Abstract

This systematic review of sponsorship-linked marketing from 1996 to 2017 analyzes the current state of research. The overarching conclusion is that there is a surplus of research that examines audience responses to sponsorship-linked marketing but a shortage of research that examines marketing management of the sponsorship process. This misalignment of research needs to research investments stems partly from a failure to consider the sponsorship process as a whole. Research has failed to account for the complexity of the sponsorship-linked marketing ecosystem that influences both audience response and management decision making. The authors develop a sponsoring process model, generalizable to all sponsorship contexts, as an organizing frame for the review and as a reorienting perspective for research and practice. To spur future work, they advance a series of research questions and, to support practice, provide managerial insights.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Television advertising’s move from being discussed as “traditional media” to being called “legacy media” marks the long-predicted death of advertising as mass media (Rust and Oliver 1994). In place of mass-media advertising is a dazzling array of “indirect” marketing approaches (Cornwell 2008), including sponsorship, product placement, and influencer marketing. Sponsorship of sports, the arts, charity, and entertainment has emerged as a meaningful component of brand strategy (Cliffe and Motion 2005). Academic articles have followed this evolution in marketing practice, though research still has little in the way of comprehensive frameworks. The failure to advance comprehensive conceptualizations of sponsorship can partly be attributed to its long treatment as advertising, which deserves rethinking. Worldwide advertising spending was predicted to reach $628 billion in 2018 (eMarketer 2018), and outside this figure, worldwide sponsorship spending is likely to have exceeded $65 billion (IEG 2018). Importantly, for every $1 invested in sponsorship rights, $2.20 is spent on sponsorship-related advertising and promotion (IEG 2016). Sponsoring is a multifaceted strategic decision that is accompanied by advertising spending, and research has not invested adequately in understanding the sponsoring process.

This work has two overarching goals. The first is to introduce the topic and map current research through the organizing frame of the sponsorship process and, in doing so, reorient future research. The clear surplus of research on audience response to sponsorship-linked marketing and the shortage of research on marketing management of the sponsorship process suggest the need for a comprehensive model that allows generalizations about what is known. Included in this is the importance of ecosystems, boundaries, and complex interrelationships. The second goal is to offer theoretically grounded questions to spur interest in under-researched topics and to support practitioners with management insights.

Sponsorship-linked marketing and prior reviews

Sponsorship is “a cash or in-kind fee paid to a property (typically in sports, arts, entertainment, or causes) in return for access to the exploitable commercial potential of that property” (IEG 2017). Sponsoring has been thought of as a marketing alliance in which two or more brands are visibly linked in a product context (Farrelly and Quester 2005). In sponsoring, the alliance is between a brand (company or organization) and another brand (entity or organization), typically referred to as a property (short for “property rights holder”). In practice, the term “partnership” is often used, but for clarity we use the term “sponsorship” herein to distinguish this contract-based relationship from other partnerships, such as joint ventures or cobranding. The term “sponsorship-linked marketing” represents the marketing activities pursuant to a sponsorship contract that then form a marketing platform.

It is argued that research in sponsorship is siloed across disciplines and is disconnected. Thus, as mentioned, a goal of the current work is to identify important linkages that give rise to a clearer picture of needed research, and this begins with a review of review articles (see Table 1). Early systematic reviews of sponsorship research included 80 articles as of 1996 (Cornwell and Maignan 1998) and 233 articles in 2001 (Walliser 2003). Both of these reviews tried to establish the research worthiness of the fledgling area and have, based on citations (997 and 511 in Google Scholar, respectively, as of February 2019), influenced the development of subsequent research. Other reviews have followed.

In 2012, Walraven et al. published a narrative review limited to sponsorship brand equity effects, and in 2015, Kim et al. conducted a review that considered sponsorship effects from a consumer perspective. The Walraven et al. work is not based on a systematic retrieval of literature and is limited to only sport, and therefore we do not consider it further, but the Kim et al. review is discussed subsequently in more detail. One point however, is worth bringing forward from the Kim et al. (2015) meta-analytic review, and that is, across 58,469 participants, from 164 independent samples, drawn from 154 studies, these authors could identify only one empirical generalization: “Our results reinforce the extant literature about fit [that it is consistent in its ability to impact sponsorship outcomes], while also showing that with the exception of fit, sponsor- and sponsee-related antecedents have differential effects across different sponsorship outcomes” (p. 420). This finding has less to do with the profundity of fit (which has not been challenged by the use of control variables, e.g., length of relationship, overlapping values, in most studies), and more to do with the attractiveness of this empirical regularity in producing statistical significance. Importantly, in this finding, the Kim et al. (2015) review discloses the narrowness of sponsorship research.

In 2015, Johnston and Spais published a content analysis of the abstracts of 841 articles in sponsorship and found that, semantically, they are intellectual, strategic, behavioral, and relational. That work describes sponsorship in terms of semantic representation but does not motivate future research. In 2017, Jin published a content analytical review of 282 articles appearing in the International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship. This review comingles research on sponsorship and sports marketing and therefore does not offer a clear focus on sponsorship. Other conceptual works in specific areas such as memory in sponsorship (Cornwell and Humphreys 2013) or effectiveness of consumer-focused sponsorship (Cornwell et al. 2005), have contributed to research in sponsorship but have perhaps inadvertently narrowed the research frame through their focus on consumer information processing. The aim of the current review is to widen the aperture on sponsorship-linked marketing.

Review frame and approach

Given the interdisciplinary nature of research on sponsorship, this review sought a broad lens by beginning the search with terms of interest and then narrowing to journals represented in the 2017 Web of Science Journal Citation Reports (WS-JCR). In this systematic review (following suggestions by Littell et al. 2008), search terms were of two types: central topic terms, including “sponsor,” “sponsorship,” “sponsoring,” “partnership,” “partner,” and specific topic terms, including “ambushing,” “ambush marketing,” “leverage,” “leveraging,” “activation,” “activational,” and “exclusivity.” In addition, we used forward and backward citation analyses to identify additional articles, particularly in areas such as sport, art, entertainment, and charity. Excluded from this search were white papers, conference papers, and abstracts. This search expansion phase resulted in 1161 total articles from 1996 to 2017. We selected these years for the review as the 20 years since the most cited review article with a frame that ended in 1996 (Cornwell and Maignan 1998). The value of this expansive search was that it brought into evaluation articles in a broad range of publication outlets with varied terms and keywords.

In the second phase, we limited articles for review by selecting only the outlets appearing in the 2017 WS-JCR. Limiting the review in this way provided a known level of citations, publication frequency, a clear understanding of journal hosting, and a quality indicator not dependent on reviewing author judgment (Tranfield et al. 2003). Use of this filter resulted in 409 articles in the final review. These articles were mainly from European Journal of Marketing, International Journal of Sports Marketing & Sponsorship, International Journal of Advertising, Journal of Advertising, Journal of Advertising Research, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Journal of Business Research, Journal of Sport Management, Psychology & Marketing, and Sport Management Review. Though constituting fewer articles, other major marketing journals, including Journal of Consumer Research, Journal of Marketing, and Journal of Marketing Research, were represented. The frequency of these journals in the review increased in the second decade. Moreover, articles appearing in Journal of Sponsorship (active from 2008 to 2011), Journal of Product and Brand Management, and Sport Marketing Quarterly contributed to the overall volume of publications identified in the expansion phase but were ultimately excluded from the final review frame because they are not in the 2017 WS-JCR. This filter, however, retained contributions from Journal of Sport Management and Sport Management Review, which are arguably the top two journals in sport management. Their representation is important because 70% of sponsoring is in sport (IEG 2018).

