Abstract

What is the proportionate punishment for conduct that is neither harmful nor wrongful? A likely response to that is that one ought not to be punished at all for such conduct. It is, however, common for the state to punish harmless conduct the wrongfulness of which is not always apparent. Take, for example, the requirement that those who give investment advice for compensation do so only after registering as an investment advisor. Advising a person on how to invest his or her funds and accepting a fee for the advice without registering with the government does not seem harmful or wrongful, so long as no fraud is involved, the relevant parties understand the relevant risks, and so on. But practicing investment advising without registering is a crime for which one may be convicted and punished. When one thinks of crimes, paradigmatic offenses are crimes like murder, rape, and robbery, but offenses like failure to register as an investment advisor are different. But in what way? One standard explanation is the distinction between two types of offenses, malum in se and malum prohibitum. Some offenses, like murder, are wrongs “in themselves” (“in se”) whereas other offenses, like investment advising without registering as an advisor, are wrongs because they have been prohibited (“prohibitum”). The question this Essay asks is how we should think about proportionality of punishment when punishing such mala prohibita offenses. This Essay presents a framework for such proportionality determinations and raises some challenges such a framework would need to confront.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

What is the proportionate punishment for conduct that is neither harmful nor wrongful? A likely response to that is that one ought not to be punished at all for such conduct. It is, however, common for the state to punish harmless conduct the wrongfulness of which is not always apparent. Take, for example, the requirement that those who give investment advice for compensation do so only after registering as an investment advisor.Footnote 1 Advising a person on how to invest his or her funds and accepting a fee for the advice without registering with the government does not seem harmful or wrongful, so long as no fraud is involved, the relevant parties understand the relevant risks, and so on. But practicing investment advising without registering is a crime for which one may be convicted and punished.

When one thinks of crimes, paradigmatic offenses are crimes like murder, rape, and robbery, but offenses like failure to register as an investment advisor are different. But in what way? One standard explanation is the distinction between two types of offenses, malum in se and malum prohibitum. Some offenses, like murder, are wrongs “in themselves” (“in se”) whereas other offenses, like investment advising without registering as an advisor, are wrongs because they have been prohibited (“prohibitum”). The question this Essay asks is how we should think about proportionality of punishment when punishing such mala prohibita offenses.Footnote 2 This Essay presents a framework for such proportionality determinations and raises some challenges such a framework would need to confront.

2 What are Mala Prohibita Offenses? A Typology

There are several types of crimes that are usually discussed under the heading of mala prohibita offenses.

First, there is conduct that may be, in Larry Alexander and Kimberly Ferzan’s terms, “presumptively culpable,” though not always culpable.Footnote 3 Alexander and Ferzan give as one of their examples driving in excess of the speed limit, which is not inherently risky but may be “presumptively reckless.”Footnote 4

Second, the state frequently criminalizes certain conduct not because it directly causes harm but because it might lead or contribute to harm less directly, by, say, further acts by the agent of the conduct or others. Various possession offenses—drugs, weapons, child pornography—may be categorized in this group of offenses.Footnote 5

Third, the state imposes certain affirmative duties in order to aid law enforcement. For instance, information-gathering offenses like the requirement that one declare the amount of currency one is carrying abroad over a certain minimum is a way of criminalizing conduct that seems morally neutral in order to unveil more clearly morally suspect conduct, like running an illicit business.Footnote 6 These types of offenses frequently also require reports of signs of suspicious activities by other people.Footnote 7

Fourth, closely related, the state also criminalizes conduct that in itself may be morally neutral but is easier to detect and is associated with certain types of criminal behavior. Money laundering, defined roughly as engaging in transactions with money that is derived from certain criminal activities, is an example of a crime like this.Footnote 8

Fifth, there are offenses that have been called “regulatory offenses,” sometimes called “public welfare offenses,”Footnote 9 as opposed to ordinary offenses. Regulatory offenses refer to a type of criminal offense that the government enacts as a way of enforcing its regulations of various aspects of our lives—air quality, food safety, environmental preservation, and so on. In United States law, typically, a statute would authorize a federal agency (or authorize the President to authorize an agency) to promulgate regulations to implement the statute and criminalize certain violations of the statute or the regulations.Footnote 10

Sixth, the state may enact crimes that eliminate culpable mental state requirements, even if that entails criminalizing conduct that is not culpable, as a way of preventing undesirable behavior and easing the burden of prosecuting. These crimes are often referred to as “strict liability” crimes.Footnote 11

Now that we have a typology of mala prohibita offenses, the next question to ask is how to think about proportionate punishments for violating such offenses.

3 Mala in Se and Mala Prohibita Components of Culpability

While a typology like the one given in the previous section is pretty typical, it is not always easy to classify offenses as a malum prohibitum or a malum in se. Take, for example, the crime of going over the speed limit. Is it a malum in se or a malum prohibitum offense? The malum in se component has to do with endangering others through driving in an unsafe manner. However, a sober, competent driver may drive above the speed limit on purpose with due care without imposing any unwarranted risk on others, if the speed limit is set too low or if the surrounding conditions are such that there is no additional risk of harming others by speeding. That would still be an offense because the speed limit means what it says and there is a prohibition on driving over a certain speed. In that case, speeding is a malum prohibitum offense. Speeding may not be a wrong in itself, though it may be a wrong because it is prohibited. For this reason, when thinking about the seriousness of mala prohibita offenses, it may be better to think of offenses as having mala prohibita and mala in se components as opposed to being a malum prohibitum or a malum in se offense.Footnote 12

Why is it important to separate out these two components? When an offense has two components, the malum in se component and the malum prohibitum component, the proportionality determination needs to track the two components separately because the two components implicate different types of wrongs. To see this, consider a person who drives dangerously (knowing that he is driving dangerously) and drives above the speed limit (knowing that he is driving above the speed limit). An observer might remark to the driver, “What you are doing is dangerous and is against the law.” If the malum in se component is about being dangerous to others, what is the malum prohibitum component about? It seems that the malum prohibitum component is about going against a legal directive (with a culpable mental state, say knowingly), even when not following the directive does not seem otherwise morally wrong. In other words, the wrong to be attributed to the malum prohibitum component is the wrong of disobedience.

Speeding is an offense that is “presumptively culpable,” which makes it easy to see that there are the two components. But other types of offenses can also be broken down and analyzed in the same way. So, we might say something similar about an environmental regulatory offense where dumping a certain type of harmful chemical not only goes against a legal directive, which provides the malum prohibitum dimension, but also increases the risk of people nearby getting sick, which sounds more like a malum in se. Even crimes that are ordinarily considered to be mala in se offenses often have mala prohibita components. Take the case of assisted suicide where a purposeful killing may not be morally wrong but is nevertheless criminally prohibited. In such a case, a person who kills knowing that what he or she is doing is criminal even if the conduct seems morally justified would be disobeying the state’s directive not to kill on purpose even in such situations. As these examples show, crimes that are ordinarily considered to be mala in se offenses can have mala prohibita components, and the so-called mala prohibita offenses can have mala in se components as well. Of course, it is still possible to classify offenses as “mostly malum in se” or “mostly malum prohibitum” depending on which component predominates, but when the task is to determine proportionate responses to offenses, it helps to identify the two components.

