Abstract

Background

Experts estimate virtual urgent care programs could replace approximately 20% of current emergency department visits. In the absence of widespread quality guidance to programs or quality reporting from these programs, little is known about the state of virtual urgent care quality monitoring initiatives.

Objective

We sought to characterize ongoing quality monitoring initiatives among virtual urgent care programs.

Approach

Semi-structured interviews of virtual health and health system leaders were conducted using a pilot-tested interview guide to assess quality metrics captured related to care effectiveness and equity as well as programs’ motivations for and barriers to quality measurement. We classified quality metrics according to the National Quality Forum Telehealth Measurement Framework. We developed a codebook from interview transcripts for qualitative analysis to classify motivations for and barriers to quality measurement.

Key Results

We contacted 13 individuals, and ultimately interviewed eight (response rate, 61.5%), representing eight unique virtual urgent care programs at primarily academic (6/8) and urban institutions (5/8). Most programs used quality metrics related to clinical and operational effectiveness (7/8). Only one program reported measuring a metric related to equity. Limited resources were most commonly cited by participants (6/8) as a barrier to quality monitoring.

Conclusions

We identified variation in quality measurement use and content by virtual urgent care programs. With the rapid growth in this approach to care delivery, more work is needed to identify optimal quality metrics. A standardized approach to quality measurement will be key to identifying variation in care and help focus quality improvement by virtual urgent care programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Virtual urgent care, also referred to as tele-urgent care and direct-to-consumer telehealth, has expanded rapidly in recent years.1,2,3,4 Virtual urgent care visits offer a convenient and timely care option for many patients and hold potential in diverting an estimated 20% of emergency department (ED) visits.5,6,7 However, studies evaluating the impact of virtual urgent care programs on quality of care have been mixed to date. One study found virtual urgent care likely improves access to care for some patient populations but could lead to increased utilization and healthcare expenditures.8 Another study found similar guideline-concordant antibiotic management between brick-and-mortar urgent care clinic visits and virtual urgent care visits, but a higher frequency of follow-up visits after virtual urgent care appointments.9 Prior work evaluating virtual urgent care programs found significant variation in quality between provider groups in caring for acute illnesses.10 Despite this described variation, there is lack of consensus on measurement of quality to evaluate these programs.11 Likewise, there is limited reporting of quality metrics in virtual urgent care by regulatory organizations and professional medical societies.12

Standardizing key quality measures for virtual urgent care is a critical action in advancing patient outcomes and care model operations. Metrics can help guide benchmarks of high- and low-performing programs, inform effective resource utilization, and identify opportunities for quality improvement. However, existing quality measures relevant to virtual urgent care are limited. Although a natural starting point for identifying optimal quality metrics for use in the virtual urgent care setting might be measures used by brick-and-mortar urgent care, this setting unfortunately also lacks widely developed metrics from which to take direction.13 Moreover, the relevance of quality measures proposed by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) is limited for virtual urgent care encounters.14

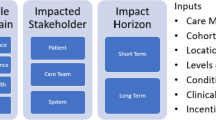

To guide virtual urgent care programs and other applications of telehealth in quality metric development, the National Quality Forum (NQF) has developed quality frameworks which promote a focus on measuring impact in five key domains: access to care, financial impact/cost, experience, effectiveness, and equity.15,16 Prior evaluation of the implementation of telehealth quality metrics among telehealth programs revealed variation between programs in domains in which metrics were developed.17 However, to our knowledge no studies have described the use of quality metrics across virtual urgent care programs. We sought to characterize use of quality measures related to effectiveness and equity by virtual urgent care programs. We selected these domains given a wide variation described within effectiveness quality measurement subdomains in our prior work as well as the recent strong renewed interest in digital health equity.17,18 Additionally, by focusing on two domains, we could better allow for adequate time to capture all relevant metrics. By describing implementation of quality metrics within these domains, attention and resources may be dedicated more urgently to areas of quality that are “under-measured.” As a secondary aim, we sought to understand programs’ motivations for and barriers to quality measure development to better inform possible future strategies for implementing and benchmarking quality metrics for virtual urgent care.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

