Abstract

Extant research on salespersons’ regulatory foci has mainly focused on behaviors that are congruent with salespersons’ regulatory orientations (dominant pathway) to the neglect of alternate, yet essential salesperson behaviors that may render less “fit” (supplemental pathway). Moreover, the literature is also silent on managerial actions that can motivate salespeople to perform even when the environment is not conducive to perceived fit. Using a triadic dataset from salespeople, their managers, and archival performance records, the authors find that a competitive psychological climate can strengthen the regulatory fit of promotion focus and adaptive selling, which can be further reinforced (inadvertently disrupted) if managers deploy outcome (behavioral) control. By contrast, prevention focus shows an opposite pattern, in which behavioral control strengthens, whereas outcome control weakens, the perceived fit of prevention focus and service behaviors in a highly competitive climate. Importantly, our findings elucidate the complementary (as opposed to contradictory) nature of the dual process model of dominant and supplemental pathways, by illustrating their positive synergistic effect on salesperson performance. Together, these findings clarify the underlying dual mechanisms of regulatory foci and their respective boundary conditions, thereby shedding light on ambiguities in extant literature and providing actionable managerial guidance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Regulatory focus theory examines the relationship between an individual’s motivational orientation and how they go about accomplishing desired goals (Higgins, 1997). There are two distinct self-regulatory orientations that influence an individual’s approach to her/his goals: promotion focus and prevention focus. A promotion-focused person is mainly concerned with higher levels of gains such as professional advancement and accomplishment. By contrast, a prevention-focused individual emphasizes safety and meeting responsibilities, also known as non-losses, typically by following established rules and guidelines.

In sales research, regulatory focus theory has been applied extensively to explain salespersons’ goal pursuit processes. Empirical evidence suggests that perceived fit with regulatory foci has positive effects on salespeople’s motivation to perform and job-related outcomes (DeCarlo & Lam, 2016; Hartmann et al., 2020; Katsikeas et al., 2018; Mullins et al., 2019). Despite increasing attention on regulatory foci in the sales setting, however, a careful review of empirical research reveals two important research gaps.

First, researchers suggest that perceived fit between regulatory focus and a corresponding goal pursuit behavior can interact with contextual factors that either reinforce or disrupt the perceived fit therein (Gorman et al., 2012; Johnson et al., 2015; Lanaj et al., 2012). The influence of contextual factors on regulatory fit has received extensive empirical support (e.g., Byron et al., 2018; DeCarlo & Lam, 2016; Katsikeas et al., 2018; Mullins et al., 2019). For example, Byron et al. (2018) find that challenge (hindrance) stress enhances the positive effect of promotion (prevention) focus on job performance. In another study, Mullins et al. (2019) report that the salesperson’s perceived empowering of customer behaviors weakens (reinforces) the regulatory fit between promotion (prevention) focus and value-based selling. While insights from these studies are certainly valuable, they tested contextual factors in a piecemeal fashion without considering simultaneous managerial actions (i.e., a concurrent contextual factor) that can (1) motivate salespeople to perform even when the environment is not conducive to perceived fit, (2) further reinforce, or (3) inadvertently disrupt perceived fit in an otherwise fit-facilitating environment. Because all contextual factors will not likely enable regulatory fit, it is particularly important, from a managerial standpoint, to investigate courses of action that can motivate salespeople to perform especially when the environment fails to facilitate regulatory fit. From a theoretical perspective, identification of appropriate intervening managerial actions can also enrich insights offered through regulatory focus theory applied in the sales setting.

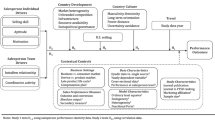

Second, although prior research generally has confirmed positive effects of regulatory foci on performance through behaviors that are congruent with an individual’s regulatory orientation (i.e., dominant pathway), the literature is mostly silent on the role of alternate, yet essential work-related behaviors that may render less fit with a salesperson’s regulatory orientation (i.e., supplemental pathway). Because effective selling calls for a combination of alternate selling strategies and behaviors that may or may not be compatible with a salesperson’s regulatory focus, the following questions arise: What is the role of an essential salesperson behavior that renders less “fit” with her/his regulatory focus? Does it detract from or complement effects of a job-related behavior that is compatible with a salesperson’s regulatory focus? Figure 1 summarizes the two research gaps identified above.

Literature review of individual-level regulatory foci. Note: Additional exemplary variables can be found in Web Appendix A. The upper panel reviews themes in prior research. The lower panel identifies research gaps that will be addressed in this research

Contemporary buyer-seller exchange is relational in nature and requires salespeople to not only meet sales targets but to build high-quality and sustainable customer relationships (Ahearne et al., 2007; Palmatier et al., 2006). Against this backdrop, we identify two alternate salesperson relational behaviors–adaptive selling and service behaviors–that may serve as dominant and supplemental pathways for promotion vs. prevention focus. Adaptive selling is defined as “the altering of sales behaviors during a customer interaction or across customer interactions based on perceived information about the nature of the selling situation” (Weitz et al., 1986, p. 175), whereas service behaviors refer to behaviors that salespeople engage in that are aimed at nurturing customer relationships (Ahearne et al., 2007; Liao & Chuang, 2004). According to self-discrepancy theory (Higgins, 1987, 1989), individuals are motivated to reduce discrepancies between actual self and two types of “self-guides”, namely ideal vs. ought self-guides, as a more desired end state. These self-guides are motivationally distinct in that ideal self-guides approach goals with aspirations for maximal achievements while embracing higher levels of risks, whereas ought self-guides focus on avoidance of errors and negative outcomes by cautiously fulfilling necessary duties and obligations. Noteworthy is that most people are motivated to attain both ideal and ought self-guides to certain degrees, but one type of self-guides typically predominates, thereby making ideal (ought) self-guides the dominant motivational driver for promotion (prevention)-focused individuals (Higgins, 1998). In the context of this study, adaptive selling is a proxy for ideal self-guides because of its strategic inclination to maximize “hits” and minimize “errors of omission” despite higher uncertainties in performance outcomes (Cron et al., 2021; Higgins, 1998; McFarland et al., 2006). By contrast, salesperson service behaviors reflect a type of ought self-guides in that they enable the salesperson to more effectively (from a risk aversion perspective) meet customers’ expressed needs, which helps attain their “non-losses” goals (e.g., lowering customer defection rates) through higher customer satisfaction and trust (Ahearne et al., 2007; Amyx & Bhuian, 2009; Challagalla, Venkatesh, and Kohli 2009). To the extent that adaptive selling and service behaviors are both fundamental building blocks for a variety of relational selling strategies critical to sales successes (Ahearne et al., 2005; Franke & Park, 2006; Liao & Chuang, 2004), we investigate differential mediation effects of these two alternate salesperson behaviors in our research framework.

Using a triadic dataset from 391 salespeople, 50 sales managers, and their firms’ archival performance records, we find empirical evidence in support of our research framework. Specifically, it was found that competitive psychological climate can strengthen the perceived fit of promotion focus and adaptive selling (i.e., dominant pathway), which can be further reinforced if managers deploy outcome control; whereas behavioral control is likely to disrupt the existing fit therein. By contrast, prevention focus shows an opposite pattern. Although a highly competitive climate does not directly facilitate perceived fit of prevention focus and service behaviors (i.e., dominant pathway), managers can still motivate salespeople to perform services through the use of behavioral control, whereas outcome control exacerbates lack of fit in a highly competitive climate. Our findings provide guidance for what managers should do to (1) motivate their salespeople to perform even when the environment is not conducive to perceived fit, (2) strengthen an existing fit, and (3) what they should not do to avoid disrupting what otherwise would be perceived fit. Moreover, our findings highlight the neglected role of the “supplemental pathway” through less “fitting” alternate salesperson behaviors, which can actually produce a positive synergistic effect with the “dominant pathway” on salesperson performance. This study contributes to the literature by elucidating the complementary underlying dual process mechanisms of regulatory foci as well as their respective boundary conditions, thereby shedding light on ambiguities in the extant literature and providing actionable managerial guidance.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. After reviewing the background literature and theoretical foundations, we formulate a conceptual model that addresses the differential effects of regulatory foci under select contextual conditions. We then describe our research methods that include the details about our sample and data collection, measurement of variables, analytical approaches, and results of hypotheses testing. The method section is followed by discussions of theoretical and managerial implications. Finally, we conclude our study with limitations and future research directions.

