Abstract

We aim to compare complications, readmission, survival, and prescribing patterns of opioids for post-operative pain management for Robotic-assisted laparoscopic radical cystectomy (RARC) as compared to open radical cystectomy (ORC). Patients that underwent RARC or ORC for bladder cancer at a tertiary care center from 2005 to 2021 were included. Recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) were evaluated with Kaplan–Meier curves and multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models. Comparisons of narcotic usage were completed with oral morphine equivalents (OMEQ). Multivariable linear regression was used to assess predictors of OMEQ utilization. A total of 128 RARC and 461 ORC patients were included. There was no difference in rates of Clavien-Dindo grade ≥ 3 complications between RARC and ORC (36.7 vs 30.1%, p = 0.16). After a mean follow up of 3.4 years, RFS (HR 0.96, 95%CI 0.58–1.56) and OS (HR 0.69, 95%CI 0.46–1.05) were comparable between RARC and ORC. There was no difference in the narcotic usage between patients in the RARC and ORC groups during the last 24 h of hospitalization (median OMEQ: 0 vs 0, p = 0.33) and upon discharge (median OMEQ: 178 vs 210, p = 0.36). Predictors of higher OMEQ discharge prescriptions included younger age [(− )3.46, 95%CI (−)5.5–(−)0.34], no epidural during hospitalization [− 95.85, 95%CI (− )144.95−(− )107.36], and early time-period of surgery [(− )151.04, 95%CI (− )194.72–(− )107.36]. RARC has comparable 90-day complication rates and early survival outcomes to ORC and remains a viable option for bladder cancer. RARC results in comparable levels of opioid utilization for pain management as ORC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Radical cystectomy (RC) with or without neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) is the standard of care in management of muscle-invasive and aggressive non-muscle invasive bladder cancer [1]. Robotic-assisted radical cystectomy (RARC) has become an increasingly utilized alternative approach to open radical cystectomy (ORC) in recent years [2]. Data suggests RARC is a safe and comparable option to ORC for cancer control with improvements in perioperative outcomes, such as estimated blood loss (EBL), reduced length of stay (LOS) in the hospital, decreased incidence of ileus, and lower blood transfusion rates [3,4,5]. However, recent multicenter studies comparing RARC versus ORC have shown comparable post-operative quality of life, morbidity, complication rates, mortality rates, and oncological outcomes [2, 6]. Additional studies have not shown a significant difference in recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) between RARC and ORC patients in the early follow-up period [7].

Specifically, the RAZOR trial, which randomized patients to RARC or ORC, demonstrated non-inferiority of RARC to ORC in progression-free survival at 2 years [6]. Updated analysis at 3 years again demonstrated equivalent outcomes [8]. Furthermore, the RAZOR trial was consistent with previous findings of decreased EBL and shorter LOS with RARC. In recent years, efforts have been made to further improve postoperative outcomes for cystectomies through Enhanced Recovery after Surgery (ERAS) protocols which include reduction in opioid usage [7]. However, few studies have quantified changes over time in opioid use prior to discharge, opioid prescribing, and perioperative outcomes after RC with greater awareness of the impact of postoperative opioid use and implementation of ERAS. Therefore, the present study aims to evaluate comparative perioperative, opioid, and survival outcomes for RARC and ORC and assess for changes over time in a contemporary cohort.

Material and methods

Given its retrospective nature, this project was exempted by the Institutional Review board from review. Patients ≥ 18 years of age who underwent RC for bladder cancer at a single institution, Loyola University Medical Center, were retrospectively identified from 2005 to 2021 via operative logs. Patients undergoing cystectomy for reasons other than primary bladder cancer were excluded, such as gynecologic malignancy, colorectal malignancy, or for benign indications. Patient demographics, comorbidities, management, preoperative and postoperative staging, perioperative data, and postoperative outcomes were extracted and stored in a HIPPA compliant REDCap database. Major comorbidities were defined as diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease (CAD), cerebrovascular disease (CVA), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and liver disease. Opioid usage was calculated for the last 24 h of inpatient admission using the sum of oral morphine equivalents (OMEQ) across medications. Given the known association of opioid use prior to discharge with post-discharge utilization, the last 24 h was selected to reflect a similar window for patients [9]. OMEQ of discharge prescriptions were recorded. Complications were recorded according to the Clavien-Dindo classification. Major complications were Clavien-Dindo grade 3 or above.