We may accordingly think about culpability of various offenses by applying the following formula:

Ct is the “Total Culpability,” Ca is culpability attributable to the badness of the prohibited act itself (for example, driving dangerously), and Cd is culpability attributable to the act of disobeying a prohibition (the portion of culpability having to do with “and is against the law”).Footnote 13

To illustrate how this framework would apply, take two drivers, both knowingly driving over the speed limit, but one of them is driving dangerously (knowing that he is driving dangerously) and the other believes that he is driving safely. The value of Ca for the one who (let’s assume reasonably) believes that he is driving safely is very low, so Ct for the person who reasonably believes that he is driving safely despite knowingly driving over the speed limit has to do almost exclusively with Cd from his disobedience. On the contrary, the value of Ca is some amount more than zero for the person who knowingly drives dangerously. So, while both drivers are culpable, the dangerous driver is more culpable than the safe driver since the value of Ct is larger for the dangerous driver than that of the safe driver, and the difference in culpability should be taken into account when considering appropriate sanctions for the two.

4 Punishing Disobedience

The example of the two drivers, one dangerous and one safe, raises the following question. Is the safe driver culpable at all? Generally speaking, when applying the formula, Ct = Cd + Ca, it seems that we can have these four rough categories:

-

(1)

Ca > 0 and Cd > 0

-

(2)

Ca > 0 and Cd = 0

-

(3)

Ca = 0 and Cd > 0

-

(4)

Ca = 0 and Cd = 0

We can express the same idea in the following table:

Cd > 0 | Cd = 0 | |

|---|---|---|

Ca > 0 | I | II |

Ca = 0 | III | IV |

Under the first scenario (Quadrant I), there is culpability associated with the disobedience and with the underlying conduct. Under the second scenario (II), there is culpability associated with the underlying conduct but not with the disobedience. Under the third (III), the underlying conduct is not culpable, but there is culpability for the disobedience. Under the fourth, neither the underlying conduct nor the disobedience is culpable (IV). The dangerous driver then is in Quadrant I since he is knowingly driving dangerously and knowingly disobeying. The safe driver is in Quadrant III since, while he reasonably believes his driving is safe (Ca is close to zero), his knowing disobedience makes him culpable.

Or does it? Perhaps the safe driver should not be punished at all, given that he is, after all, a safe driver. Is the safe driver who disobeys the speed limit culpable? One response is that the driver who goes over the speed limit and still believes that he is driving safely may be mistaken, and his culpability lies in his placing insufficient weight on the information given to him by the speed limit.Footnote 14 But let’s set that possibility aside since the assumption here is that he reasonably believes that he is driving safely. Is there more to it than that? The answer would depend on how we answer the question whether disobedience is culpable.

There is a voluminous philosophical literature on the question whether there is a duty to obey the law, and much of this literature is critical of the idea that there is such a duty.Footnote 15 However, that debate is not (at least directly) helpful for our purposes, as the obligation to obey that is generally said not to exist is “a general obligation applying to all the law’s subjects and to all the laws on all the occasions to which they apply.”Footnote 16 In short, a proof against the existence of a general duty to obey the law is of such limited applicability that it cannot help us answer the questions when a duty to obey exists and when a violation of such a duty is culpable.

Instead of engaging in a detailed discussion, which I have done elsewhere,Footnote 17 I will use, as a starting point, a well-known argument in favor of the existence of a duty to obey the law, from John Rawls:

From the standpoint of justice as fairness, a fundamental natural duty is the duty of justice. This duty requires us to support and to comply with just institutions that exist and apply to us. It also constrains us to further just arrangements not yet established, at least when this can be done without too much cost to ourselves. Thus if the basic structure of society is just, or as just as it is reasonable to expect in the circumstances, everyone has a natural duty to do his part in the existing scheme.Footnote 18

For our purposes, such a natural duty to support just institutions would have to be rooted in the value of the state, which is the source of the criminal laws and the institutions that support the laws. A typical definition of a state is that it is a set of political institutions organized to govern a particular territory that successfully lays claim to the monopoly of legitimate violence within the territory.Footnote 19 The state does a number of things, including protecting the physical safety of those within its territory, operating a system of dispute resolution spanning from police force to administrative agencies to the judicial branch, solving coordination problems by establishing and enforcing conventions, such as rules of the road, and so on. So, given that the state exists, and given that it does these things, what moral implications follow? The answer is that it is morally wrong to interfere with institutions of the state because the state carries out valuable functions that make it possible for individuals to live normal lives as we understand normalcy today.

To bring these back to the idea of mala prohibita offenses, given all the goods that the state promotes, we can think of the criminal justice system as an effective tool for promotion of these goods. It is the state’s job to determine how to use these tools to promote the general welfare, and the citizens have a duty to support the state’s use of such tools. Antony Duff’s recent discussion of such offenses is similar. Duff proposes that, when identifying the relevant wrong in a malum prohibitum offense that at least in part relies on criminalizing disobedience of government directives, we follow this process: “[W]e must first justify the regulation in question, by showing that it efficiently serves some aspect of the common good, or averts some mischief that properly concerns the polity, and does so without laying unreasonable burdens on those who are required to obey it; we must then argue on that basis that those who breach the regulation thereby commit a censure-worthy public wrong.”Footnote 20 An important difference between Rawls’ proposal and Duff’s proposal is that Rawls’ argument cuts more broadly, as it appears to be an argument in favor of obeying all laws in a just state, whereas Duff’s proposal calls for a case-by-case approach. Given the implausibility of arguments in favor of a duty to obey all laws in all situations, it seems to me that a more promising approach is to take Rawls’ general idea of supporting the just state but apply it in a case-by-case fashion as proposed by Duff.

This discussion seems to imply, though, that the formula, Ct = Ca + Cd, is unstable, as the portion having to do with disobedience, Cd, can easily collapse into the portion having to do with not engaging in wrongful conduct, Ca. But it need not be that way, as one may choose not to engage in some conduct because engaging in that conduct is a form of failing to support just institutions, no matter what that conduct may be, aside from the wrongfulness of the underlying conduct itself. There may be times when it is difficult to know where Cd ends and Ca begins, but the fact that there may be a line-drawing problem need not mean that there is no distinction between the two.Footnote 21

One implication of this discussion is that one type of malum prohibitum offense mentioned above—strict liability offenses—cannot be justified on the grounds that mala prohibita offenses punish disobedience. The concept of disobedience implies knowingly going against a directive that one is aware of. If a person goes around in his life never killing or raping, he does not “obey” the laws that prohibit such conduct; he merely behaves in a way that does not involve committing an act that is prohibited (which could be for a variety of reasons—from conscience and empathy to indifference and laziness). The flip side of this is people who break the law without realizing it are not disobeying the law but are merely engaging in conduct that the law prohibits. This means that strict liability crimes that criminalize instances of lawbreaking where a person may be committing a crime without realizing it cannot be justified as punishment for disobedience.

5 Proportionality Determination: Some Complications

So far, we have established that: (1) crimes have mala in se and mala prohibita components; (2) the malum prohibitum component is about the wrong of disobedience; and (3) when assessing seriousness of crimes, we should consider mala in se and mala prohibita components separately. That sounds pretty straightforward, but there are a number of complications when applying this framework.

-

A.

