Abstract

Knowledge co-production enabled via decolonised research approaches can support indigenous leaders to respond to the challenges and opportunities that result from their natural and cultural resource management obligations and strategies. For knowledge co-production to be realised, such research interactions must provide space for Indigenous peoples to position themselves as research leaders, driving agendas and co-designing research approaches, activities, and outputs. This paper examines the role that positionality played in supporting an Indigenous-led research partnership, or knowledge-action system, that developed between indigenous, industry, and research project partners seeking to support development of the Indigenous-led bush products sector in northern Australia. Our chosen conceptualisation of positionality informs sustainability science as a way for scientists, practitioners, and research partners to consider the power that each project member brings to a project, and to make explicit the unique positioning of project members in how they influence project processes and the development of usable knowledge. We locate the research in northern Australia and then articulate how selected research methodologies supported the partnership that resulted in knowledge co-production. We then extend the literature on decolonising methodologies and positionality by illuminating how the positionality of each research partner, and the partnership itself, influenced the research and knowledge co-production processes. In culmination, we reveal how an interrogation of post-project benefits and legacies (e.g., usable knowledge) can enable a fuller understanding of the lasting success of the project and partnership, illustrated with examples of benefits derived by project partners since the project ended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Worldwide, Indigenous peoples seek research partnerships that support and empower their unique and diverse resource governance and management strategies and enable the co-production of useful context specific knowledge (e.g., Coombes et al. 2014; Fermantez 2013; Johnson et al. 2007, 2016; Chartier 2015; Maclean et al 2019; Zurba et al. 2019; Woodward et al. 2020). Many Indigenous leaders seek partnerships with researchers who themselves identify as Indigenous and may practice Indigenist research that claim “the rights of self-definition, the right to tell their own histories, recover their own traditional knowledge and culturally grounded pedagogies, epistemologies and ontologies” (Stewart-Harawira 2013:41; see also Coombes et al. 2014). Indigenous leaders may also choose to build partnerships with non-indigenous researchers with whom they already have trusting relationships, they may seek out partnerships with researchers based on reputation and skillset, or they may choose to work with researchers who approach them with suggestions of potential funding options for mutually beneficial research. Indigenous leaders and groups use resultant research to articulate, reposition and assert their knowledge/s, values and interests in diverse fora including: development of collaborative resource management arrangements with government agencies (e.g., Zurba et al. 2019); to call for more rapid institutional change to support the inclusion of minority voices (e.g., Ojha et al. 2010; Armitage et al. 2011; Maclean et al. 2015); to assert their rights to ownership of their territorial country (e.g., Barber 2005; Chartier 2015); and to advocate their governance and on-ground management interests for ‘natural resources’ in their traditional territories (e.g., Maclean and BYB 2015; Pert et al 2015; Zurba et al 2019; Woodward et al. 2020).

Co-research partnerships signal an unsettling of the deep colonizing power dynamics that have been inherent in research ‘with’ Indigenous peoples (Hodge and Lester, 2005; Tobias et al. 2013; Castleden et al. 2017; Neale et al. 2019). Often, more traditional research practices have resulted in knowledge that reinforced western ontologies and epistemologies and silenced/repressed the voices and knowledges of the Indigenous peoples upon whom such research was focussed (Howitt and Jackson 1998; Smith 1999; Maclean 2015; Johnson et al. 2016). In response, a growing number of researchers (e.g., Smith 1999; Kovach 2010) call for decolonising and Indigenist approaches to define research agendas and supporting methodologies that challenge persisting colonial approaches to research (e.g. Howitt and Jackson 1998; de Leeuw et al. 2012). Growing scholarship into decolonising research methodologies (see Smith 1999; Johnson et al. 2016) has highlighted that one of the main challenges confronting researchers, in their efforts to operate effectively in this space, relates to Positionality (or Positionalities). Where ‘Positionality’ refers to the social, and political context that creates identity (e.g., race, gender, ability, and status). We add further detail to the category of ‘ability’ to include knowledge, skills, networks, and interests. With regards to research, Positionality traditionally refers to the powerful and privileged position that researchers often have Vis a Vis those whom they ‘research’. Effectively, researcher Positionality influences the collection, representation, and production of knowledge, and may reproduce inequalities and further disadvantage to project partners and their own communities (see Muhammad et al. 2015). To counter this, is the call for researchers to be cognisant of their ‘Positionality’ in any research engagement and to consider how it may influence their partners, knowledge (co-)creation and project outcomes. For example, Johnson et al. (2016:3) highlight “scientists have to learn to see our own privilege, our own context, our own deep colonizing. We have to learn to think anew…”.

We engage with these analytical themes to consider how the Positionality of all research partners influences the research processes, knowledge co-production, and the resultant project outcomes (are they considered usable knowledge by all partners?) The paper is set out in four parts. After a review of the literature on researcher Positionality, we provide the context for our case study (the Indigenous-led bush product sector in northern Australia) and an explanation of the methods used to co-author this paper. Next, we reflect on the role and power of ‘Positionality’ in research partnerships and projects. We draw insights from a project developed by the authors that aimed to create new knowledge to support the development of the Indigenous-led bush products sector in northern Australia (e.g., Maclean, Woodward et al. 2019; Jarvis et al. 2021). These reflections enable an interrogation of the politics of representation that confront researchers (and research partners). We use the four themes of Positionality defined by Wolf (1996) and augmented by Muhammad et al. (2015) to illuminate how the Positionality of each member of the project team influenced the processes and methods for knowledge co-production and ultimately the success of the research partnership. Our final analysis adds the category of usable knowledge to Wolf (1996) and Muhammad et al. (2015) themes of Positionality. This analysis sheds light on the empirical impacts that can result from research partnerships once a project has ended. The discussion provides an overview of the theoretical implications of this research for the Sustainability Science literature, and insights for sustainability science practitioners working in the Asia–Pacific region and Canada.

Literature review

Feminist sociologist Wolf (1996:2) discusses how the influence of researcher positionally is essentially to do with power. She conceptualises this power can be discernible in three inter-related dimensions. First, the power differences that stem from the different positionalities of the researcher and, in her words, the “researched’ (race, class, nationality, life changes, and urban–rural backgrounds)”. Second, the power that is exerted by the researcher during the research process, including in the definition of the research relationship, the potential unequal exchange between the researcher and the ‘researched’ and potential resultant exploitation. Third, she discusses the power exerted during writing and representation of the collected research data. Muhammad et al. (2015) draw on Wolf (1996) and add a fourth dimension to this conceptualisation: ‘the epistemology of power’—how power is exerted in the construction of knowledge (see Kuhn 1962; Foucault 1972). We add a fifth dimension: ‘the development of usable knowledge’—that focusses on how power is manifest in the usefulness of the knowledge outcomes of a project for all partners (e.g., Clark et al. 2016; Robinson et al. 2016). The remainder of this literature review takes these ‘inter-related dimensions of power’ to explore how they can be and are manifest in research. We return to these five dimensions in the discussion to consider the theoretical implications of our research for the sustainability science literature and the practical lessons for sustainability science practitioners working in the Asia–Pacific region, Canada, and elsewhere.

Positionality

Reflections on the influence of researchers’ Positionalities on the research process and outcomes can be found in many contexts including qualitative research (e.g., Berger 2013; Bourke 2014), sociology and gender studies (e.g., Wolf 1996), education (e.g., Merriam et al. 2001), and Indigenous-engaged research (e.g., Fisher 2015). Some scholars recognise the significance of Positionality, subjectivity, and reflexivity in the performance and governance of qualitative research (e.g., Fisher 2015; Pohl et al. 2010). Others reflect how insider/outsider ascribed and prescribed roles may influence the performance of (PAR) field work in developing country and cross-cultural contexts (e.g. England 1994; Fisher 2015; Kusek and Smiley 2014; Ozano and Khatri 2018; see also Merriam et al. 2001). Gender is discussed by feminist geographers as a direct influencer of research focus and data collection methods (e.g., Kusek and Smiley 2014). Some scholars highlight how the researcher’s values, motivations, and worldviews influence choice of research topic, location, and subsequent writings (e.g., Gold 2002). Others extend on the insider/outsider dichotomy to highlight multi-dimensional and complex range of research positionalities with a given community, including: indigenous-insider, indigenous-outsider, external-insider, and external-outsider (Banks 1998; Dwyer and Buckle 2009).

