Abstract

Detecting delirium in elderly emergency patients is critical to their outcome. The Nursing Delirium Screening Scale (Nu-DESC) is a short, feasible instrument that allows nurses to systematically screen for delirium. This is the first study to validate the Nu-DESC in a German emergency department (ED). The Nu-DESC was implemented in a high-volume, interdisciplinary German ED. A consecutively recruited sample of medical patients aged ≥ 70 years was screened by assigned nurses who performed the Nu-DESC as part of their daily work routine. The results were compared to a criterion standard diagnosis of delirium. According to the criterion standard diagnosis, delirium was present in 47 (14.9%) out of the 315 patients enrolled. The Nu-DESC shows a good specificity level of 91.0% (95% CI 87.0–94.2), but a moderate sensitivity level of 66.0% (95% CI 50.7–79.1). Positive and negative likelihood ratios are 7.37 (95% CI 4.77–11.36) and 0.37 (95% CI 0.25–0.56), respectively. In an exploratory analysis, we find that operationalizing the Nu-DESC item “disorientation” by specifically asking patients to state the day of the week and the name of the hospital unit would raise Nu-DESC sensitivity to 77.8%, with a specificity of 84.6% (positive and negative likelihood ratio of 5.05 and 0.26, respectively). The Nu-DESC shows good specificity but moderate sensitivity when performed by nurses during their daily work in a German ED. We have developed a modified Nu-DESC version, resulting in markedly enhanced sensitivity while maintaining a satisfactory level of specificity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Delirium is a frequent, yet often underestimated problem in emergency departments (EDs). It is characterized by an acute change in mental status with inattention, disorientation and cognitive impairment, and is especially prevalent in elderly people [1, 2]. Eight to 17% of elderly American and German patients present to the ED with delirium [3, 4]. However, only 11–46% of these are recognized as delirium cases by emergency physicians (EPs) [5], as the diagnosis is challenging. This especially applies to hypoactive delirium, the most frequent form of delirium in elderly ED patients [6, 7], which is often referred to as “silent,” since it does not draw the attention of ED personnel [7]. Patients in whom the delirium diagnosis is missed are at risk of inadequate treatment [8], or are sometimes even incorrectly discharged [9]. This can have fatal consequences, especially when delirium is precipitated by a life-threatening cause such as intoxication, ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage or encephalitis [2, 10]. Such patients require an immediate diagnosis of delirium, and subsequent treatment of the underlying disease. Therefore, as the gatekeeper of the hospital, the ED plays a critical role in diagnosing delirium as well as its underlying cause. Moreover, given the high prevalence and serious consequences of delirium in the elderly [4], every elderly patient admitted to the ED should be screened for this form of altered mental status. Diagnosing delirium relies considerably on observations of the patient’s behavior and mental performance. Since nurses are often the first to establish contact with patients in an ED, tend to spend more time with them than the EPs, and can adequately evaluate the patient’s course of disease, they play a critical role in the early detection of delirium [11]. To this aim, the Nursing Delirium Screening Scale (Nu-DESC) might serve as a feasible instrument for screening delirium in the ED [12]. It can be administered in less than 2 min [13] and is easily integrated into the nurses’ daily work routine. The Nu-DESC consists of five items calling for a description of the characteristics observed in the patient; this bypasses the need for having to perform an extensive examination of each patient. These items can already be evaluated and documented during the admission process in the ED. The Nu-DESC was developed by Geaudreau et al. in 2002, and originally validated in 146 oncology in-patients. Here, the confusion assessment method (CAM) is used as reference standard, where it demonstrates good sensitivity and specificity levels of 85.7% and 86.8%, respectively [11], and is in accordance with the DSM-IV criteria for delirium [11]. The Nu-DESC has been translated into many languages including German [14]. This version has previously been validated by trained research assistants in post-operative patients, where it shows a very good sensitivity (98%) and specificity (92%) levels [13]. When the Nu-DESC is conducted by trained staff members in an intensive care unit (ICU) setting, sensitivity is 83% and specificity 81% [15]. Given that both the ICU and ED are characterized by a high volume of critically ill patients, other delirium screening tools originally designed for the ICU have also been shown to be valid for the ED. Based on this notion, the Nu-DESC has been proposed as a potentially valid screening instrument for the ED [12], although so far this has not been directly tested.