The Problem of Identifying the Relevant Wrongs

Sometimes, because of the way laws are drafted, it is difficult to identify the exact wrong that a law targets. This is a general problem, but it is most acute with mala prohibita offenses.Footnote 22

Take drunk driving for instance. In New York, it is unlawful for a person to “operate a motor vehicle while such person has 0.08 of one percentum or more by weight of alcohol in the person’s blood.”Footnote 23 This offense is “driving while intoxicated,” and the standard this law refers to in terms of weight of alcohol in a person’s blood is “blood alcohol concentration,” commonly known as BAC.Footnote 24 Driving while intoxicated, or DWI, is a misdemeanor, and a person can be imprisoned for up to one year for committing this offense.Footnote 25

Driving is always a potentially dangerous activity, and those engaged in it should ensure that they are and will stay mentally alert and physically able while conducting the activity. And driving while drunk puts oneself and others on the road at great danger, and DWI is thus rightly considered morally wrongful.Footnote 26 However, consider the way in which New York’s DWI law is defined. The crime is not defined in terms of reckless driving but in terms of BAC.

There are several issues here. First, some people may be able to drive safely—or as safely as we generally demand from one another—with a BAC of 0.08, especially if they are driving a short, familiar route, in good driving conditions.Footnote 27 Second, people simply do not know what their BAC at a given moment is. A subjective sensation of feeling drunk or impaired is a highly unreliable guide to one’s BAC level, as people with high tolerance may not feel particularly drunk.Footnote 28 Third, the method of estimating one’s BAC level through counting the “number of drinks” one has had is unreliable given that one’s BAC level depends on a number of different factors.Footnote 29 As a result, a person who drives despite his or her BAC being 0.08 may not be aware of or feel any impairment, may not be aware that his or her BAC is above the legally permitted limit for driving, and may not in fact be impaired at all.

Now consider a driver whose BAC is above 0.08. What exactly is he doing wrong? Let us set aside the strict liability aspect of the offense.Footnote 30 Is the offense driving while knowing (or taking a risk) that he is not a safe driver due to intoxication? Perhaps this is the correct description of the relevant wrong, but it is much narrower than what the law covers, given that the law prohibits driving with a certain BAC level and people frequently underestimate their drunkenness.

Is the wrong of drunk driving, then, driving knowing that one’s BAC is above the legal limit? This is closer to the mark. Say a person knows that his BAC is 0.08. What would be wrong with driving in such a situation? Is it wrongful for such a person to drive? It would be wrongful in two different senses. At that point, if he drives, he would be taking a risk (say, substantial) of being an unacceptably dangerous driver, and that might make him culpable (for taking on a substantial and unjustifiable risk of being substantially and unjustifiably risky). What if he is confident that he can drive safely? He would still be taking the same risk, given that he (let us assume) is aware that his judgment may be too impaired to make a correct assessment of his own driving ability. (So, in other words, there is a heightened risk that his assessment of his own driving ability is incorrect, and to act in reliance on such assessment is to take the risk of being an unacceptably dangerous driver.)

Of course, people do not know what their BAC is, and, as noted above, it is difficult for an individual to know on the basis of drinks one has consumed. Perhaps then the relevant wrong is the wrong of driving after drinking. The wrongs analysis would be similar, except, instead of BAC, it is the fact of driving knowing that one has had a few drinks that makes a driver potentially culpable. If he starts driving after a few drinks, it may be the case that he is behaving dangerously. But what if he believes that he is “good to drive” because, say, he is large, has been drinking while eating food, has been drinking while rehydrating himself plenty, and has stopped drinking an hour ago? The answer may have to be partly that he cannot rely on his own judgment after having had a few drinks, which makes him potentially culpable when he drives in that state, but, at the same time, he might reasonably think that he is as safe as an ordinary sober driver, in which case it is unclear why his behavior is wrongful.

And all of this is just about Ca. What about Cd? What exactly is the directive from the state? This, too, is less than crystal clear. The law simply says “[n]o person shall operate a motor vehicle while such person has 0.08 of one percentum or more by weight of alcohol in the person’s blood as shown by chemical analysis of such person’s blood, breath, urine or saliva …”Footnote 31 Because people are not expected to know their BAC, it would be odd to see this law as directly articulating a command that is to be obeyed, though if a person happens to know his or her BAC, then that person would be under a duty to obey the law written in terms of BAC. But if “Do not drive when your BAC is 0.08” is not the command, then what is the command? The command cannot simply be, “Don’t drive when you believe you are not safe to drive,” as the law cuts more broadly than that. It seems, then, that the most likely command is, “Do not drink and drive.”Footnote 32

In sum, here are some possible descriptions of the relevant wrongs in a drunk driving case.

Ca | Cd | |

|---|---|---|

1 | Driving when intoxicated and thus dangerous | Disobeying the command, “Do not drive when you may be intoxicated and thus dangerous as a driver” |

2 | Driving knowing one’s BAC is 0.08 or above | Disobeying the command, “Do not drive when your BAC is 0.08 or above” |

3 | Driving after having consumed one or more alcoholic drinks | Disobeying the command, “Do not drink and drive” |

The point of this example is to show that the wrongs of even seemingly simple crimes like drunk driving can be described in different ways, and it is not always easy to read off a crime definition what wrongs are targeted by a given statute. And depending on what wrongs are targeted, we could arrive at different understandings about the correct culpability level. Namely, it seems that:

In other words, the wrong of driving while knowing that one is unsafe is worse than that of driving while knowing that one’s BAC is above the legal limit, which, in turn, is worse than that of driving while knowing that one has had some number of alcoholic drinks. Similarly, going against the state command not to drive as an intoxicated driver seems worse than going against the command not to drive when the BAC is 0.08 or above, which is in turn worse than going against the command not to drive after drinking.

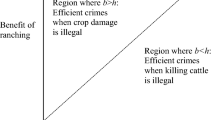

And visually, we may represent the upshot this way:

Amounts of culpability are obviously made up, but the basic idea should be clear enough. The wrong of driving after having had some drinks by itself may not be very culpable, certainly less culpable than the wrong of driving knowing that one’s BAC is at 0.08 or above, which is less culpable than the wrong of driving while too intoxicated to drive safely. Given the disparate outcomes as represented here, a challenge to overcome when devising proportionate punishments for an offense like drunk driving is knowing which wrongs are implicated.

-

B.

The Problem of Labeling

The problem of identifying the relevant wrongs could lead to the following problem of labeling. Let’s revisit the four quadrants:

Cd > 0 | Cd = 0 | |

|---|---|---|

Ca > 0 | I | II |

Ca = 0 | III | IV |

What should we do in a situation where two offenders break the same law, but the level of culpability is different for the two because Ca is different? Let’s assume that in that situation Cd > 0, so there is some culpability in disobeying. In that case, we might have two situations, Quadrants I and III, from the possibilities. The two cases might look the same from the legal perspective because they break the same law, but Ct would be different for the two individuals.

This possibility was alluded to earlier with examples of drunk driving and of two speeding drivers, one safe and one dangerous, but consider a starker example. Take two statutory rape cases, where two defendants are guilty of the crime of having sexual relations with a sixteen-year old. Say that both of them know that they are going against the law that says no sexual relations with someone under the age of seventeen, but one of them is careful about assessing the maturity level of the sixteen year old and the other one is not so careful. (We could assume that the sixteen year old is mature enough to consent in both instances—or not, as long as the level of maturity is the same in the two cases.) Both defendants would be guilty of “the same crime,” but Ct would be different for the two, since in the situation where Ca = 0, the only culpability would be Cd.