Descriptive statistics were performed. Baseline demographics, comorbidities, cancer stage, treatments, and outcomes were compared between patients receiving RARC and ORC. Perioperative outcomes included EBL, operative time, LOS, rates of aborted surgery, 90-day complication rates, and readmission rates. Opioid outcomes included inpatient OMEQ use in the 24 h prior to discharge and discharge prescription OMEQ. A stratified analysis was performed of perioperative and opioid outcomes in early and late time periods. Early and late periods were defined based on the median RARC procedure date (August 2016). The late period also coincided with greater utilization of ERAS. Univariable and multivariable linear regression analysis was used to identify risk factors for higher inpatient opioid use and discharge opioid OMEQ amounts.

Survival outcomes included OS and RFS of patients receiving RARC and ORC. OS was evaluated by multivariable cox proportional hazards regression models and Kaplan Meier curves. RFS of patients receiving RARC and ORC was calculated in a similar fashion. Survival analyses focused on patients with primary urothelial carcinoma with a sub-analysis among patients with muscle-invasive disease (≥ cT2).

Results

A total of 128 RARC and 461 ORC patients were eligible for inclusion. The mean follow up was 3.4 years. Table 1 depicts baseline characteristics of RARC and ORC patients. There were notable differences among the two groups. Patients undergoing RARC were more likely to have CAD (35.2 vs 22.1%, p = 0.003) and prior CVA (12.5 vs 5.0%, p = 0.002). Patients undergoing ORC were more likely to have chronic kidney disease (32.3 vs 14.1%, p < 0.001), prior abdominal surgeries (48.2% vs 38.3%, p = 0.05), and receive a continent diversion (34.5 vs 13.3%, p < 0.001) (Table 1, Online Resource 1). Clinical and pathologic staging and NAC utilization was similar between groups. However, patients undergoing ORC were more likely to have variant histology (27.1 vs 13.3%, p = 0.008). A total of 22 (17.2%) RARC patients received an intracorporeal urinary diversion (ICUD) while the remainder were extracorporeal urinary diversions (ECUD).

In the overall cohort, RARC was associated with longer operative time (450 vs 396 min, p < 0.001), less blood loss (200 vs 800 cc, p < 0.001), and shorter LOS (6 vs 9 days, p < 0.001) (Online Resource 1). A total of 3/128 (2.3%) of RARC cases were aborted during surgery due to inability to tolerate insufflation or bladder fixation, while 3/461 (0.7%) of ORC cases were aborted due to abdominal metastatic disease. Overall, rates of major complications (Clavien-Dindo grade ≥ 3) were similar between RARC and ORC (36.7 vs 30.1%, p = 0.16).

There were notable differences in outcomes between the early and recent RC cohorts (Table 2). While the operative time was significantly shorter for ORC, as compared to RARC, in both early (410 vs 480 min, p < 0.001) and recent cohorts (369 vs 420 min, p < 0.001), operative time in the recent cohort decreased (p < 0.001) by a median of 41 and 60 min for ORC and RARC, respectively. LOS decreased by a mean of 2.1 days (p = 0.03) and 3.0 days (p = 0.02) in the recent cohort for ORC and RARC, respectfully (mean 2.8 for overall cohort). However, the LOS was shorter for RARC in both early (7 vs 10 days, p = 0.01) and recent (6 vs 7 days, p = 0.004) cohorts. There was no difference in EBL or readmissions between the early and late cohorts.

