Abstract

Whereas past research has focused on negative outcomes that can transfer from one firm to another, this paper examines conditions under which a service failure by one firm creates an opportunity to enhance customer evaluations of a different firm in a contiguous service experience. Thus, a new external service recovery phenomenon is demonstrated in which consumers have more favorable perceptions of a firm when there was a previous failure with a different firm compared with no previous service failure. Study 1 tests hypotheses related to consumers’ perceptions of a hotel’s external service recovery after an airline’s service failure. Study 2 examines an external recovery effort in the hotel industry that follows a service failure from an unrelated hotel, an affiliated hotel, and the same hotel. Study 3 utilizes a laboratory experiment to assess the effects of external recovery in a restaurant setting. Results from all three studies suggest external recovery leads to appreciable gains for the recovering firm but only when it is not affiliated with the failing firm. Implications for service managers suggest several simple and relatively low cost tactics can be implemented to capitalize on other firms’ failures. In particular, this research highlights strategies that encourage frontline employees to listen to customers and, if a prior failure is detected, make simple gestures of goodwill.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Imagine a customer who just experienced a service failure with a retailer arriving at a second retailer. Is the customer more likely to be dissatisfied with the second retailer because of the preceding bad experience with the first retailer? Or does the preceding service failure provide an opportunity to create a more satisfied and loyal patron? The basis for the scenario described here is quite common, as consumers frequently engage with a variety of service providers throughout a given day. For instance, consider the number of firms with which a consumer interacts while engaging in routine travel: airlines, restaurants, hotels, rental car companies, taxi cabs, and tour guides. Even during a routine trip to the mall, the average consumer visits more than just a single retailer (Soriano 2006). Although participation in contiguous service encounters may benefit consumers via efficiency gains and other advantages, given that service products are known to have high failure (Maxham and Netemeyer 2002; Voorhees et al. 2006) and low recovery rates (McGregor 2008), a negative outcome is likely for at least one service encounter in the sequence. Thus, it is important to understand how a service failure at one organization provides a recovery opportunity for a firm involved in a subsequent service encounter with the same customer.

Past research suggests several ways in which perceptions of one service encounter can “spill over” to a subsequent encounter. Service spillover refers to the impact of a service encounter with one organization on a subsequent encounter with a different organization. For instance, consumer evaluations of a service provider have been shown to spill over onto a partner firm in an alliance context (Bourdeau et al. 2007). Thus, a negative encounter with one firm can lead to negative perceptions of a subsequent encounter. More generally, several studies show the existence of mood effects in service encounters (e.g., Gardner 1985; Menon and Dube 2000), such that a consumer’s negative mood could plausibly carry over to a subsequent encounter with a different firm, resulting in poor evaluations of both firms.

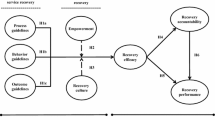

In contrast to prevailing thought, and drawing from research on contrast effects and equity theory, we conduct three independent studies to demonstrate conditions under which one firm can gain from the misfortune of other firms. Specifically, we introduce and investigate the implications of external service recovery, whereby a firm responds to a customer who experienced a prior failure with another firm within a contiguous series of services by providing them with a goodwill gesture. In these situations, we demonstrate that recovering firms reap substantial benefits and achieve more positive outcomes after a service failure with another, unrelated firm than if no preceding failure occurred.

The benefits of external recovery are shown via a series of three independent studies. Study 1 replicates the negative spillover effect identified in prior research and shows that an external recovery enacted by a second firm counteracts spillover to the point where positive outcomes are achieved. Study 2 identifies firm affiliation as an important boundary condition to the external recovery benefits identified in Study 1 and supports equity and disconfirmation as two important mediating mechanisms. Study 3 employs a mock restaurant laboratory setting to replicate the previous results while addressing some of the limitations of Studies 1 and 2.

Research background

Overview of service failure, recovery, and the paradox

The objectives of relational marketing strategies focus on high customer retention rates, which depend on superior service delivery (Berry 1995). Unfortunately, the unique characteristics of services often make error-free service an unrealistic goal (Fisk et al. 1993). Problems and complaints are simply bound to occur at some point over the course of a customer’s relationship with a firm. Service failures are thought to decrease consumers’ trust and commitment to an organization (Bejou and Palmer 1998), subsequently decreasing loyalty and increasing switching behavior. Thus, a firm’s ability to minimize service failures and successfully recover from failures that occur is crucial for customer retention and, hence, long-term revenue maximization.

Although researchers and practitioners are aware of the importance of service recovery strategies (Reichheld and Sasser 1990), many service failures go unresolved or, if a recovery strategy is enacted, the firm’s solution often fails to appease the consumer (Tax and Brown 1998). A study involving 600 U.S. companies states that over 55 % of respondents believe organizations are inefficient and ineffective at fixing their problems (Gross et al. 2007). This recovery problem is compounded by the fact that firms are often unaware failures occur, because unhappy customers may fail to complain (Stephens and Gwinner 1998; Voorhees et al. 2006). Among the most consequential outcomes of such unresolved failures is a negative impact on customer retention (Keaveney 1995), which in turn leads to lost customer lifetime value (Rust et al. 2000). Moreover, the risk of damaging customer lifetime value through poor recovery is increasing as average customer service scores have been declining over the last several years (ACSI 2010; McGregor 2008).

Interestingly, firms that enact an especially effective service recovery strategy are thought to achieve a paradoxical, positive outcome. The service recovery paradox posits that customers with satisfactorily remedied service failures can be more satisfied, loyal, and likely to engage in positive word of mouth than customers who did not experience a service failure (Hart et al. 1990; Smith and Bolton 1998). (Bitner et al. 1990) present evidence to support this phenomenon, as their research finds nearly 24 % of memorable, satisfactory encounters result from a successful service recovery after a service failure. Thus, if an organization recognizes the failure, and if a successful recovery effort is made, positive customer outcomes may result. The concept of the service recovery paradox is especially important to managers because it validates recovery efforts and presents the possibility that service failures do not always ultimately result in dissatisfaction and lost customers. However, prior research is equivocal regarding the existence of the service recovery paradox (e.g., Andreassen 2001; Mattila 1999; Maxham 2001; McCollough et al. 2000; Zeithaml et al. 1996). In an attempt to resolve conflicting findings regarding the existence of the recovery paradox, (Matos et al. 2007) conducted a meta-analysis of relevant studies. Although unable to offer a definitive ruling on the existence of a recovery paradox, they find support for its existence regarding certain outcome variables, namely satisfaction.

These prior studies examine the service recovery paradox in a single-firm context. However, just as a failure and recovery are components in the overall assessment of an encounter with a single firm, they also may be included in assessments of contiguous service encounters involving two or more firms. In the latter case, the firm that initiates the recovery may benefit from enhanced perceptions resulting from the prior firm’s failure. Put differently, we argue that one firm’s service failure creates an opportunity for a different firm to capitalize on an “external recovery,” thereby resulting in more favorable outcomes for the latter firm than if no prior failure had occurred. Our attention now turns to the service spillover literature.

Spillover effects

Several authors (e.g., Bourdeau et al. 2007; Lynch et al. 1991; Simonin and Ruth 1998) consider ways in which consumer evaluations of one product influence evaluations of other products. Past research on spillover effects often is focused on cooperative marketing activities, such as brand alliances, co-branding, and joint branding. Results from this stream of research generally suggest consumers’ perceptions of one product or brand are positively related to perceptions of the partner product or brand. It follows that, as favorable perceptions of one brand tend to result in favorable perceptions for the partner brand, less favorable perceptions also may negatively affect both brands. Evidence to support such a transference of negative evaluations is provided by Simonin and Ruth (1998), who find that consumer attitudes toward a brand alliance affect impressions of each partner’s brand, although not necessarily in an equal manner.

