Abstract

Li3V2(PO4)3 glass-ceramic nanocomposites, based on 37.5Li2O-25V2O5-37.5P2O5 mol% glass, were successfully prepared via heat treatment (HT) process. The structure and morphology were investigated by X-ray diffraction (XRD) and scanning electron microscope (SEM). XRD patterns exhibit the formation of Li3V2(PO4)3 NASICON type with monoclinic structure. The grain sizes were found to be in the range 32–56 nm. The effect of grain size on the dynamics of Li+ ions in these glass-ceramic nanocomposites has been studied in the frequency range of 20 Hz–1 MHz and in the temperature range of 333–373 K and analyzed by using both the conductivity and modulus formalisms. The frequency exponent obtained from the power law decreases with the increase of temperature, suggesting a weaker correlation among the Li+ ions. Scaling of the conductivity spectra has also been performed in order to obtain insight into the relaxation mechanisms. The imaginary modulus spectra are broader than the Debye peak-width, but are asymmetric and distorted toward the high frequency region of the maxima. The electric modulus data have been fitted to the non-exponential Kohlrausch–Williams–Watts (KWW) function and the value of the stretched exponent β is fairly low, suggesting a higher ionic conductivity in the glass and its glass-ceramic nanocomposites. The advantages of these glass-ceramic nanocomposites as cathode materials in Li-ion batteries are shortened diffusion paths for Li+ ions/electrons and higher surface area of contact between cathode and electrolyte.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Phosphate glasses containing lithium ions have relatively high ionic conductivity, and thus, they can be applied in energy storage devices and solid state batteries [1, 2]. Monoclinic Li3V2(PO4)3 NASICON (Na super ionic conductor) type structure has been proposed as the most promising high-safety cathode materials for rechargeable lithium ion batteries due to its high specific capacity, high operating voltage, and good ion mobility [3–5]. On the other hand, layered intercalation nanocomposites such as vanadium oxide (V2O5) nanocrystalline glass-ceramics have been studied widely due to their applications in several fields such as energy-conversion systems, electrocatalysis, energy-storage applications, sensors, proton-pump electrodes, photochemical redox reactions, and chemiresistive detectors [6–8]. Also, layered V2O5 are appropriate host materials for insertion chemistry because their interlayer spaces in conjunction with their semiconducting properties allow them to work as cathode materials for rechargeable lithium ion batteries, etc. [9].

It has been reported that the alkali glasses and glass-ceramic nanocomposites containing transition metal oxides (TMO) show mixed conductivity. For instance, Na2O–B2O3–V2O5 glasses exhibit both electronic and ionic conductivity contribution [10]. Mixed conductivity was also reported for other glasses, e.g., Li2O-V2O5-TeO2 [11], Na2O-V2O5-TeO2 [12], Li2O-WO3-P2O5 [13], and Na2O-V2O5-P2O5 [14].

Dielectric relaxation spectroscopy has been proven to be a strong technique for investigating the ion conduction mechanisms and relaxation in glasses and glass-ceramic nanocomposites. The frequency-dependent conductivity gives important information on the relaxation of charge carriers in the glasses and glass-ceramic nanocomposites. The necessary features of the ion dynamics may be deduced from the conductivity spectra [15–17]. Another way to enhance materials parameters is to obtain them in nanocrystalline form. The advantages of these nanocomposites are shortened diffusion paths for Li+ ions/electrons and higher surface area which may give higher ionic conductivity [18, 19].

The purpose of this work was to study the effect of grain size on the lithium ion dynamics and conductivity relaxation in 37.5Li2O-25V2O5-37.5P2O5 glass and its glass-ceramic nanocomposites annealed at 450 °C for different times (2, 4, 8, and 24 h), using the impedance spectroscopy. The ac conductivity has been analyzed in the framework of power law conductivity and modulus formalisms. The structure and morphology are investigated by X-ray diffraction (XRD) and scanning electron micrograph (SEM). In general, we focus our attention on enhancement of dynamics for Li-ions in these glass-ceramic nanocomposites.

