Abstract

Background and Purpose

Publications document the risk of developing esophageal stricture as a sequential complication of esophageal injury grades 2b and 3a. Although there are studies describing the risk factors of post-corrosive stricture, there is limited literature on these factors. The aim of this study was to evaluate the different factors with post-corrosive esophageal stricture and non-stricture groups in endoscopic grades 2b and 3a of corrosive esophageal injuries.

Methods

Data were retrospectively analyzed in the patients with esophageal injury grades 2b and 3a between January 2011 and December 2017.

Results

One hundred ninety-six corrosive ingestion patients were admitted with 32 patients (15.8%) in grade 2b and 12 patients (6.1%) in grade 3a and stricture was developed in 19 patients (61.3%) with grade 2b and in 10 patients (83.3%) with grade 3a. The patients’ height of the non-stricture group was greater than that of stricture groups (2b stricture group, 1.58 ± 0.08 m; 2b non-stricture group, 1.66 ± 0.07 m; p < 0.004; 3a stricture group, 1.52 ± 0.09 m; 3a non-stricture group, 1.71 ± 0.02 m; p < 0.001). Omeprazole was more commonly used in the non-stricture than stricture group (26.3% in the 2b stricture group, 69.2% in the 2b non-stricture group, p = 0.017; 50% in the 3a stricture group, 100% in the 3a non-stricture group, 1.71 ± 0.02 m, p = 0.015).

Conclusions

The height of patients may help to predict the risks and the prescription of omeprazole may help to minimize the risks of 2b and 3a post-corrosive esophageal stricture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Ingestion of corrosive agents remains an important public health problem worldwide, especially in developing countries including Thailand.1,2,3,4,5,6 Corrosive ingestion in children is primarily accidental and is observed most commonly in children, whereas adults are more often intentional and suicidal.1,7,8 Acidic and alkaline substances may cause serious injuries in the esophagus.5,9 Acids cause coagulation necrosis, whereas alkalis combine with tissue proteins and cause liquefaction necrosis which penetrates deep into tissues.10,11

Endoscopy is the cornerstone of management of caustic injuries. It is recommended for performance early after ingestion. Esophageal injuries are graded according to the Zargar classification.12,13 Endoscopic classification of post-corrosive esophageal injuries is crucial information for diagnosis, patients’ prognosis, and appropriate treatment. The treatment strategies for patients with esophageal injuries grades 0 to 2a are of a conservative nature which give good results without developing early and/or late complications. The 3b and esophageal perforation groups are considered for intensive care treatment with aggressive surgical management. For esophageal injuries grades 2b and 3a, the published data on the risk of developing esophageal stricture as a sequential complication is evident.4,5,10,11,14,15 Esophageal stricture is an interesting topic in which factors and preventive methods are often debated. Although there are studies describing the risk factors of post-corrosive esophageal injuries and strictures, there is limited literature on 2b and 3a groups.5,12,16 The aim of this study was to report our clinical experience and to evaluate the different factors with post-corrosive esophageal stricture and non-stricture groups in endoscopic grades 2b and 3a of corrosive esophageal injuries.

Patients/Material and Methods

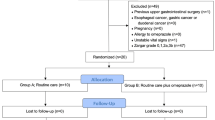

We conducted a retrospective study with patients who were consulted and referred to our Department of Surgery with corrosive ingestion between January 2011 and December 2017. Data was identified in the hospital electronic documentation system. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed by experienced surgeons within 24 h of ingestion and the endoscopic findings of esophageal injuries classified using Zargar classification13 (Table 1). Patients with esophageal injuries grades 2b and 3a who were admitted, treated, and followed up at Thammasat University Hospital were enrolled to this study. The patients with grades 0 to 2a who received conservative treatment, and patients with grade 3b and 4 lesions who were managed by intensive care and surgical intervention, were excluded from this report.

The patient characteristics, type of corrosive substance, causes, treatments, and outcomes were analyzed and compared between esophageal stricture and non-stricture groups. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean. Statistical analysis was performed using the χ2 test and Fisher’s test for categorical data and the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous data. All data were analyzed with SPSS v.22.0 data (Statistical Package for Social Sciences, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A p value < 0.005 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