This is a familiar problem, something that can occur whenever there is an overbroad crime definition or a person engages in conduct that may be morally permissible or even desirable but cannot meet the requirements for a justification defense. In the famous case of Judy Norman, a battered woman who killed her husband after suffering from years of abuse, was convicted because her killing, even though it appears to have been necessary to avoid her own death by her husband at some point in the near future, failed to satisfy the imminence requirement of the self-defense defense.Footnote 33 Or, again, imagine a case of assisted suicide where a purposeful killing is not morally wrong but is nevertheless criminally prohibited. In both cases, those who kill knowing that what they are doing is criminal even though they see themselves as—correctly, let us assume—morally justified to kill would be disobeying the state’s directives not to kill on purpose even in such situations.

Is this a serious problem? It is possible that the problem can be minimized through the use of various discretionary devices so that the person caught in Quadrant III can be treated with leniency. The police and the prosecutor can decline to pursue such a case, a plea negotiation or a judge’s discretion can lead to a mild sentence, or a jury can even nullify.Footnote 34 At the same time, it is not clear whether the expressive dimension associated with words like “rape” and “homicide” are sensitive and fine-tuned enough to distinguish between offenders once there is a conviction, if there is a conviction. We theorists may expend a lot of effort to justify convicting offenders in situations where Ca = 0 by articulating what is wrong with disobeying, but the problem of treating two offenders of different levels of culpabilitythe same way despite differences in Ct remains.Footnote 35

-

C.

The Problem of Undercompliance

Sometimes the answer to the question whether disobedience of a law is a wrong depends on whether enough people comply with the law in question. That proposition sounds odd when it comes to mala in se offenses. As a general matter, whether one’s act of battery is wrong should not depend on whether other people are committing battery.

But take, for instance, the crime of transnational bribery. Bob is a commercial real estate agent living and working in the United States. Bob’s father owns a major commercial building and is looking for a potential buyer for the building. Bob happens to know, from his social circles, Ken, the person in charge of the sovereign wealth fund of country X. Bob asks Ken if the fund he manages would be interested in purchasing the building, and Ken tells him that the purchase can be arranged if he gets a payment in the amount of $500,000. Bob and his father arrange for the money to be given to Ken.Footnote 36 Bob is subsequently prosecuted and convicted for violating the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (“FCPA”), which prohibits, among other things:

an offer, payment, promise to pay, or authorization of the payment of any money, or offer, gift, promise to give, or authorization of the giving of anything of value … to any foreign official for purposes of influencing any act of decision of such foreign official in his official capacity.Footnote 37

What is Bob’s culpability in this? That is, why is bribery wrong? And is it a malum in se or malum prohibitum? The basic transaction seems like any other transaction; there is an exchange of things of value between two or more parties, and, as an abstract matter, it is unclear what is problematic about it. In order then to articulate what is wrong with bribery, we need an account of the proper way of conducting such exchanges, and what is at stake in conducting such exchanges in the proper way.

Deborah Hellman defines bribery “as an exchange … prohibited by the relevant decision-maker,” and says that precisely which wrong is implicated in an act of bribery depends on why the exchange is prohibited.Footnote 38 Kevin Davis explains that “[t]he most obvious problem with bribery is that it undermines state policies,” where “[t]he harm will depend on the policy being undermined.”Footnote 39 Under either account, if the state sets up a system of some kind where a state official wields some power in a domain, but if the way in which the official exercises his or her power is improperly directed by, say, a monetary payment, then whatever policy goal that is supposed to be served by giving this official this power is likely undermined. In that sense, the wrong of bribery seems to be analogous to the wrong of committing a regulatory offense, where the specific nature of the wrong will depend on the nature and purpose of the regulation.

So, in the case of the sovereign fund, we would have to know more about how investment decisions of that particular fund are supposed to be made to answer the question fully, but the basics are straightforward. Public officials who manage the sovereign wealth fund have a fiduciary duty to citizens to make decisions that are based on the merits or are at least consistent with the purpose of having such a sovereign wealth fund in the first place. In Bob’s case, since the attempt to influence the official to buy Bob’s father’s building is an attempt to short-circuit the investment decision process, he would be inducing the official to stray from his obligation to follow a process that is designed to maximize the overall value of the fund. And to the extent that Bob is seeking to have his father benefit from such a short-circuiting of the process, then he and his father would be benefiting from the fund’s activities at the expense of the intended beneficiaries of the fund, namely citizens of country X.

Put in terms of Ca and Cd, we might think of the bribery in this case as a form of stealing from beneficiaries of the fund if the idea is that the sovereign fund could have invested in some other property which would have yielded a better return,Footnote 40 and that would constitute Ca. As to Cd, the culpability arises from Bob’s using a prohibited method of inducing a sovereign wealth fund to purchase his father’s building. A difficulty arises, though, if the “proper way” of investing the funds is in theory only, but not in practice. What if, for instance, it is well known to everyone that it is quite commonplace for an official in a particular foreign country to accept bribes when it directs the government’s actions in different ways? That is, if only a minority of participants in the relevant market follows the rules of the game as written down, is it so obvious for us to conclude that a person who bribes officials because of the unwritten rule that “bribery” is business as usual is culpable?

It seems unseemly to be making an argument defending corruption, but it is easy to remind ourselves of situations where we know what the law says, but we also know that the compliance rate is low, and we feel like we alone are the ones burdening ourselves and doing more than our fair share as law-abiding citizens. The technical term for such a person is “sucker.” For example, there may be a particular street in a neighborhood where everyone parks illegally, and the chances of detection are low for whatever reason.Footnote 41 Or you may live in a society where people generally do not pay taxes that they owe. Or perhaps you are in an industry that heavily depends on government contracts, and you know that surviving as a business in that competitive environment requires paying off the right government officials since that is how “everyone does it.”Footnote 42 In such a situation, is disobedience culpable?

Perhaps an argument could be made that at that point Cd is zero because bribery appears to be lawful, and there is in fact no disobedience.Footnote 43 FCPA does provide as an affirmative defense the argument that “the payment, gift, offer, or promise of anything of value that was made, was lawful under the written laws and regulations of the foreign official’s … country.”Footnote 44 The key term there, however, is that lawfulness “under the written laws,” and, since bribery like the one described here is generally not explicitly permitted, this defense is rarely applicable.Footnote 45 In other words, there is disobedience here, and the problem is what culpability to assign to disobedience when there is widespread disobedience.

One might respond by saying that if it is the case that corruption is a problem in a society, the only way to eliminate corruption is by each individual doing his or her part, even if the non-compliance rate may be low today. That is fair enough, but if the expected non-compliance rate remains low, then an obligation for one to “play by the rules” seems to amount to an obligation to do more than one’s share and sacrifice business opportunities today so that the society overall can improve in the long run. We seem to have crossed the line between a duty of doing one’s fair share to the supererogatory duty of beneficence, and failing to do more than one’s fair share for the greater common good does not seem as culpable as failing to do one’s fair share.Footnote 46

At the same time, if it is the case that corruption is a problem, and the reason it is so difficult to combat is the dynamic of the collective action problem just noted, then it is understandable why government-imposed sanctions are necessary to make any progress on the problem of corruption. If the United States enacts the FCPA, then, to take a stand against transnational corruption and attempt to jumpstart efforts to eliminate it, individuals have a duty to obey, and the disobedience seems culpable, a violation of the duty to support just institutions.