Some scholars provide textual and representational strategies to interrogate the politics of representation that confront researchers. This paper takes this one step further to provide strategies to enable a focus on the political practice of, empirical impacts from and theoretical learnings we can derive from illuminating the Positionality of all members of a given research partnership (see also Nagar and Ali 2003; Horlings, et al 2020). The very act of intentionally moving the focus away from the researcher to the research partners and the partnership itself can create the space to enable the priorities, subjectivities, and positionalities of all project partners for knowledge co-creation (c.f. Somerville and Turner 2020). For Indigenous partners, it also acknowledges the influence and primacy of connections to place, to country and to nation for project success (c.f. Somerville and Turner 2020; Suchet-Pearson et al 2013). It can result in shared research processes to set in motion multi-way learning, empowerment, and critical consciousness to “shift the research conversation altogether” (Muhammad et al. 2015:1050).

The research process

Wolf (1996) posits that one avenue through which power differentials emerge between the researcher and the researched is during the research process including via the definition of an unequal relationship that results in unequal exchange of knowledge and resources and can result in exploitation. Process-oriented, action, and collaborative research approaches (e.g., Johnson and Larsen 2013; Suchet-Pearson et al. 2013; Zurba et al. 2019), and Indigenist methodologies (e.g., Smith 1999) call researchers to question the positivist status of ‘researcher as observer’ (e.g., Hodge and Lester 2005), to move beyond the simple dichotomy of ‘researcher- researched’ and to effectively ‘work the hyphen’ (c.f. Fine 1994; Cunliffe and Karunanayake 2013). Researchers are called to explicitly share and devolve control of power by recognising research participants as knowledge partners. They are challenged to use strategies to empower partners to identify research objectives and/or desired outcomes (e.g., Woodward and McTaggart 2016) and be active in agenda setting and methodology selection (e.g., Maclean and Cullen, 2009; Zurba et al. 2019). Researchers are advised to spend time building trust with their partners including via paying attention to local protocols and cultural governance arrangements (Pohl et al. 2010; Woodward et al. 2020), co-development of transparent research governance arrangements, and involvement in all stages of the research process (Horlings et al. 2020). This paper extends this work by illuminating and embracing the Positionalities and related power dynamics that create research partnerships and showing how the intersection of Positionalities can determine project success.

Knowledge (co)creation and representation

Wolf (1996) discusses how researcher Positionality (and privilege) is also evident during writing and representation of the collected research data, if researchers hold tight to the representation of information. Muhammad et al. (2015:1049) add “the epistemology of power—how power is exerted in the construction of knowledge” as a further element that can be influenced by Positionality. Across academia scientific knowledge is still largely held aloft as superior to other knowledge forms and is often pitted in dichotomous binaries to local and Indigenous knowledges—which are rendered parochial and local (Weiss et al 2013; Maclean 2009; Jarvis et al 2020). This paradigm privileges scientific data collection, interpretation, and knowledge production, and ignores the Positionality of the knowledge makers. The seminal work of STS scholars (e.g., Haraway 1991; Harding, 1991; McDowell 1992) highlights that all knowledge is situated, tied to place and thus marked by its origins. These scholars critique the (scientific) knowledge production process that offers a ‘view from nowhere’, what Haraway (1991) calls the ‘God trick’, whereby much scientific knowledge and writing is separated from its origins and place of discovery and unreflective of the influence of power and Positionality.

Sustainability science practitioners are becoming cognisant of the influencers of Positionality and research processes in knowledge production, particularly in relation to working with Indigenous peoples and their worldviews (e.g., Johnson et al. 2016; Zanotti and Palomino-Schalscha 2016). Process-orientated approaches to research are considered by some sustainability science researchers as enablers for knowledge to be negotiated, defined, and co-produced with the aim of creating ‘spaces for societal learning’ (Wittmayer and Schakpe 2014). Early co-identification of research audiences can support appropriate framing of outputs; will be more likely to deliver greater impact by engaging with diverse audiences; and create alternate avenues for research partners to represent data, and key findings, through multiple lenses and voices (Nagar and Ali 2003). Such approaches can weave together diverse ways of knowing and understanding and can lead to other ways to conceptualise and manage issues of sustainability (Tengo et al. 2017). Approaches may include: ‘actionable knowledge’ (Kirchhoff et al. 2015), ‘working knowledge’ (Barber et al. 2014), ‘situated knowledge’ (Nygen, 1999), processes to enable ‘cultural hybridity’ (Maclean 2015), and ‘multiple evidence base’ approaches (Tengo et al. 2014). Processes that support knowledge co-production may result in local innovation and problem solving (e.g., Muhammad et al. 2015; Maclean and BYB 2015) and the ‘usable knowledge’ (e.g., Robinson et al. 2016) that is a central concept to sustainability science approaches and outcomes. As we will demonstrate in this paper, the Positionality of all research partners directly influences the kinds of processes that can be used to co-create knowledge, and the success of the resultant ‘usable’ knowledge.

Case study context and overview

The case study for this paper draws on insights from a research partnership between the authors of this paper (and two further partners) for a project that sought to design a Strategic Sector Development and Research Priority Framework to guide the strategic growth of the Indigenous-led Bush Products sector across northern Australia (see Woodward et al 2019; Maclean et al 2019). For the purposes of this paper, northern Australia is the region that lies north of Townsville in Queensland, and Broome, in Western Australia. It is a vast geographic area comprised of rich social and physical landscapes. It is home to many Indigenous Australians who actively look after their cultural and natural resources using diverse governance strategies suited to mixed land tenures and partnerships.

The Indigenous-led bush products’ sector incorporates a wide range of enterprises based on Australian native plant-derived industries including horticulture (seed harvesting for native plant nurseries, e.g., Girringun Biodiversity and Native Plant Nursery, see Maclean et al. 2020); the development of sustainable, alternative food (e.g., Gubinge/Kakadu plum powder and wafers manufactured by Kimberley Wild Gubinge—see KWG 2020); and botanical products (e.g., health and beauty products manufactured by Bush Medijinia 2020) for which there is a growing global demand (Pascoe 2014; Garnett et al. 2018; Gorman et al. 2019). Each of these types of enterprises results from the wild harvest, cultivation, and/or enrichment planting of select native plants. The sector continues to grow and diversify across northern Australia creating diverse opportunities and benefits to both Indigenous and non-indigenous Australians. In addition to providing direct economic benefits via the creation of jobs, incomes, and profits, the sector has supported significant social, cultural, and environmental returns including, for example, those generated from the ability to work on ancestral lands, build and share knowledge, and develop partnerships (Woodward et al. 2019).

