Abstract

The purpose was to examine the association between e-cigarette use and smoking cessation according to quit duration in Greece in 2017. A cross-sectional survey of a representative sample of adults living in Attica prefecture was performed in May 2017 through telephone interviews. The present analysis was confined to current and former smokers (n = 2568). Logistic regression analyses were performed with current and current daily e-cigarette use being the dependent variables and demographics and smoking status (current smokers vs smoking cessation for ≤ 12 months, 13–36 months, 36–72 months, and > 72 months) being independent variables. Almost half of former smokers (47.7%) had quit smoking for ≤ 72 months. Current e-cigarette use was more prevalent among former smokers of ≤ 12 months (26.2%) and 13–36 months (27.0%), and was rare among former smokers of > 72 months (1.0%). Current e-cigarette use was strongly associated with smoking cessation for ≤ 12 months (OR 6.12, 95% CI 4.11–9.10, P < 0.001) and 13–36 months (OR 6.28, 95% CI 4.25–9.28, P < 0.001). Current daily e-cigarette use was also strongly associated with smoking cessation for ≤ 12 months (OR 10.41, 95% CI 6.56–16.53, P < 0.001) and 13–36 months (OR 11.18, 95% CI 7.12–17.55, P < 0.001). Current and current daily e-cigarette use were not significantly associated with smoking cessation for 37–72 months, and were negatively associated with smoking cessation for > 72 months. Current and current daily e-cigarette use are strongly associated with recent smoking cessation in Greece, suggesting a positive public health impact in a country with the highest prevalence of smoking in the European Union. E-cigarettes do not appear to promote relapse in long term former smokers. Duration of smoking cessation and frequency of e-cigarette use should be taken into consideration when examining the association between e-cigarette use and smoking cessation in population studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The rapid growth in awareness and use of electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) in recent years has generated substantial controversy within the public health community. One of the issues that has divided scientists is whether e-cigarette use promotes or prevents smoking cessation, with studies showing conflicting results [1]. Randomized-controlled trials have shown that e-cigarettes have no or at best modest positive effects on smoking reduction and cessation [2,3,4,5], while cohort studies have shown conflicting results [6,7,8]. Many studies have been criticized for suffering from limitations and bias that compromise the validity of the outcome [9]. In addition, e-cigarette use represents a behavioral intervention and a lifestyle change, related to the substitution of a habit (smoking) with another, similar in rituals, habit (e-cigarette use), with the product choice and use patterns for the latter being based on self-preference and satisfaction [10]. Therefore, the conventional research methodologies, which are mostly suitable for pharmacological interventions, may be inappropriate to realistically determine the effects of e-cigarettes on smoking cessation. Considering these limitations, a potentially important tool for monitoring the public health impact of e-cigarettes is to record the population use of e-cigarettes, specifically the patterns of use, use by smokers vs. never smokers, and the association between e-cigarette use and the smoking status of users.

Greece is a country with high prevalence of smoking. The 2017 Eurobarometer survey reports that Greece has the highest prevalence of smoking in the European Union (EU) among people aged ≥ 15 years, at 37% [11]. A recent study by our group reports a smoking prevalence of 32.6% among adults in the largest prefecture in Greece [12]. Although the country follows the EU directives on tobacco control and introduced smoking bans and tax increases on tobacco products in 2009, the tobacco control efforts have stalled in the years of fiscal crisis [13]. No country-wide anti-smoking campaigns have been organized in recent years, the public place smoking bans are not strongly enforced and, as a result, Greece is ranked 31st among 35 European countries in the Tobacco Control Scale [14]. E-cigarettes are available in Greece, in both retail stores and online, and became popular since 2010–2011. The EU 2014 Tobacco Products Directive on these products was implemented into national legislation in 2016 together with an additional measure of banning use in closed public places. A recent population-representative study reported that 5.0% of the adult Greek population are current e-cigarette users, with the vast majority of them (98.5%) being current and former smokers [12]. The present study expands on the previous analysis by examining the association between e-cigarette use and smoking cessation among participants with a history of smoking, with a particular focus on the timing of smoking cessation.

Methods

Design, setting, and participants

The study design and methodology has been previously presented [12]. In brief, Computer-Assisted Telephone Interviews (CATI) were performed in May 2017 in a sample of 4058 respondents aged ≥ 18 years. The population of the survey was inhabitants in the Attica prefecture, which hosts 35% of the total adult population of Greece according to Census 2011 (http://www.statistics.gr/en/2011-census-pop-hous). The sample was representative of the prefecture of Attica population, with all registered landline phone numbers being used as the sampling frame. The sample design was stratified random sampling. Further post-survey adjustment weights were applied to depict sample composition as the actual population demographics.

