Abstract

Background

Health information exchange (HIE) notifications when patients experience cross-system acute care encounters offer an opportunity to provide timely transitions interventions to improve care across systems.

Objective

To compare HIE notification followed by a post-hospital care transitions intervention (CTI) with HIE notification alone.

Design

Cluster-randomized controlled trial with group assignment by primary care team.

Patients

Veterans 65 or older who received primary care at 2 VA facilities who consented to HIE and had a non-VA hospital admission or emergency department visit between 2016 and 2019.

Interventions

For all subjects, real-time HIE notification of the non-VA acute care encounter was sent to the VA primary care provider. Subjects assigned to HIE plus CTI received home visits and telephone calls from a VA social worker for 30 days after arrival home, focused on patient activation, medication and condition knowledge, patient-centered record-keeping, and follow-up.

Measures

Primary outcome: 90-day hospital admission or readmission. Secondary outcomes: emergency department visits, timely VA primary care team telephone and in-person follow-up, patients’ understanding of their condition(s) and medication(s) using the Care Transitions Measure, and high-risk medication discrepancies.

Key Results

A total of 347 non-VA acute care encounters were included and assigned: 159 to HIE plus CTI and 188 to HIE alone. Veterans were 76.9 years old on average, 98.5% male, 67.8% White, 17.1% Black, and 15.1% other (including Hispanic). There was no difference in 90-day hospital admission or readmission between the HIE-plus-CTI and HIE-alone groups (25.8% vs. 20.2%, respectively; risk diff 5.6%; 95% CI − 3.3 to 14.5%, p = .25). There was also no difference in secondary outcomes.

Conclusions

A care transitions intervention did not improve outcomes for veterans after a non-VA acute care encounter, as compared with HIE notification alone. Additional research is warranted to identify transitions services across systems that are implementable and could improve outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Risks to older patients after hospital discharge include medication problems, follow-up delays, and hospital readmission. Poor inter-site communication,1 flawed reconciliation of drug regimens,2 and uninformed provider decision-making3 contribute to care transition-related adverse events.3,4,5 Risk may be compounded when patients are admitted to a hospital outside of the system in which they receive routine care.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the largest integrated health system in the USA and delivers care across all settings. Nevertheless, among Veterans Affairs (VA)Medicare-eligible patients, a high percentage receive care both within and in systems outside VHA.6 Veterans with VA care may go to non-VA providers electively, or non-electively because of an acute condition that requires treatment at the nearest hospital.7 VA providers are often not aware of non-VA encounters until notified by non-VA providers, patients, or families.8 This is likely one reason dual VA and non-VA system use is associated with higher hospital admission and readmission rates and greater adverse events,9,10 in particular for older veterans.5,11,12

Health information exchange (HIE) allows health-care providers and patients to access and securely share medical information electronically.13 HIE organizations, often community-based and with public and private support, aggregate electronic health record data across multiple health-care providers and systems creating longitudinal views of a patient’s medical history.14 Although they use EHR systems, HIE organizations are distinct from EHR vendors, and typically develop access portals that require separate user credentialing.15 They also often provide notification services and direct-messaging capabilities. VHA has participated in HIE efforts,16,17,18 including query-based and direct-messaging forms of HIE.16,17,18,19 Notification of non-VA acute care encounters, enabled in some VA medical centers, provides an opportunity for VAs to implement care services after non-VA encounters such as care transitions interventions. These are interventions that target post-acute care risks and have been shown to improve outcomes after hospital discharge for older patients,20,21,22 but they depend on timely notifications of hospital admission and discharge. HIE notifications provide an opportunity to test such interventions across care systems and potentially ameliorate care fragmentation.23

The objective of this study was to use HIE to provide real-time VA notification of non-VA hospital admission or emergency department (ED) visit for older veterans, and compare HIE notification followed by a post-hospital care transitions intervention with HIE notification alone in a randomized trial. Hospital admission or readmission was the primary outcome; provider follow-up, patients’ understanding of their condition(s) and medication(s), and medication discrepancies were secondary outcomes. We hypothesized that veterans with non-VA acute care encounters who received a care transitions intervention enabled by HIE would have better post-discharge outcomes than those who received HIE notification alone.

