Abstract

How does state obligation to international human rights treaties (HRTs) affect mobilized dissent? We argue that obligations to protect human rights affect not only state behavior but also the behavior of dissidents. We present a theory in which the effect of HRTs on dissent is conditional on expectations of when it will constrain government behavior. We assume that HRT obligation increases the likelihood that government agents face litigation costs for repression but argue that leaders are only constrained when they would be most likely to repress. The expectation of constraint creates opportunity: citizens are more likely to dissent in HRT-obligated states with secure leaders and weak domestic courts. We find empirical support for the implications of our theory using country-month data on HRT obligation and dissent events from 1990 to 2004.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

How does state obligation to an international human rights treaty (HRT) affect mobilized dissent? Although numerous studies point to the social causes and societal consequences of mobilization and protest (see, e.g., Olson 1965; McCarthy and Zald 1977; Tilly 1978; Kuran 1991; Tarrow 1991; McAdam 1999; Gates 2002; Schussman and Soule 2005), very few scholars look to the effect of international institutions on these domestic outcomes. Those that do focus on how HRTs affect mobilization—and not dissent (Keck and Sikkink 1998; Risse et al. 1999; Dai 2005; Simmons 2009; Bell et al. 2014).Footnote 1 In the specific case of international treaties, scholars argue they coordinate disorganized actors, enabling and encouraging citizens to mobilize for the purpose of dissent. Formal obligations like HRTs serve as focal points, creating common goals around which individuals can rally (Weingast 1997; Keck and Sikkink 1998; Carey 2000; Dai 2005). Furthermore, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) often refer to international obligations when mobilizing collective demands, drawing on the law to convince actors of the importance of an issue and the state’s obligation to respond (Keck and Sikkink 1998; Risse et al. 1999; Hafner-Burton and Tsutsui 2005). These studies suggest that government obligation to HRTs may lower individuals’ expected costs of solving the collective action problem but say little about the connection between mobilization and actual dissent. Do international treaties affect the likelihood that groups challenge the state?

A group’s choice to challenge the status quo must balance the desire to change policies against an increased risk of repression. Repression is used to deter or end dissent (Tilly 1978; Earl et al. 2003; Davenport 2007a; Ritter 2014); citizens may be more likely to dissent when repressed (Almeida 2003; Cederman et al. 2010), or they may stay home altogether in expectation of repression (Rejali 2007; Sullivan 2015; Ritter and Conrad 2016). Institutions that affect authorities’ decisions to violate rights influence the government’s strategic interaction with dissidents, yet the growing body of work investigating the effects of HRTs focuses squarely on their influence on state repression as the dependent variable of interest (e.g., Hathaway 2002; Hafner-Burton 2005; Hill 2010; Lupu 2013b). Treaties have been connected to meaningful improvements in human rights protections in some cases (Hathaway 2007; Hill 2010; Lupu 2013b, 2015; Fariss 2014) but no effect or even worsening repression in others (Hathaway 2002; Hafner-Burton 2005; Hafner-Burton and Tsutsui 2007; Vreeland 2008). Even when authorities face meaningful institutional costs for rights violations, incentives to respond to dissent can lead authorities to repress anyway (e.g., Davenport 2007b; Conrad and Moore 2010; Conrad and Ritter 2013). In short, treaty obligations may contribute to mobilization, but they also have variable effects on government repression. Both of these treaty effects—on mobilization and on repression—influence the likelihood of dissent. How do citizens choose between these incentives? What effect does state obligation to a human rights treaty have on mobilized dissent?

We contribute to the scholarly understanding of the domestic consequences of international law by examining the conditions under which the expected effects of HRTs on government repression influence populations considering dissent. We argue that a treaty will modify a group’s decision to dissent based on their expectations of two factors: (1) the likelihood that a treaty will create consequences that a repressive actor would otherwise not incur and (2) the propensity of government authorities to repress. We assume that HRT obligation increases the likelihood that authorities will incur litigation costs should they repress—more actors will be willing to bring claims against the government. However, citizens will only expect this change to affect authorities’ behavior when extant, domestic institutions would fail to constrain rights violations in the absence of the treaty obligation. If authorities are already relatively constrained, the addition of small consequences will not alter their behavior. When authorities do not generally expect to come before the domestic court for repression, HRT obligation represents a meaningful change in the likelihood that repressive agents will face litigation costs. But leaders are only constrained by an institution when they are already inclined to repress, which we argue is correlated with the expected likelihood that a loss to the group would affect the leader’s likelihood of holding on to power (Conrad and Ritter 2013). If leaders would not repress the opposition regardless of their behavior, then an institution changes neither the expectation of repression nor dissidents’ behavior. Dissatisfied citizens expect treaty obligations to have the strongest constraining effects on repression when leaders face few domestic institutional constraints and are sufficiently secure to repress at will; these are the conditions under which treaties lead to more dissent.

We estimate the effect of HRT membership on the likelihood of mobilized dissent using country-month data from the Integrated Data for Events Analysis (IDEA) Project from 1990 to 2004. Using a selection model to assess the effect of obligation to the International Covenant for the Protection of Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) on mobilized dissent, we find support for our hypotheses. HRT obligations have a positive effect on the likelihood of mobilized dissent against politically secure leaders when domestic courts are ineffective. When domestic actors will be likely to bring rights claims under an effective domestic judiciary or the leader is vulnerable to turnover, HRT obligations have no distinguishable effect on popular dissent.

This project offers a number of innovations for the scholarly understanding as to how institutions affect mobilized dissent. We argue that institutions that work to constrain repression have a structural effect on dissent, altering the incentive structure in which potential dissidents make decisions. Although treaties and standards can act as focal points to facilitate coordination (Finnemore and Sikkink 1998; Vreeland 2008; Simmons 2009), we argue that these institutions also change the game dissidents are playing. By increasing institutional costs for repression, HRTs create openings for citizens to challenge the state. We also make a clear case as to when a treaty will represent value added to dissidents and when it will do little to alter conflict behavior. Potential dissidents draw their expectations over state repression based on how likely domestic institutions are to constrain authorities. When those institutions create high expectations that authorities will experience consequences, dissidents will not expect a treaty to change that environment. The environment differs far more if an unconstrained government is obligated to a treaty than if the same state is not. International treaties designed to curb rights violations can encourage groups to dissent against the government by opening opportunities for action with less likely repressive consequences—which perversely creates new incentives for the state to further violate human rights.

1 International treaties and mobilized dissent

We define mobilized dissent as a coordinated attempt by a group of non-state actors within the territorial jurisdiction of the state to influence political outcomes outside of state institutions.Footnote 2 Citizens dissatisfied with the status quo act together to threaten to or actually impose costs on the government, using this leverage in the attempt to gain concessions on some policy, resource allocation, or power arrangement.Footnote 3 Mobilized dissent may be legal or illegal, and it can be violent or nonviolent, with dissident actions ranging from peaceful protests to violent riots.

Mobilized dissent materializes in two stages. First, individuals decide whether to incur individual costs to act collectively (mobilization). Next, formed groups threaten to or actually carry out actions that impose costs on the government in an effort to alter the status quo (dissent). Scholars examining how treaties affect social action have focused on the former, arguing that state obligation to international law can help individuals overcome collective action problems. Treaties are argued to decrease the costs of mobilization, but extant literature does little to explain the emergence of collective dissent, which is in part a function of dissident expectations of repression. Because of their potential to constrain repression, HRTs can affect dissent in ways that are counter to expectations from informational stories of treaty effects on mobilization. In this section, we first describe existing scholarly perspectives as to the role of international law in influencing mobilization and then the effect of HRTs on expectations of dissent.