However, there is little information on how service provider evaluations are influenced by interactions with other firms in contiguous service encounters. We argue that, unlike brand alliances and co-branding, the multi-stage processes involved in contiguous services provide opportunities for updating expectations and attitudes between encounters. As a result, adaptation theory (Helson 1971) offers insight into how consumers may react to failures in contiguous service experiences. Within this broad framework, the most recognized components analyzed in the adaptation paradigm are contrast and assimilation effects (Schwarz and Bless 1992). Contrast occurs when prior evaluations accentuate perceived differences between current and previous stimuli. For example, a grocery store may seem noisy to someone who just came from a library, whereas it may seem quiet to someone who just left a rock concert.

In the context of contiguous service encounters, the benefits of a goodwill gesture offered by a frontline employee may be accentuated if the consumer just experienced a negative encounter with a different organization. Moreover, due to this contrast effect, the resulting satisfaction may be significantly higher than if no previous failure had occurred. This effect is especially relevant to service organizations, as firms may be able to leverage other firms’ service failures to enhance consumer evaluations. Further, this phenomenon is consistent with discussions of disconfirmation of expectations in services that suggest that prior and current stimuli impact consumer expectations, which in turn influence service perceptions (Oliver 1980). More specifically, prior negative experiences reduce consumer expectations, thus creating an opportunity for greater disconfirmation when the second firm recovers.

Building on this logic, we posit that in order to capitalize on a preceding failure generated by another firm, an external recovery should be enacted. Similar to a traditional recovery, an external recovery consists of a firm’s actions in response to a prior service failure and often involves some form of recompense. For instance, in the context of a travel experience, if a hotel employee recognized that a customer just experienced a negative service experience with an airline en route to his or her destination, the employee could “externally recover” by apologizing for the customer’s misfortune and offering a simple gesture of goodwill, such as a complimentary room upgrade or a late checkout time, among other possible actions. Consistent with contrast effects and disconfirmation of expectations, we expect the customer to react more positively to these extra efforts following a service failure than if no prior failure had occurred. Thus:

-

H1:

There is an interaction between service failure and external recovery, such that consumers will have more favorable (a) satisfaction evaluations and (b) positive word of mouth intentions when there was a previous service failure with an unrelated firm compared with no previous service failure.

Study 1

The first study is designed to test H1a and H1b. Specifically, the primary research question centers on whether positive customer outcomes result from a situation in which a subsequent service provider recovers for a previous firm’s failure. We expect more positive customer perceptions for a recovering firm when preceded by a failure at a different firm than if no prior failure occurred.

Sample and data collection

The sample was drawn using a quota-controlled convenience sampling procedure in which only non-students who were at least 25 years old were included (Giebelhausen et al. 2011). Each student in an elective marketing class was asked to generate five non-student respondents as a class assignment. A self-administered online questionnaire was utilized to capture the data. Although the survey was completed by 129 respondents, one quality check item was included to detect “blind checking,” where survey respondents provide responses to items without reading or understanding them. The item read: “If you read this item, please respond ‘Disagree.” Eleven respondents provided other responses to this item, so they were removed from the dataset prior to analysis. Thus, 118 respondents remained. The sample appeared appropriately distributed across gender, ethnicity, and age. Specifically, 53 % of the sample was female. In terms of ethnic background, the sample was 78 % Caucasian, 12 % Hispanic, 4 % African-American, 2 % Asian/Pacific Islander, and 4 % “other.” The age of respondents was gathered in categories: 25–34 (19 %), 35–44 (14 %), 45–54 (41 %), and 55+ (26 %).

Procedure

The study utilized a two (service failure: present, absent) x 2 (external recovery: present, absent) between-subjects design. Respondents were randomly assigned to one of four scenarios involving an initial service encounter with an airline, followed by a subsequent service encounter with a hotel. The airline and hotel industries were selected as representative of high-contact services in which there is a high degree of customer and frontline service worker interaction (Chase 1978). Moreover, airline travel and hotel services often occur contiguously and are industries in which failure is frequent (Andreeva 1998). Service failure was manipulated by respondents experiencing a long layover and losing their seat on an oversold plane. External recovery was manipulated through an unexpected room upgrade at the hotel after telling the hotel clerk about the airline experience (see Appendix 1). After reading the scenario, subjects responded to established measures of satisfaction and word of mouth regarding the airline (see Appendix 2).

A manipulation check item revealed a significant difference in the perception of failure versus no failure, such that the airline in the failure condition was perceived as providing a worse experience compared to the airline in the no failure condition (Mfail = 2.20, Mnofail = 6.08, p < .01). Another manipulation check item revealed a significant difference in the perception of external recovery versus no recovery, such that the hotel was perceived as offsetting the previous airline experience more so in the recovery condition than in the no recovery condition (MRecovery = 3.71, MNoRecovery = 3.10, p < .05). Both manipulation checks were analyzed using the full design, with only the respective factor found to have a significant effect. Scenario realism (Dabholkar and Bagozzi 2002) was measured using a two-item, seven-point realism scale (see Appendix 2), and results indicate subjects found all four scenarios to be equally realistic (Mfail/recovery = 6.06, Mfail/no recovery = 5.81, Mno fail/recovery = 6.33, Mno fail/no recovery =5.91, p > .05) and the scenarios scored significantly above the midpoint of the realism scale (p < .05).

Satisfaction and word of mouth intentions were assessed using seven-point, Likert-type scales adapted from past research. Specifically, satisfaction was adapted from Oliver’s (1997) research (α = .96) and the word of mouth intentions scale was adapted from (Maxham and Netemeyer’s 2002) study (α = .96). Convergent and discriminant validity were evaluated—and supported—in all three studies through the method advanced by Fornell and Larcker (1981). Specifically, the average variances extracted exceeded .5 for all scales and were greater than the squared correlations between scales.

Results

The analysis method was multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA). Assumptions regarding independence, normality, and homogeneity of variance were analyzed and met.Footnote 1 Hypotheses 1a and 1b predict that consumer satisfaction and word of mouth intentions will be higher if an external recovery follows a failure by a different firm than if no initial failure occurred. Results confirm a significant main effect of external recovery (F (2,113) = 9.11, p < .01) and a marginally significant multivariate interaction between external recovery and failure (F(2,113) = 2.87, p = .06). However, the univariate interactions for satisfaction (F(1,113) = 3.08, p < .05) and word of mouth (F(1,113) = 4.18, p < .05) were both statistically significant. The data pattern is interpreted as evaluations being more favorable when another firm’s failure precedes the external recovery compared to when no failure is present. Specifically, in the “Failure/Recovery” condition, satisfaction (Mfailure/recovery = 6.57, Mno failure/recovery = 6.16) and word of mouth values (Mfailure/recovery = 6.62, Mno failure/recovery = 6.25) were higher than in the “No Failure/Recovery” condition.

Simple effects were evaluated to further probe the interaction effect. When a recovery was present, the presence of a preceding failure led to significantly higher satisfaction (F(1, 113) = 4.34, p < .05) and word of mouth intentions (F(1, 113) = 4.57, p < .05) than when no failure occurred. This pattern of results is consistent with H1a and H1b, as identical recovery actions were perceived more favorably after a failure than if there was no prior failure. The results pattern is depicted in Figure 1. Although not formally hypothesized, we also considered the difference between the recovery and no recovery groups when no failure was present. Interestingly, there were no significant differences in satisfaction or word of mouth intentions within the no failure condition. In other words, consistent with our theorizing, when no preceding failure occurred, respondents did not react more positively to a goodwill gesture by the second service provider compared to when no gesture was offered.

