Abstract

Background

Health information exchanges (HIEs) have proliferated over the last decade, but a gap remains in our understanding of their benefits to patients and the healthcare system. In this systematic review, we provide an updated report on what is known regarding the impacts of HIE on clinical, health care utilization, and cost outcomes in the adult inpatient setting.

Methods

We searched Pubmed, Web of Science, Embase, Cochrane, and Ebsco databases for citations published between January 2015 and August 2021. Eligible studies were English-language experimental or observational studies. We assessed risk of bias via the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute’s Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies.

Results

We identified 11 eligible studies—1 quasi-experimental and 10 observational. Five studies examined readmission rates and 3 found benefits from HIE. Three studies examined mortality with 2 finding benefits from the availability of HIE. Eight studies examined utilization and cost outcomes with 2 finding benefits from HIE, 1 finding poorer outcomes with HIE, and the others finding no impact.

Conclusions

Evidence for the impacts of HIE remains largely observational with little direct measure of HIE use during clinical care, making causality difficult to assess. The highly variable outcomes examined by these studies limit meaningful synthesis. The strength of evidence is low that HIE reduces unplanned readmissions and mortality and there is insufficient evidence for the impact of HIE on cost or utilization. The increased number of studies specific to inpatient settings that examine objective outcomes with more rigorous statistical methods is a promising development since prior reviews.

Trial Registration

PROSPERO 2021 CRD42021274049 Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42021274049

Amendments to Protocol

Initially planned use of the Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale was substituted for the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute’s Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies as it was better suited to evaluate the primarily retrospective observational cohort studies identified in the review.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

BACKGROUND

Health information exchange (HIE) involves the electronic transfer of health information between health care organizations according to nationally recognized standards.1 The passage of the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act of 2009 provided $14–$27 billion for electronic health record (EHR) adoption that included a goal of national HIE.2 The Medicare and Medicaid EHR Incentive Program stage 1 objectives also included requirements for EHR interoperability with a goal of improved efficiency and quality.3 The Medicare Access and Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2015 and other federal policies have encouraged the continued adoption of HIE by providers, hospitals, and health systems.4 Despite these substantial federal investments, the return on investment of HIE has not yet been well demonstrated in the literature.5 The impact of HIE on outcomes in the inpatient setting in particular has not been previously reviewed.

There have been prior systematic reviews evaluating the impact of the adoption of HIE after the passage of the HITECH Act. A 2011 review found 5 relevant studies—only 2 of which included inpatient data—that examined outcomes from HIE interventions, with small or inconsistent benefits.6 An updated 2014 review found only 2 studies examining the effects of HIE in the inpatient setting—one study found no difference in hospital readmission rates and the other found a positive association between HIE implementation and patient satisfaction.7 There were significantly more studies by 2015 when a review was published by Hersh et al.8, but these 24 studies were conducted in multiple care settings, and none examined clinical outcomes or harms—rather, they reported uncertain reductions in healthcare utilization and costs.8 The most recent review examining work published in 2010 through 2017 reported a growing body of research evaluating HIE but again included studies from outpatient, emergency, and inpatient settings without a clear picture of the specific impact on inpatient outcomes.9

Since the publication of the studies examined by these reviews, there has been a significant increase in the use of HIE in the inpatient setting.10,11,12,13,14 By 2021, 86% of general acute care hospitals or 3006 facilities had adopted electronic health records meeting criteria for certification by the Office of the National Coordinator for health information technology, including the capability to electronically exchange health information.15 We seek to provide an updated report on the state of what is known regarding the impacts of HIE use specifically in the adult inpatient setting. By limiting the review to a single setting of care, we may be able to better clarify the impact of HIE. We particularly seek to update the 2014 Hersh review to summarize what might be known about the clinical impact of HIE in addition to the previously studied health care utilization and cost outcomes.