1.1 Overcoming collective action problems

Individuals face a collective action problem when deciding whether to mobilize around an issue or action. Grievances such as inequalities, deprivation, or poor economic conditions create dissatisfaction, which serves as a pre-condition for dissent or rebellion (Gurr 1970; Muller 1985; Weede 1987; Acemoglu and Robinson 2006). When actors desire change to the status quo, they consider joining together, committing to exert resources and effort and assuming the risk of negative government responses (Lohmann 1994; Shadmehr and Bernhardt 2011). Changes in the status quo often take the form of a non-excludable good (e.g., policy change), so individuals face incentives to free-ride and let others bear the costs of collective action (Lichbach 1995). The logical conclusion of the free-rider problem is underprovision (Olson 1965)—no one joins the movement, and desired change cannot occur. To solve this problem, institutions or actors must reduce the costs of mobilization, increase the benefits, or provide information about each (Klandermans 1984; Snow et al. 1986; Klandermans and Oegema 1987; Kuran 1991).

International treaties can reduce the costs of individual participation and facilitate mobilization. Formal or written standards create shared expectations, helping to coordinate individual behavior (Schelling 1978; Weingast 1997; Carey 2000). When states ratify treaties, they agree to be bound to a standard, whether the topic in question is international (e.g., trade policy) or domestic (e.g., environmental policy). Human rights treaties help to coordinate actors’ expectations around state promises for rights protections (Simmons 2009). Treaties set standards as to what the state has agreed to provide, thus highlighting failures to do so (Dai 2005, 384–387). INGOs facilitate this process, educating the populace about new standards and revealing violations of treaty obligations (e.g., Keck and Sikkink 1998; Smith et al. 1998; Simmons 2009). Using these formal standards, actors can more easily agree when a state has transgressed its agreed-upon limits and coordinate to punish authorities accordingly (Weingast 1997).Footnote 4

Obligation to a treaty also sends a signal that the government is willing to consider concessions on a particular issue. Ratification can be a costly process, signaling that the state either values the content of the treaty (sincere ratifiers) or may bend on the issue to obtain short-term benefits or avoid costs (strategic ratifiers) (Simmons 2009). Even states with easier ratification processes can send such a signal; dictators with inclusionary domestic institutions ratify HRTs to satisfy the opposition with a cursory nod to their demands (Vreeland 2008), and others may ratify to signal desire to change practices even if they cannot do so at the time (Hafner-Burton et al. 2008). Because opponents of the status quo expect the leader to be more willing to concede on an issue following treaty obligation, they are more likely to mobilize and challenge the state on that issue (Vreeland 2008; Simmons 2009). By increasing the perceived probability of successful mobilization (cf. Lichbach 1995, 71–74), international treaties can lower the barriers of risk that incentivize individuals free-riding.

International treaties are devices that provide information to coordinate and motivate mobilization, offering an institutional solution to a collective action problem. Most of the scholarship built around coordination concludes that state obligation to HRTs should lead to more mobilized challenges against the state (Keck and Sikkink 1998; Dai 2005; Simmons 2009). Yet mobilization and dissent action are distinct choices (Tilly 1978; Ritter 2014; Shadmehr 2014), and while treaties may affect mobilization through coordinating devices, they also affect repression, which can have the countervailing effect of discouraging dissent.

1.2 Expectations of state repression

Once able to overcome the problems of mobilization, a group’s calculus over dissent includes not only the expected value of changing the status quo but also the risk that the state will repress them (cf. Moore 1995; Ritter 2014). Political opportunity arguments suggest that dissatisfaction is insufficient; groups considering dissent rationally weigh benefits and costs of that action, taking risk into account (Tarrow 1994; McAdam et al. 1996; McAdam 1999; Shadmehr 2014). Rather than dissenting whenever they can rouse a group, dissidents will take action as a function of their expectations of being repressed and likelihood of success.

Repression is a common tactic used by leaders who want to remain in power and control policies to prevent and/or stop mobilized dissent.Footnote 5 Expectations of repression affect dissent in a variety of ways (e.g., Moore 1998; Brockett et al. 2005; Ritter and Conrad2016). Repression can be the unacceptable status quo driving citizens to engage in collective challenges (e.g., Gurr 1970; Opp and Gern 1993; McAdam 1999; Francisco 2004; Cederman et al. 2010; Dugan and Chenoweth 2012), but it can also prevent dissent by restricting group capacity (Sullivan 2015) or invoking fear of severe consequences (Rejali 2007; Ritter 2014). The choice of whether or not to dissent is in part a function of the extent to which a group expects the state to repress; these decisions are endogenous and inferences cannot be straightforward assumptions of linear relationships.Footnote 6

The group’s expectations over repression are formed in part on the basis of the institutional environment that would potentially constrain that behavior. Many kinds of domestic institutions can influence a government’s rights-related behavior (e.g., Keith 1999, 2002; Cingranelli and Filippov 2010; Lupu 2015), but human rights treaties are specifically intended to constrain government repression. These international instruments are legally binding standards of how states should (or should not) treat their citizens. Scholarship on their efficacy is mixed. In the aggregate, scholars have found treaties to have a positive effect on rights protection (Neumayer 2005; Hill 2010; Lupu 2013b), a negative one (Hathaway 2002; Vreeland 2008; Hollyer and Rosendorff 2011), or no effect at all (Hafner-Burton 2005; von Stein 2015). Digging into the details, though, certain treaties have been found to reduce repression in certain states (Hill 2010; Conrad and Ritter 2013), especially when domestic institutions are in place to facilitate implementation (Hathaway 2007; Simmons 2009; Lupu 2013a, 2015). In particular, treaties seem to reduce repression when there is a common expectation that they add terms, standards, and legitimacy to the domestic environment (Simmons 2009).

We argue that an institution does not affect repression alone—it affects the overall conflict between the state and its population. The endogeneity between state repression and popular mobilized dissent makes it important to consider their connection when examining the effect of an HRT on one or the other. Since the ability to repress can have a variety of effects on dissent, so should constraining authorities’ ability to repress. If a treaty affects expectations by structuring the government’s choice, a group’s incentives to challenge the state become ambiguous. Expected constraint may open doors for dissidents to alter the status quo, but the limitation or weakness of that constraint may mean that their increased dissent is met with even more repression. What’s a group to do? Under what conditions will a treaty embolden dissidents?

2 The theory

In this section, we present a theory of how government obligation to a human rights treaty affects the likelihood of mobilized dissent.Footnote 7 In this interaction, a state decides whether to join a human rights treaty; by considering behavior for both types of states, we can derive comparative statics that inform empirical implications. In either history, a government and a group choose a level of repression and dissent simultaneously.Footnote 8 After conflict decisions have been made, outcomes are determined according to conditional probabilities: who “won” the costly lottery, whether the government incurred institutional consequences for repression, and whether the leader will retain power.Footnote 9

Being obligated to an HRT increases the common expected probability that repressive authorities incur litigation costs, as compared to the same state without such an international obligation. Because repression is one part of the conflict with dissidents from the population, this shift in structural incentives (not) to repress affects more than the state’s decision alone. Mobilized groups decide whether to dissent against the state to change a status quo policy or set of policies based on their expectations of achieving their goals and of being repressed.Footnote 10 To assess these expectations and make a decision, potential dissidents look to the expectation that the leader will retain power ex ante to the conflict, the domestic probability of incurring litigation costs, and the state’s HRT status.

