Abstract

We study how work a schedule flexibility (flextime) affects happiness. We use a US General Social Survey (GSS) pooled dataset containing the Quality of Worklife and Work Orientations modules for 1998, 2002, 2006, 2010, and 2014. We retain only respondents who are either full-time or part-time employees on payrolls. For flextime to be associated with greater happiness, it has to be more than just sometimes flexible or slight input into one’s work schedule, that is, little flextime does not increase happiness. But substantial flextime has a large effect on happiness–the size effect is about as large as that of household income, or about as large as a one-step increase in self-reported health, such as up from good to excellent health. Our findings provide support for both public and organizational policies that would promote greater work schedule flexibility or control for employees.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Working conditions matter for our wellbeing–we spend about half of our waking life at work, and one of the critical attributes of our jobs is the flexibility it provides, which does affect greatly the other half of our waking life. Flexible working schedules or employee-centered flextime offers greater freedom and autonomy to conduct and navigate through our daily lives. Thus, we hypothesize, flextime will considerably improve one’s happiness.

Autonomy is not only a desire but arguably one of the basic human needs (Ryan and Deci 2000), and per livability theory (Veenhoven 2014), unfulfilled needs will make us unhappy. For instance, physicians complain that a lack of autonomy makes them unhappy (Lickerman 2012). A case example is a student, who worked at a gas station and experienced the polar opposite to having time autonomy (total flextime), and even worse than inflexible fixed work time–unpredictable and irregular working hours–and it made him very unhappy. Also, flexibility and autonomy should arguably promote intrinsic motivation among employees. Instilling intrinsic motivation and goals predict greater happiness (Schmuck et al. 2000; Roberts 2011).

Happiness is defined as “overall judgment of life that draws on two sources of information: cognitive comparison with standards of the good life (contentment) and affective information from how one feels most of the time (hedonic level of affect)” (Veenhoven 2008, p. 2). Happiness is reasonably precise, reliable, and valid measure, at least within-country or culture (Myers 2000; Oswald and Wu 2009; Diener et al. 2013). We follow usual practice in social indicators research and use terms “happiness” and “subjective wellbeing (swb)” interchangeably. Finally, to be clear, we focus here on general or overall happiness, not just a domain-specific happiness, such as job satisfaction.

There are only few studies regarding the relationship between work time flexibility and happiness. Bryson and MacKerron (2016) use smartphone data to study the context of work in the UK. Moen et al. (2016) study flexible schedules as workplace intervention.Footnote 1Golden et al. (2013) took an approach similar to ours, but we extend the previous work in several ways. First, we use more recent data for 2010 and 2014. Second, we add a key measure–the employee’s perceived input into their work schedule. Third, the prior research pertained mainly to the differences between hourly paid and salaried workers. Fourth, the estimation method includes more control variables, such as for workers’ region of residence. Finally, the present study situates the issue less in the literature of work-life and more in the philosophical conceptions of subjective wellbeing and work in a market society. An important limitation of earlier investigations is that they do not explain why flexibility should be associated with greater happiness, or why fixed work schedules should lead to unhappiness?

Wage Slavery and Commodification

“You are hired slaves instead of block slaves. You have to dread the idea of being unemployed and of being compelled to support your masters” (p. 283 Goldman et al. 2003).

Critics argue that under a system of capitalism, workers may be considered to be like “wage slaves,” at least in some important ways.Footnote 2 (Goldman et al. 2003; Stefan 2010) It is, to use Marcuse (2015) language, ’voluntary servitude’–it is voluntary because one can pick her master, it is servitude, because one has to have a master (unless one is a master or capitalist herself).

Esping-Andersen thinks of labor as of a commodity, and hence a notion of “commodification,” and its reverse “decommodification”– “labor is decommodified to the degree to which individuals or families can uphold a socially acceptable standard of living independent of market production”(1990, p 37).Footnote 3 Esping-Andersen goes on to argue that “the market becomes to the worker a prison within which it is imperative to behave as a commodity in order to survive” (1990, p. 36). Lane (2000) contends that markets are indifferent to the fate of individuals and that markets make people unhappy. Radcliff (2001) follows the thought: “I argue that the principal political determinant of subjective well-being is the extent to which a program of “emancipation” from the market is ’institutionalized’ within a state.”

