Abstract

Background

Treatment by high-opioid prescribing physicians in the emergency department (ED) is associated with higher rates of long-term opioid use among Medicare beneficiaries. However, it is unclear if this result is true in other high-risk populations such as Veterans.

Objective

To estimate the effect of exposure to high-opioid prescribing physicians on long-term opioid use for opioid-naïve Veterans.

Design

Observational study using Veterans Health Administration (VA) encounter and prescription data.

Setting and Participants

Veterans with an index ED visit at any VA facility in 2012 and without opioid prescriptions in the prior 6 months in the VA system (“opioid naïve”).

Measurements

We assigned patients to emergency physicians and categorized physicians into within-hospital quartiles based on their opioid prescribing rates. Our primary outcome was long-term opioid use, defined as 6 months of days supplied in the 12 months subsequent to the ED visit. We compared rates of long-term opioid use among patients treated by high versus low quartile prescribers, adjusting for patient demographic, clinical characteristics, and ED diagnoses.

Results

We identified 57,738 and 86,393 opioid-naïve Veterans managed by 362 and 440 low and high quartile prescribers, respectively. Patient characteristics were similar across groups. ED opioid prescribing rates varied more than threefold between the low and high quartile prescribers within hospitals (6.4% vs. 20.8%, p < 0.001). The frequency of long-term opioid use was higher among Veterans treated by high versus low quartile prescribers, though above the threshold for statistical significance (1.39% vs. 1.26%; adjusted OR 1.11, 95% CI 0.997–1.24, p = 0.056). In subgroup analyses, there were significant associations for patients with back pain (adjusted OR 1.25, 95% CI 1.01–1.55, p = 0.04) and for those with a history of depression (adjusted OR 1.28, 95% CI 1.08–1.51, p = 0.004).

Conclusions

ED physician opioid prescribing varied by over 300% within facility, with a statistically non-significant increased rate of long-term use among opioid-naïve Veterans exposed to the highest intensity prescribers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Opioid use continues to fuel one of the most pressing public health crises in the USA, with over 47,000 opioid-related overdose deaths in 2017 alone.1 There is significant concern that physician prescribing is an important driver of this epidemic.2, 3 In national surveys, nearly 80% of heroin users endorsed non-medical use of prescription opioids as their first exposure to opioid misuse.4, 5 Therefore, great attention has been placed on the risks of opioid prescribing,6 particularly the likelihood of patients transitioning to long-term opioid use and dependence. In particular, the millions of Veterans treated in Veterans Health Administration (VA) facilities represent a vulnerable population in the opioid epidemic. The prevalence of chronic pain in some Veteran populations ranges from 50 to 60%,7 and those with mental illness have high rates of high-risk opioid use (e.g., concurrent use with benzodiazepines).8 Furthermore, the risk of opioid overdose in Veterans is twice as high as in the US population.9

Recent research has demonstrated a broad array of potential risks associated with even short-term opioid prescribing that could be contributing to the epidemic of opioid-related mortality. Observational studies conducted among national cohorts of commercially insured individuals have shown that increasing duration of opioid prescribing is associated with higher rates of chronic opioid use and overdoses.10, 11 Among the Medicare population, a quasi-experimental study of opioid-naïve patients found that a higher likelihood of receiving a short opioid prescription in the emergency department (ED) was associated with significantly higher rates of subsequent long-term opioid use.12 However, the extent to which these findings generalize to populations outside of Medicare is not clear.

To address this question, we examined the extent to which variation in individual ED physicians’ opioid prescribing was independently associated with long-term opioid use in Veterans. We thus aimed to replicate within the VA the prior work conducted in a Medicare population12 to determine whether Veterans treated by VA ED physicians with high opioid prescribing rates may be at higher risk of transitioning to chronic opioid use. Beyond examining a new population, this study addresses limitations in the prior analysis in Medicare,12 which was not able to directly attribute opioid prescriptions to individual ED physicians and had limited sample sizes of patients within physicians and within hospitals.