The aim of our study is, therefore, to investigate the diagnostic performance of the German version of the Nu-DESC for delirium screening in an interdisciplinary German ED. The Nu-DESC was performed by an assigned nurse working under routine conditions, and then compared to a reference standard consisting of a psychiatrist’s or neurologist’s diagnosis based on DSM-5 criteria.

Methods

Study setting and population

This prospective observational study was conducted according to the STARD standards [16] and was approved by the Local Ethics Committee (no. 72/16). It was carried out in an interdisciplinary ED at a large university hospital that receives approximately 50,000 emergency patients each year. Written or verbal consent from the patients was not required as this is an evaluation-based study aiming for permanent implementation of the Nu-DESC for delirium screening in the ED. To ensure the best treatment for all patients, EPs were informed about the criterion standard diagnosis subsequent to the completion of all tests.

This study enrolled a convenience sample of emergency patients and was limited to the medical section of the department, where, unlike in the trauma section, patients tend to stay longer and, therefore, have a higher probability of going through all the necessary assessment procedures. The screening was performed from May to August 2016, Monday to Friday from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. The time interval was adapted to the availability of the consultant specialists. On the days with high patient turnover, we were not able to enroll all potentially eligible patients, due to the restricted availability of the consultant physicians. To keep selection bias to a minimum in this case, patients were enrolled consecutively, based on the time at which they were seen in triage. Patients were enrolled if they were at least 70 years old, and had been in the ED for less than 12 h at the point of screening. This broad time slot allowed the enrollment of patients who arrived at the ED during the night. Patients were excluded if there was no examination room available for assessment, or if they had to be placed in isolation rooms due to the risk of infection. Moribund patients were excluded for ethical reasons. Furthermore, patients were excluded if: they could not be assessed adequately; they were deaf, blind, nonverbal, non-German-speaking, or in a state of stupor/coma, or they had severe dementia. Severe dementia was ascertained if the patient had previously obtained a single digit Mini Mental-Status Examination (MMSE) score, or when evidence from medical records or surrogate interviews suggested that the patient lacked the ability to carry out basic personal care.

Study protocol

The Nu-DESC was performed by the nurse in attendance. Since the Nu-DESC is routinely used to screen and evaluate delirium on all the general wards and intensive care units at the Medical Center, University of Freiburg, the nursing staff was already familiar with this tool, and hence required only a short oral introduction before commencement of the study. The result of the Nu-DESC was compared to a reference standard consisting of a detailed delirium assessment by one of the four consultant psychiatrists and neurologists who worked on a rotation basis in the ED. Each of these consultants had at least 10 years’ experience working in a hospital setting, where assessing delirium was a routine part of their job. All examiners were blinded to the other test results.

Nu-DESC

The Nu-DESC was performed using the German version [14]. It consists of five items that assess the patient for the presence of disorientation (item 1), inappropriate behavior (item 2), inappropriate communication (item 3), illusions or hallucinations (item 4) and psychomotor retardation (item 5). Each item is appended with a more elaborate description and explanation of the corresponding clinical manifestation. The rating system was explained by an accompanying legend: zero points were given if the respective feature was not present. One point was given if the symptom was present and two points if it was exceptionally distinct. After careful observation and a non-standardized conversation with the patient, each nurse decided on a case-to-case basis whether the symptom characteristic should be evaluated with one or two points. The final Nu-DESC score ranged from zero to ten points, with a pre-specified cutoff of two or more points [11] corresponding to the presence of delirium. Upon completion of the Nu-DESC, the attending nurse noted the time needed to carry out the test, taking into account both the non-standardized communication or observations, and written documentation.

