Abstract

Robotic surgical technology has grown in popularity and applicability, since its conception with emerging uses in general surgery. The robot’s contribution of increased stability and dexterity may be beneficial in technically challenging surgeries, namely, inguinal hernia repair. The aim of this project is to contribute to the growing body of literature on robotic technology for inguinal hernia repair (RIHR) by sharing our experience with RIHR at a large, academic institution. We performed a retrospective chart review spanning from March 2015 to April 2018 on all patients who had undergone RIHR at our university hospital. Extracted data include preoperative demographics, operative features, and postoperative outcomes. Data were analyzed with particular focus on complications, including hernia recurrence. A total of 43 patients were included, 40 of which were male. Mean patient age was 56 (range 18–85 years) and mean patient BMI was 26.4 (range 17.5–42.3). Bilateral hernias were diagnosed in 13 patients. All of the patients received transabdominal approaches, and all but one received placement of synthetic polypropylene mesh. There was variety in mesh placement with 23 patients receiving suture fixation and 14 receiving tack fixation. Several patients received a combination of suture, tacks, and surgical glue. Mean patient in-room time was 4.0 h, mean operative time was 2.9 h, and mean robotic dock time was 2.0 h. Regarding intraoperative complications, there was one bladder injury, which was discovered intraoperatively and repaired primarily. Same-day discharges were achieved in 32 patients (74.4%) of patients. One patient was admitted overnight for management of urinary retention. Additional ten patients were admitted for observation. Post-operatively, none of the cases resulted in wound infections. Eleven patients developed seromas and one patient was diagnosed with a groin hematoma. Median follow-up was 37.5 days, and one recurrence was reported during this time. The recurrent hernia in this case was initially discovered during a separate case and was repaired with temporary mesh. The use of the robot is safe and effective and should be considered an acceptable approach to inguinal hernia repair. Future prospective studies will help define which patients will benefit most from this technology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

With the lifetime risk of inguinal hernia nearly 30% for men and 3% for women, inguinal hernia repair is one of the most frequently performed general surgery operations [1]. Since its application to hernioplasty, laparoscopy has offered several advantages over the open approach, including an earlier return to activity and a lower incidence of wound infection, hematoma, and chronic postoperative pain and numbness [2]. The da Vinci (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) robot provides minimally invasive surgeons with a versatile instrument to expand their skills beyond the traditional laparoscopy. Given the limited working space in the pelvis and the increased dexterity and visualization offered by the robot, there is a potential advantage in using the robot for inguinal hernia repair.

Initial reports of this procedure were from those performed with concomitant urological surgeries. These studies demonstrated the safety of reducing inguinal hernias with the da Vinci robot after it had already been docked and utilized for another pelvic surgery [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. Since then, several other institutions have studied the outcomes of robotically assisted hernia repair as a standalone procedure and have found it to be a safe and effective option [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. A study out of Belgium found that the robot may even offer certain advantages over laparoscopy, including a reduction in the operative time during the learning curve of the procedure [23]. We aimed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of robotically assisted transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) inguinal hernia repair over a 3-year period at a large, academic institution.

Materials and methods

Data collection and analysis

This study is a retrospective review of all patients who had undergone robotic inguinal hernia repair from March 2015 to April 2018. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained prior to initiation of this study. Patients were initially identified based on Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes and then manually sorted to identify robotic hernia repairs. The REDcap electronic data capture tools were used [24]. Ninety-four data points were collected for each patient including: preoperative history, risk factors, and demographics; perioperative details and time spent in OR; and postoperative complications. Data were analyzed using RStudio (Version 1.1.456 © 2009–2018 RStudio, Inc.) statistical software.

Surgical method

All surgeries took place at either the Keck Medical Center or Verdugo Hills Hospital, both of which are University of Southern California affiliates, using either a da Vinci Xi or Si robotic system, and performed by one of seven surgeons. All hernias were performed through a TAPP approach, requiring the use of three trocars. Following dissection and reduction of the hernia sac, fixation of a synthetic polypropylene mesh with glue, tacks, sutures, or a combination of these materials was performed at the discretion of the surgeon. Following the undocking of the robot, the incisions were closed primarily, and the patient was either discharged home or admitted for observation.

Results

Preoperative demographics

During the study period, a total of 276 hernia repairs were performed, of which 145 were repaired laparoscopically, 88 open, and 43 robotically. Of the 43 patients who received a robotic hernioplasty, 40 were male. The patients had a mean age of 56 years (range 18–85 years). Twelve of the patients had bilateral hernias confirmed during surgery, which led to a total of 55 hernias repaired. During one planned bilateral inguinal hernia repair, one side was not repaired due to a difficult repair on the other side involving a large hernia sac and eventual orchiopexy. In total, 54 hernias were repaired robotically (27 left and 27 right).