METHODS

Data Sources and Study Population

We linked national patient-level data for calendar years (CY) 2012–2013 from the VA Corporate Date Warehouse, including patient demographics and diagnosis codes for all inpatient and outpatient visits; medication data on dispensed outpatient prescriptions, including the provider writing the prescription and the site of care; and pain scores for ED encounters. We used data from 2012 to 2013 to best match the study period examined by Barnett et al. with the data available.12

We identified all patients with an index ED visit at the VA in 2012 (study cohort flow shown in Figure 1). To do so, we first identified all ED providers, defined as providers who treated at least 30 patients in an ED setting and who had > 90% of their prescriptions associated with an ED visit (n = 2468 providers). We used VA clinic “stop codes” corresponding to the emergency department (130 and 131, urgent care) to identify sites of care for emergency visits, which we subsequently define as ED care.13, 14 We then identified all patients with their first (index) ED visit in 2012 whose sole emergency provider was one of these ED providers (n = 825,888 visits), and assigned each index ED visit to that provider.

To focus the analysis on individuals receiving care from the VA system, we restricted the analytic sample to patients who were continuously enrolled in VA and had at least one face-to-face visit in the 12 months before the index ED visit (n = 649,375; Fig. 1). We also limited the sample to “opioid-naïve” patients, defined as no fills of prescription opioid within 6 months visible in the VA system prior to the index ED visit (n = 416,053, subsequently referred to as “opioid naïve”). In addition, we excluded index ED visits resulting in hospitalization for which prescriptions could not be attributed to an ED provider (n = 77,023), or where long-term opioid use was likely clinically appropriate (patients with hospice claims, n = 8077, or a cancer diagnosis, n = 28,218, within 1 year prior or after index ED visit). Finally, to ensure adequate sample size at provider and facility levels, we excluded patients seeing providers with fewer than 30 ED patients during the study period or from facilities with fewer than five ED providers (n = 9761).

This study was approved by the institutional review board at the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System.

Defining ED Provider Opioid Prescribing Intensity

To address the selection bias inherent in the characteristics of patients receiving opioids versus those who do not, we defined our exposure for patients based on the opioid prescribing intensity of the ED provider treating them. Adapting the technique used by Barnett et al.,12 we defined the main exposure in this analysis as whether the patient was treated by a “high-intensity” or “low-intensity” opioid prescribing provider at the index ED visit. Because patients are largely unable to choose their ED provider, this exposure is plausibly independent from patient characteristics. We examine the validity of this assumption with multiple tests described below.

For each index encounter, we captured opioid prescriptions using VA drug product names written by ED providers on the same day or day after the index visit. After identifying all opioid prescriptions associated with index ED visits and the corresponding ED providers, the opioid prescribing rate (OPR) for each provider was calculated as the proportion of each providers’ ED visits with an opioid prescription filled.

We grouped providers into quartiles based on their OPR within their facility. The providers in the highest and lowest quartiles in a facility were assigned to the high-intensity and low-intensity groups, respectively.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was long-term opioid use, defined as > 180 days of opioids supplied in the 12 months after an index ED visit, excluding prescriptions within 30 days after the index visit since the likelihood of getting an opioid in that period is directly related to the OPR of the provider seen.12 Secondary outcomes included the proportion of patients in the subsequent 12 months from an index ED visit with any day of a dose > 100 oral morphine milligram equivalents (MME) (“high opioid dose”). For opioid prescriptions filled between days 31 and 365 after the index ED visit, we calculated the daily MME using standard conversion factors from the Centers for Disease Control.15 We excluded opioids with unclear or variable MME conversion factors for this analysis, such as liquid formulations. We also examined rates of hospital encounters (ED visits and/or hospitalizations), including those potentially related to adverse effects of opioids during this same time period after an index ED visit.12, 16