Criterion standard

The criterion standard consisted of a profound assessment of the patient by a consultant neurologist or psychiatrist. The same patients and criterion standard also served in a validation of the bCAM reported previously [17]. The consultant performed the 10–30 min assessment by adhering to a diagnostic report sheet, which was designed in advance to maximize inter-observer reliability. The report sheet contained a checklist for each of the five obligatory features of delirium that serve as prerequisites for its diagnosis, in line with the DSM-5 [1]. The DSM definition of delirium was chosen because it is the reference standard most frequently used to validate delirium screening instruments [11, 13, 15, 18]. The checklist required the examiner to successively evaluate these five items in the following order: (A) disturbance in attention or awareness (reduced orientation to the environment), (B) acute onset or fluctuating course, (C) additional disturbance in cognition, (D) disturbances not better explained by another pre-existing neurocognitive disorder, and (E) disturbance as a direct physiological consequence of another medical condition. Delirium was present if all five items were positive. Once an item did not apply, delirium was ruled out and the assessment was stopped. In the case of inconclusive test results, the consultant physician added further tests at his own discretion, such as a more detailed neurologic or psychiatric examination. Additionally, the consultant physicians included in their assessment the patient’s MMSE result, which was conducted shortly before the criterion standard assessment. Due to the consultant physician’s limited time availability, the MMSE was performed by a research assistant. For patients unable to complete all MMSE test items (for example, due to visual or motor impairment), the final test score was determined using linear transformation of the score that was actually reached [19]. If delirium was present according to the criterion standard, the consultant physician was asked to define the subtype of delirium as described in the DSM-5 [1], which then allowed a sub-analysis of the Nu-DESC diagnostic performance with respect to the different subtypes. Due to the time constraints faced by the consultants, inter-observer variability between the consultant physicians was not assessed.

Data collection

The patient’s test results were entered into an electronic data set once all the tests were completed. This task was performed by a research assistant, who for this purpose was not blinded to the data. The assistant also reviewed and entered the patient’s gender, age, and diagnosis at discharge, as documented in the final ED medical record. The purpose of this was to check for a potential selection bias in enrolled vs. excluded patients. In cases of several discharge diagnoses for one patient, we chose the one that best explained the patient’s main complaint, or, in the case of delirious patients, the one that best explained the genesis of delirium. For delirious patients, the final diagnoses were double-checked by a senior physician, who also took into account the final discharge letter from the hospital, if available. The Emergency Severity Index (ESI) was taken from electronic patient records and registered as a marker for the patient’s severity of illness. The ESI is defined during the triage process to stratify the urgency for treatment in the ED from least urgent (ESI 5) to most urgent (ESI 1) [20]. The Acute Physiology Score (APS) was calculated for all enrolled patients. It is part of the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II and allows quantification of the severity of illness, with higher scores indicating a higher severity of illness [21]. Missing data were documented as such in the database as well as in the tables and figures. In the case where data from a particular patient were not available for an analysis, the patient was excluded and the final number of patients included in the analysis was stated.