There were significantly more patients with major complications (Clavien-Dindo grade ≥ 3) in the early RARC cohort compared to the recent RARC cohort (46.0 vs 27.7%, p = 0.03). However, there was no difference in the number of patients with major complications in the early ORC cohort compared to the recent ORC (31.4 vs 27.6%, p = 0.41). In addition, there were more major complications in the early RARC cohort compared to the early ORC cohorts, while major complication rates in the recent cohorts were similar (Table 2). The most common major complications were GI, renal, infectious and pulmonary in both the early and recent cohorts. Online Resource 2 depicts complication rates for ORC and RARC in the early and recent time periods. Online Resource 3 stratifies the analysis based on type of diversion for complications, EBL, LOS, operative time, and readmission rate.

There was no difference in opioid use between ORC and RARC in the last 24 h of admission (mean 12.1 vs. 10.0, respectively; median 0 vs. 0, respectively; p = 0.33) nor opioids prescribed at discharge (median 210 vs. 178, respectively; p = 0.36) (Table 3). Older age and epidural use were significant predictors of reduced inpatient OMEQ in the last 24 h and reduced OMEQ prescribed at discharge (Online Resource 4). Importantly, greater inpatient OMEQ used in the last 24 h correlated with greater discharge prescription OMEQ (median 165 OMEQ if 0 inpatient OMEQ, 200 OMEQ if 1–15 inpatient OMEQ, and 300 OMEQ if > 15 inpatient OMEQ). There was no difference in inpatient opioid use in the last 24 h between the early and late cohorts (mean 12.0 vs. 11.0, respectively; median 0 vs. 0, respectively; p = 0.59). However, there was reduced mean discharge opioid prescribing in the late cohort for all patients (305 OMEQ vs 184 OMEQ, p < 0.001), ORC (297 OMEQ vs 201 OMEQ, p < 0.001), and RARC (348 OMEQ vs 145 OMEQ, p < 0.001).

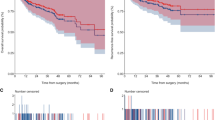

RFS (HR 0.96 (95%CI 0.58–1.56), p = 0.86) and OS (HR 0.69 (95%CI 0.46–1.05), p = 0.08) were similar between ORC and RARC (Figs. 1, 2). Patients with non-muscle invasive bladder cancer and variant histology were excluded. After a mean follow up of 3.2 years, recurrence-free survival (HR 0.96, 95%CI 0.58–1.56, p = 0.86) and overall survival (HR 0.69, 95%CI 0.46–1.05, p = 0.08) were comparable in adjusted multivariable Cox models between RARC and ORC for patients with primary muscle invasive pure urothelial carcinoma. The presence of major comorbidities (HR 1.62, 95% CI 1.16–2.27, p = 0.005) and older age (HR 1.04, 95% CI 1.02–1.06, p < 0.001) were associated with worse OS (Online Resource 5). Higher pT stage (i.e., pT4 HR 9.04, 95% CI 3.63–22.55, p < 0.001) and pN stage (i.e., pN3 HR 2.92, 95% CI 1.47–5.77, p = 0.002) were associated with both worse RFS and OS. Findings were similar in the subset with muscle-invasive disease, although significant findings were limited to pT and pN stage (Online Resource 5).

Discussion

Given the increased utilization and experience in performing RARC over time, comparing perioperative and oncologic outcomes to patients receiving ORC remains important with periodic re-evaluation. Greater awareness of the risks of opioid use and broader implementation of ERAS has also impacted the landscape of outcomes after RC. In the present study, we demonstrate improved perioperative outcomes over time for both RARC and ORC with EBL and LOS favoring RARC; however, major complication rates and readmission rates were no different in recent years between the two surgical approaches. Importantly, post-discharge opioid has decreased by over 40% with minimal differences in inpatient opioid use prior to discharge and opioid prescribing between RARC and ORC. The RAZOR trial demonstrated RARC is non-inferior to ORC for 2-year progression free-survival, which remained true on updated analysis at 3 years [6, 8]. In the present study, with 3.2 years mean follow-up, the RFS and OS between RARC and ORC patients with primary muscle invasive pure urothelial carcinoma were comparable as well. Patients with variant histology were intentionally excluded from this analysis, given the unequal distribution of variant histology between approaches and the known association of variant histology with worse long term oncologic outcomes, to avoid potential confounding despite adjusted analysis.

