Abstract

Background

A culture of improvement is an important feature of high-quality health care systems. However, health care teams often need support to translate quality improvement (QI) activities into practice. One method of support is consultation from a QI coach. The literature suggests that coaching interventions have a positive impact on clinical outcomes. However, the impact of coaching on specific process outcomes, like adoption of clinical care activities, is unknown. Identifying the process outcomes for which QI coaching is most effective could provide specific guidance on when to employ this strategy.

Methods

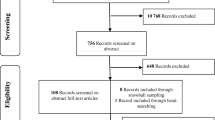

We searched multiple databases from inception through July 2021. Studies that addressed the effects of QI coaching on process of care outcomes were included. Two reviewers independently extracted study characteristics and assessed risk of bias. Certainty of evidence was assessed using GRADE.

Results

We identified 1983 articles, of which 23 cluster-randomized trials met eligibility criteria. All but two took place in a primary care setting. Overall, interventions typically targeted multiple simultaneous processes of care activities. We found that coaching probably has a beneficial effect on composite process of care outcomes (n = 9) and ordering of labs and vital signs (n = 6), and possibly has a beneficial effect on changes in organizational process of care (n = 5), appropriate documentation (n = 5), and delivery of appropriate counseling (n = 3). We did not perform meta-analyses because of conceptual heterogeneity around intervention design and outcomes; rather, we synthesized the data narratively. Due to imprecision, inconsistency, and high risk of bias of the included studies, we judged the certainty of these results as low or very low.

Conclusion

QI coaching interventions may affect certain processes of care activities such as ordering of labs and vital signs. Future research that advances the identification of when QI coaching is most beneficial for health care teams seeking to implement improvement processes in pursuit of high-quality care will support efficient use of QI resources.

Protocol Registration.

This study was registered and followed a published protocol (PROSPERO: CRD42020165069).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

High-quality health care is a priority for both patients and clinicians. In 2001, the Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine) outlined a strategy to improve the quality of health care in the USA anchored on six aims: safety, effectiveness, patient-centeredness, timeliness, efficiency, and equity [1]. The pursuit of these aims is the process of quality improvement (QI), which can be defined as “a framework we use to systematically improve the ways care is delivered to patients” [2]. QI is one aspect of the science of improvement, or “an applied science that emphasizes innovation, rapid-cycle testing … and spread in order to generate learning about what changes, in which context, produce results” [3]. Improvement science offers rigorous approaches to the attainment of high-quality care through clinic-level process refinement and the uptake of evidence-based practices [4, 5]. One approach to promote the pursuit of high-quality health care is the provision of longitudinal, expert support to help individuals and health care teams identify and implement areas of practice change [6,7,8]. QI coaching [9] is a commonly used strategy for the provision of longitudinal, expert support to clinical teams seeking to engage in QI processes.

A quality improvement (QI) coach supports an interdisciplinary health care delivery team in their pursuit of achieving sustained change and the improvement of clinical processes. Quality improvement coaches assist with goal setting and attainment, connect teams to system-level resources for change, and improve efficiency and team dynamics around improvement processes utilizing a variety of strategies [9]. The coach role can be agnostic to the clinical content area and does not require topical expertise. QI coaching is similar to other approaches that encourage the systematic adoption of high-quality, evidence-based practices such as facilitation. While there are multiple definitions, facilitation can generally be thought of as a “process of working with groups to support participatory ways of doing things.” [10] There are multiple scholarly fields that promote a coach-like role to support the optimal improvement of clinical care delivery (e.g., QI, implementation science, systems redesign), each with its own terms to describe the coaching-like processes (Supplementary Information) [11]. The effects of the coaching intervention can be measured at multiple levels including the level of care delivery such as provider behaviors or practice activities and policies (process outcomes) or at the level of patient care (clinical outcomes) [9].

To address the current gap in the literature, we investigated the effect of QI coaching on practice- or clinical team-level behaviors and process outcomes and found that QI coaching is a complex intervention that has the potential to improve the capacity for improvement activities at the team and practice level. Specifically, this review was conducted to support a type of QI coaching (i.e., transformational coaching) used in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) which has not been specifically described in the literature. Thus, we used a broad search strategy to identify interventions that shared the essential components that must be maintained to ensure fidelity to the VA’s QI coaching intervention. Components considered essential for the QI coach for this review include the following: (1) the coach is content-agnostic (not required to be an expert in the specific clinical topic or intervention that is the focus of the QI project). (2) The coach is external to the target of coaching (i.e., not a member of the health care delivery team being coached). (3) The coach aims to catalyze and/or build capacity for sustained change and improvement through activities such as assisting with goal setting, goal attainment, connection to system-level resources for change, and/or improving efficiency and team dynamics around change/improvement processes.