METHODS

Subjects

This study was a cluster-randomized clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT 02689076) that took place from 2016 to 2019 and was completed before the onset of the COVID pandemic; the protocol has been described previously.24 The setting involved two urban, academic tertiary-care VA hospitals that were participants in their regional HIE networks. Veterans were eligible to participate if they 1) received primary care at one of the VA hospitals’ primary care clinics; 2) were 65 years or older; 3) consented to HIE between the VA and non-VA providers; and 4) had historical use of non-VA services (past 2 years) according to HIE records or self-report. Veterans receiving hospice care, residing in a long-term care facility, or receiving services that overlapped with the study’s care transitions intervention were excluded. Each site received approval from the local IRB, and patients provided written informed consent to participate in research.

HIE Notification

After enrollment, all veterans were followed prospectively for non-VA acute care encounters (hospital admissions or ED visits). If a non-VA acute care encounter occurred, the non-VA facility sent a real-time, electronic HL7 admission-discharge-transfer(ADT) message to the regional HIE network. By the next business day, VA study coordinators who subscribed to HIE network messages created a note within the VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) that identified the non-VA care facility where acute care was provided, the date, and the reason for the encounter. The note was routed electronically to the veteran’s VA primary care provider and became part of the veteran’s medical record. This notification process was implemented for study purposes and was not part of usual care.

Care Transitions Intervention

Prior to start of enrollment, primary care teams at the 2 study facilities were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 groups, blocked by VA facility. Patients with non-VA acute care encounters were assigned to one of the groups based on primary care team assignment; 1) receipt of a VA-based care transitions intervention (CTI) after HIE notification (HIE-plus-CTI group) or 2) HIE notification alone. For veterans in the HIE-plus-CTI group, after a veteran was discharged home from the index non-VA acute care encounter, a care transitions intervention was provided by a trained intervention social worker.

This intervention was adapted from a model developed by Coleman20,25 and focused on patient activation.26 It focused on increasing patients’ ability to manage their own care, as opposed to directly helping to fulfill patient needs. This meant that the social worker did not normally intervene on behalf of patients or communicate with providers, instead providing support for patients and caregivers to intervene on their own behalf—unless there was an urgent clinical need. The intervention targeted four “pillars:” 1) understanding and self-management of medications; 2) diagnosis-specific education and counseling, including “red flag” symptoms that require medical attention; 3) creation of a patient-centered record containing contact information, conditions, medications, and advance directives; and 4) self-management of appointments and of communication with providers. The CTI was delivered via one home visit 2–3 days after arrival home and three phone calls within 30 days. During the study, intervention social workers received in-person structured training by expert trainers and had regular intervention quality control checks.26 There were 2 modifications to the Coleman model: 1) patients were included after ED visit or hospitalization (whereas the original model was implemented only after hospitalization) and 2) there was no pre-hospital discharge patient visit because in most cases travel to the non-VA hospital was not feasible in a timely fashion.

Veterans in the HIE notification-alone group received usual care after discharge home from the index non-VA acute care encounter. This may have included a post-discharge phone call by a VA nurse within 72 h and scheduling of VA primary care follow-up appointments as needed.

Measures

The primary outcome measure was 90-day hospital admission or readmission after discharge home. If the patient was discharged to a rehabilitation facility after the index non-VA acute care encounter, the 90-day follow-up period began upon arrival home. We chose hospital admission as the primary outcome because this measure is important to patients, providers, and policymakers; it can be ascertained objectively and is commonly reported in studies of care transitions interventions20,21,22,27 and of HIE.28,29 We chose the 90-day period in part because the CTI requires 30 days to complete and has been shown to have a durable effect,20 and to optimize statistical power.