2.1 Expectations of leader retention and conflict behaviors

Dissent and repression work against one another in a costly lottery that determines whether the group or the state sets policy at the end of the interaction. We think of this conflict as a simultaneous move: a group and a government must decide how much to dissent and repress in expectation of each others’ moves without seeing them, and their choices affect the conflict outcome. As the government and the dissident group increase the severity or frequency of their conflict actions, respectively, each increases the probability that they will emerge victorious.Footnote 11 For the dissidents, winning means altering the status quo. For the state, more is at stake—losing to the group reduces the leader’s ability to retain power. Leaders lose office for many reasons, both “regularly” and “irregularly.” We assume that the probability of leader turnover or retention is a function of two elements: (1) the leader’s expectations of job security ex ante to conflict and (2) the outcome of the conflict with the dissidents.

Both the leader and the group share a common expectation of the probability that the leader will remain in power prior to any occurrence of repression and/or dissent. We call this common expectation the leader’s ex ante job security.Footnote 12 Many elements inform the ex ante probability of retaining power, including observable aspects of personal characteristics like age and experience, the institutional means available to remove a leader from office, and policy outcomes during his or her tenure. Is s/he personally weak, untested in office, subject to a called election, or overseeing a weak economy? These characteristics (and others like them) set the stage for the conflict with a potential dissident group.Footnote 13

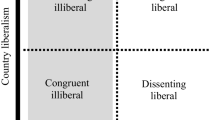

The outcome of the conflict—whether the government or the dissident group wins the conflict and thus controls the policy in question—modifies the probability that the leader loses office. Figure 1 illustrates our conceptualization of how the actors’ conflict choices indirectly affect a leader’s probability of retaining or losing power. A leader’s ex ante job security is the common expectation of the variety of institutional and behavioral elements that influence how likely s/he is to retain power. The chosen level of repression combines with the group’s level of dissent in a costly lottery that determines who, at the end of the day, will set the policy. If the government retains control over the status quo policy, even after facing dissent, there is no change to the leader’s probability of remaining in office. If, by contrast, s/he loses policy control to the group, the leader’s ex post job security will be lower than his or her pre-conflict security.

When a group wins and a leader makes concessions, altering the status quo in the interests of an actively dissenting group, it becomes more difficult for the leader to retain the necessary support to hold power. Such a loss of control threatens the leader’s legitimacy, suggesting that some constituents believe he sets bad policies or is otherwise not fit to rule (Davenport 1995). Further, concessions to the group move resources away from those who support the leader in power (see, e.g., Bueno de Mesquita et al. 2003).Footnote 14 A leader who cannot control policy-setting in the context of a challenge will be more likely to lose office than a leader with the same level of security who wins the day and can maintain the status quo. In short, the actors’ conflict choices determine who controls policy; the policy outcome modifies a leader’s pre-existing job security to decrease his or her ultimate probability of retaining office.Footnote 15

The more secure a leader is in office, the more a group will dissent—more is required to counter the leader’s repression. Secure leaders—ones who are more likely to remain in office prior to repression and dissent choices—have the most to lose if a conflict with dissidents leads to their ousting. Imagine a middle-aged leader who expects to be in power into his nineties. For that leader, losing policy ground or resource allocations to dissenting groups—and its attendant dip in publicly perceived legitimacy—has a major impact on what would otherwise be a sure retention of power. Experiencing dissent does not affect the compound probability of losing power, but losing policy ground to a group does, and this effect is much more pronounced if the leader otherwise would have little reason to anticipate turnover. Consequently, as a leader becomes more ex ante secure in office, s/he has increasingly strong incentives to repress to put down dissent and maintain control over the status quo, even though repression is costly. By comparison, if a leader expects to step down for some other reason—like a term limit or poor economic outcomes—the benefit of repression is low, since s/he is likely to lose office anyway. Leaders with a high ex ante expectation of remaining in power are playing a higher stakes game and so are prone to repress more than comparatively vulnerable leaders.

Expecting this, dissatisfied groups will dissent at higher levels as a leader is more secure in office. The group wants to dissent as severely as possible to receive its preferred policy but is limited by resource constraints. Dissidents want to cause just enough trouble to maximize their chances of altering the policy in question, and no more. When leaders are particularly secure in power, low levels of dissent won’t work: the group’s efforts are likely to be subsumed by state repression. The group must increase dissent as they expect the leader to increase repression, making the most efficient use of dissent tactics in the effort to emerge from the interaction victorious. Therefore, dissent increases with the leader’s ex ante job security.

2.2 Institutional constraints and their effects on dissent

In addition to being costly in terms of resources, repression is associated with a probability that the leader or repressive subordinates will incur institutional consequences. Every domestic legal environment produces some variable probability that a claim will be brought against authorities who repress, and the process of litigation is a costly one. Victims or advocates can bring cases against the state for violating their civil rights and liberties, citing relevant domestic or international law for the obligation to protect them (Hathaway 2007; Powell and Staton 2009; Simmons 2009). Experiencing litigation creates meaningful costs for the targeted authorities that they would prefer to avoid: they must expend resources responding to the accusations and defending themselves in court, and there may be negative publicity they must counter or silence. These litigation costs exist even if the government is not found in violation of the law (Powell and Staton 2009). Of course, the judicial costs are higher if the court finds against the state, but this is not necessary for the potential for litigation to create institutional and reputational costs the government would prefer to avoid. A leader who expects litigants will be willing to bring legal claims against state authorities will be less likely to engage in repression (Cross 1999; Hathaway 2007; Powell and Staton 2009), especially if the barriers to litigation are low (Lupu 2013a).

Obligation to an HRT increases common expectations of domestic litigation for a number of reasons. First, international standards often add to the canon of domestic law (Powell and Staton 2009; Simmons 2009). Ratification obliges states to adopt treaty terms, adding to or clarifying existing domestic laws regarding rights protections.Footnote 16 International court rulings further add to domestic canon in many systems (Helfer and Voeten 2014), increasing the referents and case law for claimants to draw upon. The adaptation or expansion of domestic law can increase the number or variety of situations for which the repressive state could be brought to court (Simmons 2009). Second, victims may believe there is increased legitimacy or support for their claim if there is an international standard in addition to a domestic obligation to protect rights, increasing their willingness to litigate (Keck and Sikkink 1998). Third, obligation to a human rights treaty encourages NGOs to train lawyers to bring cases against the state (Smith et al. 1998). For example, the Association for the Prevention of Torture has worked to train lawyers in Thailand to use the terms of the Convention Against Torture in domestic court cases on behalf of victims.Footnote 17 In these ways, the international legal obligation increases the probability state authorities will face litigation-related resource and political costs for violating rights. More importantly, the obligation increases the expectation that the leader will face legal costs, thereby affecting both the government’s and the group’s behavior.Footnote 18

For a treaty obligation to change repressive behavior from what it would have been if the same leader were not obliged to the treaty, we must consider the marginal change in the likelihood of litigation costs associated with the obligation. How likely would it be that repression would land the leader in court without the treaty obligation, and how would that probability differ under the treaty? There are many reasons why repression might be more likely to see trial in one uncommitted state as compared to another: there are more domestic laws defining rights protection, a higher number of NGOs are searching for victims and experienced in litigation, individuals have prosecutorial rights, the judiciary enjoys popular support, etc. When there is a high expectation of litigation for repression based on the domestic system alone, obligation to an HRT does little to change that already high probability. International terms will add few legal referents, NGOs are already active, etc. Leaders under such a domestic legal situation would have little reason to alter their repressive strategies under obligation to an HRT.