This was a qualitative study of eight virtual urgent care programs. We defined virtual urgent care as care provided by a remote clinician to a patient, addressing acute, unscheduled care needs. Virtual urgent care offerings may involve one or multiple options for patients to connect with a clinician, including telephonic, video-conferencing, and asynchronous chat.19 In an attempt to triage appropriate patients, most virtual urgent care offerings ask patients to select a chief complaint from a list of appropriate chief complaints prior to scheduling a visit. Virtual urgent care offerings may then ask patients to queue in a virtual waiting room to see the next-available provider or offer an appointment time in the near-future (i.e., next 1–4 h). Increasingly, virtual urgent care programs are seeking opportunities to improve clinical efficiency by initiating visits using asynchronous texts to help triage patient complaints.20 We conducted semi-structured interviews with telehealth medical directors and health system leaders of virtual urgent care programs from July to October 2022 (Table 1).

The study team interviewers (DW, KL, EH, TJ, KZ) were composed of five practicing emergency physicians with training in qualitative research and expertise in telehealth research. Three had experience providing emergency medicine telehealth, including one emergency medicine telehealth medical director. The study was reviewed and considered exempt by the Mass General Brigham’s Institutional Review Board.

Participant Selection

We used a convenience sample of virtual urgent care program representatives identified through a review of the virtual urgent care literature and through relationships with members of the study team. A research librarian aided the team in developing a PubMed query to identify published literature on virtual urgent care programs. Articles and their references were reviewed to build a target list of programs. The study team then identified contact information from published articles and online queries. Email invitations to participate were sent to potential participants. Follow-up invitations were sent a maximum of two times. We ultimately interviewed eight representatives from eight unique virtual urgent care programs and did not pursue further additional interviews given that thematic saturation was achieved.

Interview Guide Development and Interviews

All team members participated in the development of the interview guide. We structured the questions to mirror the effectiveness and equity quality domains of the NQF Framework.15,16 The interview guide was then pilot tested with two former virtual urgent care leaders at two different institutions and revised to incorporate their feedback.

The interview started with introductions by the team and study participants, followed by obtaining verbal study consent. We then queried participants about relevant quality metrics captured by their program. Motivations for quality measurement as well as barriers to quality measurement were also explored. Interviews were 45 to 60 minutes long and were conducted on Microsoft Teams by a minimum of two members of the study team. Interview transcripts were created using the Microsoft Teams transcription function and field notes were collected during the interviews. The transcripts were not returned to the participants for comments, and the participants did not provide feedback on the findings. Repeat interviews were not conducted.

Analysis

Quality measures reported by participating programs were identified by coding interview transcripts and interview notes. Measures were then grouped according to the NQF’s effectiveness domain and subdomains (system effectiveness; clinical effectiveness; operational effectiveness; and technical effectiveness) as well as equity domain. We used a grounded theory approach for thematic analysis. Four members of the study team (DCW, KL, KSZ, TJ) reviewed interview transcripts, independently developed a codebook with one level of themes, and categorized transcript comments related to motivations for and barriers to quality measurement. Coding discrepancies were adjudicated as needed by additional team members. Feedback on study findings was not provided by study participants.

RESULTS

We emailed study invitations to 13 representatives at 13 unique virtual urgent care programs, received responses from 11 representatives and interviewed eight virtual urgent care leaders from eight unique programs (Table 1). Of the three representatives who responded and were not interviewed, one indicated that their institution no longer provided a virtual urgent care offering and two were unable to be scheduled for an interview. Programs represented were predominantly academic health systems (6/8) and situated in urban areas (5/8). All programs offered video visits with a clinician (8/8) and a majority offered audio-only visits (5/8). Most programs (6/8) delivered more than 1,000 total virtual urgent care visits per month.

Most virtual urgent care programs (7/8) interviewed reported measuring at least one quality metric within the NQF’s effectiveness domain (Table 2). Programs were most likely to measure a quality metric related to clinical effectiveness (7/8) (i.e., antibiotic rates for sinusitis at the physician level or virtual urgent care visit within 7 days for same chief complaint) as well as operational effectiveness (7/8) (i.e., Left Without Being Seen rate). Quality metrics related to technical effectiveness (i.e., video failure rate) were measured by half of the programs interviewed. Only one program reported measuring a quality metric related to equity of care, examining virtual urgent care use by zip code.