Our first broad analysis stems from a primary categorization of publications into three areas (1) reviews and trends (including policy discussions) in sponsorship (26 publications), (2) management and strategy in the sponsorship process (101 publications), and (3) measurement and effectiveness related to target audience response (282 publications). This analysis (presented in Fig. A1 in the Web Appendix) reveals that in terms of substantive content, the central shortage is in sponsorship management and the central surplus is in audience response. A subsequent analysis across all topics found that publications considering consumers (236) dominated all other topics (173). This does not mean that audience response and consumer orientation are not worthwhile but that these areas have been focal in establishing the value of sponsoring to the point of excluding more fundamental process management research. Web Appendix Fig. A1 also documents academic interest in sponsorship, showing the annual growth in sponsorship research, with steady growth punctuated by special issues.

Subsequently, we reviewed publications and then grouped them into six broad categories: decision making, target audiences, objectives, measurement, context, and external forces. Next, we further cross-referenced these groupings for secondary themes. For example, following an iterative review of the content of the “decision making” grouping, “initial decision” and “subsequent decision” formed new topics. We repeated this process for all six categories. Subsequent analysis was then dictated by the nature and extent of the literature, as well as the comprehensiveness prior reviews. Some sections had so few articles that we used a narrative synthesis (Collins and Fauser 2005) to introduce interesting but overlooked topics. Areas with more studies are addressed with comprehensive supporting tables.

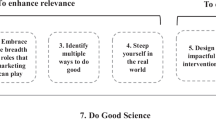

Sponsoring process model

The sponsoring process model in Fig. 1 is an outgrowth of our iterative analysis as well as the application of ecosystems theory to the sponsorship context. Because sponsorship links business and nonbusiness entities, we adopt Mitleton-Kelly’s (2003, p. 30) social ecosystem view of each organization as “a fully participating agent which both influences and is influenced by the social ecosystem made up of all related businesses, consumers, and suppliers, as well as economic, cultural, and legal institutions.” In the following sections, we describe how three tenets common in ecosystems theorizing—namely, interconnectedness, boundedness, and dynamism—apply to sponsoring and inform the sponsoring process model of Fig. 1.

First, recognizing the interconnectedness and dependence of system members for success and survival (Peltoniemi and Vuori 2004), any model of the sponsoring process must represent both the sponsor and sponsee perspectives. Research on sponsoring has been criticized for primarily considering the perspective of the sponsor (Toscani and Prendergast 2018). This imbalance, which underrepresents sponsorship research from the property side, necessarily persists as we review previously conducted research. Sponsees are for-profit and nonprofit entities in sport, the arts, entertainment, and charity that should also be the focus of business research. In keeping with Mitleton-Kelly’s (2003) view of shared influence, Fig. 1 depicts process elements relevant to the sponsor in the top half of the model and process elements relevant to the sponsee in the bottom half of the model, with many elements overlapping.

Second, the model recognizes that any sponsorship decision resides within boundaries. From an ecosystem theory perspective, the boundaries may not be clear-cut or even stable but should be relevant to the context of study (Peltoniemi and Vuori 2004). Boundaries are characterized here as local, regional, national, and international (Fig. 1). Because sponsoring is a market behavior in which brands target audiences, sponsorships typically are parallel to the sponsor’s markets of interest. Thus, local brands with limited geographic reach typically have local partnerships. National brands may amalgamate markets to gain national coverage. International brands may also amalgamate regional and national sponsorships to form a portfolio or choose international events such as the Olympics or World Cup. Importantly, the interdependent and interconnected nature of sponsorship due to exclusivity agreements and geographic boundaries is an under-researched aspect of these relationships.

Last, complex systems such as those found in sponsoring are always discussed as dynamic, with both endogenous (e.g., number of professional teams in a city) and exogenous (e.g., perceptions of professional sports) dynamics influencing system effects (Anggraeni et al. 2007). The model in Fig. 1 includes six columns representing a generalized sponsoring process and chronology and is surrounded by constructs contributing to the understanding of the process and outcomes. We address these aspects in subsequent sections. Of note, while dynamism can take many forms, the recursive nature of sponsoring is at the fore. Within a bounded, interconnected ecosystem, the sponsorship process repeats, and outcomes at one stage become inputs to other stages and decisions. For example, a regional arts museum ends a partnership with a regional bank after many years but cannot attract a new bank sponsor because of the belief that the museum is too well associated with the previous bank.

Importantly, this model is the first to advance a generalizable, holistic concept of the sponsoring process from an ecosystem perspective (Mitleton-Kelly 2003) and to treat sponsorship as interconnected, bounded, and dynamic. As noted, research has emphasized the sponsor perspective and has built on several sponsorship effects models (e.g., Cornwell et al. 2005; Speed and Thompson 2000). Also available are concept-specific models of sponsoring (e.g., competitive advantage, Fahy et al. 2004), industry-specific models (e.g., tourism, Lamont and Dowell 2008), aspect specific (e.g., sponsorship evaluation O’Reilly and Madill 2012) and organization-specific models (e.g., nonprofit, Doherty and Murray 2007), these models are partial and particular, not generalizable.

The following sections follow the sponsoring process model of Fig. 1. Each section begins by identifying essential concepts and constructs, current or needed in sponsorship research, before examining interrelationships and posing research questions. Priority in each section is given to research questions addressing under-researched topics in sponsorship management.

Initial decision in sponsorship relationship

The link between sponsor and property is typically contractual and, for sports, arts, and entertainment properties, is typically the result of negotiations. Properties such as sport teams and music festivals are unique, with particular geographic orientations, audiences, and marketing-related potential in their ecosystems. In the two decades of the review, the dominant theoretical view of sponsorship has been one of exchange (McCarville and Copeland 1994), in which properties sell a variety of “assets” that may be of interest to a sponsor. For example, in the initial decision to sponsor, a marathon would typically have, at a minimum, the assets of “title” sponsor and official product/service sponsors to exchange with a brand for their financial or in-kind support. While the orientation to exchange may persist, it must be subject to a broader understanding of the relevant ecosystem.

Sponsorship is a source of financing for most properties, and therefore properties solicit potential sponsors. For this reason, the initial relationship is the first column of Fig. 1. This does not mean that objectives and target audiences for a sponsorship relationship are not addressed before an agreement is reached but that the typical sponsorship is unlike the typical marketing communications process in which marketers initiate the process and have a blank slate from which to work. Property assets may be combined in levels of sponsorship or packages and offered to sponsors depending on their goals and objectives in the partnership. While case studies from the sponsor perspective (e.g., telecommunications brand O2, Cahill and Meenaghan 2013) and the property side (e.g., university athletics program, Long et al. 2004) detail strategic choices in sponsorship, research on sponsorship asset pricing, deal characteristics, and contract price setting is minimal.

Before addressing these three basic aspects of the initial sponsorship relationship, we introduce one theoretical construct, agency effects, and one concept in sponsorship deal making, exclusivity, that hold implications for the initial relationship.

Agency effects

A long-time concern in sponsoring is that decision making is overly influenced by individuals who, when operating as agents for their organization, choose relationships that benefit them rather than their organization (Clark et al. 2002, 2009; Long et al. 2004). Concern about this phenomenon, known as agency effects, has lessened as sponsorship has become strategic and accountable but has not entirely died away, particularly not in the arts (Daellenbach et al. 2013). In addition, sponsorship decision making within an ecosystem boundary may be suboptimal through constraints attributed to agency effects. For example, a regional auto dealer may view its ideal sponsorship as the single professional sport in the city it serves, but if this relationship is already taken by another auto dealer, it is left to pursue its second-best choice. Sponsorships, as cooperative business agreements, are fertile ground for agency effects (see Eisenhardt 1989), and to date, systematic evaluation of the extent to which agency effects influence sponsorship decision making is negligible.

