuwen, Division of Psychosocial Research & Epidemiology, The Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, the Netherlands

Emma Lidington, The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK

Karolina Lisy, Department of Health Services Research, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Melbourne, Australia

Ofir Morag, Oncology Institute, Chaim Sheba Medical Center, Tel-Hashomer, Israel

Andy Nordin, East Kent Gynaecological Oncology Centre, Margate, UK

Amal S.H. Al Omari, King Hussein Cancer Center, Amman, Jordan

Andrea Pace, Neuroncology Unit, National Cancer Institute Regina Elena, Rome, Italy

Silvia De Padova, Psycho-Oncology Unit, IRCCS Istituto Romagnolo per lo Studio dei Tumori (IRST) “Dino Amadori” 47014 Meldola, Italy

Duska Petranoviæ, Hematology Department, University Clinical Hospital Center Rijeka, Medical faculty University of Rijeka, Rijeka, Croatia

Monica Pinto, Rehabilitation Medicine Unit, Department of StrategicStrategic Health Services , Istituto Nazionale Tumori – IRCCS—Fondazione G. Pascale , Naples, Italy

Lonneke V. van de Poll-Franse, Division of Psychosocial Research & Epidemiology, The Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, the Netherlands

John Ramage, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Hampshire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Basingstoke, UK

Elke Rammant, Translational Oncology & Urology Research (TOUR), School of Cancer and Pharmaceutical Sciences, King’s College London, UK

Jaap Reijneveld, Department of Neurology and Brain Tumor Center Amsterdam, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Samantha Serpentini, Unit of Psychoncology—Breast Unit, Istituto Oncologico Veneto (IOV)-IRCCS, Padua, Italy

Sam Sodergren, School of Health Sciences, University of Southampton, UK

Vassilios Vassiliou, Department of Radiation Oncology, Bank of Cyprus Oncology Centre, Nicosia, Cyprus

Irma Verdonck-de Leeuw, Department of Otolaryngology / Head & Neck Surgery, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Ingvild Vistad, Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Sorlandet Hospital Kristiansand, Norway

Teresa Young, Lynda Jackson Macmillan Centre, Mount Vernon Cancer Centre, Northwood, UK

Funding

This study was funded by the a grant from the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Group (006/2016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation performed by Marieke van Leeuwen, Neil Aaronson, Lonneke van de Poll-Franse, and Teresa Young. Data analysis was carried out by Marieke van Leeuwen, Neil Aaronson, Jacobien Kieffer, and Lonneke van de Poll-Franse. All authors, except for Neil Aaronson, Jacobien Kieffer, and Lonneke van de Poll-Franse, participated in data collection. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Marieke van Leeuwen, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee (Institutional Review Board of the Netherlands Cancer Institute; M17QOL) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

van Leeuwen, M., Kieffer, J.M., Young, T.E. et al. Phase III study of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life cancer survivorship core questionnaire. J Cancer Surviv 17, 1111–1130 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-021-01160-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-021-01160-1