Background literature, theoretical foundations and conceptual framework

Regulatory focus theory

According to regulatory focus theory, individuals approach their goals through two different self-regulatory orientations: promotion focus and prevention focus (Higgins, 1997, 1998). These two regulatory orientations reflect individuals’ distinct values and beliefs about goal pursuit, which result in differences in attitudes, motivations, emotions, and behaviors when performing tasks. Promotion-focused people are mainly driven by positive results, are motivated by higher levels of gains such as professional growth and accomplishments, and are more willing to take risks as long as they can learn and apply new knowledge and skills (Crowe & Higgins, 1997; Higgins et al., 1997; Idson et al., 2000; Liberman et al., 1999). That is, promotion-focused people are more likely to generate creative ideas and find new solutions because they “actively pursue goals by trying out numerous behaviors to see what works” (Johnson et al., 2015, p.1503). In the sales context, promotion-focused salespeople tend to engage in exploratory learning during customer interactions, which entails opportunity-seeking and experimentation with new selling techniques (DeCarlo & Lam, 2016; Katsikeas et al., 2018). Therefore, promotion-focused people experience reinforced positive feelings when they can score higher levels of accomplishments in a more adaptive and creative fashion, even when so doing carries higher levels of performance risks (Higgins, 1998).

By contrast, prevention-focused people are motivated to avoid negative outcomes. Unlike their promotion-focused counterparts, prevention-focused salespeople tend to place high importance on security and safety, categorize results as “losses” vs. “non-losses,” have a preference for stability, and adhere to tried-and-true ways of doing things by following guidelines and rules (Crowe & Higgins, 1997; Idson et al., 2000; Liberman et al., 1999). In other words, prevention-focused individuals are mainly concerned with avoiding “errors of commission” (Higgins, 1998), with a predominant motivation to avoid making unnecessary mistakes while accomplishing their goals.

Regulatory fit theory

Building on regulatory focus theory, Higgins (2000) advanced regulatory fit theory, which posits that individuals experience greater motivational strength, positive emotion, and intensified commitment to what they are doing if there is perceived fit between their regulatory orientation and the means used for goal pursuit (Avnet & Higgins, 2006; Motyka et al., 2014). When individuals perceive regulatory fit, they experience positive reinforcement of their motives, which contributes to job-related satisfaction, work engagement, and performance (Aaker & Lee, 2006; Freitas & Higgins, 2002; Higgins, 2005).

Prior research has focused on identifying various situational factors that nurture regulatory fit, given an individual’s promotion versus prevention orientation. For example, Byron et al. (2018) report that challenge stress enhances the positive effect of promotion focus, whereas hindrance stress amplifies the positive impact of prevention focus, on job performance. Dimotakis et al. (2012) find that promotion-focused employees in divisional structures, and prevention-focused employees in functional structures, experience stronger regulatory fit, which contributes to more effective team performance. Wallace et al. (2016) find that promotion-focused employees experience reinforced regulatory fit in the presence of high employee involvement climates. While these studies have certainly enriched our understanding of regulatory fit, they have failed to address what managers can do to restore a salesperson’s motivation to perform when the environment is not conducive to perceived regulatory fit. Another equally important issue is the role managers can play in reinforcing perceived fit when a given sales environment is in alignment with a salesperson’s regulatory focus, instead of inadvertently disrupting such fit. Answers to these questions can offer deeper insights into the regulatory fit literature and provide clearer guidelines for managerial practice.

Another notable ambiguity in the literature relates to effects of alternate work behaviors that render less fit with an individual’s regulatory orientation, because empirical research has typically focused on mediators that are congruent with regulatory foci. Since regulatory fit theory does not explicitly specify the role of those secondary mechanisms, the extent to which alternate, yet essential work behaviors that are less compatible with an individual’s regulatory orientation may detract from or complement performance outcomes remains elusive. Toward that end, self-discrepancy theory (Higgins, 1987, 1989) provides useful insights.

Self-discrepancy theory

Self-discrepancy theory identifies three basic domains of the self: the actual self, the ideal self, and the ought self (Higgins, 1987). The actual self refers to the representation of the attributes one believes s/he actually possesses; the ideal self is the representation of the attributes that an individual ideally would like to possess; the ought self reflects someone’s beliefs about the duties and obligations that they ought to fulfill. While people can be motivated to simultaneously reduce actual-ideal and actual-ought self-discrepancies, one type of self-guides typically predominates, which is especially salient to one’s particular regulatory orientation (Higgins, 1998). That is, the significance of either type of self-discrepancy depends on how important they are to individuals’ regulatory foci, and, it is the predominant self-discrepancy that has the stronger influence on goal pursuit behaviors (Higgins, 1987, 1998). Given that promotion focus is concerned with maximal accomplishments and aspirations, it predominantly motivates individuals through ideal self-guides characterized by “gains/no gains” as a frame of reference. In contrast, prevention focus elevates ought self-guides as a more desirable end state because this type of self-guides emphasizes responsibilities, obligations, and absence of negative outcomes (Brendl et al., 1995). In short, self-discrepancy theory suggests that regulatory foci have a dominant as well as a supplemental pathway through ideal self- and ought self-guides, which is a function of promotion vs. prevention focus. In the sales setting, however, it is still not clear what salesperson behaviors may serve as ideal vs. ought self-guides, nor do we know whether their effects are simply additive or can be complementary to each other.

Conceptual model and hypotheses development

The dual process mechanisms of regulatory foci

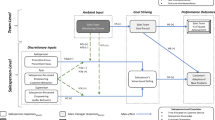

Integrating insights derived from regulatory focus, regulatory fit, and self-discrepancy theories, we investigate differential effects of regulatory foci as depicted in Fig. 2. To the extent that relational selling calls for varying degrees of adaptive selling and service behaviors (Ahearne et al., 2007; McFarland et al., 2006), we position adaptive selling and service behaviors as either the dominant or the supplemental pathway depending on the specific orientation of a salesperson’s regulatory foci.

We argue that promotion-focused salespeople are especially motivated to practice adaptive selling for the following reasons. First, promotion focus is characterized by a strong learning orientation to obtain new knowledge and skills necessary to develop abilities and competence (Gorman et al., 2012; Higgins, 1998), which motivates salespeople to engage in exploratory learning by searching for and experimenting with new selling techniques, an essential prerequisite for salespersons’ adaptive selling (Katsikeas et al., 2018). Second, adaptive selling likely serves as ideal self-guides for promotion-focused salespeople because it is a defining attribute of effective selling (Spiro & Weitz, 1990), which affords salespeople extensive opportunities for knowledge acquisition, professional growth, and goal accomplishments. Because adaptive selling entails experimenting with a wide variety of selling approaches in order to effectively vary sales styles from situation to situation, adaptive selling is expected to be strongly aligned with promotion focus. Although adaptive selling is demanding on the part of salespeople and is inherently characterized by higher levels of uncertainties and risks in terms of sales performance (Cron et al., 2021; McFarland et al., 2006), promotion-focused salespeople tend to be risk-biased and are more likely to refrain from committing errors of omission due to the “gains/no gains” as opposed to the “losses/non-losses” mindset (Higgins, 1998). Therefore, for promotion-focused salespeople, adaptive selling enables them to meet and uphold their ideal self-perception.