Exclusivity

A central concept in the initial sponsor–sponsee relationship is exclusivity, or whether the sponsoring brand is the only brand officially associated with the event/activity in the product/service category. Exclusivity in sponsoring has historically had advantages over traditional advertising, in which more than one brand in a category might be present in the medium. Exclusivity is thought to limit audience confusion (Sachse et al. 2009) and is listed by sponsors as the most valuable benefit of sponsorship, ahead of on-site signage and broadcast advertising opportunities (IEG 2015). Exclusivity naturally limits the number of sponsors for an event, with the possibility that some sponsors are unable to find an available slot with a property of interest. Thus, properties have advanced the concept of “shared exclusivity,” in which brands that are not direct competitors (e.g., luxury auto and economy auto) sponsor the same property at the same time. This, in turn, allows properties to sell more slices of the sponsorship pie.

The contractually enforceable concept of exclusivity (Ellis et al. 2011) is inextricably linked to sponsorship ecosystem boundaries and behaviors, such as ambushing (the marketing behavior of brands attempting to associate with an event or activity without being an official sponsor). This market behavior arises from contracted exclusivity; the brand misses out on being an official sponsor and engages in ambush marketing to link to the property. Thus, exclusivity is central in lawsuits addressing ambushing (Cobbs 2011a). In terms of ecosystem boundaries, exclusivity forces properties to search for and secure sponsors across industries, which may lead to clutter from an increased number of total sponsors, thus reducing sponsorship efficiency (Walraven et al. 2016).

Asset pricing

Property rights holders have little guidance on deciding the price for stadium naming rights, for example, or for being the official snack of an event. Team and events are often encouraged to develop an inventory of their assets (e.g., event, halftime shoot-out) and to price these assets not to cover cost but at market value. Asset values may be determined through comparison to other similar assets held by other properties, but this process is imprecise given the uniqueness of properties. Asset pricing generally informs the asking price in sponsorship. Asset pricing is thought to be influenced by the ability of the property to provide exclusivity and is subject to negotiation. Asset pricing has not been a focus of research.

Deal characteristics

In sponsoring, contracts set the duration of the relationship, payments (cash or in-kind), exposure values (e.g., signage) tickets, access to celebrities, hospitality booths, and consider other values such as fit between the partners in the exchange. While studies frequently include deal characteristics, they often fail to provide a comprehensive consideration of them. The most examined deal characteristic is contract duration (the agreed-on time partners will work together under a legally binding contract), and long contracts tend to be associated with favorable outcomes, such as better recall and recognition of sponsors (Cornwell et al. 2001). Another deal characteristic stemming from the partners in combination is geographic distance (the physical distance from the sponsor to the property). A general finding is that deals with distant sponsors are less well received by audiences (Clark et al. 2002; Olson and Thjømøe 2011). Woisetschläger et al. (2017) examine the extent to which sponsorship contract length, fees, distance, fit between the sponsor and the property, and the type of sponsorship influenced audience perceptions of sponsors. High sponsorship fees and distant international sponsors were associated with perceptions of calculative motives. This suggests that a cultural aspect to sponsorship ecosystems holds meaningful consequences, but this topic is under-researched.

Price setting

Few studies examine deal price setting in sponsorship, and none examine price negotiation explicitly. Two articles have somewhat similar findings and are based on secondary data. Gerrard et al. (2007) use 112 naming rights deals to examine the valuation of stadium naming and find that price is related to size of potential target audiences, facility capacity, status of resident teams, and the diversity of facility usage. They also observe a price premium for new sites with no previous naming rights association. Wishart et al. (2012), using a sample of 300 publicly available sponsorship proposals across sports, arts and charity, find that while media coverage and attendance drive asking price, access to property offerings, such as celebrities, also influences price. They also suggest that other factors, such as relationship quality (e.g., positive experience working together), can drive the final negotiated price. However, neither study examines the price-setting process in its entirety.

Research on sponsorship pricing is scant, and no study has tried to understand how geographic ecosystem boundaries limit the number and nature of available relationships. Sponsorship deals typically begin with asset pricing by the property that in turn influences asking price. Final deal characteristics are reached through negotiation with the potential sponsor. In this process of price setting, two generalizable tenets could be tested. The first is that agency effects persist, and the second is that exclusivity, as one of the most important characteristics sought by sponsors (IEG 2015), is valued and will command a higher price.

RQ1:

In sponsorship price setting (where asset prices and deal characteristics are negotiated), does the presence of agency effects (benefits accruing to decision makers rather than to their organizations) negatively influence sponsorship value to the organizations?

RQ2:

For comparable assets (e.g., those having similar characteristics, such as audience reach), are deals having exclusive sponsorship rights associated with higher rights fees and better outcomes than deals having shared exclusivity, and in turn, do both have higher rights fees and better outcomes than nonexclusive deals?

As discussed, the “Sponsorship Relationship” of Fig. 1 represents the contractual agreement that outlines how the parties will work together and any exchange of assets. This simplified model shows a focal relationship, but this resides within a complex relational ecosystem involving many parties, and this larger network of connectivity in sponsorship is also represented by the other properties the sponsor holds (portfolio of sponsorships) and the other sponsors a property holds (the roster of sponsors). The vast majority of research to date considers sponsorship relationships between one sponsor and one property and does not examine the influence of the relevant ecosystem on the sponsoring process.

Sponsor portfolios and property rosters

Though potentially profound in implications, limited research has examined how the decision to sponsor or be sponsored is influenced by existing and past sponsorship relationships of the brand and existing and past relationships held by the property. From an integrated marketing communications theory perspective, brand management should be holistic; therefore, strategy and practice must take all consumer touchpoints into account (Madhavaram et al. 2005). Thus, this section examines integration within and across these two groupings (portfolios and rosters) that result from the sponsoring process. Figure 1 depicts the portfolio of sponsorships held by the brand and the roster of sponsors a property has as influencing the initial sponsorship decision. Given this under-researched area, Table A1 in the Web Appendix details the articles within this research frame that address portfolios and rosters.

Portfolios

A sponsorship portfolio is “the collection of brand and/or company sponsorships comprising sequential and/or simultaneous involvement with events, activities and individuals (usually in sport, art and charity) utilized to communicate with various audiences” (Chien et al. 2011, p. 142). For example, the sport drink brand Gatorade holds hundreds of partnerships with groups such as the National Football League and the National Basketball Association as well as marathon events, international soccer, and auto racing, to name a few. The brand links to team sports most significantly through its signature ritual, the Gatorade dunk, which involves pouring a mixture of Gatorade and ice from a branded barrel over the winning coach after a game. Brands such as Gatorade may have a wide market audience (anyone who would drink a sports drink) but a narrow message (“recovery after sports” theme) that is communicated by various sport sponsorships. These combined elements of a portfolio influence brand image and, in turn, brand equity of the sponsor (Chien et al. 2011, Groza et al. 2012). This is accomplished through repeated presentation of brand associates across sports that support contextual learning.

Research in sport shows that brand managers wanting to develop sponsorship portfolios that reach target audiences with brand-consistent messages must recognize interactions between their brand, as a sponsor, and the milieu of the sponsorship context (Chanavat et al. 2009, 2010). Research in music suggests that even the size of a portfolio can hold sway over consumer response to the sponsor (Bruhn and Holzer 2015). At the extreme, brands create their own events, such as what Red Bull energy drink has done in staging a space jump and sport-themed, but brand controlled, events aligned with auto racing and winter sports. Evidence shows that sponsorship policies regarding portfolio development somewhat align with corporate mission statements. For example, Cunningham et al. (2009) find that companies focused on financial success are more inclined to engage in sponsorship of individual athletes, while those focused on employees favor team sports. Theory on the difference in perceiving groups versus individuals (Hamilton and Sherman 1996) argues that this is due to both expectations of unity and coherence (e.g., Did everyone on a team contribute to the win?) and related information processing and judgments. This suggests that sponsorship portfolios can serve to express corporate values but also to orient consumers to current marketing messages.