It has been shown multiple times at the societal level that decommodification is associated with greater happiness (Lane 2000; Radcliff 2001; Pacek and Radcliff 2008a, b; Radcliff 2013; Okulicz-Kozaryn et al. 2014). Herein, we see flextime and setting one’s own work schedule as one step in the direction of emancipating one’s time from the vagaries of market, becoming more autonomous and free, thus, becoming less of a wage slave.

In addition, the quality of jobs more generally have been associated with both subjective and objective measures of wellbeing among those employed (Budd and Spencer 2015). This includes the role of working time as one of the important objective conditions of a job or work that contribute to a worker’s subjective wellbeing indicators, such as job or life satisfaction (Findlay et al. 2013). Employees’ level of subjective wellbeing, in turn, can feed back to work and the workplace productivity–thus, job and general life can be and has been improved by quality of work programs (Oswald et al. 2015).

Data and Method

We use the US General Social Survey (GSS) dataset containing two attached modules, the Quality of Worklife (QWL) and International Social Survey Program’s (ISSP) Work Orientations (WO). We pool data from 1998, 2002, 2006, 2010, and 2014. The GSS is a nationally representative sample collected from face-to-face interviews. We retain only respondents working full-time or part-time. The GSS contains a standard happiness question, which reads “Taken all together, how would you say things are these days–would you say that you are very happy, pretty happy, or not too happy?” and answers are coded as 1=”not too happy,” 2=”pretty happy,” and 3=”very happy.”Footnote 4. All variables are defined in Table 1. Distributions of all variables are shown in the Appendix in Fig. 1. Table 1 lists two measures of flexibility that come from the QWL, plus one measure from the WO survey (who set working hours). The typical controls used in the empirical literature regarding respondent happiness are then listed (Okulicz-Kozaryn 2016; Berry and Okulicz-Kozaryn 2011). One additional variable is included, the number of hours worked last week. It is important to distinguish between schedule flexibility and and the length of work hours. Perhaps, schedule flexibility is relatively more meaningful for the wellbeing of certain workers, such as those who also work long hours.

We also control for the important role for income–we use household income and not personal income because there are many more missing observations on personal income, and also one’s happiness is clearly affected by household income, at least indirectly, not only by personal income. Also, household income may matter more for the relationship between flexibility and one’s happiness–flexibility may contribute more to happiness if household income is low–one can save a lot of time and money with flextime: avoid traffic congestion, take advantage of off-peak pricing, manage care of children or elderly better, and coordinate work with other household members and responsibilities better than if schedules were fixed.

We add in a control for one’s self-rated level of health. There is some disagreement about the direction of causality, i.e., whether health predicts happiness or happiness predicts health (Diener 2015). The most recent evidence suggests that the health causing happiness is predominant (Liu et al. 2016), and we follow it here. We also postpone introduction of health variable to last step in model elaboration.

In addition to these variables, we also include two sets of dummy variables. The occupation dummies are based on ISCO classification of 1-digit occupations: professional, administrative/managerial, clerical, sales, service, agriculture, production, transport, craft, and technical. Occupation dummies are important to control for because there are differences across occupations in working conditions that could affect happiness, and there are differences in flexibility across occupations. We seek to pick up the direct influence of flexible work scheduling, controlling for the other specific aspects of occupations. We also include twelve regional dummies (census regions) to control for potential place or cultural differences in work or wellbeing: New England, Middle Atlantic, E. Nor. Central, W. Nor. Central, South Atlantic, E. Sou. Central, W. Sou. Central, Mountain, and Pacific.

We use OLS estimation, which Ferrer-i-Carbonell and Frijters (2004) showed will yield substantially the same results with those from discrete models, and indeed, OLS became the norm in the literature measuring associations with happiness (Blanchflower and Oswald 2011).