Data analysis

For continuous variables with normal distribution, measures of central tendency and range of dispersion are reported as mean values with a 95% confidence interval (CI), while continuous variables with non-normal distribution are reported as median and interquartile ranges (IQR). For categorical variables, we calculated absolute numbers and proportions. The statistical significance of continuous variables was evaluated using the t test (normal distribution), Mann–Whitney U test (non-normal distribution), or Fisher’s exact test (categorical variables). For variables with multiple comparisons, adjusted p values were calculated using Bonferroni correction. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to test for normal distribution. Significance was set at a p value < 0.05. By assuming that elderly patients in German EDs have a 14% prevalence of delirium [3], we found that a sample size of at least 200 patients was required to reliably assess the diagnostic performance of the Nu-DESC. Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative likelihood ratios (LR + , LR −), odds ratio (OR), and accuracy were calculated with 95% CI for the Nu-DESC and compared to criterion standard findings. Among the patients with delirium, we performed a descriptive comparison of the two groups of patients with true-positive vs. false-negative Nu-DESC test results, examining the following factors that potentially influenced detection rate: delirium subtype, the duration of the Nu-DESC testing, and the time interval between the Nu-DESC and criterion standard assessments. We also performed a multivariable logistic regression analysis to examine the influence of age, APS, and the presence of dementia on Nu-DESC sensitivity and specificity. Patients were only included in this analysis if data were available for all the covariates mentioned above. Kappa statistics were calculated for the assessment of feature “disorientation”, which was the only Nu-DESC feature that was assessed by predefined questions (part of the MMSE) in the criterion standard (see description of the “Criterion standard”). This parameter was used to estimate inter-observer reliability between nurses and physicians for the reference standard. Disorientation was considered present in the criterion standard if the patient made ≥ 1 error in the ten questions of the MMSE assessing disorientation. The level of agreement was rated according to Landis and Koch [22]. In a secondary analysis, we attempted to standardize Item 1 (disorientation) of the Nu-DESC, with the aim of increasing the overall diagnostic performance. We, therefore, calculated the sensitivity, specificity and accuracy for different versions of a modified Nu-DESC consisting of items 2–5 of the original Nu-DESC; however, instead of considering the non-standardized patient’s test result for item 1 (disorientation), this item was replaced by two out of the ten items used on the MMSE to evaluate the patient’s orientation in terms of place and time. We chose to include a combination of two MMSE Items in the modified Nu-DESC version, as this would allow a gradation in the allocation of points; i.e., 0 points if both questions were answered correctly, 1 point for 1 wrong answer, and 2 points when both questions were answered incorrectly. The correct order of questions in items 1–10 were: year, time of the year, exact date, day of the week, month, country, federal state, city, name of hospital, name of unit. For the answer to the exact date question, a deviation of ± 1 day was accepted. The calculation was performed for each possible combination of two MMSE Items. Since we looked for the best screening performance, the best modified Nu-DESC was identified by choosing the one with the best sensitivity, while still having acceptable specificity and accuracy. All data analyses were performed using IBM SPSS statistics 23 software (IBM Corp., IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0, Armonk, NY) and MedCalc for Windows, version 17.9.2 (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium).

Results

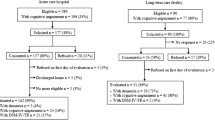

During the recruitment period, 673 patients aged 70 or above were screened for the inclusion criteria; 358 of these patients were subsequently excluded (see Fig. 1). A total of 315 patients were ultimately enrolled (Table 1). The median age was 78, and 53.7% were female. Enrolled vs. excluded patients are similar in age and gender (Table 1). Only patients with an ESI of 4 were significantly more likely to be excluded (p = 0.015).However, the median ESI is the same for both groups (ESI = 3). There is also a significant difference in the diagnosis category of enrolled vs. excluded patients, where cardiovascular patients were more likely to be included in the study (p = 0.036) (Table 1). Of the 315 patients enrolled, delirium was identified in 47 (14.9%), based on the consultant’s criterion standard diagnosis. Most delirium cases were manifest as the hypoactive subtype (26 patients), while 14 patients displayed mixed-type delirium and only three patients displayed hyperactive delirium. In four cases, the consultant specialists were unable to define a motor subtype (“no motor subtype”) [7]. The Nu-DESC took a median time of 1 min (IQR 1–2 min) (n = 300; data missing from 15 patients) and the median time between the completion of each of the Nu-DESC and criterion standard tests was 59 min (IQR 22.5–105.5 min) (n = 309, data was missing for six patients). The diagnostic performance of the Nu-DESC is summarized in Table 2. Given that a test result of ≥ 2 points was required for the diagnosis of delirium, the Nu-DESC shows a specificity of 91.0% (95% CI 87.0–94.2), whereas sensitivity is 66.0% (95% CI 50.7–79.1). LR + and LR − were 7.37 (95% CI 4.77–11.36) and 0.37 (95% CI 0.25–0.56), respectively. When compared to criterion standard diagnostics, Nu-DESC results are true positive for 31 patients, false negative for 16 patients, false positive for 24 patients and true negative for 244 patients. The nurses’ evaluation also reveals that patients with delirium are mostly positive for the Nu-DESC items 1, 3 and 5. Among the delirium subtypes, all three patients with hyperactive delirium and 11/14 patients with mixed-type delirium were correctly identified by the Nu-DESC. However, the hypoactive subtype was only correctly identified in 14 out of 26 patients. The median duration of the Nu-DESC test did not significantly differ between the delirium patient groups with true-positive (n = 28) vs. false-negative (n = 14) Nu-DESC results (p = 0.26), nor was there a significant difference in the median time interval between the Nu-DESC and criterion standard assessment (n = 31) (p = 0.18). The multivariable logistic regression including 314 patients (one patient was excluded because the APS could not be calculated) shows no effect of age, APS, or presence of dementia on Nu-DESC sensitivity, nor did age or APS have any influence on Nu-DESC specificity. However, Nu-DESC specificity significantly increases when dementia is present [p < 0.001, OR: 15.91 (95% CI 3.29–76.89)]. Cohen’s kappa for the shared Nu-DESC and criterion standard item of disorientation show a fair accordance between nurses and consultant specialists (ĸ = 0.36). Of the 312 patients whose MMSE tests could be included in this sub-analysis, 60 (19.2%) were not deemed by the nurses to be in a state of disorientation, despite showing disorientation in the MMSE. Furthermore, nurses found no signs of disorientation in 14 of the 16 false-negative Nu-DESC patients. We, therefore, hypothesized that a standardized approach to determining orientation using the default items of the MMSE orientation section could improve Nu-DESC performance; here, sensitivities, specificities, accuracies of each possible modified Nu-DESC version were calculated with the different combinations of two out of the ten MMSE Items that refer to orientation. Consequently, we obtained results for 45 different combinations of modified Nu-DESCs, which are shown in the supplementary section (S1). The best levels of sensitivity are observed in modified Nu-DESCs that include MMSE item 4 + 10 (day of the week + name of hospital unit) or item 3 + 10 (exact date + name of the unit) (both 77.8%), followed by item 3 + 4 (exact date + day of the week), and item 1 + 10 (year and name of hospital unit) (both 75.6%) (Table 3). Based on these results, a modified Nu-DESC that includes Items 4+10 of the MMSE would reach a sensitivity of 77.8% and a specificity of 84.6%; LR + was 5.05 and LR − 0.26 (Table 4).

