Abstract

Multilateral development banks (MDBs) have proved to be one of the most popular and enduring forms of international organization ever created, in large part because of their unique financial model. MDBs raise most of the resources needed for operations from international capital markets rather than government budgets, which greatly increases their financial capacity and attractiveness to member governments. However, this model has a trade-off: MDBs must pay close attention to the perceptions of bond investors, who have little interest in development goals. This paper explores the influence of credit rating agencies (CRAs) on MDB operations, based on an analysis of the methodologies used by CRAs to evaluate MDBs and interviews with MDB financial staff and CRA analysts. The study demonstrates that the methodology used by Standard and Poor’s seriously undervalues the financial strength of MDBs, limiting their ability to pursue their development mandate. These findings suggest that MDB dependence on capital market financing may weaken the ability of major shareholder governments to fully control MDB activities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

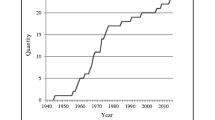

Multilateral development banks (MDBs) represent one of the most popular types of international organization created in the post-World War II era. Over 20 MDBs currently operate in the world, and two more—the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and New Development Bank—began operations in 2016.

A key reason for the proliferation of MDBs as a specialized form of international organizational is their unique and powerful financial model. Member governments invest a relatively small amount of shareholder capital to establish the financial foundations of an MDB, and the MDB in turn raises the majority of resources for development projects by borrowing on international capital markets. For example, the World Bank’s main lending window borrowed US$63 billion in FY2016, mainly in the form of bonds.Footnote 1

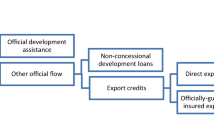

Because the major MDBs have high bond ratings, they are able to borrow very inexpensively, meaning they are able to on-lend to developing countries at attractive terms, even including a margin above their own funding costs to pay for MDB administrative expenses. Thus, government shareholders can have a very significant developmental impact (in financial terms, at least) with a small budgetary outlay (Table 1)—a very appealing organizational model. This does not pertain to the “concessional” lending window for the poorest countries—like the World Bank’s International Development Association (IDA)Footnote 2—and numerous MDB-administered trust funds, which are funded mostly by direct donations from wealthy governments.

While MDBs have been very successful in channeling private capital toward development projects, their financial model does come with trade-offs. MDB management must be sensitive to the needs and perceptions not only of government shareholders, but also of the bond market actors who supply much of their operating resources. This gives MDBs a degree of operational autonomy from government “principals” compared to international organizations funded directly by budget allocations (like the United Nations, for example), and it also gives MDBs a reason to act in ways that may not always align with their development mandate.

What sort of pressure do capital markets exert over MDBs, if any? Bond markets certainly have a strong influence on governments. Rising sovereign bond yields driven by the perceptions of capital market players can easily force a government to change fiscal, exchange rate or monetary policies, despite substantial political resistance, and even came close to destroying the Euro. Not for nothing did U.S. political consultant James Carville once comment that if reincarnation existed, “I want to come back as the bond market. You can intimidate everybody” (Wall Street Journal, February 25, 1993).

This paper explores the relationship between capital markets and MDBs, and seeks to answer the following linked questions: does dependence on the perceptions of bond investors influence the ability of MDBs to undertake the development mandate dictated by government shareholders, and if so, in which ways? It does so by examining the methodology of credit rating agencies (CRAs) as key gatekeepers for MDB access to capital markets.

The findings indicate that CRAs—and in particular, Standard & Poor’s (S&P)—are utilizing evaluation methodologies that significantly underestimate the financial strength of MDBs. In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, CRAs created new methodologies that evaluate MDBs using a similar approach to how they evaluate commercial banks, although MDBs are non-profit development institutions. As a result, to retain their AAA bond rating, major MDBs are i) restricting their overall capacity to make use of their balance sheet for development projects and ii) limiting lending to some borrowing countries facing economic difficulties. CRAs—private, for-profit companies—have become the de facto regulator for the most important set of international organizations promoting global development.

This highlights the “Achilles heel” of MDBs: they must pay close attention to the perceptions of bond buyers and, especially, CRAs, which have no particular interest in or allegiance to the MDB mission of promoting development and reducing poverty. This, in turn, incentivizes MDB staff to sometimes act in ways not in accordance with their developmental mandate, to ensure continued access to their key source of funding. As the saying goes, “He who pays the piper calls the tune.” The study findings have important implications for a fuller understanding of how and why MDBs make decisions on lending and other operational policies.

The paper is structured as follows. The theoretical underpinnings of the research are described in Section 2, followed by a justification of the case selection and an outline of the methodological approach in the third section. Section 4 examines the internal logic and consistency of three key aspects of CRA methodology for MDBs, while Section 5 provides evidence for how this methodology has impacted MDB operations. The sixth section concludes.

2 Theoretical considerations

The main intention of the paper is to contribute to the academic literature on MDBs by focusing on how their financial model influences their behavior. Scholarship on the financial pressures faced by MDBs is relatively limited. Kapur et al. (1997) present rich historical information on the interplay between financial and developmental considerations at the World Bank and Humphrey (2016) compares the historical and financial trajectory of three MDBs. Mohammed (2004), Woods (2006) and Humphrey (2014) consider political implications of MDB financial policies in more recent contexts. Gould (2006) paints a fascinating picture of the interplay between financial markets and IMF activity, although in a way that differs fundamentally from the current paper, which focuses on the way MDBs raise their own operating resources.

However, little research has focused on the fact that MDBs obtain most of their resources from capital markets, and what that might mean. As noted by Barnett and Coleman (2005)—following an earlier study focusing on resource dependence by Pfeffer and Salancik (1978)—international organizations (IOs) must adapt to secure the resources needed to survive, even if they end up acting in ways that does not always perfectly match the goals of the organization: “The more dependent they are on others, the more likely IOs will alter their activities in a way that conforms to these external demands and standards” (Barnett and Coleman 2005: 599). This suggests that MDBs will be highly responsive to capital market requirements, to ensure a continued flow of resources.

Dovetailing with this view of the IO as a strategic actor seeking to ensure access to resources is the extensive literature viewing IOs as “agents” constituted by a group of “principals” (nation states) to undertake certain specific tasks (see among others Hawkins et al. 2006, Lyne et al. 2009, or Lake 2007). The principal-agent (PA) framework has proved extremely useful in helping highlight i) the mechanisms used by principals to attempt to control the agents; and ii) the fact that IO agents sometimes pursue agendas that do not always match up with what government principals desire. PA-oriented research on MDBs has thus far not explored how capital market financing might impact these dynamics.

One of the key mechanisms for principals to enforce their authority over agents is control over resources. As noted by Lake (2007): “A grant of authority from the principal to the agent must be conditional and revocable, and the principal retains all residual rights of control including the right to veto actions by the agent either directly or indirectly by cutting funding or other means” (p. 207, italics added). For most IOs, operating resources are controlled entirely by the principal. Hence, for example, the United States can apply direct and immediate pressure on the United Nations by threatening to withhold its budgetary contribution.

In the case of MDBs, however, the ability of government principals to utilize the purse strings to enforce their preferences is diluted. Governments do have some control over MDB resources—notably during capital increases (when governments increase their shareholding to expand MDB lending capacity) and replenishing concessional lending windows for the poorest countries. Numerous MDB researchers, including Babb (2009), Kapur (2000), Nielson and Tierney (2003) and Woods (2006), have highlighted how major MDB policy changes were pushed through during capital increase or replenishment round negotiations. But the working capital used for day-to-day operations of MDBs comes not from shareholders, but rather capital markets. This, in turn, makes it more difficult for principals to use resource access as a mechanism to control MDBs.