RQ3:

What portfolio characteristics (e.g., types of sponsorships held) and what level of portfolio integration (e.g., brand consistent messaging) result in the highest brand value from sponsoring?

Rosters

On the property side of partnerships is a roster—a list of sponsors (Ruth and Simonin 2006) similar to that of the sponsor portfolio of properties. For example, any one sponsor for an event or activity interacts with cosponsors to influence sponsorship perceptions and outcomes (Carrillat et al. 2010), with outcomes differing depending on the congruence of the roster (Carrillat et al. 2015). Ruth and Simonin (2003) examine the influence of multiple sponsors on the sponsored event and find that having a controversial product such as tobacco in the roster of sponsors for a parade harmed attitudes toward the event and, in turn, brand equity. This finding could be a concern for soft drinks, “junk” food, firearms, and betting.

Just as portfolio size is important to the sponsor, roster size is important to the property, because large rosters can influence perceptions of goodwill (Ruth and Simonin 2006), though negative implications of large rosters can be offset by involvement in the event (Ruth and Strizhakova 2012). Similar concerns have been raised in other contexts to which we aim to generalize. For example, endorsers often have a list of endorsement contracts that influence perceptions of the human brand such as an athlete or entertainer (Kelting and Rice 2013).

Less developed thinking has occurred in the design of property rosters relative to that of sponsor portfolios, but there is a better understanding of rosters as extended relationships in an embedded social system (Berrett and Slack 2001). In considering the extent to which a sport organization’s sponsor relationships influence the amount of financial support attracted, Pieters et al. (2012) provide evidence that network embeddedness (measured as the extensiveness of ties, particularly those with sponsors) is beneficial to financial performance.

As previously discussed, exclusivity means that properties will naturally seek sponsors across a wide variety of industries. There is, however, still the potential to develop an orientation in which the roster works well together. For example, NASCAR’s “Fuel for Business Council” brings sponsors together to create networking opportunities for partners and is part of a growing trend of business-to-business (B2B) networking councils (IEG 2016b). Although sponsor rosters, or even B2B councils created for them, do not rise to the level of formality as interorganizational relationships of an alliance (see Todeva and Knoke 2005), their role constitutes an economic organization of production (Ghoshal and Bartlett 1990). This perspective suggests that thoughtful composition and active management of a roster should be value adding for each participating sponsor and, in turn, for the property.

RQ4:

Does active roster integration (such as found in B2B relationship building) on the part of the property increase sponsorship value for the sponsors and the property?

Note that the sponsor’s portfolio and the property’s roster are being recognized as part of a network and, thus, an ecosystem. The evolution of sponsoring, from philanthropy to market and management oriented, to network based (Cobbs 2011b; Ryan and Fahy 2012), suggests ever more emphasis on the management values of these extended relationships. Olkkonen (2001) advocates for an interorganizational network frame in international sponsorship research with a focus on the field of sponsors, sports, media, and public broadly defined. Nonetheless, for the most part, research has not considered the influence of the overall network. One exception provides an ideal example of how important a larger frame is to the study of sponsorship. Yang and Goldfarb (2015) examine the possibility of banning controversial products, alcohol, and gambling from English soccer sponsorship. Using a two-sided matching model, they show that clubs having these controversial sponsors, if lost from a change in policy, would not be the most affected by the change; rather, the more successful teams would poach the sponsors of low-attendance/low-income area teams, leaving them without sponsors. Bice (2018) makes a similar argument in the relationship between junk food and soft drink bans and the funding of youth sports programs but does not investigate this further. Therefore, underlying the following question is that these overall networks are important.

RQ5:

Do sponsorship portfolios in combination with property rosters, as part of an integrated network, influence sponsorship outcomes for the sponsor, sponsee, and their audiences?

Given decades of sponsorship-linked marketing practice, past sponsor portfolio members and past property roster members can influence current sponsorship outcomes, and we revisit this when addressing sponsorship extensions and terminations. Importantly, the conceptual connectivity (in terms of links among sponsorship participants) and complexity (in particular the multilayered ways sponsorship participants might be involved) that sponsorship holds for brands and properties requires considering the entirety of the sponsorship process. In summary, research is limited on portfolio and roster effects in sponsorship and on how these form part of an overall network within an ecosystem.

Target audiences

This subsection on target audiences and the following two on objectives and engagement represent the heart of sponsorship-linked marketing platforms (see second, third, and fourth columns of Fig. 1). As noted, effectiveness in reaching consumer audiences is the most researched topic in sponsorship. We summarize a previously conducted meta-analysis (Kim et al. 2015) as a jumping-off point for further research. The goal is not to delineate the nature of sponsorship influence on audiences (myriad works have done that) but to identify under-researched topics. We begin by considering the top audiences for sponsorship—namely, consumers (e.g., fans, participants), employees, and organizational/market audiences (e.g., shareholders). Other audiences such as governments, nongovernmental organizations, and channel members, as Fig. 1 notes, may be influenced by sponsorship but are less frequently directly targeted. Emphasis is given to employees as an under-researched audience of size and influence. We then briefly introduce the current state of research on objectives and engagement in sponsorship. The section concludes with reflection on the complexity of target audiences and on how adopting an engagement ecosystem perspective could address these challenges.

Individuals as consumers

Consumer-based brand equity captures the differential effect of brand knowledge on consumer response to the marketing of a brand (Keller 1993), and sponsorship is a contributor to both brand awareness and brand image that create this response. The construct of consumer-based brand equity, though employed primarily by for-profit brands, applies equally well to properties. Given researcher interest in audience response to sponsorship, Kim et al. (2015) conduct a systematic meta-analysis to gain insight into factors influencing outcomes. Findings from 154 studies involving 58,469 participants from 164 independent samples showed that sponsor-related antecedents (exposure, sponsor motive, ubiquity, leverage, articulation, and cohesiveness), the dyadic antecedent of fit or congruence between the sponsor and sponsee, and sponsee-related antecedents (identification, involvement with the property (e.g., here, involvement by the individual with the sport), and prestige) have a broad range of effects on cognitive, affective, and behavioral outcomes. The most important findings show that perceptions of sponsor motives (e.g., self-serving or sport-serving) hold the most sway over affective outcomes, that fit between the sponsor and sponsee exerts a positive impact on sponsorship outcomes, and that involvement with the property has the strongest influence on behavioral outcomes.

Kim et al.’s (2015) findings also illuminate several methodological factors that moderate the relationships between antecedent and outcomes. In particular, using actual brands in research yields stronger effect sizes than using fictitious brands. While fictitious brands offer more control in research, as the only information about them is that contained in the study exposure, they do not afford the powerful influence that actual brands do. Furthermore, differences implied that nonstudent samples might be preferable to student samples. This finding is likely due to students’ similarity across many characteristics, and therefore studies employing student samples may have restricted variance.

Finally, Kim et al.’s (2015) meta-analysis, which included publications from 1982 to 2013, did not explore consumer product category involvement, competitor activities (e.g., ambushing), or sponsor exclusivity arrangements, owing to insufficient availability of primary studies. They also rightly note that because the meta-analytic approach is restricted to only constructs having been investigated, the framework used in their study represents not the most critical constructs per se but those most widely researched. In the database we use herein, we identified an additional 85 consumer-focused studies published since 2014. While more recent research on consumer-focused outcomes could be described as more sophisticated (e.g., Plewa et al. 2016), it generally continues along already-established trajectories.

