Abstract

Analyzing the relationships between political parties and voters is one of the central topics of political science. Parties are expected either to be responsive to the demands of their voters or are presumed to have the power to influence voting decisions by structuring the political discourse and thereby competition regarding political issues. These two aspects are covered in the literature by research on the way parties present themselves and by electoral research, respectively. Focusing on the latter, this state-of-the-art article reviews how recent publications have analyzed the impact of party competition (macro level) on vote choice (individual level). It does so by introducing the most prominent theories of voting and party competition, summarizing the most recent results and pointing to potential problems for international comparisons such as methodological choices and different approaches to the measurement of party positions.

Zusammenfassung

Die Analyse der Beziehungen zwischen politischen Parteien und Wählern ist eines der zentralen Themen der Politikwissenschaft. Hinsichtlich der Parteien wird davon ausgegangen, dass sie sich entweder responsiv gegenüber den Forderungen ihrer Wähler zeigen oder aber die Macht haben, deren Wahlentscheidung zu beeinflussen, indem sie den politischen Diskurs und damit den Wettbewerb um politische Themen strukturieren. Diese beiden Aspekte werden zum einen in der Parteien-, zum anderen in der Wahlforschung behandelt. Mit Blick auf Letztere wird in diesem State-of-the-Art-Artikel dargestellt, wie neuere Veröffentlichungen die Auswirkungen des Parteienwettbewerbs (Makroebene) auf die Wahlentscheidung (Individualebene) analysieren. Dies geschieht durch eine Einführung in die wichtigsten Theorien zur Wahlentscheidung und zum Parteienwettbewerb, auf deren Grundlage eine Zusammenfassung der Ergebnisse neuerer, quantitativer Studien erfolgt. Potenzielle Probleme für den internationalen Vergleich werden hierbei ebenso erörtert wie wichtige methodische Neuerungen und die verschiedenen verfügbaren Ansätze zur Messung von Parteienpositionen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The analysis of electoral behavior is undoubtedly one of the core topics of political science, since this is where citizens’ political preferences are regularly translated into the selection of political personnel. More than other forms of political participation, elections may therefore be regarded as “instruments of democracy” (Powell 2000). While the individual vote decision depends on a variety of factors, it always takes place in an electoral context that is limited in time and place. This context includes not only the electoral system and the system of government (for both see Schmitt-Beck 2019), but also the party system. Parties are expected either to be responsive to the demands of their voters, or are presumed to have the power to influence voting decisions by structuring the political discourse and thereby competition between parties as to political issues. Focusing on the latter, this state-of-the-art article reviews how recent publications have analyzed the impact on vote choice that is exerted by party competition.

Below, we define party competition as institutionally structured interactions, in which political parties strategically cooperate or battle to gain power (Franzmann 2011, p. 320). As attracting voters is crucial, we will focus on how the two most prominent theories of party competition—positional and salience theory—are related to the individual vote choice. We point out that the two major theories make quite different arguments about how parties behave and interact with each other in order to attract voters, yet for both, the interaction is based on political issues rather than on candidates or other non-thematic criteria.Footnote 1 Most recently, combinations of positional and salience theory have been successfully applied in analyzing the transforming party competition across Europe. We discuss these innovations as mixed approaches.

Regarding the individual vote decisions, we categorize the encompassing theoretical literature as highly rational theories of spatial voting, competence-based theories of issue voting, and theories pointing to the role of cleavages, in order to explain voting patterns. After introducing each of these theories, we summarize the results of the most recent studies, and point to important aspects for analyzing the effect of party competition on voters’ choice in an international perspective, including methodological choices and the measurement of party positions. We have concentrated on the theoretical arguments and empirical results of the most recent studies making international comparisons, using quantitative methods to explain individual vote choice. This might be the decision for a distinct party family (e.g., radical right parties), for an incumbent party (in contrast to an opposition party), or for a party that is closest to the voter’s own position (highly relevant for spatial voting theories).

2 Theories of Vote Choice

Scholarly studies of electoral behavior have a long and lively history, and it is not our aim to provide an encompassing overview of the literature here (but see Schmitt-Beck 2019). Rather, we focus on three of the arguably most influential theories of vote choice: spatial, issue, and cleavage voting. These grand theories have been especially important in shaping the current contours of electoral studies and are also the main point of reference for those comparative studies concerning the impact on individual vote choice that is exerted by party competition.

2.1 Spatial Voting

Spatial voting theory is important among theories of vote choice and candidate preferences (Downs 1957; Enelow and Hinich 1984; Rabinowitz and Macdonald 1989). It deals with rational choice in the sense that voters’ preferences among parties are assumed to be representable by a utility function, which suggests that voters have a preferred position in a predefined issue space. Parties express their positions on the same issue space, and it is assumed that voters have some information about these positions. In their general form, spatial voting theories can be expressed for each political issue (e.g., welfare spending, values, immigration policy, etc.), but voters’ and parties’ positions are usually expressed in terms of left and right, providing something like a super dimension (Gabel and Huber 2000) by which political positions can be measured.Footnote 2 While these assumptions are shared by all spatial voting theories, they can be further divided into proximity and directional theories, depending on what the utility function of a voter looks like. The utility of voting for a party defined by proximity theory is the following:

where \(v_{i}\) is the position of voter i on the left–right ideological scale, \(u_{i}\) is his utility, and \(p_{j}\) is the position of party j in question on the same scale. It is easy to see that the utility of each voter reaches its maximum when the positions of voter i and party j overlap, i.e., they have the same position in terms of left and right. The neutral position or the middle of the scale has no specific meaning or importance in proximity theory. If a voter is on the left of the scale, but the most proximate party is on the right, the voter will still prefer that party, irrespective of the fact that they are on different sides. In contrast, directional theory (Rabinowitz and Macdonald 1989) builds on this differentiation so that utility of the voter is defined as:

with n representing the ideological middle, or the point of neutrality between left and right. In contrast to proximity theory, directional theory uses a two-step rationale (Westholm 1997). Voters first choose a side—such as for or against an issue or left vs. right ideology—and select the party that conforms most closely. The choice of the most extreme party on the same side as the voter will generate the highest utility for the voter, but if there is no party on the same side, he or she will choose the party on the other side that is the least extreme.

While both proximity and directional theories have been tested extensively (see for example Adams et al. 2005; Blais et al. 2001; Kramer and Rattinger 1997; Pierce 1997; Westholm 1997), it is virtually impossible to compare their explanatory power. The reason for this is that in a considerable number of cases, both theories come to the same prediction about which party a voter will prefer (Tomz and Van Houweling 2008). Another potential problem for spatial voting theories is the a priori choice of the dimension on which both voters and parties are located. As electoral competition is not necessarily unidimensional, the left–right ideological continuum might not accurately describe the positions held by the majority of the electorate. Also, left and right might have very different meanings across both time and space, resulting in potential problems, particularly for international comparisons. Finally, there is the risk that voters adopt biased judgments about the positions offered by parties, seeing parties that they like as being closer to their own position rather than parties that they dislike. We will discuss these potential problems in greater detail later.