Indigenous bush product enterprises face multiple challenges to the development of the sector. For example, geographic remoteness poses challenges for enterprises that have reduced access to: supply chains (e.g., Jarvis et al. 2021), workers and expertise (Venn 2007; Bodle et al. 2018), appropriate and adequate infrastructure (Flamsteed and Golding 2005; Cunningham et al. 2009; Shoebridge et al. 2012), and markets (posing particular challenges for perishable products (Cunningham et al. 2009). In addition, economic development narratives based on economic mainstreaming (anticipating that Indigenous people will move away from remote communities to regional centres for employment) fail to recognise the strength of Indigenous worldviews, culture, and remoteness as potential solutions for (rather than causes of) Indigenous disadvantage (e.g., Yates 2009; Bodle et al. 2018). [For example, with regards to the variety of ecosystem and public good services that can be provided by skilled Indigenous Rangers and other enterprises for the benefit of all Australians (e.g., Maclean et al. 2021)]. Furthermore, the lack of clear processes to protect Indigenous cultural and intellectual property, in the form of traditional plant knowledge (Robinson 2010; Robinson and Raven 2017; Robinson et al 2018), poses significant challenges to Indigenous communities and enterprises entering the market (see Spencer et al 2016; Woodward et al 2019; Jarvis et al. 2021, for details). Such competition has been seen to bring a suite of additional problems, including squeezing Indigenous people from the supply chain (e.g., Yates 2009), reducing opportunities for intergenerational transfer of Indigenous Knowledge (Walsh and Douglas 2011), and generating tensions due to trade-offs between maintaining traditional customs and exploiting species for economic gain (Walsh and Douglas 2011; White 2012). Despite these challenges, the sector continues to grow, creating diverse opportunities and benefits for Indigenous Australians, non-indigenous Australians, and products for the wider Australian and international community (e.g., KWB, 2020). Economic benefits (e.g., job creation, income, and profit) (Austin and Garnett 2011; Fleming 2015), social and cultural benefits (e.g., working on ancestral lands, knowledge sharing, and partnership development) (Austin and Garnett 2011; Davies et al. 2008; Holcombe et al. 2011), and environmental benefits resulting from improved land management (e.g., Garnett et al. 2018; Holcombe et al. 2011; Lingard and Martin. 2016).

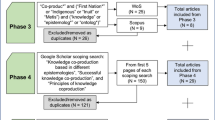

Our research project was designed to document these challenges via a scoping study and literature review (see Woodward et al. 2019; Jarvis et al. 2021), to identify potential barriers to sector growth, and to record opportunities for strategic growth of this sector. The barriers and opportunities were further identified in a project workshop collaboratively designed and delivered by the entire project team. The aim of the workshop was to bring together Indigenous leaders and enterprise owners of the emerging bush products sector in northern Australia (e.g., Bush Medijina, Kimberly Wild Gubinge, Yirriman Women Bush Enterprises) with the project team and other attendees, to share learnings and discuss future pathways for the sector (see Maclean et al. 2019a, b; c.f. Addison et al 2019). Importantly, the project team used a participatory action research approach (e.g., McTaggart 1997) to ensure that the project was co-designed and co-conducted by all project partners, and with significant input from Indigenous workshop participants brought together in Darwin in 2019 to discuss the aforementioned topics. The project team was comprised of Indigenous leaders and/or representatives, researchers, and an Industry representative, each wishing to use their skills to support Indigenous leadership of this sector.

-

Phil Rist, Nywaiygi Traditional Owner (TO) and Executive Officer of Girringun Aboriginal Corporation (Girringun), representative body of nine Traditional Owner groups from southern Queensland Wet Tropics/northern Dry Tropics. Girringun has a nascent bush products nursery that it wishes to development into a successful enterprise delivering co-benefits to the wider Girringun community (see Maclean et al 2020). Phil has worked with several researchers to develop projects to benefit the Girringun community, including research with Kirsten Maclean and colleagues (e.g., Maclean et al 2013a, b; Maclean et al 2020)

-

Dwayne Rowland, Indigenous Entrepreneur with family connections to the Tiwi people (Bathurst Island), the Jingili people (Daly Waters), and North-west Tasmania. Dwayne is co-owner of an Indigenous enterprise that uses Australian native plants as the basis for a range of botanical products.

-

Gerry Turpin, Mbabaram TO (northern Queensland) with family links to Wadjanburra Yidinjii and Ngadjon (Atherton Tablelands) and Kuku Thaypan (Cape York). Senior Ethnobotanist, Australian Tropical Herbarium, Queensland Herbarium, and Manager of the Tropical Indigenous Ethnobotany Centre (TIEC). Gerry has extensive research experience in northern Queensland with Indigenous people for which he was awarded the National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Island Award also called the ‘Deadly Award’ (see Queensland Government 2013). He is also co-leader of a recently awarded competitive grant from the Australian government with a focus on the Indigenous bush products sector (see Chapman et al 2020).

-

Kirsten Maclean, Senior Research Scientist with the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) (Brisbane) who has 15 years’ experience using participatory methodologies and qualitative participatory action research approaches with Indigenous Australians (and others) from northern Australia to develop projects focussed broadly on the role of knowledge, values, power and discourse in adaptive governance, enterprise development, and leadership of cultural and natural resource management (e.g. Hill et al 2015; Maclean 2009; Maclean et al 2013a, b; Maclean and Woodward 2013; Maclean and BYB, 2015; Pert et al 2015). She is committed to enable processes and structures within the research sector, and within research projects, for co-developed research, to acknowledge and protect Indigenous cultural and intellectual property and ensure benefit sharing from project process and outcomes.

-

Emma Woodward, Research Scientist (CSIRO) (Perth) has engaged and partnered in on-Country research with Australian Indigenous peoples for over 15 years. Prioritising Indigenous-led approaches, she supports the co-design of methods and tools to that reveal and enable Indigenous-led land and sea management and enterprise development, with the goal of advancing recognition and respect for Indigenous knowledge, governance, and decision-making in transdisciplinary contexts (see Woodward et al 2012; Liedloff et al 2013; Woodward and McTaggart 2019; Woodward et al. 2020).

-

Diane Jarvis, Academic, James Cook University (Cairns) (and joint CSIRO appointment until 2019) who has 5 years of research experience focusing on Indigenous natural resource management, and how these land management practices influence the well-being of the Indigenous Peoples of northern Australia (Jarvis et al 2018a, Jarvis et al 2018b, Addison et al 2019, Larson et al 2020, Pert et al 2020, Jarvis et al. 2020. She is committed to working in partnership with Indigenous Australians to co-develop research projects and co-produce and co-author research outputs, assisting benefits are shared with the Indigenous partners and increasing the opportunities for Indigenous voices to be heard and contribute to policy development.

We, the co-authors authorise the journal to publish our personal details and to link our names to the personal quotes/accounts shared in the results section. We consider this naming as essential to acknowledge how our individual positionalities influenced the research project. Equally important to note is that the team also included a representative from Kimberley Land Council (Broome) and one from the Australian Native Food and Botanicals (Coffs Harbour). We acknowledge their valuable input to the project and note that neither of them was in the position to contribute to this paper at the time of writing. Important to note is that Maclean and Rist had an established relationship, having conducted research together in the past (e.g., Maclean et al 2013a, b); Woodward and Turpin also had extensive co-research experience. Furthermore, the extensive experience of the project co-leaders (Maclean and Woodward) in facilitating participatory action research; the shared vision of the project team to realise beneficial outcomes for Indigenous peoples; and the experience of all team members both in working in diverse teams and developing research partnerships, helped ensure the project team faced very few challenges in their working relationship. This will not always be the case for research partnerships that often require a process of “forming, storming and establishment” of relationships, operating and knowledge sharing protocols and conflict resolution processes. However, we hope that by sharing our experiences here, others may learn how to approach, develop and establish proactive, equitable and lasting research partnerships.

Methods used to co-create this paper

This paper draws insights from the cross-cultural research partnership developed between the before mentioned project members. While research outcomes have been explored elsewhere (Maclean et al. 2019; Woodward et al. 2019; Jarvis et al. 2021) the role that the Positionality of each project member had to drive processes and methods for project governance, knowledge co-production and usable knowledge, has not been yet been considered. The methods used to co-author this paper reflect the reality that the non-CSIRO authors face multiple time-pressures in their daily work lives which means that contributing to scientific journals is not a priority. It also recognises that the CSIRO authors have a personal and institutional expectation to reflect on and publish research outcomes in scientific journals. Given these expectations and the specific research skill set (e.g., research analytics, literature reviewing, conducting interviews, data analysis, and journal publication writing skills), it is reasonable that the CSIRO researchers took the lead to manage and write the paper. Some researchers might consider this, apparently unbalanced, approach to authorship a questionable process in realising co-authorship with Indigenous project partners. However, the CSIRO authors, being aware of the very real impact of positionality on personal interest to write scientific papers, drew on their prior co-authorship experiences, and problem-solving skills to negotiate a pathway to suit all project partners. The CSIRO researchers designed a set of questions to enable all co-authors to reflect on how their Positionality influenced the project. ‘Positionality’ was defined as ‘what you bring to the table, the hats you wear’. Questions corresponded to the analytical themes of this paper (see Appendix A). Given the aforementioned life priorities (where journal paper writing isn’t near the top of the list) and time constraints faced by the non-CSIRO project partners, it was necessary to allow several months for co-authors to respond to the questions. Indeed, two of the project members were not in the position to contribute their responses due to other more pressing priorities. Eventually, non-CSIRO team members documented their responses via email or telephone discussion. The lead authors collated themes (see Appendix B) and selected the quotes that are used in the following section to bring the multiple voices of the co-authors into the paper (c.f. Woodward and Marrfurra McTaggart, 2016). Co-authors were asked to check and improve the resultant text. This was done via textual documentation via email and/or telephone discussions.

