Abstract

Background

Some 28% of the Scottish population suffer from obesity. Bariatric procedures per population carried out in England when compared to Scotland (NBSR 2018) are significantly higher. Primary care practitioners (PCP) influence equality of access to secondary care bariatrics and frequently manage post-operative bariatric patients. Examining changes in PCP knowledge and attitude could improve access to bariatric procedures in Scotland.

Methods

Following a sample pilot, all PCPs within three Scottish NHS health boards were emailed a questionnaire-based survey (2011; n = 902). A subsequent 10-year follow-up encompassed a greater scope of practice, additionally distributed to all PCPs in five further health boards (2021; n = 2049).

Results

Some 452 responses were achieved (2011, 230; 2021, 222). PCPs felt bariatric surgery offered a greater impact in both weight management and that of obesity-related diseases (p < .0001). More PCPs were aware of local bariatric surgical referral criteria (2011, 43%; 2021, 57% (p = .003)), and more made referrals (2011, 60%; 2021, 72% (p = .018)) but were less familiar with national bariatric surgical guidelines (2011, 70%; 2021, 48% (p < .001)). Comfort at managing post-operative bariatric surgical patients were unchanged (2011, 24%; 2021, 27% (p = .660)). Minimal progress through dietetic-lead weight management services, plus rejection of patients thought to be good candidates, was reasons for referral hesitancy.

Conclusion

Over 10 years, PCPs were more aware of local referral criteria, making increased numbers of referrals. Knowledge deficits of national guidelines remain, and overwhelmingly PCPs do not feel comfortable looking after post-operative bariatric surgical patients. Further research into PCP educational needs, in addition to improving the primary to secondary care interface, is required.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There is now an established, widespread recognition of the benefits of bariatric surgery as an adjunct to the loss of excess weight [1]. Bariatric surgery confers a mortality benefit through a reduction of obesity-related diseases: hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and left ventricular hypertrophy [1,2,3]. This results in improvement to quality of life [1]. Since the inception of the UK National Bariatric Surgery Register in 2009 and its transformation into a prospectively maintained database, the annual UK wide number of bariatric procedures has increased from < 6000 to > 8000 in 2018 [4]. However, Scotland-specific numbers have been more modest; 699 procedures were reported between 2013 and 2018 (2.8/100,000 population/year) [4].

The lack of parity of procedural numbers between UK nations is multi-factorial with great variation in both political policy making and funding provision. Eighty percent of bariatric procedures performed in England are NHS funded, whereas only 40% of those in Scotland access public funding [4]. That 28% of the Scottish population suffer from Class III obesity (BMI > 30kg/m2), the heath impacts on individuals and the wider economic burden this confers highlights bariatric surgery to be a key area for expansion [5, 6]. Indeed, bariatric surgery has been repeatedly demonstrated to be the most long-term cost-effective weight loss tool [7, 8].

Primary care plays a key role in the management of pre-, peri-, and post-operative bariatric patients, through the initial engagement and referral and also with regard to the ongoing management of the unique challenges that patients face post-bariatric surgery [9]. Prior studies offering a snapshot of primary care knowledge and attitudes towards bariatric surgery have highlighted PCP reservations in exploring surgical weight loss for their patients [6]. This study aims to provide insight into the changing PCP knowledge and attitudes towards bariatric surgery over time, with the potential to put measures in place to address the disparity of bariatric procedures in Scotland.

Methods

This study was based upon the comparison of two questionnaire-based surveys, completed by PCPs, carried out 10 years apart.

The initial questionnaire (Appendix 1) was created with the aid of prior studies [10,11,12] and was designed to interrogate PCP experience, knowledge, and attitudes towards bariatric surgery. The questionnaire was piloted with a convenience sample of PCPs to test its clarity and content. A link to the online electronic questionnaire was then distributed to all PCPs (n = 902) in the North and East of Scotland, with a predicted response rate of 15% [13]. The data was collected using online survey tool Survey Monkey (Momentive.ai 2019–2021).

Informed by the 2011 study, the follow-up (Appendix 2) was modified and expanded to further interrogate current practice. Similarly, a pilot was performed prior to its distribution using the Webropol online survey tool (Webropol Ltd.), and a response rate of 15% predicted. Accessed through professionally available distribution lists, the study cohort additionally encompassed PCPs from the Scottish Borders, Fife, Dumfries and Galloway, Grampian, and Scottish Highlands Health boards (n = 2049). Responses were anonymised throughout, with only the respondents’ age and sex recorded.