Results

Results for each of the three measures of flexibility are presented in a separate table, and each table contains four models. The first model is bivariate. The second model sequentially adds family income, reflecting a clearly important characteristic of jobs or households that influences a worker’s happiness. The third column adds socio-demographic variables known to predict happiness, and the occupation and region dummies. The last, fourth column, adds health and number of hours worked last week, another key characteristic of one’s job–these two variables are added at the very end because they have many missing observations.

Table 2 shows results for who set working hours (i.e. schedules). The base case is the middle category ’i decide w/limts.’ It turns out that such limited flexibility is no more significantly associated with happiness than having no flexibility or discretion at all (’employer decides’). Full flexibility (’free to decide’), on the other hand, is associated with considerable happiness in column a1. Although elaboration of the model in subsequent columns attenuated somewhat the effect of flexibility, its effect persists despite all control variables included. In fact, only schedule flexibility, married, and health variables remain significant in the full model. Also, note that the size effect is as much as half that of being married (.13 v .27), and about as big as one step on 4-step health scale (.15), for instance, having control over one’s work schedule contributes as much to happiness as having one’s health go from “good” to “excellent.” Thus, the effect of having discretion into one’s work schedule is salient and meaningful.

The other two flexibility variables are available for multiple years in the QWL: 2002, 2006, 2010, and 2014. Table 3 shows results for can change schedule (start and end times of work). The base case is the lowest category ‘never’. As in Table 2, where there was no difference between the two lowest categories ‘employer decides’ and ‘i decide w/limits’, ‘rarely’ is no different from ‘never.’ Having flexibility only on rare occasion yields no difference in terms of happiness. An ability to change one’s daily schedule ‘often’, on the other hand, is associated with markedly greater happiness. The positive impact of ‘often’ remains robust, with all controls included, although its size effect is a bit muted.

Finally, Table 4 shows results for not hard to take time off. Again, the base is the lowest category ‘very hard’, and again, there is no difference between second lowest category ‘somewhat hard’ and the base. The most flexible category ‘not at all hard’ is not only very significant statistically, but also substantially.

The Appendix contains beta coefficients that confirm that schedule flexibility has a strong positive association with happiness, indeed, about as strong as the effect of income, and about one fourth of the size effect of health. The effect of having considerable frequency or ease of schedule flexibility is large and thus unambiguously positive, given that controlling for occupation would capture most other contributing working conditions—arguably larger than what most people would expect vis-à-vis other contributors to happiness.

Discussion

Almost 100 years ago, Keynes ([1930] 1963) envisioned the future for grandchildren of his generation who thanks to continued economic growth would finally enjoy the fruits of painful laboring for centuries. Keynes envisioned more leisure and enjoyment. This has not (yet) transpired in most countries. It is debated whether the average length of working hours is in general declining, or just for certain subsets of workers–in particular, those who are not salaried (Golden and Figart 2000)–but actually we do now devote more hours to labor than before industrial revolution (Schor 2008). Moreover, average real wage rates have stagnated over the past half acentury despite agrowing rate of labor productivity (Bivens and Mishel 2015). Societal happiness does not depend on economic growth (Easterlin et al. 2010), but rather depends on growth in wage rates (Fischer 2008). Another explanation of Easterlin paradox may be “wage slavery.” As Marcuse put it (2015):

“Happiness,” said Freud, “is no cultural value.” Happiness must be subordinated to the discipline of work as full-time occupation, to the discipline of monogamic reproduction.

One key working condition, having discretion or more control over one’s work schedule, such as with daily flextime, arguably may serve to lessen the degree of exploitation of labor resulting from longer hours for no greater real wage level. Indeed, the ability to control the timing of work, with full flextime, improves not only individuals’ subjective wellbeing, but moves a society towards a more humanistic civilization for which philosophers, social theorists, and intellectuals have been advocating for decades (Fromm 1944, 1962, 1964, [1941] 1994; Marcuse 2015; Maslow 2013; Harvey 2014).

