Abstract

Background

Bariatric surgery is an effective method for treating morbid obesity and improving patientsʼ health-related quality of life (HRQoL). As research on predictors that contribute to the amelioration of HRQoL is sparse, our prospective study was conducted to examine the predictive value of demographic, psychological and physiological variables on physical and mental HRQoL 6 and 12 months after surgery.

Methods

We surveyed 154 participants who had undergone either a laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) or a laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG). Prior to surgery and both 6 and 12 months after the procedure, patients completed questionnaires concerning their demographic data, height and weight, co-morbid conditions, HRQoL (Short Form Health Survey-12), depression severity (Beck Depression Inventory-II), and eating psychopathology (Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire). Multiple linear regression analyses were conducted to detect predictors of physical and mental HRQoL 6 and 12 months post-operation.

Results

The predictors included within the models explained 50 to 58% of the variance of post-operative physical and mental HRQoL, respectively. Higher baseline depression severity was associated with reduced HRQoL after surgery, whereas changes from pre- to post-surgery in BDI-II scores positively predicted HRQoL values, especially mental HRQoL. The persistence of somatic co-morbid disorders had a negative effect on physical HRQoL.

Conclusions

Depression severity before surgery and changes in depression scores were found to be major predictors of HRQoL after bariatric surgery. Therefore, we recommend screening patients regularly for depression both before and after bariatric surgery and offering them adequate psychotherapeutic and/or psychopharmacologic support.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Instances of overweight and obesity are increasing worldwide at a pace that is alarming [1]. They contribute to an elevated risk of several diseases, and thus have a serious impact on health and economic systems [2].

One of the most effective treatments within this sector is bariatric surgery, a procedure that has a huge influence on weight loss and the improvement of coexisting diseases (e.g., hypertension) in people with severe obesity (body mass index (BMI) ≥ 40 kg/m2) [3]. Another major outcome is the amelioration of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [4]. In their review on the impact of bariatric surgery on HRQoL, Lindekilde et al. [5] propose that improvements are significantly higher on scales measuring physical, as opposed to mental, HRQoL. This finding implies that improvements in physical and mental HRQoL seem to be predicted by factors beyond that of the surgical intervention alone. Therefore, several variables have been examined regarding their predictive value for patients´ HRQoL after bariatric surgery.

Primarily, the magnitude of weight loss was confirmed to predict improvements in HRQoL [6] and mental health [7]. Some studies show, however, that there is no constant relation between those variables [8, 9], indicating that additional factors have an impact on post-operative HRQoL.

Wimmelmann and colleagues [7] reviewed the influence of psychological predictors on HRQoL and/or mental health. They found that enhanced post-surgical HRQoL scores were positively influenced by the absence of a severe mental disorder prior to surgery and the improvement of psychological issues, especially depressive symptoms, after the bariatric procedure [10, 11]. Persisting mental health problems like depressive symptoms [11] and uncontrolled eating behaviour [12] were found to negatively influence post-operative HRQoL values.

Few studies combined several predictive factors when examining their impact on HRQoL after bariatric surgery. Whereas in some surveys [13, 14], demographic data, information regarding the surgical procedure and weight status were used to calculate a predictive model of HRQoL, others only considered the value of psychosocial variables [15]. A more comprehensive approach was undertaken by Brunault et al. [16] who based their predictive calculation on a working model that included individual and environmental characteristics, biological and physiological variables, and symptom status. Predictors they found were, next to weight loss, pre-operative levels of depression and binge eating. Their conclusions were consistent with those of prior research [7] as they found that psychological variables in particular should be taken into account when predicting HRQoL outcomes after bariatric surgery.

The objective of our analyses was to generate predictive models for patientsʼ physical and mental HRQoL 6 and 12 months after bariatric surgery in an explorative way, including further variables. We especially focused on examining psychological variables since they seem to have a major impact on bariatric surgery outcomes. In particular, as levels of depression and disordered eating may alter after surgery, we wanted to analyse whether such changes then affect HRQoL. As in other recent studies, pre-operative BMI and weight loss [6] were considered potential predictors of HRQoL and were therefore included in the analyses. Other possible causal variables we included in the calculation were as follows: the existence and persistence of co-morbid somatic diseases (because improvement of these has been shown to influence improved HRQoL scores [17]) and demographic data like age, gender, partnership and employment.