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Onassis Cardiac Surgery Center (reference nr: 591/14.12.16). All participants provided verbal consent at the beginning of the interview to participate to this study.

Definitions and measurements

Sociodemographic factors

The age of the participants was coded into five categories (18–24, 25–39, 40–54, and 55 years and older). Education was coded as “high school or less”, “technical education”, “university education”, and “postgraduate education”. Marital status was categorized as “single”, “married/living with a partner”, and “widowed/divorced”. The self-assessed financial status of participants was recorded, with response options being “We are unable to cope with our household finances” (very bad financial situation), “We are able to cope with our household finances, but with a lot of difficulties” (bad financial situation), “We are able to cope with our household finances, but without the ability to save a lot of money (not good financial situation), and “We don’t have financial problems” (good financial situation).

Smoking and e-cigarette use

Participants were classified according to their smoking status as current smokers, former smokers, and never smokers. The present study analyzed current and former smokers only. For former smokers, a question was asked to determine the duration of smoking cessation: “How many months ago did you quit smoking?” The number of months was recorded according to self-recollection and the responses were subsequently recoded as smoking cessation for ≤ 12 months, 13–36 months, 37–72 months, and > 72 months. The classification was based on the fact that e-cigarettes became popular in Greece starting in 2010–2011.

E-cigarette awareness was assessed by asking: “Have you ever heard of e-cigarettes?” Participants who were not aware of e-cigarettes were classified as never e-cigarette users and were included in the analysis. Current e-cigarette use status was assessed by asking: “Regarding the use of e-cigarettes which of the following statements applies to you?” Response options were: “I currently use e-cigarettes” (current use), “I used them in the past, but no longer use them” (past use), and “I tried them in the past only once or twice” (past experimentation) and “I have never used them” (never use). Current users were asked to report whether they were using e-cigarettes daily (current daily e-cigarette use) or occasionally.

Statistical analysis

All values were presented as weighted proportions with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The analyses were performed among current and former smokers. Demographic characteristics of the two groups were compared using crosstabulations and Pearson's Chi-square test. Current and current daily e-cigarette use frequency was compared between smoking status groups using crosstabulations and Pearson’s Chi-square test with post hoc comparisons (z test) with Bonferroni correction. Two separate logistic regression analyses were performed to assess the association between current e-cigarette use and smoking cessation (reported as OR, 95% CI). The dependent variable was current vs. all other use (which included past use, past experimentation, and never use) in one model and current vs. never e-cigarette use in the other model (participants reporting past use and past experimentation were excluded). Similarly, two logistic regression analyses assessed the association between current daily e-cigarette use (current daily vs. all other use in one model and current daily vs. never use in the other) and smoking cessation. In all models, independent variables included demographics (age, gender, education, financial status, and marital status) and smoking status. For the latter variable, current smoking was coded as 1 (referent), smoking cessation for ≤ 12 months as 2, smoking cessation for 13–36 months as 3, smoking cessation for 37–72 months as 4, and smoking cessation for > 72 months as 5. Additional logistic regression analyses were performed without classifying former smokers according to duration of smoking cessation; the smoking status was introduced as independent variable with current smoking coded as 1 and former smoking coded as 2. The purpose of this analysis was to identify how the results are affected when the duration of quitting is not included in the models. Demographics were also included as independent variables in these models, but ORs are presented only for the smoking status. All analyses were weighted and were performed with commercially available software (SPSS v.25.0, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Smoking and e-cigarette use in the population of Attica

The demographic characteristics of the two groups are presented in Table 1. From 4058 participants in the study, 2568 subjects (1287 former smokers and 1281 current smokers) were analyzed. More former smokers were males, and > 55 years old and fewer were single compared to current smokers. Approximately half of former smokers reported having quit > 72 months from the time of the survey. Of those who had quit for ≤ 12 months, 59.4% (95% CI 52.7–66.1%) had quit for ≥ 6 months.