Secondary outcome measures were 1) 90-day ED visits, 2) VA primary care team phone contacts within 7 days of discharge home, 3) VA follow-up visit within 30 days of discharge home, 4) patients’ understanding of their condition(s) and medication(s), according to the Care Transitions Measure (CTM),30 as administered by phone 30 days after discharge home, and 5) high-risk medication discrepancies, defined as the number of discrepancies in anticoagulants, anti-diabetics, sedatives/hypnotics, psychiatric medications, and analgesics between patient self-report and medical record documentation.31,32,33

Baseline information included age, gender, race/ethnicity, insurance (Medicare, Medicaid), chronic conditions, comorbidity score,34 connection of conditions to military service, self-rated health,35 physical function using Activities of Daily Living (ADL)36 and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL)37 scales, cognitive function using the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire,38 site of enrollment, VA hospital use in the year prior to enrollment, travel time to the VA in minutes, identification of whether majority of care is VA (yes/no), and identification of a “regular” non-VA provider (yes/no). Baseline and outcome measures were collected by trained research assistants from electronic health records and patient interview. For HIE-plus-CTI group patients, the care transitions intervention was rated as complete if fewer than 25% of the intervention visits and calls were missing, partially complete if 25–50% were missing, and incomplete if greater than 50% were missing.

Analysis

Only veterans who had non-VA acute care encounters were included in analyses. Enrolled veterans could have more than one index non-VA acute care encounter included if encounters were at least 90 days apart. Targeted enrollment was 466 (233 participants per arm) based on 80% power to detect a 14% absolute difference in hospital readmission at 90 days (i.e., 26% in the HIE-plus-CTI group vs. 40% in the HIE-alone group), with a two-sided alpha of 0.05. Group baseline characteristics were assessed and compared using χ2 test or Fisher exact test for categorical variables and t test for continuous variables. Primary outcome analyses were conducted as intention to treat. Group comparisons were conducted while accounting for clustering within primary care teams and repeated observations of participants, using multilevel generalized linear mixed regression for binary outcomes, linear mixed regression to model CTM, and negative binomial regression to model number of high-risk medication discrepancies. In a sensitivity analysis, outcomes were compared using only one observation—the first non-VA acute care encounter—per participant. We also examined outcomes by level of completeness of the intervention, while adjusting for baseline differences between participants with complete and incomplete interventions. A significance level of p < 0.05 was adopted for all analyses. Analyses were performed using SAS statistical software (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

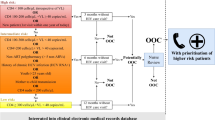

A total of 605 veterans were enrolled from 52 primary care teams (Fig. 1). Over the course of the study, 202 veterans (33.4%) experienced at least one index non-VA acute care encounter. Forty-one percent of index non-VA acute care encounters were hospital admissions and 59% were ED visits without hospital admission. The most common reasons for non-VA encounters were cardiovascular conditions, trauma, gastrointestinal diseases, infections, and neurological problems.39 If the acute care encounter was a hospital admission, the average hospital length of stay was 5.3 days (SD 5.5). Since 84 veterans experienced more than 1 eligible non-VA acute care encounter, a total of 347 index non-VA acute care encounters were included and assigned: 159 to HIE plus CTI and 188 to HIE alone, from 25 and 27 primary care teams, respectively (Fig. 1).

Veterans who had an index non-VA encounter were 76.9 years old on average, 98.5% male, 67.8% White, 17.1% Black, and 15.1% other (including Hispanic) race or ethnicity (Table 1). At baseline, 93.9% were cognitively intact and 81.2% had intact function in ADLs. Seventy-seven percent indicated that they receive most of their care at the VA, but 61.9% indicated that they have a regular non-VA provider. Baseline characteristics were balanced between study groups, except subjects in the HIE-plus-CTI group were less likely to report having Medicare coverage than subjects in the HIE-alone group (82.8% vs. 91.3%; p = .04) (Table 1).