Experimental

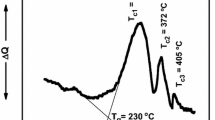

The glass system 37.5Li2O-25V2O5-37.5P2O5 mol% was prepared by mixing specified weights of vanadium oxide (V2O5, purity 99 %, Sigma Aldrich), lithium oxide (Li2O, purity 99 %, Alfa Aesar), and phosphorus oxide (P2O5, purity 99.9 %, Sigma Aldrich). The powder mixture was heated in a platinum crucible at 1050 °C for 20 min. The material at melting point was cast in a stainless steel mold. Following this procedure, we obtained a bulk glass of about 1.5 mm in thickness. The glass-ceramic nanocomposites were prepared by heat treatment (HT) of the abovementioned glass by heating in air after crystallization temperature at 450 °C for 2, 4, 8, and 24 h in air. The samples were checked by X-ray diffraction (Siemens D 6000) using CuKα radiation at 40 kV in the 2θ range from 10° to 60°. Scanning electron microscope (SEM; EVO 40, ZEISS) was utilized to investigate the morphology of the glass-ceramic samples. Complex impedance spectroscopy measurements were taken of about 1-mm-thick samples obtained from the initial rectangular with silver past evenly applied on both sides of the sample for better electrical contact. The sample was then held between two spring-loaded electrodes. The impedance |Z*|, the phase angle θ, the dielectric constant ε′, and the dielectric loss ε″ were measured with MICROTEST 6377 LCR meter in the 20 Hz–1 MHz frequency range at different temperatures.

Results and discussions

X-ray diffraction

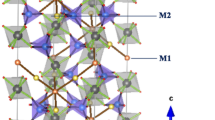

The XRD patterns of the present glass and corresponding glass-ceramic nanocomposites annealed at 450 °C for different times (2, 4, 8, and 24 h) are shown in Fig. 1. As seen in this figure, the glass sample does not exhibit any sharp peaks, which are suggestive of the non-crystalline nature of the materials. The overall features of the glass curve confirm the amorphous nature of the present glass sample. In the case of glass-ceramic nanocomposites, they include a number of peaks corresponding to nanocrystalline phase. The material could be indexed well to monoclinic Li3V2(PO4)3 NASICON type structure with the space group of P21/n (PDF#01-072-7074) [20] and some unknown phases. Generally, several factors can contribute to the broadening of X-ray diffraction peaks. One factor is lattice strain that directly affects the Li3V2(PO4)3 crystallite [21, 22]. The average grain sizes (D) of glass-ceramic nanocomposites were calculated according to the following [23]:

where K ≈ 0.9, λ = 0.15406 nm is the wavelength of Cukα radiation, є is the lattice strain, B is the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the most intense peak, and θ is the Bragg angle of the X-ray diffraction peak. The induced strain in powders due to crystal defect and distortion was calculated by the following [24]:

The variation of grain sizes and lattice strain of the present glass-ceramic nanocomposites as a function of HT time is shown in Fig. 2. It is observed that the grain size values are between 32 and 56 nm. These results agreed with the results obtained by TEM images in our recent paper [25]. The sample annealed at 450 °C for 4 h exhibits the smallest value of grain size, 32 nm. On the other hand, the annealed sample for 2 h exhibits relatively large grain size, 38 nm, and then the grain size decreases to 32 nm for 4 h. However, the grain size increases again to 47 and 56 nm for 8 and 24 h, respectively. This result can be explained by the following: the annealing temperature increases the atomic mobility which enhances the ability of atoms to find the most energetically favorite sites. After that, with increasing of the annealing time, the densities of the crystalline defects including dislocations, vacancies, and interstitials decrease [26]. However, with increase of the annealing time, the nuclei collect together again to form large grains. The lattice strain of the present glass-ceramic nanocomposites is almost the same (≈0.01), suggesting that the crystalline lattice is not distorted with variations of grain size in the resulting Li3V2(PO4)3 crystallite (i.e., the present glass-ceramic nanocomposites have similar lattice structures with variations of grain size in the given Li3V2(PO4)3 crystallite) [27].