Similar although earlier and more limited GSS and Quality of Worklife datasets were used to study the relationship between happiness and the other dimensions of working hours, such as their length (Golden and Okulicz-Kozaryn 2015), involuntary nature of extra working hours (Golden and Wiens-Tuers 2006), and a focus on outcomes other than happiness, such as work-family conflict (Golden et al. 2011). Moreover, the present paper controls for the influence of number of work hours and focuses on the isolated role of flexible work schedules, including a question from a second data source reflecting workers’ decision input into their work schedules. By focusing on flexibility and happiness, it is thus a contribution that is differentiated from the vast empirical literature on hours mismatches or long hours and health (e.g., Costa et al. 2006; Dembe et al. 2008; Beckers et al. 2008; Kleiner and Pavalko 2010; Bell et al. 2012; Başlevent and Kirmanoğlu 2014) including one using the 2002 GSS data (Grosch et al. 2006), association of hours and happiness (Rätzel 2009) or other aspects of wellbeing (Wooden et al. 2009; Wunder and Heineck 2013) and the association of flexibility and work-life balance (e.g., Lyness et al. 2012; Golden et al. 2016).

The usual caveat is that, without experimental data, causality is difficult if not impossible to establish, but real experiments are almost never possible and quasi-experiments are often inadequate to ensure causality as well. We would argue that one’s work schedule is often quite exogenously determined–few people have the luxury of picking among many jobs or their conditions, or their precise daily work schedule with their jobs. Rather, jobs and their schedule characteristics are mostly given, and presented as a take-it-or-leave it choice for applicants and incumbent workers. Thus, we can safely assume that the direction of causality runs from schedule flexibility to happiness, although we may not entirely rule out that happier workers self-select (in the longer run) into jobs featuring more schedule flexibility (this would be testable with panel data, which controls for the individuals’ pre-existing level of happiness). It is unlikely, however, even in the long run, that most happy people would end up in flexible jobs and unhappy people in inflexible jobs, particularly as some kind of discretionary choice. If anything, there is more risk of unobserved characteristics that may affect both jobs and happiness, such as personality attributes. That is arguably a key potential limitation–certain personalities (e.g., extroverts) may be more likely than others (e.g., introverts) to end up in occupations with flexible scheduling opportunities. Personality traits and other potential confounders are likely to be relatively stable over time, and hence, use of panel data with observations on pre-existing personality traits should help to alleviate this problem. However, as of now, there is no long running panel for the US containing happiness, schedule flexibility, and personality items.Footnote 5

That one working condition, having a great deal of work schedule flexibility matters as much as income or as much as quarter of the effect of one’s health is arguably larger than in the common wisdom. This is thus a new area ripe for additional happiness research–to point to surprising or nonintuitive findings so that irrational human beings (Ariely 2009) can make better informed choices, choices that will make them happy.

In terms of public policy, our results support contemporary modifications of the basic US Fair Labor Standards Act workweek rules, as well as, workplace and organizational flexibility practices generally. In particular, employers can improve employees happiness with a more advanced human resource management of providing system more frequent discretion of when employees engage in work activity. In addition, public policy makers could institute an individual worker “right to request” a change in the timing (and number) of their work hours and time off, protected from retaliation from making such requests, and be granted that request unless there is a clear business disruption–the result would likely be happier workers, firms no worse off, and perhaps better productivity or performance.

Notes

Moen et al. (2016) differ from our study considerably and while not strictly comparable, their similar results using a stronger life-course longitudinal research design, indirectly instill confidence in our cross-sectional findings.

If the comparison strikes you as far-fetched or unfounded let us provide anecdotal evidence. “It is basically slave labor” said one discontented Brit, whose opinion is more or less representative of large class of people–strikingly, 60% of Brits identify themselves as working class (Higgins 2016). Being an assistant professor (AOK) I only make about a median wage, and I caught myself calling my rich corporate friends “slaves”: they are rich, but not free: they have to do as capitalist pleases. I, on the other hand, can write whatever I like and whenever I want (I only have to be at work twice a week for three hours to teach). Though, Marx himself makes a distinction between wage-labor and slave-labor ([1867] 2010).

