Abstract

Background

Percutaneous cholecystostomy is frequently used as a treatment option for acute calculous cholecystitis in patients unfit for surgery. There is sparse evidence on the long-term impact of cholecystostomy on gallstone-related morbidity and mortality in patients with acute calculous cholecystitis. This study describes the long-term outcome of acute calculous cholecystitis following percutaneous cholecystostomy compared to conservative treatment.

Methods

This was a cohort study of patients admitted at our institution from 2006 to 2015 with acute calculous cholecystitis without early or delayed cholecystectomy. Endpoints were gallstone-related readmissions, recurrent cholecystitis, and overall mortality.

Results

The investigation included 201 patients of whom 97 (48.2%) underwent percutaneous cholecystostomy. Patients in the cholecystostomy group had significantly higher age, comorbidity level, and inflammatory response at admission. The median duration of catheter placement in the cholecystostomy group was 6 days. The complication rate of cholecystostomy was 3.1% and the mortality during the index admission was 3.5%. The median follow-up was 1.6 years. The rate of gallstone-related readmissions was 38.6%, and 25.3% had recurrence of cholecystitis. Cox regression analyses revealed no significant differences in gallstone-related readmissions, recurrence of acute calculous cholecystitis, and overall mortality in the two groups.

Conclusions

Percutaneous cholecystostomy in the treatment of acute calculous cholecystitis was neither associated with long-term benefits nor complications. Based on the high gallstone-related readmission rates of this study population and todays perioperative improvements, we suggest rethinking the indications for non-operative management including percutaneous cholecystostomy in acute calculous cholecystitis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cholecystectomy is the recommended treatment for acute calculous cholecystitis (ACC).1 However, in elderly and comorbid patients, many clinicians esteem that this group of patients is better off with conservative treatment with or without percutaneous cholecystostomy (PC), due to assumed increased perioperative morbidity and mortality. Meanwhile, PC is time- and resource-demanding compared to sole antibiotic treatment. It impairs patient mobilization and requires a dedicated radiologist for the procedure, a follow-up antegrade cholangiography, and multiple daily flushing of the catheter.

PC was recommended in the Tokyo Guideline of 2007 and 2013 though with limited evidence in patients with severe acute cholecystitis, organ failure, and need for intensive care, In addition, PC has been suggested as a treatment option in moderate cholecystitis as bridge to surgery.2,3 According to the latest Tokyo guideline of 2018, the recommended treatment of severe ACC is early laparoscopic cholecystectomy. In lack of an experienced surgeon or if the patient is unfit for surgery, the recommendation still is urgent biliary drainage followed by laparoscopic cholecystectomy, once the patient condition has improved.1 PC is considered a safe procedure with complication rates at 0–16%.4,5,6,7,8,9 As the main cause of ACC is obstruction of the cystic duct by gallstones, it may seem more efficient to catheter the gallbladder empyema, compared to exclusive antibiotic treatment. However, the literature is sparse with only one published randomized clinical trial, allocating 123 high-risk patients to either conservative treatment with antibiotics or antibiotics in combination with PC. No difference was found in morbidity or mortality between the two groups after a 12-month follow-up.10 A matched comparative study found that patients undergoing PC were more comorbid and had higher associated mortality than patients treated with cholecystectomy.9

At our surgical department, we frequently use PC for the conservative treatment of ACC due to the tradition and easy access, thus giving us the opportunity to investigate if PC compared with non-operative management for ACC influences the long-term risk of gallstone-related morbidity and mortality.

Materials and Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study of long-term outcomes in patients with ACC without early or delayed cholecystectomy during first admission and treated with or without PC at the Digestive Disease Center, Bispebjerg Hospital, University of Copenhagen from 1st of January 2006 to 31st of December 2015. The minimal follow-up period was 12 months after the index admission. The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (ref. j.nr. 2012-58-0004).

Study Population

All medical charts from patients discharged with a diagnosis code for acute cholecystitis (DK80/DK81) according to the International Classification for Diseases (WHO-ICD10) were reviewed. Patients who did not meet the diagnostic criteria were excluded, as were patients with pancreatic-biliary malignancies or acalculous cholecystitis. In this study, we compared the clinical course after treatment with- or without PC. In order to have a long follow-up of patients with gallbladders in situ treated for ACC, we excluded those patients who underwent early cholecystectomy or went uneventfully to delayed cholecystectomy 3 months after their first presentation of ACC during the study period.