METHODS

Study Design

This work is part of a larger Veterans Health Administration (VHA)–funded report (www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp), which addresses the effects of QI coaching on practices, providers, patients, and processes. We established an a priori published protocol (PROSPERO: CRD42020165069) and followed PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidance [12].

Data Sources and Searches

In collaboration with a reference librarian, we searched MEDLINE® (via Ovid®), Embase (via Elsevier), and CINAHL Complete (via EBSCO) from inception (since the database began indexing journal content) through July 2021 (Supplementary Information). As there is no MeSH term existing for QI coaching and there are multiple terms for similar interventions, we identified the most commonly used terms and pseudonyms for a person (or persons) who potentially shared the essential components based on our operationalized definition of QI coaching listed above (e.g., practice facilitator, outreach visitor, QI coach). Specifically, we incorporated related terms from the fields of QI, improvement science, and implementation science, which themselves employ overlapping terms and methods pertaining to the support of clinical teams and practices in the uptake and improvement of evidence-based clinical processes. We also screened references from high-quality systematic reviews and studies identified by stakeholders during topic development.

Study Selection

Our inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Supplementary Information. Relevant terms identified after execution of the literature search were searched independently, and any references meeting our inclusion criteria were imported into two electronic databases (for referencing, EndNote®, Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA; for data abstraction, DistillerSR; Evidence Partners Inc., Manotick, ON, Canada). Citations classified for inclusion by at least one investigator at title and abstract were reviewed at full text by two investigators according to a priori established eligibility criteria. All articles meeting eligibility criteria at this level were included for data abstraction.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

One investigator abstracted data into a customized DistillerSR database; a second investigator reviewed data for accuracy. Data elements included descriptors to assess applicability, quality elements, intervention details, and all measured outcomes. Multiple reports from a single study were treated as a single data point, prioritizing results based on the most complete and appropriately analyzed data. Key features relevant to applicability included the match between the sample and target populations (e.g., age, large health care system). Two investigators independently assessed study quality using the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Risk of Bias (ROB) Tool [13]. We assigned summary ROB scores (low, unclear, or high) to individual studies (Supplementary Information).

Data Synthesis and Analysis

We collected all outcomes reported by studies meeting eligibility criteria and organized them by the level at which they produced potential changes. Specifically, we grouped outcomes by the level at which a process occurred: practice (e.g., processes requiring collaboration and simultaneous participation of multiple providers or clinical teams in a practice setting) or provider level (e.g., processes conducted by individual clinicians at the point of care such as ordering labs for a given condition). Other measures targeted clinical outcomes at the patient level (e.g., improved individual health outcomes). We described key study characteristics of the included studies using summary tables. Because complexity of targeted behavior change predicts intervention success, we grouped outcomes by the complexity of desired clinical practice or provider behavior promoted by the QI coach [14]. Specifically, those behaviors that required multiple steps or those requiring the agreement or collaboration of multiple individuals were considered more complex (e.g., adherence to multi-step guideline recommendations for asthma-related care) and those that could be completed individually less complex (e.g., ordering a lab). Then, we grouped outcomes by clinical care delivery similarity (e.g., ordering a lab, improving documentation). Within these groupings, we organized findings by study-level ROB.

Across included studies, we identified intervention activities employed by coaches to support interdisciplinary teams and matched them to the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) strategies [15]. ERIC was chosen because it is widely cited and incorporates relevant QI ideas. Given the conceptual heterogeneity in process of care outcomes assessed, the measure used to assess a given outcome, and the selection and dosing of coaching strategies employed, we described the specified outcomes narratively rather than calculating a summary effect.

We organized the adoption of targeted process of care activities according to the complexity of the specific behavior required by the relevant QI activity; specifically, we used the following eight categories: composite outcomes of multiple clinical processes of care, organizational processes of care, documentation, medication prescription, counseling, provider exams and procedures, lab tests, and vital signs. Heterogeneity, primarily of outcome measurement, precluded pooled assessment of the effect of coaching across these categories.