Patient Covariates

We constructed baseline variables for age, sex, race/ethnicity, census region, and comorbidities. We obtained the census region based on facility location. Comorbidities within 1 year prior to the index ED visit were defined as the number of Charlson comorbidity conditions17 and other disease states that could influence opioid use, including history of substance use disorder, depression, anxiety, serious mental illness, and prior pain diagnoses (subdivided into back/joint, chest, or other musculoskeletal diagnoses).18, 19 Serious mental illness was defined by the presence of an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9), code for schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder, bipolar, delusion and paranoid disorders, and other non-organic psychoses. To assess case mix at the index ED visit, we also categorized the primary diagnosis at the index ED visit according to Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) groups.20 Because E codes (those that define injury) can serve as the primary diagnosis within VA (unlike in Medicare), we adapted the CCS algorithm to recategorize these codes, when able, into other CCS groups. We also extracted the initial patient-reported pain score (rated from 0 to 10, 10 being the worst) within 12 h of each index ED visit, with most (75.7%) reported within 0 or 1 h of the index ED visit. Pain scores were missing for 11.4% of ED visits, which were not included in the pain score analysis.

Statistical Analysis

We addressed the issue of selection bias through the premise that opioid-naïve patients are unlikely to choose their ED physician once they have chosen a facility. To assess this assumption, we first compared patient characteristics among patients treated by high- versus low-intensity prescribers, using chi-squared tests for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables. We also compared the distribution of categories of CCS conditions and plotted the rates of the 10 most frequent groups of primary diagnoses for ED visits by CCS groups to assess balance in the case mix at the index ED visit. We also examined ED physicians’ opioid prescribing patterns by patients’ presenting pain score, stratified by the four quartile groups of provider opioid prescribing intensity.

We computed unadjusted rates and odds ratios for each outcome according to whether a patient was treated by a high- or low-intensity prescriber. To estimate adjusted odds ratios for each outcome, we fit two separate sets of multivariable logistic regression models. We first adjusted for all available patient covariates (age, sex, race/ethnicity, history of substance use disorder, depression, anxiety, serious mental illness, pain diagnoses, number of Charlson chronic conditions) and region. In the second set of models, we included fixed effects for CCS condition groups to additionally adjust for primary diagnosis at each index ED visit. We also ran several pre-specified subgroup analyses stratifying patients by specific primary diagnoses at the index ED visit (e.g., back pain or injury) or comorbidities (e.g., depression, serious mental illness) to assess for heterogeneity. We also examined the extent to which unadjusted and adjusted estimates differed, which reflects the influence of differences in observable patient characteristics on the outcomes.

For all models, we used robust standard errors clustered at the facility level to account for grouping of patients within facility.21 To account for missing data in key covariates (race for 2.5% and gender in 0.001% of observations), we used multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE) across 10 multiply imputed datasets.22 Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and STATA 14 (College Station, TX).

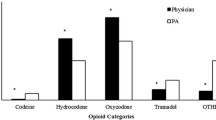

RESULTS

Our study sample consisted of 304,601 opioid-naïve Veterans with an index ED visit in 2012 treated by 1607 ED physicians in 105 facilities (Fig. 1). Among these Veterans, 57,738 (19.0%) were treated by physicians classified as low-intensity prescribers and 86,393 (28.4%) were treated by high-intensity physician prescribers. Although the characteristics of patients treated by low- versus high-intensity prescribers had clinically small differences, due to large sample size, differences for race, comorbid illness, history of substance use disorder, and region were statistically significant (Table 1). There were also small differences by prescriber intensity for the primary diagnosis during the ED visit, with no apparent pattern favoring particular diagnoses (Table 1 and online Appendix Figure 1). Across high- and low-intensity prescribers, the total morphine milligram equivalents (median [IQR] 120 [75, 180] for low and 135 [90, 200] for high p ≤ 0.001 by Wilcoxon two-sample test) differed slightly. Days supplied with opioid prescriptions were similar (median [IQR] 7 [5–10] for low and 7 [5–10] for high, p = 0.92).