Table 2 presents the patterns of e-cigarette use among current and former smokers, with the data on former smokers presented according to the duration of smoking cessation. Statistically significant differences were observed in current e-cigarette use prevalence between groups (P < 0.001). Approximately 1 out of 20 current smokers were current e-cigarette users. In contrast, more than one out of four former smokers of ≤ 12 months and 13–36 months were current e-cigarette users. E-cigarette use was rare among former smokers of > 72 months. From post hoc analysis (z test), current e-cigarette use was significantly more prevalent in former smokers of ≤ 12 and 13–36 months compared to all other groups, and was least prevalent in former smokers of > 72 months (P < 0.001 for all).

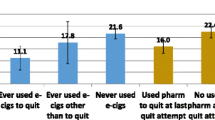

Figure 1 displays the prevalence of current daily e-cigarette use according to the smoking status. The findings were similar to current e-cigarette use, with post hoc analysis, showing that current daily e-cigarette use was significantly more prevalent in former smokers of ≤ 12 and 13–36 months compared to all the other groups (P < 0.001). It was least prevalent in former smokers of > 72 months, although no statistically significant difference was observed between this group and current smokers.

Table 3 presents the logistic regression analyses for current e-cigarette use. Current e-cigarette use was positively associated with smoking cessation irrespective of quitting duration. When former smokers were sub-classified according to quitting duration, current e-cigarette use was associated with approximately sixfold higher chance of smoking cessation for ≤ 12 months and 13–36 months compared to any other pattern of e-cigarette use (including never use). Compared to never e-cigarette users, current e-cigarette use was associated with approximately fivefold and fourfold higher chance of smoking cessation for ≤ 12 months and 13–36 months, respectively. In contrast, current e-cigarette users were significantly less likely to be former smokers of > 72 months.

Table 4 presents the logistic regression analyses for current daily e-cigarette use. The findings were similar to current e-cigarette use, but stronger associations were observed. When former smokers were sub-classified according to quitting duration, current e-cigarette use was associated with approximately tenfold higher chance of smoking cessation for ≤ 12 months and elevenfold higher chance of smoking cessation for 13–36 months compared to any other pattern of e-cigarette use (including never use). A negative association was found between current daily e-cigarette use and smoking cessation for > 72 months.

Other factors that were associated with current and current daily e-cigarette use included gender and age. A consistent positive association between e-cigarette use and male gender was found in all models. Age groups 18–24 and 25–39 years were more likely to be current and current daily e-cigarette users compared to age group ≥ 55 years. No association was found between e-cigarette use and education, marital status, and financial situation.

Discussion

This study presents the first evidence on the association between e-cigarette use and self-reported smoking cessation and quit duration in Greece. The study identifies a strong positive association between current e-cigarette use and recent smoking cessation (≤ 36 months). In contrast, a negative association is observed with smoking cessation of > 72 months. The study also shows the importance of considering duration of smoking cessation in accurately identifying the association between e-cigarette use and smoking cessation.

It is noteworthy that almost half of former smokers in the study sample had quit smoking over the past 72 months and approximately one-third had quit in the last 3 years. A study of a population-representative sample in the United States (US) found that 22.1% of former smokers had quit smoking during the past 3 years [15]. This indicates that there is substantial progress in smoking cessation in Greece over the last few years, since e-cigarettes became popular. While we cannot substantiate that e-cigarettes are the reason for the higher smoking cessation rates in recent years, a strong positive association was observed between current e-cigarette use and being a recent former smoker. This provides indirect evidence that the progress in smoking control could be at least partially attributed to the rising popularity and use of e-cigarettes. Moreover, the associations between e-cigarette use and smoking cessation were much stronger for recent quitters than for former smokers without considering the duration of quitting. The previously mentioned US study found that smoking cessation is negatively associated with being a daily e-cigarette user when duration of quitting was not taken into consideration [15].

The strong negative association between current e-cigarette use and quitting for > 72 months might be explained by the unavailability and low popularity of e-cigarettes in the previous years, and by the ineffective design, performance, and nicotine delivery of old e-cigarette products [16]. The former seems to be a more plausible explanation and contributing factor, considering that the vast majority of former smokers of > 72 months have not even tried e-cigarettes, while only 1% of them were current e-cigarette users. This finding is reassuring that e-cigarettes are not promoting relapse to nicotine use or use of an inhalational habit among long-term former smokers, which is in agreement with findings in the US [15]. A recent study analyzing the 2014 Eurobarometer survey reported a negative association between e-cigarette use and smoking cessation, but the survey did not include any information on smoking cessation duration [17]. Our findings herein emphasize the need to include the duration of smoking cessation in evaluating the effects of e-cigarettes in population studies.