Scanning electron microscope

The SEM image and energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectrum of Li3V2(PO4)3 glass-ceramic nanocomposite annealed at 450 °C for 4 h is displayed in Fig. 3. As seen in this figure, the sample revealed the nanostructure consisting of small, non-uniform, and randomly oriented grains, which influence the dynamics properties of Li ions in Li3V2(PO4)3 glass-ceramic. It can be supposed that the enhancement in the dynamics of Li ions and electrochemical properties of this sample is attributed to the intrinsic properties, such as conductivity. In those grains with a relative high surface area, the Li ions have no scatter over greater distance between the surface and center during lithium insertion/extraction [28]. This result illustrated that the heat treatment process can result to relatively high surface area, which may give higher ionic conductivity, larger capacity, and best rate ability. Therefore, this composite can be suitable material for use as cathode in Li-ion batteries or supercapacitors. From the EDX analysis, the present Li3V2(PO4)3 glass-ceramic is composed of P, V, and O elements but the Li element cannot be discovered because of the detection limit of EDX. Similar results were obtained on the other samples.

Impedance spectroscopy

Impedance spectroscopy (IS) is a well-known method for the characterization of dynamics of ions in the present glass and its glass-ceramic nanocomposites annealed at 450 °C for 2, 4, 8, and 24 h. The Nyquist plots (ρ′(ω) vs. ρ″(ω)) for all the samples (see Fig. 4) exhibit two semicircles: one in the high frequency region and the other at lower frequency. According to impedance spectroscopy, this type of behavior can be described by a series combination of two parallel gather RC circuits as shown in the inset of Fig. 4. The first semicircle (R1C1) appears due to the bulk resistance of the sample, and its intersection with the real axis is taken as the resistance of the sample, while the second semicircle (R2C2) appears due to polarization of mobile Li+ ions at the electrode-sample interface [29]. The bulk resistance is an attribute of electronic conduction [30]. It has been reported that the alkali glasses and glass-ceramic nanocomposites containing transition metal oxides (TMO) show mixed conductivity (i.e., both electronic and ionic) [10–14]. The centers of the semicircles are found to be below the real axis. This suggests that the relaxation of ions is non-Debye in nature. While temperature increases, the radius of semicircle, corresponding to the bulk resistance, decreases. It means that the bulk resistance of the sample decreases with increase of temperature and accordingly conductivity increases.

Conductivity formalism

The dc conductivity of the glass and its glass-ceramic nanocomposites annealed at 450 °C for 2, 4, 8, and 24 h was calculated from impedance plots. The reciprocal of the absolute temperature dependence of the dc conductivity for the present glass and its glass-ceramic nanocomposites shown in Fig. 5 is described by Arrhenius relation,

where σ 0 is the pre-exponential factor, E σ is the activation energy for the electrical conduction, and k is Boltzmann’s constant. The activation energies for the electrical conduction, calculated from Eq. (3), are listed in Table 1. The variation of dc conductivity and crystalline size with HT time is illustrated in Table 1. The maximum conductivity and minimum grain size are found for the glass-ceramic nanocomposite with annealing for 4 h. This maximum conductivity may be due to the reducing in grain size. However, the electrical conductivity is influenced by grain boundary dispersing. This grain boundaries work as traps which capture electrons and lead to form a potential barrier. Constructing of a potential barrier at the grain boundaries also causes dispersing of conduction electrons, which leads to decrease the conductivity. Therefore, the increase of the conductivity can be attributed to the reducing in grain boundary dispersing due to the decrease in grain size [31]. From Table 1 also, it is clear that the conductivity tends to be highest when the activation energy is small. On the other hand, the glass-ceramic nanocomposites annealed at 450 °C for 4 h which has the smallest grain size exhibits highest conductivity and smallest activation energy. So these nanocomposites are very important to use as cathode materials in Li-ion batteries or supercapacitors because of shortened diffusion paths for Li+ ions/electrons and higher surface area of contact between electrolyte and cathode. It was also shown that reducing the grain size is important for reaching full capacity [18, 19].

Figure 6 illustrates the frequency dependence of total conductivity for the present glass and its glass-ceramic nanocomposites at different temperatures. The electrical conductivity is characterized by Jonscher’s power law [32]:

where σ(ω) is the total conductivity, σ dc is the dc conductivity, A is the constant, and s is the frequency exponent whose value is between 0 and 1, i.e., 0 < s < 1. From Fig. 6, it is clear that the conductivity increases with increase in frequency. The values of the frequency exponent, s, are calculated from the slopes of log σ ac versus log ω for the present glass and its glass-ceramic nanocomposites. The frequency exponent, s, has been used to describe the electrical conduction mechanism in materials. More information about the conductivity mechanisms are obtained by analyzing the temperature dependence of the frequency exponent, s. The difference of s with temperature is shown in Fig. 7 for the glass and its glass-ceramic nanocomposites. As temperature increase, the value of s decreases. This kind of variation of s with temperature has been observed in some glasses and glass-ceramic nanocomposites [33, 34]. This behavior suggests weaker correlation effects among Li+ ions [15].