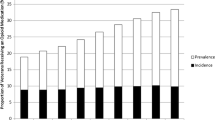

Within hospitals, opioid prescribing rates varied more than threefold between high- and low-intensity prescribers (20.8% vs. 6.4%, p < 0.001; Table 2). This difference persisted across multiple pre-specified patient subgroups classified by primary diagnosis during the ED visit or prior comorbidity. For example, among patients with a primary ED diagnosis of back pain, opioid prescribing rates varied from 47.1 to 14.6% between high- and low-intensity prescribers and from 16.0 to 4.4% for patients with a history of serious mental illness (Table 2). There were also persistent differences in patterns of opioid prescribing across patients’ pain severity ratings (Fig. 2). Within each pain score, physicians in higher prescribing quartiles were substantially more likely to prescribe opioids. For example, high-intensity prescribers provided opioids to 10.8% of patients with a pain score of 1 (4.2% of the sample), whereas low-intensity prescribers provided opioids to 2.6% of this group. For patients with a pain score of 10 (6.6% of the sample), the opioid prescribing rates were 43.0% versus 18.0%, respectively.

Rates of opioid prescribing by patient’s self-reported pain score on an 11-point scale from 0 to 10 for index emergency department (ED) visits, stratified by the within-facility quartile of ED providers’ opioid prescribing rate. The 4th, or highest quartile is black, 3rd quartile is dashed purple, 2nd quartile is dashed yellow, and 1st, or lowest, quartile is dotted red. Pain score was missing for 11.4% of visits, in the following distribution by quartile: 1st (lowest quartile), 13%; 2nd quartile, 10%; 3rd quartile, 11%; and 4th (highest) quartile, 11%.

The probability of long-term opioid use was higher among Veterans treated by high- versus low-intensity prescribers (1.39% vs. 1.26%; unadjusted odds ratio [OR] 1.11, 95% CI 1.01–1.21, p = 0.03; Table 2 and Fig. 3). The magnitude of this effect and level of statistical significance remained stable after adjustment for patient characteristics (adjusted OR 1.13, 95% CI 1.02–1.26, p = 0.02), though after controlling for the ED visit primary diagnosis, the p value for the effect was above the conventional threshold for statistical significance (adjusted OR 1.11, 95% CI 0.997–1.24, p = 0.056; online Appendix Table 1 and Fig. 3). The difference in the proportion of patients with any day of opioid fills with > 100 MME between patients treated by high versus low prescribers (0.59% vs. 0.52%, respectively) was not statistically significant in either unadjusted or adjusted analyses (online Appendix Table 1).

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for long-term opioid use, according to treatment by high-intensity or low-intensity opioid prescriber. All unadjusted odds ratios were estimated with the use of bivariate logistic regression with the occurrence of long-term opioid use as the dependent variable and exposure to a high-intensity provider as the key explanatory variable. Adjusted multivariable models adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, depression, anxiety, substance use disorder, serious mental illness, pain diagnoses, number of Charlson chronic conditions (0, 1, 2, 3+), census region, and primary ED diagnosis CCS category (13 categories, see Table Figure 3 contains poor-quality and small text inside the artwork. Please do not re-use the file that we have rejected or attempt to increase its resolution and re-save. It is originally poor; therefore, increasing the resolution will not solve the quality problem. We suggest that you provide us the original format. We prefer replacement figures containing vector/editable objects rather than embedded images. Preferred file formats are .eps, .ai, .tiff, and .pdf.I've included the original PDF for your use. I submitted a modified figure based on the JGIM submission guidelines, which I agree results in low quality images. 1 ). We accounted for grouping of patients within facility with the use of robust standard errors clustered at the facility level and used multiple imputation (10 imputations) for ethnicity/race (2.5% missing) and gender (0.001% missing) using chained equations.

