Abstract

Purpose

Relapse after complicated intra-abdominal infection (cIAI) remains common after treatment. The optimal antibiotic treatment duration for cIAIs is uncertain, especially in cases where source control is not achieved. We hypothesised that in patients with cIAIs, regardless of source control intervention, there would be a lower relapse rate with long-course antibiotics (28 days) compared with short course (≤ 10 days). We piloted a trial comparing ≤ 10-day with 28-day antibiotic treatment for cIAI.

Methods

A randomised controlled unblinded feasibility trial was conducted. Eligible participants were adult patients with a cIAI that were diagnosed ≤ 6 days prior to screening. Randomisation was to long-course (28 days) or short-course (≤10 days) antibiotic therapy. Choice of antibiotics was determined by the clinical team. Participants were followed up for 90 days. Primary outcomes were willingness of participants to be randomised and feasibility of trial procedures.

Results

In total, 172 patients were screened, 84/172 (48.8%) were eligible, and 31/84 (36.9%) were randomised. Patients were assigned to either the short-course arm (18/31, 58.0%) or the long-course arm (13/31, 41.9%). One patient in the short-course arm withdrew after randomisation. In the short-course arm, 4/17 (23.5%) were treated for a cIAI relapse vs 0/13 (0.0%) relapses in the long-course arm. Protocol violations included deviations from protocol-assigned antibiotic duration and interruptions to antibiotic therapy.

Conclusions

This feasibility study identified opportunities to increase recruitment in a full trial. This study demonstrates completion of a randomised controlled trial to further evaluate if the optimum antibiotic duration for cIAIs is feasible.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03265834

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Complicated intra-abdominal infections (cIAIs) extend beyond the hollow viscus of origin into the peritoneal space and are associated with either abscess formation or peritonitis.1 They are heterogeneous in aetiology and include spontaneous infections arising from a perforated intra-abdominal viscus, and post-operative infections. Despite the varied origin of these infections, there are similar management strategies that centre on source control, e.g. drainage of intra-abdominal fluid collections, and administration of antibiotic therapy. These infections are challenging to manage, in part due to the varied pathology that causes them, and are associated with significant morbidity and mortality.2, 3 Despite this burden of disease, there is little clinical evidence on which to base antibiotic treatment. At present, there have been two trials into antibiotic durations for cIAI. The STOP-IT trial,4 which compared 4 vs. 8 days (median durations) and found that longer durations significantly reduced the time until relapse (p = < 0.001). The DURAPOP trial compared 8 to 15 days duration and found a lower rate of clinical failure in patients with the longer-course antibiotics, 24% (28/120) with 8 days and 14% (16/116) with 15 days (p = 0.54).5 Given that there remains a high relapse rate, it has been suggested that longer courses of antibiotics may reduce relapse of cIAIs.6 In the UK, for serious infections (brain abscess, mastoiditis, septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, lung abscess, endocarditis and prostatitis) which have a high risk of relapse and associated mortality, microbiologists often recommend up to and beyond 4 weeks of antibiotic therapy. This approach has not yet been investigated in a RCT for cIAIs. Furthermore, around 30% of patients in England and Scotland do not undergo source control procedures,7 and thus far, there have been no trials evaluating antibiotic duration in this patient group. We therefore hypothesise that in patients with cIAIs, regardless of source control intervention, there will be a lower relapse rate when treated with 28 days of antibiotics compared with ≤ 10 days of antibiotics.

Materials and Methods

Trial Design

An unblinded parallel group randomised controlled feasibility trial comparing long-course (28 days) to short-course (≤ 10 days) antibiotic therapy in patients with cIAI was carried out. This feasibility trial was approved by the Yorkshire and Humber (Leeds–East) Research Ethics Committee, UK (16/YH0453) (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03265834). The study is reported according to the CONSORT extension to pilot and feasibility trials, see supplementary material.