The associations between e-cigarette use and smoking cessation were stronger when current e-cigarette use was compared to all other patterns of use (former use, former experimentation, and never use) than when current e-cigarette use was compared to never use. While it is possible that some former e-cigarette users may have quit both smoking and e-cigarette use, this suggest that most former users and experimenters of e-cigarettes represent failures to quit smoking or interest in experimenting with these products instead of using them in a determined smoking cessation attempt. However, the strongest associations with recent smoking cessation were observed for daily e-cigarette use, indicating the importance of examining frequency of use. This is expected considering previous observations that current e-cigarette use (usually defined as any use in the past 30 days) includes a lot of recent experimenters [18], and that frequency of use is positively associated with both quit attempts and quit success [7, 19].

Males were consistently more likely to be current and current daily e-cigarettes compared to females. This is consistent with an analysis of the 2014 Eurobarometer survey in which males were more likely to be current daily and current daily nicotine e-cigarette users [20]. A systematic review of differences in e-cigarette use between sociodemographic groups also found that awareness, ever and current e-cigarette use were more prevalent in males than females [21]. Our finding could be explained by the fact that more males were current and former smokers compared to females. However, there may be other reasons for this observation, such as different attributions for maintenance of e-cigarette use related to positive or negative reinforcement, different reasons for initiating e-cigarette use, and different expectancies about e-cigarettes between genders [22]. Education and financial status were not associated with e-cigarette use, a finding that is consistent with some [20, 23,24,25] but not all the previous observations [26, 27].

Limitations of this study are the inherent weaknesses of cross-sectional studies. The smoking status was self-reported and not objectively verified. However, this is common for large population studies. There is a possibility for recall bias on the duration of smoking cessation. Finally, the associations reported herein cannot be considered as definite proof for a causal link between e-cigarette use and smoking cessation.

In conclusion, statistically significant associations were observed between e-cigarette use and recent smoking cessation in Greece. The associations were stronger for recent (≤ 3 years) smoking cessation, which is compatible with the rising popularity of e-cigarettes, and for daily e-cigarette use. The findings suggest a positive public health impact of e-cigarettes in Greece, assuming that e-cigarettes helped these people quit smoking. It is possible that e -cigarettes have contributed to the increased proportion of former smokers in recent years, and this should be considered by the Greek health and regulatory authorities in developing appropriate policies that can maximize potential benefits and minimize unintended consequences. Duration of smoking cessation and frequency of e-cigarette use should be considered when assessing the impact of e-cigarette use in population studies.

References

Farsalinos K (2018) Electronic cigarettes: an aid in smoking cessation, or a new health hazard? Ther Adv Respir Dis 12:1753465817744960

Caponnetto P, Campagna D, Cibella F, Morjaria JB, Caruso M, Russo C et al (2013) EffiCiency and Safety of an eLectronic cigAreTte (ECLAT) as tobacco cigarettes substitute: a prospective 12-month randomized control design study. PLoS One 8:e66317

Bullen C, Howe C, Laugesen M, McRobbie H, Parag V, Williman J et al (2013) Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 382:1629–1637

Adriaens K, Van Gucht D, Declerck P, Baeyens F (2014) Effectiveness of the electronic cigarette: an 8-week Flemish study with 6-month follow-up on smoking reduction, craving and experienced benefits and complaints. Int J Environ Res Public Health 11:11220–11248

Halpern SD, Harhay MO, Saulsgiver K, Brophy C, Troxel AB, Volpp KG (2018) A pragmatic trial of e-cigarettes, incentives, and drugs for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med 378(24):2302–2310. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1715757

Borderud SP, Li Y, Burkhalter JE, Sheffer CE, Ostroff JS (2014) Electronic cigarette use among patients with cancer: characteristics of electronic cigarette users and their smoking cessation outcomes. Cancer 120(22):3527–3535. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28811(Epub 2014 Sep 22)

Brose LS, Hitchman SC, Brown J, West R, McNeill A (2015) Is the use of electronic cigarettes while smoking associated with smoking cessation attempts, cessation and reduced cigarette consumption? A survey with a 1-year follow-up. Addiction 110:1160–1168

Manzoli L, Flacco ME, Fiore M, La Vecchia C, Marzuillo C, Gualano MR, Liguori G, Cicolini G, Capasso L, D’Amario C, Boccia S, Siliquini R, Ricciardi W, Villari P (2015) Electronic cigarettes efficacy and safety at 12 months: cohort study. PLoS One 10(6):e0129443. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0129443(eCollection 2015)