When examining pre-specified patient subgroups, the risk of long-term opioid use from high-intensity prescriber exposure was most prominent for patients with back pain (adjusted OR 1.25, 95% CI 1.01–1.55, p = 0.04) or a musculoskeletal pain diagnosis (adjusted OR 1.21, 95% CI 1.03–1.43, p = 0.03) and for those with a history of depression (adjusted OR 1.28, 95% CI 1.08–1.51, p = 0.004; online Appendix Table 2 and Fig. 3). Almost all other subgroups had point estimates suggesting higher risk of long-term use associated with exposure to high-intensity prescribers, but the estimates did not reach statistical significance. All subgroup estimates remained stable or had larger odds ratios after multivariable adjustment.

Examining patterns of ED visit and hospital utilization in the year subsequent to the index ED visit, we found no evidence for differences in the rates of overall ED visits or potential opioid-related hospital encounters (online Appendix Table 3).

DISCUSSION

In a national sample of Veterans managed within the largest integrated health care system in the nation, we found over threefold variation in the rates of opioid prescribing by ED physicians within the same facility regardless of patients’ presenting severity of pain or primary diagnosis. Patients treated by providers with higher rates of opioid prescribing within their facility had slightly higher rates of long-term opioid use over the subsequent year than those treated by lower prescribing physicians. Controlling for a robust set of patient and ED visit characteristics had little impact on the point estimate of this effect, though after controlling for ED visit characteristics, the estimate no longer met the conventional threshold for statistical significance in the overall sample. However, it did remain statistically significant in patients presenting to the ED with back pain, depression, or a musculoskeletal pain diagnosis.

Compared with the findings from a similarly designed study among Medicare patients, the estimated magnitude and statistical significance of the association between long-term opioid use and exposure to a high-intensity prescriber were both weaker in this analysis. In the Medicare study, the association had an adjusted odds ratio of 1.30 versus 1.13 for Veterans in this study (not adjusting for visit diagnosis for comparison with the Medicare study).12 We were able to address some limitations in the Medicare analysis; for example, we were able to attribute opioid prescriptions directly to individual ED physicians based on the VA’s unified electronic medical record system rather than attribute all outpatient opioids in the week following the ED visit to the ED provider, as was done previously. In addition, we were able to adjust for history of substance use disorder, which was not done in the Medicare analyses because of claims redaction.

We found that high-intensity prescribers were more likely to prescribe opioids across the entire spectrum of pain intensity (or conversely, low-intensity physicians were less likely to use opioids across the entire spectrum). One might have expected that opioid treatment rates would converge across physicians at the highest levels of self-reported pain, when opioids are presumably the most likely choice for pain management, but this was not the case. This finding suggests that the individual discretion of a physician plays a large role in the likelihood of who receives opioids among patients with similar self-reported pain intensity. The recent lackluster performance of opioids versus non-opioids for acute pain in randomized controlled trials further complicates the clinical challenges of how and when to use opioids effectively.23, 24

There are multiple possible reasons why we observed a weaker effect for exposure to high-intensity prescribers in the VA than in the Medicare population. One potential explanation is differences in the characteristics of Veterans and Medicare beneficiaries. For example, there was a higher prevalence of depression in the Medicare cohort (39.5%) than in this study (21.9%), a condition associated with higher rates of conversion to long-term use in this analysis. Another possibility is that, unlike Medicare, the VA is an integrated health system with a unified electronic health record. For patients to progress to long-term opioid use, they need to receive follow-up opioid prescriptions from other providers—we speculate that the more integrated nature of the VA could enable providers to avoid unnecessarily prolonged opioid treatment.

Despite the weaker overall effect of high-intensity prescribers on long-term use, certain patient subgroups appeared more susceptible to long-term use. In particular, the strongest relationship between prescribing and long-term use was present in patients presenting with back pain or with a prior history of depression. These associations are consistent with a number of studies finding that back pain and depression are strong risk factors for progression to chronic opioid use.15, 25,26,27,28 Together with prior evidence, these results suggest that physicians may want to counsel patients with either back pain or a history of depression that they may have a higher risk of a long-term course with opioid use.