Conversely, promotion-focused salespeople may find it less appealing to pursue superior sales performance through service behaviors. Because service behaviors are preventative in nature and intended to avert risks related to customer issues (Challagalla, Venkatesh, and Kohli 2009), they represent responsibilities and obligations that salespeople ought to perform for creating customer satisfaction and preventing customer attrition (Rust et al., 1995). Therefore, given their preventative nature and a conservative bias (Challagalla, Venkatesh, and Kohli 2009), service behaviors would qualify as ought self-guides. Although self-discrepancy theory explicitly suggests that an individual can be motivated by both ideal- and ought-self guides, the theory posits that one particular type of self-guides is usually much more salient as a function of the individual’s regulatory orientation being promotion- or prevention-focused (Higgins, 1998). As such, while it is conceivable that a promotion-focused salesperson can also strive to meet the minimum level of ought self-guides (i.e., service behaviors), the ideal self-guides (i.e., adaptive selling) should bear much stronger motivational significance given its stronger alignment with the salesperson’s regulatory orientation (Higgins, 1987, 1998). As such, we expect the effects of promotion focus on salesperson performance to demonstrate a dominant pathway via adaptive selling with service behaviors in a supplemental role.

Compared with their promotion-focused counterparts, prevention-focused salespeople have stronger motivations to meet their ought self-guides. Because prevention-focused salespeople prioritize the absence of negative outcomes (e.g., non-losses) over the presence of positive outcomes (e.g., maximal gains), they have a strategic orientation to avoid unnecessary risks by mainly meeting responsibilities that are either clearly necessary or more safely attainable (Higgins, 1998). In particular, service behaviors provide a proactive means of detecting and preventing imminent customer-related problems (Challagalla, Venkatesh, and Kohli 2009), thereby effectively facilitating prevention-focused salespeople to meet variance-reduction goals during customer engagement.Footnote 1 Given the pivotal role of service provision in the domain of CRM technology (Agnihotri et al., 2017) and post-sales relationship nurturance (Ahearne et al., 2007), proactive service activities give prevention-focused salespeople a sense of security and stability by effectively mitigating occurrences of negative outcomes (e.g., customer defection). Moreover, prevention-focused salespeople are more prone to engaging in impression management than their promotion-focused counterparts during customer interactions (Lalwani, Shrum, and Chiu 2009), and are more likely to display socially desirable behaviors (e.g., exchanging light banter) toward customers for social approval (King & Booze, 1986). Therefore, prevention focus is expected to affect salesperson performance mainly through service behaviors as the dominant pathway. By contrast, adaptive selling entails higher degrees of uncertainties and risks because it prioritizes constant change over stability, which can easily subject the salesperson to errors of commission such as inaccurate intuitions (Cron et al., 2021) or inappropriate influence tactics (McFarland et al., 2006). As such, adaptive selling is not likely a very compatible approach to goal accomplishment for prevention-focused salespeople. Despite that, all sales jobs will nonetheless require some degree of adaptiveness to be successful (Franke & Park, 2006). To fulfill their job responsibilities and obligations, therefore, prevention-focused salespeople still need to maintain a certain degree of adaptiveness, thereby safeguarding their job security (Higgins, 1998). However, because of concerns with payoffs of adaptive selling given the uncertainties and risks therein (Cron et al., 2021; Spiro & Weitz, 1990), adaptive selling will be practiced to a much lesser degree by prevention-focused salespeople, thereby serving as a supplemental pathway. We expect that:

-

H1 Regulatory foci have dual mediation pathways, such that promotion (prevention) focus affects sales performance via the dominant pathway of adaptive selling (service behaviors) and the supplemental pathway of service behaviors (adaptive selling).

Moderation effects of competitive psychological climate

Competitive psychological climate is a hallmark of the sales occupation, which refers to “the degree to which employees perceive organizational rewards to be contingent on comparisons of their performance against that of their peers” (Brown et al., 1998; p. 89). We argue that the meaning of competitive psychological climate is construed in an opposite fashion by promotion-focused vs. prevention-focused salespeople.Footnote 2 According to the job demands–resources model, job demands can be divided into challenge demands and hindrance demands that have opposite effects on employee job engagement and commitment to goals (Demerouti & Bakker, 2011; Friedman & Förster, 2001). Challenge demands are perceived by salespeople as opportunities for promoting professional competence and personal growth, thereby triggering positive emotion and intensified job engagement; by contrast, hindrance demands are perceived as threats that reduce salespersons’ abilities to accomplish their desired goals, which can subsequently induce job stress and disengagement. For promotion-focused salespeople who are mainly motivated by positive outcomes, competitive psychological climate is more likely perceived as a challenge demand, which strengthens their desire for upholding the ideal self-guides by outperforming their peers (i.e., gains). Therefore, a competitive climate should strengthen the regulatory fit of promotion focus and adaptive selling.

By contrast, prevention-focused salespeople concerned with avoiding negative outcomes may feel increased pressure and anxiety when they are postured in comparison to their peers (Higgins, 1997, 1998). As such, a highly competitive climate may be perceived as a hindrance demand because it would make poor performance much more salient, thereby threatening “non-losses” goal attainment as well as job security. Consequently, a competitive climate may amplify perceived size of losses, which can demotivate prevention-focused salespeople from performing service behaviors due to increased negative feelings, fears and disengagement.

-

H2a Competitive psychological climate strengthens the positive relationship between promotion focus and adaptive selling.

-

H2b Competitive psychological climate weakens the positive relationship between prevention focus and service behaviors.

Moderation effects of sales controls

As previously discussed, competitive psychological climate can either disrupt or reinforce perceived fit depending on a salesperson’s regulatory orientation. A logical follow-up question is “What should managers do to maintain the salesperson’s motivation to perform in the event that the environment is not conducive to perceived fit?” Another equally important question is “When the environment does facilitate perceived fit, what should managers do to reinforce an existing fit as opposed to inadvertently disrupting it?”

One of the most common and important managerial tools used for directing salespeople to achieve desired organizational objectives is the sales control system, which refers to “an organization’s set of procedures for monitoring, directing, evaluating, and compensating its employees” (Anderson & Oliver, 1987, p. 76). The literature suggests that sales controls play an important role in affecting both salespersons’ selling and service behaviors (Anderson & Oliver, 1987; Hartline & Ferrell, 1996; Oliver & Anderson, 1994). Sales control systems are broadly characterized as either behavioral controlFootnote 3 or outcome control (Anderson & Oliver, 1987; Ahearne et al., 2013). A main advantage of behavioral control is that it affords sales managers the ability to actively monitor, direct, support, and reward salespeople based on their performance of required activities during customer interactions. For example, under behavioral control, sales managers can provide feedback and support based on their evaluations of salespeople’s performance in terms of effort, ability, and strategies. By contrast, in outcome control, sales managers provide little behavioral guidance in the selling process and instead rely on sales outcomes (e.g., quota attainment) to evaluate and reward salespeople. Moreover, whereas behavioral goals can be subjective (e.g., salesperson’s presentation skills, customer-oriented selling) or objective in nature (e.g., customer satisfaction index, number of sales calls made),Footnote 4 outcome goals are primarily measured by some indicator of sales performance (e.g., sales volume, quota achievement). Noteworthy is that under behavioral control the perceived risk for salespeople is typically lower, because they are evaluated and rewarded on the basis of how they perform required activities by following managerial instructions. Conversely, although outcome control grants autonomy and freedom in the selling process, salespeople face higher levels of performance risks because their sales output as well as associated rewards may be affected by factors beyond their control (Oliver & Anderson, 1994).