For the left-sided hernias, seven were described as small, four as medium, and three as large. For the right-sided hernias, twelve were characterized as small, five as medium, and four as large. Seventeen patients reported having their hernia(s) for fewer than 6 months, five reported 6–12 months, eleven reported one to 5 years, two reported 6 to 10 years, and three reported having their hernia greater than 10 years. Thirty-eight hernias were described as “reducible” and two were incarcerated. Five of the left-sided only hernias, three of the right-sided only hernias, and two of the bilateral hernias were recurrent (Table 1).

One patient reported a family history of inguinal hernias, ten had undergone a previous hernia repair, and eleven had a history of a prior abdominal surgery. Sixteen patients had a history of hypertension, three had diabetes, three had frequent constipation, one had COPD, and one had asthma. Eleven patients reported a smoking history. The mean patient BMI was 26.4 (range 17.5–42.3) (Table 2).

Intraoperative characteristics

For the left-sided hernias, seventeen were indirect, seven were direct, three were femoral, and one patient had no peritoneal defect. For the right-sided hernias, fourteen were indirect, twelve were direct, three were femoral, and one patient had no peritoneal defect. Two patients had laparoscopic fixation of the mesh following robotic dissection, reduction of the hernia sac, and placement of the mesh. All of the operations were performed transabdominally and all but one included formal fixation of synthetic polypropylene mesh. Twenty-six of surgeries were performed with Bard 3Dmax mesh, seven with Prolene soft mesh, six with Bard 3Dmax light mesh, two with Ethicon mesh, one with Phasix mesh, and one with Covidien Progrip mesh. Regarding mesh fixation, 23 patients had suture only, 14 had tacks only, one had a combination of suture and tacks, two had suture and glue, and two had tacks and glue.

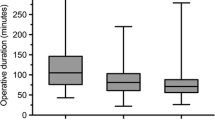

The mean patient in-room time was 4.0 h (range 2.2–7.2 h), mean operative time was 2.9 h (range 31 min–5.9 h), and the mean time the robot was docked was 2.0 h (range 1.0–5.0 h). Of note, ten of these patients had another procedure performed during their inguinal hernia repair. Six of these were concomitant with a urological procedure, three included the repair of a ventral or umbilical hernia, one required lysis of adhesions in addition to a ventral hernia repair, and one underwent an EGD following his hernia repair. Additionally, residents performed different aspects of each case depending on their year and skill level, which likely contributed to lengthened and variable operative times.

Excluding these patients, the average operative times become: in-room 3.6 (range 2.2–5.3) h; operative time 2.5 (31 min–4.0) h; and robot docked 1.6 (range 1.0–3.0) h. Of these hernia-only surgeries, eight were bilateral repairs. The average operative times for the bilateral, hernia-repair only patients were: in-room 4.3 (range 3.2–5.3) h; operative time 3.2 (range 2.1–4.0) h; and robot docked 2.2 (range 1.3–3.0) h. The average operative times for the unilateral, hernia-repair only patients were: in-room 3.4 (range 2.2–4.5) h; operative time 2.3 (31 min–3.7) h; and robot docked 1.5 (range 1.0–2.7) h. Thirty-one patients were discharged on the day of surgery. One patient was observed overnight for treatment of urinary retention. The other ten patients were kept for one or two nights. One was for severe postoperative pain, one was for monitoring following intraoperative bladder repair, two were for patients with significant medical comorbidities, and seven were for monitoring after multiple, concomitant procedures (Table 3).

Postoperative outcomes

Post-operatively, none of the patients developed wound infections, one had urinary retention, 11 developed seromas, and one patient had a groin hematoma. By the third follow-up appointment, an average of 113 days postop, the hematoma and all of the seromas had resolved. At a median follow-up of 37.5 days, there was one recurrence (Table 4). This hernia was discovered incidentally during a urological procedure and was repaired at that time using the robot with a temporary, absorbable Vicryl mesh to prevent immediate postoperative incarceration or infection. The patient’s hernia recurred 5 months after this temporary repair, but because he was asymptomatic and concerned about the risks of surgery, he elected to manage the hernia nonoperatively.

Discussion

Our results support the growing body of literature demonstrating the safety and efficacy of robotic inguinal hernia repair [22, 25]. Given the diversity of hernia laterality, size, and defect type, our data show that robotic technology can be applied to a wide variety of cases. Our patients also had a range of comorbidities, with hypertension most frequently reported. Over half of the patients in this study had BMIs in the overweight or obese categories, supporting the previous work that robotic surgery is a safe option for patients with higher BMIs [17] as well as patients with medical comorbidities [16]. Due to this, we have concluded that a robotically assisted approach to inguinal hernia repair should be considered as a surgical option for unilateral and bilateral cases, including patients with high BMIs and other comorbidities.