Measures of decommodification tend to focus on welfare programs: pensions, sickness benefits, and unemployment compensation. For instance, one such measure “encompasses three primary dimensions of the underlying concept: the ease of access to welfare benefits, their income-replacement values, and the expansiveness of coverage across different statuses and circumstances”. Pacek and Radcliff (2008b, p. 183). We think that not only welfare programs, but also job characteristics, such as flextime, affect degree of commodification of labor.

This question has been used in multitude of happiness studies (e.g., Blanchflower and Oswald 2003; Oishi et al. 2011; Okulicz-Kozaryn 2016; Berry and Okulicz-Kozaryn 2011). For more see http://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&q=happiness+general+social+survey

German SOEP and British HPS may have the required data for Europe. American PSID has started happiness question only recently, and AddHealth contains mostly data about adolescents, but as more waves become available, PSID and AddHealth could be potentially used to replicate and extend the present study.

References

Ariely, D. (2009). Predictably irrational revised and expanded edition: The hidden forces that shape our decisions. New York: Harper.

Baṡlevent, C., & Kirmanoġlu, H. (2014). The impact of deviations from desired hours of work on the life satisfaction of employees. Social Indicators Research, 118, 33–43.

Beckers, D.G., van der Linden, D., Smulders, P.G., Kompier, M.A., Taris, T.W., & Geurts, S.A. (2008). Voluntary or involuntary? Control over overtime and rewards for overtime in relation to fatigue and work satisfaction. Work & Stress, 22, 33–50.

Bell, D., Otterbach, S., & Sousa-Poza, A. (2012). Work hours constraints and health. Annals of Economics and Statistics/Annales DÉ,Conomie Et De Statistique, 35–54.

Berry, B.J., & Okulicz-Kozaryn, A. (2011). An Urban-Rural happiness gradient. Urban Geography, 32, 871–883.

Bivens, J., & Mishel, L. (2015). Understanding the Historic Divergence between Productivity and a Typical Worker–s Pay: Why It Matters and Why It–s Real. Economic Policy Institute, Washington DC. http://www.epi.org/publication/understanding-the-historic-divergence-betweenproductivity-and-a-typical-workers-pay-why-it-matters-and-why-its-real.

Blanchflower, D., & Oswald, A. (2003). Does Inequality Reduce Happiness? Evidence from the States of the USA from the 1970s to the 1990s. Mimeographed, Warwick University.

Blanchflower, D.G., & Oswald, A.J. (2011). International happiness: a new view on the measure of performance. The Academy of Management Perspectives, 25, 6–22.

Bryson, A., & MacKerron, G. (2016). Are you happy while you work?. The Economic Journal.

Budd, J.W., & Spencer, D.A. (2015). Worker well-being and the importance of work: bridging the gap. European Journal of Industrial Relations, 21, 181–196.

Costa, G., Sartori, S., & Åkerstedt, T. (2006). Influence of flexibility and variability of working hours on health and well-being. Chronobiology international, 23, 1125–1137.

Dembe, A.E., Delbos, R., & Erickson, J.B. (2008). The effect of occupation and industry on the injury risks from demanding work schedules. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 50, 1185–1194.

Diener, E. (2015). Advances in the Science of Subjective Well-Being. 2015 ISQOLS Keynote.

Diener, E., Inglehart, R., & Tay, L. (2013). Theory and validity of life satisfaction scales. Social Indicators Research, 112, 497–527.

Easterlin, R.A., McVey, L.A., Switek, M., Sawangfa, O., & Zweig, J.S. (2010). The happiness–income paradox revisited. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107, 22463–22468.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Polity Pr,

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A., & Frijters, P. (2004). How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of happiness?. Economic Journal, 114, 641–659.

Findlay, P., Kalleberg, A.L., & Warhurst, C. (2013). The challenge of job quality. Human Relations, 66, 441–451.