The fact that capital market financing weakens the ability of government principals to control MDBs also influences the incentives facing MDB agents. PA literature has two basic sets of explanations as to why IO agents would act against the wishes of their principals. The rationalist approach—building on the early work of Niskanen (1971)—sees IOs as self-interested bureaucracies, focused on their own material power. This view is expressed succinctly by Vaubel (2006): “The international agents are interested in the survival and growth of their organization: more staff, a larger budget and increasing competencies.” Recognizing that this view is unlikely to be the whole story, other scholars have considered more sociological-constructivist explanations emphasizing bureaucratic authority, knowledge creation and organizational norms (Barnett and Finnemore 2004; Nielson et al. 2006; Weaver 2008).

The need to ensure access to capital market financing adds a new dimension to the incentives of MDB agents—one that fits conceptually in the rationalist approach of bureaucratic interests. A strong relationship to capital market actors gives MDB staff a substantial degree of autonomy from and authority over government shareholders.Footnote 3 MDB staff—not member governments—is responsible for ensuring continued access to capital market financing. Governments have the final say on financial policy, but MDB staff manages financial ratios, holds meetings with CRAs and undertakes bond issues. Much of this is arcane information that shareholder representatives do not fully understand. One World Bank Executive Director described a discussion with the World Bank chief financial officer on a proposed financial policy change: “He said the rating agencies could be impacted, that we might lose our AAA, and we [the executive directors] couldn’t say much about it. We are sort of in their hands. They [Treasury] tell you a very technical story, and in the end we have to trust them.”Footnote 4

It should come as no surprise, then, that MDB staff works very hard to maintain strong relationships with CRAs, major bond buyers and other capital market actors. To be sure, MDB staff is delegated to do this work by government shareholders, so it also forms part of their mandate as agents. But it is clear that these relationships have given MDBs a freedom to maneuver and autonomy from their principals beyond that available to a standard, budget-funded IO.Footnote 5 As Kapur (2000, p. 32) notes in his comparison of the UN and MDBs, “Financial autonomy is the key to bureaucratic autonomy.”

Thus, the dependence on capital market financing is an intervening variable that should be accounted for in applying PA frameworks to analyze MDB operations. The MDB financial model weakens the control of government principals over MDB agents and gives the agents an additional incentive to sometimes act in ways that do not match up with the development goals set by principals.

Before moving on to the empirical section of the paper, it is worth considering on a conceptual level the role played by CRAs in evaluating MDBs. Understanding the actions of CRAs themselves is not the focus of this paper—rather, they are an exogenous factor impacting MDBs, which are the main objects of study. It is nonetheless worthwhile briefly considering the question of CRA motivations in relation to MDBs.

As numerous studies have highlighted (Shorter and Seitzinger 2009; Bolton et al. 2012; Kruck 2016; and Barnett and Coleman 2005), CRAs have a key formal role as capital market gatekeepers for several reasons. Their status is enshrined in financial regulation in Europe and the U.S. as a component of how capital adequacy is measured under the Basel guidelines. As well, CRAs have a very powerful role in shaping the perceptions of many bond investors who do not have the time and information to easily evaluate debt securities themselves—particularly MDBs, about which most bond investors know little. Lastly, certain institutional investors like pension funds and central banks are required by their mandates only to invest in securities with a minimum bond rating from the CRAs.

Combining the insights of existing research on CRA behavior with the peculiarities of the MDB case, one can propose a plausible explanatory narrative as to why CRAs might have implemented a restrictive rating methodology for MDBs in recent years. It is important to emphasize that the interpretation below would require further research to substantiate and deepen—the empirical evidence presented later in this paper does not bear directly on the motivations of CRAs.

The 2008 crisis and ensuing criticism of CRAs led directly to an increase in external pressure from regulators to tighten methodologies (as described in Kruck 2016), as well as likely a need to recover reputation to ensure prolonged future business in the way Mathis et al. 2009 suggest. Because the 20-odd MDBs represent a very small share of CRA revenue, they have little leverage over CRAs as customers, reducing the financial incentives CRAs might have to over-rate MDB securities described by Bolton et al. 2012. This makes it easier for CRAs to use them as a convenient example to demonstrate their rating stringency and gain credibility in the markets as described by Mathis et al. 2009. Further, as will be explored in more detail below, the particular logic of the quantitative model employed by S&P has led to perverse outcomes weighing on MDB ratings, similar to those outlined by Choi and Hwang (2012) for other asset classes.

3 Case selection and methodology

This paper focuses on the impact of CRA methodologies on the non-concessional lending windows of four MDBs: the World Bank, Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), Asian Development Bank (AsDB) and African Development Bank (AfDB). These are the paradigmatic multilateral development banks built following the end of World War II, with a roughly similar approach to addressing global development. The World Bank is by far the best-known MDB, while the other three are the standard-bearer regional MDBs in the Bretton Woods system, modeled direct on the World Bank and with many of the same shareholders, although each with its own particular regional characteristics and trajectory. They are also among the select group of MDBs with the highest possible AAA bond rating from all the major CRAs,Footnote 6 which confers substantial advantages for capital market funding not available to lower-rated bond issuers.Footnote 7

With a AAA rating, the major MDBs can fund themselves at very low interest rates in capital markets compared to other issuers, which in turn allows them to offer loans at very low rates to borrowers, even after adding a margin to cover MDB administrative expenses. AAA status, and the prestige this carries among bond investors around the world, allows the major MDBs to opportunistically raise funding around the globe when conditions are advantageous, further bringing down funding costs (and hence loan charges to borrowers). These strengths are accentuated even further during times of global crisis, when investors flee for quality assets like AAA bondsFootnote 8—which benefits the ability of MDBs to ramp up counter-cyclical lending to help mitigate crisis impacts on developing borrower countries. As the 2015 G20 statement on MDBs noted, “AAA credit ratings have been at the core of the business model of many MDBs,” and any action to change to MDB operations is only viable if “AAA ratings would not be put at risk” (G20 2015).Footnote 9

This study only analyzes the rating methodology used by Standard and Poor’s (S&P) since 2012 in detail. Although numerous bond rating agencies exist, by far the most important players are the “Big Three” of S&P, Moody’s and Fitch, which jointly accounted for 96.6% of all bond ratings outstanding as of end-2013, and 99.1% of all government security bond ratings (SEC, 2014, p. 8). These three firms established themselves as the main providers of bond ratings over the decades since Moody’s first set up shop evaluating railroad bonds in the early 1900s (Sinclair 2005; Shorter and Seitzinger 2009, and Langohr and Langohr 2009). Other firms exist around the world,Footnote 10 and some are important in their domestic markets, but none have come close to threatening the dominance of the Big Three. According to MDB staff directly responsible for interacting with bond markets and CRAs,Footnote 11 they hold regular meetings and interact only with the Big Three CRAs.

Of the Big Three, S&P’s rating methodology is by far the most binding on MDB operations, as confirmed in every interview done for this paper. By employing a highly quantitative, formulaic methodology, S&P generates comparable ratings across asset classes (commercial banks, investment banks, MDBs, etc.), as demanded by regulators. As a result of this approach, however, S&P evaluates MDBs similarly to private financial institutions, despite the many unique characteristics of MDBs as cooperative development banks. The less proscriptive and more subjective approaches used by Moody’s and Fitch are not as problematic for MDBs, according to all interviewees. As such, S&P serves as an “extreme case” to highlight the issues of MDB dependence on capital markets.