Researcher interest in consumer-focused sponsorship objectives has resulted in a surplus of articles. One orienting model dominating this research examines sponsorship exposure as leading to brand outcomes, moderated by individual (e.g., involvement) and dyadic (e.g., congruence between the sponsor and the sponsored) factors. Unfortunately, the vast majority of these studies do not include prior brand exposure, attitude, or behavior and thus may overestimate the contribution of sponsorship to marketing objectives. An exception is Lee and Cho (2009), who show that prior brand attitude affects sponsor attitude and purchase intent (see also Carrillat et al. (2005) and Mazodier and Merunka (2012) for brand awareness pretesting). By contrast, Cho et al.’s (2011) longitudinal panel study offers evidence that Coca-Cola’s Olympic sponsorship generated significantly higher choice for Coke than Pepsi after controlling for sales related to advertising. A large-scale study of German soccer fans also finds a positive influence of sponsoring from team exposure (Woisetschläger et al. 2017). Still, empirical evidence of the contribution of sponsoring to brand outcomes beyond priors is limited.

Employees

Internal audiences for sponsorship are also relevant to sponsorship decision making (Khan and Stanton 2010) and investment, and while often mentioned (e.g., Zinger and O’Reilly 2010), have not been a central focus of researcher attention. An obviously important construct in the relationship between an employee and the sponsorship partnership is employee organizational identification, but many job-related behaviors can be considered. Long heralded as a key construct in management theory, organizational identification captures the extent to which employees incorporate the organization’s identity into their own identity and the extent to which this is important to their self-definition (Ashforth et al. 2008; Dutton et al. 1994).

Sponsorships oriented to employees may have the goal of developing esprit de corps (Farrelly and Greyser 2007) or may be employed systematically in an internal marketing program (Farrelly et al. 2012). Khan et al. (2013) find that employee attitudes toward sponsorship support favorable attitudes toward the organization and positive extra-role behaviors known as citizenship behaviors. Sponsorship can also help link an internal marketing program to an external marketing program. For example, Plewa and Quester (2011) report that sponsorship leveraged by corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities can result in staff motivation, satisfaction, and retention, leading to consumer satisfaction, purchases, and retention.

Theoretical work from management (Cornwell et al. 2018) argues that firm and property horizontal marketing relationships hold the potential for both positive and negative organizational identification outcomes. For example, employees might consider the horizontal partnership relevant to their own sense of self and congruent with their understanding of their firm; alternatively, they could view this same partnership as irrelevant or even in conflict with their self-concept and view of their employer. According to the authors, sponsorship could support identity expression/confirmation or identity resignation/violation. Thus, further empirical research is required to better understand not that sponsorships influence organizational identification and citizenship behaviors but how. Thus:

RQ6:

Do sponsorships that allow expression or confirmation of employees’ sense of identity result in higher levels of organizational identification and citizenship behaviors?

Organizational/market audiences

Figure 1 depicts several organizational and market audiences for sponsorship. Save for shareholders in financial markets, few studies have considered more macro audiences for sponsorship relationships (e.g., host country audiences Nadeau et al. 2016). Lee et al. (2013), in developing a measure to capture the social impact of sport sponsorship, take a holistic view of audiences that includes the business firm as sponsor, government and nongovernmental organizations, and the property. Research on B2B sponsorship values is also limited (exceptions include Athanasopoulou and Sarli 2015; Clark et al. 2003; Farrelly and Quester 2003a). We found a surplus of studies examining shareholders in financial markets as a bellwether of sponsorship value. Several event studies have examined factors related to abnormal stock returns (e.g., Clark et al. 2002, 2009; Cobbs et al. 2012; Cornwell et al. 2005; Mazodier and Rezaee 2013). Across these studies, findings were divergent (abnormal positive and negative returns and also nonsignificant findings). Within the frame of this review, we found 19 event studies; thus, this area may benefit from a meta-analytic review.

Objectives

The contract between the sponsor and property is typically built around objectives such as brand awareness, image and personality, loyalty, and goodwill (Cliffe and Motion 2005) that the sponsor aims to enhance among audiences of the property through activities (see the third column of Fig. 1). Objectives in sponsorship can be affective, cognitive, or behavioral (Cornwell et al. 2005). For example, increased awareness of the sponsor’s brand might be directed to potential consumers and be achieved by viewing or attending a sponsored event (e.g., Quester and Farrelly 1998). Alternatively, the objective of increased sales might be directed to other participating sponsors and might be achieved through hospitality at the sponsored event (Brown 2007) or demographic targeting through the property (e.g., in classical versus jazz music sponsorship, Oakes 2003). Research indicates that objectives vary depending on the relevant ecosystem and the size of the sponsoring entity, with small firms historically being more community oriented (Mack 1999) and larger firms more branding focused (Söderman and Dolles 2010) and media oriented, though often with specific objectives poorly defined (Papadimitriou et al. 2008). Objectives and objective setting are not standalone research topics but rather are integrated in consumer studies of sponsorship effectiveness. Objectives include strategic outcomes such as market share, return on investment (ROI), and return on objectives (ROO) but may also include return on purpose (ROP), particularly for programs integrating CSR.

Engagement

In Fig. 1, the Engagement column represents what partners will do in this relationship and includes the contract, because any activity may be part of the contract or instead part of leverage by the sponsor. The term “leverage” describes all sponsorship-linked marketing communications and activities collateral to the sponsorship investment, while “activation” refers only to communications and activities in which the potential exists for audiences to interact or in some way become involved with the sponsor (Weeks et al. 2008; although O’Reilly and Horning (2013) refer generally to “activation”). In short, leverage is the total amount of spending beyond the sponsorship contract, and activation is a subset of this that is often on-site or online and interactive. A commonly accepted notion is that a sponsorship agreement must be leveraged to be useful to the partners, and evidence suggests that leveraging (e.g., direct-mail messages mentioning the sponsorship) can increase awareness of the relationship and, thus, product purchase (Herrmann et al. 2016).

In parallel, properties also hold objectives for sponsorships and have audience and organizational objectives for themselves. The main objective for properties in sponsorship is to secure financial support. Although properties may focus on objectives such as ticket sales, fan or patron satisfaction, attendance, or participation as their organizational goals of interest, many of their focal goals are enhanced through sponsors. Sponsor financial commitments may support the property directly, but the extent to which a sponsor activates the relationship also indirectly benefits the property.

Given the engagement potential of sport, art and cause sponsorship, brand loyalty, commitment to a brand (Mazodier and Merunka 2012), and brand attachment, the bond between the brand and the self (see Chanavat et al. 2009, Meenaghan et al. 2013), should be more common dependent variables. Further, brand passion, intense feelings about a brand (Albert et al. 2013) and brand love, emotional connections with a brand (Batra et al. 2012), could be tested. Engagement in sponsorship has been referred to as the “frequency of opportunities afforded by the property to interact with the audience” (Wakefield 2012, p. 146), whereas engagement in marketing is oriented toward building satisfying emotional bonds (Pansari and Kumar 2017) that are the basis of long-term relationships. Thus:

RQ7:

How can brand and property objectives for sponsorship engagement advance outcomes such as brand loyalty, brand attachment, brand passion, and brand love?

Engagement ecosystems

Sponsorship systems are complex. For a sports team and a museum, individual fans and members, respectively, are central audiences, but many properties are also affiliated with a beneficiary sponsee or charity such as children’s sport or art. In the partnership relationship, such audiences may be of interest for their own sake but also on behalf of the sponsor. Research considering CSR in sport sponsorship finds ambiguity in the linkages between sports properties and CSR—namely, links between sport CSR and sponsors’ own CSR or between sport CSR actions and sponsorship objectives (Djaballah et al. 2017).