Most study participants reported a desire to ensure quality of care (6/8) as a motivation for quality measurement (Table 3). For example, participant 3, from a large, private telehealth company offering virtual urgent care services mentioned an interest “to ensure providers are performing high quality care.” Additionally, a medical director of virtual health at an urban, academic health system mentioned “a desire to prove that we’re delivering the same quality of care via telemedicine that we are in person.” Demonstrating the value of the virtual urgent care offering was the second most cited motivation (4/8) for measuring quality. Most participants cited demonstrating value to internal stakeholders (i.e., health system chief financial officer) with one participant noting that an anticipation of insurance reimbursement requirements prompted quality metric development.

Limited resources for quality measurement were most commonly (6/8) reported as being a barrier to quality measurement. Specifically, analytic resources for development, implementation, and upkeep of quality metrics were cited in addition to limited bandwidth amongst existing virtual urgent care administrative staff. Participant 1, a medical director of an academic, virtual urgent care program in the west, highlighted that “dedicated analytic resources to support virtual health initiatives is very difficult.” Moreover, a clinical innovation leader at an urban, academic program in the northeast reported that “limited bandwidth amongst staff makes quality measurement challenging.” Lack of standardization, including lack of quality metric guidance and opaque electronic medical record (EMR) data definitions, was the second most cited (3/8) barrier to quality measurement.

DISCUSSION

In summary, most virtual urgent care programs represented in this sample capture quality metrics related to the NQF’s domain of effectiveness, particularly within the subdomains of clinical and operational effectiveness. In contrast, only one of the eight programs in our sample currently uses a quality measure related to health equity. Programs expressed high levels of motivation to measure quality of care delivery, with the most cited motivations being a desire to ensure quality of care and to demonstrate the value of their program. Limited resource availability served as a significant barrier to quality measurement for many programs, specifically lack of data analytic support.

We found significant variation in quality measurement content related to effectiveness among the virtual urgent care programs in our study. This is similar to our prior work examining quality measurement among a broad spectrum of telehealth programs.17 Most programs reported measuring at least one aspect of clinical and operational effectiveness, but a minority reported quality measures within the subdomain of system effectiveness, which describes the ability of virtual urgent care to assist in coordinating care across settings and between clinicians. Lack of quality monitoring in the system effectiveness domain may contribute to the increased healthcare utilization after virtual urgent care visits described by prior studies.9 With the anticipated growth of virtual urgent care visits, including virtual urgent care models that may include Mobile Integrated Health paramedics, there is an increasingly pressing need to understand current quality of care evaluation to inform potential standardization of quality metrics as well as to allow for benchmarking and focused quality improvement interventions.

Despite the increasing recognition of the importance of equity in healthcare delivery, we found only one of the virtual urgent care programs in our study reported tracking an equity-related quality measure. This underscores the need for standardization in quality reporting. Virtual urgent care represents a significant opportunity to narrow healthcare disparity in access to care if implemented well; however, at the same time, these programs could further exacerbate healthcare inequities given historic barriers of technology access, language accessibility, and internet access for people with lower socioeconomic status and people of color.21,21,22,23,25 Investment and regulatory changes have sought to improve equitable access to virtual urgent care services.26,26,28 Encouragingly, a recent study evaluating demographic shifts in virtual urgent care visits after recent COVID-19 telehealth expansion policies has noted increasing proportions of vulnerable patient populations (e.g., elderly, uninsured, rural populations) using virtual urgent care.29 However, future sunsetting of these policies with the end of the public health emergency puts these equity-related gains in virtual urgent care access at risk.30 Development and implementation of standard equity measures could provide much-needed feedback and benchmarking for institutions to inform further maturation and adoption of local telehealth-equity related initiatives such as investment in digital connectivity and digital literacy in addition to multiple-language offerings. A few health systems, which did not participate in our study, have published their own telehealth quality frameworks which emphasize equity; however, the degree to which and how institutions are actively monitoring the equity of their telehealth programs is relatively unknown.31