Villanti AC, Feirman SP, Niaura RS, Pearson JL, Glasser AM, Collins LK, Abrams DB (2018) How do we determine the impact of e-cigarettes on cigarette smoking cessation or reduction? Review and recommendations for answering the research question with scientific rigor. Addiction 113:391–404

Farsalinos KE, Stimson GV (2014) Is there any legal and scientific basis for classifying electronic cigarettes as medications? Int J Drug Policy 25(3):340–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.03.003

European Commission (2017) Eurobarometer 458. Attitudes of Europeans towards tobacco and electronic cigarettes. https://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/ResultDoc/download/DocumentKy/79002. Accessed 9 Oct 2018

Farsalinos KE, Siakas G, Poulas K, Voudris V, Merakou K, Barbouni A (2018) Electronic cigarette use in Greece: an analysis of a representative population sample in Attica prefecture. Harm Reduct J 15(1):20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-018-0229-7

Filippidis FT (2016) Tobacco control: a victim of political instability in Greece. Lancet 387:338–339

Joossens L, Raw M (2016) The Tobacco Control Scale 2016 in Europe. https://www.tobaccocontrolscale.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/TCS-2016-in-Europe-COMPLETE-LoRes.pdf. Accessed 30 Nov 2018

Delnevo CD, Giovenco DP, Steinberg MB, Villanti AC, Pearson JL, Niaura RS, Abrams DB (2016) Patterns of electronic cigarette use among adults in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res 18(5):715–719. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntv237

Farsalinos KE, Spyrou A, Tsimopoulou K, Stefopoulos C, Romagna G, Voudris V (2014) Nicotine absorption from electronic cigarette use: comparison between first and new-generation devices. Sci Rep 26(4):4133

Kulik MC, Lisha NE, Glantz SA (2018) E-cigarettes associated with depressed smoking Cessation: a cross-sectional study of 28 European Union Countries. Am J Prev Med 54:603–609

Amato MS, Boyle RG, Levy D (2016) How to define e-cigarette prevalence? Finding clues in the use frequency distribution. Tob Control 25:e24–e29

Levy DT, Yuan Z, Luo Y, Abrams DB (2017) The relationship of e-cigarette use to cigarette quit attempts and cessation: insights from a large, nationally representative US Survey. Nicotine Tob Res. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntx166

Farsalinos KE, Poulas K, Voudris V, Le Houezec J (2017) Prevalence and correlates of current daily use of electronic cigarettes in the European Union: analysis of the 2014 Eurobarometer survey. Intern Emerg Med 12:757–763

Hartwell G, Thomas S, Egan M, Gilmore A, Petticrew M (2017) E-cigarettes and equity: a systematic review of differences in awareness and use between sociodemographic groups. Tob Control 26:e85–e91

Piñeiro B, Correa JB, Simmons VN, Harrell PT, Menzie NS, Unrod M, Meltzer LR, Brandon TH (2016) Gender differences in use and expectancies of e-cigarettes: online survey results. Addict Behav 52:91–97

Friedman AS, Horn SJL (2018) Socioeconomic disparities in electronic cigarette use and transitions from smoking. Nicotine Tob Res. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/nty120

Giovenco DP, Lewis MJ, Delnevo CD (2014) Factors associated with E-cigarette use: a national population survey of current and former smokers. Am J Prev Med 47:476–480

Farsalinos KE, Poulas K, Voudris V, Le Houezec J (2016) Electronic cigarette use in the European Union: analysis of a representative sample of 27,460 Europeans from 28 countries. Addiction 111:2032–2040

Adkison SE, O’Connor RJ, Bansal-Travers M et al (2013) Electronic nicotine delivery systems: international tobacco control four-country survey. Am J Prev Med 44:207–215

King BA, Patel R, Nguyen KH, Dube SR (2015) Trends in awareness and use of electronic cigarettes among US adults, 2010–2013. Nicotine Tob Res 17:219–227

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors report no conflicts of interest for the past 36 months.

Statement of human and animal rights

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Onassis Cardiac Surgery Center (reference nr: 591/14.12.16).

Informed consent

All participants provided verbal informed consent at the beginning of the telephone interview before participating to the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection: Health Impact of Electronic Cigarettes and Tobacco Heating Systems.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Farsalinos, K., Siakas, G., Poulas, K. et al. E-cigarette use is strongly associated with recent smoking cessation: an analysis of a representative population sample in Greece. Intern Emerg Med 14, 835–842 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-018-02023-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-018-02023-x