The combined data was entered into Microsoft Excel 2011 and SPSS (IBM SPSS v26.0). Statistical analysis was performed using descriptive statistics, Fisher’s exact test, and Chi-squared analysis.

Results

Demographics and Response

2011 Questionnaire

There were 230 complete responses, a response rate of 25.5% (230/902). One-hundred and twenty-nine respondents (56%) were female. Seventy-four (32%) were aged 25–40 years old, 119 (52%) were aged 41–55, and 37 (16%) were over the age of 55.

2021 Questionnaire

There were 222 completed responses, a response rate of 10.8% (222/2049). One-hundred and thirty-eight respondents (62%) were female. Median age was 45 years old, with a median length of practice 16–24 years. More than 85% of respondents either disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement that they have extensive bariatric surgical experience, with no respondents agreeing.

Question 1:

-

Bariatric surgery has an important role to play in weight management?

According to Table 1, responses from the 2011 cohort showed 61.7% to either agree (51.3%) or strongly agree (10.4%) with this statement, and 16.5% to either disagree (13.5%) or strongly disagree (3.0%). In comparison, 78.8% of responses were in agreement (17.1% strongly) and 5.4% in disagreement (0.9% strongly) in the 2021 cohort (p < 0.001).

Question 2:

-

Bariatric surgery has an important role to play in the management of obesity related co-morbidities?

Of the 2011 cohort, 69.2% of patients (12.2% strongly) were in agreement with the statement that bariatric has an important role to play in the management of obesity-related co-morbidities and 9.1% (1.3% strongly) in disagreement. Agreement was seen in 93.3% (33.8% strongly) in the follow-up 2021 cohort, with 1.4% (0% strongly) in disagreement (p < 0.001), as shown in Table 2.

Question 3:

-

Do you consider the primary role of bariatric surgery to be cosmetic?

Of 220 respondents in 2011, 19 (8.6%) viewed the primary role of bariatric surgery to be cosmetic, compared to 1 in 2021 (0.5%) (p < 0.001).

Questions 4 and 5:

-

Are you familiar with the referral criteria to your local bariatric surgical unit?

-

Are you familiar with the national obesity guidelines (SIGN 115/NICE 189)?

Familiarity with referral criteria to local bariatric surgical units was seen in 42.6% of respondents during the 2011 cohort and in 57.0% of the 2021 cohort (p = 0.003).

The inverse was seen with regard to knowledge of national obesity guidelines; 70.4% responded positively in 2011 compared to 48.0% in the 2021 cohort (p < 0.001).

Question 6:

-

Do you feel equipped to provide long-term care for post-operative bariatric patients?

PCPs did not feel equipped to manage post-operative bariatric surgical patients; 24.3% in 2011 and 26.5% in 2021 responded positively (p = 0.660).

Question 7:

-

Have you ever referred to bariatric surgical services?

Of the PCPs surveyed in the 2021 cohort, 71.7% had made referrals for consideration of metabolic surgery, compared to 60.4% in the 2011 cohort (p = 0.018).

Of those PCPs surveyed in 2021 who had made referrals, 67.5% (108/160) had referred only to NHS services, 3.8% (6/160) had referred only to private care, and 28.7% (46/160) had referred to both private and NHS services.

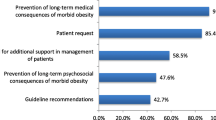

Further questions

A further series of questions probing the reasons for PCPs to be hesitant to refer to secondary care bariatric surgical services were asked as part of the 2021 survey (Table 3). A single white space question was included, and 139 out of 222 (62.6%) responded. This elicited an emotional response and a range of issues were highlighted, as can be seen in Table 4. Many of these answers raised multiple areas of concern.

Discussion

Given the frequency at which PCPs encounter weight management problems (> 90% of PCPs surveyed encounter weight management problems either “often”, or “very often”), and their role as the primary point of patient contact, this study highlights the magnitude of the problem and underlines the relevance of PCP opinion.

Several studies have previously proposed a negative bias towards patients with obesity by healthcare providers, and asking PCPs their views on cosmesis as the primary role of bariatric surgery acted as a surrogate for identifying this [12, 14, 15]. The decrease (8.6 to 0.5%) in the proportion of PCPs who viewed bariatric surgery as a primarily cosmetic procedure is encouraging.

Overall PCP awareness of referral guidelines has been shown to be around 65% in prior studies [16], and this is broadly similar to those highlighted by our study. Seventy percent of PCPs in the 2011 cohort were familiar with existing NICE/SIGN guidelines. The 22% fall in awareness of guidelines in the subsequent cohort is somewhat worrying, especially considering the increased profile of bariatric surgery over this time [17]. Nevertheless, a greater proportion of PCPs have made secondary care bariatric surgical referrals when compared to the previous decade, but whether some patients’ geographical location is a preventative factor to referral remains an argument for debate.