We are especially interested in the moderating roles of outcome control vs. behavioral control when there is a high level of competitive psychological climate. We suggest that a control system can redress a lack of fit, or reinforce a perceived fit, to the extent that it facilitates salespersons’ ability to cope with environmental demands (e.g., increasing competition). If the control system impedes salespeople’s perceived ability to cope with increasing job demands, such managerial practices could undermine an otherwise existing regulatory fit or exacerbate a perceived lack of fit. Specifically, we anticipate that outcome control will reinforce promotion-focused salespersons’ perceived regulatory fit with adaptive selling under a highly competitive psychological climate for the following reasons. First, the use of outcome control is logically compatible with a highly competitive climate that motivates promotion-focused salespeople to seek maximum accomplishments/financial gains by demonstrating superior sales performance relative to peers (Cravens et al., 1993), which serves to meet their ideal self-guides as a desired end state (Higgins, 1998). Second, outcome control affords promotion-focused salespeople a great deal of flexibility to acquire and apply new knowledge and skills necessary for adaptive selling across customer interactions (Komissarouk & Nadler, 2014), thereby enabling them to provide appropriate solutions across customers. Third, outcome control satisfies promotion-focused salespersons’ innate needs for autonomy, which enhances their well-being and nurtures their motivation to perform (Hui et al., 2013). By contrast, prevention-focused salespeople likely feel threatened by a greater level of competitive climate and will be more in need of sales managers’ support and reassurance that their status quo will not be jeopardized in competition with their peers. Because outcome control affords little guidance in either improving salesperson skills or providing behavioral direction during the selling process (Oliver & Anderson, 1994), it can make a competitive climate seem even more threatening to prevention-focused salespeople. As such, for prevention-focused salespeople, outcome control can exacerbate their perceived risks of failing to meet expectations in a highly competitive climate, thereby weakening their motivation to engage in service behaviors.

-

H3a There is a three-way interactive effect of outcome control, competitive psychological climate, and promotion focus, such that competitive psychological climate enhances the effect of promotion focus on adaptive selling only when outcome control is high.

-

H3b There is a three-way interactive effect of outcome control, competitive psychological climate, and prevention focus, such that competitive psychological climate weakens the positive effect of prevention focus on service behaviors only when outcome control is high.

We expect an opposite pattern of moderating effects for behavioral control. When intra-unit competition is fierce, prevention-focused salespersons’ need for security through managerial guidance will be stronger. Therefore, behavioral control is especially useful for prevention-focused salespeople who are anxious and are in greater need of managerial interventions to reduce uncertainties and risks. For prevention-focused salespeople, behavioral control can somewhat restore their confidence in coping with threats induced by a heightened competitive climate, thereby mitigating a perceived lack of fit brought forth by the competitive environment. In stark contrast, behavioral control may be construed as too intrusive by promotion-focused salespeople as it can significantly restrict their autonomy and freedom in taking discretionary courses of action to beat fierce competition for maximal gains. As a result, behavioral control may be perceived as counterproductive by promotion-focused salespeople, especially in a competitive environment, which would undermine their motivation and ability to practice adaptive selling.

-

H4a There is a three-way interactive effect of behavioral control, competitive psychological climate, and promotion focus, such that competitive psychological climate weakens the effect of promotion focus on adaptive selling only when behavioral control is high.

-

H4b There is a three-way interactive effect of behavioral control, competitive psychological climate, and prevention focus, such that competitive psychological climate enhances the positive effect of prevention focus on service behaviors only when behavioral control is high.

Synergistic effects of adaptive selling and service behaviors

Adaptive selling and service behaviors are both important predictors of sales outcomes (Ahearne et al., 2007; Franke & Park, 2006). Adaptive selling has a positive effect on sales performance because it enables salespeople to make real-time adjustments in their sales approaches to match customers’ unique needs and preferences (Sujan et al., 1988). Research has also confirmed the positive influence of service behaviors on performance, due to enhanced service quality and stronger customer loyalty (Amyx & Bhuian, 2009; Liao & Chuang, 2004, 2007). Because positive effects on salesperson performance of both adaptive selling and service behaviors have been documented in the extant literature, we do not formally hypothesize these relationships. Instead, of particular interest is the potential combined synergistic effect of both behaviors on salesperson performance.

In the proposed dual mediation framework adaptive selling is the dominant (supplemental) pathway for promotion (prevention) focused-salespeople, whereas service behaviors serve as the dominant (supplemental) pathway for prevention (promotion) focused-salespeople. If effects of the dominant and supplemental pathways are merely additive, marginalizing the supplemental pathway may be less problematic. However, if the supplemental pathway can actually amplify positive effects of the dominant pathway, it cannot be ignored and should be investigated alongside the dominant pathway in an integrative fashion.

Adaptive selling and service behaviors are anticipated to produce a positive synergistic effect on sales performance for the following reasons. First, customers who receive excellent service are more willing to share relevant information or cues with the salesperson, which decreases the costs of information search and helps the salesperson better understand customers’ needs, thereby improving the effectiveness of adaptive selling (Weitz et al., 1986). Second, service behaviors can induce customers’ favorable perceptions of the salesperson’s competence and credibility, which enhances customer trust and the perceived value of the salesperson’s customized solutions (Agnihotri et al., 2012; Ahearne et al., 2007; Rapp et al., 2017). Third, although adaptive selling is instrumental in new customer acquisition, in contemporary B2B markets it is easier and less costly for customers to switch between competitors due to improved access to information (Jahromi et al., 2014). Therefore, adaptive selling alone may not be sufficient to prevent customer defection if care is not given to ongoing customer relationships after the point of the initial sale. Salespeople who also actively engage in service behaviors are better able to retain existing customers by preventing customer problems and nurturing higher levels of customer satisfaction (Ahearne et al., 2007; Challagalla, Venkatesh, and Kohli 2009), thereby protecting performance outcomes accomplished by adaptive selling. Therefore, it is expected that a positive interactive effect of adaptive selling and service behaviors will be evident based upon the rationale that salespeople who excel in both adaptive selling and service provision are more likely to achieve superior overall performance.

-

H5 Adaptive selling and service behaviors have a positive interactive effect on sales performance.

Research method

Sample and data collection

The manufacturing sector (SIC codes 35) was selected for the empirical testing of our hypotheses because previous studies indicate that sales control systems vary widely in this context (e.g., Challagalla & Shervani, 1996; Miao & Evans, 2013). Following translation–back translation procedures, two independent translators converted an English version of the questionnaire into a Chinese-language version. The translated questionnaire was then presented to salespeople who had more than three years’ experience. Several items were revised according to the salespersons’ feedback, and it was this finalized questionnaire that was used for data collection.

Eighty firms producing pumps for business customers were randomly selected from the Enterprises Yellow Pages in Jiangsu Province in China. To improve the response rate, confidentiality of respondents’ personal information was assured and each of the participating firms was offered the opportunity to access our research findings. Finally, 53 firmsFootnote 5 agreed to participate in this research. In the subsequent data collection process, two research assistants first gave a brief explanation of the data collection procedure to sales managers before asking them to distribute the questionnaires to their subordinate salespeople. A week later, the research assistants collected the questionnaires from the sales managers and their salespeople separately. One month later, each salesperson’s objective annual performance data was provided by their manager. In total, 402 salesperson and 50 sales manager questionnaires were received. The response rate for salespeople was 67%, and the final response rate for sales managers was 94.3%. Eleven questionnaires were excluded from salespeople who either reported inadequate knowledge to answer the survey questions or provided answers with excessive missing data. The average age of salespeople was 35.8 years with a mean sales experience of 8.5 years.

To check for nonresponse bias, the procedures suggested by Armstrong and Overton (1977) were conducted. First, respondents were divided into early and late respondents based on when they returned the questionnaires. According to Armstrong and Overton (1977), late respondents are more similar to non-respondents. No significant differences between early and late respondents were found in the values of key variables, indicating that nonresponse bias was not likely an issue. In addition, the average employee size of participating firms was compared with that of nonparticipating firms. No significant differences were found between these two groups, again suggesting that nonresponse bias was not likely a threat in this study.