Participants

Participants were eligible if they were aged ≥ 18 years old and had been diagnosed with a cIAI. The diagnostic criteria for a cIAI diagnosis included the presence of both radiological and clinical features consistent with a cIAI, including a fever (temperature of ≥ 38 °C) and a neutrophilia (> 7.5 × 10*9/L) or intra-operative confirmation of an abscess. Any cIAI diagnosed >6 days prior to screening was excluded. Patients were identified either by notification by a member of the patient’s clinical team to the research team or by screening of radiology reports. Participants were excluded if their cIAI was associated with uncomplicated appendicitis, primary complicated appendicitis, pancreatitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, primary (spontaneous) bacterial peritonitis (SBP), continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis peritonitis (CAPD peritonitis) and Clostridium difficile infection as they were considered distinct conditions with separate management strategies. Patients were recruited from Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS trust in the UK between August 2017 and June 2018. The trial was stopped at the end of funding for the trial research staff.

Interventions

Participants received either ≤ 10 days (short course (SC)) or 28 days (long course (LC)) of antibiotic therapy. The clinical team caring for the patient determined the choice of antibiotic, as the aim was to compare antibiotic prescribing strategies (i.e. short course vs long course) rather than individual drugs or specified combinations of drugs. The antibiotic prescribed was chosen according to the available clinical and microbiological data, in conjunction with local antibiotic guidelines, and altered as new results and clinical information become available.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes were to determine trial feasibility and included the willingness of participants to be randomised, the willingness of clinicians to allow patients to be recruited, the number of eligible patients and follow-up rates. Additionally, data on clinical objectives that would be the primary and secondary objectives for a definitive study following on from the feasibility study were collected in order to determine the feasibility of collecting this information. These clinical objectives included rate of relapse, mortality, total days of antibiotic consumption, all infections within 90 days of cIAI diagnosis, length of hospital stay and number of source control procedures required. Participants were followed up for 90 days, and outcomes were assessed at 30 days and 90 days post cIAI diagnosis (via telephone consultation or inpatient review).

Relapse of cIAI was defined as relapse of infection occurring after surgical and antibiotic therapy to manage the primary CABI had been considered successful (as demonstrated by antibiotics being stopped and no further source control procedures planned). Relapse of cIAI included both definite and probable cases. A definite case was defined as cIAI relapse with a combination of radiological and clinical features consistent with CABI including a fluid collection, a temperature of ≥ 38 degrees, and a neutrophilia (neutrophil count > 7.5 × 109/L) or intra-operative confirmation of an abscess. Probable cIAI relapse included cases where there was either absence of radiological imaging or radiological features inconsistent with a cIAI, but where no other source of infection was identified, and the patient was managed for a relapsed cIAI.

Quality of life was assessed with the European Quality of Life–5 Dimensions 3-level questionnaire (EQ-5D-3L) and the EQ-5D visual-analogue scale (EQ-5D VAS) at baseline, day 30, day 90 and the time of cIAI relapse.

Sample Size

Given that this was a feasibility study, no formal sample size calculation was performed and a maximum patient recruitment target of 60 patients was set.8

Randomisation

Patients in each intervention arm were stratified into two groups: post-operative cIAIs (cIAI within 90 days of surgery) and non-post-operative cIAIs (primary cIAIs). Simple randomisation with a 1:1 allocation ratio was then used to allocate patients.

Sequence Generation

A web-based sequence generator was used to generate an unpredictable allocation sequence (https://www.random.org/sequences/).

Allocation Concealment

An independent person outside of the research team transferred the sequence into sealed envelopes, which were then accessed after trial enrolment to allocate participants to a treatment arm.

Implementation

Patient’s allocation was determined by a trial researcher (SA, RP, & RB) after a patient had given their consent.

Blinding

Patients, researchers and clinicians were not blinded to the treatment allocation.

Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistics were used to report outcomes and baseline characteristics. Continuous data are summarised as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR), and categorical data were summarised as proportions (percentage). For clinical outcome analysis, intention to treat analysis was completed. Sub-group analysis of post-operative cIAIs vs non-post-operative cIAIs was also completed. All analyses were conducted using the statistical package SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0, IBM Corp).

Protocol Amendments

One protocol amendment was made and implemented during the study, and the substantial changes included the following: The exclusion of any patients who had a cIAI in the previous 1 year was changed to 3 months to allow inclusion of more patients with cIAIs. The definition of cIAI was amended to include patients with fever prior to admission and patients who have evidence of purulent peritonitis intra-operatively. An amendment that was approved but not implemented was for the recruitment of patients via consultee consent.