We have seen a significant increase in the views amongst PCPs that bariatric surgery has an important role in weight management, as well as the management of obesity-related diseases. This is in keeping with a large body of evidence that this approach offers both effective long-term weight loss and reduction in all-cause mortality, as well as offering cost-effectiveness [1, 18]. However, despite this recognition, we are yet to see the subsequent increase in bariatric surgical procedures performed in Scotland, 2.6/100,000 population/year between 2013 and 2018 [4]; though it should be noted that unlike English surgical practice, compulsory registration of Scottish cases through the national registry is not yet enforced. A 2016 article from Welbourn et al. highlighted a series of barriers of access to bariatric surgical care [19]; the tiered, dietetic-lead weight management service was highlighted as one such barrier, and this is echoed in the free text response analysis in our study. Out of 139, 39 (30%) respondents saw this as the main bottleneck to surgery, and the strongly negative, emotive response of PCPs when asked about the Scottish secondary care bariatric surgical service is almost universal. To further cement this view, more recent data presented at the 2021 BOMSS conference [20] suggested that increased length of time spent in tier 3 weight loss services did not affect percentage total body weight loss and reiterated that this service acts a barrier to progression to MBS.

The BOMMS nutritional guidelines 20 outline post-operative management following bariatric surgery, and in recent years, these have been supplemented with those from the European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO) [21, 22]. Both underline the importance of ongoing long-term follow-up, recognising that as rates, of bariatric surgery increase, the burden of aftercare, once follow-up through the bariatric multidisciplinary team has concluded, will fall to primary care [7, 21, 22]. Whilst specialised surgical services can be consulted in the more acute or complex cases, routine follow-up will require both primary care capacity and PCP knowledge for this to be safely provided. Low proportions of PCPs who are confident in looking after post-operative bariatric surgical patients, 24.3% and 26.5% in 2011 and 2021, respectively, suggest inadequacy of current services and that wider dissemination of knowledge to primary care is essential. Lack of PCP comfort in managing post-operative patients is not a finding unique to the Scottish healthcare system; only 44% of PCPs surveyed in an American study were confident in looking after post-operative bariatric surgical patients [16].

PCPs were not deterred from referring to secondary care services because of perceived surgical risk, as evidenced by > 60% of those sampled either disagreeing or strongly disagreeing with the development of short- or medium-term surgical complications as a cause of hesitancy. Perceived lack of progression to surgery in candidates PCPs thought to be suitable, however, could be seen as a possible barrier to access; > 50% of respondents either agreeing or strongly agreeing with this statement. Only 7.5% of primary care practitioners based in the American healthcare setting identified this as a perceived barrier to access; the potential for this negatively affecting consideration of referral in the Scottish NHS needs addressing [22].

We acknowledge that this cross-sectional survey has limitations. The use of a non-validated survey restricts our ability to draw significant conclusions, the capacity for investigating causative factors is limited, and there remains a potential response bias. However, those surveyed encompass a large geographical area with a diverse rural and urban population representative of the Scottish population and with a sufficient cohort size to adequately analyse results.

Conclusion

Although there is scope for improvement, over 10 years, more PCPs are aware of local referral criteria and have made referrals to secondary care weight loss services.

Deficits remain to PCP knowledge surrounding national guidelines, and the vast majority of PCPs do not feel comfortable managing post-operative bariatric surgical patients. This is unchanged over the 10-year period, highlighting the need for further research into PCP educational needs.

The notable dissatisfaction towards secondary care weight management services by PCPs could preclude fair access to services and further work is required in order to improve the primary to secondary care interface.

The findings of this study need to be validated in future studies with a representative sample and psychometrically validated survey.

Data Availability

Informed consent was obtained from all individuals completing the questionnaire. Data can be obtained upon request from authors.

References

Carlsson LMS, Peltonen M, Ahlin S, Anveden Å, Bouchard C, et al. Bariatric surgery and prevention of type 2 diabetes in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:695–704.

Perego L, Pizzocri P, Corradi D, et al. Circulating leptin correlates with left ventricular mass in morbid (grade III) obesity before and after weight loss induced by bariatric surgery: a potential role for leptin in mediating human left ventricular hypertrophy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(7):4087–93. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2004-1963.