Among veterans who had an index non-VA acute care encounter, 22.8% had a hospital admission or readmission within 90 days of discharge home (primary outcome). More of these follow-up encounters were non-VA than VA (Table 2). After accounting for clustering within primary care teams and repeated observations of participants, there was no difference in 90-day hospital admission or readmission between HIE-plus-CTI and HIE-alone groups (25.8% vs. 20.2%, respectively; risk diff 5.6%; 95% CI − 3.3 to 14.5%, p = .25) (Table 2). There were also no differences between HIE-plus-CTI and HIE-alone groups in 90-day ED visits or the composite of 90-day hospital admissions, readmissions, or ED visits (Table 2). In sensitivity analyses in which only the first index non-VA acute care encounter was included per participant, there were no differences between HIE-plus-CTI and HIE-alone groups.

Overall, 27.7% of veterans had phone contact with a VA primary care provider within 7 days of discharge home, and 33.4% had a VA primacy care in-person visit within 30 days. Including nurse (RN) contacts, 53.3% had a VA primacy care phone contact or in-person visit within 30 days. There were no differences between HIE-plus-CTI and HIE-alone groups in phone contacts at 7 or 30 days or in-person visits at 30 days (Table 3). Similarly, there were no differences between HIE-plus-CTI and HIE-alone groups in patients’ understanding of their condition(s) and medication(s) (CTM = 3.2 ± 0.6 in each group; p = .87) or in number of high-risk medication discrepancies (1.2 ± 1.3 and 1.1 ± 1.2 per person, in HIE-plus-CTI and HIE-alone groups, respectively; p = .77).

Overall, 75% of CTI interventions were rated as complete or partially complete and 25% were rated as incomplete. Patient activation improved over the course of the CTI, but only in those whose intervention was rated as complete, as reported previously.26 Among veterans assigned to HIE plus CTI, those with complete or partially complete interventions were less likely to experience hospital admission or readmission within 90 days after discharge home than those with incomplete interventions, but this did not remain statistically significant after adjusting for covariates (p = .17) (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

We hypothesized that HIE notification to VA primary care teams paired with delivery of an evidence-based, care transitions intervention would improve outcomes for veterans after a non-VA acute care encounter, as compared with HIE notification alone. However, we found no difference between study groups in 90-day hospital admission or readmission, ED use, primary care follow-up, patient post-discharge knowledge, or high-risk medication discrepancies. Findings from this study are consistent with prior studies of post-hospital care transitions interventions. Systematic reviews show that a variety of forms of care transitions interventions are associated with relative reductions of 9–23%21,40 in hospital readmission. However, a recent randomized study and rigorous non-randomized study found no benefit.41,42 In this trial, we employed a Coleman model,20 VA-based CTI without observed benefit.

There are several possible explanations for our findings. First, the study’s intervention focused on increasing patients’ activation to manage their own care, as opposed to directly helping to fulfill patient needs. This approach resulted in improved activation measures among CTI recipients, in particular those who received the complete intervention,26 but this improvement may not have translated into skills that patients and caregivers could specifically use to address issues of care fragmentation between VA and non-VA systems. In addition, our prior studies suggest that veterans who enroll in HIE16 and have non-VA events39 are older with greater comorbidity, which may require a more active, hands-on approach to CTI on the part of VA staff. The vast majority of 90-day readmissions in this study were non-VA readmissions. The CTI may have had lower potency to affect these readmissions since VA intervention social workers had less access to information on non-VA system follow-up appointments and prescribing, even with access to HIE.

Second, there were barriers to delivering the CTI that resulted in an incomplete intervention for 25% of recipients. Top barriers were difficulty reaching patients, patient refusal of home and telephone calls, and patients’ readmission to the hospital.26 Some veterans already had high levels of patient activation prior to the CTI; others indicated that they did not need CTI services, especially patients discharged from the ED who were potentially at lower risk than those discharged from the hospital. High baseline activation may reflect an increased effort by many hospitals, including the VA, to educate patients on self-management and follow-up care prior to hospital discharge.43,44 These findings are concordant with findings from other studies of care transitions services that report that intervention completion and other implementation issues may impact effectiveness.42 To maximize their impact among older adults, care transitions services need to connect with hard-to-reach patients, foster buy-in among patients who may be less engaged in the intervention, and accommodate physical, cognitive, and hearing and vision impairments.45 In addition, since older adults often rely on caregivers for assistance, including caregivers in supporting patient activation and self-management is crucial.46