This study has important limitations. First, there is the concern for selection bias in this observational study. We assessed the sensitivity of our results by controlling for a broad range of patient and visit factors, which did not meaningfully change our point estimates for the main results of the analysis. It is reassuring that the point estimate of our effects does not appear to be strongly driven by the small differences in observable characteristics that we see between patients treated by high- versus low-intensity providers. However, we cannot exclude unobserved confounding influencing our results. Second, this study was performed in a specific sample of opioid-naïve Veterans, so it may not generalize to other populations. Third, our exposure measure is based on the ED physician opioid prescribing rate, as in the original study, and does not account for duration or quantity of treatment prescribed, which could impact long-term use. Fourth, the data we examined are several years old at this time, which could limit their relevance to prescribing in 2018 and beyond. The time period was chosen to replicate the Medicare study. Finally, we were not able to capture prescriptions filled by Veterans outside the VA, which could impact our definition of “opioid naïve,” assessment of opioid prescriptions prior to inclusion and our outcome measurement, leading to underestimates of long-term opioid use; however, this measurement error is likely non-differential for patients seen by high- versus low-intensity physicians.

In conclusion, in a national sample of opioid-naïve Veterans treated in VA, we found over threefold variation in opioid prescribing rates among ED providers in the same facility. Though the increase in long-term opioid use among patients treated by the highest prescribing providers was not statistically significant in the overall sample, there were significant increases in long-term opioid use among important patient subgroups, including patients with back pain, musculoskeletal pain, or depression. In comparison with prior work, our results suggest that the magnitude of risk of long-term use following exposure to a high-intensity prescriber may depend on the nature of the population or health system studied.

References

Hedegaard H, Miniño AM, Warner M. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2017, NCHS Data Brief, no 329. 2018;(Accessed 4 March 2019 at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db329.htm)

Targeting The Opioid Drug Crisis: A Health And Human Services Initiative. Health Aff. (Millwood). (Accessed March 4, 2019 at http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2015/04/03/targeting-the-opioid-drug-crisis-a-health-and-human-services-initiative/)

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Behavioral Health Coordinating Committee. Addressing prescription drug abuse in the United States: current activities and future opportunities. 2014;(Accessed 4 March 2019 at https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/hhs_prescription_drug_abuse_report_09.2013.pdf)

Muhuri PK, Gfroerer JC, Christine Davies M. Associations of Nonmedical Pain Reliever Use and Initiation of Heroin Use in the United States. 2013;(Accessed 4 March 2019 at https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/DR006/DR006/nonmedical-pain-reliever-use-2013.htm)

National Institute on Drug Abuse. Prescription opioid use is a risk factor for heroin use. (Accessed 4 March 2019 at https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/relationship-between-prescription-drug-heroin-abuse/prescription-opioid-use-risk-factor-heroin-use)

Barnett ML, Gray J, Zink A, Jena AB. Coupling Policymaking with Evaluation — The Case of the Opioid Crisis. N Engl J Med 2017;377(24):2306–9.

Veterans Face Greater Risks Amid Opioid Crisis. FRONTLINE. (Accessed 4 March 2019 at https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/veterans-face-greater-risks-amid-opioid-crisis/)

Seal KH, Shi Y, Cohen G, et al. Association of Mental Health Disorders With Prescription Opioids and High-Risk Opioid Use in US Veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan. JAMA 2012;307(9):940–7.

Bohnert ASB, Ilgen MA, Galea S, McCarthy JF, Blow FC. Accidental poisoning mortality among patients in the Department of Veterans Affairs Health System. Med Care 2011;49(4):393–6.

Brat GA, Agniel D, Beam A, et al. Postsurgical prescriptions for opioid naive patients and association with overdose and misuse: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2018;360:j5790.