2.2 Issue Voting

In contrast to spatial theories, issue voting theories do not see voters and parties taking up predefined positions. Rather, voters have a certain idea about which issues are most important to them, e.g., seeing rising inflation as being a more pressing problem than wage inequality. After ranking issues in that way, they then decide which party might be most competent in handling these issues and cast their vote accordingly (Ansolabehere and Iyengar 1994; Petrocik 1996). Assigning competence to parties relies on the assumption that parties “own” certain issues, e.g., right-wing parties are seen to be more competent in addressing inflation, while left-wing parties enjoy greater trust when it comes to addressing wage inequality. According to issue ownership theory, parties thus have a strong incentive to emphasize issues with which they are notionally connected (e.g., Belanger and Meguid 2008; Nadeau et al. 2001; Van der Brug 2004), i.e., to increase their salience but to downplay issues owned by competing parties. As with spatial theories, issue voting theories inhibit statements on how political parties should behave in order to address voters.Footnote 3

Also relevant for issue voting theories is the distinction between positional and valence issues. Issue ownership theory (Petrocik 1996) was initially developed and tested for valence issues, i.e., those on which all voters and parties share the same goal, such as reducing unemployment or fighting crime. Depending on the salience of unemployment and crime, voters will then support the party they see as most competent in handling the problem. However, not all issues are valence issues, and more recent research acknowledges positional issues on which both voters and parties can disagree (e.g., Belanger and Meguid 2008; Walgrave et al. 2012). While the relationship between valence and positional issues is still a major gap in the literature, the classical view of them as contradictory (Stokes 1963, 1992) is not shared by many recent studies. Linking valence to positional issues, Pardos-Prado (2012) argues that voters may believe that a party is best equipped to deal with a given issue because they share the parties’ position on it and further differentiate between issue goals (which can be consensual) and means to reach the goals (which can be positional).

Issue voting theories have been developed in response to the low explanatory power of spatial theories, and argue that it is much easier for voters to decide questions of issue competence rather than calculating proximities between their own position and those of the parties (Green and Hobolt 2008). In other words, voters are expected to care much more about what parties can deliver in terms of addressing political problems than about calculating proximities. For this reason, we also discuss here performance voting theories as a sub-type of issue voting theories. Performance voting studies are based on the idea that voters reward or punish incumbents for past behavior and focus on retrospective evaluations of government economic performance as important determinants of voting behavior (see, e.g., Fiorina 1981; Miller and Shanks 1996). Central to this literature is the intuition that citizens sanction incumbents based on their evaluations of a government’s policy record, especially in the area of economics. To date, a large body of work finds evidence in support of the performance voting models, demonstrating a strong relationship between economic performance and incumbent support (Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier 2007). While these economic voting theories are surely the most prominent in the field of performance studies (see Schmitt-Beck 2019), more recent research also analyzes how they feature in other policy areas (de Vries and Giger 2014).

2.3 Cleavage Voting

We end our list of the three most important voting theories by discussing the cleavage theory of voting. Compared with both spatial and issue voting theories, this one is surely the least demanding in terms of voter rationality and informational level. Voters are not expected to calculate political distance, nor to judge governments’ performances, but are assumed to support a political party because of its traditional link to a certain social group defined by long-term social divisions, known as cleavages. Initially developed as a macro-level theory by Lipset and Rokhan (1967), who differentiated between four traditional cleavages, class and religion are now seen as by far the most important. The literature on class-based (Evans et al. 1999) and religious (Norris and Inglehart 2004; Knutsen 2004) voting can thus be seen as subtypes of cleavage voting theories, and both stress that voters tend to engage in long-term relationships with political parties (Tóka and Gosselin 2010), and thus follow a much more stable voting pattern than the other two theories predict.

However, regarding explanatory power, scholars interested in the effects of both class and religion often report that the ability of these variables to explain voter choice is declining (Dalton 2002; Dogan 1995; Franklin et al. 1992). It is argued that long-term changes in the electorate, such as changing labor markets, deindustrialization, or secularization, have eroded group cohesion formed around class or denomination, thereby reducing their relevance for electoral behavior. However, other studies demonstrate relatively stable associations between class (Evans et al. 1999), religion (Elff 2007), and vote choice. Furthermore, it has been suggested that the prevalence of cleavages depends heavily on the strategies adopted by political parties, which can choose to stick to their traditional electorates or downplay cleavages in order to attract wider electoral groups via a “catch-all” strategy (Achterberg 2006; Evans and Tilley 2012). It is therefore important to note from a theoretical perspective that cleavage theory—as with spatial and issue voting theories—makes strong initial assumptions about the weight that individual voters place on party behavior.

3 Theories of Party Competition

As indicated in the previous section, each of the three dominant theories of vote choice already makes assumptions about how political parties should act in order to address voters’ concerns. Thus, parties are seen as crucial to theories of vote choice, as they define the supply side of electoral competition required to address the demands of voters. In doing so, they have to take into account the behavior of rival parties. Theoretically, there are two perspectives, namely positional and salience, which determine how competition between parties might affect the individual voter’s decision. Importantly, both are not only distinct theories of vote choice but also distinct approaches as to how party competition should operate and be measured. Also, these theories of party competition are connected, and more recent studies have made several attempts to unify them. For the moment, we introduce positional and salience theories as distinct theoretical approaches.

3.1 Positional Theory

The idea of the positional theory of party competition is that the policy platform of any party can be described by its particular position in a predefined political space. Parties take distinct positions within this space. Budge (2001) has characterized positional theory as a “confrontational theory of party competition,” since parties are assumed to always talk confrontationally on the same issues. In the original version by Downs (1957), the political space was defined by economic concerns of a free market vs. a state-oriented economy. Parties can freely take up any position in this space, but as purely and highly rational vote-seekers, they have a strong incentive to adapt their position to the given voter distribution. This is a consequence of the general assumption of parties as vote-seekers: “parties formulate policies in order to win elections, rather than win elections to formulate policies” (Downs 1957, p. 28).Footnote 4

According to positional theory, in a two-party system, rational parties have a strong incentive to locate themselves close to the median voter, dividing the electorate into two spheres. Competition between parties is then centripetal and restricted to the middle space (Pappi 2000). The optimal position of parties is far less straightforward in multi-party systems, as they also have to compete with more extremist parties. Competition among them might then be centripetal or centrifugal, i.e., taking place at the extremes of the left–right dimension (Sartori 1976). In any case, the positioning of parties relative to each other determines the votes that they can attract (Pappi 2000).

Positional theory is clearly related to spatial voting theory. In fact, both refer to the initial study of Downs’s Economic Theory of Democracy (1957), in which the behavior of voters and parties is described in spatial terms. Both theories rely on the assumption of a very high level of information: parties have to know where voters are located, and voters have to know which positions parties are taking. Furthermore, voters should be able to discriminate between the positions of parties in order to calculate and compare distances between their own position and those of all competing parties—regardless of whether they apply a proximity or directional calculation. Nevertheless, Downs himself had already discussed the role of uncertainty in party competition that might lead to “irrational” election results and governmental decision-making (Downs 1957, pp. 77–95).Footnote 5 The most pressing critique of positional theories focuses on these assumptions and points to two problems with which voters might be faced when comparing parties in spatial terms. Both points of criticism are related to the supply side of electoral competition as provided by parties, and thus directly concern our definition of party competition.

The first concern is related to the distribution of parties on the left–right scale. In some cases, these positions might be clearly separable for voters, e.g., when a communist is facing a conservative party in a two-party system. Such separations are arguably much more difficult in other multi-party settings with many rival parties, and demand a very high degree of political information; think, for example, of the Dutch and Israeli systems with more than ten relevant parties. The proxy usually employed for these supply-side characteristics is party-system polarization, understood as a measure of the spread of parties along the left–right ideological continuum (Dalton 2008). For Sartori (1976), party-system polarization is a measure of ideological differentiation. As this polarization is the central variable for positional theory, we have applied the most commonly used formula, which is basically a variance formula, following Taylor and Herman (1971):

Here, the polarization measure for a party system with N number of parties is defined by the weight attached to party i given by its relative vote share at the time of the election observed, π, the left–right weighted mean of the parties’ placement on the left–right scale Xe̅, and the left–right position of the party on the same scale, \(X_{i}\). Previous research shows that in countries with more polarized party systems, spatial voting theories are a better description of the voter’s preferences (van der Eijk et al. 2005; Lachat 2008; Pardos-Prado and Dinas 2010; Dalton 2008), because highly polarized systems make it easier for the individual voter to identify differences between the parties. However, many empirical studies regarding polarization lack conceptual clearance. Combining a variance-based polarization measurement with Sartori’s proposal of simply taking the range between the two extremes of the relevant parties seems to reveal results of higher validity in empirical studies (Schmitt and Franzmann 2018).