Third, in this study, HIE alone involved primary care receipt of alerts of non-VA encounters, which may have improved outcomes in all participants and reduced the likelihood of detecting a benefit of CTI. In our prior work, we showed that HIE notification of acute care encounters improves primary care team follow-up as compared to a no-notification control group,47 and that primary care team members found the notifications helpful for filling information gaps and supporting timely follow-up.8 Others have shown a 2.9% reduction in 30-day readmissions associated with HIE electronic notifications.23 Though the comparison condition in this study, electronic notifications of outside encounters is not yet a standard of care. According to the U.S. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology, less than 40% of office-based primary care providers have the capability to receive electronic messages.48

Strengths of this study were the enrollment of a high-risk group that utilized care across VA and non-VA settings, and the implementation of timely HIE notifications enabling rapid post-discharge response to non-VA acute care events. A limitation of the study was the small sample size across only 2 sites. The study’s power was reduced from what was originally planned because of lower-than-expected overall 90-day hospitalization rates (expected: 33%; actual: 23%). However, there was no sign of an intervention effect on a composite of 90-day hospital admission, readmission, or ED visit, which occurred in 41.5% of cases and for which the study had adequate power. There was also no difference in any secondary outcome measure. A second limitation was that the CTI did not include a pre-hospital discharge visit since many of the acute care encounters were short, the CTI staff were VA based, and the acute care encounter was outside VHA. However, a pre-hospital discharge visit is not a core CTI element, and all core CTI elements were delivered, including a post-discharge home visit, a focus on patient activation, and the four pillars. Finally, timely follow-up by VA primary care teams was similarly low in both groups. This may have been because 1) it may have been more difficult to reach patients hospitalized outside the VA system (as opposed to within the VA system) because of incomplete information on time and place of discharge or inaccurate patient contact information, or 2) primary care team members may not have prioritized these follow-ups because notification of non-VA acute care encounters was not usual care.

In conclusion, a standardized, evidence-based care transitions intervention did not improve outcomes for veterans after a non-VA system acute care encounter, as compared with HIE notification alone. In 2020, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services mandated that hospitals send alerts to primary care providers when their established patients are seen for emergency or acute care.49 This rule may provide new opportunities for clinical practices to provide timely support to their patients after acute care encounters, as well as for clinical and health services researchers to test components of care transitions services. Additional research is warranted to identify transitions services that are implementable, that both address patient needs and improve activation, and that improve patient-centered outcomes.

References

Jones JS, Dwyer PR, White LJ, Firman R. Patient transfer from nursing home to emergency department: outcomes and policy implications. Acad Emerg Med. 1997;4(9):908-15.

Pronovost P, Weast B, Schwarz M, et al. Medication reconciliation: a practical tool to reduce the risk of medication errors. J Crit Care. 2003;18(4):201-5.

Leape LL, Bates DW, Cullen DJ, et al. Systems analysis of adverse drug events. ADE Prevention Study Group. JAMA.. 1995;274(1):35-43.

Nebeker JR, Hoffman JM, Weir CR, Bennett CL, Hurdle JF. High rates of adverse drug events in a highly computerized hospital. Arch Intern Med.. 2005;165(10):1111-6.

Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med.. 2003;138(3):161-7.

Research Findings From The VA-Medicare Data Merge Initiative. VA Information Resource Center (VIReC). 2003:http://www.virec.research.va.gov/DataSourcesName/VA-CMS/Medicare/USHreport.pdf.

Augustine MR, Mason T, Baim-Lance A, Boockvar K. Reasons Older Veterans Use the Veterans Health Administration and Non-VHA Care in an Urban Environment. J Am Board Fam Med. 2021;34(2):291-300.