Discussion

Overall, the results of Study 1 support the idea that one firm’s service failure can create a rich opportunity for another firm. Specifically, higher satisfaction and word of mouth intentions resulted when a failure with a different firm preceded an external recovery, as opposed to a situation where no failure occurred. Importantly, this study supports the existence of a heretofore unrecognized external recovery phenomenon through which a firm can obtain higher satisfaction and word of mouth after a different firm’s failure than if no such failure occurred. It is important to note that the goodwill gesture (a room upgrade) in the no failure condition resulted in no significant increase in consumer evaluations. These results underscore the importance of using goodwill gestures judiciously, as our results suggest their effectiveness may be contingent on prior experiences at other service firms.

However, an important question remains as to whether a relationship or affiliation between the failing and recovering firms may attenuate or offset the external recovery benefits observed in this study of unaffiliated firms. Specifically, the results pattern observed across unaffiliated firms may change when the two firms have an established alliance or when one firm is recovering for its own failure. A second question that was not addressed in Study 1 relates to the mechanism(s) that may be driving the post-recovery outcomes. These questions are addressed in Study 2.

External recovery and firm affiliation

When a service failure occurs, a recovery may be enacted by the offending firm or a different firm that is either related or unrelated to the offending firm. We define internal recovery situations as those in which the offending firm takes steps to recover from its own failure. Unaffiliated firms are those that are unrelated and have no association with each other. For the purposes of this research, affiliated firms are those firms that are related or engage in some type of strategic alliance or partnership. Organizations operating under a parent brand, such as the Marriott or Hilton family of hotel brands, are examples of affiliated firms. In Study 2, we consider whether the pattern of results observed in Study 1 for unaffiliated firms hold in circumstances where a firm is recovering for its own transgression or for that of an affiliated firm. In addition, the question of what is driving the effect is addressed.

Regarding the mechanisms driving the external recovery effect, we posit the existence of dual mediators. In scenarios in which a firm recovers for a failure from an unrelated firm, as previously discussed, contrast theory and disconfirmation effects suggest that an external recovery enacted after the failure is more impactful than a recovery enacted if no prior failure occurred. This effect is likely a result of differences in consumer expectations for the second service encounter. Specifically, the presence of a prior failure may serve to lower expectations for a subsequent encounter, thus increasing the disconfirmation effect experienced by the recovering firm.

However, as we introduce the potential for a firm to recover from its own (internal) failure or that of an affiliated firm, we lean on additional theory bases to explain the effects. Specifically, during the evaluation of internal service failures and subsequent recovery efforts, equity evaluations often emerge as the primary mechanism due to the fact that consumers can explicitly calculate the costs and benefits associated with a service encounter—or set of encounters—with the firm (Hess et al. 2003). Based on this framework and the consistent support for equity mechanisms in internal service failure studies (e.g., Smith et al. 1999), we adopt equity theory as a second mechanism for the effects outlined in Study 2.

The constructs of equity and justice are frequently used to explain outcomes associated with service failure and recovery occurrences. For instance, these factors are known to account for over 60 % of explained variance in customer satisfaction with a failure incident and subsequent recovery effort (Smith et al. 1999). According to Oliver (1997, p. 211), equity is “a fairness, rightness, or deservingness comparison to other entities, whether real or imaginary, individual or collective, person or non-person.” The equity process is applicable to any exchange where a person invests inputs and receives outcomes (Oliver and Swan 1989). Specifically, a person is thought to compare his/her inputs and outcomes with another entity’s inputs and outcomes. This comparison leads to an equity cognition (Cook and Yamagishi 1983), in which the exchange may be deemed equitable or inequitable by the consumer.

We suggest it is plausible that different equity cognitions may result from service encounters involving affiliated versus unaffiliated firm failure/recovery situations, thus causing varying outcomes. In the case of an internal failure and recovery (i.e., when a failure and recovery occur within the same firm), a negative inequity perception will likely emerge if the firm’s recovery does not adequately compensate for its own failure, as the consumers’ perceptions of their input/outcome ratio is not equal to that of the firm’s. However, if the consumer perceives the firm’s recovery actions to be sufficient in light of the failure, the total exchange may be deemed equitable.

Comparing this internal recovery situation to one in which failure and recovery occur at different firms, equity theory suggests a consumer is more likely to perceive positive inequity with a different recovering organization. This positive inequity is the result of a positive recovery experience that is not canceled out by the firm’s own failure, as the failure was the responsibility of a different firm. In other words, we expect higher satisfaction, repatronage intentions, and word of mouth to occur due to positive inequity resulting from the separation of consumer and firm inputs and outcomes in a multi-firm context. Given that some positive equity is thought to enhance customer outcomes (Brockner and Adsit 1986), we expect the following:

-

H2:

In the context of a recovery effort, consumers will have higher levels of (a) satisfaction, (b) repatronage intentions, and (c) positive word of mouth intentions when a previous service failure is generated by another firm compared to an internal failure.

Although the current research posits that a firm can capitalize on another firm’s failure, we also consider potential differences between affiliated and unaffiliated firms. Again, in addition to the contrast and disconfirmation effects outlined in Study 1, we must consider equity theory, which contends that both affiliated and unaffiliated firms that enact a recovery after another firm’s failure should gain more than a firm that initiates a recovery for its own failure. However, considering the aforementioned co-branding and spillover literatures, it seems likely that an affiliated recovering firm may experience negative spillover resulting from the failure that would be less applicable to an unaffiliated recovering firm.

The traditional view of spillover involves a positive relationship between perceptions of the respective firms or products. For instance, a main goal of co-branding is to transfer positive associations of one brand to another. Similarly, brand extensions are meant to capitalize on the brand equity of a parent brand. In the case of service alliances, a positive relationship between consumers’ perceptions of both firms exists for both good and bad experiences (Bourdeau et al. 2007). Thus, failure/recovery situations between affiliated firms may present a unique case, in which positive consumer outcomes resulting from the recovery act may be counteracted by the spillover inherent in alliance situations. Taken together with our discussions on the roles of expectations, disconfirmation, and equity, we predict:

-

H3:

In the context of a recovery effort, consumers will have more favorable perceptions of (a) satisfaction, (b) repatronage intentions and (c) positive word of mouth intentions when there was a previous service failure with an unaffiliated firm compared with a previous service failure with an affiliated firm.

-

H4:

Equity perceptions mediate the relationship between recovering firm affiliation and (a) satisfaction, (b) repatronage intentions, and (c) positive word of mouth intentions.

-

H5:

Disconfirmation mediates the relationship between recovering firm affiliation and (a) satisfaction, (b) repatronage intentions, and (c) positive word of mouth intentions.

Study 2

Study 2 is designed to address two key research questions. First, we assess the relative effectiveness of recovery efforts made by the same firm that failed initially (internal recovery), efforts made by an affiliate of the failing firm (affiliated recovery), and those made by a firm not affiliated with the failing firm (unaffiliated recovery). Second, we assess the potential roles of equity perceptions and disconfirmation as mechanisms that mediate the effects of recovery affiliation on the outcome variables.

Sample and data collection

Study 2 utilized a two (service failure: present, absent) x 3 (recovering firm affiliation: internal, affiliated, unaffiliated) between-subjects design. Respondents were recruited from an online panel provider and directed to the online survey. In total, 264 respondents provided data suitable for analysis. Sixty-five percent of the respondents were male, and the typical age range was 25–34 years of age with 73.8 % indicating they were 25 years or older. With respect to ethnicity, 76.5 % were White/Caucasian, 7.6 % were Asian American, 7.2 % were African American, 7.2 % were Hispanic, and 1.5 % did not classify themselves in one of the preceding categories.