Materials and Methods

Participants

The present study was conducted at the Integrated Research and Treatment Center (IFB) Adiposity Diseases and the Department of Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy at the University Hospital of Leipzig. It was approved by the local ethical committee. Patients were recruited during pre-operative surgical consultations at least 3 weeks prior to surgery. Inclusion criteria were as follows: BMI exceeding 40 kg/m2 or BMI exceeding 35 kg/m2 if accompanied by an obesity-related disease (e.g., diabetes), aged 18 to 65 years old, sufficient German language skills and provision of written informed consent. Of the 236 patients who met the inclusion criteria and were potentially available for follow-up measurements to be taken up through 12 months after their surgery, 202 filled out questionnaires at baseline (85.59%). We excluded 11 patients who had not undergone a primary bariatric procedure and 37 who did not complete follow-up surveys. This resulted in a final total of 154 patients (76.24% of the baseline population). Their surgeries took place between November 2011 and April 2014, and the types of procedures carried out were laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB, 88.3%) and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG, 11.7%).

Measures

Patients were assessed prior to surgery and both 6 and 12 months thereafter. At all measuring points, we gathered information on demographic data including age, gender, marital status, education and employment. Furthermore, current height and weight and the existence of co-morbid somatic diseases like hypertension, diabetes mellitus and joint pain were assessed. Data on weight and/or BMI were also collected routinely prior to surgery and during follow-up visits at the obesity outpatient clinic. When applicable, we used objective weight data to calculate BMI and percent excess weight loss (%EWL); otherwise, self-reported values were included.

HRQoL was measured with the Short-Form (SF-12) Health-Survey [18], a self-report questionnaire of which the component scales for physical (PCS) and mental HRQoL (MCS) can be calculated. It is a brief version of the Short-Form (SF-36) Health-Survey and has been proven to show high correlations with SF-36 in patients with obesity [19]. The severity of depressive symptoms was assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) [20] whereby a cut-off score of 14 indicates the existence of a major depressive episode [21]. The Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire (EDE-Q) [22] was used to measure eating disorder psychopathology and in particular episodes of binge eating and loss of control eating [23]. As there is a close cooperation between the obesity outpatient clinic and the Department of Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy, a psychological consultation was offered regularly to all patients with increased scores on the psychopathological scales.

Statistical Methods

Analyses were conducted using SPSS, Version 20. In addition to descriptive data, repeated measures ANOVAs were conducted to evaluate changes in body weight, BMI, depression severity, the EDE-Q global score, binge eating severity, and loss of control eating between the three measuring points. This was also done for the two component scales of the SF-12. Subsequently, post hoc tests with an adjusted significance level (p < 0.01) were conducted. Within-group effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were calculated to compare levels of HRQoL between the three survey points. Values such as 0.2 or 0.3 are small, a medium effect size is 0.5, and values >0.8 are considered large [24].

We used multiple linear regression analyses to generate a predictive model for HRQoL after bariatric surgery. First, to replace missing values, single imputation was done using NORM software with an expectation-maximization algorithm [25]. Pearson’s bivariate correlations were performed between potential predictors and the two component scales at the 6- and 12-month follow-up time points. The variables tested were as follows: age, gender, education and employment, BMI before surgery and the change of BMI from baseline to 6 or 12 months. The types of surgical procedure performed and the co-morbid somatic diseases present before and after bariatric surgery were also analysed. The psychological variables examined were as follows: pre-surgical and changing scores between baseline and the 6- or 12-month follow-up time points of the BDI-II, global EDE-Q, binge-eating severity and loss of control eating. Only predictors that correlated with the outcome variables at a significance level of p < 0.20 were included in the regression analyses [26]. The exceptions to this were age and gender, factors that were included in all models. Multiple linear regression was conducted using a stepwise method of variable inclusion (PIN = 0.05 POUT = 0.10). We calculated four separate models for the two SF-12 component scales at the 6- and 12-month follow-up time points. In addition, the variance inflation factor (VIF) was calculated to examine multicollinearity between the independent variables. The cut-off score was 5 [27].