METHODS

Data Sources and Searches

A systematic review protocol was developed and registered in PROSPERO.16 A clinical informationist developed the search in PubMed which was then peer-reviewed by a second clinical informationist. The search was then translated to PubMed, Cochrane Database, Embase, Web of Science, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, ProQuest Dissertations, and Theses Global (see Appendix 3 for technical search strategies). The search was supplemented by a review of references of eligible studies. Studies of hospitalized, inpatient adults published between January 2015 to August 2021 were included, and pediatric or animal studies were excluded.

Study Selection

English language studies were included that compared the presence versus absence of HIEs in adult inpatient care settings. Comparisons could be between institutions with and without HIEs or before and after HIE implementation in single systems. Studies set exclusively in emergency or ambulatory care settings were excluded. Included studies could be randomized control trials or observational studies, but not modelling experiments, case series, or case reports. We included studies that examined clinical, economic, or population outcomes as primary or secondary outcomes but excluded studies that examined HIE impacts only on research or other non-clinical effects (e.g., user experience). Two investigators independently evaluated each study for eligibility. Disagreement was resolved by consensus after discussion.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Searches were uploaded in EndNote with an initial deduplication, then uploaded into Covidence systematic review software17 where a second deduplication took place. Final deduplication took place during screening. Screening and extraction were conducted by two authors (SD and ST). Details of included studies were extracted by one investigator using a standardized extraction tool (Supplemental 1) and reviewed for accuracy and completeness by a second investigator. Variables extracted included geographic region in which the study was done, data collection period, study design, intervention or exposure, comparison group, primary outcome, secondary outcome(s), hospital type (academic, community, other), HIE type (enterprise, state or regional, etc.), inclusion and exclusion criteria, number of study participants, any covariates, methods of statistical analysis (e.g., bivariate statistics and regressions), primary and secondary findings, whether findings favor the presence of HIE, and major study limitations (either reported or identified by the reviewers). Disagreement was resolved by consensus after discussion.

Risk of bias assessments were similarly conducted by one investigator and independently reviewed by a second investigator. The risk of bias assessment used the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute’s (NHLBI) Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies.18 Studies were deemed to be of “good,” “fair,” and “poor” quality based on investigator discussion structured by the NHLBI assessments.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

Because of the variation in HIE characteristics and outcomes examined, we determined that it was inappropriate to combine data quantitatively. We constructed evidence tables, organized data by the outcome, and critically analyzed studies to compare their findings and methods. We qualitatively synthesized the results of our included studies in a narrative format. Strength of evidence was assessed only for those outcomes examined by more than one study (otherwise, evidence of an effect was automatically considered “insufficient”). Strength of evidence assessments were conducted based on method guidelines from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), taking into account study limitations, directness, consistency, and precision of reported effects.19

Role of Funding Source

The funder had no role in the design, execution, or interpretation of this review.

RESULTS

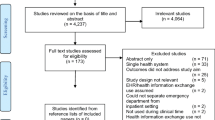

Of the 668 potentially relevant citations identified in our literature searches, 65 articles were selected for full-text review and 11 studies were ultimately deemed eligible for inclusion (see PRISMA diagram, Fig. 1). There were two studies that were excluded during extraction despite initially seeming to meet inclusion criteria. The first described trends in HIE usage and hospital readmission rates around an unrelated intervention, but did not compare the presence versus absence of HIE.20 The other study was excluded as the analysis included both inpatient and outpatient data that could not be separated.21 Another study had several analyses partially excluded for the same reason, but those inpatient analyses reported separately were included.22 Two studies were included that examined the effects of HIE based outside the inpatient setting (in the emergency department and a skilled nursing facility) because they both reported the effects of these HIEs on subsequent inpatient outcomes.23,24

Study characteristics are described in Table 1. The most common study design was a retrospective cohort; only 1 study was a randomized control trial. Most of the studies included patient data from one or more of the 10 US states (AR, CA, FL, IA, MA, MD, UT, VT, and WA). There were 2 studies from Israel and 1 from South Korea. Half of the studies examined multiple hospitals. Studies included a wide range of patient populations, ranging from patients newly admitted to inpatient units, (58%, 7 studies), to those recently discharged from inpatient units (17%, 2 studies) to patients following transfer to a different acute care hospital (25%, 3 studies). The majority of studies were not limited to specific diagnoses; however, one study only included patients admitted after myocardial infarction and another was limited to admissions related to six common conditions tracked by CMS (diabetes, asthma, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, chronic kidney disease, and hip fracture).