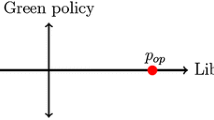

The second concern with regard to positional theory is that the political offerings as indicated by the party system polarization formula might not be one dimensional. Thus, while voters might be able to compare parties on a one-dimensional scale in terms of left and right, it is much harder, if not impossible, for them to assess parties with two, three, or even more dimensions. Recent comparative party research indeed shows that most countries can best be described by a multi-dimensional political space, including, e.g., an economic dimension and a cultural dimension of competition (Enyedi and Deegan-Krause 2010; Kitschelt 1994; Kriesi 2010). This is of limited relevance as long as these single dimensions are parallel, i.e., the position of a party in one dimension closely resembles its position in the other. However, if the distinct dimensions are orthogonal to each other, i.e., parties take very different positions in them, voters might be unable to summarize the positions into only one super dimension by which they can compare parties. The number of relevant dimensions is thus crucial for spatial theories to work; more dimensions mean a potential loss in explanatory power.

3.2 Salience Theory

The second major theory of party competition is salience theory, as originally defined by Robertson (1976). The theory relies on parties selecting one issue for emphasis and can be seen as a direct response to positional theory. One of the oldest criticisms of the Downsian approach was its neglect of non-confrontational issues, i.e., issues where almost the whole electorate is in agreement, such as fighting unemployment. Stokes (1963) has labeled these “valence issues,” and salience theory argues that parties do not compete on them in spatial terms, but rather selectively emphasize such issues as their “own,” i.e., the ones they are seen as most competent in addressing. Taking inflation as an example, right-wing parties are usually seen as more competent in addressing rising prices and therefore tend to emphasize this issue much more than left-wing parties, who themselves might highlight questions of social inequality and refuse to speak about inflation—and vice versa. In this way, parties signal to voters engaging in issue voting which issues are most important in an election, and have a strong incentive to emphasize issues that they own but to ignore those owned by other parties (Budge and Farlie 1978; Budge 2015).

Salience theory does not engage in locating parties (or voters) in a spatial way, but is interested in measuring the degree to which a party emphasizes a specific issue relative to others, i.e., how salient this issue is for the party. In orthodox salience theory, issue salience is not related to an ideological direction. Distinguishing between distinct issues is at the core of salience theory, an approach standing in sharp contrast to the tendency of summarizing all issues into one single dimension, as followed by positional theory. Separating electoral competition into distinct issues, salience theory also seems more compatible with cleavage voting theories, which rely on the assumption of several underlying political conflicts rather than on the one-dimensionality of electoral competition. However, compared with positional theory, salience theory appears as the less self-contained approach because parties cannot be entirely free to emphasize certain issues, but rather have to react to the wider socioeconomic context. For example, it will be difficult for a left-wing party to ignore the issue of rising prices when inflation is at a historic high. In such a context, voters will expect left-wing parties to say something about inflation, even if this means that they emphasize an issue that is traditionally owned by right-wing parties. In contrast to spatial positioning, emphasizing issues depends much more on contextual effects outside the electoral arena.

4 Measuring Party Competition in Comparative Studies

There is no uncontested gold standard on how to measure parties’ policies and the emphasis they chose to place on given issues. Each of the dominant methods—expert surveys, mass surveys, manifestos, computer-assisted text analysis, and media data—certainly has its own advantages and disadvantages, which have been discussed in great detail in the comparative party literature (Benoit and Laver 2007; Budge and Pennings 2007). In the following, we summarize the most important findings of these debates, especially pointing to problems arising for international comparisons. We illustrate these problems by focusing on the left-right dichotomy, which is the standard approach in the literature when it comes to measuring parties’ policy positions.

Expert surveys have been one of the commonest datasets applied to party positions since the 1980s because they are relatively cheap. Another major advantage of all expert surveys is the use of standardized and often very detailed questionnaires monitored by a country’s scientists. As country experts, they usually bring to light such things as coalition signals, political rhetoric, etc., which are seldom captured by other methods. At the same time, however, several problems arise from the question of how neutral and objective such experts are, as even scientists may have some sympathy or antipathy for particular political parties which will influence their judgments. Consequently, the expert survey carried out by Laver and Hunt (1992), and its successor by Benoit and Laver (2006), include a sympathy score of each coder for each party, enabling a correction of their judgments. In general, expert surveys also suffer from not providing an extensive time series. Further, if it is not the same coder who gathers the information, this could affect reliability. Fortunately for scholars who are interested in European politics, the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES) started in 1999 has become the most widely used dataset. Its quality regarding validity and reliability is permanently controlled, and it has been updated every four years since 2002. Beginning with 19 countries in 1999, in 2014, CHES provided data for all EU member states plus Turkey, Switzerland, and Norway. As with the datasets of Laver and Hunt and Benoit and Laver, multiple policy dimensions are covered. In addition, not only positions but also saliences of policy domains are estimated.

Another very common source for estimating party positions are mass surveys, for which respondents are asked to indicate their own position and those of the major parties on a predefined scale, usually in terms of left and right. The answers are then summarized in the form of a national mean. While such items can easily be included in surveys, this approach is also not without its problems. Most importantly, individuals might not share a common understanding of the underlying scale, some, for example, having economic or other cultural leanings when indicating a right- or left-wing position. Further, country peculiarities might make it difficult to compare left–right scores between countries and over time—a problem that is also relevant for expert surveys. Finally, mass surveys often lack salience measurements. Nevertheless, surveys on general elections often at least ask about the most important problems and comprise extensive batteries of issues.

Perhaps the most important data source for longitudinal cross-country analysis is the Manifesto Research Group on Political Representation (MARPOR; formerly the Comparative Manifesto Project, CMP). It follows a strict salience-based approach, coding so-called quasi-sentences. A quasi-sentence is the smallest unit of issue emphasis (Budge 2001). Each quasi-sentence is allocated to one of 57 predefined categories belonging to seven main policy dimensions. The data expose what percentage of a manifesto is devoted to an issue represented by one of the 57 categories (including one residual category). Thus, these salience scores vary from 0 to 100%. The main advantage of the MARPOR data is their continuous re-codability, combined with wide coverage in time and space. There is no other dataset going back to 1945 in almost all Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. One of the major disadvantages of MARPOR is that only predefined categories are covered. The more new issues arise, the less suitable the codebook becomes for covering current policies. While the MARPOR data come in the form of issue saliences, there are several ways to generate left-right party positions from them (e.g., Lowe et al. 2011). The most straightforward is to define some categories as left or right and then add up their percentages. This is exactly what the long-established RILE (right–left) scale does. Here, classifying issue categories as right or left is derived from Marxist theory, partly inductively and partly deductively (Budge and Pennings 2007).