Results

Participant Flow

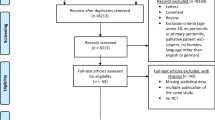

From August 2017 to June 2018, 172 patients were assessed for eligibility, 84/172 (48.8%) were eligible for enrolment, and 31/84 (36.9%) were enrolled and randomised. Eighty-eight patients were ineligible, of whom 42 (47.7%) were being treated for a cIAI but did not have a fever and a raised neutrophil count and 14 (15.9%) patients were ineligible because they had > 6 days of antibiotics for their cIAI. Of the 53/84 (63.1%) patients who were eligible but not enrolled; 32 declined participation (Table 1),13 were either discharged or had antibiotics discontinued before consent or approach by the research team, two were not enrolled at the request of the treating surgeon, two died prior to approach and four were not recruited for other reasons (one patient was non-english speaking, one was breastfeeding, one was due to undergo major surgery for another indication and one was unable to be followed up due to travel outside of the continent). Patients who declined to participate in the study were more likely to have had a HDU/ICU admission (13.3% of patients who consented to participate had a HDU/ICU admission vs 25.0% of patients who declined to participate). Reasons for declining to participate included a preference for an antibiotic duration (4/32), feeling too unwell (4/32), concern over adverse events (3/32), but most commonly, no reason was given (20/32). One patient withdrew from the study after randomisation, the remaining 30/31 randomised patients were followed up for the complete study period. Participant flow is outlined in the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram in Fig. 1.

Protocol Adherence

Participants were deemed to have received allocated treatment if in the SC arm they received < 10 days (+ 1) and in the LC arm 28 days (± 1). In the SC treatment arm, 4/17 (24%) patients continued antibiotics for longer than the allocated duration, two received 14-day treatment and two received 12-day treatment. Whereas, 5/13 (38%) patients in the LC treatment arm did not receive the allocated treatment duration of antibiotics; one patient discontinued early at day 20 due to a serious adverse event (SAE) from amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (deranged liver function tests), three patients had their antibiotics stopped early (days 4, 5 and 15) inadvertently by members of the clinical team who were unaware of treatment allocation and one patient continued antibiotics for 30 days.

Baseline Data

The baseline characteristics of patients enrolled in the study are summarised in Table 2. Characteristics of patients in each arm of the study were comparable apart from the number of patients with post-operative cIAIs, which was higher in the short-course arm (59% vs 31%).

Numbers Analysed, Outcomes and Estimations

Intention to Treat Analysis

Overall, 4/30 (13.3%) patients had either a definite or probable cIAI relapse, all of whom were randomised to receive short-course antibiotics.

Only one patient died during the study; this patient was randomised to receive 28 days of antibiotics; however, treatment was stopped early on day four of treatment. The overall hospital stay was 8 days (IQR 4.5–11) in patients who had long-course antibiotics and 9 days (IQR 4.5–31) in patients who had short-course antibiotics. A higher proportion of patients in the SC arm had other infection diagnoses during the follow-up period compared with the LC arm (6/17 (35.3%) vs 1/13 (7.9%)). Clinical outcomes are shown in Table 3, and characteristics by presence or absence of relapse are shown in Table 4.

Sub-Group Analysis

In total, 14/30 (46.7%) patients had a post-operative cIAI (cIAI within 90 days of abdominal surgery). Of these, four received long-course antibiotics and ten short-course antibiotics. Out of the four patients who had a cIAI relapse, three had post-operative cIAIs.

Quality of Life Analysis

In total, 26/30 participants completed EQ-5D-3L and EQ-VAS questionnaires for all timepoints. For the baseline assessments, data on 1/30 EQ-5D-3L and 2/30 EQ-VAS were missing. One patient died before day 30 assessments took place, and 1/29 day 30 EQ-VAS and 1/29 day 90 EQ-VAS were missing. All four patients who had a cIAI relapse completed a EQ-5D-3L and EQ-VAS questionnaires at the time of cIAI relapse.