Results

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of our study sample at the three measuring points. The majority of our patients were female (69.5%), their mean age was 47 years (SD = 10.58) and their mean BMI 50 kg/m2 (SD = 7.95). Significant decreases in body weight and BMI were recorded, and the average %EWL 12 months after the surgical procedure was 60.84 ± 19.91%. Also, depressive symptoms (BDI-II) and eating pathology (EDE-Q) decreased significantly.

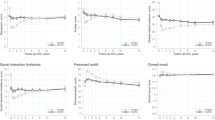

Changes in the SF-12 scores from baseline assessments to both the 6- and 12-month follow-up time points are presented in Table 2. The PCS improved significantly over the total 12-month period (p < 0.001), as is affirmed by the large effect sizes (t0-t1: 0.99; t0-t2: 1.08). A significant increase was also found for the MCS (p < 0.001). Calculated effect sizes were small to medium (t0-t1: 0.42; t0-t2: 0.44). As post hoc tests indicate, the most significant increases for both scales were found between the baseline assessments and 6 months thereafter. Between 6 and 12 months after surgery, the MCS remained stable whereas for the PCS, a significant improvement was found.

Table 3 lists all variables that had a significant correlation (p < 0.2) to PCS or MCS at the 6-month follow-up time point and were therefore included in the regression analyses. β-Coefficients, p values and the VIF are specified for those predictors, which substantially contributed to the explanation of variance in the outcome. The regression model predicting PCS after 6 months consists of 8 variables which explain 54% of the variance. Variables with the highest predictive value for the PCS scale were as follows: an improved depression score, higher expressions of PCS before surgery and, with a negative influence, the magnitude of depressive symptoms at baseline assessment. The persistence of hypertension and joint pain represented relevant factors for lower physical HRQoL post-surgery. Being female, employed and living in a partnership were found to have a positive influence. Mental HRQoL at this time point was predicted by three factors, which explain 58.5% of the variance. Decreasing depressive symptoms had a positive impact, whereas higher depression severity at baseline assessment predicted declining scores on the MCS. Patients who had higher pre-surgery MCS scores reported having better mental HRQoL after the procedure.

Predictors of physical and mental HRQoL 12 months post-operation are listed in Table 4. The predictive model of physical HRQoL 12 months after bariatric surgery consists of 6 predictors that explain 50% of the variance. The most relevant predictor of a higher PCS score 12 months post-operation was better physical HRQoL at baseline. The continued existence of hypertension, diabetes and joint pain 1 year post-surgery negatively influenced patientsʼ physical HRQoL. Employment and greater amounts of weight loss (BMI change) had a positive influence on physical HRQoL. Four predictors were found that explain 51% of the variance when predicting MCS 12 months post-operation. Again, the reduction of depressive symptoms had a positive influence on mental HRQoL, and higher depression scores at baseline negatively influenced the outcome. Higher mental HRQoL scores before surgery and reported hypertension at baseline were found to predict higher MCS scores at the 12-month follow-up time point.

As VIF values are below 5, there is no indication of multicollinearity.

Conclusion

The aim of the present study was to ascertain models of variables predicting patientsʼ physical and mental HRQoL 6 and 12 months after bariatric surgery. It can be emphasized that a combination of demographic, psychological and physiological variables was found to explain an important percentage of the improvements in HRQoL. The calculated models for predicting physical and mental HRQoL differed though in their composition of variables. Notably, higher baseline depression severity and a lower amelioration of the depression score strongly influenced poorer mental HRQoL improvement, whereas lower physical HRQoL was essentially predicted by the persistence of obesity-related diseases.