Respondents were randomly assigned to one of six scenarios involving service failure and recovery in a hotel. Again, the hotel industry was selected for its high degree of customer and frontline service worker interaction (Chase 1978) and the frequency of failure incidents that occur. Service failure was manipulated by respondents receiving a room without the reserved number of beds upon checking in to the hotel. Recovery affiliation was manipulated by consumers experiencing a recovery at the same hotel (i.e., internal recovery), a different hotel in the same hotel family (i.e., affiliated recovery), or an unaffiliated hotel. Recovery entailed an act of goodwill in the form of a room upgrade (see Appendix 3) and was enacted equally in all conditions.

Subjects responded to the satisfaction and word of mouth intentions scales utilized in Study 1, as well as measures for repatronage intentions, equity perceptions, and disconfirmation. Because the recovery experiences were constant across all affiliations, the variance in the disconfirmation measure should be attributed to variance in expectations entering the recovery experience. This logic is consistent with the arguments made by Boshoff (1999) regarding the role of expectations in evaluating recovery efforts. The scale for repatronage intentions was adapted from (Zeithaml et al. 1996) research, equity items were adapted from (Oliver and Swan’s 1989) study, and disconfirmation was measured using (Oliver and Bearden’s 1985) subjective disconfirmation scale. All scales were reliable with estimates ranging from .81–98.

Two manipulation check items revealed significant differences in the perception of internal, affiliated, and unaffiliated failures. First, regarding the difference between internal and external (i.e., affiliated and unaffiliated) recovery situations, the hotel utilized for the second visit was perceived as being significantly more responsible for the initial service failure in the internal condition than in the aggregated external conditions (Minternal_recovery = 5.21, Mexternal_recovery = 1.90, p < .01). Moreover, an examination of the disconfirmation and equity scores across internal and external recovery conditions provides initial support for the proposed mediating mechanisms of disconfirmation (Mexternal_recovery = 6.02, Minternal_recovery = 5.01, p < .01) and equity (Mexternal_recovery = 6.01, Minternal_recovery = 5.12, p < .01), as the results revealed that consumers experienced a larger contrast between their expectations and performance for external recoveries and these efforts were viewed as being significantly more equitable. In particular, the results for disconfirmation are consistent with expectations being lower for external recoveries than internal recoveries. Regarding the difference between affiliated and unaffiliated firms, participants perceived firms in the affiliated condition as being significantly more related than firms in the unaffiliated condition (Maffiliated = 6.03, Munaffiliated = 2.65, p < .01).

Another manipulation check item revealed a significant difference in the perception of the failure and no failure conditions, such that the hotel in the failure condition was perceived as providing a worse experience compared to the hotel in the no failure condition (Mfail = 2.26, Mno fail = 5.83, p < .01). In addition, scenario realism (Dabholkar and Bagozzi 2002) was measured, and results indicate subjects found the scenarios to be realistic (Mfail/affiliated = 5.81, Mfail/unaffiliated =5.68, Mfail/internal =5.86, Mno fail/affiliated =6.12, Mno fail/unaffiliated =6.08, Mno fail/internal =6.15) and the differences across conditions were not significant (p > .05). As in Study 1, all manipulation checks were run using the full design to determine that only the treatment of interest was significant. Manipulation check items are presented in Appendix 2.

Results

To test H2–H5, we first conducted a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) test to demonstrate the interaction between failure and recovery affiliation conditions as a baseline. After establishing the significance of the interaction, our analyses for H2 and H3 utilized planned contrasts, whereas the Preacher and Hayes (2008) process for mediation testing was used to test H4 and H5.

The MANOVA analysis contained two fixed factors (failure and recovery affiliation), and three dependent variables (satisfaction, repatronage intentions, and word of mouth intentions). As hypothesized, the results confirm a significant multivariate interaction between recovery affiliation and failure (F(10,508) = 5.56, p < .01). The pattern of results is interpreted to mean evaluations were more favorable when recovery efforts were preceded by a service failure. The interaction is also significant for the between subject tests for each dependent variable (p < .05). Moreover, follow-up simple effects analyses reveal that the dependent variables were not significantly different (p > .19) in the “No Failure” condition.

After establishing this baseline, we tested H2 and H3 using planned contrasts. Hypotheses 2a–2c predicted that satisfaction, repatronage intentions, and word of mouth intentions would be higher if a recovery follows a failure by a different firm than a failure followed by an internal recovery. In this set of planned contrasts, we compared the means of the dependent variables across the internal recovery and external recovery conditions (averaged scores for both affiliated and unaffiliated recoveries). The contrasts reveal that recovery by a different firm significantly increases consumer satisfaction (Mexternal_recovery = 6.26, Minternal_recovery = 5.78, p < .01) and word of mouth (Mexternal_recovery = 5.98, Minternal_recovery = 4.76, p < .01) compared to an internal recovery. However, the difference was not significant for repatronage intentions (Mexternal_recovery =5.39, Minternal_recovery = 5.09, p > .36). These results support H2a and H2c, suggesting that firms can experience higher satisfaction and more positive word of mouth when recovering from other firms’ failures than from their own failures.

Hypotheses 3a–3c predicted satisfaction, repatronage intentions, and word of mouth intentions are higher for unaffiliated firms initiating a recovery than for affiliated firms. Once again, we tested these hypotheses with a different set of contrasts that directly compared means across these two conditions to each other. This comparison reveals significant effects for satisfaction (Munaffiliated = 6.50, Maffiliated = 6.02, p < .01), repatronage intentions (Munaffiliated = 5.74, Maffiliated = 5.05, p < .05), and word of mouth intentions (Munaffiliated = 6.47, Maffiliated = 5.50, p < .01). Thus, consistent with H3a–H3c, unaffiliated firms obtain higher satisfaction, repatronage intentions, and word of mouth intentions after another firm’s failure than a failure by an affiliated firm (see Figure 2).

Finally, we conducted a set of follow-up contrasts to examine the extent to which external recoveries by unaffiliated and affiliated firms result in higher evaluations compared to internal recovery efforts. Results reveal that unaffiliated recoveries yield higher satisfaction (Munaffiliated = 6.50, Minternal = 5.78, p < .01), repatronage intentions (Munaffiliated = 5.74, Minternal = 5.09, p < .01), and word of mouth intentions (Munaffiliated = 6.47, Minternal = 4.70, p < .01). In contrast, comparisons between the affiliated and internal recovery conditions were significant for word of mouth intentions (Maffiliated = 5.50, Minternal = 4.70, p < .01) but not for satisfaction (Maffiliated = 6.02, Minternal = 5.78, p > .24) or repatronage intentions (Maffiliated = 5.05, Minternal = 5.09, p > .91). These post-hoc assessments suggest that the benefits of external recoveries are largely limited to unaffiliated firms, as affiliated firms only experienced an increase in word of mouth intentions compared to firms recovering for their own failures.

Hypotheses 4a–4c and H5a–5c consider whether perceived equity and disconfirmation mediate the impact of recovery affiliation on satisfaction, repatronage intentions, and WOM intentions. We tested mediating effects simultaneously for each dependent variable using Preacher and Hayes’ (2008) multiple mediation macro where the recovery affiliation condition (binary coded where unaffiliated recovery = 1 and internal and affiliated recoveries = 0) is the independent variable, equity and disconfirmation are the mediators, and each dependent variable is sequentially entered. Based on the guidance of (Zhao et al. 2010), mediation is supported with significant indirect effects (i.e., bootstrapped confidence intervals that do not overlap zero) of the independent variable on each dependent variable.

The results reveal a significant indirect effect of recovery affiliation via perceptions of equity on satisfaction (0.25; BootLLCI = 0.03, BootULCI = 0.54) and positive word of mouth (0.49; BootLLCI = 0.15, BootULCI = 0.83), but not for repatronage intentions (0.30; BootLLCI = −0.08, BootULCI = 0.79). Similarly, we found significant indirect effects via disconfirmation on satisfaction (0.24; BootLLCI = 0.07, BootULCI = 0.48) and repatronage intentions (.42; BootLLCI = −0.02, BootULCI = 0.88), but not positive word of mouth (0.31; BootLLCI = −0.01, BootULCI = 0.70). Thus, these results support dual mediation via both equity and disconfirmation for satisfaction, but for word of mouth and repatronage intentions only one of the mediators emerges as significant.