Results

In this section, we extend the literature on Positionality by discussing the insights from our analysis. We consider how Positionality influenced the research partnership and process, knowledge co-creation and representation (writing), and post-project impacts (also see Appendix B). In the Discussion, we articulate how these insights can inform how sustainability scientists, Indigenous leaders, and others can develop better partnerships in future, contributing to better research outcomes and ensuring appropriate sharing of the benefits.

Positionality and partnerships

Here, we share general reflections on our personal Positionality. These reflections illuminate the complex range of Positionalities that exist between all project members (see Appendix B for detail). It shows how each individual's Positionality, although complementary, is equally distinct and multi-dimensional within and between group typologies (e.g., female researchers, Indigenous leaders). This brought a rich mix of knowledge and skills (e.g., research skills, business acumen, Indigenous knowledge, and supply-chain knowledge), interests (e.g., to facilitate Indigenous-led research, create opportunities in bush products), and networks (e.g., Indigenous, CSIRO, business, international) to the project. It created and facilitated a research partnership that benefited all. These reflections illuminate how the research partnership is a performance of these Positionalities in combination and, as will be explored below, the post-project benefits are the result of this unique intersection of Positionalities.

Each project member reflected on their personal responsibility to the unique research partnership by discussing their interests and obligations to make a difference for Indigenous Australians (see Appendix B). To Phil, Executive Officer of Girringun, this responsibility equated to an obligation to share resulting co-developed knowledge with his Indigenous networks:

“[…] it’s almost an obligation to share those findings for all Aboriginal and Torres Strait people. Some might be in the position to take up that information.”

Dwayne, an Indigenous Entrepreneur, explained how the project enabled him to share his business acumen and networks with Indigenous Australians working toward economic independence:

“I wanted to be involved to help create life changing opportunities for Indigenous people [who are] using the knowledge of the native flora handed down for hundreds of generations”.

For Gerry, an Ethnobotanist, the project represented a way to extend his work at the Tropical Indigenous Ethnobotany Centre (see TIEC, 2020), and create on-ground action:

“I thought there may be on-ground opportunities for TO groups to be able to identify plants which they could use for financial benefits.”

Emma, articulated how, as a researcher this responsibility can include drawing on one’s potential position of power and privilege, in this case from within a national research organisation that attracts significant funding; has government influence; and a reputation for delivering world-class research:

“I see my role… as enabling others’ values, interests, perspectives and knowledge that are often marginalised in decision-making processes.”

Respectively, Diane and Kirsten expressed their responsibility to use their research skills, networks and position at CSIRO to “improve life and wellbeing of [Indigenous] Australians” and to “make a difference for Indigenous Australians”. Each of the CSIRO (non-indigenous) researchers work with their colleagues to develop research projects that are co-developed and led, as appropriate, with Indigenous leaders. The aim of such projects is for the co-development of useable knowledge for the benefit of all research partners. They use their privileged position within their research organisation to advocate, develop, and use research structures (e.g., Indigenous Steering Committees, research agreements) and processes (e.g., participatory action research, co-leadership as appropriate) to progress decolonising research approaches within the research sector (e.g., this Special Feature of Sustainability Science). They share their experiences and learnings within their research organisation (e.g., organisation-wide webinars, Indigenous Futures initiatives), at international conferences, in their academic and practitioner publications (e.g., Maclean and Cullen 2009; Zurba et al. 2019; Woodward et al. 2020) and they are often asked by their national and international peers for advice on such topics. Sometimes, they are confronted with challenging questions from Indigenous people with regards to why they work in this area given they are not themselves Indigenous. This highlights the tension they might feel as non-indigenous people who use and advocate decolonising research methodologies to work for change within the research sector that has been (and in many instances continues to be) a colonial institution. Whenever possible and as appropriate, they seek to co-author research reports and journal papers with their Indigenous partners, so that Indigenous voices might directly challenge colonial constructs (e.g., Maclean and Bana Yarralji Bubu Inc., 2015; Addison et al 2019; Woodward, and Marrfurra McTaggart 2019; Larson et al 2020).

This work extends Gold (2002) by illuminating how the Positionality of researchers and Indigenous leaders/partners influences choice of research topic, location and resultant writing (see below). It also shows how Positionality influences choice of research partner(s). This is an important observation given that co-research approaches are dependent upon Indigenous leaders choosing to work with researchers and vice versa. Phil’s words illuminate the complex inter-play between individual Positionalities and partnership success:

“I think that your involvement and personality and who you are as a person [Kirsten] really helped me to be involved as well, to be effective in that participation […] for me personally, that was a big plus, your understanding of how busy I am […] if you get the wrong person who doesn’t understand that kind of thing, that can cause difficulties but because of you and your involvement it worked.”

This observation highlights the complexity of the power differentials between members of co-research partnerships aimed at supporting and enabling Indigenous-led research agendas.

Research process

Our research shows, by example, how power sharing processes can enable genuine research partnerships and can work to confront what Wolf (1996) described as the power inequalities exerted by researchers (on the ‘researched’) during the research process. To be effective, power sharing processes need to explicitly articulate the role and responsibility of each project member (according to their Positionality) for successful decision-making and project governance. Furthermore, as illuminated in Phil’s words above, processes need to be flexible and adaptable to the unique Positionality and circumstances of each project member.

Each team member reflected on their choice in roles and responsibilities for project governance and decision-making (see Appendix B). It is clear that the Positionalities of project members determined their interest (or not) to be active in certain project governance arrangements (e.g., set-up, guidance, and management). For example, the project (co)leaders (Kirsten and Emma) practiced a leadership approach to enable their Positionalities to benefit Indigenous Australians. Kirsten explained:

“from the outset it was important to use an approach to enable ethical and inclusive governance and decision-making processes. In this way we could ensure - through guidance from all project partners – that the project would result in maximum benefits for all (e.g. project partners, Indigenous communities)”

Gerry, Phil, and Dwayne chose to be active members of one such governance process, the Indigenous Steering Committee (Committee). It was the partial responsibility of the Committee to ensure the project used culturally appropriate approaches and methods, focussed on the information needs of Indigenous Australians involved in the bush products’ sector, and would generate benefits for Indigenous communities. A formal document was drawn up to articulate these roles and responsibilities, and the related roles of the CSIRO researchers. This included formal recognition for the protection of IP, including Indigenous cultural and intellectual property.

Quotes from Gerry, Phil, and Dwayne illuminate how their Positionalities influenced their role on the Committee. Gerry articulated his role was “to ensure things were done in the right way, ethics and Intellectual Property were discussed”. Phil explained that he was there as “a TO, a Girringun representative and a knowledge seeker”. Furthermore, Dwayne’s words reflect both his enthusiasm to be involved in the Committee (and project) and how he felt that this formal governance process supported and enabled his voice and leadership “I was honoured to participate in multiple roles and felt incredibly valued by the CSIRO team”.