Of the 11 studies included, 3 were deemed of good quality (or low risk of bias), 6 were of fair quality, and 2 were deemed of poor quality. One poor-quality study was solely described in an abstract with insufficient detail to evaluate the methods. Another poor-quality study had an unclear methodology and therefore was deemed to be at high risk of bias.

Eight of the 11 studies reported healthcare utilization or cost outcomes, as described in Table 2. Five studies specifically examined readmission as an outcome—which we considered a distinct category of utilization as it is an important quality indicator used to evaluate hospitals.33 Four studies reported clinical outcomes including in-hospital mortality, discharge destination, and adverse drug events.

There were no clear trends between the outcomes reported and patient population or geographical region. There were slightly more net positive effects of HIEs reported by studies based on multi-hospital data versus single-hospital studies. There were two studies that verified actual usage of HIE at the time of admission—versus just noting the presence of HIE capabilities—and both reported significant reductions in unplanned readmissions when HIE was present and utilized.24,32 Neither study quantified how much HIE was utilized, however, but just reported it as a dichotomous variable if practitioners had opened the HIE software.

Readmission Rates

The reported effects on readmission rates were mixed but showed an association between HIE and reduced readmission rates in half of the 9 analyses conducted by 5 studies. One study found that fragmented readmissions (i.e., when a patient is readmitted to a different hospital) were also reduced when HIE was present.26 Two of the five studies that examined 30-day readmissions found a statistically significant reduction in rates when HIE was available compared to when it was not available. However, one of those studies only found a statistically significant reduction in readmissions when single-vendor HIE was present (i.e., multiple members of a health system exchanging information across a single vendor’s EHR platform) compared to no HIE (−0.8%, p=0.04), but not in the presence of enterprise HIE (i.e., the exchange of information across different EHR platforms by members of the same healthcare system) compared to no HIE (−0.4%, p=0.06).32 The other study that found a significant reduction in 30 day readmission rates at hospitals with HIE (−1.3%, p<0.01) also reported a statistically significant reduction in readmission rates at 45 days (−1.1%, p<0.05) and at 60 days (−0.9%, p<0.1).26 Another large analysis found the odds of readmission within 7 days to be significantly lower (−6.5%, p<0.001, OR 95%CI 0.90−0.97) when ED physicians accessed HIE prior to admission compared to when they did not.24 In contrast, a small study of patients discharged to skilled nursing facilities found no difference in readmission rates at 7, 14, or 30 days when HIE with the discharging hospital was enabled.23 There was also no significant difference found in 30-day readmission rates among Medicare patients discharged from hospitals with or without HIE.27

Clinical Outcomes

There were very heterogeneous clinical outcomes examined in 9 analyses across 5 studies. Two studies found lower odds of inpatient mortality and lower hazard ratio of 90-day mortality when HIE was present (OR=0.75, p<0.001, 95%CI 0.64–0.88; OR 0.68, p<0.001, 95%CI 0.49–0.78; and HR=0.78, p<0.001, 95%CI 0.57–0.86, respectively).30,31 In contrast, another study of myocardial infarction survivors found no significant difference in the odds of inpatient mortality when HIE was present.26 There was also no difference in the odds of an adverse drug event or in the likelihood of identifying a potentially harmful medication discrepancy when HIE was present according to a single randomized control trial.25 One study reported a statistically significant decrease in odds of “diagnostic discordance”—defined as the loss or acquisition of a diagnosis code following interhospital transfer—when HIE was available. However, this was a new outcome created by the authors that has not been widely studied in the hospital setting.31,34