The paper’s research methodology is designed to address two principal questions: i) do CRA methodologies impact the ability of MDBs to pursue their development mandate, and ii) if so, in which ways. The empirical sections of the paper examine S&P’s methodology in detail, using data from the annual reports and financial statements of the MDBs themselves as well as rating agency reports to highlight the specific ways in which the methodology impacts MDBs. This is supplemented with in-depth interviews with 13 officials (mainly from risk and treasury departments) from five different MDBs.Footnote 12 Three interviews were also conducted with CRA analysts.

4 MDB evaluation methodology

This section considers the conceptual underpinnings and internal logic of S&P’s methodology, with a particular attention on the need for S&P analysts to generate quantitative inputs to their ratings model.

4.1 Background to CRA assessment of MDBs and current context

The problems confronting MDBs from CRA methodologies is a relatively new phenomenon, or at least one not experienced in several decades. The World Bank had to work intensively to win over the New York capital markets after it was created in 1944, and did not receive its coveted AAA rating until 1959, after years of lobbying and very strong financial performance (Kapur et al. 1997 and Mason and Asher 1973). Once CRAs grew comfortable with the World Bank, however, the path proved much smoother for newer MDBs to receive AAA, which was granted almost immediately to the AsDB and IDB after their founding.

The main criterion of CRAs from the 1960s to the early 2000s was the backing of industrialized countries in the form of callable capital. Callable capital is a type of guarantee committed by MDB shareholders that can be called on in case of financial emergency. The callable capital of industrialized countries came to be viewed as an all-important security that allowed CRAs to grant AAA ratings.Footnote 13 The AfDB, for example, was created in 1964 with only the participation of African borrower countries, and was unable to access capital markets at useful financial terms until it accepted industrialized country shareholders and their callable capital (Strand 2001). Hence, the criteria of CRAs did not pose a problem to the operations of MDBs, from the point of view of major shareholder governments.

This comfortable situation continued until just a few years ago, according to interviews with MDB staff. In the wake of the global financial crisis of 2008, however, circumstances changed. As is well known, CRAs played a key role in the crisis by granting ratings to bonds—notably structured financial securities—that later proved highly risky. S&P was fined $1.5 billion in 2015 and Moody’s $864 million by U.S. authorities for their role in the 2008 crisis (Reuters 2015 and 2017), and all the CRAs have faced greater regulatory and legal pressure from United States Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), and others (CFR, 2015).

This sudden increase in external pressure and attention has led CRAs to revamp their methodologies for evaluating different classes of investments, including MDBs (see Kruck 2016). The focus has been to make rating criteria more easily comparable across different asset classes (corporates, banks, municipalities, sovereigns, etc.), as well as to make the methodologies more transparent. Fitch Ratings (2014) and S&P ( 2012) published updated and much more thorough methodologies for MDBs, while Moody’s Investor Service (2013) published their methodology for the first time.

Of the three, S&P moved much further toward developing a formulaic and replicable approach to evaluating MDBs compared to Moody’s or Fitch,Footnote 14 which according to MDB staff interviews as well as a direct comparison of the methodologies still employ considerably more qualitative judgments in arriving at their final rating. A former lead MDB analyst with S&P, who was involved with designing the new methodology, stated that “the previous way wasn’t really a methodology, if an MDB tried to apply it to themselves they would only have a vague idea where they would come out…The new approach is much more elaborate and highly mathematical.”

S&P built a complex mathematical methodology for evaluating private financial institutions in 2009, under tremendous pressure from the SEC, and subsequently adapted it to MDBs. However, MDBs differ fundamentally from private banks in a number of significant ways, including:

-

Mission: MDBs are not profit-oriented institutions, but rather seek to achieve development outcomes that do not appear on their balance sheets.

-

Ownership and balance sheet: MDBs are for the most part owned by shareholder governments, and the capital structure and balance sheet are very different from private banks.

-

Callable capital: A large majority (over 90% in most cases) of MDB total subscribed capital is in the form of callable capital, a type of guarantee that does not form part of MDB equity and is not used in private banks.

-

Loan concentration: The loan portfolio of most MDBs is structurally concentrated, with a very small number of borrowers compared to commercial banks.

-

Preferred credit treatment (PCT): Borrowers have generally (though informally) granted MDBs a privileged position to be first in line for repayment, should a government face financial restrictions.

-

Lack of regulator and LOLR: MDBs do not fall under banking regulations of any single government, making them essentially self-regulated. As well, apart from the single case of the European Investment Bank (EIB), no MDB has formal access to lender-of-last-resort facility in case of liquidity problems.

CRAs must find some way to take these unique aspects of MDBs into account in arriving at their bond rating. This is no simple task, as some aspects (such as PCT) are informal and others (like callable capital) have no easy analog in private financial institutions to use as benchmarks, and their impact on the ability of an MDB to repay bondholders is uncertain. In the face of this confusing panorama, and in the wake of severe criticism for their role in the global financial crisis, S&P adopted a highly conservative approach to quantifying several of these unique MDB characteristics and forcing them into a rating methodology originally designed for private banks.

One key aspect of this highly quantitative approach is the Risk Adjusted Capital Framework (RACF) used by S&P for all financial institutions since 2009 (Reuters 2009), and which has been adapted to MDBs. Because of its importance in understanding later sections of this paper, it is worth describing S&P’s RACF in general terms. The RAC ratio is a measure of capital adequacy, expressed as a percentage, and is created by dividing shareholder equity (paid-in capital plus reserves) by risk-weighted assets (mainly outstanding loans, weighted by how risky S&P considers each borrower). This RAC is then adjusted in several ways, as described later in the paper. The advantage of the RAC is, as S&P states in their methodology, that it “…introduces comparability with other financial institutions in that we use the RACF for commercial banks as well.”Footnote 15

The highest RAC category that can be aspired to by an MDB is above 23% (“extremely strong”)—the explicit target for every MDB official interviewed for this study, as it facilitates achieving a AAA rating. The major MDBs show adjusted RAC ratios of between 15 and 28% (Fig. 1), while most commercial financial institutions are below 10% (S&P 2013).Footnote 16

Although the RAC ratio forms only part of an MDB evaluation—generating the “financial profile,” which is then combined with the “business profile” to arrive at the stand-alone rating—it has assumed a much higher effective importance, for two reasons, according to interviews with MDB financial officials. First, it provides a shorthand for the capital adequacy of MDBs, which immediately attracts the attention of investors, whatever its formal weight in the rating methodology. Second, it is the variable most subject to large fluctuations year-to-year, depending on factors largely outside an MDB’s control (in particular the riskiness of borrower countries, as judged by S&P), and thus has an outsized marginal impact on an MDB’s rating changes.

The remainder of this section focuses on three aspects of S&P’s methodology that weigh particularly heavily on its assessment of MDBs:

-

Concentration risk inherent in MDB loan portfolios

-

Preferred creditor treatment granted by borrowers to MDBs

-

Callable capital committed by shareholders to MDBs

Other factors such as liquidity requirements, net income and reserve accumulation and an explicit bias in favor of non-borrower led MDBs,Footnote 17 among others, are also relevant but are not taken up here due to space limitations as well as the overwhelming attention paid to these three factors by MDB staff in interviews.