Discussion

Overall, the results of Study 2 support the general idea that one firm’s service failure can create an opportunity for an unaffiliated firm to enact an external recovery. Specifically, higher satisfaction and word of mouth intentions resulted from an external recovery that followed another firm’s failure compared to an internal failure or a failure from an affiliated firm. Moreover, results of the mediation testing suggest both disconfirmation and equity must be accounted for in order to fully capture the processes by which recovery affiliation impacts key outcome variables.

Study 3

Taken together, Studies 1 and 2 suggest that firms can benefit from other firms’ service failures, particularly when firms are unaffiliated. Study 3 seeks to replicate these results, as well as address some of the inherent weaknesses of the scenario-based designs utilized in Studies 1 and 2. Specifically, Study 3 uses a more realistic mock restaurant setting to test the research questions. To this end, we conducted a 2 (service failure: present, absent) x 2 (recovery affiliation: affiliated, unaffiliated) laboratory experiment. Respondents were randomly assigned to one of four conditions.

The use of the restaurant industry provides an opportunity to demonstrate effects beyond the hotel setting used in the first two studies. The prevalence of service failures within the restaurant industry is well-documented in prior research (see Bitner et al. 1990; Mattila 1999). Service failure was manipulated by participants experiencing a 20-minute wait at the first eatery they encountered. Recovery affiliation was manipulated by consumers experiencing a recovery by an affiliated restaurant (i.e., in the same restaurant family) or an unaffiliated restaurant. Pilot study participants (n = 100) were presented with a written description of the experimental procedure, and they responded to items assessing realism (Dabholkar and Bagozzi 2002). Results demonstrate participants found the stimuli to be realistic (Mfail/affiliated = 5.47, Mfail/unaffiliated = 5.85, Mno fail/affiliated = 6.04, Mno fail/unaffiliated = 5.40) across conditions (p > .05). The following section explains the experiment in more detail.

Sample and data collection

Participants were 137 students from an introductory marketing class. Students received course credit in exchange for their voluntary participation and were told they would be taking part in a market research study being conducted by two restaurants. Specifically, participants were told that the College of Business was approached by restaurants looking to expand to the local area. Given the College’s ongoing involvement with local businesses, this was not an unusual request. Moreover, students are accustomed to new restaurants opening in the area, as the university is located in a growing college town.

Participants were told they would be served a catered lunch from one restaurant and a dessert from a separate restaurant. In the communication with participants prior to the actual study, great care was taken to maintain a sense of professionalism and realism. Specifically, any communication was sent from the fictitious company, using a non-university email address. Also, participants were given different options for their lunch entrée and dessert, and they were asked to make their selection ahead of time. They were asked to come to the lab hungry and were told that lunch would be served promptly at the study start time.

On the day of the experiment, groups of 10–15 participants arrived at the lab and checked in with the researcher (confederate) administering the market research study. Participants were then led into a room with several tables set with plates, silverware, napkins, and glasses. Other restaurant décor (e.g., lamps and tablecloths) was used to enhance realism. The researcher described the lunch schedule, which consisted of participants being served a sandwich and chips by the first restaurant and a dessert by the second restaurant. Next, the researcher introduced the representatives (confederates) of the two restaurants. Both confederates were, at the time of the study, employed as professional servers. At this point, the first manipulation was presented wherein the confederates were introduced as representing two different restaurants (unaffiliated) or two restaurants operating under the same parent company (affiliated). The confederates were both dressed in professional wait staff attire, but they wore slightly different clothing to reinforce their association with two different restaurants. Following the introduction, the researcher announced lunch would begin. The second manipulation was presented here, as participants either were immediately served a sandwich and chips from the first restaurant (no failure), or the participants experienced a 20-minute delay (failure).

After participants completed the first portion of the dining experience, they completed a short survey on the food and service experience with the first restaurant. Next, individual participants were led into a second room one at a time, where they were greeted by the second restaurant representative. They were given the choice of a chocolate cupcake, a vanilla cupcake, or an apple. While packaging the dessert for the participant, the representative asked each participant how their lunch experience had been thus far. Participants’ responses to the question were recorded; specifically, it was noted whether each participant gave a satisfactory or less than satisfactory (e.g., complaint) response. Regardless of how the participant responded, the second restaurant representative responded by offering the person a second cookie, cupcake, or apple. Thus, all participants received a gesture of goodwill. Lastly, participants proceeded to an adjoining room where they completed a survey on their experience with the second restaurant. Upon completing the second survey, the participants were thanked for their time, debriefed, and dismissed.

Subjects responded to measures of satisfaction, repatronage intentions, and word of mouth intentions regarding the second restaurant. The scales were reliable, with construct reliability estimates ranging from .92–94. All scales and items are listed in Appendix 2. Two manipulation check items confirmed that participants perceived differences in service failure (Mno_fail = 5.60, Mfail = 3.25, p < .01) and affiliation conditions (Maffiliated = 5.78, Munaffiliated = 3.62, p < .01).

Results

As before, the analysis method was multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA). Results show a marginally significant multivariate interaction between recovery affiliation and failure (F(3,131) = 2.37, p < .08). Next, the univariate results for the significant interactions were considered. Satisfaction, (F(1,133) = 3.99, p < .05), repatronage intentions (F(1,133) = 5.32, p < .01), and word of mouth intentions (F(1,133) = 6.97, p < .05) were significant. Results support findings from Study 1, such that the occurrence of a service failure with one firm results in higher satisfaction, repatronage intentions, and word of mouth intentions with a different firm when an external recovery is enacted compared to a situation where no preceding failure occurred (see Figure 3).

To further explore this interaction, a simple effects analysis was conducted, which revealed consumers in the unaffiliated failure condition exhibited higher satisfaction (Munaffiliated_fail = 6.30, Munaffiliated_nofail = 5.83, F = 4.28, p < .05), repatronage intentions (Munaffiliated _fail 5.97, Munaffiliated_nofail = 5.35, F = 5.58, p < .05), and word of mouth intentions (Munaffiliated _fail 6.16, Munaffiliated_nofail = 5.69, F = 5.65, p < .05) compared to the no failure condition. Similar to Study 2, firms in the affiliated condition did not see significant gains in repatronge intentions (Maffiliated_fail = 5.28, Maffiliated_nofail = 5.42, p > .05), satisfaction (Maffiliated_fail = 5.68, Maffiliated_nofail = 5.97, p > .05), or word of mouth intentions (Maffiliated_fail = 5.55, Maffiliated_nofail = 5.98, p > .05) after an external recovery. Thus, Study 3 provides further support for the positive effects of external recovery documented in Studies 1 and 2, in which firms can achieve higher scores on key customer metrics after a failure at a prior firm compared to no prior failure, but this occurs only if the two firms are unaffiliated.

Follow-up analysis

Results of Study 3 provide additional support for the idea that unaffiliated firms can capitalize on another firm’s failure through the execution of an external recovery. Although not hypothesized, we also assessed the effect of verbal (dis)satisfaction expressions. More specifically, if respondents indicated they were in a state of anything other than satisfaction following the first encounter, then they likely were feeling as if their output to input ratio was out of balance and had lower expectations for service with the second provider. Thus, by classifying respondents into satisfied/not satisfied groups, we can assess if the response by the second firm restored equity evaluations or capitalized on lowered expectations.