Health Care Utilization and Cost

Of the 11 analyses from 8 studies reporting on health care utilization and cost outcomes, 6 found no difference in total charges,31 repeat imaging rates,29 or length of stay,22,27,28,31 when HIE was present compared to when HIE was not available. One study reported 3 analyses that found that when HIE was present there were statistically significantly greater total charges (+$4569, p<0.001), longer length of stay (+0.248 days, p<0.001), and increased number of procedures per admission (+0.241 procedures, p<0.001).26 In contrast, one study found a significant reduction (−9.5%, p<0.001, 95%CI 0.88–0.95) in odds of single-day admissions (considered by the authors to be markers of low quality), and another reported a significant reduction in length of stay after transfer (−3.0 days, p<0.01) when HIE was available compared to when it was not available.24,30

DISCUSSION

In this systematic review, we analyzed 11 studies evaluating the impact of HIE availability in the inpatient setting on patient and health system outcomes. Heterogeneous clinical outcomes across studies were difficult to compare; however, most studies found a decrease or no impact on patient mortality rates. Utilization and cost outcomes were less likely to show benefits from HIE. It was uncommon for studies to account for the actual use of HIE by providers rather than just HIE presence or absence.

Overall, the body of evidence around the effects of HIE on inpatient hospitalizations remains limited (Table 3). We would conclude that there is low strength of evidence that HIE is associated with a reduction in unplanned readmission rates. There is also low strength of evidence that HIE may reduce inpatient or 90-day post-discharge mortality rates. There is insufficient evidence to determine whether HIE is associated with length of stay or other measures of utilization or cost. We found no studies examining potential harm from HIEs.

Compared to prior systematic reviews of research on HIEs, we found several promising developments in the literature. First, there is more focus on clinical outcomes including patient mortality and morbidity. Second, though the vast majority of reviews remain observational, there has been a greater effort to statistically control for covariates affecting outcomes such as patient complexity or diagnosis-related group. Third, a few studies have even begun examining the actual use of HIE, rather than just the presence or absence of HIE at the hospital or system level. These studies still only consider HIE use as a dichotomous variable, however, and do not capture the amount of use, how it was used, or how the information obtained impacted clinical decision-making. Notably, these two studies that did consider actual use found that HIE use by providers was associated with modest reductions in odds/probability of readmission. Fourth, and finally, one study did compare the impacts of enterprise versus single-vendor HIEs—a comparison that warrants further investigation going forward as hospitals select information exchange strategies.

Since the last major review was published, the proportion of US hospitals performing all four domains of interoperability (e.g., send, receive, find, and integrate patient information) has more than doubled from 23% in 2014 to 55% in 2019.14 In 2019, three-quarters of hospitals reported electronically finding patient health information from sources outside their health system—53% of hospitals specifically used state, regional, or local HIE to do so.14 In early 2022, the Office of the National Coordinator released the long-awaited Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement providing governance for nationwide healthcare information exchange that was mandated with the passage of the 21st Century Cures Act in 2016.35 These efforts have been reflected in a similarly expanding body of research on HIE over the past 6 years. Our review provides a timely update on the state of the research on how HIE impacts patient and healthcare system outcomes.

Limitations

Our review has several limitations. First, the reported findings are limited to evaluations that appear in published literature. Second, most of the published studies we reviewed were exclusively observational with rare measurements of actual HIE use rather than just the presence or absence of HIE at the hospital or healthcare system level. Consequently, it is impossible to examine the strength of the effect of HIE if it is used more versus less, and so it is difficult to assess causality. Additionally, as previously mentioned, many studies relied on the same data sets such as the American Hospital Association Information Technology Supplemental Survey and the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Database. Finally, there were highly variable outcomes studied, so it is challenging to synthesize and come to conclusions about the evidence.