To support synthesis across the included studies, we employed a vote-counting method based on direction of effect [16, 17]. Following this approach, we categorized the intervention effect as harmful or beneficial based on the direction of effect without consideration for magnitude or statistical significance [16, 17]. We calculated the overall proportion of beneficial findings and obtained the exact 95% confidence interval (CI) for the true proportion of beneficial findings. We employed an exact binomial probability test to test the hypothesis that the intervention was truly ineffective, and provided the resulting p-value (i.e., the probability of observed or more extreme proportion if, in fact, the proportion of beneficial studies is truly 0.5). Exact CIs and p-value were calculated using “binom.test” function in the R statistical package. The certainty of evidence was assessed using Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) [18]. Certainty of evidence assessment conveys the level of confidence in effect estimates supporting a given conclusion [18].

Role of Funding Source

The US Department of Veterans Affairs was not involved in the design, conduct, or analysis interpretation.

RESULTS

From 1983 screened citations, we reviewed 116 full-text articles and identified 23 unique studies (all cluster-randomized trials [CRTs]) (Fig. 1) [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. All studies were conducted across North America, Europe, and Australia. All but two trials were conducted within the primary care setting and one study was conducted in the VA [25]. Among the included studies, two were in children and twenty-one were in adults. The targets of the coaching included diabetes (n = 3), mental health (n = 1), and preventive services (n = 15). Details of each of the 23 included studies are in Table 1.

Terms used for the QI coach–like role included practice facilitator, practice outreach facilitation, practice coach, nurse facilitator, nurse prevention facilitator, and outreach visitor. Interventions varied in duration from 4 to 48 months. Coaches employed varied combinations of 13 distinct implementation strategies. Studies reported a median of 5.56 implementation strategies (range 3 to 9) delivered by the coach-like role. The four most used coach-delivered implementation strategies were to develop a formal implementation plan (19/23 studies), audit and provide feedback (18/23), develop/distribute educational materials (17/23), and conduct educational outreach visits (17/23). The least used strategies were organizing clinician team meetings (3/23) and developing stakeholder interrelationships (2/23). Table 2 details the transformational coaching activities used in the included studies.

Across the included studies, four studies measured practice-level outcomes, nineteen measured provider-level outcomes, and eight measured patient-level outcomes (Supplementary Information). Nine studies evaluated composite measures of process of care activities (i.e., outcomes which included the conduct of multiple disease-specific or clinical care approach actions). Overall, interventions typically targeted multiple simultaneous processes of care activities requiring disparate clinical behaviors (e.g., ordering a lab test, complicated patient counseling), but which were usually linked by a common goal (e.g., improving management and outcomes for a specific disease).

Of the nine trials that assessed the composite process of care outcomes, six were low or unclear ROB and two were high ROB. Six of eight low or unclear ROB trials favored the intervention (75%; 95% CI 35 to 97%). The probability of observing 75% or more trials with a beneficial effect, assuming the proportion of beneficial studies is truly 0.5, is p = 0.29. For the organizational process of care outcomes, four of five trials (including the two low ROB studies) favored the coaching interventions (80%; 95% CI 28 to 99%; p = 0.38). Of the five studies (1 unclear and 4 high ROB) that assessed the effect of coaching on appropriate documentation, three included outcomes that favored the interventions (60%; 95% CI 15 to 95%; p = 1). Six of seven studies (2 unclear and 4 high ROB) testing the effect of coaching on appropriate medication prescriptions contributed to the analysis. Four of these six studies included at least one outcome that favored the coaching intervention (66%; 95% CI 22 to 96%; p > 0.69). The three trials (1 unclear and 2 low ROB) that assessed the effect of coaching on counseling provision favored the intervention (100%; 95% CI 29 to 100%). Four trials assessed the provision of appropriate exams or procedures, and three out of those four included at least one outcome that favored the interventions (75%; 95% CI 19 to 99%). Of the six trials that assessed the effect of coaching on ordering of labs or vitals, all but one included at least some outcomes that favored the intervention (83%; 95% CI 36 to 100%; p = 0.22). Figure 2 shows a high-level summary of these results.

Two trials measured the effect of coaching on QI process goal attainment. One unclear ROB study found a significant increase in the number of QI projects per practice in the intervention versus the comparator arms with a mean of 3.9 QI projects per practice versus 2.6 (p < 0.001). In a high ROB trial, there was no significant difference between the intervention and control practices in the percentage of mean QI indicators at or above target (p > 0.2). No studies directly addressed the self-efficacy of team members related to QI method skills or a specific QI project activity. No trials addressed the effect of QI coaching or similar roles on team member knowledge.