Data collected for each patient included baseline patient demographics and comorbidity as reflected by the American Society of Anesthesiology classification system (ASA) and the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI). We also assessed details from index admission including vital signs, systemic inflammatory markers (leucocytes and C-reactive protein), duration of cholecystitis symptoms, length of stay, duration of cholecystostomy catheter placement and antibiotic treatment, catheter-associated complications within 30 days, and medical complications. Medical complications were defined as any adverse event requiring additional treatment or prolonging hospital stay. Definitions of exposure variables at baseline are reported in Table 1.

Patients were followed until gallstone-related readmission, death, or loss to follow-up. Gallstone-related readmissions were defined as admissions due to biliary colics, acute cholecystitis, choledocholithiasis with or without pancreatitis, or gallstone ileus occurring later than 30 days after the index admission. Readmissions were recorded only for the Capital Region of Denmark. At follow-up, we checked the national central registration office, and if the patient had moved out of the region, the follow-up period ended at that time, and the patient was considered lost to follow-up concerning readmissions. Date of death was recorded from the national central registration office.

The main explorative variable was PC versus no-PC. Endpoints were defined as readmissions related to gallstones, readmissions due to recurrence of ACC, and overall mortality.

Diagnosis and Treatment Algorithm

The diagnosis of ACC was based on the presence of abdominal pain in the right upper quadrant and a positive Murphy’s sign with systemic signs of inflammation and possibly radiologic findings according to the Tokyo Guideline 2013 criteria.11 According to the local guideline, all patients with onset of symptoms ≤ 5 days were offered emergency cholecystectomy. The remaining patients were treated with- or without PC. The indication for PC was at the discretion of the surgeon. PC was performed under ultrasound guidance and local anesthesia. In all cases, the radiologist placed a transperitoneal 5.7-Fr pigtail catheter (TCD Single Step, Argon Medical Devices, Inc., Texas, USA) into the gallbladder. The catheter was fixed to the skin and flushed with saline 3–6 times a day. No catheters were placed through the liver. Following PC, an antegrade cholangiography through the catheter was routinely performed after 4–6 days. The catheter was removed if there was passage of contrast to the duodenum.

The standard regimen of antimicrobial therapy was a combination of intravenous metronidazole and cephalosporin or piperacillin/tazobactam. When patient condition improved, metronidazole and a fluorquinolone were orally administered. Antibiotic treatment was not administered in patients with mild ACC.12

Only younger (< 80 years of age) patients fit for surgery were offered cholecystectomy 3 months after the index admission.

Statistical Analysis

Medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) and numbers with percentages were reported for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Wilcoxon signed-rank test and Chi square test were used for descriptive purposes to identify differences in baseline variables between the PC and no-PC groups with level of significance defined as a p value less than 0.05. Unadjusted cumulative incidence proportions were reported with death as the competing outcome and patients alive or lost to follow-up censored on last date available. Cox regression was used for inferential statistical analyses. Hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were reported, and significant associations were defined by a confidence interval not including one. Analysis of endpoints was performed with PC as a binary variable (PC/no-PC) where the no-PC group was considered reference. Statistical estimates were reported as multiple adjusted models to adjust for confounding. Possible confounding variables at baseline were identified in the descriptive statistical analyses. A minimum of ten outcome events per parameter was required in the multiple adjusted models. Scaled Schoenfeld residuals were used to test goodness of fit in the most adjusted models. The assumption of proportional hazards was not violated in any of the analyses. All statistical analyses were performed with the “R Studio” software (RStudio Inc., Boston, MA) with the “survival” and “cmprsk” packages. The study is reported according to the STROBE guideline for observational studies.13

Results

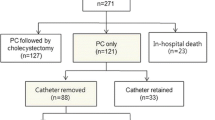

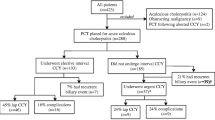

A total of 1170 patients were discharged with a diagnosis of acute cholecystitis during the study period. One hundred and twenty-five patients did not meet the diagnostic criteria, 22 had acalculous cholecystitis, 819 underwent early or delayed cholecystectomy, and three were excluded because of pancreato-biliary malignancy. The final study population comprised 201 patients (Fig. 1) who were admitted with ACC and did not undergo emergent or delayed cholecystectomy. One hundred forty-one patients (74.1%) were included because of comorbidity and 33 patients (16.4%) would not consent to emergent cholecystectomy in spite of young age and low perioperative risk. Four patients (2%) were lost to follow-up for readmission of which three were tourists and one had moved from the region. The follow-up time for readmissions was median 1.61 years (IQR 0.24–3.29).