4.2 Portfolio concentration risk

MDBs lending mainly or entirely with government borrowersFootnote 18 have an inherently narrow loan portfolio, particularly the regional and sub-regional MDBs focused on a specific geographic area. The non-concessional lending windows of the major regional MDBs have between 15 (AfDB) and 32 (AsDB) country exposures, compared to thousands of individual exposures for most large commercial banks. And even in this small portfolio, the bulk of loans are to a small number of large middle-income countries, due mainly to their absorptive capacity—the top five countries represent 44% if the World Bank (IBRD) loan portfolio, and over 80% for AsDB (Fig. 2). All else being equal, a highly concentrated portfolio is inherently riskier than one distributed among many borrowers, and CRAs must take this into account in their assessments.

The approach used by S&P since 2012 to evaluate portfolio concentration has a major impact on MDB capital adequacy. After calculating the RAC as described above, S&P makes a series of adjustments to it. Of these, the adjustment for concentration—the “single-name concentration penalty”—is by far the largest. This penalty is assessed to an MDB’s RAC as a result of having a high share of their loan portfolio to a single borrower (“single name”), and is particularly severe when that borrower has a low S&P sovereign rating. The penalty is added to the value of risk-weighted assets (RAC denominator), meaning that the overall RAC percentage is lowered following this adjustment. After taking portfolio concentration into account with S&P’s technique, the regional MDBs in particular suddenly look seriously undercapitalized (Fig. 3).

The calculation used by S&P is highly problematic, and criticized by finance officials at all MDBs. S&P’s formula is based on a paper by two economists to refine Basel II capital adequacy evaluation for commercial banks, which penalizes large, risky individual exposures (Gordy and Lütkebohmert 2007). While the adjustment may be appropriate for commercial banks, the paper on which S&P’s formula is based clearly states that the methodology is designed for banks with at least 200–500 exposures, and that banks could expect adjustment ranges between 3 and 20% of total capital (Gordy and Lütkebohmert 2013). However, as applied by S&P to MDBs, the penalty increases the level of risk-weighted assets by more than 100% for both the IDB and AsDB (Fig. 4). That is, the adjustment makes it seem that these MDBs have loan portfolios more than twice as large as is actually the case—a huge penalty following the same lending patterns that they have had for decades.

Despite the impact of the concentration penalty on MDB RAC ratios, the caveats in the paper on which it was based, and vociferous complaints by MDB management, S&P has persisted with its use. Several MDB officials suggested that the reason for this is that there is simply no other available tool with sufficient credibility that they can use to generate inputs into their RAC ratio. Moody’s, which does not attempt to generate any ratio analogous to the RAC, uses standard measures of concentration like the share of the total portfolio accounted for by the top ten borrowers. The result, according to the Moody’s methodology itself (Moody’s Investor Service 2013, Exhibit 7 and p. 12) as well as the feedback of MDB officials, has a relatively minor impact on MDB rating and operations.

4.3 Preferred creditor treatment

Due to the official status and developmental nature of MDBs, countries have granted MDBs “preferred creditor treatment” (PCT). This means that borrower governments will continue to repay MDBs even if for some reason they may go into default or delayed repayment to other creditors. PCT has meant that MDBs have generally had much lower non-performing loan (NPL) records than commercial banks (Fig. 5). Even the AfDB, which has a substantially higher NPL ratios than the other major MDBs, is still below the average for US commercial banks. However, PCT is informal, with no binding legal or contractual status, and as a result is difficult for CRAs to account for in their ratings.

S&P calculates PCT with a formula to arrive at a number that can be included as an adjustment to the RAC ratio, similar to single-exposure risk. In this case, PCT enters as a bonus that increases the RAC (rather than a penalty that decreases it, as with single-exposure risk), in recognition of the fact that PCT allows an MDB to carry more loans based on the same equity capital, due to lower repayment risk. However, the weight given to PCT is quite low relative to the concentration penalty, resulting in only a small bonus for MDB capital adequacy. The bonus does not offset the concentration penalty, whereas the methodologies used by Moody’s and Fitch do, in recognition that they are two offsetting characteristics built into the MDB business model (Fig. 6).

Not only does S&P give little credit for PCT, but the way they arrive at a numeric value for PCT to plug into the RAC ratio is questionable. S&P employs a “multilateral debt ratio”, which considers how much of a country’s external debt is to multilateral creditors. The higher this ratio, the lower the PCT bonus S&P credits to an MDB. At the high extreme of 100% multilateral debt, this is intuitively logical—if all of a country’s debt is to multilaterals, then preferred creditor status has little or no value. However, the rationale for using the ratio is much less clear below 100%, and S&P does not explain in its methodology why it considers this to be the best approach (S&P 2012, p. 29).

The relationship between S&P’s multilateral debt ratio and PCT is not borne out by the historical record. IDB staff undertook a detailed study of all default events by borrower governments to commercial lenders in the previous 50 years.Footnote 19 Of the 63 such cases, only seven had payment delays of longer than 180 days to the IDB—itself an impressive statement of PCT. But further, the IDB calculated the multilateral debt ratio for all 63 cases, and found that the ratio did not correlate to IDB repayment in the way predicted by S&P, and in fact tended in the other direction (lower ratio countries were more likely to delay repayment to the IDB, rather than higher ratio countries). Staff at the World Bank and AfDB reported similar results in their own track record.

Beyond the conceptual problems with how the multilateral debt ratio is calculated, S&P also misrepresents payment delays at MDBs by implicitly treating them the same as at commercial banks. On the rare occasions that MDB borrowers delay repayment on sovereign loans, they invariably repay both principal and interest—unlike commercial banks where borrowers frequently never pay the loan back at all. MDBs never write off loans,Footnote 20 and as a result the notions of sovereign “default” and subsequent “loss given default” are not applicable in a meaningful way to MDBs. Sovereign borrowers remain shareholders of MDBs even while not repaying their loans, and have always eventually become current again to continue accessing MDB services. Hence, while MDBs do face periods of lost net income during non-repayment events, they are fundamentally different than with a commercial bank, which face very substantial losses from defaults.

In sum, S&P’s methodology seriously underestimates the strength of PCT and applies a concept of loss given default that has never historically held true for MDBs. “There’s very low defaults in multilateral sector, and even in default in the end they pay,” said one MDB treasury staffer. “They [S&P] say they make adjustments, but when you see the calculations they are certainly not sufficient.” Sovereign borrowers view MDBs not simply as banks, but rather cooperative international institutions that they are part owners of, and which provide them with financing, knowledge and a voice in the international arena that cannot be replicated elsewhere. Hence, a decision to stop payment on an MDB loan is more than a mere financial decision, and as the historical record has shown, countries that do stop payment invariably repay principal and interest in the end.

4.4 Callable capital

As with PCT, callable capital is a unique aspect of MDBs that cannot easily be compared to commercial financial institutions, and is hence difficult for CRAs to evaluate. Callable capital is a type of “reserve” capital promised by governments should an MDB be unable to pay off bondholders due to financial crises. It accounts for the vast majority of total shareholder capital at most MDBs (Fig. 7).