By contrast, HRT obligations bring sufficient legal and behavioral changes to boost the baseline expected probability of litigation by a significant amount if that baseline is otherwise low. The treaty obligation represents a clear value added in the environment of constraint. But how can this arguably small change in legal standards affect dissident expectations and behavior in states where people do not usually expect to find redress in courts? Carrubba (2009) argues that the early stages of change in the legitimacy of judicial institutions provide meaningful opportunity for litigants to push boundaries as to what a court would previously not do. Courts lacking independence and legitimacy must operate in close alignment with the executive’s preferences (Helmke 2002, 2005). As a court builds its legitimacy toward its limited purpose, however, public support (Vanberg 2005; Staton 2010) and adventurous lawyers and litigants (Rosenberg 1991) can push a court to foray into new waters (Carrubba 2009). Egypt provides an example. At its inception, the constitutional court lacked independence and was unable to bind government behavior in any area. Finding a need for credible commitments when it came to international financial relations, the government ceded some power to the very weak constitutional court for the enforcement of property rights. Domestic human rights organizations, seeing a small opening, began to bring human rights-related cases, despite no evidence that the court would rule in their favor. Not only did rights litigation increase, but the court did occasionally rule against the state in cases of repression (Moustafa 2003, 2007). This case and others (see, e.g., Hilbink 2007; Helmke 2005; Carrubba 2009; Staton 2010) suggest small shifts in the incentive structures surrounding even very weak courts can lead people to seek redress.Footnote 19

2.3 Empirical implications

Groups prefer not to act if dissent is unlikely to yield their desired outcome, and the expectation of whether the group will successfully alter the status quo depends on the leader’s choice of repression. Unable to observe the actual likelihood of repression while making decisions, groups must look to observable things—like the leader’s job security and the presence of institutional constraints—to predict whether authorities will repress their dissent efforts. These variables interact, conditioning our expectations as to how treaties will affect dissent behavior.

Institutions only alter a group’s behavior if they were going to dissent otherwise. A group that stays at home because there’s no reason to dissent cannot be said to have been effected by treaty status. So we must first suggest when dissent will be most likely—which is when repression is most likely. As discussed above, the relationship between dissent and repression is a complex one. Here, we made the simplifying assumption that the conflict is a costly lottery of effort, and the more a group dissents relative to repression, the more likely it is to alter the status quo. Therefore, the conditions that make a leader repress more also make the group dissent more in kind.Footnote 20 We expect that leaders who are vulnerable to turnover are likely to lose office regardless of the conflict outcome and so will be less likely to use resources to repress. Therefore, dissidents need not dissent much to get what they want from a leader heading out the door. With such low dissent under insecure leaders, the institutional environment does little to change conflict choices. Treaties, and their associated increase in the domestic probability of litigation, will have no effect on dissent choices when the common expectation of the leader’s security in power is low.

Implication 1.

When the baseline probability the leader will remain in power is low, HRT obligation has no effect on mobilized dissent.

Furthermore, we argue obligation to an HRT will only affect dissent choices when it represents real value added to the domestic constraint environment. An HRT does not alter the constraining incentives when the probability of litigation is already high. Since the group should expect little or no difference in a state’s repressive strategy as a function of its treaty status, treaty status will not effect dissent choices when authorities already face meaningful constraints.

Implication 2.

When the baseline domestic probability of litigation is high, HRT obligation has no effect on mobilized dissent.

The more the leader and state agents repress, the more vulnerable they are to litigation. More victims can bring suit, more publicity piques the attention of advocates, more evidence accumulates against authorities—all of which make it easier to litigate, which is costly for the leader. Since ex ante secure leaders will repress more to retain that security, the expectation of litigation has a greater restraining effect than it does on leaders who would repress less. Leaders who expect to lose office regardless of conflict outcomes have little to fear from possible litigation, because they repress at lower levels and they do not expect to be in power to bear the costs.

Obligation to an HRT has the greatest constraining effect on repression when (a) the baseline domestic probability of litigation for repression is low and (b) the probability the leader will remain in power outside of conflict is high. A low domestic probability that repression would yield litigation costs is the prime counterfactual condition for the addition of an HRT membership to increase those potential costs by a large amount. A treaty obligation should lead to the greatest change in the leader’s and group’s decision-making structure when this is the case. However, the altered constraint only leads to changed behavior when the leader would repress enough to be bothered by it. Leaders who expect that they would remain in power if they won but would have a lot to lose in conflict will be the ones who repress at the highest levels—and so be most affected by the higher probability of litigation costs associated with the HRT obligation.

This increased constraint from the treaty obligation creates opportunities for the group to dissent. HRT obligation does not change the relative costs or benefits of dissent directly; the increased threat of litigation constrains the leader’s ability to engage in repression as s/he would be wont to do in the absence of the obligation, which creates new opportunities for the group to take advantage of that higher constraint to demand their desired change. Groups will be more likely to dissent if they expect the action will yield their desired shift in policy, and that is most true when the leader is constrained from repressing as much as s/he would have liked to counter the group attack. Dissidents expect HRTs to yield this advantage when the leader would have otherwise repressed the most (when secure in power) and when the treaty represents a large marginal change in the likelihood of repression litigation (when the domestic legal baseline is low), and so the treaty has the greatest effect on increased dissent under these conditions.Footnote 21

Implication 3.

When the baseline domestic probability of litigation is low, HRT obligation has an increasingly positive effect on the likelihood of mobilized dissent as expectations that the leader would remain in power outside of conflict increase.

3 Empirical analysis

We analyze the implications of the theory by estimating the likelihood of mobilized dissent as a function of obligation to international human rights law. Our sample includes 147 countries from 1990 to 2004, analyzed at the country-month level of observation.Footnote 22

3.1 Research design

For the dependent variable, we need a measure that provides information on the extent to which domestic non-state actors engage in mobilized dissent against the government. Although there are several cross-national measures of Mobilized Dissent available at the country-year unit of observation, these measures are inappropriate for our use. First, these indicators often include information on repression in addition to mobilized dissent;Footnote 23 the theory requires separate empirical indicators of the two concepts. Second, most commonly used data on mobilized challengesFootnote 24 are only available at the country-year unit of observation.Footnote 25 Given that dissent and repression vary so much within a year, and that temporal aggregation of events data can bias parameter estimates (Shellman 2004), we use a less aggregated measure of dissent.Footnote 26 We use data from the Integrated Data for Events Analysis (IDEA) Project (Bond et al. 2003; King and Lowe 2003), which codes events from daily reports of the Reuters Global News Service from 1990 to 2004,Footnote 27 and aggregate the data to the state-month level of analysis.

The IDEA framework provides information on many types of events and identifies targets and sources of violent and non-violent behavior, allowing us to create a count of incidents in which a domestic non-state group took a conflictual action against the government. The variable in our estimates is a dichotomous indicator of Mobilized Dissent coded 1 in a given country-month if a domestic non-state group engages in any action coded as “conflictual” according to the Taylor et al. (1999) Conflict-Cooperation Scale, targeted at a state actor.Footnote 28 This operationalization allows us to estimate the continuous, latent likelihood of observing an act of mobilized dissent against the state.Footnote 29

The primary independent variable is HRT Obligation. Although there are a variety of treaties intended to improve state respect for human rights, we analyze the implications using data on obligations to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). Investigating the effect of HRT obligation on mobilized dissent using this treaty is appropriate for several reasons. First, we prefer to test the effect of a broad treaty that focuses on constraining the state from violating multiple rights. A more specific treaty, such as the Convention Against Torture, only hopes to constrain authorities from using one type of repression, which they could easily substitute with another. Expecting substitution, dissidents are unlikely to alter their dissent choices. The broader ICCPR prohibits the use of many civil and political rights violations that are common forms of repression, so if it affects state behavior, it should affect it in a way that would motivate dissidents to expect an opening in the opportunity for dissent. Second, the treaty represents restrictions on different types of rights issue areas, governing both the protection of empowerment rights (e.g., voting, assembly, speech) and physical integrity rights (e.g., the right to be protected from torture, political imprisonment); these rights are intended to be for all people. If we find empirical support for treaty effects on dissent for this treaty, this should allow us to generalize our findings and expectations for a wider range of HRT types, both more specific and more general. HRT obligation is coded 1 in the country-month during which a county ratifies (or accedes to) the ICCPR, and 1 every year thereafter.Footnote 30

To gauge the probability that a leader experiences litigation for repression in the absence of HRT obligations, we consider a state’s level of domestic judicial effectiveness. Powell and Staton (2009, 154) define a judiciary as effective if it “constitutes a genuine constraint on state behavior.”Footnote 31 Under such conditions, victims will expect to find redress in the court, and so are more likely to seek it. An effective court will rule against repressive leaders with or without the international standard, and potential complainants expect as such and litigate freely (Keith 2002). Victims are likely to have little faith that a case will be fairly heard in a comparatively ineffective judicial system. Recall from our theory that a court need not rule that authorities have violated rights to create costs; having a case brought to court creates costs authorities would reduce repression to avoid. We use judicial effectiveness to approximate dissidents’ expectation of the probability that victims or advocates would bring a case against a given act of repression.