While the virtual urgent care programs we interviewed are strongly motivated to develop and implement quality measurement, resource and technology limitations remain a significant barrier. This is unsurprising given prior work finding quality measurement initiatives to be costly; one study from 2016 estimated the cost to be $40,069 per physician per year.32 A root cause of this high cost is likely the explosion of quality metrics in recent decades with less attention paid by regulatory and quality institutions to date to the cost of implementing and reporting quality measures.33 Participants in our study mentioned lack of standardization, in particular how electronic medical record data is labeled, and how quality metrics are defined, as a major barrier to quality metric development and use. Limited usability of EMR data has been widely reported in the literature and efforts to structure and define data are in the works.34,35 Improving healthcare data usability may represent an underutilized lever to drive down the cost of quality measurement for virtual urgent care programs as poorly labeled and structured data can increase workloads for quality analytics teams. Additionally, development of measures that are readily extracted from EMR data without requiring “hands-on” abstraction will be key. To our knowledge, our study is the first to report on challenges faced by virtual urgent care quality metric initiatives.

The findings from our study could inform several key next steps for virtual urgent care quality metric development. First, further work, research, and leadership should focus on developing, validating, and standardizing virtual urgent care quality metrics related to effectiveness and equity. Clearly defined metrics would help virtual urgent care program leaders monitor and benchmark performance. CMS could develop quality metrics for virtual urgent care and consider tying the most clinically relevant measures to reimbursement, especially given the Congressional Budget Office’s recent estimate that extending pandemic related telehealth measures could increase Medicare costs by $25 billion over 10 years.36 As research informs the most relevant quality metrics for implementation, medical professional societies such as the American College of Physicians and American College of Emergency Physicians could further develop guidelines for virtual urgent care to reduce variation in care.37,38 As with all measure development processes, pilots should occur first before mandated adoption to limit unintended consequences and understand the variation in performance and cost of measurement.39 Initial focus on a few validated and actionable metrics as opposed to a multitude will allow programs to invest in quality improvement activities and limit unnecessary implementation and reporting costs, a major barrier to quality metric use found in our study.40 At the same time, efforts to allow for easy sharing of quality measurement best practices between programs as well as advocacy for improved EMR quality reporting capabilities to alleviate burdensome resource costs could unlock even more virtual urgent care quality improvement opportunities.

This study has multiple limitations. The first is that we used a convenience sampling method, identifying tele-urgent care programs from the published literature and through professional networks. Programs represented therefore tended to be established and relatively mature (87.5%, > 2 years) with larger patient volumes, potentially allowing for more investment in quality measurement infrastructure. Quality metric use and key themes identified may then not be representative of nascent virtual urgent care programs; and thus, our sample is likely biased toward more developed programs with more robust quality measurement processes. Additionally, most programs (~ 75%) interviewed were based at academic institutions where the desire to evaluate and publish the impact of virtual urgent care on quality of care may have influenced broader quality metric implementation than in a community health system or commercial setting. Furthermore, as the majority of programs participating were based in urban areas with widespread broadband penetration, they may be less motivated than rural-serving virtual urgent care programs to measure equity measures related to connectivity. Lastly, some participants had pre-established relationships with the study team which could have contributed to responses influenced by social desirability bias.

In conclusion, our research furthers understanding of virtual urgent care programs’ use of quality metrics related to effectiveness and equity as well as identifies common barriers to implementation and motivation for quality measurement. Given the potential large role virtual urgent care could play in delivering equitable and effective care, more work should focus on developing, evaluating, and standardizing quality metrics. To ensure maximal impact as well as program sustainability, particular attention to financial and human resource requirement needs for quality metric collection and reporting should be given as this was identified as a major barrier to current quality metric use.

Data Availability

The participants of this study did not give written consent for their data to be shared publicly, so due to the sensitive nature of the research supporting data is not available.

References

Koziatek CA, Rubin A, Lakdawala V, et al. Assessing the Impact of a Rapidly Scaled Virtual Urgent Care in New York City During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Emerg Med. 2020;59(4):610-618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2020.06.041.

Lovell T, Albritton J, Dalto J, et al. Virtual vs traditional care settings for low-acuity urgent conditions: An economic analysis of cost and utilization using claims data. J Telemed and Telecare. 2019;27(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633x19861232.

Schwamm LH, Erksine A, Licurse A. A digital embrace to blunt the curve of COVID19 pandemic. Npj Digit Med. 2020;3(64). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-020-0279-6.

Uscher-Pines L, Sousa J, Mehrotra A, et al. Rising to the challenges of the pandemic: Telehealth innovations in U.S. emergency departments. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021 28(9):1910–1918. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocab092.