During a 6-year period, 196 patients were admitted to Thammasat University Hospital with corrosive ingestion; 44 patients with esophageal injuries grades 2b and 3a were enrolled in this study that was composed of 32 patients (15.8%) in grade 2b and 12 patients (6.1%) in grade 3a of total corrosive ingestion patients. The patients with esophageal injuries who developed stricture were 61.3% in the grade 2b group and 83.3% in the grade 3a group. For esophageal injuries grade 2b, 19 patients in the stricture group (2b stricture group) and 13 patients in the non-stricture group (2b non-stricture group) were not different by age, gender makeup, body weight, or BMI (body mass index) (Table 2). For esophageal injuries grade 3a, 10 patients in the stricture group (3a stricture group) and 2 patients in the non-stricture group (3a non-stricture group) were not different by age, body weight, or BMI. Female patients were predominant in esophageal injuries 2b and 3a in this study except that all patients in the 3a non-stricture group were male (Table 3). Both 2b and 3a esophageal injury patients’ height of non-stricture groups was greater than that of stricture groups (2b stricture group, 1.58 ± 0.08 m; 2b non-stricture group, 1.66 ± 0.07 m; p < 0.004; 3a stricture group, 1.52 ± 0.09 m; 3a non-stricture group, 1.71 ± 0.02 m; p < 0.001). An alkaline substance showed predominantly in both groups of stricture patients (13 patients (68.4%) in the 2b stricture group, 3 patients (23.1%) in the 2b non-stricture group, p = 0.009; 6 patients (60%) in the 3a stricture group, no one in the 3a non-stricture group, p = 0.005).

The white blood cell count of 2b and 3a esophageal injury patients was not different between stricture and non-stricture groups. All the patients with 2b and 3a corrosive esophageal injuries were treated with antibiotic. Steroid treatment was applied to 2b corrosive esophageal injuries and 3a stricture group and the results demonstrated no difference in both stricture and non-stricture patients. The proton-pump inhibitor used in our study was omeprazole which appeared to be more prescribed in the non-stricture than stricture group (26.3% in the 2b stricture group, 69.2% in the 2b non-stricture group, p = 0.017; 50% in the 3a stricture group, 100% in the 3a non-stricture group, 1.71 ± 0.02 m, p = 0.015) (Tables 4 and 5).

After admission, the length of hospital stay was not different between stricture and non-stricture groups. The study data of corrosive esophageal injuries showed no other complications such as bleeding, perforation, and mortality in any patients.

Discussion

Foregut corrosive ingestion is a little-understood public health problem with a small number of publications. The extent of destruction depends on the physical form, type, amount and concentration of substance, contact duration, and the primary tissue of the target organ. Acidic substances cause coagulation necrosis, with eschar formation that may limit substance penetration and injury depth.10 On the other hand, alkaline substances can combine with tissue proteins and cause liquefactive necrosis with saponification and penetrate deeper into the gastrointestinal organ layers. High viscosity alkali may increase severity of esophageal injury by increasing contact time.11

Despite the use of CT scan for corrosive severity assessment, early endoscopic examination is still the crucial option for evaluation and guidance for further individual patient management. The optimal timing of endoscopy to define the degree of injuries following the endoscopic classification described by Zargar et al.13 showed the relation to sequence of corrosive esophageal injuries and treatment regimens. Many studies indicate that post-corrosive esophageal stricture is one important complication.2,4,5,12 The corrosive esophageal injuries grades 0 to 2a were treated successfully with conservative treatment without stricture sequelae. For corrosive esophageal injuries grade 3b, the international guidelines and publications recommend intensive care and aggressive surgical treatment.4,12,17 From reports on patients with corrosive esophageal injuries grades 2b and 3a who bear a risk of post-corrosive esophageal stricture, the choices of management and treatment are still discussed and debated.4,5,10,11,14,15 We have been interested in these two groups and have analyzed our data to evaluate the factors that may affect post-corrosive esophageal stricture and non-stricture groups with grading as 2b and 3a.

Contini S et al. published 71% esophageal stricture developed by grade 2b5 and Lu LS et al. reported grade 3 as the major risk factor of post-corrosive esophageal stricture that showed 58.6% stricture followed grade 3 corrosive esophageal injuries.18 Le Naoures P et al. suggested the physician’s attention to a high risk of esophageal stricture with > 2a grade esophagitis of early endoscopic examination.19 In our experience, we had 15.8% patients with corrosive esophageal injuries grade 2b and 6.1% in grade 3a of total corrosive ingestion patients during a 6-year period. After treatment, the patients developed post-corrosive esophageal stricture 61.3% in grade 2b and 83.3% in grade 3a.

For the corrosive esophageal injuries grade 2b, the patient characteristics showed no difference by age, sex, body weight, BMI, and suicidal/accidental cause in stricture and non-stricture groups. In the next group, grade 3a, the patient characteristics exhibited no difference by age, body weight, BMI, and suicidal/accidental cause but 2 non-stricture patients were an all-male group. The non-stricture patients were significantly taller than stricture patients in both post-corrosive esophageal injuries grades 2b and 3a. We postulate that the taller person has a larger size of esophagus that may present less luminal area contact to a corrosive substance resulting in fewer stricture sequelae.