We require a measure of Judicial Effectiveness that accounts for several concepts: (1) whether judges are permitted to rule without interference (Keith 2002; Staton and Moore 2011), (2) whether judges’ rulings are translated into policy or practice (Cameron 2002; Staton and Moore 2011), and (3) whether the population believes the court is effective according to points (1) and (2) and is inclined to use it (Powell and Staton 2009). Unfortunately, measurement of domestic judicial effectiveness is not a straightforward enterprise. Many are available only for a limited temporal domain, and non-random missingness is a problem across many indicators.Footnote 32 To deal with these difficulties, Linzer and Staton (2015) use a heteroskedastic graded response item response theory model to cull information from eight existing measures of judicial independence, rule of law, etc. to capture the underlying latent concept of judicial effectiveness (LJI). The information from these constituent measures means the final continuous indicator (which ranges from 0 to 1, where higher values on the scale represent higher levels of Judicial Effectiveness) captures both what the court does and what the population expects as an outlet for remedy.Footnote 33

Potential dissidents also make decisions about dissent as a function of their expectations that the leader would remain in power outside of the repression-dissent interaction. We argue that leaders make decisions over how to handle the threat from the group based on how likely they are to hold office and expectations of how that would be effected by a policy loss to the group. We need to capture the former—the pre-decision probability of remaining in power—to operationalize the cues the group would use to anticipate the leader’s decision.

Like the group, we use observable characteristics and policy outcomes to form an estimate of the leader’s pre-conflict staying power. Cheibub (1998) uses parametric survival models to create estimates of job insecurity based on the leader’s time in office to date, previous trends in leadership change, and annual economic growth. Because we require data at the country-month unit of observation, we estimated survival models predicting a leader’s risk of losing office using data on leader characteristics from Archigos (Goemans et al. 2009) in a given month as a function of time-to-date in office, previous trends in leadership change, and economic growth at that unit of observation. The estimated hazard of job insecurity ranges from 0 (lowest probability of turnover) to 1 (highest probability of turnover). We reverse the scale to create our final measure of Expectations of Executive Job Security.Footnote 34

Finally, we account for Repression, for which we again use IDEA event data. We created a count of all events in which a state actor targets a non-state actor within its territory with any action coded as “conflictual” short of civil war according to the Taylor et al. (1999) Conflict-Cooperation Scale. We dichotomize the count and use a binary indicator coded 1 in a given country-month if the state engaged in any of the qualifying repressive behaviors.

We restate our empirical implications in terms of these measures of our concepts:

Hypothesis 1.

When expectations of executive job security are low, HRT obligation has no effect on the likelihood of mobilized dissent.

Hypothesis 2.

When the domestic judiciary is relatively effective, HRT obligation has no effect on the likelihood of mobilized dissent.

Hypothesis 3.

When the domestic judiciary is relatively ineffective, HRT obligation has an increasingly positive effect on the likelihood of mobilized dissent as expectations of executive job security increase.

3.2 Error structure specification

One of the difficulties of determining the effect of HRT obligations on domestic outcomes is that selection into international treaties is non-random. The factors affecting compliance with a treaty also affect the decision to commit to international law in the first place. Although this point is made often in studies on the effect of HRT obligation with regard to repression (e.g., Vreeland 2008; Powell and Staton 2009; Hill 2010), it is equally relevant for mobilized dissent. We argue that the same domestic factors that affect the group’s decision to engage in mobilized dissent are partially correlated with the state’s decisions over treaty obligation and repression. Empirically, this means that one-stage statistical models do not allow us to determine whether committed states face different dissent patterns from non-committed states because of treaty obligation or as a result of preexisting domestic conditions that determine both.

Selection models are often used for this purpose, but our data provide us with more information than scholars typically have when they turn to a standard Heckman (1979) model. Typically, scholars turning to selection models only have information on (and predictions over) the outcome variable for selected observations (HRT-obligated states), but we have expectations and data regarding dissent in both HRT-committed and uncommitted countries. The problem with studying the effects of treaty obligations is that it is impossible to observe (1) dissent outcomes that would have occurred in non-signatory states if they had committed to an HRT, and (2) dissent outcomes that would have occurred in committed states if they had not adopted the obligation. We use a selection or treatment model similar to that of Von Stein (2005) to estimate the average treatment effect using these counterfactuals. The estimator is similar to a traditional selection model in that it accounts for both observed and unobserved factors that affect state decisions to ratify international law. While a Heckman (1979) model estimates a selection equation and then the effect of that treatment on the selected group, the treatment model estimates an additional outcome equation of the likelihood of the outcome for the non-selected group. The model allows us to imagine a counterfactual in which all non-signatory states commit to an HRT, as well as a counterfactual in which signatory states do not commit to an HRT.

We include measures of judicial effectiveness, expectations of executive job security, and repression in the selection stage to determine the effect of HRT obligation on mobilized dissent. To meet the exclusion restriction, we include the number of intergovernmental organization (IO) memberships a state maintains during a given year. This captures a state’s affinity for international obligations, including those not related to human rights such as trade or alliances. Obligation to international law in other areas is unlikely to be related to dissent; obligation to a trade agreement should not alter a group’s expectation of repression. Our measure comes from the Intergovernmental Organizations Data Set and ranges from one to ten (Ulfelder 2011).

In accordance with our conditional hypotheses predicting Mobilized Dissent, we interact our primary explanatory variables. We expect the effect of HRT obligation on dissent to be conditional on a leader’s baseline job security, as a function of the effectiveness of the domestic judiciary. The treatment model estimates the process of obligation to each of the treaties in the selection stage, so we interact the remaining two predictive variables in the selection and outcome equations: Judicial Effectiveness and Expectations of Executive Job Security.

3.3 Empirical results & discussion

When the judiciary is relatively ineffective, we predict HRT obligation will have a positive effect on dissent only when leaders are sufficiently secure in office; when the court is comparatively effective, obligation will have no effect on dissent. Table 1 presents estimates of the effects of the independent variables on the likelihood of mobilized dissent.Footnote 35 Bootstrapped standard errors are reported in parentheses.Footnote 36 The first column of Table 1 lists results for HRT-committed states, and the second reports results for states that have not committed to the ICCPR.

We cannot draw inferences about the effects of HRT obligations on dissent from Table 1 alone. We compare the empirical results to two estimated counterfactuals: one in which all countries that have not committed to a treaty are made to ratify—the average treatment effect for the controls (ATC)—and one in which all countries that committed to a treaty are made to renege on their obligation—the average treatment effect for the treated (ATT). We can examine the expected difference in the likelihood of mobilized dissent that derives from the treatment across these outcomes to determine the effect of the treaty.