Ninety-seven (48.3%) patients were treated with PC and were significantly older and more comorbid than the 104 patients in the no-PC group. Moreover, they revealed an increased inflammatory response at admission as compared with the no-PC group (Table 1). In the PC group, 93.8% were treated with antibiotics as compared with 83.7% in the no-PC group (p = 0.044). In both groups, the median duration of symptoms of ACC prior to admission were about 3.0 days. The PC catheters were placed median 1 day (IQR 1.0–2.0) after hospital admission. The median duration of PC was 6.0 days. There were no significant differences in rates of medical complications or mortality during the index admission between the two groups (Table 2). Seven patients (3.5%) died during the index admission. An 87-year old man died of grade 3 cholecystitis with a liver abscess. The remaining six patients died from myocardial infarction, stroke, respiratory insufficiency due to pneumonia, congestive heart failure, hepatocellular carcinoma, and end-stage myelodysplastic syndrome in combination with ACC, respectively. The PC group had a longer hospital stay than the no-PC group (median 9.0 days (IQR 7.0–12.0) versus 4.0 days (IQR 2.0–6.0), p < 0.0001). We found multiple catheter dislocations, but placement of a new PC was only indicated in three cases (7.2%). There were only three (3.1%) severe complications to PC (bile leak, n = 1 and abscess, n = 2). There were no complications in the patients where the catheter was dislocated and taken out before time.

During long-term follow-up, 70 patients (34.8%) were readmitted with gallstone-related symptoms (Table 3). The majority of readmissions occurred within the first 3 years, and the cumulative incidence for all readmissions was 38.6% (Fig. 2). Five patients (5.2%) were readmitted with complications to PC; three with abscess and two with a cholecystocutaneous fistula. Another patient from the PC group was readmitted at 11 months of follow-up with recurrent cholecystitis and had an emergency laparoscopic cholecystectomy due to perforated cholecystitis.

Significant differences in age, ASA score, heart rate, CRP, and antibiotic treatment were identified between the PC and no-PC groups at baseline and were therefore adjusted for in Cox regression multiple models. In both age- and multiple-adjusted models, we found no significant differences for readmissions between the two groups (Table 4).

There was a cumulative incidence proportion of 25.3% for recurrence of ACC. No significant differences between the PC and the no-PC groups were found in age- and multiple-adjusted models (Table 4).

The overall mortality during follow-up was 71.6%. Two patients died during the readmission due to choledocholithiasis with cholangitis and respiratory insufficiency following emergency cholecystectomy on the indication of ACC (Table 3). The disease-specific mortality during readmission was 2.9%. Age- and multiple-adjusted models revealed no significant differences in overall mortality between the two groups (Table 4).

Discussion

This retrospective cohort study was conducted to investigate if PC as compared with no-PC for the treatment of patients with ACC and without indication for surgery was associated with a more favorable clinical long-term outcome. We found no difference in the long-term risk of gallstone-related readmission, recurrence of ACC, or overall mortality between these two treatment algorithms. Surprisingly, we found a high rate of gallstone-related readmissions in both groups. In resemblance with other series, there were few short-term complications related to the PC, but the PC group had longer hospital stay. Two patients were readmitted with secretion from a cholecystocutaneous fistula. Their preceding cholangiography had demonstrated an open cystic duct, and the PC catheter had been removed on days 3 and 5, respectively.