Calculating exactly how callable capital should be valued in financial terms is not a simple task. It is an obligation by shareholder countries via international treaty as part of their membership to an MDB, but it is not a guarantee that can be called by the MDB under clearly defined circumstances, as with other types of financial guarantees. Instead, those who would pay the guarantee—MDB shareholders—are the same ones who would have to declare a call. The process of doing so varies in different MDBs, and has never been tested as no MDB has ever made a capital call. Nor have member governments allocated the necessary funds out of their budgets, meaning some type of legislative approval would be required in most cases.

As a result, CRAs have no clear roadmap or historical record to guide them on how to incorporate callable capital into their evaluation methodologies. Both S&P and Moody’s do so as a final adjustment to their MDB rating, added on after all other factors have been summed up into a provisional “stand-alone” (S&P) or “intrinsic” (Moody’s) rating.Footnote 21 However, S&P takes a much more stringent view on how much credit to give callable capital than Moody’s. In practice, S&P only credits callable capital from governments that are themselves rated AAA for the World Bank and major regional MDBs (S&P 2012, p. 26). As a result, huge sums of callable capital—including that of the United States (rated AA+ currently by S&P) are effectively ignored in the determination of the financial strength assessment of the major MDBs (Fig. 8). To give one example, of the IDB’s nearly $107.6 billion in callable capital from countries rated above investment grade, S&P factors only $11 billion into their rating.

While it is reasonable to not give full credit for all callable capital equally, the probability of industrialized nations like the U.S. (AA+), the Netherlands (AA+), France (AA) or Japan (A+)—not to mention emerging global powers like China (AA-)—of meeting their international obligations in times of crisis is certainly greater than zero. Sub-AAA callable capital has been radically devalued in S&P’s new methodology, to the point that MDBs are suddenly engaging in, as one official put it, “soul searching as regards the quality and value of callable capital.” Another said, “We agree it [sub-AAA callable capital] shouldn’t have same value as AAA, but we think that it should have some value. And they give zero credit for it.” S&P’s methodology is effectively declaring tens of billions of dollars in international obligations in an instrument designed more than seven decades ago to promote global development to be essentially worthless.

One reason why S&P uses this highly restrictive approach to accounting for callable capital is that it actually attempts to incorporate it into the RAC ratio as a final step in its rating process. That is, when an MDB’s “stand-alone” rating is completed, S&P will increase an MDB’s rating up to three notches based on its callable capital. For example, the IDB’s adjusted RAC at end-2013 was 17% (equity of $23.4 billion/risk-weighted assets of $140.1 billion). By including 2013 AAA-rated callable capital of $9.9 billion, equity increased to $33.3 billion, and the RAC with shareholder support became 24%—just above the threshold needed to achieve a AAA rating.

This works out in a relatively proportionate way in the case of the IDB, but leads to some other MDBs appearing tremendously well capitalized (Table 2). The IBRD, for example, receives no uplift from callable capital, as it is rated AAA on a stand-alone basis and had a stand-alone RAC of 28% in 2013. But if one were to include the IBRD’s $40 billion in AAA callable capital into shareholder equity, its RAC would increase to 56%—more than double the 23% level needed to achieve the highest RAC category attainable for an MDB.

As a hypothetical exercise,Footnote 22 adding AAA callable capital in equity suggests that the IBRD could add $400 billion to its loan portfolio (US$157 billion as of 2015) under the same risk profile as currently, and still have a RAC of 25% (Table 2). Asking if the potential loan portfolio increases in Table 2 were realistic elicited amusement from MDB financial staff. “No chance,” said one flatly. “These numbers aren’t real, they’re just S&P’s way of looking sophisticated so they can give AAA ratings to the big MDBs.” The numbers highlight the conceptual confusion on S&P’s part on how to cope with callable capital within their quantitative RAC framework.

5 Do credit rating agencies influence MDB development operations?

While the previous section critiqued the conceptual basis and internal logic of S&P’s MDB methodology, this section provides evidence on how the methodology has actually impacted MDB operations in practice. One might presume that, since none of the four MDBs considered here have experienced a downgrade as a result of S&P’s new methodology, that it is simply an elaborate facade used by S&P to placate regulators, but with no real influence on MDB activity.

In fact, officials from all four MDBs analyzed hereFootnote 23 confirmed that the impact of the new methodology has been very substantial, forcing MDBs to modify daily decisions on individual lending operations in the interests of maintaining their all-important AAA rating. The application of S&P’s new methodology resulted in the three major regional MDBs (especially the AfDB and IDB) appearing to be right on the edge of being downgraded. As a result, the impact that each loan operation might have on MDB ratings has quickly become an integral part of MDB decision-making processes, along with more traditional criteria such as need, development impact and implementation capacity. “S&P has become the de facto regulator for us,” one MDB official said. “Everything we do, we test immediately to see how it will impact the rating.”

A treasury staffer in one MDB said that they assume if their RAC drops to 13% or so, they might be downgraded—although they can’t be totally sure and thus need to factor in a buffer. Each proposed new operation is tested to see how it will impact the RAC, and in some cases developmentally strong projects will be turned down due to these financial considerations. “We calculate that for each loan in each country, and determine how much additional lending would help or hurt our RAC,” the staffer said. The RAC formula is also now the key driver for deciding overall country lending envelopes, which the staffer said are recalculated each quarter to ensure no threat to the RAC.

In one case, a treasury official described a lower-middle income country that was “graduating” out of the concessional lending to the concessional lending window. “There was a lot of reluctance to lend on the part of treasury, because this is a riskier country,” the staffer said. “We did the calculations and found that the diversification impact [i.e. reducing the concentration penalty] far outweighed the single country risk, so we went ahead. But if it hadn’t, we might not have been able to open up lending,” thus leaving the country without access to either concessional or non-concessional lending.

These new considerations have been baffling for operations staff accustomed to focusing mainly on developmental criteria. A vice-president of operations at one of the major MDBs voiced frustration with how S&P’s evaluation had become central to operational discussions. “You cannot overstate the impact that this methodology has had on our operations—it has in a way changed our entire business model. Formerly we assigned our resources strictly based on need and absorption capacity. But bit by bit the S&P methodology has become the main driver of our allocation decisions…I can’t simply push resources on smaller economies to improve our portfolio, they can’t absorb it. And at the same time I have huge demands from countries that I cannot serve because of the impact on our capital ratio. It [S&P’s methodology] has become a major constraint, if not the major constraint.”

The factor having the most direct impact on MDB operations is how S&P calculates the risks posed by loan portfolio concentration, according to all MDB staff interviewed. The nature of MDBs indicates that they should undertake lending operations in cycle-neutral or at times counter-cyclical fashion—that is, lend more during difficult economic times—but should not act pro-cyclically in a way that would accentuate economic swings. However, the concentration penalty encourages pro-cyclicality. The S&P methodology has built-in incentives for MDBs to reduce lending during times of crisis, and to expand lending to countries that are performing strong economically—exactly the opposite of what an MDB should be doing in pursuit of its development mandate—in an effort to maintain a AAA bond rating.

The concentration penalty has been a major problem since the introduction of S&P’s new methodology for the AfDB and IDB in particular. The AfDB severely restricted lending to two major borrower countries badly in need of support during a time of traumatic political and economic turmoil, Egypt and Tunisia. Egypt—by far the largest borrower from the AfDB between 2005 and 2010, averaging over US$500 million in approvals annually—was suddenly cut off in the wake of the Arab Spring, with no loans granted between 2012 and 2014, despite the urgent need of Egypt for financing. As one AfDB official said, “The North African countries were most efficient at using our resources, and had a big portfolio. Then they got downgraded and we had to back off, arguably when they needed us the most…The Egyptians were very upset.”