Important to note is how the Committee also supported and enabled the interests and skills of the CSIRO researchers. For example, it supported Emma and Kirsten to broker interactions with the Research co-funders on their behalf (e.g., information sharing; project management). Given their Positionality, Kirsten and Emma had the institutional support, were paid for their time (whereas project partners provided in-kind time) and had a personal interest to develop networks with the co-funders. The members of the Committee were happy to step back from such interactions and enable Kirsten and Emma to take this role. Importantly, the CSIRO researchers also used their influence and position of working within a reputable national research institution to ensure the project would and could have processes in place to acknowledge and protect ICIP, and to ensure ethical process and outcomes with regards to the release of any project findings.

Reflections also highlighted the influence of external challenges (e.g., funding) on the potential impacts of the project partnership (see Appendix B). Project members felt that additional funding for a multi-year project (as was requested in the initial project expression of interest that included up to 3 pilot studies) would have resulted in much greater social impact and research application. Gerry’s words highlight the tension and mismatch between his Positionality (including interest in on-ground action) and what could be described as the position taken by the funding body with regards to managing funding for competing project budgets:

“Everything was done as well as possible with the funding available, but obviously with more funding, everything can be done better... I think I’ve had enough with just talking about it. In future applications, I would like to see more on ground stuff…. I would have liked a pilot project to happen in some communities.”

This tension was also articulated by Dwayne, passionate to support Indigenous economic development, who felt that the social impact of the project was curtailed by funding decisions: “the small amount of funding received [seemed almost tokenistic] especially in comparison to other projects that had a far smaller social impact and received considerably more”. The CSIRO researchers, who advocate that Indigenous leadership should be acknowledge by payment for their time, although appreciative for the opportunity, also felt conflicted about the available funding. This tension also highlights the ongoing negotiation that all project partners had to undertake with regards to their decision to engage with the project (or not). For example, Emma’s words articulate the personal conflict she felt that resulted from mismatched Positionalities:

“I did question whether we should have accepted the significantly smaller project scope [and funding] as we were not able to pay the Steering Committee for their participation and contributions.”

Development of usable knowledge?

Our interrogation of how Positionality influences the success of research partnerships culminates with a focus on the outcomes and benefits derived by project partner, since the project ended. This expose provides a window into the ongoing influence of the project partnership beyond project completion. The following reflections show the extent to which each project member chose, or chose not, to use the project outcomes. In effect, it provides an evaluation of sorts of the success of the project partnership to deliver outcomes that would benefit all and not just the CSIRO researchers (cf. Wolf, 1996; Muhammad et al 2015). In particular, it considers whether the outcomes resulted in ‘usable knowledge’ that each project partners has since used for ongoing benefit and success. These outcomes highlight how projects that are designed to recognise and take advantage of the different Positionalities of project members, can provide strategies to move beyond the power imbalances that exist between ‘the researchers and the researched’ (Wolf, 1996). Reflections shared below also illustrate the link between individual Positionality, usable knowledge, and derived benefits.

Phil discussed the benefits that were accrued to Traditional Owners during the research project, and since it ended. First, the project provided space for Elders’ views and opinions to be recognised and respected:

“One of the most positive [things] is the involvement of Elders and others, provided an avenue for them to speak […] Their advice was sought after by the researchers […] I’ve seen Elders transformed from an inward sort of person to become vocal and engaged, their self-esteem and self-worth has been improved”

Next, Phil explained how this project provided the groundwork and impetus for Girringun to co-develop a second project focussed on development options for the Girringun native plant nursery (see Maclean et al 2020). The resultant research and networks have been instrumental to current discussions that Girringun is facilitating with others in the bush products value chain in far north Queensland. He articulated:

“The conversations that we are having now with those players are a direct result of the two projects that we were involved with. As we scratch the surface, we can expose who we need to develop more partnerships with as we go along […we have developed some] capacity to really capitalise on those opportunities […] the information is there, and from that perspective, those two projects that we were involved with were extremely important. We are now trying to get the timing right and weave the collaboration stuff, so can look for funding and a proposal to capitalise.”

Kirsten also highlighted the follow-on project with Girringun (see Maclean et al 2020) as a post-project benefit, as well as having the opportunity to provide exposure to the Indigenous-led bush products sector via speaking opportunities in Australia, New Zealand, and Asia. She was also open about the professional benefits that she personally gained from the project:

“Meeting new people and extending networks with Indigenous leaders, within CSIRO, the University of New South Wales, the funding body, learning about the bush products sector from Indigenous leaders, and professional development experience including developing project (co)-leadership skills”

Dwayne also enthused about how much he enjoyed the project as an opportunity to build networks with like-minded people from different professional and practitioner worlds. Indeed, he has already developed project ideas with others he met for the first time during the project “I have made life-long connections that will be invaluable to me beyond this project”. In a similar vein, Gerry modestly explained how he has since used the outcomes “for information for other bush tucker projects fund applications with various partners”—including a prestigious 5 year Australian Research Council Grant into Indigenous Bushfoods Technology (see Chapman et al 2020).Footnote 1 Diane also discussed how she has already used “new skills and knowledge […to inform] a different project rural/remote Indigenous groups in Northern Australia”. Emma also enjoyed extending her networks with Indigenous leaders working in the bush products space and reported “being invigorated by…seeing the diverse efforts and experiences Indigenous groups have in building enterprises”. These reflections highlight the multiple post-project benefits accrued by all project partners. They illuminate the reality that although the resultant usable knowledge constitutes written documentation, it also extends beyond the written word to include new connections, relationships, networks, partnerships, and skills. All of which have enabled new opportunities for each project member separately, and in concert.

Knowledge co-creation and Representation

Our combined reflections bring focus to the powerful role that each project member can have for knowledge co-creation (research focus, conduct, data collection, and analysis) and representation (write-up). The project concept and design represent the intersection of the project members’ Positionalities. Personal decisions to join the project team were reinforced by the reality that the project was co-designed. The project concept and design were the result of the combined knowledge, interests, skills, and self-proclaimed responsibilities of the project partners. The process of knowledge co-creation was further reinforced by the aforementioned inclusive approach to project governance that aimed to create spaces for diverse voices and knowledges. This approach recognises that the partnership process is as equally important as the outcomes. It was further supported by a formal document drawn up to protect the intellectual property of all partners, and to share resultant project intellectual property.

Project partners had equal power to determine the research focus within the limits/bounds of project resourcing (research to support the Indigenous bush products sector), conduct (literature review, workshop), and to write-up the findings (representation). How partners contributed was influenced by their Positionalities (skills, interests, networks, and knowledge). The CSIRO researchers became aware of the project funding call via their research networks. They drew on their Indigenous networks (via telephone calls) to gauge interest and seek guidance to develop an expression of interest (EOI) focussed on the Indigenous bush products sector. Given their skills and institutional support, the CSIRO researchers drafted the EOI from these discussions, and the Indigenous partners edited and improved the EOI as appropriate. Indigenous leadership was clearly evident in the EOI, a fact applauded by the project co-funders, and a determining factor in the EOI being selected as one of only 16 projects to be funded from a pool of 115 EOI.

Indigenous partners advised on culturally appropriate approaches for data collection (local case studies, workshops, and face-to-face meetings) and the kinds of knowledge and outputs to support ongoing Indigenous livelihood development in the bush products industry. The CSIRO researchers led and developed the literature review (see Woodward et al 2019) with advice from project partners. Indigenous partners influenced the workshop design, conduct, and data collection process as illuminated here. Gerry explained that he was “a participant, gave a presentation and also co-facilitated the workshop”. He was in fact a key player in the design and conduct of the workshop. He drew on his extensive network to suggest workshop participants; he presented a session drawing on his ethnobotany expertise; and he brought his experience in workshop facilitation and engendered calm and patience among workshop participants. Importantly, he insisted there be a session on Indigenous cultural and intellectual property (ICIP) and the bush product industry. It resulted in extensive discussion regarding the challenges of identifying ICIP within and between Traditional Owner groups as well protecting ICIP from national and international prospectors.