To operationalize this analysis, participants were asked to express their feelings regarding the first encounter to the second firm’s representative, thus firmly connecting both encounters. Judges, blind to both the study’s hypotheses and conditions, subsequently coded these responses as either being satisfactory or less than satisfactory, which provided a dichotomous treatment factor for use in a follow-up MANOVA. Satisfaction, repatronage intentions, and word of mouth intentions toward the second firm were the outcome variables. Results show a significant multivariate effect of verbalized dissatisfaction (F(3, 136) = 6.60, p < .05). Univariate results confirm significantly higher repatronage intentions (Mdissatisafaction = 5.81, Mno_dissatisafaction = 5.29, p < .05) and satisfaction (Mdissatisfaction = 6.12, Mno_dissatisfaction = 5.81, p < .05), but not word of mouth intentions (Mdissatisafaction = 5.89, Mno_dissatisafaction = 5.79, p = .27), for customers who express dissatisfaction compared with those customers who do not express dissatisfaction. In other words, participants who expressed dissatisfaction with the first service encounter exhibited higher satisfaction and repatronage intentions with the second service encounter. From a practitioner perspective, assessing the effect of a preceding failure on verbally negative or neutral customers provides managerially actionable directives, as it allows for the identification of customers who would react most favorably to an external recovery gesture.

General discussion

Consumer satisfaction scores continue to decline as consumers increasingly experience a divide between service expectations and actual performance. As organizations struggle to increase retention in today’s competitive environment, they are progressively more aware of service failures and the need for successful recoveries (Reichheld and Sasser 1990). Although prior research considers the idea of spillover in the context of brand alliances (Simonin and Ruth 1998) and seamless service alliances (Bourdeau et al. 2007), we investigate spillover in a more competitive context—and with very different outcomes. Specifically, unlike the spillover literature, our studies suggest that negative spillover is interrupted or reversed by the initiation of an external recovery. That is, customers experience increased satisfaction, repatronage intentions, and word of mouth intentions when an organization initiates an external service recovery after a service failure at an unrelated firm. Interestingly, the service recoveries in all of our studies involved only simple gestures of goodwill, such as room upgrades (Studies 1 and 2) or extra food portions (Study 3).

Similar to the service recovery paradox, this research also supports the notion that satisfaction is higher after a failure than if no failure had occurred, ceteris paribus. Moreover, unaffiliated recovering firms benefitted more than affiliated recovering firms. Thus, while the current research does not directly address the traditional service recovery paradox, it does suggest a similar phenomenon exists in a multi-firm context. Further, results of our three studies indicate the external recovery phenomenon is a relatively stable effect, and it was initiated with simple gestures of goodwill.

Managerial implications

The results of this research extend our understanding of customer reactions to service recovery. In doing so, we reaffirm the importance of proper management of service failure and recovery efforts, and we offer new insights that can be leveraged for competitive advantage. Specifically, there are implications for the recruitment and training of frontline service workers, journey mapping of consumers’ service experiences, and the selection of service affiliates for contiguous service offerings. In the following section, we provide a discussion of each of these topics.

Training frontline service employees

First, this research underscores the importance of having well-trained frontline service workers. By giving service workers the authority to react to customer complaints regarding other firms, organizations can reap the rewards of increased satisfaction, repatronage intentions, and WOM intentions, among other benefits. Prior research has highlighted case studies of best-in-class service firms capitalizing on similar opportunities, such as the time a Club Med service manager rallied to develop a customized recovery in response to an external failure by an airline delivering passengers to their vacation destination (Hart et al. 1990). Building on these exemplars, service organizations should train employees to be active listeners and ask customers specific questions about their prior service encounters, particularly when they know they are part of a contiguous service experience.

While the listening strategy may appear simple on the surface, explicit training on customer listening likely will be required, as frontline employees are often consumed by the primary task at hand (e.g., serving the customer, selling a product) and therefore may not pick up on verbal or nonverbal cues that suggest less-than-ideal service from another provider. For example, when a retail employee asks a shopping mall customer, “How has your shopping experience been so far today?” the customer may respond, “Fine.” However, the customer’s body language or tone of voice may suggest otherwise. Diligent attention is particularly important regarding nonverbal communication, as it is generally accepted that nonverbal communication conveys more meaning than verbal communication (Mehrabian and Ferris 1967). Ultimately, if service employees can be trained to recognize and interpret these non-verbal cues, then they simply need to be empowered to implement an external service recovery.

Service blueprinting for contiguous services

Firms looking to train employees to leverage external recovery opportunities could benefit from a complete service blueprinting effort. Traditional service blueprinting efforts focus on an experience with a single provider (Bitner et al. 2008), yet our results suggest a broader investigation could be worthwhile. Specifically, organizations that play a role in the later stages of a contiguous process could benefit from mapping the service sequence and identifying weak spots in the service encounter series. For example, insurance providers or financial institutions could potentially leverage breakdowns in the automobile purchase process for their own benefit by listening for cues from customers and recovering appropriately.

By engaging in a blueprinting process that follows a customer through the entire purchase process, service firms can identify common failures that customers may experience with external service organizations. This knowledge would help employees probe weak points in the service chain, which would allow management teams to proactively develop recovery strategies for the most common failure situations, thus providing a more controlled and likely successful external recovery effort. Having these recovery plans is important, as the results of Study 1 support prior research on spillover effects in demonstrating that customers tend to downgrade evaluations of a service encounter due to a preceding failure episode unless an external recovery is enacted.

Selection of affiliates

Finally, the results of this research have implications for the selection of service affiliates. Many service firms, particularly in the hospitality industry, rely on formal and informal partnerships with other providers to serve their customers. Results of Studies 2 and 3 suggest that service firms must use caution when developing strategic partnerships with other service providers. More specifically, both studies demonstrate external recovery efforts fail to provide a lift in satisfaction or behavioral intentions when customers experienced a failure with an affiliate firm. As a result, partnering with service affiliates that are prone to failure may create an obligation to recover, but provide little benefit in the form of satisfaction and intentions. Ultimately, the added benefits of additional business volume through an expansive affiliate network may not be worth the added costs unless these affiliates deliver reliable service.

Theoretical implications and future research

From a theoretical standpoint, this research extends the discipline’s knowledge of spillover effects and of service failure and recovery. Specifically, our results suggest a firm may be able to capitalize on another firm’s failure through recognition of a poor experience and recovering by offering simple gestures of goodwill to compensate for a customer’s prior bad experiences. Further, our research offers insights on the process mechanisms driving the effects.

In Study 1, we build on prior work that documents how an experience with one provider carries over to another and show how this process occurs not only across transactions with a focal firm but also across interactions with multiple firms. In Study 2, we introduce and demonstrate the potential for both expectations and equity perceptions to mediate the effects of external recovery efforts. In Study 3, we bolster the results of the previous studies via a lab experiment in a more realistic restaurant setting.

Although this research provides a launching point for managers to rethink their service delivery processes and strategic partnerships and for academics to develop more complete models of contiguous service encounters, it is not without limitations that provide ample opportunities for additional research. For example, the generalizability of the results from Study 3 may be reduced due to a predominantly younger convenience sample. Future studies could extend this research to a more comprehensive representation of the consumer population. Also, these results may not be applicable across all service industries or service failures. However, other research (e.g., Collie et al. 2000) suggests the findings may apply to other services that share characteristics common to the hospitality and travel services utilized in the current study. Further, the role of customer mood and, in particular, how changes in mood that occur between positive and negative service encounters may influence recovery perceptions is a topic worthy of additional inquiry.

Whereas we consider affiliated and unaffiliated firms, future research could extend the affiliation categories. For example, there might be a difference between firms that operate under the same corporate brand versus firms that collaborate for a joint venture. Additionally, it would be interesting to assess which entity actually benefits from a firm’s goodwill gesture, as recent research suggests positive benefits may only accrue to the employee extending the goodwill and not the firm (Brady et al. 2012). It is possible these effects could be heightened in situations where the customer perceives a high level of empathy from the service employee. Likewise, it would be interesting to assess customer satisfaction levels of the first, failing firm after a second firm recovered for its failure. It may be that some of the positive goodwill derived from the second firm’s recovery circles back to perceptions of the original firm.