Yusefzadeh H, Rashidi A, Rahimi B. Economic burden of obesity: a systematic review. Soc Health Behav. 2019;2:7–12.

National Bariatric Surgery Registry. The UK National Bariatric Surgery Registry Third Registry Report. 2020. https://www.e-dendrite.com/NBSR2020. Accessed 12 Oct 2022.

The Scottish government, Scottish Health Survey 2020 Volume 1; main report. September 2020. Accessed 20/03/2022. Chapter 4: Diet, Obesity & Food Insecurity - Scottish Health Survey – telephone survey – August/September 2020: main report - gov.scot (http://www.gov.scot)

Boyers D, Retat L, Jacobsen E, et al. Cost-effectiveness of bariatric surgery and non-surgical weight management programmes for adults with severe obesity: a decision analysis model. Int J Obes. 2021;45:2179–90. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-021-00849-8.

Welbourn R, le Roux CW, Owen-Smith A, Wordsworth S, Blazeby JM. Why the NHS should do more bariatric surgery; how much should we do? BMJ. 2016May;11(353):i1472. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i1472.

Busetto L, Dicker D, Azran C, et al. Obesity management task force of the European Association for the study of obesity released “practical recommendations for the post-bariatric surgery medical management.” Obes Surg. 2018;28:2117–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-018-3283-z.

Balduf LM, Farrell TM. Attitudes, beliefs, and referral patterns of PCPs to bariatric surgeons. J Surg Res. 2008Jan;144(1):49–58.

Sansone RA, McDonald S, Wiederman MW, Ferreira K. Gastric bypass surgery: a survey of primary care physicians. Eat Disord. 2007;15(2):145–52.

Foster GD, Wadden TA, Makris AP, Davidson D, Sanderson RS, Allison DB, Kessler A. Primary care physicians’ attitudes about obesity and its treatment. Obes Res. 2003;11(10):1168–77.

Weaver L, Beebe TJ, Rockwood T. The impact of survey mode on the response rate in a survey of the factors that influence Minnesota physicians’ disclosure practices. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19:73. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0719-7.

Hebl MR, Xu J. Weighing the care: physicians’ reactions to the size of a patient. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:1246–52.

Harvey EL, Hill AJ. Health professionals’ views of overweight people and smokers. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25(8):1253–61.

Tork S, Meister KM, Uebele AL, et al. Factors influencing primary care physicians’ referral for bariatric surgery. JSLS. 2015;19(3):e2015.00046. https://doi.org/10.4293/JSLS.2015.00046.

Panteliou E, Miras AD. What is the role of bariatric surgery in the management of obesity? Climacteric. 2017;20(2):97–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/13697137.2017.1262638.

Boyers D, Retat L, Jacobsen E, et al. Cost-effectiveness of bariatric surgery and non-surgical weight management programmes for adults with severe obesity: a decision analysis model. Int J Obes. 2021;45:2179–90. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-021-00849-8.

Welbourn R, le Roux CW, Owen-Smith A, Wordsworth S, Blazeby JM. Why the NHS should do more bariatric surgery; how much should we do? BMJ. 2016;353:i1472. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i1472. (Published 2016 May 11).

Arhi C, Karagianni C, Howse L, et al. The effect of participation in tier 3 services on the uptake of Bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2021;31:2529–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-021-05303-2.

O’Kane M, Parretti HM, Pinkney J, et al. British obesity and metabolic surgery society guidelines on perioperative and postoperative biochemical monitoring and micronutrient replacement for patients undergoing bariatric surgery—2020 update. Obesity Reviews. 2020;21:e13087. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.13087

Durrer Schutz D, Busetto L, Dicker D, Farpour-Lambert N, Pryke R, Toplak H, Widmer D, Yumuk V, Schutz Y. European practical and patient-centred guidelines for adult obesity management in primary care. Obes Facts. 2019;12:40–66. https://doi.org/10.1159/000496183.

Conaty EA, Denham W, Haggerty SP, et al. Primary care physicians’ perceptions of bariatric surgery and major barriers to referral. Obes Surg. 2020;30:521–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-019-04204-9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Key points

1. Investigating understanding of PCPs in Scotland towards bariatric surgery.

2. Overall, greater appreciation of operative weight loss surgery is achieved.

3. Demonstrable dissatisfaction of tier 3 weight loss services by PCPs.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Douglass, B., Lau, S.H., Parkin, B. et al. Changing Knowledge and Attitudes towards Bariatric Surgery in Primary Care: a 10-Year Cross-Sectional Survey. OBES SURG 34, 71–76 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-023-06934-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-023-06934-3