Franzosa E, Traylor M, Judon KM, et al. Perceptions of event notification following discharge to improve geriatric care: qualitative interviews of care team members from a 2-site cluster randomized trial. J Am Med Inform Assoc.. 2021;28(8):1728-1735.

Helmer D, Sambamoorthi U, Shen Y, et al. Opting out of an integrated healthcare system: dual-system use is associated with poorer glycemic control in veterans with diabetes. Prim Care Diabetes. 2008;2(2):73-80.

Jia H, Zheng Y, Reker DM, et al. Multiple system utilization and mortality for veterans with stroke. Stroke. 2007;38(2):355-60.

Coleman EA, Smith JD, Raha D, Min SJ. Posthospital medication discrepancies: prevalence and contributing factors. Arch Intern Med.. 2005;165(16):1842-7.

Moore C, Wisnivesky J, Williams S, McGinn T. Medical errors related to discontinuity of care from an inpatient to an outpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(8):646-51.

What is HIE? Accessed September 13, 2021. https://www.healthit.gov/topic/health-it-and-health-information-exchange-basics/what-hie

Dixon BE. What is Health Information Exchange? . In: Dixon BE, ed. Health Information Exchange: Navigating and Managing a Network of Health Information Systems. Academic Press; 2016:3-20.

Adler-Milstein J, Garg A, Zhao W, Patel V. A Survey Of Health Information Exchange Organizations In Advance Of A Nationwide Connectivity Framework. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(5):736-744.

Dixon BE, Ofner S, Perkins SM, et al. Which veterans enroll in a VA health information exchange program? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24(1):96-105.

Byrne CM, Mercincavage LM, Bouhaddou O, et al. The Department of Veterans Affairs' (VA) implementation of the Virtual Lifetime Electronic Record (VLER): findings and lessons learned from Health Information Exchange at 12 sites. Multicenter Study. Int J Med Inform. 2014;83(8):537-47.

Dixon BE, Luckhurst C, Haggstrom DA. Leadership Perspectives on Implementing Health Information Exchange: Qualitative Study in a Tertiary Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Original Paper. JMIR medical informatics.. 2021;9(2):e19249.

Vest JR, Unruh MA, Shapiro JS, Casalino LP. The associations between query-based and directed health information exchange with potentially avoidable use of health-care services. Health Services Research. 2019;54(5):981-993.

Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min S-j. The Care Transitions Intervention: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch Intern Med.. 2006;166(17):1822-1828.

Le Berre M, Maimon G, Sourial N, Gueriton M, Vedel I. Impact of Transitional Care Services for Chronically Ill Older Patients: A Systematic Evidence Review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(7):1597-1608.

Naylor M, Brooten D, Jones R, Lavizzo-Mourey R, Mezey M, Pauly M Comprehensive discharge planning for the hospitalized elderly. A randomized clinical trial. Ann Intern Med.. 1994;120(12):999-1006.

Unruh MA, Jung HY, Kaushal R, Vest JR. Hospitalization event notifications and reductions in readmissions of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries in the Bronx, New York. J Am Med Inform Assoc.. 2017;24(e1):e150-e156.

Dixon BE, Schwartzkopf AL, Guerrero VM, et al. Regional data exchange to improve care for veterans after non-VA hospitalization: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2019;19(1):125.

Coleman EA. Falling through the cracks: challenges and opportunities for improving transitional care for persons with continuous complex care needs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):549-55.

Koufacos NS, May J, Judon KM, et al. Improving Patient Activation among Older Veterans: Results from a Social Worker-Led Care Transitions Intervention. J Gerontol Soc Work. May. 30 2021:1-15.

Naylor MD, Brooten D, Campbell R, et al. Comprehensive discharge planning and home follow-up of hospitalized elders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA.. 1999;281(7):613-20.

Hincapie A, Warholak T. The impact of health information exchange on health outcomes. Appl Clin Inform. 2011;2(4):499-507.