Source Control Procedures

Overall, eight patients did not undergo source control procedures. Six patients in the SC arm did not undergo source control; three of these patients had post-operative cIAIs, two had complicated diverticular disease and one had perforated peptic ulcer. Two patients in the LC arm did not undergo source control; both had cIAI due to complicated diverticulitis.

Of the 11/13 patients who had source control in the LC arm, three had percutaneous drainage and eight had surgical procedures (four had resection with anastomosis or closures and four had resection with proximal diversion). In the SC arm, 7/17 had percutaneous drainage and 4/17 had surgical source control (one had surgical drainage, one had closure of perforation with a washout and two had surgical resection with proximal diversion).

Antibiotic Treatment

The median antibiotic treatment duration was 9 days (IQR 7.5–11.5) in the group of patients receiving SC antibiotics and 28 days (IQR 17.5–28.0) in the group receiving LC antibiotics. The most frequently used intravenous antibiotic regimen was cefuroxime and metronidazole, which was used in 14/30 (46.7%) participants (6 patients in LC arm and 8 patients in SC). Piperacillin-tazobactam was the second commonest antibiotic regimen and used in 7/30 (23.3%) patients (6 patients in the SC and 1 in the LC arm). Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid was the most frequently used oral regimen in 13/30 (43.3%) patients (6 in the SC arm and 7 in the LC arm). Two patients out of the 13 patients in the SC arm had interruptions to their antibiotic course (antibiotics stopped and restarted); this led to one patient receiving antibiotics for longer than the assigned duration. Overall, seven patients had their initial antibiotic regimen altered due to the presence of resistant organisms: 3/11 (27.2%) in the LC arm and 4/16 (25.0%) in the SC arm.

Harms

One SAE related to the study occurred in a patient allocated to receive LC who developed deranged liver function tests (LFTs), which normalised after cessation of antibiotics. Other SAEs that occurred which were unrelated to the study procedures included small-bowel obstruction secondary to adhesions, stroke, acute kidney injury, episode of uncomplicated diverticulitis and pulmonary embolus. There were no episodes of Clostridium difficile infection.

Discussion

The optimal antibiotic treatment strategy for cIAIs remains uncertain especially in cases where it is not feasible to perform source control. To date, there have been two RCTs which have evaluated antibiotic duration for cIAIs where source control has been achieved. The STOP IT trial reported that in patients who had adequate source control, short-course antibiotic therapy (median 4 days) was as effective as long-course therapy (median 8 days).4 The DURAPOP trial assessed antibiotic duration for intensive care patients and compared 8 days to 15 days of antibiotic therapy.5 The primary outcome was antibiotic-free days within the 45 days after source control, and results favoured 8 days of treatment (median number of antibiotic-free days 15 (6–20) vs 12 (6–13) days). However in both trials, clinical failure was common (15–24%). One reason for relapse of cIAI may be that antibiotic treatment may not have been given for long enough to eradicate bacteria from, what should be, a sterile intra-abdominal cavity. Thus, long-course antibiotic therapy may reduce the rate of cIAI relapse.

This RCT of short-course (≤ 10 days) or long-course (28 days) antibiotic therapy for cIAIs was designed to determine the feasibility of conducting a definitive RCT. An adequate proportion (36.7%) of eligible patients were enrolled which suggests that it would be feasible to enrol patients into such a definitive trial. Additionally, with the exception of two cases, clinicians were willing for patients to be recruited, and patients were able to successfully complete follow-up. Whilst our recruitment target of 60 patients was not reached, we recruited sufficient patients to be able to determine trial feasibility.

During the trial, there were minimal data missing on primary and secondary outcome measures, with the exception of EQ-5D questionnaires. However, the rate of missing data was low; therefore, using EQ-5D questionnaires to calculate QALYs for economic evaluation will still be feasible in a definitive trial. Overall, protocol adherence was 70%, in keeping with other trials that dictate antibiotic duration; protocol adherence was 82% in the experimental group and 72.7% in the control group in the STOP IT trial, 79% and 82% in the two arms in the DURAPOP trial.4, 5 Non-adherence was mostly associated with antibiotics durations being outside accepted ranges; extending these beyond 24 h would increase adherence and not detract from the overall treatment allocations.