There is also some evidence to suggest that using the robot is not just equivalent to laparoscopy; it may actually offer certain advantages over the traditional laparoscopy. Data by Kudsi et al. suggest the robot may actually allow surgeons to complete more complex cases with similar operative times and complication rates compared to less complex laparoscopic cases [18]. Iraniha et al. found that these low rates of complication and improved quality of life persist long-term following robotic hernia repair [12]. A robotic approach may also lead to less postoperative pain [14, 21]. Gamagami et al. found that their robotic cases led to fewer postoperative complications following discharge [15], while the other studies found no statistical difference between robotic and laparoscopic surgical outcomes [19, 26].

Despite studies demonstrating better outcomes with a minimally invasive approach to inguinal hernia repair [2], the majority of general surgeons still choose an open approach [27]. This is likely due to the known steep learning curve of laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. With the more widespread adoption of robotic technology, data have emerged, suggesting that the robotic approach may be easier to learn [23]. In addition to the literature supporting the use of the robot in inguinal hernia repair, the ergonomic benefits of the da Vinci robot [28] could become a factor in encouraging more surgeons to pursue a minimally invasive approach. Improved ergonomics has the potential to reduce the demand on a surgeon’s body while also providing more patients with the advantages of minimally invasive surgery.

The da Vinci robot has been used successfully in large academic institutions such as ours, as well as at VA hospitals [14] and small community hospitals [20], leading to a wide range of applicability for this technology. A major concern for the implementation of the da Vinci robot has been cost. A recent cost analysis by Adelmoaty et al. found that using the robot led to significantly higher fixed costs but lower variable costs than laparoscopic cases and longer operative times [29]. Significant cost differences were also reported by Charles et al. [26], while other studies have reported no significant cost difference [21] and similar operative times between the two procedures [18, 23]. It also may be the case that while intraoperative costs and time are longer, patients spend less time in the hospital prior to discharge [21], reducing overall hospital stay costs. More data are necessary to appreciate the overall and long-term cost burden of the da Vinci robot on the healthcare system.

The limitations of this study are largely due to the retrospective design. These include: a lack of diversity in hernia complexity (only two hernias were incarcerated); it is not a comparative study between other approaches; and we were not able to make conclusions about postoperative pain. Additionally, given the average follow-up time of 37 days, this study was not able to comment on long-term hernia recurrence. Moving forward, our institution hopes to continue adding to this data set and implement a standardized way to quantify postoperative pain.

In conclusion, we believe that the robotic approach to inguinal hernia repair is safe and effective and should be considered a viable alternative to both laparoscopic and open repairs. Longer term studies will further define the role of this technology.

References

Primatesta P, Goldacre MJ (1996) Inguinal hernia repair: incidence of elective and emergency surgery, readmission and mortality. Int J Epidemiol 25(4):835–839

Cavazzola LT, Rosen MJ (2013) Laparoscopic versus open inguinal hernia repair. Surg Clin North Am 93(5):1269–1279

Atmaca AF, Hamidi N, Canda AE, Keske M, Ardicoglu A (2018) Concurrent repair of inguinal hernias with mesh application during transperitoneal robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy: is it safe. Urol J. 15(6):381–386

Rogers T, Parra-Davila E, Malcher F et al (2018) Robotic radical prostatectomy with concomitant repair of inguinal hernia: is it safe? J Robot Surg. 12(2):325–330

Lee DK, Montgomery DP, Porter JR (2013) Concurrent transperitoneal repair for incidentally detected inguinal hernias during robotically assisted radical prostatectomy. Urology. 82(6):1320–1322

Nakamura LY, Nunez RN, Castle EP, Andrews PE, Humphreys MR (2011) Different approaches to an inguinal hernia repair during a simultaneous robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. J Endourol 25(4):621–624

Collins JN, Britt RC, Britt LD (2011) Concomitant robotic repair of inguinal hernia with robotic prostatectomy. Am Surg 77(2):238–239

Kyle CC, Hong MK, Challacombe BJ, Costello AJ (2010) Outcomes after concurrent inguinal hernia repair and robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy. J Robot Surg. 4(4):217–220

Joshi AR, Spivak J, Rubach E, Goldberg G, DeNoto G (2010) Concurrent robotic trans-abdominal pre-peritoneal (TAP) herniorrhaphy during robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy. Int J Med Robot. 6(3):311–314