Dwayne modestly expressed how he contributed to the project concept, workshop design and conduct, and literature review “as required and added my feedback when asked […] I was thrilled to be one of the presenters at the workshop and able to review the reports prior to their release”. In reality, he was instrumental in expanding the focus of the workshop beyond Australia by suggesting his Shanghai-based Australian colleague be invited to contribute to the workshop. Dwayne co-designed and presented the resultant workshop session that illustrated the larger opportunities for Indigenous leaders and communities involved in the bush products sector.

Phil was active in the workshop co-conduct both as a co-presenter about the Girringun native plant nursery (see Maclean et al 2020) and linked ‘bush tucker to plate’ school-based education program (Clarke 2019). He was an active participant who highlighted the essential role of bush product sector governance structures that are culturally appropriate, and work to protect Indigenous cultural and intellectual property of native plants and their health properties.

The CSIRO researchers collected and collated workshop data into a closed-access report co-authored by all participants (see Maclean et al 2019) and were instrumental in producing all written materials (e.g., emails, literature review, workshop report, and final project report). As already highlighted above and will be explored further in the discussion, the role that each project member took with regards to the representation of the co-produced knowledge was directly influenced by their Positionality (skills, interests, responsibilities, and knowledge).

Discussion and conclusion

In this paper, we explored how Positionality influenced the development and completion of a project in support of the development of the Indigenous-led bush products sector in northern Australia. The role of Positionality in influencing each team members’ engagement/experience in knowledge co-creation, knowledge representation (writing), and realisation of post-project benefits were assessed based on their own reflections of their contributions and engagement. Here, we articulate how insights derived from this analysis might inform future research processes by sustainability scientists, Indigenous leaders, and others, to develop better partnerships and contribute to more beneficial research outcomes for all partners.

Researchers are called to be cognisant of their ‘Positionality’ in any research engagement and to consider how it may influence their partners, knowledge (co-)creation, and project outcomes. At the same time, a growing number of researchers call for decolonising and Indigenist approaches to research that challenging persistent colonial research and knowledge creation processes. There remains scant literature that interrogates how the Positionality of research partners (e.g., Indigenous, industry) and research partnerships (involving researchers, Indigenous leaders, industry representatives, and others) also influence project processes, knowledge (co)creation, and representation. This paper has provided one such interrogation by actively moving the sole focus away from the researcher to also consider the Positionality of the research partners and the partnership itself. In doing so, we have created the space to understand how the priorities, subjectivities, and Positionalities of all project partners can and do influence the research process, knowledge co-creation, and the development of usable knowledge.

Theoretically, this research extends that of Wolf (1996) and Muhammad et al (2015) in two ways. First, we add a further dimension to their combined conceptualisation of the power exerted by researchers on ‘the researched’. Wolf (1996) contends that the power imbalances can be discerned by the researcher Positionality vis a vis that of the ‘researched’, during the research process and in the writing and representation of knowledge. Muhammad et al. (2015) add a further dimension to this conceptualisation—the epistemology of power. We add a fifth dimension to consider the power dynamics evident in the development of usable knowledge—which can be best understood via evidence of benefits resulting from the project once it has ended (i.e., post-product benefits). Perhaps more significantly, we turn the focus of the four dimensions of power (identified by Wolf (1996) and Muhammad et al. (2015) away from the researcher (and their Positionality) to consider the power of all research partners who together constitute the research partnership.

Our conceptualisation of Positionality highlights the power of each of the research partners to influence the project. It shows the vital role of each members’ Positionality to augment the power of the partnership itself (via skills, networks, knowledge, and positions of power and influence). Furthermore, it provides a way for other researchers/research partners to better understand the power dynamics, the multiple subjectivities, the priorities and interests of all project partners, and the potential opportunities that may evolve from the partnership and resultant usable knowledge. We show by example how any research partnership is a performance of these Positionalities in combination, and how the post-project benefits (which may include the development of usable knowledge) are the result of this unique intersection of Positionalities. This conceptualisation will be of use for Sustainability Science as it provides a way for scientists, practitioners, and research partners, to consider the power that each project member (not just the scientists) brings to a project (c.f. Johnson et al 2016) and to make use of the unique Positionalities of each member to influence project processes, knowledge co-production, and the development of usable knowledge. It also illuminates how an interrogation of post-project benefits and legacies (e.g., usable knowledge) can enable a better understanding of the lasting success of a project and the partnership.

This research also provides several practical insights useful for Sustainability Science practitioners working in the Asia–Pacific region, Canada, and elsewhere. We group these insights here with regards to partnership development; strategies to better enable power sharing during the research process; and the challenges and opportunities for knowledge co-production for the development of usable knowledge. Each of these insights, strategies, and observations is grounded in the recognition that the Positionality of each research partner may influence how and when they choose to be involved in project partnerships, research design, and knowledge creation. As such, it is essential to create spaces and approaches that recognise and respect this reality.

We assert that researchers who choose to partner with Indigenous leaders and others have an important ethical and moral role to play in ensuring their practices unsettle colonial research constructs and engage with decolonising methodologies (Zanotti and Palomino-Schalscha 2016). Such partnerships can be formed through relationships which seek mutually beneficial outcomes and opportunity for Indigenous leadership (de Leeuw et al. 2012; Woodward and McTaggart 2016; Castleden et al. 2012; Woodward et al. 2020). Working toward such new approaches necessitates researchers to reflect upon the influence of their Positionality within such engagements. This is particularly the case for researchers who seek process-oriented research approaches, such as action research, to create and support spaces for reflexive learning and whom aim to “put sustainability into action” (Wittmayer and Schapke, 2014:483). Furthermore, researchers may have several roles within research partnerships, including reflective scientist, process facilitator, knowledge broker, change agent, self-reflexive scientist (Wittmayer and Schapke, 2014; Horlings et al 2020; Woodward and McTaggart 2016), and boundary agent (Zurba et al 2019). More effective partnerships may be defined where they create space for supporting local governance and cultural protocols (e.g., Woodward et al. 2020); cultural hybridity (Maclean 2015); enable social and political transformation (Smith 1999; Johnson et al 2016); and plural co-existence (e.g. Howitt and Suchet-Pearson 2003; 2006; Zanotti and Palomino-Schalscha 2016). Ineffective partnerships may perpetuate colonial research processes based on knowledge extraction and subjugation, misinterpretation, and misrepresentation of minority voices.

Equally, Indigenous leaders and others who choose to develop partnerships with researchers have important and different roles to play to empower each unique partnership. For example, Indigenous leaders may need to guide the partnerships to ensure that the research adopts processes to protect Indigenous cultural and intellectual property (Maclean and BYB, 2015; Woodward et al. 2020; Zurba et al 2019), and can progress at a pace that enables culturally appropriate engagement and decision-making. Such processes may include guidance on the selection of appropriate methodologies, involvement of the ‘right’ people (socially, culturally, politically), and discussions to ensure the research generates benefits for their communities.

Researchers can explicitly share power in the research process by recognising the role of each project member as a knowledge partner who, rightly, can identify their own research objectives and/or desired outcomes (Woodward and McTaggart 2016). Such research partnerships draw on the varied skills and strengths of all partners to co-design, co-conduct, co-govern, and co-author a research project(s). Participatory research methods can be used to build mutual respect and trust; two-way knowledge exchange, and knowledge co-production (Johnson et al. 2016; Woodward and Marrfurra McTaggart 2016). Strategies can ensure that time is spent in the early stages of the research process for relationship building and to enable trust to grow. For example, action research approaches demand that the researcher shares agenda setting and methodology selection with others and this trust-building period provides a foundation for the co-implementation of transparent research governance arrangements and identification of opportunities for participation at all stages of the research process, including joint reflection. Furthermore, attention to local protocols, including cultural governance arrangements, can be partially respected by building flexibility into research plans, to better accommodate partner interests, and allow research progression at a pace that enables meaningful inclusion.