Discussion

The high prevalence and severe consequences of delirium among elderly emergency patients call for a systematic screening process in the ED. The Nu-DESC has previously shown good validity both in the ICU and post-operative care settings. Moreover, due to it being a fast and simple test mainly based on observations and non-standardized communication that can be carried out during the admission process, it has also been proposed as a feasible delirium screening instrument for the ED that can be applied by nursing staff. In this context, a positive Nu-DESC result would not confirm, but raise the possibility of delirium being present in a patient. Those patients would then have to undergo elaborate diagnostics by a physician. Our study is the first to validate the diagnostic performance of the Nu-DESC for screening delirium in elderly ED patients when it is applied during the daily work routine. We observe a good specificity (91.0%); however, the sensitivity level is only moderate (66.0%). Other studies conducted in ICU, post-cardiac surgery and normal ward settings confirm our observation, although it stands in contrast to the good diagnostic performance of the Nu-DESC in post-operative and ICU settings [15, 23, 24]. There are several potential reasons for the moderate sensitivity observed in the present study. In accordance with previous studies, we find that while the Nu-DESC shows good diagnostic performance each for hyperactive and mixed-type delirium, hypoactive delirium is not recognized in many patients [23, 24], despite it being the most prevalent type in elderly ED patients [6]. Therefore, Nu-DESC sensitivity might be improved by providing additional training to nurses who carry out the Nu-DESC assessment [23], with particular focus on the evaluation of the items ‘psychomotor retardation’ and ‘disorientation’ in order to detect more cases of hypoactive delirium [24]. Furthermore, it was previously reported that nurses consider the Nu-DESC items insufficiently defined [25]. This is also reflected by the modest inter-rater reliability observed in several studies, even when the Nu-DESC assessment is performed by trained nurses or research staff (ĸ = 0.47–0.68) [15, 25]. It should be noted, however, that inter-observer reliability for the Nu-DESC was not calculated in the present study as this would have exceeded the capacity of both the patients and nurses. However, we did compare the disorientation item, which was assessed both in the Nu-DESC by the nurses and in the criterion standard diagnosis by the consultant physicians; here, a low level of accordance (ĸ = 0.36) was found between the Nu-DESC and the criterion standard. Furthermore, based on the Nu-DESC assessment, disorientation is not considered to be present in 60 patients who in contrast fail on at least one of the ten MMSE items. This led us to the conclusion that Nu-DESC sensitivity might be improved by operationalizing the assessment of disorientation (Nu-DESC Item 1). This was the objective of our exploratory analysis, where we aimed to identify the two disorientation-related MMSE items that would most significantly increase Nu-DESC sensitivity. We find that asking the patients to state the day of the week and the name of the hospital unit (MMSE items 4 and 10) would considerably increase sensitivity from 66.0 to 77.8%, while maintaining high specificity (84.6%). This renders the modified Nu-DESC a potentially useful instrument for screening delirium in the ED, without considerably lengthening the duration of the procedure.