As recently published literature [13, 14] has primarily focused on relatively few variables and their impact on HRQoL, the wide range of analysed predictors our study took into consideration allows us to contribute new knowledge about what influences HRQoL after bariatric surgery. In particular, the inclusion of changing scores of psychological constructs like depression and eating disorder symptoms rather than just baseline values extends previous literature.

A major finding of our analyses is that the existence of a depressive disorder prior to surgery has a huge negative influence on how much HRQoL improves after surgery, especially the mental scale. The amelioration of depressive symptoms on the other hand accounts for higher scores on the SF-12 scales. Prior scientific work has shown that patients with higher pre-operative and/or post-operative depression scores report lower HRQoL [11, 28]. Investigations have also been done to determine whether patients with depressive symptoms benefit less from surgery. The results have thus far been inconsistent, especially regarding weight loss [29]. Some studies indicate post-operative depression to be associated with less long-term weight loss [28, 30]. Because long-term studies found out that, after an initial decline of depressive scores after surgery, over time patients’ symptoms tend to increase and even reach pre-surgery levels [28, 31], it can be assumed that these patients experience less weight loss. This could also be explained by the finding that patients with higher depression scores or diagnosed clinical depression missed surgery follow-up appointments more often than other patients [32] and, as a result, may not have been complying with post-operative recommendations. Another important issue is the increased risk of bariatric patients committing suicide after surgery [33], something which could be influenced by persisting depressive disorders and/or reduced HRQoL values [34]. Patients with co-morbid psychiatric disorders should not be excluded from bariatric procedures [35]. But with regard to the mentioned findings and the fact that mood disorders are the most frequent psychiatric co-morbid disorders in patients undergoing bariatric surgery [36], it is necessary to screen routinely for depression in this population. Depressive disorders can be treated successfully with psychotherapy and/or psychopharmacotherapy. These services should be offered to support successful weight loss, the amelioration of HRQoL and the maintenance of these improvements. Recent studies on pre-operative supportive therapeutic programmes for patients with obesity and those undergoing bariatric surgery were shown to reduce depressive symptoms [37, 38].

We found the physical HRQoL scale being negatively influenced by the persistence of obesity-related diseases at both follow-up points. Results are ambiguous among current studies as, on the one hand, patients without co-morbidities report higher HRQoL [39], but on the other hand, co-morbid somatic disorders do not seem to influence either baseline HRQoL values or the degree to which these scores improve post-operatively [40]. However, patients without co-morbidities showed higher scores (though not significantly so) than those with sequelae [40]. In general, patientsʼ intention in undergoing bariatric surgery is a substantial physical and psychological improvement [41] as well as losing weight and the remission or alleviation of somatic diseases [42]. Because patients’ expectations are often high or even unrealistic [41], the persistence of co-morbidities and unsatisfactory weight loss after surgery may contribute to them having a worse perception of their physical and mental HRQoL after surgery, or even experiencing a depressive reaction and subsequent reduced adherence to recommended behavioural regimens. It is therefore necessary that patients receive adequate education prior to surgery and be given continuous support by nutritionists and psychologists. This could contribute to them having more realistic expectations and therefore increased contentment with their achievements.

Neither the severity of pre-operative eating pathology, binge eating and loss of control eating nor changing scores of those variables had a significant predictive value for post-operative HRQoL. Previous publications have had contradictory findings as to whether pre-operative eating psychopathology like binge eating and loss of control eating have a substantial influence on post-operative HRQoL values or not [16, 43]. Besides those outcomes, it should be emphasized that most studies found a strong association between the development or the recurrence of eating psychopathology and less weight loss or even weight regain after bariatric surgery [44]. Furthermore, there is a strong connection between eating disturbances and other psychiatric disorders [45] implying a need to identify patients with a risk of developing disordered eating behaviour and to offer them psychotherapeutic support to assure positive long-term surgery outcomes.