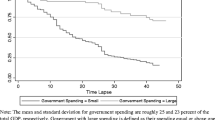

Figures 2 and 3 illustrate the average treatment effect for control cases and treatment cases, respectively, of obligation to the ICCPR on the probability of dissent across the range of job security in states with (a) ineffective domestic courts and (b) effective domestic courts.Footnote 37 To create the ATC figures (Fig. 2), we estimated the predicted probability of dissent occurring in an average state-month using the parameters estimated for uncommitted states and the mean values of the independent variables within the uncommitted sub-sample. Next, we used the same mean values of our independent variables for uncommitted states and the estimated parameters for obligated states to estimate the predicted probability that dissent would have occurred if an uncommitted state were obligated to the ICCPR. This strategy allows us to observe the effect of treaty obligation across hypothetical states that only differ on one dimension: treaty obligation. The solid lines show the difference in these estimates across the observed range of job security, illustrating how committing to the ICCPR would change the predicted probability of mobilized dissent for the control sample of unobligated states.Footnote 38 The estimated effect is statistically significant when the bounds of the ninety-five percent confidence intervals (the dashed lines) do not encompass the zero line.

Average Treatment Effect (ATC) of ICCPR obligation on the Pr(Mobilized Dissent) as Expectations of Executive Job Security Increase in States with a Ineffective Courts (defined as the sample minimum of judicial effectiveness) and b Effective Courts (defined as the sample maximum of judicial effectiveness) for the Control Cases. Estimates using alternative values of judicial effectiveness are in the Online Appendix

Average Treatment Effect (ATT) of ICCPR obligation on the Pr(Mobilized Dissent) as Expectations of Executive Job Security Increase in States with a Ineffective Courts (defined as the sample minimum of judicial effectiveness) and b Effective Courts (defined as the sample maximum of judicial effectiveness) for the Treated Cases. Estimates using alternative values of judicial effectiveness are in the Online Appendix

Figure 2 suggests support for the theory. In Fig. 2a, domestic courts are relatively ineffective. The probability of observing dissent increases significantly if an unobligated state were obligated to the ICCPR—but only when dissidents face leaders who are secure in power. On the left side of Fig. 2a, citizens seem to be no more or less likely to challenge the government as a function of obligation to international law when leaders are likely to lose office anyway. However, on the right side of Fig. 2a, when the executive is sufficiently secure in power, there is a statistically and substantively meaningful increase in the probability that a group will engage in dissent against the government connected with state obligation to the ICCPR. This is consistent with our theory that dissatisfied groups will be more likely to take mobilized action against the state under HRT obligations, believing the government to be more constrained from repressing them than it would be without the international obligation.

Yet, as expected, this is only the case when the judiciary is comparatively ineffective, because the treaty obligation alters citizens’ expectations of state constraint in ways the domestic judiciary cannot do alone. In Fig. 2b, the judiciary is quite effective on its own, and there is no discernible effect of ICCPR obligation on the probability of dissent, regardless of the level of executive job security. When the court is sufficiently effective in its own right, groups do not expect obligation to the ICCPR to constrain the leader from repressing much more than domestic institutions already do. Therefore, the obligation has no effect on their choice to dissent.

Figure 3 illustrates the Average Treatment Effect for the Treated (ATT). The marginal change in the predicted probability of mobilized dissent was calculated in the reverse manner of Fig. 2: we estimated the probability of mobilized dissent for the average ICCPR-obligated state, estimated what the same state would do if it with only its treaty status changed, and subtracted the latter from the former. According to our theory, we expect that if a state that is committed to a treaty were to revoke that commitment, mobilization would decrease in states with ineffective judiciaries and sufficiently secure leaders. To rephrase, a treaty-obligated state that would have a given level of dissent would have comparatively less dissent if it were not obligated. These figures support this prediction. Once again, treaty status has no effect on the probability of dissent in states with sufficiently effective judiciaries (Fig. 3b), but treaty status has a meaningful negative effect on dissent in states with weak domestic constraints and secure leaders who would be more free to repress in the absence of the treaty than under its legal obligation.

4 Conclusion

We argue that state obligation to international human rights law can incentivize dissent. More precisely, an international obligation to protect human rights leads to a meaningful reduction in repression (cf. Conrad and Ritter 2013), which allows for an increase in popular dissent. These effects are conditional on domestic political structures. HRT obligation leads to increased mobilized dissent only in states where leaders are secure and domestic courts are ineffective.

This project represents an important contribution to our understanding of the effects of international treaties on domestic politics. Studies have suggested that citizens mobilize in support of HRTs, but few focus specifically on dissent as a dependent variable. We build on the work of Simmons (2009), which argues that treaties lead populations to expect that dissent is more likely to be successful. We explicitly theorize this claim, arguing that citizens will be more likely to take costly action against the state because they expect the treaty to constrain leaders from repressing them. While Simmons (2009) examines how regime type conditions this expectation of success in her study of its effects on repression, we focus on the leader’s sensitivity to removal—a more precise signal of the group’s ability to threaten him to alter the status quo.

We integrate these ideas into a cohesive theoretical framework of domestic institutions and popular behavior. HRTs affect citizens’ expectations of repression as a function of the probability of legal constraint and the leader’s need to use it to stay in power, and both of these enter into groups’ calculations of optimal outcomes. Our findings suggest that treaties affect dissent as more than a focal point for overcoming collective action problems—they also structure the interaction between the mobilized group and state authorities. Written obligations do provide important information to actors considering dissent, helping to identify common ideas of state transgressions and increasing expectations of cooperation. While this understanding of treaty effects on dissent is very likely true, it is insufficient to explain when a group willing to incur the costs of dissent actually engages in this costly activity. Deriving implications from a theory that includes a strategic interaction with a repressive government, we find that treaty obligation can impact the likelihood of mobilized dissent by creating a constraint on state responses.

We thus add to the scholarly understanding of how international institutions affect social behavior; we consider the consequences of mobilized dissent in a theory of domestic conflict. By affecting a leader’s ability to repress, HRTs open space for dissent. Studying how citizens respond to these opportunities in the expectation of a repressive state response allows us to learn a great deal about how HRTs affect popular decision-making in light of structural changes.

In particular, HRTs have the largest effect on dissent when the judiciary is relatively ineffective. This result obtains because we model repression and dissent in the absence of the treaty obligation and predict differences in its presence. Effective judiciaries largely constrain leaders from violating rights with or without an obligation to an international standard of protection. Under these circumstances, repression and dissent remain comparatively low, and obligation to a treaty does little to shift these behaviors. However, ineffective judiciaries represent a low baseline of legal constraint on leaders who would choose to repress, and overall levels of repression are much higher. This low constraint shifts significantly with the introduction of new legal standards and the attendant popular expectations, such that we see the greatest magnitude of HRT effects on repression—and therefore dissent—when the judiciary is ineffective. In short, international treaties have their strongest effect when states lack the domestic mechanisms to constrain leaders, leading to increases in popular action against the state. This runs counter to existing scholarly expectations that courts need to be effective to enforce HRT obligations.

Because they influence both state repression and dissent, HRTs have potentially divergent effects: when they are most effective at constraining state violations of human rights, they potentially provide incentives for citizens to dissent against the state. Consequently, even when treaties successfully constrain human rights violations, they may indirectly increase incentives to repress via their effects on popular dissent. Effective domestic courts potentially provide a solution: when states with secure leaders have ineffective courts, dissent increases with HRT obligation, providing indirect incentives to repress. But when these states have effective courts, groups are not more likely to dissent, leaving state authorities more constrained, but less subject to threatening challenges than they otherwise would be.

Notes

Excepting this rule, Murdie and Bhasin (2011) find that international non-governmental organizations (NGOs) with activities on the ground are connected with an increase in the incidence of domestic protests.