Previous multicenter studies demonstrated equivalent post-operative quality of life, morbidity, overall complication rates, mortality rates, and oncological outcomes between ORC and RARC [2, 10]. Additionally, initial small series reports suggest that RARC may result in lower post-operative opioid requirements, through this has not been consistently demonstrated [11, 12]. In our cohort, a robotic vs. open approach did not seem to substantially influence post-operative opioid utilization near time of discharge. Due to variation in post-operative pain management over time (regional and epidural blocks) and differences in length of stay as a result of ERAS and surgical approach, total opioid utilization throughout the inpatient hospitalization was not compared. While one study found a dedicated effort to reduce opioid prescribing at discharge for RC could omit a prescription in 70% of cases, our data likely reflect a more gradual change in practice patterns due to increased awareness as well as ERAS efforts which could be improved upon with dedicated interventions in the future [12].

The overall major complication (Clavien-Dindo grade ≥ 3) rate of 31.5% is consistent with the literature and these rates were similar between ORC and RARC in our cohort. Interestingly, there were differences in major complication rates in RARC, but not ORC, when patients were separated into early and late cohorts. There were significantly fewer major complications in the late RARC cohort compared to the early RARC cohort. While there were significantly fewer fascial, wound, and stomal complications in the late RARC cohort, the overall improvement of major complications can be attributed to a trend of slight reduction across most categories. While adoption of ERAS pathways may have contributed to the improvement of complication rates in the late cohort, the isolated significant improvement in the late RARC cohort implies additional influencing factors. The improvements in RARC complications may be due to increased utilization and experience. Lomardo et al. previously evaluated the learning curve of RARC and found that 20 cases were required to reach a plateau in operative time and 60 cases to achieve a plateau in complication rates [13]. Presumably, once the learning curve is achieved, complications rates are comparable to ORC. Notably, the average operative time decreased by one hour from the early to late RARC cohorts.

The Enhanced Recovery after Surgery (ERAS) model of care was developed for use in colorectal surgery in 1997 to reduce postoperative recovery time and decrease postoperative complications [14]. These protocols have since been adapted and expanded for urology use in the RC population [7, 14]. Improvements in LOS were appreciated for all cystectomies in the late cohort compared to early with mean reduction of 2.8 days. There was a 6.2% overall improvement in major complication rates over time although the primary benefit was for RARC cases. Our findings are consistent with previous reports that demonstrate the main benefit of ERAS protocols in RC is a reduction in LOS with potentially less impact on postoperative complications and readmissions [14].

Reduction in opioid usage during postoperative hospitalization through ERAS programs has been shown to improve postoperative outcomes for RC [7]. When opioid usage was minimized postoperatively, the majority of cystectomy patients halved their LOS in one cohort [15]. There is limited data on opioid utilization when comparing to ORC to RARC, and current small cohort studies show conflicting results [11, 12]. We found that during the last 24 h of inpatient hospitalization, where inpatient use is associated with post-discharge use, there was not a significant difference between RARC and ORC patients [9].