There are many fruitful avenues for future research with respect to the type of recovery offered. Whereas this research utilizes a complimentary room upgrade and free food as examples of external recovery manipulations, it is possible that a smaller, less costly gesture could yield similar results. Future research could assess the effects of a smaller gesture, such as a coupon, or even a simple apology. Other potential moderators may include spatial proximity between encounters, time between encounters, and magnitude of the initial service failure. For example, regarding the former, Reimer and Folkes (2009) find that spatial proximity influences the degree to which the service quality of one service provider affects consumers’ inferences of the service quality of another service provider in an alliance context via perceived managerial control. The indicated mediating effect of perceived managerial control suggests this effect also could apply to certain circumstances where competitors are located in close spatial proximity and/or are part of a larger structure or organization (e.g., a shopping mall).

Also, the magnitude of the recovery attempt (e.g., apology versus additional service) or its monetary value may moderate the effects observed in the present study. Likewise, timing of recovery may impact the effect of external service recovery efforts. For example, it would be worthwhile to determine whether timing (e.g., 2 hours or 6 hours from initial service failure) or position in the service encounter experience chain (e.g., customer interacted with 2 unaffiliated firms between the initial failure and the recovery) moderates the external service recovery effect. Similarly, frontline employee empathy may moderate the effect of external recovery on key customer outcomes. Lastly, the magnitude of service failure is known to influence consumers’ responses to recovery efforts (Mattila 2001) and may have similar effects here.

Notes

These analyses were completed in Studies 2 and 3 as well. All assumptions regarding independence, normality, and homogeneity of variance were analyzed and met.

References

ACSI. (2010). American customer satisfaction index (ACSI). Retrieved on December 30, 2011 from http:// www.theacsi.org.

Andreassen, T. W. (2001). Antecedents to satisfaction with service recovery. European Journal of Marketing, 34(1–2), 156–75.

Andreeva, N. (1998). Unsnarling Traffic Jams at U.S. airports, Business Week, August 10, 84.

Bejou, D., & Palmer, A. (1998). Service failure and loyalty: an exploratory empirical study of airline customers. Journal of Services Marketing, 12(1), 7–22.

Berry, L. (1995). Relationship marketing of services- growing interest, emerging perspectives. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 23(4), 236–245.

Bitner, M., Booms, B. H., & Tetreault, M. S. (1990). The service encounter: diagnosing favorable and unfavorable incidents. Journal of Marketing, 54, 71–84.

Bitner, M., Ostrom, A., & Morgan, F. (2008). Service blueprinting: a practical technique for service innovation. California Management Review, 50(3), 66–94.

Boshoff, C. (1999). RECOVSAT: an instrument to measure satisfaction with transaction-specific service recovery. Journal of Service Research, 1(3), 236–249.

Bourdeau, B., Cronin, J. J., & Voorhees, C. M. (2007). Modeling service alliances: an exploratory investigation of spillover effects in service partnerships. Strategic Management Journal, 28, 609–622.

Brady, M. K., Voorhees, C. M., & Brusco, M. J. (2012). Service sweethearting: its antecedents and customer consequences. Journal of Marketing, 76(2), 81–98.

Brockner, J., & Adsit, L. (1986). The moderating impact of sex on the equity-satisfaction relationship: a field study. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(November), 585–590.

Chase, R. B. (1978). Where does the customer fit in a service operation? Harvard Business Review, 56, 137–42.

Collie, T. A., Sparks, B., & Bradley, G. (2000). Investing in interactional justice: a study of the fair process effect within a hospitality failure context. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, 24(4), 448–472.

Cook, K. S., & Yamagishi, T. (1983). Social Determinants of Equity Judgments: The Problem of Multidimensional Input. In D. M. Messick & K. S. Cook (Eds.), Equity Theory: Psychological and Sociological Perspectives (pp. 95–126). New York: Praeger.

Dabholkar, P. A., & Bagozzi, R. P. (2002). An attitudinal model of technology-based self-service: moderating effects of consumer traits and situational factors. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science , 30(3), 184–201.

Fisk, R. P., Brown, S. W., & Bitner, M. (1993). Tracking the evolution of the services marketing literature. Journal of Retailing, 69(1), 61–103.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement errors. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 39–50.

Gardner, P. M. (1985). Mood states and consumer behavior: a critical review. Journal of Consumer Research, 12, 281–300.

Giebelhausen, M. D., Robinson, S. G., & Cronin, J. J., Jr. (2011). Worth waiting for: increasing satisfaction by making consumers wait. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(6), 889–905.

Gross, G., Caruso, B., & Conlin, R. (2007). A Look in the Mirror: The VOC Scorecard. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Hart, C., Heskett, J. L., & Sasser, W. E. (1990). The profitable art of service recovery. Harvard Business Review, 68(4), 148–156.

Helson, H. (1971). Adaptation-Level Theory. New York: Harper.

Hess, R. L., Ganesan, S., & Klein, N. (2003). Service failure and recovery: the impact of relationship factors on customer satisfaction. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 31(2), 127–145.

Keaveney, S. M. (1995). Customer switching behavior in service industries: an exploratory study. Journal of Marketing, 59(2), 65–83.

Lynch, J. G., Jr., Chakravarti, D., & Mitra, A. (1991). Contrast effects in consumer judgments: changes in mental representations or in the anchoring of rating scales? Journal of Consumer Research, 18(3), 284–298.

Matos, C. A., Henrique, J. L., & Vargas Rossi, C. A. (2007). Service recovery paradox: a meta-analysis. Journal of Service Research, 10(1), 60–77.

Mattila, A. S. (1999). An examination of factors affecting service recovery in a restaurant setting. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, 23(3), 284–298.

Mattila, A.S. (2001). The effectiveness of service recovery in a multi-industry setting. Journal of Services Marketing, 15(7), 583–596.

Maxham, J. G., III. (2001). Service Recovery’s influence on consumer satisfaction, positive word-of-mouth, and purchase intentions. Journal of Business Research, 54(1), 11–24.

Maxham, J. G., III, & Netemeyer, R. G. (2002). A longitudinal examination of complaining customers’ evaluations of multiple service failures and recovery efforts. Journal of Marketing, 66(4), 57–71.

McCollough, M. A., Berry, L. L., & Yadav, M. S. (2000). An empirical investigation of customer satisfaction after service failure and recovery. Journal of Service Research, 3(2), 121–137.

McGregor, J. (2008). Customer backlash against bad service. Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved on October 20, 2011 from http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/23283402

Mehrabian, A., & Ferris, S. R. (1967). Inference of attitudes from nonverbal communication in Two channels. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 31(3), 248–252.

Menon, K., & Dube, L. (2000). Ensuring greater satisfaction by engineering salesperson response to customer emotions. Journal of Retailing, 76(3), 285–307.

Oliver, R. L. (1980). A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. Journal of Marketing Research, 17(4), 460–469.

Oliver, R. L. (1997). Satisfaction: A Behavioral Perspective on the Consumer. McGraw-Hill, New York, NY.

Oliver, R. L., & Bearden, W. O. (1985). Disconfirmation processes and consumer evaluations in product usage. Journal of Business Research, 13(3), 235–246.

Oliver, R. L., & Swan, J. E. (1989). Equity and disconfirmation perceptions as influences on merchant and product satisfaction. Journal of Consumer Research, 16(December), 372–383.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891.

Reichheld, F. F., & Sasser, W. E. (1990). Zero defections: quality comes to services. Harvard Business Review, 68, 105–111.