The IDB has faced a similar situation due to Argentina, which was rated as “selective default” by S&P since 2001—the lowest possible rating—and represented 16.5% of IDB’s portfolio in 2013. This combination of low rating and high share of the portfolio translated into a very high concentration penalty in S&P’s methodology. According to the Argentine executive director, this led to “some pretty drastic cuts to our envelope in the last two years, due to the impact that more loans would have had in S&P’s methodology.”Footnote 24 After the RAC methodology became operational in 2013, IDB lending to Argentina dropped from an average of US$1.3 billion annually in 2010–2012 to US$660 million in 2014 and US$750 million in 2015.

Beyond the difficulties S&P’s RAC creates lending to individual countries, it also impacts the aggregate size of MDB loan portfolios as a ratio to their equity capital. The very high loan portfolio concentration penalty combined with the limited recognition of PCT mean that MDBs now “consume” their equity capital at a much faster rate than prior to the introduction of the S&P methodology, meaning their headroom to expand lending is much reduced.

MDBs have engaged in creative financial engineering to address the impacts of the new S&P methodology on their capital adequacy. In lieu of a new round of capital increases—which are politically difficult and time-consuming—MDBs have been piloting new options to clear space off the balance sheet. This has included a synthetic exchange of a portion of loan portfolios between the AfDB, IDB and World Bank, with the express purpose of reducing S&P’s concentration penalty charged against the first two (AfDB 2015, p. 112). While successful, MDB staffers in the involved banks expressed some trepidation that they were engaged in such complex financial engineering “to circumvent the shortcoming of one rating agency,” said one. “If the methodology changes, the benefits of the operation might also completely change.”

Although not on the same magnitude as the impact on lending, it is also worth noting how S&P’s methodology is consuming MDB staff time. All MDBs consulted have entire teams dedicated to reverse-engineering the methodology and calculating operational impacts on the RAC on an ongoing basis. The concern on the rating has permeated through different levels of management and up to the board level. This was confirmed during two separate workshops with executive directors of the IDBFootnote 25 and World Bank,Footnote 26 during which numerous executive directors noted the sudden increase in references to S&P’s methodology when making decisions on lending operations and financial management. While financial concerns have always been present in MDBs, they have taken on a heightened importance and represent a substantial cost of time and energy that could be spent focusing on the MDB’s developmental mandate. Should the other CRAs move in the direction of S&P’s quantitative RAC approach (which several MDB staffers expressed nervousness about), this situation could worsen.Footnote 27

6 Conclusions

This study has examined the influence that the unique financing model of multilateral development banks (MDBs) has in shaping their ability to pursue their development mandate. The fact that MDBs raise a major share of their operating resources on international capital markets rather than from regular direct contributions from government shareholders has been a key reason why this particularly type of international organization has proliferated. However, it also means that government shareholder “principals” do not entirely control MDB finances, as they do in IOs directly supplied with budgetary allocations. Bond buyers and, by extension, credit rating agencies (CRAs) also have a major say in how MDBs are run—and they have no particular interest in the development goals that MDBs are pursuing on behalf of member governments.

Previous research has shown how the need for MDBs to ingratiate themselves with capital market players shaped lending policies and even membership of major MDBs in their early years (Kapur et al. 1997 and Humphrey 2016). The present study has analyzed the current situation, and found that the methodologies used by the major credit rating agencies (CRAs)—in particularly Standard & Poor’s (S&P)—are having a substantial negative impact on the ability of MDBs to undertake their development mission. By analyzing MDBs in a manner too similar to commercial banks, CRAs are fundamentally mis-characterizing what MDBs are designed to do and underestimating their unique financial strengths.

MDBs have always faced statutory and policy limitations on the expansion of their balance sheets, due to investor perceptions and, in many cases, a strong desire by some non-borrower shareholders to protect callable capital (Humphrey 2014). However, the revised CRA methodologies implemented after 2012 have restricted MDBs even further. The new methodologies embed strong incentives for MDBs to protect their AAA bond rating by i) acting even more conservatively than previously in utilizing their capital for development and ii) restricting lending to individual countries facing difficulties—both of which conflict with their mandate. These impacts have been particularly strong for regional MDBs.

The fact that CRA methodology is able to have such a major impact on the operations of the world’s most important development organizations is a testament to the importance of how the need for external resources shapes organizational behavior. Governments are happy to be relieved of budgetary pressure to fund development projects by MDBs’ ability to tap capital markets for resources. But the trade off is that governments lose some of their control to private market players like S&P, who have no responsibility to uphold MDBs’ developmental mandate.

These findings add to our understanding of what makes MDBs tick. Major shareholder governments have a significant role in shaping MDB policy and actions, as a substantial body of research has shown. Bureaucratic incentives, organizational culture and evolving development ideology also play a role. However, a deeper awareness and understanding of their financial model is essential to obtain a more complete view of the factors explaining MDB activities. In the language of the principal-agent framework, capital market financing is an intervening variable that limits the control government principals are able to exercise over MDB agents by i) reducing the principals’ “power of the purse” over MDBs and ii) incentivizing MDB staff to cater to the views of a set of actors uninterested in the development mandate for which they were created.

The empirical issues examined in this paper—the details of the new S&P methodology—represent only one aspect of how capital markets and financial pressures shape MDB behavior. Considerably more research could be undertaken in this direction. In relation to CRAs, one could in the coming years (after sufficient time has passed) use a data-driven approach to see how lending patterns may have changed overall and in relation to specific countries in the wake of the introduction of new CRA methodologies.Footnote 28 As well, one could attempt to reverse-engineer S&P’s methodology and apply it to previous years, to see what ratings would result.

More broadly, it would be fascinating to track bond yields over the years for different MDBs and test for correlations with either political or economic events, thus getting more directly at how capital markets perceive MDBs. A detailed study of how non-AAA rated MDBs interface with capital markets and CRAs would also be worthwhile, to get a sense of how varying development mandates, geographic specializations and governance/ownership arrangements impact MDB financial potential. Similar work could further be undertaken in relation to national development banks, many of which fund themselves at least in part by issuing debt on capital markets.Footnote 29

Although this paper did not reflect directly on the motivations of CRAs, the findings are a curious case to fit into the growing body of IPE literature on the role of CRAs. Existing research has focused largely on why CRAs over-rate assets (such as asset-backed securities in the run-up to the 2008 crisis), but in this case they are under-rating a certain asset class. A closer look at this case might help shed light on the validity of existing theoretical understanding of CRA behavior. In particular, digging deeper into why S&P chose to move ahead with such a highly quantitative and restrictive methodology for MDBs, while Moody’s and Fitch have not, could potentially be revealing of incentives faced by CRAs and their relations to governments and regulators.

The paper’s findings have substantial policy relevance. Calls for MDBs to ramp up their lending to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals make for good summit declarations (G20 2015). However, these lofty goals may run up against a less forgiving reality in the capital markets, which would be the main suppliers of resources if there is any hope of actually moving from “billions to trillions”. Assuming that governments are not going to pay these trillions, then bond investors and CRAs will have a say in the matter. Major shareholder governments could take policy action against CRAs, as they are likely to have influence both formal (through the authority delegated to CRAs as “agents” to smooth the functioning of capital markets) and informal (through economic and political clout). One would expect the industrialized shareholders would have an incentive to do so, since their capital is not being put to the most effective use in MDB operations, in part because of CRA methodology.