Khairat S, Lin X, Liu S et al. Evaluation of Patient Experience During Virtual and In-Person Urgent Care Visits: Time and Cost Analysis. J Patient Exp. 2021;8. https://doi.org/10.1177/2374373520981487.

Weinick RM, Burns RM, Mehrotra A. Many emergency department visits could be managed at urgent care centers and retail clinics. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:1630-6. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0748.

Bestsennyy O, Gilbert G, Harris A, Rost J. Telehealth: A quarter-trillion-dollar post-COVID-19 reality? McKinsey and Company. July 2021. Available at: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare/our-insights/telehealth-a-quarter-trillion-dollar-post-covid-19-reality. Accessed January 15, 2023.

Ashwood JS, Mehrotra A, Cowling D, et al. Direct-To-Consumer Telehealth May Increase Access To Care But Does Not Decrease Spending. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(3):485-491. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1130.

Shi Z, Mehrotra A, Gidengil CA, et al. Quality Of Care For Acute Respiratory Infections During Direct-To-Consumer Telemedicine Visits For Adults. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018 37(12):2014-2023. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05091.

Schoenfeld AJ, Davies JM, Marafino BJ et al. Variation in Quality of Urgent Health Care Provided During Commercial Virtual Visits. JAMA Intern Med. 2016; 176(5):635-642. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.8248.

Ghosh T, Gupta K, Branagan L, et al. Defining Quality in Telehealth: An Urgent Pandemic Priority. Managed Healthcare Executive. October 2020. Available at: https://www.managedhealthcareexecutive.com/view/defining-quality-in-telehealth-an-urgent-pandemic-priority. Accessed April 21, 2023.

Hayden EM, Davis C, Clark S, et al. Society for Academic Emergency Medicine 2020 Consensus Conference. Telehealth in emergency medicine: A consensus conference to map the intersection of telehealth and emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2021;28(12):1452–1474. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.14330.

Shipley N. National Urgent Care Clinical Quality Metrics: ‘This is the way’. The Journal of Urgent Care Medicine. Available at: https://www.jucm.com/national-uc-clinical-quality-metrics/. Accessed: March 13, 2023.

Telehealth Guidance for Electronic Clinical Quality Measures (eCQMs) for Eligible Professional/Eligible Clinician 2022 Quality Reporting. Available at: https://ecqi.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/2022-EP-EC-Telehealth-Guidance.pdf. Accessed: April 6, 2023.

Creating a framework to support measure development for telehealth. National Quality Forum. August 2017. Available at: https://www.qualityforum.org/publications/2017/08/creating_a_framework_to_support_measure_development_for_telehealth.aspx. Accessed March 13, 2023.

Rural telehealth and healthcare system readiness measurement framework – final report. Rural Telehealth. National Quality Forum. November 2021. Available at: https://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2021/11/Rural_Telehealth_and_Healthcare_System_Readiness_Measurement_Framework_-_Final_Report.aspx. Accessed March 13, 2023.

Whitehead DC, Jaffe T, Hayden E, et al. Qualitative Evaluation of Quality Measurement within Emergency Clinician-Staffed Telehealth Programs. Ann Emerg Med. 2022;80(5): 401-407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2022.05.026.

Lyles CR, Wachter RM, Sarkar U. Focusing on Digital Health Equity. JAMA. 2021; 326(18):1795-1796. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.18459.

Shah BR, Schulman K. Do Not Let A Good Crisis Go to Waste: Health Care’s Path Forward with Virtual Care. NEJM Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery. 2021. Available from: https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0693 . Accessed 30 May 2023.

Lignel O. Asynchronous virtual health: 3 reasons it’s critical for now and foundational for the future. MedCity News. October 2020. Available at: https://medcitynews.com/2020/10/asynchronous-virtual-health-3-reasons-its-critical-for-now-and-foundationalfor-the-future/. Accessed 13 March, 2023.

Samuels-Kalow M, Jaffe T, Zachrison K. Digital disparities: designing telemedicine systems with a health equity aim. Emerg Med J. 2021;38:474-476. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2020-210896.

Velasquez D, Mehrotra A. Ensuring the growth of telehealth during COVID-19 does not exacerbate disparities in care. Health Affairs Blog 2020. Available at: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20200505.591306/full/ . Accessed 20 April, 2023.