Another aspect of complexity is the way sponsorship targets multiple audiences, such as athletes, volunteers, and spectators (Papadimitriou et al. 2016). Yet another aspect of complexity is the extent to which personal involvement of a high-profile individual (e.g., a company president) may influence the relationship between a sport and a business and affect firm value (Nicolau 2011). In short, much of the work to date has not captured the complexity of sponsorship relationships. Sponsorship research needs to abandon exchange theory (McCarville and Copeland 1994), with its associated orientation to selling advertising space and property assets, and adopt conceptual frames to alter the course of future research and practice. Here we consider adopting an engagement ecosystems perspective in sponsoring.

Maslowska et al. (2016) suggest that a customer engagement ecosystem encompasses brand actions, other actors, customer brand experiences, shopping and consumption behaviors, and brand dialogue. If we expand this thinking by taking their “other actors” as employees of both the sport and the brand, we can account for a great deal of what slips through the theorizing cracks in current sponsorship research. For example, employees of the sponsoring firm often work as volunteers at events and build social capital in doing so (Darcy et al. 2014). The value of considering the engagement of both consumers and employees is already firmly established in marketing (Kumar and Pansari 2016). Orienting to an engagement ecosystem moves beyond the current “sponsorship as advertising” model and even beyond the called-for relational models in sponsorship (Cousens et al. 2006). Sponsorship is a montage of relationships from sponsor employees to property employees, from audiences to participants, from media commentators to league and governmental organizations, and from third-party intermediaries to ambush marketers (influential even if unwanted).

In an effort to identify a transdisciplinary theory of engagement in organized settings, Graffigna (2017) distills literature on employee engagement, consumer engagement, and patient engagement in the health care context. This cross-disciplinary analysis resulted in five propositional arguments that are relevant here: (1) engagement is a psychological concept that differs from empowerment and activation owing to its relational nature; (2) engagement is a multicomponent, psychological experience that holds the potential for emotional, cognitive, and behavioral effects; (3) engagement is a self-transformative experience that involves deliberate decisions to modify one’s role in an organizational setting; (4) engagement develops within a relational context with another individual, task, or organization as a whole; (5) engagement is a systemic phenomenon that fosters an organizational ecosystem of engagement.

An engagement ecosystem model of sponsorship, embracing the essential tenets described, holds the potential to address challenges in sponsorship, such as the vast blocks of prime sponsor seats that go unused (Fisher 2017) or the operational incompetence of nonprofit community sports needing sponsors (Misener and Doherty 2014). An ecosystem engagement model can help sooth fans disgruntled with the commercialization of sport (Kim and Trail 2011) and dissuade the six in 10 sponsors dissatisfied with their sponsorships and seeking an early exit (IEG 2017). Thus:

RQ8:

Can partnerships investing in an engagement ecosystem model of sponsorship outperform exchange-based partnerships in terms of organizational performance and audience satisfaction?

Measurement and evaluation

Measurement of the success of a sponsorship against stated goals and objectives is a controversial topic. Survey after survey finds that managers do not measure sponsorship outcomes (e.g., Pearsall 2010). A 2018 survey by the Association of National Advertisers and the Marketing Accountability Standards Board found insufficient measurement and assessment of sponsorship, especially in terms of ROI and ROO. This section introduces current work on measurement and evaluation (see column five of Fig. 1) and then considers three moderators—congruence, commercialization and authenticity—that influence sponsorship outcomes.

Measuring consumer outcomes

Measurement of consumer-focused outcomes in sponsorship primarily follows approaches found in marketing, such as recall and recognition (Tripodi et al. 2003; Wakefield et al. 2007), attitudes (Ruth and Simonin 2003), brand image and brand equity (Cornwell et al. 2001; Grohs 2016; Wang 2017), purchase intention (Bachleda et al. 2016), and behavior (Zaharia et al. 2016). The literature is replete with measurement of outcomes, but sponsorship researchers have not forged new measures focused on sponsorship.

Measuring brand, organizational, and market outcomes

Although media outcomes are typically considered an interim measure on the path to image change or purchase, sponsoring research often treats media exposure as the ultimate outcome of interest. Considering the televised nature of sponsored events, practitioners and academics have adopted approaches that assess the value of exposure obtained in sponsoring relative to the cost of advertising exposure. The advertising value equivalency measure, borrowed from public relations, is offered by several commercial suppliers (e.g., Joyce Julius & Associates, Nielsen Sports) and is the market standard. To produce a measure of ROI, Jensen and Cobbs (2014) combine media exposure data with sponsorship pricing data from Formula 1 auto racing. Their findings suggest that, at least for Formula 1 sponsors, it is an elite subset of high-profile sponsors that gains ROI in terms of media exposure. Importantly, as the authors note, media exposure is only one metric of sponsor success and may not be the objective for some sponsors.

The most researched organizational outcome in sponsorship is brand equity, or the added value that a brand name gives to a product (Aaker 2001). Early research found that brand managers assessed sponsoring as a contributor to brand equity and, in particular, as a contributor to differentiating the brand in the marketplace and adding financial value to the brand (Cornwell et al. 2001). Subsequently, research has shown that sponsorship supports brand equity in nonprofits (Becker-Olsen and Hill 2006) and sport teams (Bauer et al. 2005). Researchers have also found that sponsors contribute to sport brand equity (Groza et al. 2012).

In contrast with the measurement of brand image in advertising, sponsorship has focused on image transfer between sponsee and sponsor (Carrillat et al. 2010; Gwinner 1997; Gwinner and Eaton 1999; Smith 2004). The image between sponsors (Carrillat et al. 2010) and that between sponsees (Chanavat et al. 2010) are also of interest. The image of goodwill is of particular importance in sponsoring (McDonald 1991). Meenaghan (2001, p. 101) argue that sponsor communications are received in a “halo of goodwill” generated by perceptions of benefit that lower an individual’s defense mechanisms (against commercial content).

Following from the discussion of engagement ecosystems, engagement behaviors are also relevant in sponsoring (Cahill and Meenaghan 2013). In keeping with Kumar and Pansari’s (2016) work, if an engagement framework were applied to sponsorship, it would need to capture engagement with the sponsorship on the part of the sponsoring brand’s employees and customers, the property’s employees and audiences, and the extent of interorganizational engagement. With engagement behaviors, defined as behavioral manifestations toward a brand or firm beyond purchase (Van Doorn et al. 2010), sponsorship might be concerned with constructs such as the proactive sharing of positive information (brand advocacy, Keller 2007), longitudinal measures of brand loyalty, goodwill, and response to sponsorship activation.

Evaluation

We found no studies that offer a systematic model for evaluating sponsorship outcomes across portfolios or rosters. As noted, the literature is replete with measures of specific outcomes but lacks organizational-level models of evaluation of ROI, ROO, or ROP. In practice, through the aforementioned advertising equivalency, brands do evaluate exposure against benchmarks of their own past exposure, the industry, and the exposure standards for the event. Brands have proprietary evaluation models that include both ROI and ROO, with data-intensive industries such as financial services being best able to address the former. In no other area is there a larger gap between academic inquiry and business need.

RQ9:

Can measurement and evaluation tools be developed in sponsorship that capture not only ROI and ROO but also engagement behaviors and ROP?

Context moderators

Several important constructs arise repeatedly in sponsorship research and influence sponsorship outcomes profoundly. While many moderators of sponsorship outcomes could be considered, the three discussed here (congruence, commercialization, and authenticity) are essential to understand as research moves forward with intensive use of sponsorship as a marketing platform. Though discussed here as moderators, these perceptions related to the context of sponsorship could also be positioned as antecedents or consequences.

Congruence

Congruence (also called “fit” (Speed and Thompson 2000) or “match-up” (McDaniel 1999)) captures how entities “go together,” share schema, or hold similarities based on “mission, products, markets, technologies, attributes, brand concepts, or any other key association” (Simmons and Becker-Olsen 2006, p. 155). The notion of fit can best be explained by categorization theory, which assumes that brands are cognitive categories formed by a network of associations organized in people’s memories (Spiggle et al. 2012). Congruence is the most frequently investigated theoretical construct in sponsorship research (Cornwell et al. 2005, Kim et al. 2015). When poorly fitting partners come together, resulting damage can occur to brand meaning clarity (Pappu and Cornwell 2014) for one and/or both partners.