Fischer, C.S. (2008). What wealth-happiness paradox? A short note on the American case. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, 219–226.

Fromm, E. (1944). Individual and social origins of neurosis. American Sociological Review, 9, 380–384.

Fromm, E. (1962). Beyond the chains of illusion: My encounter with Marx and Freud. Continuum International Publishing Group.

Fromm, E. (1964). The heart of man: Its genius for good and evil Vol. 12. Abingdon-on-Thames: Taylor & Francis.

Fromm, E. (1994). Escape from freedom. New York: Holt Paperbacks.

Golden, L., Chung, H., & Sweet, S. (2016). Positive and Negative Application of Flexible Working Time Arrangements: Comparing the United States and the EU Countries, SSRN.

Golden, L., & Figart, D. (2000). Doing something about long hours. Challenge, 43, 15–37.

Golden, L., Henly, J.R., & Lambert, S. (2013). Work schedule flexibility: a contributor to happiness?. Journal of Social Research and Policy, 4, 107.

Golden, L., & Okulicz-Kozaryn, A. (2015). Work Hours and worker happiness in the US: Weekly Hours, Hours Preferences and Schedule Flexibility, SSRN.

Golden, L., & Wiens-Tuers, B. (2006). To your happiness? Extra hours of labor supply and worker well-being). The Journal of Socio-Economics, 35, 382–397.

Golden, L., Wiens-Tuers, B., Lambert, S.J., & Henly, J.R. (2011). 10 Working Time in the employment relationship: working time, perceived control and work–life balance. Research Handbook on the Future of Work and Employment Relations, 188.

Goldman, E., Falk, C., Pateman, B., & Moran, J. M. (2003). Emma Goldman: Made for America. (Vol. 1, pp. 1890–1901). Univ of California Press.

Grosch, J.W., Caruso, C.C., Rosa, R.R., & Sauter, S.L. (2006). Long hours of work in the US: associations with demographic and organizational characteristics, psychosocial working conditions, and health. American journal of industrial medicine, 49, 943–952.

Harvey, D. (2014). Seventeen contradictions and the end of capitalism. New York NY: Oxford University Press.

Higgins, A. (2016). Wigan’s Road to ‘Brexit’: Anger, Loss and Class Resentments. New York: The New York Times.

Jacoby, W.G. (2005). Regression iii: Advanced methods. Department of Political Science Michigan State University.

Keynes, J.M. (1963). Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren. New York NY: WW Norton and Company.

Kleiner, S., & Pavalko, E.K. (2010). Clocking in: The organization of work time and health in the United States. Social Forces, 88, 1463–1486.

Lane, R.E. (2000). The loss of happiness in market democracies. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Lickerman, A. (2012). The Desire for Autonomy, Psychology Today.

Liu, B., Floud, S., Pirie, K., Green, J., Peto, R., Beral, V., Collaborators, M.W.S., et al. (2016). Does happiness itself directly affect mortality? The prospective UK Million Women Study. The Lancet, 387, 874–881.

Lyness, K.S., Gornick, J.C., Stone, P., & Grotto, A.R. (2012). It–s all about control: Worker control over schedule and hours in cross-national context. American Sociological Review, 77, 1023–1049.

Marcuse, H. (2015). Eros and civilization: A philosophical inquiry into Freud. Boston: Beacon Press.

Marx, K. (2010). Capital, vol. 1. http://www.marxists.org.

Maslow, A.H. (2013). Toward a psychology of being. New York: Start Publishing LLC.

Moen, P., Kelly, E.L., Fan, W., Lee, S.-R., Almeida, D., Kossek, E.E., & Buxton, O.M. (2016). Does a flexibility/ support organizational initiative improve high-tech employees– well-being? Evidence from the work, family, and health network. American Sociological Review, 134–164.

Myers, D.G. (2000). The funds, friends, and faith of happy people. American Psychologist, 55, 56–67.

Oishi, S., Kesebir, S., & Diener, E. (2011). Income inequality and happiness. Psychological Science, 22, 1095–1100.