Roberts ET, Mehrotra A. Assessment of disparities in digital access among Medicare beneficiaries and implications for telemedicine. JAMA Intern Med, 2020;180:1386. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2666.

Walker DM, Hefner JL, Fareed N, et al. Exploring the digital divide: age and race disparities in use of an inpatient portal. Telemed J E Health. 2020;26:603–613. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2019.0065.

Goodman CW, Brett AS. Accessibility of Virtual Visits for Urgent Care Among US Hospitals: a Descriptive Analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36, 2184-85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-05888-x.

Severin C, Curry M. Telehealth Funding: Transforming Primary Care And Achieving Digital Health Equity For Underresourced Populations. Health Affairs Blog. September 2021. Available at: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20210908.121951/ . Last accessed 21 April 2023.

USDA Invests $42 Million in Distance Learning and Telemedicine Infrastructure to Improve Education and Health Outcomes. U.S. Department of Agriculture. February 2021. Available at: https://www.usda.gov/media/press-releases/2021/02/25/usda-invests-42-million-distance-learning-and-telemedicine. Accessed 21 April 2023.

Connecting Americans to Health Care. Federal Communications Commission. Available at: https://www.fcc.gov/connecting-americans-health-care. Accessed 21 April 2023.

Khairat S, Yao Y, Coleman C, et al. Changes in Patient Characteristics and Practice Outcomes of a Tele-Urgent Care Clinic Pre- and Post-COVID19 Telehealth Policy Expansions. Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2022:19(Spring):1k.

Telehealth policy changes after the COVID-19 public health emergency. Health Resources & Services Administration. February 2023. Available at: https://telehealth.hhs.gov/providers/policy-changes-during-the-covid-19-public-health-emergency/policy-changes-after-the-covid-19-public-health-emergency. Accessed 21 April 2023.

Demaerschalk BM, Hollander JE, Krupinski E et al. Quality Frameworks for Virtual Care: Expert Panel Recommendations. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2023;7(1): 31-44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2022.12.001.

Casalino LP, Gans D, Weber R, et al. US Physician Practices Spend More Than $15.4 Billion Annually to Report Quality Measures. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(3). https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1258.

Schuster MA, Onorato SE, Meltzer DO. Measuring the Cost of Quality Measurement: A Missing Link in Quality Strategy. JAMA. 2017;318(13): 1219-1220. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.11525.

Ebbers T, Kool RB, Smeele LE, et al. The Impact of Structured and Standardized Documentation on Documentation Quality; a Multicenter, Retrospective Study. J Med Syst. 2022; 46(7):46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-022-01837-9.

Cohen DJ, Dorr DA, Knierim K, et al. Primary Care Practices’ Abilities And Challenges in Using Electronic Health Record Data For Quality Improvement. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018; 37(4). https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1254.

Fiscal Considerations for the Future of Telehealth. 2022. Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. Available at: https://www.crfb.org/papers/fiscal-considerations-future-telehealth. Accessed 13 April 2023.

Herzer KR, Pronovost PJ. Ensuring Quality in the Era of Virtual Care. JAMA. 2021;325(5):429-430. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.24955.

Qaseem A, MacLean CH, Tierney S, et al. Performance Measures for Physicians Providing Clinical Care Using Telemedicine: A Position Paper From the American College of Physicians. Ann of Intern Med. 2023. https://doi.org/10.7326/m23-0140.

Lester HE, Hannon KL, Campbell CM. Identifying unintended consequences of quality indicators: a qualitative study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(12):1057-1061. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs.2010.048371.

Dunlap NE, Ballard DJ, Cherry RA, et al. Observations from the Field: Reporting Quality Metrics in Health Care. National Academy of Medicine. 2016. Available at: https://nam.edu/observations-from-the-field-reporting-quality-metrics-in-health-care/. Accessed 21 April 2021.

Acknowledgements:

Grant support was provided through a Mass General Brigham Centers of Excellence Research Grant.

Funding

Mass General Brigham Centers of Excellence Research Grant

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest:

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Whitehead, D.C., Li, K.Y., Hayden, E. et al. Evaluating the Quality of Virtual Urgent Care: Barriers, Motivations, and Implementation of Quality Measures. J GEN INTERN MED 39, 731–738 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-024-08636-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-024-08636-7