MARPOR relies on classical hand coding, but Wordscores (Laver et al. 2003) and WordfishFootnote 6 (Slapin and Proksch 2008) apply algorithms to judge party positions via computer coding. Wordscores work as a variant of correspondence analysis (Lowe 2008), which is a novel approach to extracting dimensional information from political texts using computerized content analysis, allocating party statements within a dictionary-based space in comparison to a reference text. Thus, the reliability and validity of this approach crucially depends on the chosen reference. Wordfish does not need such a reference text or a dictionary. It relies on a statistical model of word counts. Frequencies are used to place documents on a single dimension. Hence, the reliability and validity of this approach relies on which texts are considered. Data quality is higher when the results are stable despite changes in the text corpus. No wide-ranging inter-country comparable dataset exists for either approach.

Another method for determining left–right positions is the analysis of media content. Notably, inter-country comparisons were conducted by Kriesi et al. (2006). In order to analyze the changing political scene in Europe from the 1970s onwards, the analysis of the first paragraph of relevant newspaper articles was examined, coding sentence by sentence. The aim was to detect relationships between those involved in politics and political issues (Kriesi et al. 2006, p. 931). The main disadvantage of this approach (as well as of MARPOR) is its resource-intensive coding process. Data are available for only limited points in time and for six countries.

While each of the described methods leads to specific problems when applied to cross-national and longitudinal comparisons, one circumstance that all approaches have to take into account is that party competition always takes place within a national context. This means that parties’ positioning as well as the emphasis that they place on a single issue ask for a place- and time-specific interpretation. Especially the umbrella terms of “left” and “right” can cover different issues in different countries. Left can be defined as seeking to change the status quo towards greater equality, right towards greater inequality or keeping the current state of inequality (Inglehart 1984). The same issue can therefore have different left–right meanings in two countries, thus making comparisons difficult. For instance, introducing a very low minimum wage within a laissez-faire economy might be seen to be a classical left position, while introducing the same policy within a coordinated economy might be considered a right position. Such problems of measurement pertain to each of the methods presented here, and not all approaches allow country- and time-specific meanings of left and right to be disentangled. The most sophisticated approaches are available for the MARPOR data, whereas the standard RILE approach is widely criticized for not considering the country- and time-specific meaning of left and right (Benoit and Laver 2007). Methods that consider context-specific information reveal much better results than the standard RILE approach (Gabel and Huber 2000; Franzmann 2015). Context sensitivity can be fulfilled by the country- and time-specific determination of the left–right character of each category (Franzmann and Kaiser 2006), by multi-dimensional scaling (Jahn 2011), bridge observations and Bayesian factor analysis (Koenig et al. 2013), or Bayesian latent trait models (Elff 2013). Therefore, because they offer the widest range across time and space, MARPOR data are still the main authoritative sources to judge party policies when making international comparisons.

5 Methodological State-of-the-Art

As our summary of articles in the next section will show, recent comparative studies predominately rely on multilevel models when analyzing the effects of party competition on the individual vote choice. This use of sophisticated statistical tools portrays a general trend in electoral research (see Schmitt-Beck 2019), acknowledging the fact that individual vote choice is entwined in countries, elections, and time. Indeed, nearly all the studies that we summarize make use of multilevel models, an approach that is eased by the availability of international comparative survey data, as well as by the establishment of international expert surveys for measuring party positions.

Multilevel models (see Schmidt-Catran et al. 2019) may focus on the effects of contextual variables on the individual dependent variable beyond individual characteristics (random intercept), or may analyze whether the contextual variables affect associations between individual-level variables (random slope models). Both approaches are frequently used in research on party competition and vote choice, and random intercept models are widely applied, especially when modeling the effect of issue saliences. Besides that, many studies use random slope models to examine cross-level interaction effects in order to test whether the variables of party competition moderate the effects of individual-level variables on the dependent variable, ranging from proximity (spatial theory) to issue preferences and competence perceptions (issue voting), to social group status (cleavage theory). While there is thus a great deal of variation in the independent variables (as well as possible interactions between them), the dependent variable in voting studies also shows a great deal of variation, ranging from party families, incumbent parties, closest parties in terms of proximity or directional theory, etc. In sum, this makes the comparison of results between studies quite demanding.

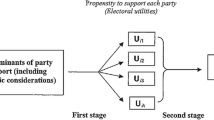

Regarding data structure, the most common way is to see individual voters nested in elections, which then vary in terms of party competition. However, some studies also see party choices nested in voters, and the latter in turn nested in elections, as voters are expected to compare the utility to be gained from each party by comparing several utility functions. Here, the use of so-called propensity-to-vote questions (PTVs) establishes itself as an alternative to categorical dependent variables—but this approach is still limited, as most international comparative surveys do not include these variables.

6 Recent Findings on the Effects of Party Competition on Vote Choice

The following review is based on the findings of the most recent studies on the effect(s) of party competition on voter choice published in leading academic journals between 2010 and 2017.Footnote 7 Our focus is on studies applying an international comparative perspective and using quantitative methods to explain individual choices. We therefore excluded the thematically closely related literature on voter–party representation, in which aggregated voters’ positions are the independent variable in order to explain parties’ positional reactions. We also excluded studies solely interested in electoral turnout (but see Schmitt-Beck 2019), and here focus exclusively on the choice that voters make between political parties. Our search resulted in 26 articles fulfilling the criteria. In order to structure our summary, we start by separating the studies according to the dominant theory of party competition that they apply, beginning with positional theory (studies listed in Table 1). We then discuss this theory’s effects on the different voting theories before we do the same with salience theory (studies listed in Table 2). Finally, we take a look at studies interested in the interplay of positional and salience theory arguments (“mixed approaches,” see Table 3). For reasons of space, we were unable to summarize each of the studies listed in the tables also in the text. We have therefore limited ourselves to those studies that best illustrate the current state of research on the three party-competition approaches. These studies are quoted in italics both in the tables and in the text.

6.1 Positional Theory and Vote Choice

Starting with positional theory in the tradition of Downs, we find studies applying this theory of party competition to each of the three major voting theories. Unsurprisingly, most of these studies are interested in the effects of party system polarization on spatial voting. The study by Pardos-Prado (2015) represents one of the most sophisticated approaches by analyzing the vote decision for a (niche) radical right party compared with an (established) mainstream right party. The author first calculates voter–party proximities on the issue of immigration, which is seen as the most relevant to the support of radical right parties. He then argues that mainstream right parties in some countries have been able to draw support from anti-immigrant voters, while in others these voters have supported the radical right, and points to the relevance of the dimensionality of party system competition for this pattern. Pardos-Prado argues that mainstream parties have been more successful in addressing anti-immigrant concerns when the national issue space is one-dimensional, i.e., when immigration concerns are very closely correlated with existing economic and cultural dimensions of party competition. Using three-level models of vote choice (party-specific choices are nested within individuals, who are nested within elections), covering 40 elections in 18 countries, and expert surveys to locate parties’ positions on the distinct dimensions, the author models cross-level interaction effects between the strength of correlation of party positions on three dimensions and immigration-proximity vote. These models show that mainstream right parties can compete more successfully with radical right parties when immigration can be assimilated into existing patterns of competition.

Other studies applying positional theory are more interested in its relevance for the predictive power of spatial voting theories or their proximity and directional subtypes. Addressing spatial theories demanding assumptions about voters’ ability to calculate distances between their own position and those of parties, Singh (2010) argues that this ability is determined by both party system polarization and the number of issue dimensions: voters tend to follow a proximity voting logic more when the party system is polarized, i.e., when the positions of parties are clearly separable (see also Pardos-Prado and Dinas 2010; Lachat 2008). However, high party system polarization loses this effect if the number of political dimensions increases, i.e., when parties hold different positions on distinct dimensions of competition. Singh shows that issue dimensionality shows very high variation across countries, the UK being the closest example of a one-dimensional space, but countries such as Spain and New Zealand following a multi-dimensional logic of party competition. Calculating multilevel models for 34 countries between 1996 and 2006, and using mass survey as well as expert survey data to identify party positions, he shows that if the complexity of an election increases, it becomes more difficult for voters to decide between parties and, ultimately, to follow a proximity logic (see also Wessels and Schmitt 2008). This joint effect of the number of parties, their polarization, and the number of dimensions is highly relevant: “all else [being] equal, the odds of a person living in New Zealand in 2002, in which political variation was not unidimensional, voting proximately are only 50% of those of an individual residing in Australia in 2004, in which politics conformed well to a single dimension” (Singh 2010, p. 433).