Ingested alkaline substances significantly dominated in both groups of stricture patients due to the process of liquefactive necrosis and deeper penetration into the esophageal wall. Data of the two groups on admission course and hospitalization showed no difference. Other complications and mortality were not detected in either group. Blood examination for white blood cell count could not predict the stricture consequence.

The role of antibiotic and steroid is still under debate.5,12 All patients with corrosive esophageal injuries grades 2b and 3a were treated initially intravenously with antibiotic. The administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics was usually treated with corticosteroids until oral intake was resumed. The steroid and antibiotic were administered orally for a total of 3 weeks until the patient investigated with upper GI study for stricture evaluation. For the patient without steroid, the intravenous administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics was administrated and stopped after endoscopic evaluation except the patient with lung injury. The use of steroid treatment was also not different between stricture and non-stricture groups.

In this study, the use of proton-pump inhibitor was not compulsory. Nevertheless, both grade 2b and 3a groups with non-stricture result received omeprazole much more frequently than the stricture patients with a statistical significance. The omeprazole was prescribed to the patients with history or symptoms of dyspepsia, heartburn, gastritis, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), or gastric ulcer that currently use and continue in the corrosive situation. In cases that did not received PPI before, the omeprazole was prescribed with the reasons to minimize the effect of gastric reflux to grade 2b and 3a esophagitis that may be decreasing the post-corrosive esophageal stricture, fasten of mucosal healing, and prevent stress ulcer. Currently, the efficacy of proton-pump inhibitors in minimizing esophageal injury has not been proven. An experimental study of omeprazole with corrosive esophageal burn was available.20 Our findings support this animal model study and is in concordance with another clinical study that reported omeprazole may effectively be used in the acute-phase treatment of caustic esophageal injuries.21 Omeprazole is known to function not only as a proton-pump inhibitor but has also been reported for selective acceleration of apoptotic cancer cell death, inhibition of tumorigenesis, acceleration of microvascular and connective tissue regeneration, increase of fibroblast growth factor, inhibition of myofibroblasts change, enhancement of catalase activity, and inhibition of neutrophil infiltration and oxidative tissue damage.22,23,24,25,26,27 Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects may be beneficial in the healing process of post-corrosive esophageal injuries and sequential stricture.

In this study, the corrosive esophageal injuries grades 2b and 3a are the important groups of patients that are at risk of post-corrosive esophageal stricture. Alkalis play the major role for stricture sequelae. The age of patient, sex, body weight, BMI, cause of corrosive ingestion (suicidal/accidental), and white blood cell count could not help to predict the risk of post-corrosive esophageal stricture. The short height of the patient may be one of the factors that the surgeon has to awareness with post-corrosive esophageal stricture. For the steroid treatment, it could not prevent situation of post-corrosive esophageal stricture. Although the number of patients in this study is still small, this may give us an early conclusion that the prescribing of omeprazole may be of benefit to minimize the risks of post-corrosive esophageal stricture. Further studies are required to evaluate and confirm that the patient height can predict the risks and the proton-pump inhibitors can reduce the risks of grade 2b and 3a corrosive esophageal injury patients developing post-corrosive esophageal stricture.

References

Havanond C. Clinical features of corrosive ingestion. J Med Assoc Thai. 2003;86(10):918–24.

Awsakulsutthi S, Havanond C. A retrospective study of anastomotic leakage between patients with and without vascular enhancement of esophageal reconstructions with colon interposition: Thammasat University Hospital experience. Asian J Surg. 2015;38(3):145–9.

Havanond C, Havanond P. Initial signs and symptoms as prognostic indicators of severe gastrointestinal tract injury due to corrosive ingestion. J Emerg Med. 2007;33(4):349–53.

Havanond C. Is there a difference between the management of grade 2b and 3 corrosive gastric injuries? J Med Assoc Thai. 2002;85(3):340–4.

Contini S, Scarpignato C. Caustic injury of the upper gastrointestinal tract: a comprehensive review. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(25):3918–30.

Are’valo-Silva C, Eliashar R, Wohlgelernter J, Elidan J, Gross M. Ingestion of caustic substances: a 15-year experience. Laryngoscope. 2006;116(8):1422–6.

Pace F, Antinori S, Repici A. What is new in esophageal injury (infection, drug-induced, caustic, stricture, perforation)? Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2009;25(4):372–9.

Hugh TB, Kelly MD. Corrosive ingestion and the surgeon. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;189(5):508–22.

Goldman LP, Weigert JM. Corrosive substance ingestion: a review. Am J Gastroenterol 1984;79:85–90.

Zargar SA, Kochhar R, Nagi B, Mehta S, Mehta SK. Ingestion of corrosive acids. Spectrum of injury to upper gastrointestinal tract and natural history. Gastroenterology. 1989;97(3):702–7.