Measurement

Seven-point Likert scales were used for measurement of constructs. In the salesperson questionnaire, four items each were adopted from Neubert et al. (2008) to measure promotion focus and prevention focus, respectively. Items for promotion focus assess salespersons’ self-regulatory orientation for personal gain and aspirations, whereas items for prevention focus measure salespeople’s concern about losses and need for security. These items were asked in relation to salesperson work contexts which were specific to the focus of this research (see Table 1.) Four items from Fang et al. (2004) were used to measure adaptive selling, which capture adjustment of salesperson behaviors to differences in customer characteristics and preferences. Three items adopted from Brown et al. (1998) were used to capture the degree to which salespeople perceived the climate to be competitive. Three items were adopted to measure service behaviors from Liao and Chuang (2004). In the sales manager’s questionnaire, behavioral control and outcome control (4 items each) were measured using items from Miao and Evans (2013).

To measure salesperson performance, archival data were collected for two consecutive years and the sales growth rate was calculated (measured by the ratio of increased sales in the second year over the annual sales in the first year). Wieseke et al. (2012) explain two benefits of using this performance measure: first, potential confounding factors, such as seasonality and differences in sales territories, can be accounted for. For example, the firms in this study that sell heat pumps have varying sales in different seasons. In addition, some salespeople may face fiercer competition in their sales districts, or manage a greater number of, or larger sales territories, than do other less experienced salespeople. Given such differences, sales growth rate is a more effective measure for salespeople’s performance than other metrics. Second, growth rate has been used commonly as a dependent variable in previous sales studies (e.g., Fu et al., 2010; Gonzalez et al., 2014; Hughes & Ahearne, 2010) and is considered a valid performance measure (Bolander et al., 2021). Finally, six control variables were included: salespersons’ tenure, gender, educational level, salespersons’ job satisfaction and salespersons’ chronic regulatory foci (pervasive traits not specific to the work context)Footnote 6 given their potential impact on selling behaviors and performance (Churchill Jr et al., 1985; DeCarlo & Lam, 2016; Hackman & Oldham, 1975). Three items and two items adapted from Higgins et al. (2001) were used to measure chronic promotion focus and prevention focus, respectively.

Next, the validity and reliability of the constructs were examined. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) showed that the measurement model fit was acceptable: 2/df = 1218.79/398; RMSEA = 0.07; CFI = 0.90. In addition, results also indicated that the composite reliability of all constructs exceeded the cutoff value of 0.7 (see Table 1), and all average variance extracted values (AVE) exceeded the 0.5 benchmark, demonstrating satisfactory reliability and convergent validity of our measures (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). To assess discriminant validity, chi-square tests were conducted for all possible pairs of constructs and then constrained into single-factor models. The results of chi-square tests between these two groups of models indicated that constrained one-factor models were inferior in fit to their two-factor counterparts. Moreover, the AVE for each construct was found to be greater than its squared correlations with all other constructs (see Table 2).

To alleviate concerns about common method variance (CMV), multi-source data were collected from salespeople, their managers, and archival performance data (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Moreover, the Comprehensive CFA Marker Technique was used as recommended by Williams et al. (2010). The marker variable was the firm’s expected contributions from employees (Cronbach’s α = 0.76, details can be found in Web Appendix B). Results suggest that CMV is not likely a serious threat in this study. Harmon’s one-factor test was also conducted and the single common factor only explained 29.7% of total variance. Finally, presence of significant interactive terms further alleviated CMV-related issues because interactions are typically not artifacts of CMV (Siemsen et al., 2010).

Analytical approach

Data were analyzed with conditional mixed-process models (CMP) for hypothesis testing (e.g., Antia et al., 2017). Since salespeople were nested in their respective firms, multilevel analysis was used within CMP for statistical estimates. Between-firm variance was checked by examining the intraclass correlation (ICC). Adaptive selling, service behaviors, and sales performance were used as dependent variables in three separate intercept-only models, and the findings indicated that the lowest ICC (1) for these three intercept-only models were 0.38, 0.49 and 0.09 respectively, which were all higher than the required threshold value of 0.05 (e.g., Bliese, 2000). Therefore, multilevel analysis was appropriate. We also examined ICC (1), ICC (2), and the mean Rwg for competitive psychological climate across firms. Results of these indices (ICC (1) = 0.46, ICC (2) = 0.88 and mean Rwg = 0.85) suggested that competitive psychological climate be aggregated to a Level 2 variable (Klein & Kozlowski, 2000). Finally, all predictors at Level 1 were group mean-centered, moderators were grand-mean centered at Level 2, while group means of Level 1 variables were specified as controls (Hofmann, 1997; Hofmann & Gavin, 1998).

In CMP estimations, the recursive system of a series of equations using adaptive selling, service behaviors and sales performance as outcome variables were specified. The equation for adaptive selling is as follows:

-

Level 1

-

Level 2

where salesperson i = 1 to 391, firm j = 1 to 50; the subscript i refers to the individual salesperson and subscript j refers to the salesperson’s firm.

The equation for service behaviors is as follows:

-

Level 1

-

Level 2

where salesperson i = 1 to 391, firm j = 1 to 50; the subscript i refers to the individual salesperson and subscript j refers to the salesperson’s firm.

The equation for an individual salesperson’s sales performance is as follows:

-

Level 1

-

Level 2

where salesperson i = 1 to 391, firm j = 1 to 50; the subscript i refers to the individual salesperson and subscript j refers to the salesperson’s firm.

Results of hypotheses testing

Table 3 shows the results from CMP. Promotion focus was found to positively relate to adaptive selling (β = 0.35, p < 0.001) and service behaviors (β = 0.12, p < 0.01). Prevention focus is positively related to adaptive selling (β = 0.26, p < 0.001) and service behaviors (β = 0.40, p < 0.001). In subsequent chi-square tests, promotion focus was found to have a stronger impact on adaptive selling than on service behaviors (χ2(1) = 16.09, p < 0.001), whereas prevention focus has a stronger impact on service behaviors than on adaptive selling (χ2(1) = 3.92, p < 0.05). Therefore, these results confirm the proposed dominant vs. supplemental pathways in direct support of H1.

Regarding the moderation effects of competitive psychological climate, as levels of perceived competitive psychological climate increase, the positive relationship between a salesperson’s promotion focus and adaptive selling becomes stronger (β = 0.10, p < 0.05), in support of H2a. Figure 3 illustrates this moderation effect. However, as the level of perceived competitive psychological climate increases, the relationship between prevention focus and service behaviors is not affected (β = 0.11, p > 0.05). Therefore, H2b is not supported.

For the hypothesized three-way interactions involving outcome control, a positive significant three-way effect was found among outcome control, promotion focus, and competitive psychological climate on adaptive selling (β = 0.39, p < 0.001). Therefore, H3a is supported. The plot in Fig. 4A shows that under low levels of outcome control, high levels of competitive psychological climate do not significantly induce promotion-focused salespeople’s adaptive selling. In contrast, Fig. 4B shows that competitive psychological climate strongly motivates salespeople’s adaptive selling when outcome control is high. In addition, a negative significant three-way interactive effect was found among outcome control, prevention focus, and competitive psychological climate on service behaviors (β = −0.56, p < 0.001), in support of H3b. High competitive climate more strongly motivates prevention-focused salespeople’s service behaviors under low levels of outcome control (Fig. 5A) than high levels of outcome control (Fig. 5B). Regarding behavioral control, the three-way negative interactive effect of behavioral control, promotion focus, and competitive psychological climate on adaptive selling is significant (β = −0.23, p < 0.01), in support of H4a. High levels of competitive psychological climate more strongly motivate promotion-focused salespeople’s adaptive selling when behavioral control is low (Fig. 6A) than when behavioral control is high (Fig. 6B). The three-way positive interactive effect of behavioral control, prevention focus, and competitive psychological climate on service behaviors is found to be significant (β = 0.40, p < 0.01), which supports H4b. When competitive psychological climate is high, prevention-focused salespeople are more strongly motivated to engage in service behaviors when behavioral control is high (Fig. 7B) than when it is low (Fig. 7A).