Also pointing to the role of party system polarization, Fazekas and Méder (2013) examine whether this contextual variable impacts on spatial voting in general, and they look at the relative explanatory power of proximity compared with directional theory. The authors start from the same assumption as Pardos-Prado (2015), namely that voters will find it easier to distinguish between the positions of parties in more polarized systems, increasing the general explanatory power of spatial theories. However, increased polarization should also lead to an increase in the explanatory power of directional compared with proximity theories, but only for those cases that really allow for a discriminatory distinction of the rival theories—this being about 25% in their sample of 27 countries. The reason for this, so the authors argue, lies in the polarization formula (see above), as this takes not only party positions into account but also parties’ voting share. If more important parties—usually located in the middle of the left–right scale—become more extreme, this sharply increases polarization, leading to very clear choices for voters who follow a directional calculation. At the same time, the distance between the central median voter and each of the major parties is increased in such a scenario, thus making proximity theory less predictive. The authors hence test for the explanatory power of increased centripetal party competition, which they assume to drive party system polarization more than increased centrifugal competition does. Their multilevel models confirm these theoretical expectations, i.e., increased party polarization leads to an increase in the number of voters engaged in spatial voting from 20% (least polarized) to 60% (most polarized context). While polarization also increases the explanatory power of directional theory—for those cases that are comparable—directional voting never outperforms proximity theory, even in highly polarized party systems.

The studies by Gómez-Reino and Llamazares (2013) and Hernández and Kriesi (2016) apply a positional logic to issue voting theories. Both studies are interested in the vote choice for niche parties as being issue entrepreneurs, that is parties that try to introduce a certain issue in order to divide established parties and their voters over it. Comparing the vote decision for a radical right party in eleven European countries, Gómez-Reino and Llamazares point to the influence of Euroscepticism on this decision. They argue that the radical right, alongside its pronounced anti-immigrant platform, tries to activate Eurosceptic attitudes in order to increase its electoral support. The authors argue that radical right parties are more successful in activating Euroscepticism the more they deviate from the mean party position on European integration. This assumption is tested and supported with mass and expert survey data on parties’ policy positions using a series of separate OLS and logit models comparing countries. Hernández and Kriesi (2016) also see that niche parties are more successful in European parliamentary elections the more they diverge from the mean of the national party system regarding European integration. The effect of this positioning is, however, subordinated to the domestic left–right dimension, as Eurosceptic voters do not support an anti-EU party that ignores their domestic preferences.

Finally, arguments derived from positional theory of party competition have also been applied to cleavage voting. Investigating the effects of party system polarization in the UK, the studies of Evans and Tilley (2012) and Milazzo et al. (2012) report that the electoral information offered by Labour and the Conservatives is highly correlated with the level of class voting over time. Their findings—based on multilevel (Evans and Tilley 2012) and structural equation models (Milazzo et al. 2012)—suggest that the less polarized the parties’ positions are on the class dimension, the less we can expect voters’ positions on the class dimension to determine their vote (see also Achterberg 2006; Elff 2007; Spies 2013 for similar findings in a cross-national perspective). Both studies operationalize party system polarization on a left–right dimension, arguing that this is the dominant dimension in the UK party system, highly related to class conflict. While the decline of class-based voting has usually been considered a consequence of changes on the demand side of electoral competition (less unionization, increased individualization, less demand for redistributive policies, etc.), both studies come to the conclusion that the electoral strategies of the two major parties are equally relevant to the decline in class-based voting. Milazzo et al. identify two reasons for this. First, when the distance between Labour and the Conservatives declines, citizens are less likely to perceive class differences between the parties, which they see as a necessary condition for class status to impact voter choice. Secondly, party elites have, in general, fewer incentives to campaign on issues that do not distinguish the party from its opponent(s), since such dimensions may be of little relevance even to those voters who still perceive party differences.

6.2 Salience Theory and Vote Choice

We now turn to studies analyzing the impact of salience theory in a cross-national perspective. We were not able to find any study exclusively applying salience arguments to spatial voting. This is hardly surprising, as spatial voting theories are closely related to positional theory in the tradition of Downs and therefore measure party statements in positions rather than issue saliences. In contrast, salience theory is closely related to issue ownership theories, and we found several studies following this tradition. One of the clearest examples is the study by Williams (2015), who analyzes defense issue voting from a cross-national perspective. Defense spending is not usually considered an area that is relevant to vote choice outside the US. However, relying on survey data from 26 countries between 1985 and 2006, Williams is able to show that the more parties emphasize defense spending in their manifestos, the more voters base their choice on that issue. The rationale behind this is that parties’ first reaction to international crises is to emphasize the need to increase defense spending. Aware of the international problems, voters listen to these statements and choose the party most competent to handle them.

The study by Burschner et al. (2015) analyzes the vote choice for a radical right party in eleven Western European countries, and points to the role of the salience of immigration and crime in national news media. It is argued on the basis of issue ownership theory that anti-immigrant parties own both issues, link them, and closely focus their electoral campaigns on them. Voters are therefore seen to react to increased issue salience in the core domain of the radical right when national media also support the view that immigration and crime are important problems that need to be addressed. Using elaborate and time-intensive hand coding of more than 20,000 news stories in the countries being analyzed, matching these with survey data from 2009, and applying rare-events logistic regressions, the authors conclude that the salience of crime and immigration sharply increases the likelihood of voters choosing a radical right party. This effect is stronger for voters who already show some sympathy for such parties.

That purely salience-motivated arguments can also be applied to cleavage theories is shown by Jansen et al. (2012). The authors analyze the influence of religion on voter choice in the Netherlands from 1971 to 2006. As with class, religious denomination and religiosity are usually seen as a cleavage of declining importance for individual voters. Demand-side factors such as secularization and individualization are considered to be the main drivers here. However, the authors argue that party policy also plays an important role in the decline of the influence of religion. Applying this top-down perspective to the Netherlands, and borrowing their theoretical argument from the class voting literature, Jansen et al. make the point that parties have to activate voters’ religious orientations by emphasizing the salience of religiosity in politics. In particular, this can be done by stressing issues of traditional morality in manifestos (MARPOR data), which the authors then find to be strongly correlated with vote choice and denomination. This effect of issue salience is also much stronger for churchgoers than for other voters, leading the authors to conclude that religious parties face a tradeoff between binding their traditional supporters to them and maximizing vote share by de-emphasizing traditional moral values. This tradeoff resembles that faced by social democratic parties in terms of class, but the important point here is that parties can decide between the two options and adapt their electoral strategies accordingly.

6.3 Mixed Approaches and Vote Choice

We have introduced positional and salience theory as distinct and partly contradictory theoretical perspectives on party competition. While this is reasonable because of their distinct assumptions about parties’ behavior, issue dimensionality, and of the level of information on the side of both parties and voters, there have been several attempts in the literature during the last decade to unify the approaches. These studies focus on the interplay of party system polarization and issue salience, arguing, e.g., that in order to be regarded as a salient issue by voters, parties should provide voters with clearly distinguishable positions on a given issue. Rational voters would otherwise have little reason to cast their vote in a dimension in which parties do not show any difference, and rational parties would show little interest in emphasizing issues which do not distinguish them from rival parties. Most recently, the interplay of positional and salience theory has also been used to analyze the rise of so-called niche parties (Meguid 2008; Wagner 2012; Zons 2016) or “challenger” (De Vries and Hobolt 2012), e.g., radical right or radical left parties. Also, the concept of “issue yield” (De Sio and Franklin 2012) contributes to the further development of modeling party behavior beyond clear predefined issue dimensions.