Although domestic institutions and behaviors are often more salient to those considering mobilization than international forces, their presence and effects do not preclude treaties from having a separate or supporting effect in facilitating mobilization.

One of the most consistent arguments in political violence is that state authorities respond to domestic threats with repression (cf. Davenport 2007a). For more on repression in response to dissent, see, e.g., Poe and Tate (1994), Gartner and Regan (1996), Moore (2000), Regan and Henderson (2002), and Carey (2006).

We do not explicitly theorize the mobilization stage. If members of a group are sufficiently coordinated such that they could act collectively, we model the group’s decision to act or not.

We assume both repression and dissent require resources and effort that increase with the severity of the action, making them costly for the actors.

This is an informal presentation of a formal model, which we have relegated to the Supplementary Appendix.

Dissidents can take action against the state for any reason; they need not dissent for policy change related to the terms of a particular HRT. All that matters is that they believe authorities who repress will be a small amount more likely to face costs as a result of HRT obligation—no matter the reason for the dissent.

The actors can choose any form or amount of repression and dissent, respectively, including not to repress or dissent at all. Repression at level 0 is the equivalent of accommodation, granting concessions to the group, while refusal to dissent accepts the status quo. See Ritter (2014) for a similar set of assumptions.

We assume actors have the same expectation of the leader’s likelihood of retaining power. This is because our concept of the probability of retention is based on the accumulation of a number of observable determinants of a leader’s hold on power in addition to some amount of error; it is an estimate, as we discuss in depth with regard to operationalization below. It is an estimate made by both actors, drawing on elements from the observable world and including some error. It is possible that leaders may have more information that might reduce the variance of their estimates, but that should not necessarily bias the average estimate away from that of the group.

This is likely to be true when the dissidents are not members of a winning coalition (which, as those dissatisfied with the status quo, they rarely are).

In making the assumptions illustrated in Fig. 1, we assume that it is not the act of repression itself that leads to retention or removal from office, though that act does entail costs to the leader in the form of resource costs. Nor does dissent itself oust a leader or encourage others to do so. Instead, we assume that it is the policy outcome of the interaction that matters to the supporting coalition that would keep a leader in power. Regardless of the size of that coalition, the in-group wants the government to retain resources for distribution to them. If the leader retains those resources, it matters not how much s/he repressed an out-group to retain them. If, however, the leader loses some of those resources to a group such that they cannot be distributed to the coalition, s/he is less likely to remain in power.

Despite the increased risks associated with treaty obligation, there are a variety of benefits that tempt the state to ratify. These benefits may be short- or long-term, domestic or international, normative or self-serving. See, e.g., Hathaway (2003, 2007); Hafner-Burton et al. (2008); Vreeland (2008); Simmons (2009).

“Thailand: Implementing the UN Convention Against Torture.” Accessed January 19, 2011 at http://www.apt.chi.en/. See Merry (2006) for additional examples.

In some states, international law must and will be incorporated into domestic law, but this need not happen for our theory’s predictions to hold. If the authorities and the population expect the state to experience even a small increase in the likelihood of incurring litigation costs—through the court’s increased likelihood of hearing a case, even if it rules in favor of the state—as the result of an international obligation, this changes the incentive environment enough to affect dissident behavior according to our theory.

This is not to say that potential dissidents themselves bring legal claims against the HRT-committed leader; the expectation that authorities will be brought to court by anyone experiencing repression activates government constraint and thus affects the group’s dissent strategy.

Many scholars have found different directional relationships (e.g., Lichbach 1987; Moore 1998, 2000). Shellman (2006), Pierskalla (2010), and Ritter (2014) argue the conflicting findings in the literature have arisen because scholars have not derived predictions from a strategic understanding of the interaction.

Although individuals may not be aware of HRT obligation status, they respond to changes in popular expectations about repression. NGOs play a vital role in providing information about rights and HRT ratification status, influencing citizen expectations of repression and dissent.

A number of analyses with additional or different variables or specifications are available in our Supplemental Appendix. Replication files will be made available on the authors’ websites and the website of this journal.

For example, data from the Political Risk Service and the World Governance Indicators combine information on opposition mobilization and the government’s response.

Data from the Cross-National Time-Series (CNTS) Data Archive (Banks 2010) is an example.

Other data are available at lower levels of temporal aggregation for one or few countries (e.g., Rasler 1996).

Results are robust to using country-year observations, as shown in the Supplementary Appendix.

Using data that relies on international news reports comes with bias that could potentially influence our results. Some countries have a larger media presence than others, such that stories will be more likely to be reported from there than a country with just as much dissent but fewer reporters. International reporters also tend to focus on bigger, more violent events while more minor events are less likely to be reported. Our measure of dissent, which is described in more detail in the Supplementary Appendix, includes very low-level events but may still miss smaller, local events. This should bias our estimates toward finding no effect on dissent outcomes.

These data are described in more detail in Ritter (2014) and its online materials, as well as in the Supplementary Appendix.

This measure essentially treats any dissent event of any size or level of violence as the same. The formal theory technically assumes the group will choose a level of dissent from a continuous range, such that obligation to a treaty should lead to a lower level of dissent under certain conditions. For purposes of empirical estimation, we translate this concept as the continuous likelihood of observing a dissent event. For a discussion of the conceptual difference between likelihood and level of conflict events, see Ritter (2014).

We are interested in the long-term effect of the obligation, rather than the effect of initial ratification. It is possible that a treaty alters state behavior from one year to the next much less after it has been committed for many years than it did in the years immediately after ratification. However, our theory does not assume that a group looks to changes in actual behavior from year to year to make its decisions. We argue that the treaty effects dissident behavior if a group acts differently in a state that is so obligated than it would if the same state were not obligated to the treaty. If a group in a state that has been obligated to the ICCPR for ten years acts differently than it would if the same state were not so obligated, then the treaty alters behavior. Therefore, states do not drop out of our sample in the country-months following ratification.

For more on the variety of empirical indicators of judicial effectiveness, see Ríos-Figueroa and Staton (2014).

LJI is conceptually the best available approximation of the theoretical concept we present here, but using a country-year measure in a country-month analysis means that we assume no change in Judicial Effectiveness within a given year. Because institutions are “sticky” for a variety of reasons (e.g., Grief and Laitin 2004; Page 2006) and domestic court effectiveness is unlikely to change rapidly (e.g., Staton 2006; Carrubba 2009), we do not think this unreasonable.

The likelihood of losing power in a given country-month is low, so the measure is highly skewed toward one. We use additional measures of job security in the Supplementary Appendix.

Expectations of Executive Job Security and Judicial Effectiveness are both predicted values. Introducing the errors of estimation requires a recalculation of the variance-covariance matrix, requiring bootstrapping.

For both Figs. 2 and 3 we classify an ineffective judiciary as a state with the sample minimum of judicial effectiveness and an effective one with the sample maximum. We replicated these figures at each tenth percentile to show that the conclusions are robust to a number of different cutpoints; these are presented in the Supplemental Appendix.

We follow Brambor et al. (2006) and subtract the first calculated predicted probability from the second predicted probability and repeat this process at each 0.01 interval of Job Security from 0.9 up to a value of 1.0 (its maximum possible value) and graph the first difference across the observed range of job security.

References

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J.A. (2006). Economic origins of democracy and dictatorship. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Almeida, P.D. (2003). Opportunity organizations and threat-induced contention: protest waves in authoritarian settings. American Journal of Sociology, 109(2), 345–400.

Banks, A.S. (2010). Cross-national time-series data archive. Jerusalem: Databanks International. See URL: http://www.databanksinternational.com.