Adaptive selling and service behaviors have a positive synergistic effect on sales performance, as measured by year-over-year sales growth rate (β = 0.04, p < 0.01). The plot in Fig. 8 shows that the impact of adaptive selling on sales performance becomes more positive in the presence of high service behaviors, suggesting the positive synergy between the dominant and supplemental pathways in our research framework. Therefore, H5 is supported.

Finally, the variance inflation factors (VIFs) for the individual-level and disaggregated firm-level predictors were calculated to check for potential multicollinearity. The maximum VIF was found to be 6.02, which is below the threshold value of 10 (Mason & Perreault Jr, 1991), suggesting that multicollinearity was not a serious threat to the validity of our results.

Endogeneity

To rule out the potential endogeneity bias, Lewbel’s (2012) method was used to create instrument variables. According to Lewbel (2012), instruments can be generated by an empirical model if no available instruments are found in the raw data. In this method, identification can be achieved with regressors that are uncorrelated with the product of heteroskedastic errors. The results from the Durbin–Wu–Hausman test (e.g., F (1,373) = 0.37, p > 0.1, n.s.) indicate that endogeneity is not likely an issue in our model. More details can be found in Web Appendix C.

Discussion

Regulatory foci elucidate salespeople’s distinct underlying motivational processes, which have gained traction in recent sales research (DeCarlo & Lam, 2016; Katsikeas et al., 2018; Mullins et al., 2019). Despite increasing knowledge accumulated from extensive empirical studies, however, some notable limitations remain. First, to the extent that the selling environment is not always conducive to perceived regulatory fit, there is a dearth of attention in the literature as to what managers can do to redress a lack of fit. Equally important, when the environment does facilitate regulatory fit, what should managers do to reinforce an existing fit and not inadvertently disrupt it. Second, extant literature has mainly focused on effects of regulatory foci via mediation mechanisms that are compatible with the salesperson’s regulatory orientation (dominant pathway) to the neglect of the role of alternate, yet essential salesperson behaviors that may render less fit with a salesperson’s regulatory focus (supplemental pathway). It is not clear whether the marginalization of the supplemental pathway is warranted, because the extent to which the supplemental pathway can complement or detract from effects of the dominant pathway has remained largely unexplored. Moreover, the sales literature has yet to identify what salesperson behaviors constitute ideal vs. ought self-guides, as posited in self-discrepancy theory, that may serve as the dominant vs. supplemental pathways of regulatory foci. Identification of these alternate behaviors can enrich regulatory focus theory as applied in the sales setting and inform managerial practice. This study addresses these research gaps, thereby providing important insights into theory and practice about managing salespeople given their regulatory orientations.

Theoretical implications

Through the lens of regulatory focus and regulatory fit theories, the sales literature has established the critical moderation role of contextual factors, which can alter salespersons’ motivation to perform by either nurturing or undermining perceived fit. However, given the detrimental consequences of regulatory misfit, it is surprising that the literature stops short of uncovering possible remedies to restore salespeople’s motivation and confidence to perform when the selling environment is not conducive to maintaining a given type of regulatory fit (e.g., Katsikeas et al., 2018; Wallace, Little, and Shull 2008). Similarly, when the environment does facilitate regulatory fit, the literature seems to have taken it as a given without investigating what managerial actions can further reinforce an existing fit or those which may inadvertently disrupt it (e.g., Byron et al., 2018; DeCarlo & Lam, 2016). Findings of this study suggest that the influences of the selling environment on perceived regulatory fit are not necessarily static, but rather can be proactively modified and strengthened by managerial actions.

A key point of this study’s departure from prior literature is its assertion that regulatory fit should not be taken for granted even in fit-enabling environments. Indeed, we show that inappropriate deployment of sales controls can unintentionally disrupt perceived fit in a highly competitive sales climate. While intense competition with peers (i.e., competitive psychological climate) can reinforce promotion-focused salespeople’s motivation to demonstrate their competence and selling prowess through adaptive selling strategies that best resonate with market conditions, managers should cautiously deploy sales controls in this otherwise fit-inducing environment. Behavioral control should generally be avoided with promotion-focused salespeople, because it can restrict their options in choosing the most effective course of action when dealing with intense peer competition, thereby disrupting promotion-focused salespersons’ inclination toward adapting their selling strategies (i.e., regulatory fit). Indeed, our results indicate that promotion-focused salespeople are especially motivated to practice adaptive selling in a highly competitive environment only when behavioral control is deemphasized; when behavioral control is high, a competitive psychological climate does not seem to strengthen their motivation to practice adaptive selling. By contrast, outcome control can further nurture promotion-focused salespeople’s motivation to perform, especially in competitive sales settings, by granting a great deal of autonomy and flexibility conducive to adaptive selling. In fact, when managers employ a very low level of outcome control, promotion-focused salespeople in a highly competitive climate appear to practice even less adaptive selling than their counterparts in a non-competitive environment. A plausible explanation is that the lack of an objective performance-based (e.g., sales volume) reward scheme fails to motivate promotion-focused salespeople to strive for maximal gains characteristic of ideal self-guides (Higgins, 1998).

Although the two-way interactive effect on service behaviors of competitive psychological climate and prevention focus was not found to be significant, a positive result of the three-way interaction when sales controls are included suggests that the two-way interaction should not be interpreted in isolation (Aaker & Lee, 2006; Lam et al., 2019). That is, sales controls are capable of altering the perceived nature and salience of competitive psychological climate by prevention-focused salespeople. To the extent that prevention-focused salespeople primarily rely on proactive service provision to reduce the likelihood of unfavorable customer outcomes (Challagalla, Venkatesh, and Kohli 2009), intense competition among peers necessarily introduces perceived uncertainty to the efficacy of this service-based strategy. When a high level of behavioral control is provided, competitive psychological climate may not appear that intimidating because behavioral control provides much-needed managerial guidance and support during the customer service process, which can address prevention-focused salespeople’s need for security and boost their confidence in maintaining satisfactory performance despite intense competition, thereby motivating them to remain focused on service provision. Indeed, our results suggest that a low level of behavioral control will discourage prevention-focused salespeople from performing service behaviors in a highly competitive environment. By contrast, outcome control can turn intense competition among peers into an even more serious threat for prevention-focused salespeople. This perceived threat is the result of individuals making direct comparisons with peers without the benefit of additional managerial support and guidance in the process, thereby weakening confidence in their ability to prevent losses (to peers) and leading to lower motivation to perform service behaviors. Interestingly, when outcome control is minimal, a highly competitive psychological climate can actually prompt prevention-focused salespeople to embrace service behaviors as a viable coping strategy. As such, sales controls, when employed appropriately with promotion- vs. prevention-focused salespeople, may not only reinforce an existing fit but even reverse a lack of fit in a highly competitive sales environment.