The point here is not to settle the question of what is wrong with bribery or transnational bribery once and for all. Rather the point is that mala prohibita offenses are often enacted as a way of setting down the “rules of the road” as the government attempts to coordinate the behavior of individuals to pursue a common good, and there is a real question to how culpable a person’s disobedience of such rules might be in situations of undercompliance.

-

D.

The Problem of Knowing When the Government is Worthy of Deference

The idea that disobedience of the state is culpable, at least as described in this Essay, is rooted in the idea of doing the right thing—that is, supporting just institutions—and, as mentioned, that sort of argument does not plausibly impose a blanket obligation to obey all laws and blaming those who disobey.Footnote 47 That is, a person who fails to obey the law fails to give an appropriate normative significance to the bare existence of a law by deferring to it as something that serves the common good. This seems to imply, though, that in instances where the law seems to be unworthy of deference because it does not serve the common good or the process by which it has been created lacks credibility, the case for deferring to the law is weak. In such cases, it is possible that Cd approaches zero. If Cd is zero, then there should not be a conviction or punishment for disobedience, even though there may be clear lawbreaking through disobedience.

This is a problem on which much has already been written, and it is beyond the scope of this Essay to give it the attention it deserves.Footnote 48 The problem may be seen everywhere one looks given that it is present any time a law is misguided or the law making or law enforcement process is defective, and, in fact, every example discussed thus far may be recharacterized as the problem of laws that are defective in some way. So, instead of offering a comprehensive discussion, I will give examples from a domain where the state’s demand that citizens obey is highly compelling: national security.

Consider the following. John is a professor of engineering and an expert on plasma technology to control the flight of unmanned military drone aircrafts, and the project is being funded as a result of a contract awarded to him by the United States Air Force. Like many professors in the United States, he has graduate students from overseas, and he has one student from China and one student from Iran. John lets his students have access to the data that the project has collected. Under the Arms Export Control Act, the President of the United States is authorized to identify certain items as “defense articles and defense services” and such items cannot be exported without a license.Footnote 49 Under the regulations implementing the Act, the Department of State has designated military drones as “defense articles,” and technical data defined as “information … required for the design, development, production, manufacture, assembly, operation, repair, testing, maintenance or modification of defense articles” to be “defense articles” as well.Footnote 50 The regulations also define “export” as, among other things, a “transmission out of the United States” or “releasing or otherwise transferring technical data to a foreign person in the United States.”Footnote 51 Because the two graduate students are foreigners, John’s giving of access to data from his project to his graduate students counts as an export of “defense articles.”Footnote 52

Is John culpable in this case? It is unclear why someone like John would ignore the prohibition on making the data available to foreign students, but one can imagine that perhaps he relies on his graduate students in ways that would make giving them access to certain data useful for his work, seeks to hire the best graduate students he can find regardless of their nationality, does not think that his trust of his graduate students should vary depending on their nationality (giving the data to an American student would have been permitted, despite the purported sensitivity of the data), and thinks that the risk of benefiting Iranian and Chinese governments to the detriment of interests of the United States by giving his students access to the data is minimal to non-existent. Perhaps he may be correct on all of these, which might in the end mean that Ca is zero.

Or, consider the case of Sam, cryptocurrency expert, a United States citizen.Footnote 53 One day, he travels to China and then from there goes into North Korea to give a talk at a conference on blockchain and cryptocurrency. International Emergency Economics Powers Act (“IEEPA”) grants authority to the President of the United States “to deal with any unusual and extraordinary threat … to the national security, foreign policy, or economy of the United States, if the President declares a national emergency with respect to such threat.”Footnote 54 Presidents over time, including George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Donald Trump, declared such national emergencies with respect to North Korea through a series of Executive Orders,Footnote 55 and the Department of Treasury issued regulations banning trading with North Korea. And under the Act, it is “unlawful for a person to violate … any license, order, regulation, or prohibition” issued under the Act,Footnote 56 and a person who willfully commits such an act may be imprisoned for not more than 20 years.Footnote 57 Sam is arrested and prosecuted for violating the Executive Order 13,810, which orders that “[a]ll property and interests in property that are … within the possession or control of any United States person … are blocked and may not be transferred, paid, exported, withdrawn, or otherwise dealt in … [a]ny person determined by the Secretary of the Treasury, in consultation with the Secretary of the State … to be a North Korean person …,”Footnote 58 and the regulation that prohibits “exportation … by a U.S. person, wherever located, of any goods, services, or technology to North Korea.”Footnote 59

This law is very similar to the Arms Export Control Act, with one difference being that the IEEPA requires a declaration of a national emergency by the President. Why would Sam think there is no harm in this case? Sam may have thought it would be interesting to travel to North Korea and see it, as it is a society that is generally closed to foreign visitors. As to the content of his lecture, he may have thought it is not a big deal to give a generic talk on cryptocurrency at a conference (assuming that this is all he did) if the talk covers basic information that is easily available from various educational sources, and he may think that there is no culpability in discussing an emerging technological tool like cryptocurrency with anyone, even if that person happens to be in North Korea. Again, he also may be correct, which might in the end mean that Ca is zero.

But what about Cd in these two cases? Are these situations where obedience to state directives is called for? It seems to me that these are the crimes that we should think of as crimes of “usurpation” or “foreign relations vigilantism.”Footnote 60 The problem with these kinds of acts with national security implications is that they cross the boundaries that are set up to secure the core institutional resources the state requires to protect itself. When a citizen participates in efforts to undermine the core institutional resources the state requires to protect itself, the citizen disturbs the way in which power is distributed within the polity and enters a domain of exclusive governmental power. The relevant wrong thus should be thought of as usurpation of state power, and it is a specific instantiation of the general duty to support just institutions. So, we might think of violations of the Arms Export Control Act and the IEEPA as, at least, crimes of disobedience. These also seem like the kinds of situations where individual citizens are unlikely to have superior knowledge as to what exactly will hurt or not hurt national security, and individuals should feel justified in acting contrary to the laws only when they are nearly certain that the government is wrong to think there is a risk of harm to national security from such acts.Footnote 61

Despite all such good reasons not to commit these acts, whether a person can be considered culpable or not seems to turn at least partly on whether the United States government is entitled to this sort of respect in these matters. And the judgment that these individuals are culpable for their conduct is most plausible when the political leaders themselves are credible actors whose judgments are entitled to deference. The question all of this raises, though, is what to think of situations where Cd is zero, at least where the case can be made that disobeying the law in a particular situation is not culpable because, for instance, the President cannot be trusted to have acted with the best interests of the United States in these matters.

Currently, we do not have a lot of options where that arises. Again, as mentioned above, it is possible that discretionary devices held by certain legal actors like the prosecutor (declining to prosecute) or the judge (sentencing mitigation or narrowing construction of lawsFootnote 62) or the jury (nullifying) perhaps could take care of these problems, but would such opaque devices be enough? It seems that what we may need, for instance, is a venue in which a defendant could make the case that Cd is zero, and that therefore there is no duty to obey and he or she should thus not be convicted. But could we devise such a venue? There are reasons to think that a proceeding where the government openly acknowledges (even if only through a judicial ruling) that there may be good reasons not to obey the law is highly unlikely.Footnote 63

To say the least, the principle of proportionality is an ideal that comes under strain in poorly functioning and untrustworthy states, especially when it comes to mala prohibita offenses. And even in well-functioning states, the legal system’s inability or reluctance to accommodate a forum in which the state can acknowledge the ways in which it is not worthy of its citizens’ deference presents a problem for those who are committed to the principle.