Beck, N., Katz, J.N., & Tucker, R. (1998). Taking time seriously: time-series-cross-section analysis with a binary dependent variable. American Journal of Political Science, 42(4), 1260–1288.

Bell, S.R., Bhasin, T., Clay, K.C., & Murdie, A. (2014). Taking the fight to them: neighborhood human rights organizations and domestic protest. British Journal of Political Science, 44(4), 853–875.

Bond, D., Bond, J., Oh, C., Jenkins, J.C., & Taylor, C.L. (2003). Integrated data for events analysis (idea): an event typology for automated events data development. Journal of Peace Research, 40(6), 733–745.

Brambor, T., Clark, W.R., & Golder, M. (2006). Understanding interaction models: improving empirical analyses. Political Analysis, 14, 63–82.

Brockett, C.D., McAdam, D., Tarrow, S.G., & Tilly, C. (2005). Political movements and violence in Central America. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bueno de Mesquita, B., Smith, A., Siverson, R., & Morrow, J.D. (2003). The logic of political survival. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Cameron, C.M. (2002). Judicial independence: how can you tell it when you see it? And, who cares? In S.B. Burbank, & B. Friedman (Eds.), Judicial independence at the crossroads: an interdisciplinary approach (pp. 134–47). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Carey, J.M. (2000). Parchment, equilibria, and institutions. Comparative Political Studies, 33(6/7), 735–761.

Carey, S.C. (2006). The dynamic relationship between protest and repression. Political Research Quarterly, 59(1), 1–11.

Carrubba, C.J. (2009). A model of the endogenous development of judicial institutions in federal and international systems. Journal of Politics, 71(1), 55–69.

Carter, D.B., & Signorino, C.S. (2010). Back to the future: modeling temporal dependence in binary data. Political Analysis, 18(3), 271–292.

Cederman, L.-E., Wimmer, A., & Min, B. (2010). Why do ethnic groups rebel? New data and analysis. World Politics, 62(1), 87–119.

Cheibub, J. (1998). Political regimes and the extractive capacity of governments: taxation in democracies and dictatorships. World Politics, 50(3), 349–376.

Cingranelli, D.L., & Filippov, M. (2010). Electoral rules and incentives to protect human rights. Journal of Politics, 72(1), 243–257.

Conrad, C.R., & Moore, W.H. (2010). What stops the torture? American Journal of Political Science, 54(2), 459–476.

Conrad, C.R., & Ritter, E.H. (2013). Tenure, treaties, and torture: the conflicting domestic effects of international law. Journal of Politics, 75(2), 397–409.

Cross, F.B. (1999). The relevance of law in human rights protection. International Review of Law and Economics, 19, 87–98.

Dai, X. (2005). Why comply? The domestic constitutency mechanism. International Organization, 59(2), 363–398.

Davenport, C. (1995). Multi-dimensional threat perception and state repression: an inquiry into why states apply negative sanctions. American Journal of Political Science, 39, 683–713.

Davenport, C. (2007a). State repression and political order. Annual Review of Political Science, 10, 1–23.

Davenport, C. (2007b). State repression and the domestic democratic peace. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dugan, L., & Chenoweth, E. (2012). Moving beyond deterrence: the effectiveness of raising the expected utility of abstaining from terrorism in Israel. American Sociological Review, 77(4), 597–624.

Earl, J., Soule, S.A., & McCarthy, J.D. (2003). Policing under fire? Explaining the policing of protest. American Sociological Review, 68(4), 581–606.

Fariss, C.J. (2014). Respect for human rights has improved over time: modeling the changing standard of accountability. American Political Science Review, 108(2), 297–318.

Finnemore, M., & Sikkink, K. (1998). International norms dynamics and political change. International Organization, 52(4), 887–917.

Francisco, R.A. (2004). After the massacre: mobilization in the wake of harsh repression. Mobilization: An International Quarterly, 9(2), 107–126.

Gartner, S.S., & Regan, P.M. (1996). Threat and repression: The non-linear relationship between government and opposition violence. Journal of Peace Research, 33(3), 273–287.

Gates, S. (2002). Recruitment and allegiance: the microfoundations of rebellion. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 46(1), 111–130.

Goemans, H.E., Gleditsch, K.S., & Chiozza, G. (2009). Introducing Archigos: a data set of political leaders. Journal of Peace Research, 46(2), 269–283. Data available at URL: http://mail.rochester.edu/~hgoemans/data.htm.

Grief, A., & Laitin, D.D. (2004). A theory of endogenous institutional change. American Political Science Review, 98(4), 14–48.

Grossman, H.I. (1991). A general equilibrium model of insurrections. American Economic Review, 81(4), 912–921.

Gurr, T.R. (1970). Why men rebel. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hafner-Burton, E.M. (2005). Trading human rights: how preferential trade agreements influence government repression. International Organization, 59, 593–629.

Hafner-Burton, E.M., & Tsutsui, K. (2005). Human rights in a globalizing world: the paradox of empty promises. American Journal of Sociology, 110(5), 1373–1411.

Hafner-Burton, E.M., & Tsutsui, K. (2007). Justice lost! The failure of international human rights law to matter where needed the most. Journal of Peace Research, 44(4), 207–425.

Hafner-Burton, E.M., Tsutsui, K., & Meyer, J.W. (2008). International human rights law and the politics of legitimation: repressive states and human rights treaties. International Sociology, 23(1), 115–141.

Hathaway, O.A. (2002). Do human rights treaties make a difference? Yale Law Journal, 111(8), 1935–2042.

Hathaway, O.A. (2003). The cost of commitment. Stanford Law Review, 55, 1821–1862.

Hathaway, O.A. (2007). Why do countries commit to human rights treaties? Journal of Conflict Resolution, 51(4), 588–621.

Heckman, J.J. (1979). Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica, 47(1), 153–161.

Helfer, L.R., & Voeten, E. (2014). International courts as agents of legal change: evidence from LGBT rights in Europe. International Organization, 68(1), 77–110.

Helmke, G. (2002). The logic of strategic defection: court-executive relations in argentina under dictatorship and democracy. American Political Science Review, 96 (2), 291–303.

Helmke, G. (2005). Courts under constraints. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hilbink, L. (2007). Judges beyond politics in democracy and dictatorship: lessons from Chile. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hill, D.W. (2010). Estimating the effects of human rights treaties on state behavior. Journal of Politics, 72(4), 1161–1174.

Hollyer, J.R., & Rosendorff, B.P. (2011). Why do authoritarian regimes sign the convention against torture? signaling, domestic politics, and non-compliance. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 6(3–4), 275–327.

Howard, R.M., & Carey, H.F. (2004). Is an independent judiciary necessary for democracy? Judicature, 87(6), 284.

Keck, M.E., & Sikkink, K. (1998). Activists beyond borders: advocacy networks in international politics. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Keith, L.C. (1999). The united nations international covenant on civil and political rights: does it make a difference in human rights behavior? Journal of Peace Research, 36(1), 95–118.

Keith, L.C. (2002). Judicial independence and human rights protection around the world. Judicature, 85(4), 195–201.

King, G., & Lowe, W. (2003). 10 million international dyadic events. Updated 2006. Downloaded 3, February 2008.

Klandermans, B. (1984). Mobilization and participation: social-psychological expansisons of resource mobilization theory. American Sociological Review, 49(5), 583–600.

Klandermans, B., & Oegema, D. (1987). Potentials, networks, motivations, and barriers: steps towards participation in social movements. American Sociological Review, 52(4), 519–531.

Kuran, T. (1991). Now out of never: the element of surprise in the east european revolution of 1989. World Politics, 44(1), 7–48.

Lichbach, M.I. (1987). Deterrence or escalation? The puzzle of aggregate studies of repression and dissent. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 31, 266–297.