Reimer, A., & Folkes, V. (2009). Consumers inferences about quality across diverse service providers. Psychology and Marketing, 26(12), 1066–1078.

Rust, R. T., Zeithaml, V. A., & Lemon, K. N. (2000). Driving Customer Equity. How Customer Lifetime Value is Reshaping Corporate Strategy. New York, NY: The Free Press.

Schwarz, N., & Bless, H. (1992). Assimilation and Contrast Effects in Attitude Measurement: An Inclusion/Exclusion Model. In J. F. Sherry Jr. & B. Sternthal (Eds.), Advances in Consumer Research (Vol. 19, pp. 72–77). Provo: Association for Consumer Research.

Simonin, B. L., & Ruth, J. A. (1998). Is a company known by the company it keeps? assessing the spillover effects of brand alliances on consumer brand attitudes. Journal of Marketing Research, 35(1), 30–42.

Smith, A. K., & Bolton, R. N. (1998). An experimental investigation of service failure and recovery: paradox or peril? Journal of Service Research, 1(1), 65–81.

Wagner, J. (1999). A model of customer satisfaction with service encounters involving failure and recovery. Journal of Marketing Research, 36, 356–72.

Soriano, V. (2006). Converting browsers into spenders, research review. International Council of Shopping Centers, 13(2), 9–13.

Stephens, N., & Gwinner, P. (1998). Why don’t some people complain? a cognitive-emotive process model of consumer complaint behavior. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 26(3), 172–189.

Tax, S. S., & Brown, S. W. (1998). Recovering and learning from service failure. Sloan Management Review, 40, 75–88.

Voorhees, C. M., Brady, M. K., & Horowitz, D. M. (2006). A voice from the silent masses: an exploratory and comparative analysis of Noncomplainers. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 34(4), 514–527.

Zeithaml, V. A., Berry, L. L., & Parasuraman, A. (1996). The behavioral consequences of service quality. Journal of Marketing, 60(April), 31–46.

Zhao, X., Lynch, J. G., & Chen, Q. (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(2), 197–206.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Study 1 scenario manipulation summaries

Base scenario

Imagine that you and two of your close friends are on a much-anticipated winter break trip. On the day of the trip, you arrive at the airport, check into your flight, and board the plane.

Failure manipulation

(No failure) After one layover (plane change), you arrive at your final destination. After getting your bags, you take a taxi to your hotel. Upon arrival at your hotel and while checking in, you strike up a conversation with the hotel desk clerk.

(Failure) While in-between flights (you had one layover/plane change) the airline gate agent informs you that the flight was oversold and that you and your friends are being bumped, and you will not have seats on the flight as scheduled. She informs you that you will be booked on a later flight. As a result, you experience a 6 hour delay. Upon arrival at your hotel and while checking in, you strike up a conversation with the hotel desk clerk and complain to the clerk about your airline service issue and unfortunate 6 hour delay.

Recovery manipulation

(No recovery) The desk clerk completes the check-in process and gives you the keys to the room that you reserved.

(Recovery) The desk clerk completes the check-in process and, to your surprise, gives you the keys to an upgraded room: a 2-bedroom Jr. suite with a premium view.

Appendix 2: Scale items

All items were measured on 7-point, Likert scales anchored by strongly disagree/strongly agree unless otherwise noted.

Satisfaction (adapted from Oliver 1997)

-

I am satisfied with this hotel/restaurant.

-

I think that I did the right thing when I selected this hotel/restaurant.

-

I am happy with this hotel/restaurant.

Positive Word of Mouth Intentions (adapted from Maxham and Netemeyer 2002)

-

I would likely say positive things about this hotel/restaurant.

-

I would recommend this hotel/restaurant to my friends.

-

If my friends were looking for a hotel/restaurant, I would tell them to try this one.

Repatronage Intentions (adapted from Zeithaml et al. 1996)

-

I would stay/eat at this hotel/restaurant again.

-

I would stay/eat at this hotel/restaurant more often.

Equity (adapted from Oliver and Swan 1989)

-

The treatment given to me by the hotel was:

-

Unfair to me/Fair to me

-

Less than I deserved/More than I deserved

-

Unequitable to me/Equitable to me

-

Disconfirmation (measured on a 7-point bipolar scale, adapted from Oliver and Bearden 1985)

-

Overall, my experience with the hotel was:

-

Much worse than expected/ much better than expected

-

Much poorer than I thought/ much better than I thought

-

An unpleasant surprise/ a pleasant surprise

-

Fell short of expectations/ exceeded expectations

-

More problematic than expected/ less problematic than expected

-

Realism (adapted from Dabholkar and Bagozzi 2002)

-

The situation described was realistic

-

I had no difficulty imagining myself in the situation

Manipulation Checks

-

Study 1

-

I had a bad experience with the airline.

-

The hotel compensated me for my previous airline experience.

-

-

Study 2

-

I had a bad experience with the hotel.

-

To what extent are the two hotels/restaurants related or affiliated with each other? (Not related at all/Strongly related)

-

To what extent is the second hotel responsible for the service failure at the first hotel? (Not responsible at all/Completely responsible)

-

-

Study 3

-

I had a bad experience with the restaurant.

-

The restaurant compensated me for my previous restaurant experience.

-

Appendix 3: Study 2 scenario manipulation summaries

Baseline Scenario

Imagine that you and two of your closest friends are headed to the beach for a weekend getaway. You made plans several weeks in advance and everyone is very excited about the trip. Finally, the weekend arrives and you head to the beach. You arrive at the Seabreeze Hotel, a Coastal Hotel Group property, and go to the front desk to check in.

Failure manipulation

(No failure) When you get to the desk, the hotel clerk gives you key cards to a room with two queen beds (exactly what you booked).

(Failure) When you get to the desk, the hotel clerk informs you that your reservation has been lost. After waiting 10 minutes, you are given key cards to a room with one king bed (although you booked a room with two queen beds). There are no other rooms available, so you and your friends take the room with one king bed (hopefully, you′re not the one sleeping on the sofa).

Three months later, you and your friends decide to go back to the beach.

Recovery affiliation manipulation

(Internal) You make reservations at the same hotel, the Seabreeze (again, for a double queen room). As you check in, you talk about your last experience when you stayed at this hotel and ask if a room with two queen beds is available. After you explained your prior experience, the front desk clerk tells you that not only do they have a queen room reserved for you, but he is going to move you to a queen suite at no additional charge. The queen suite is larger than a regular room it has a separate living room, two bathrooms and two queen beds. The queen suite is larger than a regular room it has a separate living room, two bathrooms and two queen beds.

(Affiliated) You make reservations at a different hotel, The Oceanside Hotel (again, for a double queen room). This hotel is affiliated with the same hotel group as the first hotel you stayed at, the Coastal Hotel Group. As you check in, you talk about your last experience when you stayed at another hotel owned by the same Hotel Group (The Seabreeze) and ask if a room with two queen beds is available. After you explained your prior experience, the front desk clerk tells you that not only do they have a queen room reserved for you, but he is going to move you to a queen suite at no additional charge. The queen suite is larger than a regular room – it has a separate living room, two bathrooms and two queen beds.

(Non-affiliated) You make reservations at a different hotel, The Oceanside Hotel (again, for a double queen room). As you check in, you talk about your last experience when you stayed at a competitive hotel (The Seabreeze) and ask if a room with two queen beds is available. After you explained your prior experience, the front desk clerk tells you that not only do they have a queen room reserved for you, but he is going to move you to a queen suite at no additional charge. The queen suite is larger than a regular room – it has a separate living room, two bathrooms and two queen beds.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Allen, A.M., Brady, M.K., Robinson, S.G. et al. One firm’s loss is another’s gain: capitalizing on other firms’ service failures. J. of the Acad. Mark. Sci. 43, 648–662 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0413-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0413-6