Finley DS, Savatta D, Rodriguez E, Kopelan A, Ahlering TE (2008) Transperitoneal robotic-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy and inguinal herniorrhaphy. J Robot Surg. 1(4):269–272

Finley DS, Rodriguez E, Ahlering TE (2007) Combined inguinal hernia repair with prosthetic mesh during transperitoneal robot assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: a 4-year experience. J Urol. 178(4 Pt 1):1296–1299 (discussion 1299–1300)

Iraniha A, Peloquin J (2018) Long-term quality of life and outcomes following robotic assisted TAPP inguinal hernia repair. J Robot Surg. 12(2):261–269

Yheulon CG, Maxwell DW, Balla FM et al (2018) Robotic-assisted laparoscopic repair of scrotal inguinal hernias. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 28(3):188–192

Kosturakis AK, LaRusso KE, Carroll ND, Nicholl MB (2018) First 100 consecutive robotic inguinal hernia repairs at a Veterans Affairs hospital. J Robot Surg. 12(4):699–704

Gamagami R, Dickens E, Gonzalez A et al (2018) Open versus robotic-assisted transabdominal preperitoneal (R-TAPP) inguinal hernia repair: a multicenter matched analysis of clinical outcomes. Hernia 22(5):827–836

Edelman DS (2017) Robotic Inguinal Hernia Repair. Am Surg 83(12):1418–1421

Kolachalam R, Dickens E, D’Amico L et al (2018) Early outcomes of robotic-assisted inguinal hernia repair in obese patients: a multi-institutional, retrospective study. Surg Endosc 32(1):229–235

Kudsi OY, McCarty JC, Paluvoi N, Mabardy AS (2017) Transition from laparoscopic totally extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repair to robotic transabdominal preperitoneal inguinal hernia repair: a retrospective review of a single surgeon’s experience. World J Surg 41(9):2251–2257

Arcerito M, Changchien E, Bernal O, Konkoly-Thege A, Moon J (2016) Robotic inguinal hernia repair: technique and early experience. Am Surg 82(10):1014–1017

Oviedo RJ, Robertson JC, Alrajhi S (2016) First 101 robotic general surgery cases in a Community Hospital. JSLS. https://doi.org/10.4293/JSLS.2016.00056

Waite KE, Herman MA, Doyle PJ (2016) Comparison of robotic versus laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) inguinal hernia repair. J Robot Surg. 10(3):239–244

Escobar Dominguez JE, Ramos MG, Seetharamaiah R, Donkor C, Rabaza J, Gonzalez A (2016) Feasibility of robotic inguinal hernia repair, a single-institution experience. Surg Endosc 30(9):4042–4048

Muysoms F, Van Cleven S, Kyle-Leinhase I, Ballecer C, Ramaswamy A (2018) Robotic-assisted laparoscopic groin hernia repair: observational case-control study on the operative time during the learning curve. Surg Endosc. 32(12):4850–4859

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG (2009) Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 42(2):377–381

Pirolla EH, Patriota GP, Pirolla FJC et al (2018) Inguinal repair via robotic assisted technique: literature review. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 31(4):e1408

Charles EJ, Mehaffey JH, Tache-Leon CA, Hallowell PT, Sawyer RG, Yang Z (2018) Inguinal hernia repair: is there a benefit to using the robot? Surg Endosc 32(4):2131–2136

Trevisonno M, Kaneva P, Watanabe Y et al (2015) A survey of general surgeons regarding laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair: practice patterns, barriers, and educational needs. Hernia 19(5):719–724

Lee GI, Lee MR, Clanton T, Sutton E, Park AE, Marohn MR (2014) Comparative assessment of physical and cognitive ergonomics associated with robotic and traditional laparoscopic surgeries. Surg Endosc 28(2):456–465

Abdelmoaty WF, Dunst CM, Neighorn C, Swanstrom LL, Hammill CW. Robotic-assisted versus laparoscopic unilateral inguinal hernia repair: a comprehensive cost analysis. Surg Endosc. 2018

Funding

No extra-institutional funding was obtained for this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Dr. Lipham consults for Torax Medical. Dr. Bildzukewicz consults for Torax Medical. Dr. Houghton consults for Torax Medical and Intuitive Medical. Marissa Maas and Drs. Alicuben, Samakar, Sandhu, Dobrowolsky, and Katkhouda have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Maas, M.C., Alicuben, E.T., Houghton, C.C. et al. Safety and efficacy of robotic-assisted groin hernia repair. J Robotic Surg 15, 547–552 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11701-020-01140-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11701-020-01140-0