The modified Nu-DESC described here is equivalent to the results of other short-duration delirium screening tools (< 5 min) that have been validated for the ED [3] (sensitivities of 68.0–82.0% and specificities of 87.6–98.6%) [17, 18, 26,27,28]. The Delirium Triage Screen has excellent sensitivity (98.0%), but moderate specificity (55%) when performed by EPs and research assistants [18]. Both the 6-Item Cognitive Impairment Test (6-CIT) and the 4AT were recently validated for the ED, each showing good levels of sensitivity and specificity when performed by research staff (6-CIT: sensitivity 89%, specificity 74%; 4AT: sensitivity 93%, specificity 91%) [29]. Apart from our Nu-DESC validation study, only a few nurse-led delirium screening scales have been validated for the ED. The mRASS, a scale looking at level of agitation and sedation, shows moderate performance (sensitivity 70%, specificity 93%) when conducted by specially trained nurses exempted from other clinical duties during the study [30]. The mCAM-ED also shows good performance (sensitivity 90%, specificity 98%) [31], but consists of several performance tasks that can take up to 6 min to be administered [31].

The major strength of our results is the naturalistic setting of the study in which patients in the ED were screened by the assigned nurses under normal working conditions, rather than by research staff under pre-determined conditions. This may well have an important influence on performance, given that we recently demonstrated that the results of a delirium screening study under research conditions could not be replicated under routine work conditions [17]. The modified Nu-DESC might, therefore, serve as a good alternative that can be implemented widely and might even show better performance when nurses are trained for its optimal application.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study that should be noted. Due to the limited availability of nurses and consultant neurologists and psychiatrists, we were not able to include all potentially eligible patients in our study. This may have caused selection bias, which we otherwise tried to keep to a minimum by consecutively enrolling the study patients. We also did not screen patients during the night, when the incidence of delirium can be especially frequent [1]. However, the broad enrollment window of 12 h allowed the inclusion of many of the patients who had arrived at the ED during the night. The 3-h time window for each test performance (Nu-DESC and criterion standard assessment) was chosen to best fit in with the nurses’ and consultant physicians’ respective work routines. While this approach allowed us to include more patients in our study, it might have also resulted in non-conformant test results, due to a shift in the patient’s delirium symptoms. Therefore, the diagnostic performance of the Nu-DESC would have the potential to be higher if the Nu-DESC and criterion standard assessment were performed in direct succession. Furthermore, the MMSE as part of the criterion standard assessment was performed by a research assistant due to the consultant’s time constraints. We find some differences between the groups of enrolled and excluded patients, in terms of their diagnoses and severity of illness. These were represented by the ESI score, whereby patients with an ESI 4 are more likely to be excluded from the study; indeed, this might have caused a spectrum bias, resulting in an overestimation of Nu-DESC sensitivity [32]. ESI four patients were often excluded because they were asked to wait in the hallway due to the unavailability of an examination room. However, there are other validation studies for delirium screening tools that have reported the same spectrum bias, but found no effect on screening sensitivity [18]. Given that moribund patients were selectively excluded, this could have resulted in a shift away from hypoactive delirium, which might have had an impact on the sensitivity and specificity of the Nu-DESC. This study was conducted in a single German-speaking ED and the Nu-DESC was performed in elderly medical patients. Therefore, our findings might not be directly applicable to other settings or patient groups. The diagnostic performance of our modified Nu-DESC design is based on the data obtained during the study period and hence requires confirmation by external validation in a prospective study. It should also be noted that the MMSE items proposed for the modified Nu-DESC were not assessed by the nurses, but rather by a research assistant who performed the MMSE shortly before the nurses’ assessment. However, we believe that asking two short, predefined questions about orientation is not likely to result in relevant differences between the nurses and research assistant. A future study should, therefore, validate the modified Nu-DESC when it is performed entirely by nurses. Ideally, this study should also investigate the interobserver-reliability by having at least two nurses assess each patient. Also, other delirium screening tests should be performed concurrently and be compared to the modified Nu-DESC to prove its additional benefit.