While regulatory fit theory posits that regulatory foci have positive consequences when the means used to approach the desired goal is compatible with an individual’s regulatory orientation, extant literature seems to have generally assumed that goal-pursuit behaviors characterized by lack of fit are mutually exclusive with those rendering perfect fit (e.g., Chamberlin et al., 2017), which are often counterproductive (e.g., van Beek et al., 2014). Consequently, empirical research has mostly focused on work behaviors that are well-aligned with a salesperson’s regulatory orientation to the neglect of alternate, yet essential work behaviors characterized by less “fit”. We argue that this “exclusivity” approach to regulatory foci is unnecessarily narrow and restrictive. Drawing on self-discrepancy theory, this study brings clarity to regulatory fit theory by demonstrating the value of the supplemental pathway through less-than-fitting, yet essential, salesperson behaviors which have been mostly marginalized in extant literature. Our results indicate that the role of the supplemental pathway should not be neglected because it can amplify the positive effects of the dominant pathway on salesperson performance. In particular, we identify two essential, yet qualitatively distinct, salesperson behaviors–adaptive selling and service behaviors–as ideal and ought self-guides, respectively, thereby providing new insights into the complementary nature of the dual mediation mechanisms of regulatory foci. Consistent with regulatory fit theory, we first illustrate that there is a distinct “dominant” pathway through which salespeople approach their goals as a function of their regulatory orientations. Specifically, promotion focus has a positive effect on salesperson performance mainly through adaptive selling (i.e., ideal self-guides), whereas the positive effect of prevention focus on performance is primarily mediated by service behaviors (i.e., ought self-guides). However, a point of departure from extant literature lies in our finding that the alternate work behavior that is not in perfect alignment with the salesperson’s regulatory focus can render a contributing, as opposed to a detracting, synergistic effect on sales performance. While recent studies on sales-service ambidexterity point to the challenge in delivering synergy of these seemingly opposite orientations (e.g., sales vs. service orientation, Gabler et al., 2017), we find growing supportive evidence for the importance of promotion/prevention focus in motivating complementary salesperson behaviors (e.g., DeCarlo & Lam, 2016).Footnote 7 Therefore, both the dominant and the supplemental pathways, albeit opposite for promotion- vs. prevention-focused salespeople, must be taken into account in a holistic fashion.

For promotion-focused salespeople, adaptive selling (i.e., the dominant pathway) and service behaviors (i.e., the supplemental pathway) differ only in degree of salience and are not mutually exclusive. Therefore, promotion-focused salespeople will still perform service behaviors, albeit to a lesser degree than adaptive selling, corroborating the tenets of self-discrepancy theory. Conversely, prevention-focused salespeople tend to mainly rely on service behaviors as the dominant pathway because they have an overriding need for security by avoiding making unnecessary mistakes and following customers’ explicit needs (Challagalla, Venkatesh, and Kohli 2009). However, to secure consistent performance, prevention-focused salespeople still must learn and practice elements of adaptive selling (Franke & Park, 2006), although adaptive selling appears to be a much less appealing means to goal accomplishment than service behaviors (Higgins, 1998). Finally, the significance of the dual mediation mechanisms of adaptive selling and service behaviors lies in their positive synergistic effect on salesperson performance. It is plausible that service engagement not only better informs adaptive selling strategies (e.g., influence tactics), but it also helps retain customers after customer acquisition (e.g., lower customer attrition), thereby amplifying the overall effectiveness of adaptive selling. Therefore, in our empirical context, we show that the supplemental pathway need not detract from the dominant pathway. On the contrary, they can work in a synergistic fashion, both of which should be actively managed for increased salesperson performance.

Together, our findings contribute to the salesperson regulatory fit literature by clarifying the complementary nature of the underlying dual mediation mechanisms of regulatory foci above and beyond that which has been studied in extant literature. This study adds to regulatory fit theory by showing that not only the dominant pathway characterized by perceived regulatory fit matters, but the supplemental pathway via the less-than-perfect-fit mechanism may also be relevant and can effectively complement effects of the dominant pathway. Moreover, by demonstrating the complex moderating roles of sales controls in a highly competitive psychological climate, this study reveals how theoretically important and managerially relevant boundary conditions can inform both academics and practitioners on how to more effectively manage promotion-focused vs. prevention-focused salespeople.

Managerial implications

The findings of this study also inform perspectives about sales practice regarding both hiring new salespeople and managing the current salesforce. In particular, the results suggest that managers may screen job candidates for appropriate sales positions considering their degrees of promotion vs. prevention focus. For sales jobs that emphasize fast and dynamic change (e.g., high tech industry), adaptive selling is especially critical (Chai et al., 2012). Therefore, hiring salespeople with a high promotion focus has higher potential payoffs. By contrast, when the sales job requires a higher level of effort directed toward service activities (e.g., call center), or deeper attention to service as a core component of relationship building strategies (e.g., B2B sales), a prevention-focused salesperson is a better choice.

From a salesforce management perspective, managers can take a proactive role in shaping salespeople’s motivation to perform adaptive selling or service behaviors. Self-discrepancy theory suggests that an individual’s preferences for a given type of self-guided motivation can be primed as a function of managerial emphasis (Higgins, 1998). That is, it is possible to induce desired salesperson behaviors by enhancing the salience of a certain type of self-guides. For example, a form of leadership known as “error management” explicitly encourages salespeople to make mistakes in return for active learning and improvement of skills (Boichuk et al., 2014). By deemphasizing short-term performance in favor of long-term gains, this type of managerial practice can enhance the salience of ideal self-guides, thereby motivating salespeople to try more adaptive selling by experimenting with a wide variety of selling strategies across situations.

The conventional wisdom in sales management would suggest that competitive psychological climate will motivate salespeople to perform (Brown et al., 1998). However, our results indicate that it also depends on the nature of the sales control system being employed. Managers should use caution when deploying sales controls, especially in a highly competitive sales unit. To nurture the perceived fit of promotion-focused salespeople, managers should grant them maximal degrees of freedom and autonomy in the selling process through the use of outcome control. Moreover, because outcome control typically rewards salespeople based on objective sales outcomes (e.g., dollar amounts), a highly competitive climate will likely motivate promotion-focused salespeople to pursue maximal gains under outcome control. Lacking outcome control, a highly competitive climate cannot effectively motivate promotion-focused salespeople to practice adaptive selling, as the results of this study suggest. By contrast, employing behavioral control in a highly competitive climate is counterproductive because it has the potential to curb promotion-focused salespeople’s motivation to practice adaptive selling. Only when behavioral control is minimal will a competitive climate effectively motivate promotion-focused salespeople to engage in adaptive selling.

For prevention-focused salespeople, managers need to understand that an overriding need for security in the face of intense competition calls for behavioral control, which can provide prevention-focused salespeople with much needed support and feedback during customer encounters, thereby mitigating perceived risks. Behavioral directives reassure prevention-focused salespeople of what and how responsibilities and obligations are supposed to be fulfilled during customer interactions, thereby enhancing their perceived safety and motivating them to meet competitive pressures by resorting to service behaviors (i.e., the ought self-guides). By contrast, outcome control imposed on prevention-focused salespeople is rather threatening because unsatisfactory performance relative to peers becomes especially salient, which further exacerbates their fears of negative outcomes, potentially resulting in lower levels of motivation to engage in service behaviors.

In sum, sales controls can significantly affect perceived regulatory fit in a highly competitive climate, which subsequently alters salespeople’s motivation to perform adaptive selling or service behaviors given their particular regulatory orientations. Sales organizations must carefully consider their managerial practices in light of salespeople’s regulatory foci to ensure, uphold, and protect perceived fit for sustained motivation to perform.

Limitations and future research

Like any empirical research, this study is subject to some limitations. First, although a triadic dataset was collected from three different sources, responses to the independent variables and mediators were from the same source – salespeople. While significant two-way and three-way interactions alleviate concerns of common method bias (Siemsen et al., 2010), future research might collect data from different sources to strengthen the internal validity of the findings. Second, the empirical context is China, which is culturally different from western societies. Therefore, the generalizability of these findings cannot be assumed without empirical testing in other cultural contexts.

This study’s findings also point to promising future research directions. The research focused on the consequences of regulatory foci, but to what extent can regulatory foci be influenced and changed, at least contextually, through managerial actions or organizational culture? Although every salesperson has a baseline level of promotion vs. prevention focus when they are hired, it would be interesting to see whether their regulatory foci undergo adaptation or may be altered to better fit a particular sales environment. In the same vein, because there is a synergistic effect of adaptive selling and service behaviors, sales organizations can benefit by uncovering ways to motivate promotion-focused salespeople to allocate more effort towards service provisions, thereby fully capitalizing on the sales-service synergy therein. Moreover, regulatory fit theory assumes a positive feedback loop such that successful goal achievements resulting from the dominant pathway will reinforce perceived fit overtime. What might happen to perceived fit in scenarios of sales failure? How might salespeople transition from one type of regulatory focus to the other given repeated failure and/or success experiences in the past? What managers may do to help their salespeople navigate through this dynamic process for positive job-related outcomes remains an intriguing area for future research.