That the current state of the literature does not allow for a quantitative analysis of the impacts of HIE on the adult inpatient setting should be concerning to researchers in this field. If the goal is for sound evidence to inform policy decisions for health systems and governments to shape future HIE efforts, then future research efforts need to be selective in study design. In the future, to assess the impact of HIE, we would advocate for a more standardized selection of outcomes. It will improve the body of evidence around HIE as clinical and health care utilization outcomes are examined across multiple studies. The most common outcomes studied thus far that could be examined further include 30-day readmission rates, inpatient and post-discharge mortality, length of stay, and total charges or cost of admission. Additionally, given that HIE is now quite widespread—and in order to better establish associations between HIE and certain outcomes—we recommend that future studies try to incorporate more direct measures of HIE use by providers rather than just the presence or absence of HIE capabilities. Finally, there should be a greater examination of the effects of different types of health information sharing, such as the use of enterprise HIE versus single EHR vendor-driven data sharing to inform future policy and hospital strategizing.

CONCLUSION

There is low strength of evidence suggesting that HIE availability reduces unplanned readmission rates and possibly mortality. There is insufficient evidence for the impact of HIE on other clinical, cost, or utilization outcomes. To further our understanding of the impact of HIE, future studies need to select consistent outcomes, measure HIE use, and diversify the sources of hospital and exchange data.

References

The National Alliance for Health Information Technology Report to the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology on Defining Key Health Information Technology Terms. In: Department of Health and Human Services: Office of the National Coordinator; 2008. Available at: https://www.nachc.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Key-HIT-Terms-Definitions-Final_April_2008.pdf. Accessed 19 Apr 2022.

Kuperman GJ. Health-information exchange: why are we doing it, and what are we doing? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18(5):678-682.

Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act; Interoperability and Patient Access for Medicare Advantage Organization and Medicaid Managed Care Plans, State Medicaid Agencies, CHIP Agencies and CHIP Managed Care Entities, Issuers of Qualified Health Plans on the Federally-Facilitated Exchanges, and Health Care Providers. Federal Register. 2020(85):25510-25640.

Hahn J, Blom K. The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA; P.L. 114-10); No. R43962: Congressional Research Service; 2015.

Holmgren AJ, Adler-Milstein J. Health information exchange in US Hospitals: the current landscape and a path to improved information sharing. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(3):193-198.

Hincapie A, Warholak T. The impact of health information exchange on health outcomes. Appl Clin Inform. 2011;2(4):499-507.

Rudin RS, Motala A, Goldzweig CL, Shekelle PG. Usage and effect of health information exchange: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(11):803-811.

Hersh WR, Totten AM, Eden KB, et al. Outcomes from health information exchange: systematic review and future research needs. JMIR Med Inform. 2015;3(4):e39.

Menachemi N, Rahurkar S, Harle CA, Vest JR. The benefits of health information exchange: an updated systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2018;25(9):1259-1265.

Everson J, Butler E. Hospital adoption of multiple health information exchange approaches and information accessibility. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27(4):577-583.

Rahurkar S, Vest JR, Finnell JT, Dixon BE. Trends in user-initiated health information exchange in the inpatient, outpatient, and emergency settings. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021;28(3):622-627.

Henry J, Polypchuk H, Searcy T, Patel V. Adoption of Electronic Health Record Systems among U.S. Non-Federal Acute Care Hospitals: 2008-2015. In: Services DoHaH: Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology; 2016.

Apathy NC, Holmgren AJ, Werner RM. Growth in health information exchange with ACO market penetration. Am J Manag Care. 2022;28(1):e7-e13.

Pylypchuk Y, Johnson C, Patel V. State of Interoperability among U.S. Non-federal Acute Care Hospitals in 2018 State of Interoperability among U.S. Non-federal Acute Care Hospitals in 2018. In: Services DoHaH: Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology; 2020.

Adoption of Electronic Health Records by Hospital Service Type 2019-2021, Health IT Quick Stat #60. 2022; https://www.healthit.gov/data/quickstats/adoption-electronic-health-records-hospital-service-type-2019-2021. Accessed 4/19/22, 2022.

How health information exchanges impact adult inpatient outcomes: a systematic literature review. PROSPERO 2021. CRD42021274049. PROSPERO. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42021274049.

Covidence systematic review software [computer program]. Melbourne, Australia: Veritas Health Innovation.