Shah A. Characteristics of Initial Prescription Episodes and Likelihood of Long-Term Opioid Use — United States, 2006–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66. (Accessed 4 March 2019 at https://www.facebook.com/CDCMMWR )

Barnett ML, Olenski AR, Jena AB. Opioid-Prescribing Patterns of Emergency Physicians and Risk of Long-Term Use. N Engl J Med 2017;376(7):663–73.

Hastings SN, Smith VA, Weinberger M, Schmader KE, Olsen MK, Oddone EZ. Emergency department visits in Veterans Affairs medical facilities. Am J Manag Care 2011;17(6 Spec No.):e215–223.

Gundlapalli AV, Jones AL, Redd A, et al. Characteristics of the Highest Users of Emergency Services in Veterans Affairs Hospitals: Homeless and Non-Homeless. Stud Health Technol Inform 2017;238:24–7.

Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain. JAMA 2016;315(15):1624–45.

Jena AB, Goldman D, Weaver L, Karaca-Mandic P. Opioid prescribing by multiple providers in Medicare: retrospective observational study of insurance claims. BMJ 2014;348:g1393.

Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol 2011;173(6):676–82.

Davis MA, Lin LA, Liu H, Sites BD. Prescription Opioid Use among Adults with Mental Health Disorders in the United States. J Am Board Fam Med 2017;30(4):407–17.

Abuse NI on D. Part 1: The Connection Between Substance Use Disorders and Mental Illness. (Accessed 4 March 2019 at https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/common-comorbidities-substance-use-disorders/part-1-connection-between-substance-use-disorders-mental-illness)

HCUP-US Tools & Software Page. Accessed 4 March 2019 at https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp

White H. A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica 1980;48:817–38.

Azur MJ, Stuart EA, Frangakis C, Leaf PJ. Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations: What is it and how does it work? Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2011;20(1):40–9.

Chang AK, Bijur PE, Esses D, Barnaby DP, Baer J. Effect of a Single Dose of Oral Opioid and Nonopioid Analgesics on Acute Extremity Pain in the Emergency Department: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2017;318(17):1661–7.

Friedman BW, Dym AA, Davitt M, et al. Naproxen With Cyclobenzaprine, Oxycodone/Acetaminophen, or Placebo for Treating Acute Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2015;314(15):1572–80.

Sun EC, Darnall BD, Baker LC, Mackey S. Incidence of and Risk Factors for Chronic Opioid Use Among Opioid-Naive Patients in the Postoperative Period. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176(9):1286–93.

Boscarino JA, Rukstalis M, Hoffman SN, et al. Risk factors for drug dependence among out-patients on opioid therapy in a large US health-care system: Risk factors for drug dependence among out-patients. Addiction 2010;105(10):1776–82.

Sullivan MD, Edlund MJ, Fan M-Y, DeVries A, Brennan Braden J, Martin BC. Risks for possible and probable opioid misuse among recipients of chronic opioid therapy in commercial and medicaid insurance plans: The TROUP Study. PAIN 2010;150(2):332–9.

Webster BS, Verma SK, Gatchel RJ. Relationship between early opioid prescribing for acute occupational low back pain and disability duration, medical costs, subsequent surgery and late opioid use. Spine 2007;32(19):2127–32.

Funding

This study is financially supported by a grant from VA Health Services Research & Development (HSR&D) I01 HX001765-01 to Dr. Gellad.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This study was approved by the institutional review board at the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Barnett receives consulting fees unrelated to this work from Greylock McKinnon Associates Inc. and serves as a paid expert witness for plaintiffs in lawsuits against opioid manufacturers and distributors. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to disclose.

Disclaimer

This work represents the opinions of the authors alone and does not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the National Institute on Aging, or the US Government.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 94 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Barnett, M.L., Zhao, X., Fine, M.J. et al. Emergency Physician Opioid Prescribing and Risk of Long-term Use in the Veterans Health Administration: an Observational Analysis. J GEN INTERN MED 34, 1522–1529 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05023-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05023-5