The study also has some limitations. Our analyses focused on a relatively small sample that underwent surgery at one institution. This may limit the generalizability of our results. Another limitation is the short duration of follow-up. Major improvements in HRQoL occur 6 and 12 months after surgery [46], but long-term results have had conflicting outcomes. Some have reported improvements [4] or relatively stable values [47], while others have shown that early improvements in HRQoL diminish over time [31, 48], and Karlsson et al. [46] have described a decline of HRQoL next to weight regain until 6 years after surgery but a stabilization of the values after that. Future long-term studies could clarify whether HRQoL values change or stabilize long-term and identify predictors of long-term HRQoL. We did not systematically collect information regarding the attendance, duration and intensity of psychotherapeutic and/or psychopharmacological treatment of the patients which is a weakness of the study design since this could have a moderating effect on the outcome data. Otherwise, improvements on the psychological scales were found for the whole sample which points to a substantial influence of the surgery and weight loss, respectively. Recent investigation found a strong correlation between weight loss and improving depression scores, but no clear causality can be emphasized [49, 50]. Similar results were reported in people with obesity undergoing a lifestyle intervention with or without a supplementary depression treatment [51]. Additionally offered programmes like comprehensive behavioural-motivational nutrition information [49] or depression treatment [51] were shown to increase the positive effect of weight loss on the improvement of depression scores. Although there is a remission rate of 53% of untreated major depressive disorder over the time course of 1 year [52], our results and those of prior researches can support the positive influence of weight loss on depression scores. Nonetheless, regular screening for psychological disturbances and the offer of psychotherapeutic support and/or regularly implemented groups after surgery should be a substantial part of the follow-up care. Patients with persisting depressive episodes should be paid particular attention to as they often lose less weight [53] which bears the risk of frustration and continuative ongoing psychological disturbances and even suicide [33].

A further limitation is the use of a generic instrument for measuring HRQoL that is not specific to obesity and bariatric surgery [54]. Nevertheless, the SF-36 is the questionnaire most used in bariatric samples [54], and since the SF-12 correlates closely to the SF-36 for obesity [19], our results can be compared to those of other studies. At the same time, Tayyem and colleagues [55] propose that neither generic nor obesity-specific instruments have sufficient content validity and that new bariatric specific instruments should be developed. Hence, future studies could include several questionnaires measuring generic, obesity-specific, and bariatric surgery-specific aspects to obtain a more global view of HRQoL.

In conclusion, this study shows that predicting HRQoL after bariatric surgery relies on taking a number of variables into account including pre-operative characteristics and changing variables. The predictors with the highest proportion of incremental variance were baseline depression scores and changes in depression severity, both of which influence physical and mental HRQoL. Therefore, psychological screening should be conducted at regular intervals as a matter of routine, and psychotherapeutic assistance should be given as needed to support successful bariatric surgery outcomes.

References

Swinburn BA, Sacks G, Hall KD, et al. The global obesity pandemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet. 2011;378:804–14.

Wang YC, McPherson K, Marsh T, et al. Health and economic burden of the projected obesity trends in the USA and the UK. Lancet. 2011;378:815–25.

Picot J, Jones J, Colquitt J, et al. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of bariatric (weight loss) surgery for obesity: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess Winch Engl. 2009;13:1–190.

Driscoll S, Gregory DM, Fardy JM. Long-term health-related quality of life in bariatric surgery patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016;24:60–70.

Lindekilde N, Gladstone BP, Lübeck M, et al. The impact of bariatric surgery on quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2015;16:639–51.

Sarwer DB, Lavery M, Spitzer JC. A review of the relationships between extreme obesity, quality of life, and sexual function. Obes Surg. 2012;22:668–76.

Wimmelmann CL, Dela F, Mortensen EL. Psychological predictors of mental health and health-related quality of life after bariatric surgery: a review of the recent research. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2014;8:e314–24.

Mar J, Karlsson J, Arrospide A, et al. Martínez de Aragón G, Martinez-Blazquez C. Two-year changes in generic and obesity-specific quality of life after gastric bypass. Eat Weight Disord. 2013;18:305–10.

Fezzi M, Kolotkin R, Nedelcu M, et al. Improvement in quality of life after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2011;21:1161–7.