There was also no difference in OMEQ of discharge prescriptions given to patients between the ORC and RARC cohorts. We found that predictors of lower OMEQ discharge prescriptions included lower inpatient OMEQ used in the last 24 h, older age, epidural use during hospitalization, and RC performed in the recent time-period. The rise of the opioid epidemic, national efforts to reduce opioid prescriptions in the last decade, and ERAS considerations are likely responsible for decreased OMEQ discharge prescriptions in the recent cystectomy cohort. Opioid deescalating ERAS protocols that include multimodal pain control, such as epidural use, are paramount. Our findings are consistent with previous studies where implementation of a non-opioid protocol (NOP) post-RARC was associated with reduced need for post-operative opioid analgesia and prescriptions at discharge with no significant influence on complications or readmission rates [16]. There is likely room for adjusting dosages such that patients using minimal narcotics (< 15 OMEQ) in the last 24 h of hospitalization may be sent home with lower OMEQ dosages or non-opioid medications alone based on the 70% benchmark recently achieved in one cohort [12].

There are two main limitations to acknowledge in this retrospective study. First, inpatient opioid utilization was calculated for the last 24 h. As ORC was associated with a longer LOS by 2 days, this may confound the findings slightly although mean use was only ~ 12 OMEQ at this timepoint. Nevertheless, this cohort represents a real-world experience and emphasizes the importance of multimodal pain management to reduce both inpatient and post-discharge opioid usage. Furthermore, discharge opioid prescriptions should be tailored to the patient’s needs. Second, our cohort does not include a significant number of RARC with ICUD. With methods such as vaginal extraction in female RARC patients, ICUD can avoid larger incisions necessary for ECUD and thus possibly reduce post-operative pain and opioid use. Furthermore, there is emerging evidence that RARC with ICUD may improve perioperative and post-operative outcomes compared to ORC and/or RARC with ECUD [4, 17,18,19]. As RARC utilization has increased substantially, we expect an associated rise in the proportion of patients receiving ICUD which should allow for further evaluation.

Conclusions

RARC has comparable 90-day complication rates, readmission rates, and early survival outcomes but less EBL and shorter LOS relative to ORC. The amount of opioids for pain management utilized during the last 24 h of hospitalization and prescriptions upon discharge were similar by surgical approach with significant reductions in prescribing by > 40% in more recent years. The morbidity of RC remains significant but with notable improvements in LOS and major complications rates in more recent years reflecting improvements due to ERAS implementation and surgeon experience.

Data availability statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information.

References

Wu J, Xie RY, Cao CZ, Shang BQ, Shi HZ, Shou JZ (2022) Disease management of clinical complete responders to neoadjuvant chemotherapy of muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a review of literature. Front Oncol 12:816444. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.816444

Hussein AA, Li Q, Guru KA (2022) Robot-assisted radical cystectomy: surgical technique, perioperative and oncologic outcomes. Curr Opin Urol 32(1):116–122. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOU.0000000000000953

Smith AB, Raynor M, Amling CL et al (2012) Multi-institutional analysis of robotic radical cystectomy for bladder cancer: perioperative outcomes and complications in 227 patients. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech 22(1):17–21. https://doi.org/10.1089/lap.2011.0326

Mortezavi A, Crippa A, Kotopouli MI, Akre O, Wiklund P, Hosseini A (2022) Association of open vs robot-assisted radical cystectomy with mortality and perioperative outcomes among patients with bladder cancer in Sweden. JAMA Netw Open 5(4):e228959. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.8959

Moschovas MC, Seetharam Bhat KR, Jenson C, Patel VR, Ogaya-Pinies G (2021) Robtic-assisted radical cystectomy: literature review. Asian J Urol 8(1):14–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajur.2020.06.007

Parekh DJ, Reis IM, Castle EP et al (2018) Robot-assisted radical cystectomy versus open radical cystectomy in patients with bladder cancer (RAZOR): an open-label, randomised, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 391(10139):2525–2536. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30996-6

Azhar RA, Bochner B, Catto J et al (2016) Enhanced recovery after urological surgery: a contemporary systematic review of outcomes, key elements, and research needs. Eur Urol 70(1):176–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2016.02.051

Venkatramani V, Reis IM, Castle EP et al (2020) Predictors of recurrence, and progression-free and overall survival following open versus robotic radical cystectomy: analysis from the RAZOR trial with a 3-year followup. J Urol 203(3):522–529. https://doi.org/10.1097/JU.0000000000000565