Certainty of Evidence

Overall, our assessment of the certainty of evidence based on GRADE ranged from very low to low across outcomes (see Table 3). Downgrading, or causes for lower certainty, included imprecision, inconsistency, and a high risk of bias.

DISCUSSION

QI coaching is a complex intervention that has the potential to promote high-quality care through effective and efficient implementation of improvement activities at the team and practice level. We identified 23 trials that addressed the effects of QI coaching primarily in the context of primary care practices. We found that coaching interventions seemed to have more of an impact on less complex tasks like documentation possibly due to fewer implementation barriers. Process tasks that were more complex like medication prescription have lower confidence ratings due to the imprecision of the outcome measurement. While our confidence in these findings was found to be low to very low due to imprecision, inconsistency, and high risk of bias, the results suggest that clinical teams may be able to preferentially identify types of QI activities most likely to benefit from coaching support and thus help to facilitate the efficient use of process improvement resources around the implementation of evidence-based guidelines within busy clinical practices.

Our findings are largely consistent with and build on recently conducted reviews of roles like QI coaching, specifically external change agents and practice facilitation. Baskerville and colleagues [42] conducted a systematic review of 23 articles looking at the impact of practice facilitation on evidence-based practice behavior. Their approach differed from ours in that they considered the adoption of evidence-based guidelines to be a conceptually common outcome measure and did not distinguish between high and low complexity guidelines. They calculated standardized mean differences across studies and combined them for a pooled estimate. With this approach, they reported an effect size of 0.56 (95% CI 0.43 to 0.68) favoring practice facilitation in the adoption of evidence-based guidelines. However, we considered the adoption of evidence-based processes of care by the complexity of the care activity and noted that there appears to be variation in the effect of coaching-type roles on different types of processes of care. Additionally, our review differed from Baskerville et al. [42] in that it included a more expansive definition of the coaching intervention and focused on process outcomes.

A more recent review by Wang and colleagues [43] examined the impact of an intervention similar to QI coaching (i.e., practice facilitation) on chronic disease management in primary care. They grouped outcomes by type of outcome (e.g., lab vs diagnosis) within disease group (e.g., cervical cancer process of care measures vs chronic kidney disease process of care). This approach is consistent with the way interventions are often designed, specifically around the management of a particular disease; however, it could mask differences in effect by the complexity of the process of care. Across 25 studies, Wang et al. [43] concluded that process measures improved 8.8% with screening, and diagnosis improved the most. In contrast, we found the best evidence for a likely effect on the composite process of care outcomes (which were usually disease-specific and more general like preventive guidelines), organizational processes of care, counseling, and simple tasks like ordering of labs and vital signs. We found an uncertain effect on documentation (including documentation of diagnoses) and likely no effect on the prescription of disease-appropriate medications.

While there has been increased awareness about what coach-like interventions consist of, as well as their effectiveness, [42] QI coaching utilization remains uneven. One reason for this variability could be the barrier of establishing and sustaining funding for these roles, especially from smaller, independent practices. However, the benefits of using a coach to implement improvement activities could outweigh this initial cost. Prior reviews have also looked at which aspects of coach-like roles are likely contributors to an overall effect. Alagoz and colleagues [44] explored the role of external change agents in promoting changes in health care organizations in small primary care clinics across 21 included studies. They concluded that clinic-level individualized follow-up via practice facilitation is the most effective approach; however, the most commonly employed approaches are academic detailing and audit and feedback. Similarly, we found that audit and feedback (89% studies) and academic detailing, or educational outreach visits (68% studies), were among the most commonly used implementation strategies along with developing a formal implementation plan (95%) and distributing educational materials (74%), and that only 10 of 19 studies employed ongoing consultation (53%).

Limitations of the identified literature included loss of significant data when an entire practice (or cluster) dropped out of a study; inadequate descriptions of both the team members and patients; a lack of statistical consideration of clustering; and a lack of clearly identified primary outcomes. In addition, there was notable heterogeneity across study intervention core components, outcome measures, and the practice setting in which these studies took place. These factors along with inconsistency and imprecision of results led to downgrading the certainty of evidence. The uncertainty of these results could be addressed by more high-quality studies of QI coaching interventions, as well as investigation of coaching on very specific and consistently identified outcomes. Limitations of our approach to this review include potentially introducing heterogeneity by including literature from multiple fields of study and the loss of relevant information due to exclusion of studies with co-interventions, which prevented isolation of the coaching effect.