Lier HØ, Biringer E, Hove O, et al. Quality of life among patients undergoing bariatric surgery: associations with mental health- a 1 year follow-up study of bariatric surgery patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:79.

Masheb RM, White MA, Toth CM, et al. The prognostic significance of depressive symptoms for predicting quality of life 12 months after gastric bypass. Compr Psychiatry. 2007;48:231–6.

Colles SL, Dixon JB, O’Brien PE. Grazing and loss of control related to eating: two high-risk factors following bariatric surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008;16:615–22.

Khandalavala B, Geske J, Nirmalraj M et. al. Predictors of health-related quality of life after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2015;1–4.

Janik MR, Rogula T, Bielecka I, Kwiatkowski A, Paśnik K. Quality of life and bariatric surgery: cross-sectional study and analysis of factors influencing outcome. Obes Surg. 2016;1–7.

van Hout GC, Hagendoren CA, Verschure SK, et al. Psychosocial predictors of success after vertical banded gastroplasty. Obes Surg. 2009;19:701–7.

Brunault P, Frammery J, Couet C, et al. Predictors of changes in physical, psychosocial, sexual quality of life, and comfort with food after obesity surgery: a 12-month follow-up study. Qual Life Res. 2015;24:493–501.

Julia C, Ciangura C, Capuron L, et al. Quality of life after roux-en-Y gastric bypass and changes in body mass index and obesity-related comorbidities. Diabetes Metab. 2013;39:148–54.

Bullinger M, Kirchberger I. Fragebogen zum Gesundheitszustand. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 1998.

Wee CC, Davis RB, Hamel MB. Comparing the SF-12 and SF-36 health status questionnaires in patients with and without obesity. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:11.

Hautzinger M, Keller F, Kühner C. Beck Depressions-Inventar (BDI-II). Harcourt Test Services: Frankfurt; 2006.

Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck depression inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1996.

Hilbert A, Tuschen-Caffier B. Eating disorder examination-questionnaire: Deutschsprachige Übersetzung (Bd. 02). Münster: Verlag für Psychotherapie; 2006.

Reas DL, Grilo CM, Masheb RM. Reliability of the eating disorder examination-questionnaire in patients with binge eating disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44:43–51.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988.

Schafer JL. NORM: Multiple imputation of incomplete multivariate data under a normal model. (Version 2.03, Computer software). Retrieved October 12, 2007. 1999.

Robitail S, Siméoni M-C, Ravens-Sieberer U, et al. Children proxies’ quality-of-life agreement depended on the country using the European KIDSCREEN-52 questionnaire. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:469.e1–469.e13.

Farin E, Meder M. Personality and the physician-patient relationship as predictors of quality of life of cardiac patients after rehabilitation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:100.

White M, Kalarchian M, Levine M, Masheb R, Marcus M, Grilo C. Prognostic significance of depressive symptoms on weight loss and psychosocial outcomes following gastric bypass surgery: a prospective 24-month follow-up study. Obes Surg. 2015;1–8.

Dawes AJ, Maggard-Gibbons M, Maher AR, et al. Mental health conditions among patients seeking and undergoing bariatric surgery: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;315:150–63.

de Zwaan M, Enderle J, Wagner S, et al. Anxiety and depression in bariatric surgery patients: a prospective, follow-up study using structured clinical interviews. J Affect Disord. 2011;133:61–8.

Herpertz S, Müller A, Burgmer R, et al. Health-related quality of life and psychological functioning 9 years after restrictive surgical treatment for obesity. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015;11:1361–70.

Toussi R, Fujioka K, Coleman KJ. Pre- and postsurgery behavioral compliance, patient health, and postbariatric surgical weight loss. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2009;17:996–1002.

Peterhänsel C, Petroff D, Klinitzke G, et al. Risk of completed suicide after bariatric surgery: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2013;14:369–82.

Mitchell JE, Crosby R, de Zwaan M, et al. Possible risk factors for increased suicide following bariatric surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013;21:665–72.