Conclusion

The Nu-DESC is a short delirium screening tool that can be performed within 1 min by a nurse during the patient’s admission to the ED. It shows good specificity but only moderate sensitivity when conducted in elderly medical patients in a German ED. The moderate sensitivity of the test can potentially be improved by providing nurses with extra training and applying a modified version of the Nu-DESC in which the assessment of disorientation (Item 1) is operationalized by asking two predefined questions about the day of the week and the name of the hospital unit. With such a modification, the Nu-DESC might address the urgent need for systematic delirium screening in German EDs by serving as an instrument with a sufficient diagnostic performance.

References

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edn. American Psychiatric Association, Arlington

Han JH, Wilber ST (2013) Altered mental status in older patients in the emergency department. Clin Geriatr Med 29(1):101–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2012.09.005

Singler K, Thiem U, Christ M et al (2014) Aspects and assessment of delirium in old age. First data from a German interdisciplinary emergency department. Z Gerontol Geriatr 47(8):680–685

Inouye SK, Westendorp RGJ, Saczynski JS (2014) Delirium in elderly people. Lancet 383(9920):911–922. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60688-1

Barron EA, Holmes J (2013) Delirium within the emergency care setting, occurrence and detection: a systematic review. Emerg Med J 30(4):263–268. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2011-200586

Han JH, Zimmerman EE, Cutler N et al (2009) Delirium in older emergency department patients: recognition, risk factors, and psychomotor subtypes. Acad Emerg Med 16(3):193–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00339.x

Meagher D (2009) Motor subtypes of delirium: past, present and future. Int Rev Psychiatry 21(1):59–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540260802675460

Kennedy M, Enander RA, Tadiri SP et al (2014) Delirium risk prediction, healthcare use and mortality of elderly adults in the emergency department. J Am Geriatr Soc 62(3):462–469. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.12692

Hustey FM, Meldon SW, Smith MD et al (2003) The effect of mental status screening on the care of elderly emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med 41(5):678–684. https://doi.org/10.1067/mem.2003.152

Park JM, Stern TA (2010) Delirious patients. In: Stern TA, Fricchione GL, Cassem Ned (eds) Massachusetts General Hospital handbook of general hospital psychiatry, 6th edn. Elsevier/Saunders, Philadelphia, pp 93–104

Gaudreau J-D, Gagnon P, Harel F et al (2005) Fast, systematic, and continuous delirium assessment in hospitalized patients: the nursing delirium screening scale. J Pain Symptom Manag 29(4):368–375

Han JH, Wilson A, Ely EW (2010) Delirium in the older emergency department patient: a quiet epidemic. Emerg Med Clin North Am 28(3):611–631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emc.2010.03.005

Radtke FM, Franck M, Schust S et al (2010) A comparison of three scores to screen for delirium on the surgical ward. World J Surg 34(3):487–494. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-009-0376-9

Lütz A, Radtke FM, Franck M et al (2008) Die Nursing Delirium Screening Scale (Nu-DESC)—Richtlinienkonforme Übersetzung für den deutschsprachigen Raum (The Nursing Delirium Screening Scale (NU-DESC)). Anasthesiol Intensivmed Notfallmed Schmerzther 43(2):98–102. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2008-1060551

Luetz A, Heymann A, Radtke FM et al (2010) Different assessment tools for intensive care unit delirium: which score to use? Crit Care Med 38(2):409–418. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181cabb42