6 Conclusion

This Essay has advanced the following two propositions. First, while many different kinds of crimes can be identified as mala prohibita offenses, proper proportionality determinations require breaking offenses down into malum prohibitum and malum in se components and assigning culpability levels to each and then combining them. Second, because the malum in se component and the malum prohibitum component track different types of wrongs, a number of difficulties arise when applying the framework, many of which are due to the fact that the malum prohibitum component tracks the wrong of disobeying the state.

Notes

15 USC s. 80b-3 (2019) (“[I]t shall be unlawful for any investment adviser, unless registered under this section, … to make use of the mails or any means or instrumentality of interstate commerce in connection with his or its business as an investment adviser.”); 15 USC s. 80b-2 (2019) (“‘Investment adviser’ means any person who, for compensation, engages in the business of advising others … as to the advisability of investing in, purchasing, or selling securities …”); 15 USC s. 80b-17 (2019) (“Any person who willfully violates any provision of this subchapter, or any rule, regulation, or order promulgated by [the Securities and Exchange] Commission under authority thereof, shall, upon conviction, be fined not more than $10,000, imprisoned for not more than 5 years, or both.”).

“Proportionality” can mean different things, see, e.g., Youngjae Lee, “The Constitutional Right Against Excessive Punishment”, Virginia Law Review 91 (2005): pp. 737–741, and this Essay assumes that the principle of proportionality means that the harshness of the punishment should reflect our level of condemnation or disapproval of the criminal act. Youngjae Lee, “Why Proportionality Matters”, University of Pennsylvania Law Review 160(6) (2012): pp. 1836–1840. A punishment would be excessive, then, if the degree of condemnation indicated by the amount of punishment were too high relative to the criminal’s culpability. A punishment also would be excessive in situations where it is imposed on a person who has not committed any acts for which the kind of condemnatory expression that accompanies criminal sanction would be appropriate. A corollary to all of this is that the harshness of the punishment should increase as the appropriate level of condemnation or disapproval increases, which in turn should increase as the gravity of the crime increases.

Larry Alexander and Kimberly Kessler Ferzan, Reflections on Crime and Culpability: Problems and Puzzles (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018), p. 83; Larry Alexander and Kimberly Kessler Ferzan, Crime and Culpability: A Theory of Criminal Law (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009), p. 309.

Alexander and Ferzan, Reflections on Crime and Culpability: Problems and Puzzles, pp. 83–84.

See, e.g., R.A. Duff, “Perversions and Subversions of Criminal Law”, in R.A. Duff et al. (eds.), The Boundaries of the Criminal Law (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), pp. 88–112; R.A. Duff and S.E. Marshall, “‘Abstract Endangerment’, Two Harm Principles, and Two Routes to Criminalisation”, Bergen Journal of Criminal Law and Criminal Justice 3(2) (2015): pp. 149–157. Alexander and Ferzan call such offenses “preemptive crimes.” Alexander and Ferzan, Reflections on Crime and Culpability: Problems and Puzzles, p. 84 n.2; Alexander and Ferzan, Crime and Culpability: A Theory of Criminal Law, pp. 309–310. Douglas Husak calls them “offenses of risk prevention.” Douglas Husak, Overcriminalization: The Limits of the Criminal Law (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), p. 38.

31 USC. s. 5316(a) (1986) (“[A] person … shall file a report … when the person … knowingly … transports, is about to transport, or has transported monetary instruments of more than $10,000 at one time … from a place in the United States to or through a place outside the United States; or … to a place in the United States from or through a place outside the United States.”); 31 USC s. 5316(b) (1986) (“A report under this section shall be filed at the time and place the Secretary of the Treasury prescribes.”); 31 USC s. 5322 (2001) (“A person willfully violating this subchapter or a regulation prescribed or order issued under this subchapter … shall be fined not more than $250,000, or imprisoned for not more than five years, or both.”); see also United States v. Bajakajian, 524 U.S. 321 (1998).

See generally Sandra Guerra Thompson, “The White-Collar Police Force: ‘Duty to Report’ Statutes in Criminal Law Theory”, William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal 11(3) (2009): pp. 3–65; Sungyong Kang, “In Defense of the ‘Duty to Report’ Crimes”, UMKC Law Review 86 (2017): pp. 361–403; Gerard E. Lynch, “The Lawyer as Informer”, Duke Law Journal 491 (1986): pp. 520–521.

18 USC s. 1957 (2012) (criminalizing engaging in “a monetary transaction in criminally derived property of a value greater than $10,000 [where the property] is derived from specified unlawful activity”).

Morissette v. United States, 342 U.S. 246 (1952); see generally Darryl Brown, “Public Welfare Offenses”, in Markus Dubber and Tatjana Hörnle (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Criminal Law (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), pp. 862–883.

See, e.g., 31 USC s. 5322 (2001); 15 USC s. 80b-17 (1975); see also Richard Lazarus, “Meeting the Demands of Integration in the Evolution of Environmental Law: Reforming Environmental Criminal Law”, Georgetown Law Journal 83(7) (1995): p. 2441 (“[A]t the federal level, Congress has virtually criminalized civil law by making criminal sanctions available for violations of otherwise civil federal regulatory program.”).

A.P. Simester, “Is Strict Liability Always Wrong?”, in A.P. Simester (ed.), Appraising Strict Liability (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), pp. 21–50; Stuart Green, “Six Senses of Strict Liability: A Plea for Formalism”, in A.P. Simester (ed.), Appraising Strict Liability (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), pp. 2–9.

Others have made similar suggestions. See, e.g., Douglas Husak, “Malum Prohibitum and Retributivism”, in R.A. Duff & Stuart P. Green (eds.), Defining Crimes: Essays on the Special Part of the Criminal Law (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005): pp. 74–82 (describing “hybrid offenses”); R.A. Duff, The Realm of Criminal Law (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), pp. 313–322 (“pure and impure”); Stuart P. Green, Lying, Cheating, and Stealing: A Moral Theory of White-Collar Crime (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), p. 120 (“mala in se and mala prohibita qualities”).

This formula does not preclude the possibility of various traditional excuse defenses, such as insanity, duress, and lack of voluntary conduct. In such instances, the values of these variables would amount to zero. What about justification defenses? Is it possible for these numbers to be “negative” in the sense that reasons to engage in these lawbreaking activities outweigh the reasons not to? In such cases, one may be “doing the right thing,” and one who does the right thing of course seems to be not culpable. Two points about this. It is possible for all the numbers to “zero out” because a lawbreaker indeed does the right thing, especially if the relevant conduct meets the requirements of legally recognized justification defenses like self-defense and necessity. However, there may be times when a person appears to have “done the right thing” but still fails to meet the requirements of justification defenses. Then what? In such instances, while Ca is zero, there would still be culpability for disobedience. See infra for more on this. I thank Mihailis Diamantis for raising this question.