Vest JR, Kern LM, Campion TR, Jr., Silver MD, Kaushal R. Association between use of a health information exchange system and hospital admissions. Appl Clin Inform. 2014;5(1):219-31.

Coleman EA, Mahoney E, Parry C. Assessing the quality of preparation for posthospital care from the patient's perspective: the care transitions measure. Med Care. 2005;43(3):246-55.

Cooper JW. Adverse drug reaction-related hospitalizations of nursing facility patients: a 4-year study. South Med J. 1999;92(5):485-90.

Federico F. Preventing Harm from High-Alert Medications. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2007;33:537-542.

Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Harrold LR, et al. Incidence and preventability of adverse drug events among older persons in the ambulatory setting. JAMA.. 2003;289(9):1107-16.

Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol.. 2011;173(6):676-82.

Ware J, Jr., Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220-33.

Katz S, Ford A, Moskowitz R, Jackson B, Jaffe M. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychological function. J Am Med Assoc. 1963;185(12):914-9.

Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179-86.

Pfeiffer E. A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1975;23(10):433-41.

Kartje R, Dixon BE, Schwartzkopf AL, et al. Characteristics of Veterans With Non-VA Encounters Enrolled in a Trial of Standards-Based, Interoperable Event Notification and Care Coordination. J Am Board Fam Med. 2021;34(2):301-308.

Prvu Bettger J, Alexander KP, Dolor RJ, et al. Transitional care after hospitalization for acute stroke or myocardial infarction: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med.. 2012;157(6):407-16.

Huckfeldt PJ, Reyes B, Engstrom G, et al. Evaluation of a Multicomponent Care Transitions Program for High-Risk Hospitalized Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(12):2634-2642.

Van Spall HGC, Lee SF, Xie F, et al. Effect of Patient-Centered Transitional Care Services on Clinical Outcomes in Patients Hospitalized for Heart Failure: The PACT-HF Randomized Clinical Trial JAMA.. 2019;321(8):753-761.

Parrish MM, O'Malley K, Adams RI, Adams SR, Coleman EA. Implementation of the care transitions intervention: sustainability and lessons learned. Prof Case Manag. 2009;14(6):282-93.

Wee SL, Loke CK, Liang C, Ganesan G, Wong LM, Cheah J. Effectiveness of a national transitional care program in reducing acute care use. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(4):747-53.

Dossa A, Bokhour B, Hoenig H. Care transitions from the hospital to home for patients with mobility impairments: patient and family caregiver experiences. Rehabil Nurs. 2012;37(6):277-85.

Schulman-Green D, Jaser S, Martin F, et al. Processes of self-management in chronic illness. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2012;44(2):136-44.

Dixon B, Judon K, Schwartzkopf A, et al. Impact of event notification services on timely follow-up and rehospitalization among primary care patients at two Veterans Affairs medical centers. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021; 28(12):2593-2600.

Patel V, Pylypchuk Y, Parasrampuria S, Kachay L. Interoperability among Office-Based Physicians in 2015 and 2017. ONC Data Brief. 2019 2019;(47):12.

Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act; Interoperability and Patient Access for Medicare Advantage Organization and Medicaid Managed Care Plans, State Medicaid Agencies, CHIP Agencies and CHIP Managed Care Entities, Issuers of Qualified Health Plans on the FederallyFacilitated Exchanges, and Health Care Providers. Federal Register. May 1 2020;85(85)

Acknowledgements

Contributors: We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the following individuals to this project: Morgan Traylor, Brian Porter, Jessica Coffing, Jason Larson, Joanne Yi, Vanessa Duran, Tanieka Mason, and Andrew Bean.

Funding

This work was supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service (Grant no. IIR-10-146/ I01 HX001563). The article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the VHA or the US government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Prior Presentations: none

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Boockvar, K.S., Koufacos, N.S., May, J. et al. Effect of Health Information Exchange Plus a Care Transitions Intervention on Post-Hospital Outcomes Among VA Primary Care Patients: a Randomized Clinical Trial. J GEN INTERN MED 37, 4054–4061 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07397-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07397-5