We also identified multiple gaps in the literature. First, few coaching interventions employed the strategies we identified as being most helpful in combination (e.g., stakeholder/leadership engagement and technical support). Second, most coaching interventions focused on predetermined QI projects rather than on the capacity for QI more generally. Third, all but one of the included interventions were conducted in primary care settings, so the effect of coaching in other clinical settings (e.g., inpatient, subspecialty clinics) is unknown.

CONCLUSION

QI coaching is a complex intervention that has the potential to improve the capacity for improvement activities at the team and practice level. QI coaching, and other interventions with similar characteristics (i.e., facilitation, outreach visitors), may have an effect on certain processes of care activities including composite process of care outcomes, ordering of labs and vital signs, and possibly on changes in the organizational process of care and delivery of appropriate counseling. Differences among studies in the description and dosing of implementation strategies employed by coaches, as well as outcome measurement, precluded a more definitive estimate of effects. Future research that standardizes and provides more detail about when coaching interventions are most effective will better support future comparisons and implementation efforts.

References

Institute of Medicine. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. 2001. https://doi.org/10.17226/10027

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Practice Faciliation Handbook. Training Modules for New Facilitators and Their Trainers. Available at: https://www.ahrq.gov/ncepcr/tools/pf-handbook/index.html. Accessed May 12, 2020.

Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Science of Improvement. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/about/Pages/ScienceofImprovement.aspx. Accessed July 14, 2020.

Improvement Science Research Network. What is Improvement Science? Available at: https://isrn.net/about/improvement_science.asp. Accessed July 14, 2020.

Shojania KG, Grimshaw JM. Evidence-based quality improvement: the state of the science. Health Aff. (Millwood). 2005;24(1):138-50. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.24.1.138

Berta W, Cranley L, Dearing JW, Dogherty EJ, Squires JE, Estabrooks CA. Why (we think) facilitation works: insights from organizational learning theory. Implement Sci. 2015;10:141. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0323-0

Liddy C, Laferriere D, Baskerville B, Dahrouge S, Knox L, Hogg W. An overview of practice facilitation programs in Canada: current perspectives and future directions. Healthcare policy = Politiques de sante. 2013;8(3):58-67.

Kitson A, Harvey G, McCormack B. Enabling the implementation of evidence based practice: a conceptual framework. Qual Health Care. 1998;7(3):149-58. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.7.3.149

World Health Organization. Regional Office for South-East Asia. Coaching for quality improvement: coaching guide. New Delhi: World Health Organization. Regional Office for South-East Asia; 2018.

Department of Veterans Affairs. Using Implementation Facilitation to Improve Care in the Veterans Health Administration. Available at: https://www.queri.research.va.gov/tools/implementation.cfm. Accessed July 14, 2020.

Ballengee LA, Rushton S, Lewinski AA, Hwang S, Zullig LL, Ball Ricks KA, et al. Transformational Coaching: Effect on Process of Care Outcomes and Determinants of Uptake. VA ESP Project 09–010. 2020. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/management_briefs/default.cfm?ManagementBriefsMenu=eBrief-no178.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097-e. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). Suggested risk of bias criteria for EPOC reviews. EPOC Resources for review authors, 2017. Available at: http://epoc.cochrane.org/resources/epoc-resources-review-authors Accessed May 12, 2020.

Pfadenhauer LM, Gerhardus A, Mozygemba K, Lysdahl KB, Booth A, Hofmann B, et al. Making sense of complexity in context and implementation: the Context and Implementation of Complex Interventions (CICI) framework. Implementation Science. 2017;12(1):21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0552-5

Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, Damschroder LJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10:21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1

Cochrane Training. Chaper 12: Synthesizing and presenting findings using other methods. Available at: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-12#_Ref524788589. Accessed May 29, 2020.

Cooper HM. Research synthesis and meta-analysis : a step-by-step approach. Los Angeles: Sage; 2010.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, et al. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2017;87:4-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006

Dickinson WP, Dickinson LM, Jortberg BT, Hessler DM, Fernald DH, Cuffney M, et al. A Cluster Randomized Trial Comparing Strategies for Translating Self-Management Support into Primary Care Practices. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2019;32(3):341-52.