We could not investigate if there was an immediate benefit of PC on pain as well as prevention of gallbladder necrosis, perforation, or abscess formation. Several studies report a dramatic response in pain relief and decrease of CRP within 2–3 days after PC,7,14,15 but the only randomized study comparing PC to antibiotic treatment reports comparable levels of symptoms in both groups at 72 h.10

The strengths of this study include an almost complete long-term follow-up of the population based on register data including the entire Capital Region of Denmark. Such comprehensive follow-up is rarely seen in studies performed in other countries. Some limitations need to be addressed. First, it is a single-center study. Second, due to the retrospective and non-randomized study design, the decision to perform PC or antibiotic treatment only instead of cholecystectomy was at the discretion of the surgeon. No sample size calculations were performed due to the retrospective study design but since the confidence intervals in the regression analyses were close to one, the risk of type 2 error is considered very low. Based on the differences in baseline characteristics, we may suspect a selection bias in choosing PC to the patients with more advanced levels of ACC, comorbidity, and age. The significant difference in initiating antibiotic treatment in the two groups (PC 93.8% and no-PC 83.7%) supports the difference in severity of ACC. This limitation was addressed through adjustment in multiple models. However, a risk of residual confounding may still be present. Randomized controlled trials should be performed to fully address these limitations.

After patients had recovered from their first attack of ACC, more than one out of three were readmitted with gallstone-related morbidity and one out of four developed recurrent ACC. To our surprise, the assumption that the elderly and comorbid patients will die before experiencing further gallstone events requiring hospitalization, was wrong in more than one third of cases. This emphasizes cholecystectomy as the only curative treatment for ACC, and our findings also indicate that there has been—at least in our department—a tendency to treat too many patients with PC. Several reviews also support early laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the elderly and/or comorbid patients.16,17 A recent meta-analysis including 337, 500 critically ill patients with ACC treated either with cholecystectomy or PC showed a significant difference in favor of cholecystectomy regarding length of hospital stay, readmissions for biliary complaints, and mortality.17 However, there was no difference in complications or re-interventions in the two groups in the meta-analysis.16 Recent advances in laparoscopic techniques and perioperative care have changed the indication for surgery in the elderly patients in general. These findings are reflected by a decline in mortality rates after cholecystectomy in the elderly from 12% before 1995 to 4% after 1995.16 In a large retrospective study of 703 patients with ACC treated with early cholecystectomy, no statistically significant difference in 30-day mortality in two age groups (3% (≥ 75 years) versus 1% (< 75 years), p = 0.07) was found.18 Although cholecystectomy in the elderly patients is associated with a higher conversion rate (18% vs. 5%) and longer postoperative length of stay (5 days vs. 3 days),18 curative surgical treatment for ACC for this patient group is still considered indicated by many. There are currently two ongoing randomized clinical trials addressing acute cholecystectomy versus non-operative management. In a Dutch multicenter trial (CHOCOLATE), high-risk patients with ACC are randomly allocated to laparoscopic cholecystectomy or PC.19 In a Finnish multicenter trial, patients with ACC and above 80 years of age are randomized to cholecystectomy or antibiotic treatment.20 Hopefully, these studies will clarify the superior treatment for ACC in the elderly and comorbid patients.

Conclusion

The present study failed to demonstrate a long-term clinical benefit from the use of PC in high-aged comorbid patients with ACC. Because gallstone-related readmission rates were high and perioperative care has been improved, we suggest that PC should not be used routinely in the management of ACC. Ongoing and future randomized clinical trials may contribute further to optimized treatment algorithm for ACC.

References

Okamoto K, Suzuki K, Takada T, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018 flowchart for the management of acute cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2017. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhbp.516.

Itoi T, Tsuyuguchi T, Takada T, et al. TG13 indications and techniques for biliary drainage in acute cholangitis (with videos). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2013; 20: 71–80.

Yamashita Y, Takada T, Kawarada Y, et al. Surgical treatment of patients with acute cholecystitis: Tokyo guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2007; 14: 91–7.

Atar E, Bachar GN, Berlin S, et al. Percutaneous cholecystostomy in critically ill patients with acute cholecystitis: Complications and late outcome. Clin Radiol 2014; 69: e247–52.

Horn T, Christensen SD, Kirkegård J, Larsen LP, Knudsen AR, Mortensen F V. Percutaneous cholecystostomy is an effective treatment option for acute calculous cholecystitis: A 10-year experience. HPB (Oxford) 2015; 17: 326–31.

Zerem E, Omerović S. Can percutaneous cholecystostomy be a definitive management for acute cholecystitis in high-risk patients?. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutaneous Tech 2014; 24: 187–91.

Granlund A, Karlson BM, Elvin A, Rasmussen I. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous cholecystostomy in high-risk surgical patients. Langenbeck’s Arch Surg 2001; 386: 212–7.