Analyzing the vote choice for challenger parties, De Vries and Hobolt (2012) argue that these new competitors have a strong incentive to manipulate existing patterns of party competition by introducing a new issue dimension, i.e., by increasing its salience. Differentiating parties between mainstream government, mainstream opposition, and challenger parties, the authors argue that in particular the latter will try to engage in this strategy, as they are the losers in the existing dimension(s) of competition. Faced with the objective of increasing issue salience, challenger parties then adopt a highly extreme position in the issue dimension that they want to establish, which is assumed to be a more successful strategy when the other parties adopt centrist positions. As established parties will react to the new competitor—some will move from the middle towards the challenger’s position and some away from it—they heighten the public awareness of party differences on new issues and thereby increase their salience. If voters care about this newly-evolving issue—along the lines of issue voting theories—both rising salience and polarization may lead to changes in mass identification on the basis of the new issue dimension, eventually leading to changing voting behavior. Combining these salience and positional arguments, De Vries and Hobolt then empirically address them for European integration as a newly emerging issue dimension. Based on multilevel multinomial models for 21 Western and Eastern European countries in 2004, they first show that Eurosceptic voters are more likely to vote for challenger parties. Using time series cross-section models with challenger parties’ voter shares as the dependent variable, they then apply expert survey data on both issue salience and the positions of parties to show that the product of both variables in the dimension of European integration is significantly correlated with better electoral results for challenger parties. These models include 14 Western European countries from 1984 to 2006, and also control for parties’ positions in the left–right dimension, thereby also addressing the question of issue-space dimensionality.

Also combining issue salience and polarization arguments, Hobolt and Spoon (2012) analyze vote switching (compared with national elections) in European Parliament elections. Based on multilevel models for 27 countries in 2009, they show that the degree of politicization of the EU in the domestic arena shapes the extent to which voters engage in EU-specific proximity voting at the European level. More specifically, their indicators of the level of politicization are the degree of party system polarization on the issue of European integration (measured by expert survey data) and the contentiousness of European integration in the campaign coverage (based on a coding of more than 50,000 television and newspaper stories in the weeks prior to the European Parliament election). Hobolt and Spoon argue that party polarization is a central determinant of the politicization of European Parliament elections, as only a polarized national party system offers voters real choices on the issue of European integration; it also increases the salience of European issues to them. While this should lead voters to cast their vote in European Parliament elections more on the EU issue, this is further amplified by the national news content—a salience theory argument. Thus, the authors expect that disagreements between voters and parties over EU issues will play a greater role in voters’ European Parliament choices when the problems associated with European integration are highlighted in the media during the campaign. Their empirical investigation supports these theoretical assumptions, but only the interplay of neutral or negative news campaigning and a high level of party system polarization shows an increase in EU proximity voting.

The study carried out by Pardos-Prado (2012) addresses the relationship between valence judgments—i.e., voters’ perceptions of party competence in dealing with salient issues—and polarization. While it is a common assumption in the literature that a high salience of valence issues should be associated with a low salience of positional issues—and therefore low levels of party system polarization—the author challenges this assumption. Based on multilevel models of 21 countries in 2004, he finds highly significant cross-level interaction effects between left–right party system polarization and issue voting based on party competence perceptions in the areas of unemployment, immigration, and environment protection, areas traditionally seen as being valence based or positional. These findings question the prevalent view of the relationship between polarization and valence issue voting, and point to the need to distinguish conceptually between valence and positional issues, rather than seeing them as simply contrasting terms. Also, the study makes a strong claim to relate positional theory to voting theories other than spatial voting.

The perhaps most remarkable theoretical innovation that bridges the divide between salience and position theory is the concept of the “issue yield” (De Sio and Franklin 2012). The central idea of issue yield is that parties modulate their issue emphases according to their issue-specific, individual risk–opportunity profile. Hence, according to this model, concentrating on issues with the highest salience in a party system is not the most promising strategy for many parties when it comes to attracting voters. Instead, parties will focus on those issues which unite their core voters and, at the same time, are widely supported by the overall electorate. Issue yield can therefore be defined “as the degree to which an issue allows a party to overcome the conflict between protection and expansion of electoral support” (De Sio and Weber 2014, p. 871). In general, the issue-yield model applies the Downsian rationale in explaining party strategies. However, it does not necessitate the existence of a predefined left–right policy space. The issue-yield concept considers valence and position issues as two poles of a continuum in which the parties can define the character of each issue. Parties are free to choose those bundles of issues that they think deliver the best risk–opportunity structure (De Sio et al. 2016, p. 485). Analytically, this model is suitable for application in analyzing party systems without stable ideological dimensions.

Applying multi-level modeling, De Sio and Franklin (2012) demonstrate how the issue-yield model is able to better explain the reasons why voters choose a specific party. Studying the European Parliament elections of 2009 and 2013, the issue-yield concept enables us to explain why the issue of European integration has been kept out of party competition by and large, while it was the most important topic among the electorate (De Sio et al. 2016). Using data from the European Election Study (EES) and the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES), the authors apply a three-level model, which sees voter–party combinations on propensities to vote nested in individuals, and these to be nested in party systems. They show that mainstream parties avoided talking about European integration since their core electorate was split on this question, tending to punish the party elite in the case of it taking any position on this issue.

7 Conclusion

Summarizing our review of the international comparative literature on party competition and vote choice, we conclude that recent studies still mainly rely on positional or salience theory when theoretically addressing the role of parties. Regarding the individual vote decisions, both highly rational theories of spatial voting, competence-based theories of issue voting, and theories pointing to the role of cleavages are applied. While positional and salience theory are distinct and partly contradictory, theoretical perspectives on party competition with distinct assumptions about parties’ behavior, issue dimensionality, and level of information on the side of both parties and voters, there have been several attempts in the literature during the past decade to unify the approaches. These studies frequently focus on the interplay between party system polarization and issue salience—a promising road for further research.

Regarding methodological issues, the literature shows a highly sophisticated level of methodological complexity when it comes to modeling voter–party relationships. However, more serious but rarely discussed potential problems arise from the objective of measuring party competition. While expert surveys and data provided by the hand coding of party manifestos are by far the most prominent approaches here, each presents its own advantages and disadvantages. While we do not want to state that one approach is superior to the other, we end our review by calling to mind that expert surveys and MARPOR data are strongly affiliated to either positional or salience theory. Therefore, they also entail distinct problems when addressing the effects of party competition on vote choice in a cross-national perspective, and especially so where different periods are concerned.

The major challenge for the contemporary study of European party competition is how to integrate the dynamic of the transforming political landscape. The “old” catch-all parties are vanishing, or are at least losing their dominant role across Europe, while populist and left-libertarian cosmopolite parties have become stronger. The traditional socioeconomic cleavages are in decline, and cultural issues dominate the agenda. However, this has not yet led to a stable ideological space as it is assumed in Downsian theory. Rather, especially in Southern Europe, parties select issues regardless of the ideological camp to which these issues belong. Parties thus freely combine issues without generating a new common ideological space. Combining both positional and salience arguments, the issue-yield concept offers a framework that enables researchers to analyze individual party calculus without making strong assumptions on the ideological space of a given party system. Hence, it is suitable to be applied in explaining patterns of dynamically changing party systems, both in single- (see, e.g., Franzmann et al. 2018) and cross-country studies. Future studies of party competition and vote choice will have to do even more in order to overcome the old divide between positional and salience theory. It is only then that those studies will be able to analyze the causal mechanisms behind the dramatic change in the European party system landscape.