Okulicz-Kozaryn, A. (2016). Unhappy metropolis (when American city is too big), Cities.

Okulicz-Kozaryn, A., Holmes, IVO., & Avery, D.R. (2014). The subjective Well-Being political paradox: Happy welfare states and unhappy liberals. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99, 1300–1308.

Oswald, A.J., Proto, E., & Sgroi, D. (2015). Happiness and productivity. Journal of Labor Economics, 33, 789–822.

Oswald, A.J., & Wu, S. (2009). Objective confirmation of subjective measures of human Well-Being: Evidence from the U.S.A. Science, 327, 576–579.

Pacek, A., & Radcliff, B. (2008a). Assessing the welfare state: The politics of happiness. Perspectives on Politics, 6, 267–277.

Pacek, A., & Radcliff, B. (2008b). Welfare policy and subjective Well-Being across nations: an Individual-Level assessment. Social Indicators Research, 89, 179–191.

Radcliff, B. (2001). Politics, markets, and life satisfaction: The political economy of human happiness. American Political Science Review, 95, 939–952.

Radcliff, B. (2013). The political economy of human happiness: How voters’ choices determine the quality of life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rätzel, S. (2009). “Revisiting the neoclassical theory of labour supply–Disutility of labour, working hours, and happiness, Tech. rep. Otto-von-Guericke University Magdeburg, Faculty of Economics and Management.

Roberts, J.A. (2011). Shiny Objects: Why We Spend Money We Don’t Have In Search Of Happiness We Can’t Buy. San Francisco: HarperOne.

Ryan, R.M., & Deci, E.L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary educational psychology, 25, 54–67.

Schmuck, P., Kasser, T., & Ryan, R.M. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic goals: Their structure and relationship to well-being in German and US college students. Social Indicators Research, 50, 225–241.

Schor, J. (2008). The overworked American: The unexpected decline of leisure. New York: Basic books.

Stefan (2010). Are You a Wage Slave? Socialist Standard.

Veenhoven, R. (2008). Sociological theories of subjective well-being. In Eid, M., & Larsen, R. (Eds.), The Science of Subjective Well-being: A tribute to Ed Diener (pp. 44–61). New York: The Guilford Press.

Veenhoven, R. (2014). Livability theory. Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research, 3645–3647.

Williams, R. (2016). Supplemental Notes on Standardized Coefficients. Department of Sociology. University of Notre Dame.

Wooden, M., Warren, D., & Drago, R. (2009). Working time mismatch and subjective well-being. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 47, 147–179.

Wunder, C., & Heineck, G. (2013). Working time preferences, hours mismatch and well-being of couples: Are there spillovers?. Labour Economics, 24, 244–252.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

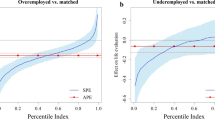

Finally, let’s compare effects in terms of effect sizes in Table 5, which repeats columns 3 and 4 from the tables in the body of the paper but reports beta (standardized) coefficients. They all have similar value ≈.05 in full specification (original column 4), except the highest category on not hard to take time off, ‘not at all hard’ (v ‘very hard’) is about twice as big at .12. Perhaps, this is the key feature of schedule flexibility that workers need: they are happy to have more or less fixed schedules as long as it is very easy to take time off.

Comparing these values to income reveals that they are about as big as income or larger, and about as statistically significant or more significant. Again, one caveat to keep in mind is that this study uses household income, not personal income. Still, the size effect is quite striking. Again, as argued in the body of the paper, the schedule flexibility effect is about fourth of health effect, and considering health as one of the strongest, if not the strongest predictors of happiness, it is again a large effect.

Standardizing dummy variables results in somewhat meaningless quantities (e.g., Jacoby 2005; Williams 2016). Hence we use schedule flexibility measures as ordinal in Table 6 and standardize them. Results are substantively the same except in case of who set working hours, which became insignificant.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Okulicz-Kozaryn, A., Golden, L. Happiness is Flextime. Applied Research Quality Life 13, 355–369 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-017-9525-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-017-9525-8