The dynamics of charge carriers in the present glass and its glass-ceramic nanocomposites is studied by Almonde-West formula [35],

where ω h is the crossover frequency of the charge carriers. We have calculated the crossover frequency (ω h) by the expression, ω h = (σ dc/A)1/s, and its values for the present glass and its glass-ceramic nanocomposites at fixed temperature (353 K) are listed in Table 2.

The scaling behavior of the conductivity spectra provides a perception into the temperature dependence of the ion dynamics. In this scaling process, the conductivity is scaled by dc conductivity, σ dc, and the frequency axis is scaled by the crossover frequency, ω h, which is expected to be more suitable for scaling the conductivity spectra of ionic conductors. These results at different temperatures for the present glass and its glass-ceramic nanocomposites are shown in Fig. 8. The perfect overlap of these spectra at different temperatures indicates that they obey the time–temperature superposition principle. Here, this suggests that the relaxation dynamics of charge carriers in the present glass and its glass-ceramic nanocomposites is independent of temperature.

Modulus formalism

We have also investigated the ac conductivity of present glass and its glass-ceramic nanocomposites using the modulus formalism. We have used both the conductivity formalism and the modulus formalism because there is a discussion on which of these two formalisms gives a better descriptive of the data analysis [36–38].

The electric modulus M * is defined as the inverse of the complex dielectric constant, ε * [39].

where M′ and M″ are the real and imaginary part of the complex modulus, M *.

Figure 9 exhibits the variation of real and imaginary parts of the electric modulus as a function of frequency for the present glass and its glass-ceramic nanocomposites at different temperatures. From this figure, it is observed that the real part of modulus spectra, M′, exhibits dispersion as the frequency is increased and tends to saturate at M ∞ at higher frequencies. The small value of M′ in the low frequency region facilitates the migration of ion conduction. The imaginary part of modulus spectra, M″, in Fig. 9 shows a single relaxation peak focused at the dispersion region of M′. The M″ curves exhibit a maximum at a distinctive frequency, known as relaxation frequency, f max. The most probable conductivity relaxation time, τ m, can be calculated from (f max = 1/2πτ m) [39]. The values of τ m at 353 K for the present glass and its glass-ceramic nanocomposites are listed in Table 2. From this table, the glass-ceramic nanocomposite annealed at 450 °C for 4 h which has the smallest grain size shows the smallest relaxation time. We also see that the maximum in the imaginary part of electric modulus M″ (M″max) shifts to higher frequency, leading to decrease of relaxation time, with increase in temperature (i.e., as the temperature is increased, the movement of the charge carriers becomes faster). This behavior implies that the relaxation is thermally activated [15]. The reciprocal of the absolute temperature dependence of the relaxation time is exhibited in Fig. 10, which shows the Arrhenius formula [40]

where τ 0 is the pre-exponential factor. The values of activation energy E τ are listed in Table 1. The activation energy E σ, obtained from the dc conductivity processes, known as the activation energy for long range charge transport, and E τ from the relaxation processes, which corresponds to the short distance transport, are found to be nearly same. The comparable values of E σ and E τ (Table 1) suggest that the conduction process and the conductivity relaxation processes are both activated by the same mechanisms [37].