Carroll JK, Pulver G, Dickinson LM, Pace WD, Vassalotti JA, Kimminau KS, et al. Effect of 2 Clinical Decision Support Strategies on Chronic Kidney Disease Outcomes in Primary Care: A Cluster Randomized Trial. JAMA Network Open. 2018;1(6):e183377.

Mold JW, Fox C, Wisniewski A, Lipman PD, Krauss MR, Harris DR, et al. Implementing asthma guidelines using practice facilitation and local learning collaboratives: a randomized controlled trial. Ann. Fam. Med. 2014;12(3):233-40.

Meropol SB, Schiltz NK, Sattar A, Stange KC, Nevar AH, Davey C, et al. Practice-tailored facilitation to improve pediatric preventive care delivery: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6):e1664-75.

Dickinson WP, Dickinson LM, Nutting PA, Emsermann CB, Tutt B, Crabtree BF, et al. Practice facilitation to improve diabetes care in primary care: a report from the EPIC randomized clinical trial. Ann. Fam. Med. 2014;12(1):8-16.

Parchman ML, Noel PH, Culler SD, Lanham HJ, Leykum LK, Romero RL, et al. A randomized trial of practice facilitation to improve the delivery of chronic illness care in primary care: initial and sustained effects. Implementation Science. 2013;8:93.

Chinman M, McCarthy S, Hannah G, Byrne TH, Smelson DA. Using Getting To Outcomes to facilitate the use of an evidence-based practice in VA homeless programs: a cluster-randomized trial of an implementation support strategy. Implementation Science. 2017;12(1):34.

Goodwin MA, Zyzanski SJ, Zronek S, Ruhe M, Weyer SM, Konrad N, et al. A clinical trial of tailored office systems for preventive service delivery. The Study to Enhance Prevention by Understanding Practice (STEP-UP). Am. J. Prev. Med. 2001;21(1):20-8.

Rask K, Kohler SA, Wells KJ, Williams JA, Diamond CC. Performance improvement interventions to improve delivery of screening services in diabetes care. J. Clin. Outcomes Manag. 2001;8(11):23-9.

Margolis PA, Lannon CM, Stuart JM, Fried BJ, Keyes-Elstein L, Moore DE, Jr. Practice based education to improve delivery systems for prevention in primary care: randomised trial. BMJ. 2004;328(7436):388. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38009.706319.47

Ornstein S, Jenkins RG, Nietert PJ, Feifer C, Roylance LF, Nemeth L, et al. A multimethod quality improvement intervention to improve preventive cardiovascular care: a cluster randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2004;141(7):523-32. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-141-7-200410050-00008

van Bruggen R, Gorter KJ, Stolk RP, Verhoeven RP, Rutten GE. Implementation of locally adapted guidelines on type 2 diabetes. Fam. Pract. 2008;25(6):430-7.

Due TD, Thorsen T, Kousgaard MB, Siersma VD, Waldorff FB. The effectiveness of a semi-tailored facilitator-based intervention to optimise chronic care management in general practice: a stepped-wedge randomised controlled trial. BMC Fam. Pract. 2014;15:65. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-15-65

Engels Y, van den Hombergh P, Mokkink H, van den Hoogen H, van den Bosch W, Grol R. The effects of a team-based continuous quality improvement intervention on the management of primary care: a randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2006;56(531):781-7.

Lobo CM, Frijling BD, Hulscher ME, Bernsen RM, Braspenning JC, Grol RP, et al. Improving quality of organizing cardiovascular preventive care in general practice by outreach visitors: a randomized controlled trial Prev. Med. 2002;35(5):422-9. https://doi.org/10.1006/pmed.2002.1095

Liddy C, Hogg W, Singh J, Taljaard M, Russell G, Deri Armstrong C, et al. A real-world stepped wedge cluster randomized trial of practice facilitation to improve cardiovascular care. Implementation Science. 2015;10:150.

Hogg W, Lemelin J, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Martin C, Moore L, et al. Improving prevention in primary care: evaluating the effectiveness of outreach facilitation. Fam. Pract. 2008;25(1):40-8.

Lemelin J, Hogg W, Baskerville N. Evidence to action: a tailored multifaceted approach to changing family physician practice patterns and improving preventive care. CMAJ. 2001;164(6):757-63.

Harris MF, Parker SM, Litt J, van Driel M, Russell G, Mazza D, et al. Implementing guidelines to routinely prevent chronic vascular disease in primary care: the Preventive Evidence into Practice cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e009397.