These tensions between development goals and the need to fund in capital markets are likely to become even more important going forward, as donor aid budgets to support MDB lending to the poorest countries decline. For example, the AsDB is now folding its concessional window for the poorest countries into its market-based non-concessional window, for the explicit purpose of leveraging greater resources via capital markets than would be possible just through donations (AsDB, 2014). The September 2016 initial credit rating of the World Bank’s IDA indicates that it, too, is likely to tap capital markets in the near future (Standard and Poor’s 2016).

The basic underlying model of MDBs remains as relevant now as when the World Bank was first created in 1944, as the recently created Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and New Development Bank attest. This highly successful form of international organization is clearly here to stay, and an accurate understanding its financial model and dependence on capital markets—in both academia and the policy world—is essential to fully appreciate the incentives and pressures that drive MDB behavior.

Notes

See World Bank 2016, pp. 17 and 28 for a description of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) funding program.

Similarly, MDBs must be responsive to demands of borrower countries to ensure continued lending, which also can lead to conflict with shareholder governments.

Anonymous World Bank executive director interview, 25 January 2011. World Bank executive directors are the representatives of member countries, who vote to decide most lending and policy decisions.

In one telling historical anecdote on the power of independent financing, a top World Bank staffer relates a discussion from the 1950s where UN officials were unsuccessfully pushing the Bank to follow UN guidance. “They [the UN] are the central global body, and they feel they ought to be able to exercise authority over all the other international agencies. On the other hand, the Bank has the money” (cited in Humphrey 2016, p. 97).

This paper does not address the ability of sub-AAA MDBs to access capital markets and the impact of this on their operations, but it would be a worthwhile topic for further research.

A World Bank Treasury staffer said in an interview in 2009, referring to the global financial crisis: “For the AAA MDBs like the World Bank and IADB, we had tons of ways to get funding because of the flight to quality. In any kind of market crisis investors don’t want to take risks, they go straight for a safe havens like the AAA supranationals, and in particular the World Bank.”

Other advantages of AAA include facilitating private bond placements with major institutional investors, especially central banks, and reduced liquidity needs due to the lack of need to back up derivative exposures.

The Japan Credit Rating Agency was the only CRA outside of the Big Three with a published methodology for evaluating MDBs. See Japan Credit Rating Agency 2013.

See reference section for interview list.

See reference section for interview list.

As the former director of the World Bank’s Finance Area wrote in 1995: “…ratings agencies do not actually base their rating of the MDBs on the spurious sophisticated and often confusing, if not almost irrelevant, financial ratio analysis they purport to impress their readership with. Instead, they now appear to be basing their judgment solely on the strength of usable callable capital.” Mistry 1995, p. 17.

Considering why S&P moved the farthest in this direction is beyond the scope of this paper, but is likely due to a combination of business strategy, internal corporate culture and possibly greater pressure and attention due to S&P’s leading position in the rating industry (46% of outstanding bond ratings as of Dec. 31, 2013).

Of the top 100 rated banks in 2013 (highest rating AA-, three steps below AAA), only four had ratios above 10%: Norinchukin Bank (Japan) 11.2%; Caisse Centrale Desjardins (Canada) 10.9%; Shinkin Central Bank (Japan) 10.1% and National Commercial Bank (Saudi Arabia) 11.3%.

More than a dozen other MDBs exist, most of which have a substantial and often majority shareholding by borrowers. These MDBs are strongly and negatively impacted by this bias in favor of non-borrower led MDBs. For more on sub-regional MDBs, see among others Zappile (2016).

Portfolio concentration is much less problematic for MDBs with mainly private sector borrowers, such as EBRD and IFC, as they have many more individual borrowers.

Interviews with IDB treasury staff.

MDBs have participated in debt relief initiatives like Highly Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) and Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI), but this is not technically considered a loan write off.

Unlike Moody’s S&P publishes its “stand-alone” rating before accounting for callable capital. This is a point of contention with some MDBs, as they feel it could lead investors to penalize MDBs with sub-AAA stand-alone ratings (like IDB and AfDB currently), even though their final issuer rating is AAA.

Not considering statutory limits, loan demand and absorptive capacity among borrowers, administrative capacity at MDBs, or capital market resource raising requirements to fund loans, among others.

As well as from the Andean Development Corporation (CAF) and European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD).

Andrea Molinari, IDB executive director for Argentina, 10 June 2015.

Annual retreat of IDB Executive Board, Washington D.C., 30 July 2015.

Workshop on credit rating agencies and MDBs organized by G24 for World Bank executive directors, Washington D.C., 31 July 2015.

As one treasury staffer put it, “The other agencies [CRAs] are looking over their shoulders and saying, “why is S&P getting all this attention?” So soon they will come up with their own models. If the other agencies have models that are different, then we’ve got to deal with three or four models, each one with different criteria and giving different results.”

Even with more time and data, such an analysis would be difficult because it is not possible to determine the criteria used by an MDB to decide each country’s lending envelope in a given year. Hence a country’s allocation may have declined or risen, but it would not be immediately clear through quantitative analysis if this was due to a CRA methodology issue or some other factor (political considerations, development need, absorptive capacity, etc.).

For example, China Development Bank—the largest development bank in the world, with US$1.5 trillion in assets at end-2015—gets about 75% of its resources from bond issues (CDB, 2016).

References

African Development Bank. (1966-2015). Financial Statement. Abidjan: AfDB.

Asian Development Bank. (1966-2015). Financial Statement. Manila: ADB.

Asian Development Bank. (2014). Enhancing ADB’s financial capacity to achieve the long-term strategic vision for the ADF. February 2014. Manila: ADB.

Babb, S. (2009). Behind the development banks: Washington politics, world poverty, and the wealth of nations. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Barnett, M., & Coleman, L. (2005). Designing police: Interpol and the study of change in international organizations. International Studies Quarterly, 49, 593–619.

Barnett, M., & Finnemore, M. (2004). Rules for the world: International organizations in global politics. Cornell University Press.

Bolton, P., Freixas, X., & Shapiro, J. (2012). The credit rating game. The Journal of Finance, 68(1), 85–111.

China Development Bank. (2016). Annual report and financial statement. Beijing: CDB.

Choi, S., & Hwang, L. (2012). Do rating agencies fully understand information in earnings and its components? Working paper: Lancaster University Management School and Seoul National University.

Council on Foreign Relations. (2015). The credit rating controversy. In CFR backgrounders, updated 19 February 2015. Washington D.C.: CFR.

Federal Reserve of St. Louis. Federal Reserve Economic Data. Online database, accessed at https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/.

Fitch Ratings. (2014). Supranationals rating criteria. May 22, 2014. New York: Fitch.

G20. (2015). Multilateral Development Banks Action Plan to Optimize Balance Sheets. Communique, Nov. 15–16, 2015. Antalya: G20.

Gordy, M., & Lütkebohmert, E. (2007). Granularity adjustment for Basel II. In Discussion paper series 2: Banking and financial studies, 01/2007. Frankfurt: Deutsche Bundesbank.

Gordy, M., & Lütkebohmert, E. (2013). Granularity adjustment for regulatory capital assessment. International Journal of Central Banking, 9(3), 33–71.