Zargar SA, Kochhar R, Nagi B, Mehta S, Mehta SK. Ingestion of strong corrosive alkalis: spectrum of injury to upper gastrointestinal tract and natural history. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87(3):337–41.

Bonavina L, Chirica M, Skrobic O, Kluger Y, Andreollo NA, Contini S, et al. Foregut caustic injuries: results of the world society of emergency surgery consensus conference. World J Emerg Surg. 2015;10:44.

Zargar SA, Kochhar R, Mehta S, Mehta SK. The role of fiberoptic endoscopy in the management of corrosive ingestion and modified endoscopic classification of burns. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37(2):165–9.

Cabral C, Chirica M, de Chaisemartin C, Gornet JM, Munoz-Bongrand N, Halimi B, et al. Caustic injuries of the upper digestive tract: a population observational study. Surg Endosc. 2012;26(1):214–21.

Alipour Faz A, Arsan F, Peyvandi H, Oroei M, Shafagh O, Peyvandi M, et al. Epidemiologic Features and Outcomes of Caustic Ingestions; a 10-Year Cross-Sectional Study. Emerg (Tehran). 2017;5(1):e56.

Ramasamy K, Gumaste VV. Corrosive ingestion in adults. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;37(2):199–24.

Javed A, Pal S, Krishnan EK, Sahni P, Chattopadhyay TK. Surgical management and outcomes of severe gastrointestinal injuries due to corrosive ingestion. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;4(5):121–5.

Lu LS, Tai WC, Hu ML, Wu KL, Chiu YC. Predicting the progress of caustic injury to complicated gastric outlet obstruction and esophageal stricture, using modified endoscopic mucosal injury grading scale. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:919870.

Le Naoures P, Hamy A, Lerolle N, Métivier E, Lermite E, Venara A. Risk factors for symptomatic esophageal stricture after caustic ingestion-a retrospective cohort study. Dis Esophagus. 2017;30(6):1–6.

Topaloglu B, Bicakci U, Tander B, Ariturk E, Kilicoglu-Aydin B, Aydin O, et al. Biochemical and histopathologic effects of omeprazole and vitamin E in rats with corrosive esophageal burns. Pediatr Surg Int. 2008;24(5):555–60.

Cakal B, Akbal E, Köklü S, Babalı A, Koçak E, Taş A. Acute therapy with intravenous omeprazole on caustic esophageal injury: a prospective case series. Dis Esophagus. 2013;26(1):22–6.

Arisawa T, Harata M, Kamiya Y, Shibata T, Nagasaka M, Nakamura M, et al. Is omeprazole or misoprostol superior for improving indomethacin-induced delayed maturation of granulation tissue in rat gastric ulcers? Digestion. 2006;73(1):32–9.

Biswas K, Bandyopatdhyay U, Chattopadyay I, Varadaraj A. A novel antioxidant and anti-apoptotic role of omeprazole to block gastric ulcer through scavenging of hydroxyl radical. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(13):10993–1001.

Kil BJ, Kim IW, Shin CY, Jeong JH, Jun CH, Lee SM, et al. Comparison of IY81149 with omeprazole in rat reflux oesophagitis. J Auton Pharmacol. 2000;20(5–6):291–6.

Kim YJ, Lee JS, Hong KS, Chung JW, Kim JH, Hahm KB. Novel application of proton pump inhibitor for the prevention of colitis-induced colorectal carcinogenesis beyond acid suppression. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2010;3(8):963–74.

Kobayashi T, Ohta Y, Inui K, Yoshino J, Nakazawa S. Protective effect of omeprazole against acute gastric mucosal lesions induced by compound 48/80, a mast cell degranulator, in rats. Pharmacol Res. 2002;46(1):75–84.

Pozzoli C, Menozzi A, Grandi D, Solenghi E, Ossiprandi MC, Zullian C, et al. Protective effects of proton pump inhibitors against indomethacin-induced lesions in the rat small intestine. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2007;374(4):283–91.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank staff members of Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Thammasat University, for the data of this study and special thanks to Norman Mangnall for assistance in editing the English version of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All of the author and co-author listed: Prasit Mahawongkajit, Prakitpunthu Tomtitchong, Nuttorn Boochangkool, Palin Limpavitayaporn, Amonpon Kanlerd, Chatchai Mingmalairak, Surajit Awsakulsutthi, and Chittinad Havanond, followed the guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE); all of the author listed in this manuscript met the four criteria of the guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mahawongkajit, P., Tomtitchong, P., Boochangkool, N. et al. Risk Factors for Esophageal Stricture in Grade 2b and 3a Corrosive Esophageal Injuries. J Gastrointest Surg 22, 1659–1664 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-018-3822-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-018-3822-x