Commercialization

Event commercialization refers to sponsor-initiated commercial activity surrounding special events (Lee et al. 1997). A central concern in sponsoring, particularly regarding the outcomes of cause-related sponsoring (Polonsky and Wood 2001), is the extent to which audiences perceive an event, athlete, or team as having become overly commercial. One early measure tried to capture the perception of commercialization in sport with three items (Lee et al. 1997). Subsequent works have adapted this measure (e.g., the commercialization of a sports club, Woisetschläger et al. 2014), though studies have found a negative relationship between the amount of sponsorship exposure (number of days attending a beach volleyball event) and perceptions of event commercialization on sponsor image (Grohs and Reisinger 2014).

Authenticity

Although authenticity is widely discussed in sponsorship and influencer marketing by practitioners, this construct has not gained researcher attention. Brand authenticity emerges when consumers perceive a brand as being faithful and true to itself and as supporting consumers in being true to themselves (Morhart et al. 2015). Extending this thinking to sponsoring, the relationship between a brand and a property should be perceived as faithful and true. As an example, Nike pinpointed their sponsorship of British soccer team Manchester United as strategic in building authenticity for them in Europe (Farrelly and Quester 2005). Emphasis on engagement ecosystems may partly address the challenge of authenticity. A recent discussion on the value of real consumers and employees as influencers (Conner 2018) is in keeping with such an emphasis on relevant ecosystems.

In summary, perceptions of commercialization in sponsorship relationships are associated with negative outcomes, while perceptions of congruence or fit are associated with positive outcomes. We argue, however, that congruence between sponsor and property was more important in the past, when commercialization was not as extensive in sport, arts, entertainment, or charity, than today. Furthermore, with the extensive presence of sponsoring as a marketing activity, most consumers can now imagine why a bank might sponsor a running event. That a sponsorship holds a “logical connection” and “makes sense” are two items from the popular five-item fit scale (Speed and Thompson 2000). The evolved question of relevance today is thus:

RQ10:

Given extensive commercialization and expansion of sponsorship as a marketing platform, is relationship authenticity now a better predictor of positive sponsorship outcomes for the sponsor and sponsee than relationship congruence?

Subsequent decisions

Sponsorship contracts have end dates but are oftentimes renewed, and this topic brings us to the final column of Fig. 1. Research in cultural sponsorship indicates that relationships can fade and become vulnerable to triggers that can lead to and even hasten termination (Olkkonen and Tuominen 2008). Still, scant research addresses renewals, contract breaches, or termination of sponsorship contracts. Decision making at the end of a contract is important in two ways. First, renewal or termination is a business decision having a meaningful impact on the contractual parties. Second, sponsorship renewal or termination holds important consequences for the partnership’s audiences and for any other organizations that will partner in the future, as past partnerships influence new partnerships. Given the importance of the trajectory of sponsorship decision making represented in renewal, nonrenewal/termination and new partner development, Table A2 in the Web Appendix reviews the articles dealing with subsequent sponsorship decisions. In this section the three possible outcomes at the end of a contract—renewal, termination and new partner development—are examined with emphasis on ecosystem dynamism.

Renewal

Similar to many other business relationships, sponsorships are longer lasting when based on trust and commitment (Farrelly and Quester 2003b). Although long-term sponsorships are associated with positive outcomes for sponsors, studies on sponsorship renewal announcements and stock market response are equivocal, with some showing a negative impact on stock price (Clark et al. 2009; Deitz et al. 2013) or renewal as a nonevent (Kruger et al. 2014; Mazodier and Rezaee 2013). Regardless, research finds that long-term sponsorship relationships deliver market values over time. For example, in a multi-country study of 25,000 individuals over a four-year period, Walraven et al. (2014) show that recall levels increased over time for the sponsor relationship. Long-term relationships based on several renewals may even afford organizations an inimitable strategic resource (Jensen et al. 2016).

Nonrenewal/termination

Farrelly (2010) examines relationship-related reasons for sponsorship relationship termination. Through interviews with sport properties and sponsors, he finds that changing perceptions of value, opportunity, and responsibility typically contribute to relationship failure. Ending a sponsorship reduces financial support for the property and discontinues a sponsor’s marketing communication program; however, it can also come with managerial (Ryan and Blois 2010) and fan upset (Delia 2017) that can be costly to partners. Sponsorships in the context of global partnerships, such as the Olympics, often end because of unfavorable economic conditions but also “clutter” from additional sponsors that dilute the effect of sponsoring for any one sponsor in the event roster (Jensen and Cornwell 2017).

Ending a sponsorship relationship does not mean the ending of sponsorship effects. Across four sponsorship relationships, McAlister et al. (2012) find that six months after the event, 20% of respondents recalled the new sponsor while 42% recalled the old sponsor, depending on the number of years the old sponsor had been in place and the number of years since the new sponsor began. Analogous to how an advertising campaign has carryover recall after a campaign ends, sponsorships can hold residual recall in the minds of consumers for many years (Edeling et al. 2017). As discussed, one organizational outcome of sponsorship is brand equity for both the sponsor and sponsee. Residual recall and recognition (and other aspects of brand awareness and image) after termination of a sponsorship relationship can be termed “residual equity.” Theoretically, residual equity should be highest with extended time together in a partnership and extensive investment in communicating the partnership, while it should dissipate over time with the absence of an active relationship. Thus:

RQ11:

Does a longer partnership, when accompanied by shared investment in communicating the link between the sponsor and the property, result in greater sponsor and property equity at termination and extended duration of residual equity?

New partner searching

While new partner searching goes back to the start of the process outlined in Fig. 1, this reiteration comes with some important but unexamined aspects of sponsoring. Sponsorships as a communication platform differs from advertising in that the uptake of a previously held sponsorship by another brand means that initially the new sponsor’s communications may not be as effective, as residual recall of the previous sponsor will occur (Edeling et al. 2017). This potential interference and possible confusion could be even more problematic for brands taking over from a direct competitor in the same industry. Thus:

RQ12:

Do properties taken over from a direct competitor in the same industry face higher levels of incorrect recall for a longer time than properties taken over from a noncompeting brand, and does the level of communication for the new partnership moderate this effect?

In examining renewals, terminations, and new partner searching, we argue that future research should advance a network approach. Sponsoring engages a multiplexity of relationships in which actors belong to local, regional, national, or international ecosystems. Social networks in sponsorship have one important characteristic that must be considered—they are fast-evolving sequential networks; that is, sponsor portfolios and property rosters are constantly changing. Marketing research offers precedence where sequential networks are considered (e.g., Ansari et al. 2011), but this approach has not been applied to sponsorship.

External and unpredictable events

Also influencing the sponsorship process are categories of external and unpredictable events (see bottom of Fig. 1). We cannot examine all possible external events but discuss some of the most common ones here, including rivalry, winning, ambushing, scandal, and controversy. In this section emphasis is placed on how negative events might be mitigated.

Rivalry

Rivalries, in which teams, athletes, or fans feel intense competition against one another, are predictable, even persistent. Rivalries can be exclusive or multifaceted and varied in intensity level and the extent to which they are bidirectional (as strong for one team as the other) (Tyler and Cobbs 2017). Importantly, the nature of rivalry in sport can extend to strongly held likes and dislikes of sponsoring brands. Research on rival teams finds that fans of a team show negative brand attitudes toward the rival team’s beer sponsor (Bergkvist 2012). Rivalry at the national level is also important to sponsorship perceptions. Increasing animosity and ethnocentrism toward a country participating in sport by fans of another country negatively affects impressions of the sponsoring brand (Lee and Mazodier 2015).