The electric modulus can also be defined as a Fourier transform of a relaxation function ϕ(t) such as [39]

where M ∞ is the inverse of high-frequency dielectric constant ε ∞. The function ϕ(t) gives the time evolution of the electric field within the materials. The modulus plot can be described by the Kohlrausch–Williams–Watts (KWW) function [41, 42]

where β is the stretched exponent (0 < β < 1). For an ideal Debye-type relaxation, β = 1. The smaller is the value of β means, the greater is the deviation from the Debye-type relaxation. We have fitted the experimental data in Fig. 9 to obtain the values of β. It means that the value of β can be evaluated by using the width at half height of the M″ plot (β = 1.14/FWHM). The (FWHM) was found to be almost constant with variation in temperature. The β values obtained from the present glass and its glass-ceramic nanocomposites are listed in Table 1. From this table, the values of β do not differ considerably with the variations of grain size of the present glass-ceramic nanocomposites and are fairly low, suggesting a greater departure from Debye relaxation and having a wider distribution of relaxation times. This low value of β also implies cooperative motion of the ions in the material, i.e., the jump of a mobile ion cannot be treated as an isolated event. The jump of the ion from one equilibrium site to other site causes a time-dependent movement of other ions in the surroundings, which leads to additional relaxation of the applied field [43]. On the other hand, a lower value of β indicates to higher ionic conductivity [29].

To obtain better understanding into the relaxation dynamics, we have used the scaling behavior of the modulus spectra [44]. Figure 11 exhibits a master plot of the modulus isotherms, where the frequency axis is scaled by the relaxation frequency f max and M′ (or M″) is scaled by M ∞ (or M″max). The perfect overlap of all the curves on a single master curve for all the temperatures indicates that the relaxation processes are temperature independent. The scaled spectra of M′ and M″ for the present glass and its glass-ceramic nanocomposites at a fixed temperature (353 K) are also shown in Fig. 11. It can be seen that the spectra for the present glass and its glass-ceramic nanocomposites also merge on a single master curve. This means the dynamical process controlling the conductivity relaxation indicates the same mechanism at variations of grain size for these glass-ceramic nanocomposites. Finally, the text and verified electrochemical performance of Li3V2(PO4)3 glass-ceramic nanocomposites as electrodes for energy storage devices will be discussed in our new paper.

Conclusions

37.5Li2-25V2O5-37.5P2O5 mol% glass and its glass-ceramic nanocomposites consisting of Li3V2(PO4)3 NASICON-type materials were prepared, and their XRD, SEM, and dc and ac conductivities were studied over a wide frequency and temperature range. The lattice structure of the nanoparticles can be indexed to the monoclinic unit cell of Li3V2(PO4)3 NASICON type (with the space group of P21/n), and the crystalline lattice is not distorted with variations of grain size in the resulting Li3V2(PO4)3 crystallite. As the conductivity increases, the corresponding activation energy decreases. The value of frequency exponent s decreases with the increase of temperature, implying that there is a weaker correlation effect among the Li+ ions. The scaling of the conductivity spectra along with the modulus spectra indicates that the relaxation dynamics of charge carriers follow a common mechanism for all temperatures and all differences of grain size. On the other hand, the activation energies calculated from the complex impedance plots match fairly well with the activation energies calculated from the relaxation processes. The low values of the non-exponential parameter, β, obtained from the fit of the (KWW) function to the modulus spectra, indicate a wide distribution of relaxation times and cooperative motion of the ions in the present glass and its glass-ceramic nanocomposites. The most probable conductivity relaxation time τ m decreased with decreasing of the grain size. The calculated relaxation time at 353 K for the present glass was 10.47 μs, while in its glass-ceramic nanocomposites, it was in the range of 1.84–5.41 μs. Finally, these nanocomposites are very important to use as cathode materials in Li-ion batteries because of shortened diffusion paths for Li+ ions/electrons.

References

Chowdhuri BVR, Mok KF, Xie JM, Gopalakrisnan R (1995) Solid State Ionics 76:189

Winter R, Siegmund K, Heitijans P (1997) J Non-Cryst Solids 212:215

Zhang L, Wang XL, Xiang JY, Zhou Y, Shi SJ, Tu JP (2010) J Power Sources 195:5057

Ren MM, Zhou Z, Gao XP, Peng WX, Wei JP (2008) J Phys Chem C 112:5689

Ivanishchev AV, Churikov AV, Ivanishcheva IA, Ushakov AV (2016) Ionics 22:483

Lai K, Kong A, Yang F, Chen B, Ding H, Shan Y, Huang S (2006) Inorg Chim Acta 359:1050

Muster J, Kim GT, Park JG, Park YW, Roth S, Burghard M (2000) Adv Mater 12:420

Mai L, Li S, Dong Y, Zhao Y, Luo Y, Xu H (2013) Nanoscale 5:4864

Al-Assiri MS, El-Desoky MM, Alyamani A, Al-Hajry A, Al-Mogeeth A, Bahgat AA (2010) Philos Mag 25:3421