Cohen JF, Korevaar DA, Altman DG et al (2016) STARD 2015 guidelines for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies: explanation and elaboration. BMJ Open 6(11):e012799. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012799

Baten V, Busch H-J, Busche C et al (2018) Validation of the brief confusion assessment method for screening delirium in elderly medical patients in a German emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.13449

Han JH, Wilson A, Vasilevskis EE et al (2013) Diagnosing delirium in older emergency department patients: validity and reliability of the delirium triage screen and the brief confusion assessment method. Ann Emerg Med 62(5):457–465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.05.003

Busse A, Sonntag A, Bischkopf J et al (2002) Adaptation of dementia screening for vision-impaired older persons: administration of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). J Clin Epidemiol 55(9):909–915

Gilboy N, Tanabe T, Travers D et al (2011) Emergency Severity Index (ESI): A triage tool for emergency department care, version 4. Implementation handbook 2012 edition. AHRQ Publication, 12-0014. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville

Knaus WA, Draper Elizabeth A, Wagner Douglas P, Zimmerman JE (1985) APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med 13(10):818–829

Landis JR, Koch GG (1977) The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33(1):159–174

Lingehall HC, Smulter N, Engström KG et al (2013) Validation of the Swedish version of the Nursing Delirium Screening Scale used in patients 70 years and older undergoing cardiac surgery. J Clin Nurs 22(19–20):2858–2866. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04102.x

Hargrave A, Bastiaens J, Bourgeois JA et al (2017) Validation of a nurse-based delirium-screening tool for hospitalized patients. Psychosomatics 58(6):594–603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psym.2017.05.005

Poikajärvi S, Salanterä S, Katajisto J et al (2017) Validation of Finnish Neecham Confusion Scale and Nursing Delirium Screening Scale using confusion assessment method algorithm as a comparison scale. BMC Nurs 16:7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-016-0199-6

Tamune H, Yasugi D (2017) How can we identify patients with delirium in the emergency department? A review of available screening and diagnostic tools. Am J Emerg Med 35(9):1332–1334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2017.05.026

Han JH, Wilson A, Graves AJ et al (2014) Validation of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit in older emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med 21(2):180–187. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.12309

Han JH, Vasilevskis EE, Schnelle JF et al (2015) The diagnostic performance of the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale for detecting delirium in older emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med 22(7):878–882. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.12706

O’Sullivan D, Brady N, Manning E et al (2018) Validation of the 6-Item Cognitive Impairment Test and the 4AT test for combined delirium and dementia screening in older Emergency Department attendees. Age Ageing 47(1):61–68. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afx149

Grossmann FF, Hasemann W, Kressig RW et al (2017) Performance of the modified Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale in identifying delirium in older ED patients. Am J Emerg Med 35(9):1324–1326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2017.05.025

Hasemann W, Grossmann FF, Stadler R (2017) Screening and detection of delirium in older ED patients: performance of the modified confusion assessment method for the Emergency Department (mCAM-ED). A two-step tool. Intern Emerg Med. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-017-1781-y

Kohn MA, Carpenter CR, Newman TB (2013) Understanding the direction of bias in studies of diagnostic test accuracy. Acad Emerg Med 20(11):1194–1206. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.12255

Acknowledgements

We thank all the Emergency Department nurses at the University Hospital of Freiburg who performed the Nu-DESC. We also thank Susanne Weber, MSc, (Institute of Medical Biometry and Statistics, Medical Faculty and Medical Center, University of Freiburg) for advice on the data analysis.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research involving human and/or animal participants

The study was approved by the Local Ethics Committee (No. 72/16). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

If possible, oral informed consent was obtained directly from the patient or an authorized proxy. According to our local ethics committee written or verbal consent from the patients was not required as this was an evaluation-based study aiming for permanent implementation of the Nu-DESC for delirium screening in the ED. In order to ensure the best treatment for all patients, EPs were informed about the criterion standard diagnosis subsequent to the completion of all tests.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brich, J., Baten, V., Wußmann, J. et al. Detecting delirium in elderly medical emergency patients: validation and subsequent modification of the German Nursing Delirium Screening Scale. Intern Emerg Med 14, 767–776 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-018-1989-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-018-1989-5