While rivalries can be good for sport audiences (with fans keen to see rivals play) and a stimulus to growth when competition supports competitive spectacle, rivalry is also associated with negative images of aggression. Work considering how sponsorship communication strategies might attenuate negative sponsorship effects of rivalry find some influence, with fans having low team identification, though less so for those highly identified (Grohs et al. 2015). Theoretically, rivalries extend from social identity and group categorization and, according to Grohs et al. (2015), might be addressed by research that considers how sponsorship messaging frames identity. Thus:

RQ13:

Do sponsorship leverage and activation that establish supra-categories of identification to which rivals belong (e.g., interest in the game of basketball to which teams belong) mitigate the negative effects of sport rivalry?

Winning

Although winning any particular event, be it a dance contest or the Olympics, is unpredictable, the trends leading up to the event attract and influence sponsorship investment. An event study of stock price shifts related to winning the Indianapolis 500 auto race finds that it is the unexpected new winner that influences prices (Cornwell et al. 2001). Sponsoring a winning team is also associated with increased intent to purchase sponsors’ products, especially among casual fans (Ngan et al. 2011). That being said, research still knows little about how holding a winning profile or being an ultimate winner of an event relates to sponsor and sponsee outcomes. Evidence suggests that continual support of a team or program that is not a winner is due to individual identification with the larger domain of interest (Fisher and Wakefield 1998). Thus, similar to the discussion of rivalry, orienting to the supra-category may be helpful to teams and their sponsors when they do not have a winning profile.

RQ14:

Does moving sponsorship audience interest (through leveraging or activation) to a conceptual domain above the team/participant level mitigate negative outcomes (e.g., not winning) for properties and sponsors?

Ambushing

Early discussions conceived of ambush marketing as a deliberate attempt to mislead audiences regarding the true sponsor of an event (Payne 1998). Works discussed ambushing as an unethical practice (O’Sullivan and Murphy 1998) but, at the same time, viewed it as an imaginative marketing practice (Meenaghan 1994). Evolved thinking treats ambush marketing as a way to gain awareness, attention, or the goodwill generated by being associated with a property, without having an official sponsorship relationship (Burton and Chadwick 2018). Indeed, research indicates that sponsorship contracts create groups that are allowed to associate with a newsworthy event and groups that are not allowed to associate where no distinction had existed previously (Cornwell 2014, also see Scassa 2011 on legislation).

As noted, defining ambushing has been of research interest, as has policing and countering ambushing (McKelvey and Grady 2008; Townley et al. 1998). Other work has focused on examining the extent of the ambushing threat (Chanavat and Desbordes 2014, Carrillat et al. 2014) and imagining ways to enhance the legitimacy of a sponsorship relationship through a measured response to ambushing (Farrelly et al. 2005). Largely uninvestigated to date are the characteristics of the ambusher as influential in ambushing response (see Dickson et al. 2015 for an exception). In marketing, Paharia et al. (2010) find that some people react positively to underdog brand biographies and relate to them personally. Applied to sponsorship, an underdog brand (when facing a dominant sponsor) might be positively received as an ambusher.

Research also finds that consumers are generally indifferent to ambush marketing and do not distinguish between official and pseudo sponsors (Séguin et al. 2005). When aware that a firm is an ambusher, however, consumers tend to perceive the ambush as unethical (Dickson et al. 2015). Empirical evidence shows that ambushing marketing disclosure decreases favorable attitudes toward the ambushing brand (Mazodier et al. 2012). Ambushing is also negatively associated with the value of sponsorship partnerships (Séguin et al. 2005). Nonetheless, when people are not aware of an ambushing attempt, increased recognition of the ambusher as a sponsor occurs (Pitt et al. 2010).

In terms of a counter-ambushing strategy, previous findings suggest that decrying ambushing often results in cementing a relationship between the ambusher and the property in the minds of consumers (Humphreys et al. 2010). Because the specifics of who played what role may be lost over time, research suggests it is best to emphasize the link between the true sponsor and the property (Portlock and Rose 2009; Wakefield et al. 2007; Wolfsteiner et al. 2015) rather than bring attention to the ambusher. Importantly, as mentioned, Kim et al. (2015) do not include ambushing as a factor in their meta-analysis. Our review identified 33 empirical ambushing studies (see Table A3 in the Web Appendix), and thus including ambushing in a meta-analysis may soon be possible. Any future research should consider the long-term effects of ambushing. Thus:

RQ15:

Do ambushing effects that initially increase the false recognition of the ambusher as a true sponsor increase over time, and are they moderated by counter-ambushing communications?

Scandal

A scandal in an event or by an influencer can dramatically affect marketing-related outcomes of sponsorship. Negative news can cause sponsors to leave an ongoing relationship, and when the news is about a sponsor, such as when the Houston Astros had to deal with the Enron crisis (Jensen and Butler 2007), it can result in the property distancing its brand from a relationship. In this area, research has focused more on individual celebrity endorsers (e.g., Carrillat and d’Astous 2014; Knittel and Stango 2013; Louie et al. 2001; Um and Kim 2016; Yoon and Shin 2017) than on sponsorship relationships with teams or large-scale events, even though these topics can command media attention. An exception is the work of Kulczycki and Königstorfer (2016), which shows how corruption of a governing body for sport mega-events such as the Olympics or FIFA World Cup can negatively influence attitudes toward any event associated with that governing body and toward sponsors.

Controversy

Another significant external influence on the sponsorship process and outcomes is controversy. Social activism surrounding sponsorship by products such as tobacco (e.g., Ayo-Yusuf et al. 2016), alcohol (e.g., Cody and Jackson 2016), unhealthful food/drink (e.g., Macniven et al. 2015), and gambling (Hing et al. 2013, Lamont et al. 2011) can, if followed by legislation, change the field of sponsorship. For example, early tobacco sponsorship was effective at reaching markets (e.g., Rosenberg and Siegel 2001) but was banned in most countries as social awareness of the negative health implications of smoking disseminated. This topic has received extensive research interest in recent years. To support integration and future research, Table A4 in the Web Appendix summarizes conceptual and empirical work on controversial products.

A host of additional external variables could also cause a crisis. Scandals and controversies can be short-lived or never-ending, broad-based as in the case of certain products (e.g., alcohol), or narrow as in sponsorship investments from oil industry companies in art galleries and community events. All these represent a risk from the perspective of sponsor and sponsee but also represent an ecosystem in which social advocacy is played out and writ large. Engagement in social issues, though of a different type than is sought by most sponsors, is part of the ecosystem. The current mode of social engagement, in which sponsors and properties are criticized for investments that align them with issues, people, organizations, and behaviors considered negatively by part of society, has come to vest both sponsors and properties with a new responsibility in social issues. Research is necessary to better understand these new roles.

RQ16:

In advance of, and during sponsorship scandal and controversy, what risk reducing behaviors can sponsors and properties employ and still be respectful to ecosystem members?

In summary, sponsorship research and practice have reached a point at which legacy thinking of sponsorship as advertising no longer matches with the strategic employment of sponsorship as a marketing platform. Contextual changes in communications, social activism, and perceptions of commercialization have brought sponsoring to a turning point. The sponsoring process model is offered as a first step in turning the tide of research investment toward marketing management.

Managerial insights

To support management decision making in this space, Table 2 summarizes findings for managers and highlights insights into the sponsoring process discussed previously. The table details the process aspects from Fig. 1 and then describes the process characteristics and related managerial considerations. Table 2 was vetted for relevance by four industry experts. The goal was to learn if the process and insights accorded with their experience. One response stated, “The table represents quite a comprehensive view of the aspects of the sponsorship process that should be considered.”