Gould, E. (2006). Money talks: The International Monetary Fund, conditionality, and supplementary financiers. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

Hawkins, D., D. Lake, D. Nielson, & M. Tierney, M. 2006. Delegation and agency in international organizations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Humphrey, C. (2014). The politics of loan pricing in multilateral development banks. Review of International Political Economy, 21(3), 611–639.

Humphrey, C. (2016). The invisible hand: Financial pressures and organizational convergence in multilateral development banks. Journal of Development Studies, 52(1), 92–112.

Inter-American Development Bank. (1960–2015). Financial Statements. Washington D.C.: IDB.

Japan Credit Rating Agency. (2013). Rating methodology: Multilateral development banks. March 29, 2013. Tokyo: JCR.

Kapur, D. (2000). Processes of change in international organizations. In Working paper 00–02, Weatherhead Center for International Affairs. Harvard: University.

Kapur, D., Lewis, J. P., & Webb, R. (1997). The World Bank: Its first half-century (Vol. 1). Washington DC: The Brookings Institution.

Kruck, A. (2016). Resilient blunderers: Credit rating fiascos and rating agencies’ institutionalized status as private authorities. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(5), 753–770.

Lake, D. (2007). Delegating divisible sovereignty: Sweeping a conceptual minefield. Review of International Organizations, 2, 219–237.

Langohr, H., & Langohr, P. (2009). The rating agencies and their credit ratings. Hoboken: Wiley.

Lyne, M., Nielson, D., & Tierney, M. (2009). Controlling coalitions: Social lending at the multilateral development banks. Review of International Organizations, 4(4), 407–433.

Mason, E., & Asher, R. (1973). The World Bank since Bretton woods. Washington DC: The Brookings Institution.

Mathis, J., McAndrews, J., & Rochet, J. (2009). Rating the raters: Are reputational concerns powerful enough to discipline credit rating agencies? Journal of Monetary Economics, 56, 657–674.

Mistry, P. (1995). Multilateral development banks: An assessment of their financial structures, policies and practices. The Hague: FONAD.

Mohammed, A. (2004). Who Pays for the World Bank? G-24 Research Papers. Retrieved 10 August 2016 from http://www.g24.org/TGM/008gva04.pdf

Moody’s Investor Service. (2013). Rating methodology: Multinational development banks and other supranational entities. December 16, 2013. New York: Moody’s.

Nielson, D., & Tierney, M. (2003). Delegation to international organizations: Agency theory and World Bank environmental reform. International Organization, 57, 241–276.

Nielson, D., Tierney, M., & Weaver, C. (2006). Bridging the rationalist-constructivist divide: Re-engineering the culture of the World Bank. Journal of International Relations and Development, 9(2), 107–139.

Niskanen, W. (1971). Bureaucracy and representative government. Chicago: Aldine.

Pfeffer, J., & Salancik, G. R. (1978). The external control of organizations: A resource dependence perspective. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

Reuters. (2009). S&P launches new bank capital ratio to weigh risk. 21 April 2009. Accessed at http://www.reuters.com/article/2009/04/21/financial-banks-sp-idUSLL62727020090421 on 15 August 2015.

Reuters. (2015). S&P reaches $1.5 billion deal with U.S., states of crisis-era ratings. 3 February 2015, by Aruna Viswanatha and Karen Freifeld.

Reuters. (2017). Moody’s pays $864 million to U.S., states over pre-crisis ratings. 13 January 2017, by Karen Freifeld.

Securities and Exchange Commission. (2014). Annual report on nationally recognized statistical rating organizations. December 2014. Washington D.C.: SEC.

Shorter, G., & Seitzinger, M. (2009). Credit rating agencies and their regulation. In CRS report for congress, 3 September 2009. Washington D.C.: Congressional Research Service.

Sinclair, T. (2005). The new masters of capital: American bond rating agencies and the politics of creditworthiness. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

Standard and Poor’s. (2010). Bank capital methodology and assumptions: Rating methodology and assumptions. 6 December 2010. New York: McGraw Hill.

Standard and Poor’s. (2012). Supranationals special edition 2012. New York: McGraw Hill.

Standard and Poor’s. (2013). Top 100 rated banks: S&P Capital Ratios and rating implications. 18 February 2013. New York: McGraw Hill.

Standard and Poor’s. (2014). Supranationals special edition 2014. New York: McGraw Hill.

Standard and Poor’s. (2016). International development association assigned ‘AAA/A-1 +’ ratings; outlook stable. 21 September 2016. New York: McGraw Hill.

Strand, J. (2001). Institutional design and power relations in the African development Bank. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 36(2), 203–223.

Vaubel, R. (2006). Principal-agent problems in international organizations. Review of International Organizations, 1, 125–138.

Weaver, C. (2008). Hypocrisy trap: The World Bank and the poverty of reform. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Woods, N. (2006). The globalizers: The IMF, the World Bank, and their borrowers. Ithaca: Cornell.

World Bank. (1945–2016). IBRD/IDA Financial Statements. Washington DC: World Bank.

Zappile, T. (2016). Sub-regional Development Banks: Development as Usual. In S. Park & J. R. Strand (Eds.), (pp. 187–211) Global Economic Governance and the Development Practices of the Multilateral Development Banks. London and New York: Routledge.

Interviews

Rating Agencies

Anonymous former lead MDB analyst, one of Big Three CRAs, 1 June 2015

Élie Heriard Dubriel, Senior Director, Sovereigns, Standard and Poor’s, 1 July 2015

Steven Hess, Moody’s, senior vice president, sovereign risk group, 23 June 2015

MDBs

AfDB

Riadh Belhaj, Credit risk group, 24 June 2015

Trevor de Kock, Treasury, 26 June 2015

Tim Turner, Chief risk officer, 12 June 2015

AsDB

Toby Hoschaka, Head of policy, Treasury, 25 June 2015

Michael Kjellin, Head of policy group, Office of Risk Management, 25 June 2015

Mitsuhiro Yamawaki, Director, Office of Risk Management, 25 June 2015

CAF

Gabriel Felpeto, Director of financial policy and international bond issues, 18 June 2015

Antonio Recine, Senior Specialist, Financial policy department, 18 June 2015

EBRD

David Brooks, Deputy Director, Financial Strategy and Business Planning, 13 June 2015

Isabelle Laurent, Deputy treasurer and head of funding, 13 June 2015

IDB

Gustavo de Rosa, Chief financial officer, 17 June 2015

Frank Sperling, Unit Chief, Strategic risk management, 25 June 2015

World Bank

George Richardson, World Bank head of capital markets, 23 January 2009

Lakshmi Shyam-Sunder, Vice President and Group Chief Risk Officer, 23 June 2015

Other

Anonymous Executive Director, World Bank, 25 January 2011

Andrea Molinari, IDB executive director for Argentina, 10 June 2015

Senior operations official, major regional MDB, anonymity requested, 11 September 2015

Acknowledgments

The empirical portion of this paper is a modified version of a working paper written for the Intergovernmental Group of Twenty-Four on International Monetary Affairs and Development (G-24). The author would like to thank Kai Gehring, Erica Gould, Christopher Kilby, Andreas Kruck, Helen Milner, Theresa Squatrito, three anonymous reviewers and the editors of this special issue of the Review of International Organizations for their feedback on earlier versions of this paper. The author is solely responsible for all errors and omissions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Humphrey, C. He who pays the piper calls the tune: Credit rating agencies and multilateral development banks. Rev Int Organ 12, 281–306 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-017-9271-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-017-9271-6