Peterhänsel C, Wagner B, Dietrich A, et al. Obesity and co-morbid psychiatric disorders as contraindications for bariatric surgery?—a case study. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2014;5:1268–70.

White MA, Masheb RM, Rothschild BS, et al. The prognostic significance of regular binge eating in extremely obese gastric bypass patients: 12-month postoperative outcomes. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:1928–35.

Wild B, Herzog W, Wesche D, et al. Development of a group therapy to enhance treatment motivation and decision making in severely obese patients with a comorbid mental disorder. Obes Surg. 2011;21:588–94.

Cassin SE, Sockalingam S, Du C, et al. A pilot randomized controlled trial of telephone-based cognitive behavioural therapy for preoperative bariatric surgery patients. Behav Res Ther. 2016;80:17–22.

Raoof M, Näslund I, Rask E, et al. Health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) on an average of 12 years after gastric bypass surgery. Obes Surg. 2015;25:1119–27.

Risstad H, Søvik T, Hewitt S, Kristinsson J, Fagerland M, Bernklev T, et al. Changes in health-related quality of life after gastric bypass in patients with and without obesity-related disease. Obes Surg. 2015;1–9.

Homer CV, Tod AM, Thompson AR, et al. Expectations and patients’ experiences of obesity prior to bariatric surgery: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e009389.

Fischer L, Nickel F, Sander J, et al. Patient expectations of bariatric surgery are gender specific—a prospective, multicenter cohort study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10:516–23.

White MA, Kalarchian MA, Masheb RM, et al. Loss of control over eating predicts outcomes in bariatric surgery: a prospective 24-month follow-up study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:175–84.

Meany G, Conceição E, Mitchell JE. Binge eating, binge eating disorder and loss of control eating: effects on weight outcomes after bariatric surgery. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2014;22:87–91.

Jones-Corneille LR, Wadden TA, Sarwer DB, et al. Axis I psychopathology in bariatric surgery candidates with and without binge eating disorder: results of structured clinical interviews. Obes Surg. 2012;22:389–97.

Karlsson J, Taft C, Ryden A, et al. Ten-year trends in health-related quality of life after surgical and conventional treatment for severe obesity: the SOS intervention study. Int J Obes. 2007;31:1248–61.

Kolotkin RL, Davidson LE, Crosby RD, et al. Six-year changes in health-related quality of life in gastric bypass patients versus obese comparison groups. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8:625–33.

Canetti L, Bachar E, Bonne O. Deterioration of mental health in bariatric surgery after 10 years despite successful weight loss. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70:17–22.

Petasne Nijamkin M, Campa A, Samiri Nijamkin S, et al. Comprehensive behavioral-motivational nutrition education improves depressive symptoms following bariatric surgery: a randomized, controlled trial of obese hispanic americans. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2013;45:620–6.

Júnior WS, do Amaral JL, Nonino-Borges CB. Factors related to weight loss up to 4 years after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2011;21:1724–30.

Pagoto S, Schneider KL, Whited MC, et al. Randomized controlled trial of behavioral treatment for comorbid obesity and depression in women: the Be active trial. Int J Obes. 2013;37:1427–34.

Whiteford H, Harris M, McKeon G, et al. Estimating remission from untreated major depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2013;43:1569–85.

Rydén A, Torgerson JS. The Swedish obese subjects study—what has been accomplished to date? Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2006;2:549–60.

Coulman KD, Abdelrahman T, Owen-Smith A, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in bariatric surgery: a systematic review of standards of reporting. Obes Rev. 2013;14:707–20.

Tayyem R, Ali A, Atkinson J, et al. Analysis of health-related quality-of-life instruments measuring the impact of bariatric surgery. Patient. 2011;4:73–87.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), Germany, FKZ: 01EO1001.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Peterhänsel, C., Nagl, M., Wagner, B. et al. Predictors of Changes in Health-Related Quality of Life 6 and 12 months After a Bariatric Procedure. OBES SURG 27, 2120–2128 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-017-2617-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-017-2617-6