Gold R, Bunce A, Cowburn S, Davis JV, Nelson JC, Nelson CA, et al. Does increased implementation support improve community clinics' guideline-concordant care? Results of a mixed methods, pragmatic comparative effectiveness trial. Implementation Science. 2019;14(1):100.

Ruud T, Drake RE, Saltyte Benth J, Drivenes K, Hartveit M, Heiervang K, et al. The Effect of Intensive Implementation Support on Fidelity for Four Evidence-Based Psychosis Treatments: A Cluster Randomized Trial. Administration & Policy in Mental Health. 2021;19:19.

Shelley DR, Gepts T, Siman N, Nguyen AM, Cleland C, Cuthel AM, et al. Cardiovascular Disease Guideline Adherence: An RCT Using Practice Facilitation. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2020;58(5):683-90.

Zgierska AE, Robinson JM, Lennon RP, Smith PD, Nisbet K, Ales MW, et al. Increasing system-wide implementation of opioid prescribing guidelines in primary care: findings from a non-randomized stepped-wedge quality improvement project. BMC Fam. Pract. 2020;21(1):245.

Baskerville NB, Liddy C, Hogg W. Systematic review and meta-analysis of practice facilitation within primary care settings. Ann. Fam. Med. 2012;10(1):63-74.

Wang A, Pollack T, Kadziel LA, Ross SM, McHugh M, Jordan N, et al. Impact of Practice Facilitation in Primary Care on Chronic Disease Care Processes and Outcomes: a Systematic Review. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2018;33(11):1968-77.

Alagoz E, Chih MY, Hitchcock M, Brown R, Quanbeck A. The use of external change agents to promote quality improvement and organizational change in healthcare organizations: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018;18(1):42.

Stange KC, Goodwin MA, Zyzanski SJ, Dietrich AJ. Sustainability of a practice-individualized preventive service delivery intervention. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2003;25(4):296-300. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00219-8

Deri Armstrong C, Taljaard M, Hogg W, Mark AE, Liddy C. Practice facilitation for improving cardiovascular care: secondary evaluation of a stepped wedge cluster randomized controlled trial using population-based administrative data. Trials [Electronic Resource]. 2016;17(1):434.

Noel PH, Romero RL, Robertson M, Parchman ML. Key activities used by community based primary care practices to improve the quality of diabetes care in response to practice facilitation. Qual. Prim. Care. 2014;22(4):211-9.

Perry CK, Damschroder LJ, Hemler JR, Woodson TT, Ono SS, Cohen DJ. Specifying and comparing implementation strategies across seven large implementation interventions: a practical application of theory. Implementation Science. 2019;14(1):32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0876-4

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge our operational partners, Kathleen Glow-Morgan and Christine Rovinski, for their transformational coaching expertise; and Liz Wing for editorial assistance. Additionally, we would like to thank the following key stakeholders and technical expert panel members for their feedback during the development and execution of this project: Carol Callaway-Lane, Kay Calloway, Laura Damschroder, Michael Davies, Michael G. Goldstein, and David Goodrich.

Funding

This project was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (ESP 09–010). This work was also supported by the Durham Center of Innovation to Accelerate Discovery and Practice Transformation (ADAPT) (CIN 13–410) at the Durham VA Health Care System. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official views or policy of the Department of Defense or its Components. Dr. Ballengee’s effort was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Quality Scholars Program. Dr. Goldstein’s effort is supported by VA HSR&D CDA award #13–263. Dr. Lewinski’s effort is supported by a VA HSR&D grant #18–234. Dr. Ramos’s effort is supported by the National Cancer Institute (R01CA2011790), and the National Institute on Aging (P30 NIA 12734132; U24-AG058556-03); Dr. Rushton receives funding from HRSA Primary Care Training and Enhancement Program (TOBHP29992), which is not related to this work. Dr. Brahmajothi’s effort is supported by DoD grant (W81XWH1810454).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Lewinski reports receiving funding from Otsuka and the PhRMA Foundation. Dr. Zullig reports receiving research funding from Proteus Digital Health and the PhRMA Foundation as well as consulting with Novartis, none related to the current work.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ballengee, L.A., Rushton, S., Lewinski, A.A. et al. Effectiveness of Quality Improvement Coaching on Process Outcomes in Health Care Settings: A Systematic Review. J GEN INTERN MED 37, 885–899 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07217-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07217-2