Formal processes can be used to ensure diverse knowledges inform knowledge co-production. They can include formal knowledge sharing agreements, for example to recognise Indigenous cultural and intellectual property rights, and respect for multiple goals of the knowledge co-production (for example opportunities for the intergenerational transfer of Indigenous knowledge throughout the project). Resources can be allocated to recognise the knowledge and time contributions of all project members (not formally paid by their institution to conduct research). Researchers can facilitate the co-authorship of publications to ensure that diverse interpretations and reflections are included (Woodward and McTaggart 2016). Attention must be given to effective methods and processes for engaging diverse voices, perspectives, and ways of engaging in dialogue, to ensure the writing process is accessible to those that wish to be included. Important to note, is that while research team members value the writing of scientific papers, non-research team members may not see the application or use of such publications in their own contexts. However, as was the case with this co-authored paper, some non-research team members may see the value in contributing their reflections via a dialogical process or may not prioritise such writing at all. Rather, they may prefer to develop other kinds of knowledge artefacts that, equally, may not be a priority for research team members.

Trust is paramount to research writing and representation. This may become evident in the writing process where some co-authors may not actively engage in the written representation of the research (e.g., in a report) but wish to be named as co-author or contributor. This highlights the interesting tension between individual Positionalities and original choice to join a project team. Some non-research partners will trust the researchers to represent the research on their behalf, possibly because of the Positionality of the researcher(s), that may include a proven track record that has resulted in mutual trust.

Trust is equally central to the development of usable knowledge, during and post-project benefits. The value of usable knowledge (project outputs) is shown when project members share outcomes inform new project proposals and to strengthen networks. Importantly, usable knowledge may not only include co-authored reports, papers, and presentations. It may also include other knowledge artefacts including the unwritten ideas and knowledge that are co-developed during a project. Such unwritten knowledge also equates to post-project benefits as it may empower the individual to develop new networks and relationships for future collaborations that extend the co-produced and ‘usable’ knowledge (c.f. Nagar and Ali 2003). Equally, unwritten, intangible project processes and approaches may generate immediate benefits to the wider community including building of self-esteem, strengthening of cultural pride and well-being. Such outcomes, although not typically acknowledged in formal processes, are directly connected to the Positionality of project members whose interests in research may also extend to community well-being.

Notes

The Grant success rate—for projects to commence in 2021—was 37.5%. This project was one of the nine projects funded from a total pool of 24 applicants (see ARC 2020).

References

Addison J, Stoeckl N, Larson S, Jarvis D, Esparon M, Bidan Aboriginal Corporation, Bunuba Dawangarri Aboriginal Corporation RNTBC, Ewamian Aboriginal Corporation RNTBC, Gooniyandi Aboriginal Corporation RNTBC, Yanunijarra Ngurrara Aboriginal Corporation RNTBC (2019) The ability of community based natural resource management to contribute to development as freedom and the role of access. World Dev 120:91–104

ARC (2020) Australian Research Council. Selection report: discovery indigenous 2021. https://www.arc.gov.au/grants/grant-outcomes/selection-outcome-reports/selection-report-discovery-indigenous-2021. Accessed 9 Dec 2020

Armitage DF, Berkes F, Dale A, Kocho-Schellenberg E, Patton E (2011) Co-management and the coproduction of knowledge: Learning to adapt in Canada’s Arctic. Glob Environ Chang 21:995–1004

Austin BJ, Garnett ST (2011) Indigenous wildlife enterprise: Mustering swamp buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) in Northern Australia. J Enterp Communities 5(4):309–323. https://doi.org/10.1108/17506201111177343

Banks JA (1998) The lives and values of researchers: implications for educating citizens in a multicultural society. Edu Res 27(7):4–17

Barber M (2005) Where the clouds stand: Australian aboriginal relationships to water, place, and the Marine environment in Blue Mud Bay, Northern Territory, Unpublished PhD Thesis. The Australian National University, Canberra. https://doi.org/10.25911/5d78da14735de

Barber M, Jackson S, Shellberg J, Sinnamon V (2014) Working Knowledge: characterising collective indigenous, scientific, and local knowledge about the ecology, hydrology and geomorphology of Oriners Station, Cape York Peninsula, Australia. Rangel J 36(1):53–66. https://doi.org/10.1071/RJ13083

Berger R (2013) Now I see it, now I don’t: researcher’s position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qual Res 15(2):219–234. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794112468475

Bodle K, Brimble M, Weaven S, Frazer L, Blue L (2018) Critical success factors in managing sustainable indigenous businesses in Australia. Pac Account Rev 30(1):35–51

Bourke B (2014) Positionality: reflecting on the research process. Qual Rep 19(33):1–9

Medijina B (2020) Collections. https://bushmedijina.com.au/collections. Accessed 13 Nov 2020

Castleden H, Morgan VS, Lamb C (2012) “I spent the first year drinking tea”: Exploring Canadian university researchers’ perspectives on community-based participatory research involving Indigenous peoples. Can Geo 56:160–179

Castleden HE, Martin D, Cunsolo A, Harper S, Hart C, Sylvestre P, Stefanelli R, Day L, Lauridsen K (2017) Implementing indigenous and western knowledge systems (Part 2): ‘you have to take a backseat’ and abandon the arrogance of expertise. IIPJ. https://doi.org/10.18584/iipj.2017.8.4.8

Chapman D, Fitzgerald M, Schmidt S, Fredericks B, Bryceson K, Cave R, Ross H (2020) Project IN210100039, scheme round statistics for approved proposals: Discovery Indigenous 2021 Round 1. https://rms.arc.gov.au/RMS/Report/Download/Report/1b0c8b2e-7bb0-4f2d-8f52-ad207cfbb41d/212. Accessed 9 Dec 2020

Chartier C (2015) Partnerships between aboriginal organizations and academics. IIPJ. https://doi.org/10.18584/iipj.2015.6.2.9

Clark WC, van Kerkhoff L, Lebel L, Gallopin GC (2016) Crafting usable knowledge for sustainable development. Proc Natl Acad Sci 113(17):4570–4578. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1601266113

Clarke C (2019) Building relationships through food, fully booked—celebrating women in food and drinks. https://www.fullybookedwomen.com/voices/tag/Voices. Accessed 13 Nov 2020

Coombes B, Johnson JT, Howitt R (2014) Indigenous geographies III: Methodological innovation and the unsettling of participatory research. Prog Hum Geogr 38:845–854

Cunliffe AL, Karunanayake G (2013) Working within hyphen-spaces in ethnographic research: Implications for research identities and practice. Organ Res Method 16:364–392

Cunningham AB, Garnett S, Gorman J, Courtenay K, Boehme D (2009) Eco-Enterprises and Terminalia ferdinandiana: “Best Laid Plans” and Australian Policy Lessons. Econ Bot 63:16–28

Davies J, White J, Wright A, Maru Y, LaFlamme M (2008) Applying the sustainable livelihoods approach in Australian desert Aboriginal development. Rangel J 30(1):55–65. https://doi.org/10.1071/RJ07038

de Leeuw S, Cameron ES, Greenwood ML (2012) Participatory and community-based research, Indigenous geographies, and the spaces of friendship: a critical engagement. Can Geogr 56:180–194

Dwyer SC, Buckle JL (2009) The space between: on being an insider-outsider in qualitative research. Int J Qual Methods 8(1):54–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690900800105

England KVL (1994) Getting personal: reflexivity, positionality, and feminist research. Prof Geogr 46(1):80–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0033-0124.1994.00080.x

Fermantez K (2013) Rocking the boat: Indigenous geographies at home in Hawai’i. In: Johnson JT, Larsen SC (eds) A deeper sense of place: stories and journeys of collaboration in Indigenous research. Oregon State University Press, Corvallis, pp 103–124

Fine M (1994) Working the hyphens: reinventing self and other in qualitative research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS (eds) Handbook of qualitative research. Sage Publications Inc, pp 70–82

Fisher KT (2015) Positionality, subjectivity, and race in transnational and transcultural geographical research. Gend Place Cult 22(4):456–473. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2013.879097

Flamsteed K, Golding B (2005) Learning through indigenous business: the role of vocational education and training in indigenous enterprise and community development. National Centre for Vocational Education Research (NCVER)