Notes

This is not to say that non-issue motivations are not relevant to voters. However, as far as the party competition literature is concerned, parties address voters exclusively via political issues.

Thus, spatial theories are labeled “left–right voting” in Schmitt-Beck (2019).

Recent findings support the hypothesis that reciprocal effects between the core electorate and their preferred party lead to the establishment of issue ownerships (Neundorf and Adams 2016).

Nowadays, the literature on party behavior sees parties as simultaneous policy-, office-, and vote-seekers (Strom 1990).

A recent study of Ezrow et al. (2014) shows that voters abstain from voting for parties where they are uncertain as to their position.

A detailed description of the Wordscores approach can be found at: https://www.tcd.ie/Political_Science/wordscores/index.html. Wordfish’s project website is: http://www.wordfish.org/. Both websites also provide the program codes ready for application.

These are: American Journal of Political Science, American Political Science Review, American Journal of Sociology, American Sociological Review, Electoral Studies, Comparative Political Studies, European Journal of Political Research, European Union Politics, Journal of Politics, Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, Party Politics, and West European Politics.

References

Achterberg, Peter. 2006. Class voting in the new political culture. Economic, cultural and environmental voting in 20 western countries. International Sociology 21:237–261.

Adams, James, Samuel Merrill III, and Bernard Grofman. 2005. A unified theory of party competition: A cross-national analysis integrating spatial and behavioral factors. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Ansolabehere, Stephen, and Shanto Iyengar. 1994. Riding the wave and claiming ownership over issues: The joint effects of advertising and news coverage in campaigns. The Public Opinion Quarterly 58:335–357.

Belanger, Éric, and Bonnie M. Meguid. 2008. Issue salience, issue ownership, and issue-based vote choice. Electoral Studies 27:477–491.

Benoit, Kenneth, and Michael Laver. 2006. Party policy in modern democracies. London: Routledge.

Benoit, Kenneth, and Michael Laver. 2007. Estimating party policy positions: Comparing expert surveys and hand coded content analysis. Electoral Studies 26:90–107.

Blais, André, Nadeau, Richard, Elisabeth Gidengil, and Neil Nevitte. 2001. The formation of party preferences: Testing the proximity and directional models. European Journal of Political Research 40:81–91.

Van der Brug, Wouter. 2004. Issue ownership and party choice. Electoral Studies 23:209–233.

Budge, Ian. 2001. Theory and measurement of party policy positions. In Mapping policy preferences. Estimates for parties, electors, and governments 1945–1998, eds. Ian Budge, Hans-Dieter Klingemann, Andrea Volkens, Judith Bara, and Eric Tanenbaum, 75–92. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Budge, Ian. 2015. Issue emphases, saliency theory and issue ownership: A historical and conceptual analysis. West European Politics 38:761–777.

Budge, Ian, and Dennis Farlie. 1978. The potentiality of dimensional analyses for explaining voting and party competition. European Journal of Political Research 6:203–232.

Budge, Ian, and Paul Pennings. 2007. Missing the message and shooting the messenger: Benoit and Laver’s ‘response’. Electoral Studies 26:136–141.

Burschner, Bjorn, Joost van Spanje, and Claes H. de Vreese. 2015. Owning the issues of crime and immigration: The relation between immigration and crime news and anti-immigrant voting in 11 countries. Electoral Studies 38:59–69.

Dalton, Russell J. 2002. Political cleavages, issues, and electoral change. In Comparing democracies 2. New Challenges in the Study of Elections and Voting, eds. Lawrence LeDuc, Richard G. Niemi, and Pippa Norris, 189–209. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Dalton, Russell J. 2008. The quantity and the quality of party systems. Comparative Political Studies 41:899–920.

Dogan, Mattei. 1995. Erosion of class voting and of the religious vote in Western Europe. International Social Science Journal 47:525–538.

Downs, Anthony. 1957. An economic theory of democracy. New York: Harper and Row.

Duch, Raymond M., Jeff May, and David A. Armstrong. 2010. Coalition-directed voting in multiparty democracies. American Political Science Review 104:698–719.

Elff, Martin. 2007. Social structure and electoral behavior in comparative perspective: The decline of social cleavages in Western Europe revisited. Perspectives on Politics 5:277–294.

Elff, Martin. 2013. A dynamic state-space model of coded political texts. Political Analysis 21:217–232.

Enelow, James M., and Melvin J. Hinich. 1984. The spatial theory of voting. Cambridge; University Press.

Enyedi, Zsolt, and Kevin Deegan-Krause. 2010. Introduction: The structure of political competition in Western Europe. West European Politics 33:415–418.

Evans, Geoffrey, and James Tilley. 2012. The depoliticization of inequality and redistribution: Explaining the decline of class voting. The Journal of Politics 74:963–976.

Evans, Geoffrey, Anthony Heath, and C. Payne. 1999. Class: Labour as a catch-all party? In Critical elections: British parties and voters in long-term perspective, eds. Geoffrey Evans and Pippa Norris, 87–101. London: Sage.

Ezrow, Lawrence, Jonathan Homola, and Margit Tavits. 2014. When extremism pays: Policy positions, voter certainty, and party support in postcommunist Europe. The Journal of Politics 76:535–547.

Fazekas, Zoltán, and Zsombor Zoltán Méder. 2013. Proximity and directional theory compared: Taking discriminant positions seriously in multi-party systems. Electoral Studies 32:693707.

Fiorina, Morris. P. 1981. Retrospective voting in American national elections. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Franklin, Mark. N., Thomas T. Mackie, and Henry Valen. 1992. Electoral change: Responses to evolving social and attitudinal structures in western countries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Franzmann, Simon T. 2011. Competition, contest, and cooperation. The analytical framework of the issue-market. Journal of Theoretical Politics 23:317–343.

Franzmann, Simon T. 2015. Towards a real comparison of left-right indices: A comment on Jahn. Party Politics 21:821–828.

Franzmann, Simon, and André Kaiser. 2006. Locating political parties in policy space. A reanalysis of party manifesto data. Party Politics 12:163–188.

Franzmann, Simon T., Heiko Giebler, and Thomas Poguntke. 2018. It’s not only the economy stupid! Issue Yield at the 2017 German Federal Election. Special Issue in West European Politics 1/2019, ed. by Lorenzo De Sio, and Romain Lachat (under review).

Gabel, Matthew J., and John D. Huber. 2000. Putting parties in their place: Inferring party left-right ideological positions from party manifesto data. American Journal of Political Science 44:94–103.

Gomez, Raul, Laura Morales, and Luis Ramiro. 2016. Varieties of radicalism: Examining the diversity of radical left parties and voters in Western Europe. West European Politics 39:351–379.

Green, Jane, and Sara B. Hobolt. 2008. Owning the issue agenda: Party strategies and vote choices in British elections. Electoral Studies 27:460–476.

Gómez-Reino, Margarita, and Iván Llamazares. 2013. The populist radical right and European integration: A comparative analysis of party-voter links. West European Politics 36:789–816.

Han, Kyung Joon. 2016. Income inequality and voting for radical right-wing parties. Electoral Studies 42:54–64.

Harteveld, Eelco. 2016. Winning the ‘losers’ but losing the ‘winners’? The electoral consequences of the radical right moving to the economic left. Electoral Studies 44:225–234.