Notes

We thank an anonymous reviewer for providing this insight.

This study focuses on the moderation effects of competitive psychological climate on promotion focus–adaptive selling and prevention focus–service behaviors relationships because they are the dominant pathways of these distinct regulatory orientations. However, empirical tests of the moderation effects of competitive psychological climate on promotion focus–service behaviors and prevention focus–adaptive selling relationships (i.e., supplemental pathways) were also conducted; none were found to be significant, nor did they change the statistical significance of hypothesized relationships. In the interest of brevity, these tests were not included in the hypotheses.

Behavioral control can be further partitioned into activity control and capability control, with the former focusing on salesperson activities (e.g., following established procedures and steps) and the latter on skills and capability development (e.g., customer needs discovery questioning techniques). The global behavioral control was used in this study for two reasons: 1) both activity control and capability control can be construed as either supportive or intrusive depending on the salesperson’s regulatory orientation and 2) the three-way interactions of regulatory foci and competitive psychological climate with both activity control versus capability control would make empirical estimations too complex resulting in increased chances of committing Type II errors.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for this insight.

Three firms withdrew from our study during the data collection process.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for recommending chronic regulatory orientation be used as a control variable in our analyses.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for offering this insight.

References

Aaker, J. L., & Lee, A. Y. (2006). Understanding regulatory fit. Journal of Marketing Research, 43(1), 15–19.

Agnihotri, R., Kothandaraman, P., Kashyap, R., & Singh, R. (2012). Bringing “social” into sales: The impact of salespeople’s social media use on service behaviors and value creation. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 32(3), 333–348.

Agnihotri, R., Trainor, K. J., Itani, O. S., & Rodriguez, M. (2017). Examining the role of sales-based CRM technology and social media use on post-sale service behaviors in India. Journal of Business Research, 81, 144–154.

Ahearne, M., Haumann, T., Kraus, F., & Wieseke, J. (2013). It’s a matter of congruence: How interpersonal identification between sales managers and salespersons shapes sales success. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 41(6), 625–648.

Ahearne, M., Jelinek, R., & Jones, E. (2007). Examining the effect of salesperson service behavior in a competitive context. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 35(4), 603–616.

Ahearne, M., Mathieu, J., & Rapp, A. (2005). To empower or not to empower your sales force? An empirical examination of the influence of leadership empowerment behavior on customer satisfaction and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(5), 945–955.

Amyx, D., & Bhuian, S. (2009). Salesperf: The salesperson service performance scale. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 29(4), 367–376.

Anderson, E., & Oliver, R. L. (1987). Perspectives on behavior-based versus outcome-based salesforce control systems. Journal of Marketing, 51(4), 76–88.

Antia, K. D., Mani, S., & Wathne, K. H. (2017). Franchisor–franchisee bankruptcy and the efficacy of franchisee governance. Journal of Marketing Research, 54(6), 952–967.

Armstrong, J. S., & Overton, T. S. (1977). Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. Journal of Marketing Research, 14(3), 396–402.

Avnet, T., & Higgins, E. T. (2006). How regulatory fit affects value in consumer choices and opinions. Journal of Marketing Research, 43(1), 1–10.

Avolio, B. J., Keng-Highberger, F. T., Lord, R. G., Hannah, S. T., Schaubroeck, J. M., & Kozlowski, S. W. (2020). How leader and follower prototypical and antitypical attributes influence ratings of transformational leadership in an extreme context. Human Relations, (in press).

Bliese, P. D. (2000). Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: Implications for data aggregation and analysis. In K. J. Klein & S. W. J. Kozlowski (Eds.), Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations: Foundations, extensions and new directions (pp. 349–381). Jossey-Bass.

Boichuk, J. P., Bolander, W., Hall, Z. R., Ahearne, M., Zahn, W. J., & Nieves, M. (2014). Learned helplessness among newly hired salespeople and the influence of leadership. Journal of Marketing, 78(1), 95–111.

Bolander, W., Chaker, N. N., Pappas, A., & Bradbury, D. R. (2021). Operationalizing salesperson performance with secondary data: Aligning practice, scholarship, and theory. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 1–20.

Brendl, C. M., Higgins, E. T., & Lemm, K. M. (1995). Sensitivity to varying gains and losses: The role of self-discrepancies and event framing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(6), 1028–1051.

Brown, S. P., Cron, W. L., & Slocum Jr., J. W. (1998). Effects of trait competitiveness and perceived intraorganizational competition on salesperson goal setting and performance. Journal of Marketing, 62(4), 88–98.

Byron, K., Peterson, S. J., Zhang, Z., & LePine, J. A. (2018). Realizing challenges and guarding against threats: Interactive effects of regulatory focus and stress on performance. Journal of Management, 44(8), 3011–3037.

Chai, J., Zhao, G., & Babin, B. J. (2012). An empirical study on the impact of two types of goal orientation and salesperson perceived obsolescence on adaptive selling. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 32(2), 261–273.

Chamberlin, M., Newton, D. W., & Lepine, J. A. (2017). A meta-analysis of voice and its promotive and prohibitive forms: Identification of key associations, distinctions, and future research directions. Personnel Psychology, 70(1), 11–71.

Challagalla, G. N., & Shervani, T. A. (1996). Dimensions and types of supervisory control: Effects on salesperson performance and satisfaction. Journal of Marketing, 60(1), 89–105.

Churchill Jr., G. A., Ford, N. M., Hartley, S. W., & Walker Jr., O. C. (1985). The determinants of salesperson performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marketing Research, 22(2), 103–118.

Cravens, D. W., Ingram, T. N., LaForge, R. W., & Young, C. E. (1993). Behavior-based and outcome-based salesforce control systems. Journal of Marketing, 57(4), 47–59.

Cron, W. L., Alavi, S., Habel, J., Wieseke, J., & Ryari, H. (2021). No conversion, no conversation: Consequences of retail salespeople disengaging from unpromising prospects. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 49(3), 502–520.

Crowe, E., & Higgins, E. T. (1997). Regulatory focus and strategic inclinations: Promotion and prevention in decision-making. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 69(2), 117–132.

DeCarlo, T. E., & Lam, S. K. (2016). Identifying effective hunters and farmers in the salesforce: A dispositional–situational framework. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44(4), 415–439.

Demerouti, E., & Bakker, A. B. (2011). The job demands-resources model: Challenges for future research. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 37(2), 01–09.

Dimotakis, N., Davison, R. B., & Hollenbeck, J. R. (2012). Team structure and regulatory focus: The impact of regulatory fit on team dynamic. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(2), 421–434.

Dong, Y., Liao, H., Chuang, A., Zhou, J., & Campbell, E. M. (2015). Fostering employee service creativity: Joint effects of customer empowering behaviors and supervisory empowering leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(5), 1364–1380.

Fang, E., Palmatier, R. W., & Evans, K. R. (2004). Goal-setting paradoxes? Trade-offs between working hard and working smart: The United States versus China. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 32(2), 188–202.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

Franke, G. R., & Park, J. E. (2006). Salesperson adaptive selling behavior and customer orientation: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marketing Research, 43(4), 693–702.

Freitas, A. L., & Higgins, E. T. (2002). Enjoying goal-directed action: The role of regulatory fit. Psychological Science, 13(1), 1–6.

Friedman, R. S., & Förster, J. (2001). The effects of promotion and prevention cues on creativity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(6), 1001–1013.

Fu, F. Q., Richards, K. A., Hughes, D. E., & Jones, E. (2010). Motivating salespeople to sell new products: The relative influence of attitudes, subjective norms, and self-efficacy. Journal of Marketing, 74(6), 61–76.