Fleming AE (2015) Improving business investment confidence in culture-aligned indigenous economies in remote Australian communities: a business support framework to better inform government programs. IIPJ 6(3):5

Foucault M (1972) The archaeology of knowledge. Tavistock Publications Ltd, London

Garnett ST, Burgess ND, Fa JE, Fernández-Llamazares Á, Molnár Z, Robinson CJ, Watson JEM, Zander KK, Austin B, Brondizio ES, Collier NF, Duncan T, Ellis E, Geyle H, Jackson MV, Jonas H, Malmer P, McGowan B, Sivongxay A, Leiper I (2018) A spatial overview of the global importance of Indigenous lands for conservation. Nature Sustainability 1:369–374

Gold L (2002) Positionality, worldview and geographical research: a personal account of a research journey. Ethics Place Environ 5(3):223–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/1366879022000041588

Gorman JT, Wurm PAS, Vemuri S, Brady C, Sultanbawa Y (2019) Kakadu Plum (Terminalia ferdinandiana) as a sustainable indigenous agribusiness. Econ Bot. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12231-019-09479-8

Haraway D (1991) Simians, cyborgs and women. Routledge, London

Hill R, Davies J, Bohnet IC, Robinson CJ, Maclean K, Pert PL (2015) Collaboration mobilises institutions with scale-dependent comparative advantage in landscape-scale biodiversity conservation. Environ Sci Policy 51:267–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2015.04.014

Holcombe S, Yates P, Walsh F (2011) Reinforcing alternative economies: Self-motivated work by central Anmatyerr people to sell Katyerr (Desert raisin, Bush tomato) in central Australia. Rangel J 33(3):255–265. https://doi.org/10.1071/RJ10081

Horlings LG, Nieto-Romero M, Pisters S, Soini K (2020) Operationalising transformative sustainability science through place-based research: the role of researchers. Sustain Sci 15(2):467–484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-019-00757-x

Howitt R, Jackson S (1998) Some things do change: Indigenous rights, geographers and geography in Australia. Aust Geogr 29(2):155–173

Howitt R, Suchet-Pearson S (2003) Spaces of knowledge: Ontological pluralism in contested cultural landscapes. In: Anderson K, Domosh M, Pile S, Thrift N (eds) Handbook of Cultural Geography. Sage Publications, London

Howitt R, Suchet-Pearson S (2006) Rethinking the building blocks: ontological pluralism and the idea of ‘management’’.’ Geografiska Annaler: Series b, Human Geogr 88(3):323–335

Jarvis D, Maclean K, Woodward E (2021) The Australian Indigenous-led bush products sector: insights from the literature and recommendations for the future. Ambio. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-021-01542-w

Jarvis D, Stoeckl N, Addison J, Larson S, Hill R, Pert P, Watkin Lui F (2018a) Are Indigenous land and sea management programs a pathway to Indigenous economic independence? Rangel J 40(4):415–429. https://doi.org/10.1071/RJ18051

Jarvis D, Stoeckl N, Hill R, Pert P (2018b) Indigenous land and sea management programs: can they promote regional development and help “close the (income) gap”? Aust J Soc Issues 53(3):283–303. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajs4.44

Jarvis D, Stoeckl N, Larson S, Grainger D, Addison J, Larson A (2021) The learning generated through Indigenous natural resources management programs increases quality of life for Indigenous people—improving numerous contributors to wellbeing. Ecol Econ 180:106899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2020.106899

Johnson JT, Larsen SC (eds) (2013) A deeper sense of place: stories and journeys of collaboration in indigenous research. Oregon State University Press, Corvallis

Johnson JT, Cant G, Howitt R, Peters E (2007) Creating anti-colonial geographies: Embracing Indigenous peoples’ knowledges and rights. Geogr Res 45:117–120

Johnson JT, Howitt R, Cajete G, Berkes F, Louis RP, Kliskey A (2016) Weaving Indigenous and sustainability sciences to diversify our methods. Sustain Sci 11:1–11

Kirchhoff CJ, Esselman R, Brown D (2015) Boundary organizations to boundary chains: Prospects for advancing climate science application. Clim Risk Manag 9:20–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2015.04.001

Kovach M (2010) Conversational Method in Indigenous Research. First Peoples Child Fam Rev 5(1):40–48

Kuhn TS (1962) The structure of scientific revolutions. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Kusek WA, Smiley SL (2014) Navigating the city: gender and positionality in cultural geography research. J Cult Geogr 31(2):152–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/08873631.2014.906852

KWG (2020) Kimberly Wild Gubinge. The Product. https://www.kimberleywildgubinge.com.au/product. Accessed 13 Nov 2020

Larson S, Stoeckl N, Jarvis D, Addison J, Grainger D, Watkin Lui F, Walalakoo Aboriginal Corporation , Bunuba Dawangarri Aboriginal Corporation RNTBC , Ewamian Aboriginal Corporation RNTBC, Yanunijarra Aboriginal Corporation RNTBC (2020) Indigenous land and sea management programs (ILSMPs) enhance the wellbeing of indigenous Australians. IJERPH 17(1):125. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17010125

Liedloff AC, Woodward EL, Harrington G, Jackson S (2013) Integrating indigenous ecological and scientific hydro-geological knowledge using a Bayesian network in the context of water resource development. J Hydrol 499:177–187

Lingard K, Martin P (2016) Strategies to support the interests of aboriginal and Torres strait islander peoples in the commercial development of gourmet bush food products. Int J Cult Prop 23(1):33–70. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0940739116000023

Maclean K (2009) Reconceptualising desert landscapes: unpacking historical narratives and contemporary realities for sustainable livelihood development in Central Australia. GeoJournal 74(5):451–463

Maclean K (2015) Cultural Hybridity and the Environment. Strategies to celebrate local and indigenous knowledge. Springer, Singapore

Maclean K, Cullen L (2009) Research methodologies for the co-production of knowledge for environmental management in Australia. J R Soc N Z 39(4):205–208

Maclean K, Bana Yarralji Bubu Inc (2015) Crossing cultural boundaries: integrating indigenous water knowledge into water governance through co-research in the Queensland wet tropics. Australia. Geoforum 59:142–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.12.008

Maclean K, Woodward E (2013) Photovoice evaluated: an appropriate visual methodology for aboriginal water resource research. Geogr Res 51(1):94–105

Maclean K, Robinson C, Bock E, Rist P (2021) Reconciling risk and responsibility on Indigenous country: bridging the boundaries to guide knowledge sharing for cross-cultural biosecurity risk management in northern Australia. J Cult Geogr. https://doi.org/10.1080/08873631.2021.1911078

Maclean K, Cuthill M, Ross H (2013a) Six attributes of social resilience. J Environ Planning Manage 57(1):144–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2013.763774

Maclean K, Ross H, Cuthill M, Rist P (2013b) Healthy country, healthy people: an Australian Aboriginal organisation’s adaptive governance to enhance its social–ecological system. Geoforum 45:94–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2012.10.005

Maclean K, Robinson CJ, Natcher DC (2015) Consensus building or constructive conflict? Aboriginal discursive strategies to enhance participation in natural resource management in Australia and Canada. Soc Nat Resour 28(2):197–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2014.928396

Maclean K, Woodward E, Jarvis D, Rowland D, Rist P, Turpin G, Martin P, Glover R (2019) A strategic sector development and research priority framework for the traditional owner-led bush products sector in northern Australia CSIRO, Australia. Accessed at https://publications.csiro.au/rpr/download?pid=csiro:EP193300&dsid=DS1. Accessed 19 May 2021

Maclean K, Rassip W, Rist P (2020) Girringun Aboriginal Corporation future development aspirations for the Girringun native plant nursery. CSIRO, Australia

McDowell L (1992) Valid games? A response to Erica Schoenberger. Prof Geogr 44:212–215

McTaggart R (ed) (1997) Participatory action research: international contexts and consequences. State University of New York Press, Albany, New York