National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Study Quality Assessment Tools. 2019; https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools. Accessed 19 Apr 2022.

Bekrman N, Lohr K, Ansari M, et al. Grading the Strength of a Body of Evidence When Assessing Health Care Interventions for the Effective Health Care Program of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: An Update. Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews [Internet]. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2013.

Schoenbaum AE, Seckman C. Impact of a prescription drug monitoring program on health information exchange utilization, prescribing behaviors, and care coordination in an emergency department. Comput Inform Nurs. 2019;37(12):647-654.

Jung HY, Vest JR, Unruh MA, Kern LM, Kaushal R, Investigators H. Use of health information exchange and repeat imaging costs. J Am Coll Radiol. 2015;12(12 Pt B):1364-1370.

Park H, Lee SI, Hwang H, et al. Can a health information exchange save healthcare costs? Evidence from a pilot program in South Korea. Int J Med Inform. 2015;84(9):658-666.

Cross DA, McCullough JS, Banaszak-Holl J, Adler-Milstein J. Health information exchange between hospital and skilled nursing facilities not associated with lower readmissions. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(6):1335-1345.

Ben-Assuli O, Shabtai I, Leshno M. Using electronic health record systems to optimize admission decisions: the Creatinine case study. Health Informatics J. 2015;21(1):73-88.

Boockvar KS, Ho W, Pruskowski J, et al. Effect of health information exchange on recognition of medication discrepancies is interrupted when data charges are introduced: results of a cluster-randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24(6):1095-1101.

Chen M, Guo S, Tan X. Does health information exchange improve patient outcomes? Empirical evidence from Florida Hospitals. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(2):197-204.

Daniel OU. Effects of health information technology and health information exchanges on readmissions and length of stay. Health Policy Technol. 2018;7(3):281-286.

Flaks-Manov N, Shadmi E, Hoshen M, Balicer RD. Health information exchange systems and length of stay in readmissions to a different hospital. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(6):401-406.

Rome BN, Schnipper JL, Maviglia SM, Mueller SK. Effect of shared electronic health records on duplicate imaging after hospital transfer. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(5):1617-1619.

Usher MG, Sahni N, Herrigel D, Olson A. Impact of electronic health records interoperability on inter-hospital transfer outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(2):S261-S262.

Usher M, Sahni N, Herrigel D, et al. Diagnostic discordance, health information exchange, and inter-hospital transfer outcomes: a population study. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(9):1447-1453.

Vest JR, Unruh MA, Freedman S, Simon K. Health systems' use of enterprise health information exchange vs single electronic health record vendor environments and unplanned readmissions. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2019;26(10):989-998.

Readmission Measures Overview. 2021; https://qualitynet.cms.gov/inpatient/measures/readmission. Accessed 26 Apr 2022.

Noje C, Costabile PM, Henderson E, et al. Diagnostic discordance in pediatric critical care transport: a single-center experience. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2021;37(12):e1616-e1622.

Notice of Publication of the Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement. Federal Register. 2022;87:2800-2876. Available at https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2022/01/19/2022-00948/notice-of-publication-of-thetrusted-exchange-framework-and-common-agreement. Accessed 19 Apr 2022.

Funding

Dr. Dupont’s work on this project and paper was supported in part by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under grant number D33HP31669 and title “Preventive Medicine Residencies” for $1,936,878. This information or content and conclusions are those of the author and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by HRSA, HHS, or the US Government.

Dr. Turbow is supported in part by the Program for Retaining, Elevating, and Supporting Early Career Researchers at Emory (PeRSEVERE) from the Emory School of Medicine, a gift from the Doris Duke Foundation, and through the Georgia CTSA NIH award (UL1-TR002378).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

ESM 1

(DOCX 23 kb)

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Dupont, S., Nemeth, J. & Turbow, S. Effects of Health Information Exchanges in the Adult Inpatient Setting: a Systematic Review. J GEN INTERN MED 38, 1046–1053 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07872-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07872-z