R.A. Duff, “Crime, Prohibition, and Punishment”, Journal of Applied Philosophy 19(2) (2002): p. 104 (discussing “civic arrogance”); Alexander and Ferzan, Crime and Culpability: A Theory of Criminal Law, p. 311.

See, e.g., John Simmons, Moral Principles and Political Obligations (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1979).

Joseph Raz, “The Obligation to Obey the Law”, in Joseph Raz (ed.), The Authority of Law: Essays on Law and Morality (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979), p. 234.

Youngjae Lee, “Recidivism as Omission: A Relational Account”, Texas Law Review 87(3) (2008), pp. 1–51; Youngjae Lee, “Punishing Disloyalty? Treason, Espionage, and the Transgression of Political Boundaries”, Law and Philosophy 31(3) (2012): pp. 299–342.

John Rawls, A Theory of Justice (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1971), p. 115.

Leslie Green, The Authority of the State (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988); George Klosko, Political Obligations (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005).

Duff, The Realm of Criminal Law, p. 333.

One place where the legal system has made distinctions of this kind is in the phrase “moral turpitude” in immigration law. 8 USC s. 1227(a)(2)(A)(i) & (ii) (2008) (authorizing removal of aliens convicted of crimes of moral turpitude in certain instances). In Bakor v. Barr, the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals of the United States ruled that failing to register as a sex offender as required by law is a crime of moral turpitude because “[a]n offender who knowingly fails to register as a sex offender … evades a regulation that is designed to protect vulnerable victims against recidivist sex offenders, and does so with a culpable mental state.” Bakor v. Barr, 958 F.3d 732, 738 (8th Cir. 2020). Some courts that have disagreed with the Bakor court have relied on a similar distinction. See, e.g., Mohamed v. Holder, 769 F.3d 885, 889 (4th Cir. 2014) (“The failure to register as a sex offender … do[es] not implicate any moral value beyond the duty to obey the law.”); Totimeh v. Attorney General of the United States, 666 F.3d 109, 116 (3rd Cir. 2012) (“[F]ailing to register … as a predatory offender is not … an inherently despicable act.”); Efagene v. Holder, 642 F.3d 918, 926 (10th Cir. 2011) (holding that failure to register as a sex offender is not “inherently base, vile, or depraved”). I thank Craig Lerner for alerting me to this line of cases.

For a discussion, see Gabriel S. Mendlow, “The Elusive Object of Punishment”, Legal Theory 25(2) (2019): pp. 117–125.

NY Vehicle & Traffic Laws s. 1192 (2014).

Ibid.

NY Vehicle and Traffic Laws s. 1193 (2012). Moreover, if a person drives while intoxicated with a child under the age of fifteen in the vehicle as a passenger, then the person is guilty of a felony, and can be imprisoned for up to four years. NY Penal Law s. 70(2)(e) (2019).

But see Douglas Husak, “Is Drunk Driving a Serious Offense?”, Philosophy & Public Affairs 23(1) (1994): pp. 52–73.

In a study designed to test the effects of alcohol on driving ability, “parameters differed distinctly between the BAC conditions depending on the underlying scenario.” Ramona Kenntner-Mabiala et al., “Driving Performance Under Alcohol in Simulated Representative Driving Tasks”, Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 35(2) (2015): p. 140. The test subjects “drove slightly faster under alcohol than under placebo only in the difficult tracking scenario.” Ibid. at 139. Difficult roads resulted in the number of lane departures increasing for those under the influence of alcohol, “whereas in easy tracking scenarios, no lane departure was observed at all.” Ibid. at 140. Difficult scenarios testing the standard deviation of lane position—which refers to swaying from the middle of the road—resulted in a ceiling effect, as sober test subjects had just as much trouble driving in such conditions as drunk subjects. Ibid. See also Arne Helland et al., “Comparison of Driving Simulator Performance with Real Driving After Alcohol Intake: A Randomised, Single Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Cross-Over Trial”, Accident Analysis & Prevention 53 (2013): p.13 (showing that while increasing BAC increased drivers’ tendency to “weave” on the road overall, the effect increased as the difficulty of the test track increased). Circadian sleep propensity can also affect the riskiness of driving after alcohol consumption. See Sergio Garbarino et al., “Circadian Sleep Propensity and Alcohol Interaction at the Wheel”, Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine 12(7) (2016): p. 1011 (finding that increased sleep propensity led to a higher likelihood of motor vehicle crashes when drunk driving). How unsafe a driver with a high BAC is seems to vary depending on the age and sex of the driver, too. Paul L. Zador et al., “Alcohol-Related Relative Risk of Driver Fatalities and Driver Involvement in Fatal Crashes in Relation to Driver Age and Gender: An Update Using 1996 Data”, Journal of Studies on Alcohol 61(3) (2000): pp. 387–395, 393 (finding that “the relative risk decrease[s] with increasing driver age at every BAC level, for both men and women” and that for the 16–20 age group, “women had lower relative risk than men at every BAC”).

One study reported that “more than one third of participants legally intoxicated for driving purposes (37%) reported feeling no buzz or slightly buzzed…,” and “16% of participants who reported no buzz were legally impaired for driving purposes….” Matthew E. Rossheim et al., “Feeling No Buzz or a Slight Buzz Is Common When Legally Drunk”, American Journal of Public Health 106(10) (2016): p. 1761.

The “number of drinks” consumed is hardly the only relevant factor to BAC; how quickly the drinks were consumed, the amount of water consumed, whether food was consumed, and the type of alcohol consumed all affected the BAC and the time to peak BAC. Steven M. Teutsch et al., Getting to Zero Alcohol-Impaired Driving Fatalities: A Comprehensive Approach to a Persistent Problem (Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press, 2018), p. 177. In fact, the amount of fluid intake consumed with alcohol had a higher impact on BAC than the amount of alcohol intake. Julian E. Dilley et al., “Alcohol Drinking and Blood Alcohol Concentration Revisited”, Alcoholism Clinical and Experimental Research 42(2) (2018): pp. 260–269 (2018). BAC increased with the concentration of alcohol, rather than the number of doses of alcohol, effectively proving “that alcohol concentration can influence BAC independent of alcohol dose.” Ibid. Individualized factors were also relevant. See, e.g., Shunji Oshima, “Individual Differences in Blood Alcohol Concentrations After Moderate Drinking Are Mainly Regulated by Gastric Emptying Rate Together With Ethanol Distribution Volume”, Food and Nutrition Sciences 3(6) (2012): pp. 732–737 (2012) (identifying individual differences in “gastric emptying rate” as a significant factor in explaining individual differences in BAC after consuming alcohol). There also appears to be a male–female difference in the rate at which alcohol consumption impacts the BAC. Martin S. Mumenthaler et al., “Gender Differences in Moderate Drinking Effects”, Alcohol Research & Health 23(1) (1999): p. 55.

Mendlow, “The Elusive Object of Punishment”: p. 124.

NY Vehicle and Traffic Law s. 1192(2) (2014).

In this way, this law is similar to statutory rape laws, the message of which may not be, “Do not have sexual relations with someone under the age of consent as legally specified,” but rather, “Do not have sexual relations with a youngish looking person.”

For a discussion, see Kimberly Kessler Ferzan, “Defending Imminence: From Battered Women to Iraq”, Arizona Law Review 46 (2004): pp. 233–235; Benjamin Zipursky, “Self-defense, Domination, and the Social Contract”, University of Pittsburgh Law Review 57 (1996), pp. 579–614.