Muthupari S, LakshmiRaghavan S, Rao KJ (1996) J Phys Chem 100:4243

Jayasinghe GDLK, Dissanayake MAKL, Bandaranayake PWSK, Souquet JL, Foscallo D (1999) Solid State Ionics 121:19

Jayasinghe GDIK, Dissanayake MAKL, Careem MA, Souquet JL (1997) Solid State Ionics 93:291

Bazan JC, Duffy JA, Ingram MD, Mallace MR (1996) Solid State Ionics 86–88:497

Ungureanu MC, Levy M, Souquet JL (1998) Ionics 4:200

Karmakar A, Ghosh A (2011) J Appl Phys 110:34101

El-Desoky MM, Hassaan MY (2002) Phys Chem Glasses 43:1

El-Desoky MM, Ragab HS (2005) Phys Stat Sol 202:1088

Dominko R, Goupil JM, Bele M, Gaberscek M, Remskar M, Hanzel D, Jamnik J (2005) J Electrochem Soc 152:A858

Gaberscek M, Dominko R, Jamnik J (2007) Electrochem Commun 9:2778

Ou Q-Z, Tang Y, Zhong Y-J, Guo X-D, Zhong B-H, Liu H, Chen M-Z (2014) Electrochim Acta 137:489

Kope M, Yamada A, Kobayashi G, Nishimura S, Kanno R, Mauger A, Gendron F, Julien CM (2009) J Power Sources 189:1154

Nguyen VH, Wang WL, Gu HB (2015) Ceramics International 41:5403

Su LM, Grote N, Schmitt F (1984) Electron Lett 20:717

Mote VD, Purushotham Y, Dole BN (2012) J Theoretical and Applied Physics 6:6

Al-Syadi AM, Al-Assiri MS, Hassan HMA, El-Desoky MM (2016) J Mater Sci: Mater Electron 27:4074

Cui L, Wang GG, Zhang HY, Suna R, Kuang XP, Han JC (2013) Ceram Int 39:3261

Brown EN, Rae PJ, Dattelbaum DM, Clausen B, Brown DW (2008) Exp Mech 48:119

Wang R, Xiao S, Li X, Wang J, Guo H, Zhong F (2013) J Alloys and Compounds 575:268

Jayswal MS, Kanchan DK, Sharma P, Pant M (2011) Solid State Ionics 186:7

Gabarczyk JE, Wasiucionek M, Machowski P, Jakubowski W (1999) Solid State Ionics 119:9

Al-Assiri MS, Mostafa MM, Ali MA, El-Desoky MM (2014) Super Lattices Micro Struct 75:127

Jonscher AK (1977) Nature 267:673

Ghosh A (1990) Phys Rev B 41:1479

Murawski L (1987) J Non-Cryst Solids 90:629

Almond DP, West AR (1983) Nature (London) 306:456

Dyre JC (1991) J Non-Cryst Solids 153:219

Hodge IM, Ngai KL, Moynihan CT (2005) J Non-Cryst Solids 351:104

Dutta A, Ghosh A (2007) J Chem Phys 127:144504

Macedo PB, Moynihan CT, Bose R (1972) Phys Chem Glasses 13:171

Bhattacharya S, Ghosh A (2003) Solid State Ionics 161:61

Kohlrausch R (1847) Prog Ann 123:393

Williams G, Watts DC (1970) Trans Faraday Soc 66:80

Reau JM, Rossignol S, Tanguy B, Rojo JM, Herrero P, Rojas RM, Sanz J (1994) Solid State Ionics 74:65

Ghosh A, Sural M (1999) Europhys Lett 47:688

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the Ministry of Higher Education, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, for supporting this research through a grant (PSCED-003-15) under the Promising Centre for Sensors and Electronic Devices (PCSED) at Najran University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Al-Syadi, A.M., Al-Assiri, M.S., Hassan, H.M.A. et al. Grain size effects on dynamics of Li-ions in Li3V2(PO4)3 glass-ceramic nanocomposites. Ionics 22, 2281–2290 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11581-016-1772-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11581-016-1772-4