Hernández, Enrique, and Hanspeter Kriesi. 2016. Turning your back on the EU. The role of Eurosceptic parties in the 2014 European Parliament elections. Electoral Studies 44:515–524.

Hobolt, Sara B., and Jae-Jae Spoon. 2012. Motivating the European voter: Parties, issues and campaigns in European Parliament elections. European Journal of Political Research 51:701–727.

Hong, Geeyoung. 2015. Explaining vote switching to niche parties in the 2009 European Parliament elections. European Union Politics 16:514–535.

Inglehart, Ronald. 1984. The changing structure of political cleavages in western society. In Electoral change in advanced industrial democracies: Realignment or dealignment? Eds. Russell J. Dalton, Scott C. Flanagan, and Paul A. Beck, 25–69. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Jahn, Detlef. 2011. Conceptualizing left and right in comparative politics: Towards a deductive approach. Party Politics 17:745–765.

Jansen, Giedo, Nan Dirk de Graaf, and Ariana Need. 2012. Explaining the breakdown of the religion-vote relationship in The Netherlands. 1971–2006. West European Politics 35:756–783.

Kitschelt, Herbert. 1994. The transformation of European social democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Knutsen, Oddbjørn. 2004. Religious denomination and party choice in Western Europe: A comparative longitudinal study from eight countries, 1970–97. International Political Science Review 25:97–128.

Koenig, Thomas, Moritz Marbach, and Moritz Osanbrügge. 2013. Estimating party positions across countries and time—a dynamic latent variable model for manifesto data. Political Analysis 21:468–491.

Kramer, Jürgen, and Hans Rattinger. 1997. The proximity and the directional theories of issue voting: comparative results for the US and Germany. European Journal of Political Research 32:1–29.

Kriesi, Hanspeter. 2010. Restructuration of partisan politics and the emergence of a new cleavage based on values. West European Politics Volume 33:673–685.

Kriesi, Hanspeter, Edgar Grande, Romain Lachat, Martin Dolezal, Simon Bornschier, and Timotheos Frey. 2006. Globalization and the transformation of the national political space: Six European countries compared. European Journal of Political Research 45:921–956.

Lachat, Romain. 2008. The impact of party polarization on ideological voting. Electoral Studies 27:687–698.

Laver, Michael, and W. Ben Hunt. 1992. Policy and party competition. London: Routledge.

Laver, Michael, Kenneth Benoit, and John Garry. 2003. Estimating the policy positions of political actors using words as data. American Political Science Review 97:311–331.

Lewis-Beck, Michael, and Mary Stegmaier. 2007. Economic models of voting. In The Oxford handbook of political behavior, eds. Russell J. Dalton, and Hans-Dieter Klingemann, pp. 518–537, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lipset, Seymour Martin, and Stein Rokkan. Eds. 1967. Party systems and voter alignments: Cross-national perspectives. Toronto: Free Press.

Lowe, Will. 2008. Understanding wordscores. Political Analysis 16:356–371.

Lowe, Will, Kenneth Benoit, Slava Mikhailov, and Michael Laver. 2011. Scaling policy positions from coded units of political texts. Legislative Studies Quarterly 36:123–155.

Meguid, Bonnie M. 2008. Party competition between unequals: Strategies and electoral fortunes in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Milazzo, Caitlin, James Adams, and Jane Green. 2012. Are voter decision rules endogenous to parties’ policy strategies? A model with applications to elite depolarization in Post-Thatcher Britain. The Journal of Politics 74:262–276.

Miller, Warren E, and J. Merrill Shanks. 1996. The new American voter. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Nadeau, Richard, André Blais, Elisabeth Gidengil, and Neil Nevitte. 2001. Perceptions of party competence in the 1997 election. In Party politics in Canada, eds. Hugh G. Thorburn, and Alan Whitehorn, 413–430. Prentence Hill, Toronto.

Neundorf, Anja, and James Adams. 2016. The micro-foundations of party competition and issue ownership: The reciprocal effects of citizens’ issue salience and party attachments. British Journal of Political Science 48:385–406.

Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart 2004. Sacred and secular: Religion and politics worldwide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pappi, Franz Urban. 2000. Zur Theorie des Parteienwettbewerbs. [On the theory of party competition] In 50 Jahre empirische Wahlforschung in Deutschland. Entwicklung, Befunde, Perspektiven, Daten, eds. Markus Klein, Wolfgang Jagodzinski, Dieter Ohr, Ekkehard Mochmann, 85–105. Wiesbaden: Westdeutscher Verlag.

Pardos-Prado, Sergi. 2012. Valence beyond consensus: Party competence and policy dispersion from a comparative perspective. Electoral Studies 31:342–352.

Pardos-Prado, Sergi. 2015. How can mainstream parties prevent niche party success? Center-right parties and the immigration issue. The Journal of Politics 77:352–367.

Pardos-Prado, Sergi, and Elias Dinas. 2010. Systemic polarisation and spatial voting. European Journal of Political Research 49:759–786.

Petrocik, John R. 1996. Issue ownership in presidential elections, with a 1980 case study. American Journal of Political Science 40:825–850.

Pierce, Roy. 1997. The directional theory of issue voting: directional versus proximity models: Verisimilitude as the criterion. Journal of Theoretical Politics 9:61–74.

Powell, G. Bingham. 2000. Elections as instruments of democracy: Majoritarian and proportional visions. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Rabinowitz, George, and Stuart Elaine Macdonald. 1989. A directional theory of issue voting. The American Political Science Review 83:93–121.

Robertson, David. 1976. A theory of party competition. London: John Wiley & Sons.

Sartori, Giovanni. 1976. Parties and party systems: A framework for analysis. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Schmidt-Catran, Alexander W., Malcolm Fairbrother and Hans-Jürgen Andreß. 2019. Multilevel models for the analysis of comparative survey data: Common problems and some solutions. In Cross-national comparative research – analytical strategies, results and explanations. Sonderheft Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie. Eds. Hans-Jürgen Andreß, Detlef Fetchenhauer and Heiner Meulemann. Wiesbaden: Springer VS. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-019-00607-9.

Schmitt-Beck, Rüdiger. 2019. Political systems and electoral behavior: A review of internationally comparative multilevel research. In Cross-national comparative research – analytical strategies, results and explanations. Sonderheft Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie. Eds. Hans-Jürgen Andreß, Detlef Fetchenhauer and Heiner Meulemann. Wiesbaden: Springer VS. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-019-00608-8.

Schmitt, Johannes, and Simon Franzmann. 2018. Measuring ideological polarization in party systems: An evaluation of the concept and the indicators. Manuscript, Düsseldorf: Düsseldorf University.

Singh, Shane P. 2010. Contextual influences on the decision calculus: A cross-national examination of proximity voting. Electoral Studies 29:425–434.

De Sio, Lorenzo, and Mark N. Franklin. 2012. Strategic Incentives, Issue Proximity and Party Support in Europe. West European Politics 35:1363–1385.

De Sio, Lorenzo de, and Till Weber. 2014. Issue yield: A model of party strategy in multidimensional space. American Political Science Review 108:870–85.

De Sio, Lorenzo, Mark N. Franklin, and Till Weber. 2016. The risks and opportunities of Europe: How issue yield explains (non-)reactions to the financial crisis. Electoral Studies 44:483–91.

Slapin, Jonathan, and Sven-Oliver Proksch. 2008. A scaling model for estimating time series party positions from texts. American Journal of Political Science 52:705–722.

Spies, Dennis. 2013. Explaining working-class support for extreme right parties: A party competition approach. Acta Politica 48:296–325.

Stokes, Donald E. 1963. Spatial models of party competition. American Political Science Review 57:368–377.