We identified aspects of the protocol that reduced recruitment. The definition of cIAI used in this study was more inclusive than recommended definitions, as it allowed surgeons to make a diagnosis of cIAI without operative evidence, thus allowing inclusion of patients who do not undergo a source control procedure.9 However, the definition used for cIAI in this trial excluded 48% of patients who were treated for cIAI because they did not have both a recorded fever (≥ 38 °C) and a neutrophilia (> 7.5 × 10*9/L). In a definitive trial, a more pragmatic definition should be adopted to ensure that evidence is gained for a more representative population of patients treated for cIAI. Additionally, it was noted that other infections, e.g. urinary tract or respiratory tract infection, not including cIAI relapses, were common, and consideration to these being included within a primary outcome measure in a definitive trial would be needed.

This study was not designed to detect a clinically significant difference in the secondary outcomes; however, we found that relapses predominantly occurred in patients who had post-operative cIAIs who received short-course antibiotics. Thus, supporting further research into our hypothesis that longer antibiotic durations may reduce relapse rates.

Complicated intra-abdominal infections continue to be associated with significant morbidity and mortality. This trial demonstrates the feasibility of a substantive RCT to further investigate antibiotic durations for the management of cIAIs.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Solomkin, J.S., et al., Diagnosis and management of complicated intra-abdominal infection in adults and children: guidelines by the Surgical Infection Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis, 2010. 50(2): p. 133–64.

Brun-Buisson, C., et al., Incidence, risk factors, and outcome of severe sepsis and septic shock in adults. A multicenter prospective study in intensive care units. French ICU Group for Severe Sepsis. JAMA, 1995. 274(12): p. 968–74.

DeFrances, C.J., K.A. Cullen, and L.J. Kozak, National Hospital Discharge Survey: 2005 annual summary with detailed diagnosis and procedure data. Vital Health Stat 13, 2007(165): p. 1–209.

Sawyer, R.G., et al., Trial of short-course antimicrobial therapy for intraabdominal infection. N Engl J Med, 2015. 372(21): p. 1996–2005.

Montravers, P., et al., Short-course antibiotic therapy for critically ill patients treated for postoperative intra-abdominal infection: the DURAPOP randomised clinical trial. Intensive Care Med, 2018. 44(3): p. 300–310.

Wenzel, R.P. and M.B. Edmond, Antibiotics for abdominal sepsis. N Engl J Med, 2015. 372(21): p. 2062–3.

Ahmed S and the CABI Collaborative, Clinical Management of Complicated Intra-abdominal Infections in the United Kingdom, in 28th European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. 2018: Madrid, Spain.

Billingham, S.A., A.L. Whitehead, and S.A. Julious, An audit of sample sizes for pilot and feasibility trials being undertaken in the United Kingdom registered in the United Kingdom Clinical Research Network database. BMC Med Res Methodol, 2013. 13: p. 104.

Nystrom, P.O., et al., Proposed definitions for diagnosis, severity scoring, stratification, and outcome for trials on intraabdominal infection. Joint Working Party of SIS North America and Europe. World J Surg, 1990. 14(2): p. 148–58.

Acknowledgements

Caroline Bedford, Lead Pharmacist for Clinical Trials, Leeds Teaching Hospitals Trust; Catherine Moriarty, Senior Research Sister, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust; Sarah Brown, Medical Statistician, The University of Leeds; Shafaque Shaikh, University of Aberdeen at NHS Grampian.

Funding

Dr. Ahmed was awarded a 1-year clinical research fellowship by Leeds Cares, a charity based at Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, UK.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception, design, material preparation, data collection and analysis. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Shadia Ahmed, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 37 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmed, S., Brown, R., Pettinger, R. et al. The CABI Trial: an Unblinded Parallel Group Randomised Controlled Feasibility Trial of Long-Course Antibiotic Therapy (28 Days) Compared with Short Course (≤ 10 Days) in the Prevention of Relapse in Adults Treated for Complicated Intra-Abdominal Infection. J Gastrointest Surg 25, 1045–1052 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-020-04545-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-020-04545-2