Su ZT, Becker RE, Huang MM et al (2022) Patient and in-hospital predictors of post-discharge opioid utilization: individualizing prescribing after radical prostatectomy based on the ORIOLES initiative. Urol Oncol 40(3):104.e9-104.e15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2021.10.007

Wijburg CJ, Michels CTJ, Hannink G et al (2021) Robot-assisted radical cystectomy versus open radical cystectomy in bladder cancer patients: a multicentre comparative effectiveness study. Eur Urol 79(5):609–618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2020.12.023

Maibom SL, Roder MA, Aasvang EK et al (2022) Open vs robot-assisted radical cystectomy (BORARC): a double-blinded, randomised feasibility study. BJU Int 130(1):102–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.15619

Myrga JM, Wu S, Gul ZG et al (2022) Discharge opioids are unnecessary following radical cystectomy. Urology 170:91–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2022.08.025

Lombardo R, Mastroianni R, Tuderti G et al (2021) Benchmarking PASADENA consensus along the learning curve of robotic radical cystectomy with intracorporeal neobladder: CUSUM based assessment. J Clin Med 10(24):5969. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10245969

Semerjian A, Milbar N, Kates M et al (2018) Hospital charges and length of stay following radical cystectomy in the enhanced recovery after surgery era. Urology 111:86–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2017.09.010

Abaza R, Kogan P, Martinez O (2022) Narcotic avoidance after robotic radical cystectomy allows routine of only two-day hospital stay. Urology 161:65–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2021.10.049

Pfail JL, Garden EB, Gul Z et al (2021) Implementation of a nonopioid protocol following robot-assisted radical cystectomy with intracorporeal urinary diversion. Urol Oncol 39(7):436 e9-436 e16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2021.01.002

Tan YG, Allen JC, Tay KJ, Huang HH, Lee LS (2020) Benefits of robotic cystectomy compared with open cystectomy in an Enhanced Recovery After Surgery program: a propensity-matched analysis. Int J Urol 27(9):783–788. https://doi.org/10.1111/iju.14300

Catto JWF, Khetrapal P, Ricciardi F et al (2022) Effect of robot-assisted radical cystectomy with intracorporeal urinary diversion vs open radical cystectomy on 90-day morbidity and mortality among patients with bladder cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 327:2092. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.7393

Mastroianni R, Ferriero M, Tuderti G et al (2022) Open radical cystectomy versus robot-assisted radical cystectomy with intracorporeal urinary diversion: early outcomes of a single-center randomized controlled trial. J Urol 207(5):982–992. https://doi.org/10.1097/JU.0000000000002422

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

No funds, grants, or other support was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Protocol/project development: HP, GR, GP, GG, MW, AG, MQ. Data collection or management: RY, HP, GR, MF, GP, CK, YO, UN, VC, AD. Data analysis: HP, GR, MF. Manuscript writing/editing: RY, HP, GR, MF, GG, MW, AG, MQ. Protocol/project development: HP, GR, GP, GG, MW, AG, MQ. Data collection or management: RY, HP, GR, MF, GP, CK, YO, UN, VC, AD. Data analysis: HP, GR, MF. Manuscript writing/editing: RY, HP, GR, MF, GG, MW, AG, MQ.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical approval

Given its retrospective nature, this project was exempted by the Institutional Review board from review.

Consent to Participate

Given its retrospective nature, this project was exempted by the Institutional Review board from needing consent to participate.

Consent to Publish

Given its retrospective nature, this project was exempted by the Institutional Review board from needing consent to publish.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, R., Rac, G., Felice, M.D. et al. Robotic versus open radical cystectomy for bladder cancer: evaluation of complications, survival, and opioid prescribing patterns. J Robotic Surg 18, 10 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11701-023-01749-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11701-023-01749-x