Cf. Duff, The Realm of Criminal Law, pp. 67–69.

Stuart Green has discussed this problem and has called it “the problem of wrongfulness conflation.” Stuart Green, “Legal Moralism, Overinclusive Offenses, and the Problem of Wrongfulness Conflation”, Criminal Law & Philosophy 14(3) (2020): pp. 417–430. In the statutory rape context, a solution Green suggests is to separate out the two kinds of offenders by convicting them under different statutes, both of which criminalize sex with a juvenile, but one of them has the element “exploitative sex” and the other one does not. The more serious charge would be then “exploitative sex with a juvenile,” and either “non-exploitative sex with a juvenile” or simply “sex with a juvenile” would be the less serious charge. This kind of distinction may improve things, though it is unclear by how much. The state would be now placed in the awkward position of convicting a person that it considers to have engaged in sexual relations with a juvenile in a “non-exploitative” way, in which case it does not seem like there is a wrong to punish at all. If the state tries to avoid the implication by simply not using the “exploitative sex” law and convicts everyone under the law that does not mention the idea of “exploitative sex,” then the problem of wrongness conflation returns. Or, we may end up in that situation through the process of plea bargaining, where the state charges individuals with the “exploitative sex” charge and offers to charge the defendants with the lesser crime in exchange for a guilty plea. The problem of wrongness conflation, again, returns in that world.

This description is roughly based on United States v. Joo Hyun Bahn, 16 CR 831 (S.D.N.Y. 2017), but with many modifications. In the actual case, there was a “middle man” between the defendant and the sovereign wealth fund, and it turned out the “middle man” did not know anyone at the fund and was defrauding the defendant. The defendant nevertheless was convicted for violating the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act after pleading guilty and was sentenced to six months in prison.

15 USC s. 78dd-2 (1998).

The full formulation by Hellman is “an exchange across boundaries prohibited by the relevant decision-maker” where “an exchange across boundaries” is defined as an exchange of “values … of different types,” such as an “exchange of money for a vote.” Deborah Hellman, “Understanding Bribery”, in Larry Alexander and Kimberly Kessler Ferzan (eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Applied Ethics and the Criminal Law (Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019): pp. 147–148. In the hypothetical being discussed here, a monetary payment is being made in order for a sovereign fund to make a monetary payment to purchase a building, so it is not clear whether this is “an exchange across boundaries” in Hellman’s terms. I will set that complication aside here, given it is clear that the hypothetical describes an instance of bribery, even if the exchange is not “across boundaries.”

Kevin Davis, Between Impunity and Imperialism: The Regulation of Transnational Bribery (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019), p. 60.

Cf. ibid., pp. 60 and 236 (describing the harm of a bribery scheme in Haiti to consist of “the Haitian government... receiv[ing] less money than it should have” and calling it a form of stealing from ordinary Haitians).

I noticed, when I lived in Florence some years ago, that the locals interpreted the “24-h no parking” sign as “free parking” (as in there were no meters to feed) in certain spots, and it was important to know where that was the case and where that was not.

Cf. Douglas Husak, “The ‘But-Everyone-Does-That!’ Defense”, Public Affairs Quarterly 10(4) (1996): pp. 307–334.

I thank Kimberly Ferzan for raising this question.

Criminal Division of the U.S. Department of Justice and the Enforcement Division of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, “A Resource Guide to the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act” (2d ed., 2020): p. 23.

Ibid., p. 24 (“In practice, the local law defense arises infrequently, as the written laws and regulations of countries rarely, if ever, permit corrupt payments.”).

Cf. Laura Valentini, “The Natural Duty of Justice in Non-Ideal Circumstances: On the Moral Demands of Institution Building and Reform”, European Journal of Political Theory (2017): pp. 6–12 (considering citizens’ obligations in situations of “moderate expected non-compliance” and “pervasive expected non-compliance”).

Laura Valentini, “The Content-Independence of Political Obligation: What It Is and How to Test It”, Legal Theory 23(2) (2018): p. 135.

See, e.g., Duff, The Realm of Criminal Law, pp. 127–137, 167–182, 225–231; Youngjae Lee, “Criminalization, Legal Moralism, and Abolition”, University of Toronto Law Journal 70(2) (2020): pp. 209–211; Dan Markel, “Retributive Justice and the Demands of Democratic Citizenship”, Virginia Journal of Criminal Law 1(1) (2012): pp. 14–17 (distinguishing between “dumb but not illiberal” laws, “illiberal” laws, and “spectacularly dumb” laws); Jeffrie G. Murphy, “Marxism and Retribution”, Philosophy & Public Affairs 2 (1973): pp. 217–243.

22 USC s. 2778 (2014).

22 CFR s. 120.10 (2014).

22 CFR s. 120.17 (2019).

This description is based on United States v. Roth, 628 F.3d 827 (6th Cir. 2011).

This description is based on United States v. Virgil Griffith, 19 Mag 10,987 (S.D.N.Y. 2019).

50 USC s. 1701 (1977).

Executive Order 13,466, “Continuing Certain Restrictions with Respect to North Korea and North Korea Nationals” (June 26, 2008); Executive Order 13,551, “Blocking Property of Certain Persons with Respect to North Korea” (August 30, 2010); Executive Order 13,570, “Prohibiting Certain Transactions with Respect to North Korea” (April 18, 2011); Executive Order 13,687, “Imposing Additional Sanctions with Respect to North Korea” (January 2, 2015); Executive Order 13,722, “Blocking Property of the Government of North Korea and the Workers’ Party of Korea, and Prohibiting Certain Transactions with Respect to Korea” (March 15, 2016).

50 USC s. 1705(a) (2007).

50 USC s. 1705(c) (2007).

Executive Order 13,810, “Imposing Additional Sanctions With Respect to North Korea” (September 20, 2017).

31 CFR s. 510.206 (1980).

For a more sustained defense, see Lee, “Punishing Disloyalty? Treason, Espionage, and the Transgression of Political Boundaries”: p. 299.

Cf. Cecile Fabre, “The Morality of Treason”, Law and Philosophy 39 (2020): p. 446.

Julie Rose O’Sullivan, “Skilling: More Blind Monks Examining the Elephant”, Fordham Urban Law Journal 39(2) (2011): p. 343.

One indicator is the legal system’s conflicted stance on the practice of jury nullification, which is recognized as a feature, not a bug, in the system yet is unmentionable through official channels during a trial. See Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145, 187 (Harlan, J., dissenting) (“A jury may, at times, afford a higher justice by refusing to enforce harsh laws.”); United States v. Thomas, 757 F.2d 606, 614 (“We categorically reject the idea that, in a society committed to the rule of law, jury nullification is desirable or that courts may permit it to occur when it is within their authority to prevent.”).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Thanks to John Hasnas for organizing the conference on proportionality in criminal law where this paper was presented. Thanks also to participants at the conference, including Larry Alexander, Mihailis Diamantis, Kimberly Ferzan, John Hasnas, Craig Lerner, and Gabe Mendlow, for helpful comments, and to Chrystel Yoo and Susu Zhao for research and editorial assistance.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, Y. Mala Prohibita and Proportionality. Criminal Law, Philosophy 15, 425–446 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11572-021-09576-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11572-021-09576-7