Sanjay P, Mittapalli D, Marioud A, White RD, Ram R, Alijani A. Clinical outcomes of a percutaneous cholecystostomy for acute cholecystitis: A multicentre analysis. Hpb 2013; 15: 511–6.

Smith TJ, Manske JG, Mathiason MA, Kallies KJ, Kothari SN. Changing trends and outcomes in the use of percutaneous cholecystostomy tubes for acute cholecystitis. Ann Surg 2013; 257: 1112–5.

Hatzidakis AA, Prassopoulos P, Petinarakis I, et al. Acute cholecystitis in high-risk patients: Percutaneous cholecystostomy vs conservative treatment. Eur Radiol 2002; 12: 1778–84.

Yokoe M, Takada T, Strasberg SM, et al. TG13 diagnostic criteria and severity grading of acute cholecystitis (with videos). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2013; 20: 35–46.

Mazeh H, Mizrahi I, Dior U, et al. Role of antibiotic therapy in mild acute calculus cholecystitis: A prospective randomized controlled trial. World J Surg 2012;36:1750–59.

STROBE statement - Checklist of items that should be included in reports of observational studies (STROBE Initiative). Int J Public Health 2008; 53: 3–4.

Boland GW, Lee MJ, Leung J, Mueller PR. Percutaneous cholecystostomy in critically ill patients: Early response and final outcome in 82 patients. Am J Roentgenol 1994; 163: 339–42.

van Overhagen H, Meyers H, Tilanus HW, Jeekel J, Laméris JS. Percutaneous cholecystectomy for patients with acute cholecystitis and an increased surgical risk. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 1996; 19: 72–6.

Winbladh A, Gullstrand P, Svanvik J, Sandström P. Systematic review of cholecystostomy as a treatment option in acute cholecystitis. HPB (Oxford) 2009; 11: 183–93.

Ambe PC, Kaptanis S, Papadakis M, Weber SA, Jansen S, Zirngibl H. The treatment of critically Ill patients with acute cholecystitis. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2016; 113: 545–51.

Loozen CS, Van Ramshorst B, Van Santvoort HC, Boerma D. Early cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis in the elderly population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig. Surg 2017; 34: 371–9.

Kortram K, van Ramshorst B, Bollen TL, et al. Acute cholecystitis in high risk surgical patients: percutaneous cholecystostomy versus laparoscopic cholecystectomy (CHOCOLATE trial): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2012; 13: 7.

Paajanen H. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy or conservative treatment in the acute cholecystitis of the elderly patients. November 25, 2016. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02972944?term=paajanen&rank=7. Accessed September 07, 2018

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Stine Ydegaard Turiño, Daniel Mønsted Shabanzadeh, Lars Tue Sørensen, Lars Nannestad Jørgensen: Conception or design of the work.

Stine Ydegaard Turiño, Daniel Mønsted Shabanzadeh, Nethe Malik Eichen, Stine Lundgaard Jørgensen: Acquisition, analysis of the work.

Stine Ydegaard Turiño, Daniel Mønsted Shabanzadeh, Lars Nannestad Jørgensen: Interpretation of data for the work.

Stine Ydegaard Turiño, Daniel Mønsted Shabanzadeh, Nethe Malik Eichen, Stine Lundgaard Jørgensen, Lars Tue Sørensen, Lars Nannestad Jørgensen: Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

Stine Ydegaard Turiño, Daniel Mønsted Shabanzadeh, Nethe Malik Eichen, Stine Lundgaard Jørgensen, Lars Tue Sørensen, Lars Nannestad Jørgensen: Final approval of the version to be published.

Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: Stine Ydegaard Turiño, Daniel Mønsted Shabanzadeh, Nethe Malik Eichen, Stine Lundgaard Jørgensen, Lars Tue Sørensen, Lars Nannestad Jørgensen.

Corresponding author

Additional information

This study was delivered as an oral presentation at the Annual Meeting of the Danish Surgical Society, 10 November 2017, Copenhagen.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Turiño, S.Y., Shabanzadeh, D.M., Eichen, N.M. et al. Percutaneous Cholecystostomy Versus Conservative Treatment for Acute Cholecystitis: a Cohort Study. J Gastrointest Surg 23, 297–303 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-018-4021-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-018-4021-5