Abstract

Not being able to combine work with family properly is negatively related to employees’ quality of life. Some firms are aware of this reality and provide their employees family-friendly practices, a set of practices designed to enable employees a work–family balance. Family-friendly practices are classified in three subsets: family support practices, flexible arrangement practices, and parental leave practices. Then, this paper analyzes the impact of different subsets of family-friendly practices on work–family balance for women and men subsamples, as well as to disentangle the mechanisms through with such effects occur. Based on a representative sample of 8,061 Spanish workers and using the Baron and Kenny procedure to test for mediation, the results show that the three subsets of family-friendly practices increase work–family balance for both genders, although some of them have different effects for women and men. In line with societal gender role expectation, family support practices better accommodate men’s need, increasing work–family balance almost for them, and parental leave practices women’s need, increasing work–family balance more for them. However, flexible arrangement practices increase work–family balance equally for both genders. Moreover, in all cases, the effect of family-friendly practices on work–family balance goes beyond the effect of time outside work and time at work, then this partial mediation indicates that time is an important mechanism in achieving work–family balance. In sum, offering employees family-friendly practices is a good starting point in order to increase people’s quality of life by helping them achieve work–family balance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Family and work interface are two important spheres that can influence subjective perceptions of employees’ quality of life (Rice et al. 1992; Greenhaus et al. 2003; McMillan et al. 2011; De Simone et al. 2014). The increase in the number of women in paid employment and the transition to dual-earner families have increased the likelihood that both men and women will have family and work responsibilities (Allen et al. 2000) in most developed countries. The perspective that has dominated the research in work–family interference is the conflict approach. Work–family conflict is defined as “a form of interrole conflict in which the role pressure from the work and family domains are mutually incompatible in some respects” (Greenhaus and Beutell 1985, p. 77). In that respect, there are researches that demonstrate that not being able to combine work with family properly is negatively related to quality of life (Md-Sidin et al. 2008), life satisfaction (De Simone et al. 2014; Rode et al. 2007), and well-being (Milkie and Peltola 1999; Voydanoff 2005). However, more recently, several researchers have called for a more positive approach to the work–family interface by examining the benefits of multiple role membership (Grzywacz and Butler 2005; McMillan et al. 2011; Parasuraman and Greenhaus 2002). In this vein, work–family balance is defined as (Grzywacz and Carlson 2007, p. 458) “the accomplishment of role-related expectations that are negotiated and shared between and individual and his or her role-related partners in work and family domains.” Some reasons that explain how work–family balance enhances an individual’s quality of life are (Greenhaus et al. 2003) the buffering effect that commitment to multiple roles may have against negative experiences in one of them (Barnett and Hyde 2001) or that satisfaction in one domain may also lead to satisfaction in the other (Xu 2009).

Some firms are aware of this reality and provide their employees a set of practices named family-friendly practices that enable employees to combine family and work commitments and, therefore, enhance multiple role identities (Glass and Finley 2002; Sirgy et al. 2008). From a theoretical point of view, family-friendly practices affect life satisfaction by reducing work–family conflict or increasing work–family balance. Also, family-friendly practices facilitate the employment of women, increasing gender equality (Voicu et al. 2009), and contributing to the social approach of quality of life (Łapniewska 2014).

Although theoretically family-friendly practices are offered by firms to improve employees’ work–family balance, the real motivations to offer them may be less altruistic. In that respect, some firms consider these practices like a “necessary evil” of doing business (McMillan et al. 2011), a consequence of employees and society pressures. Other firms seek to be considered like progressive firms and offer the practices to attract and retain a dedicated workforce that, within today’s turbulent work environment (Rau and Hyland 2002; Williams et al. 2000), may lead to increase organizational performance (Beauregard et al. 2009). However, there is little research that considers the effect of family-friendly practices on work–family balance (Frye and Breaugh 2004), and the results obtained have been somewhat debatable (Brough et al. 2008). In words of Hyman and Summers (2004), it seems that family-friendly practices are introduced primarily to meet business needs, rather than those of employees.

The present article aims to contribute to our understanding of the impact of family-friendly practices on work–family balance. Family-friendly practices can be classified into three broad subsets (Ferrer and Gagné 2006; Glass and Finley 2002): family support practices, flexible arrangement practices, and parental leave practices. Family support practices include a set of services that employers make available to workers, such as nurseries and canteens, so that they can better meet their obligations within the company. Flexible arrangement practices include all policies giving workers greater flexibility in terms of working time and place. And finally, parental leave practices are all practices that reduce working hours to provide time for family care-giving. All these practices seek to contribute to work–family balance, but they can do it in a different way. The main objective of the paper is to study the impact of each subset of family-friendly practices on work–family balance analyzing the differences between women and men. Our premise is that the impact of the practices will be different in both genders because societal expectations about gender roles are different (Carlson and Frone 2003; Hill 2005). We also analyze the mechanisms by which family-friendly practices affect employees’ work–family balance, taking time outside work satisfaction and time at work as mediator variables

The hypotheses were tested using a representative sample of 8,061 Spanish workers. Most of the existing evidence on the consequences of family-friendly practices for employees, particularly on work–family balance, has been obtained from samples in English-speaking countries (Idrovo et al. 2012). However, the direct comparison of the consequences of the various types of work–life balance policies was difficult due to cross-cultural variation in government regimes, employment policies, and labor market conditions, and, as a result, the effectiveness of these policies may depend on the countries’ cultural contexts (Brough et al. 2008). It is also worth noting that the information about family-friendly practices was provided by the employees and hence captured what employees perceived and used rather than what employers declared to be the case.

The Spanish Context Concerning Work–Family Balance

Spain is one of the countries mapped on the most-gender traditional area regarding labor–gender configuration and family-friendly development (Bosch and Wagner 2003). However, it shares a lot of characteristics with other European developed countries. Concretely, according to several classifications that take into account cultural values, Spain is classified with other European countries in the Latin or Mediterranean cluster (Esping-Andersen 1990; Northouse 2007). Those countries are characterized by low gender egalitarianism, low future orientation, high in-group collectivism, and high power distance (Jesuino 2002). Moreover, Spain shares a lot of characteristics in terms of gender ideology, social changes, and work-related characteristics with other Spanish-speaking countries (Arriagada 2002; Idrovo et al. 2012; World Bank 2011).

In all these countries, views about the relationship between work and family have evolved over the years, just as the role of women in the labor market has changed. The early view was the separate sphere pattern. This pattern considered work and family as separate spheres of social life, independent from each other and not affected mutually (Edwards and Rothbard 2000; Lambert 1990). According to this view, men were associated with work, whereas women were associated with family (Fletcher 2005), and in order to function properly, these two spheres needed to remain separate. In Spain, this view fits perfectly in Franco’s regime, where the people lived within a dictatorship and where women’s rights were completely diminished (Nuño 2008).

By the 1970s, researchers started to consider family and work as an open system with some interdependence (Clark 2000; Katz and Kahn 1978), primarily as a consequence of the introduction of women into the labor market in most industrial societies. In Spain, similar to what has happened in other southern European countries (Rodríguez-Nuño 2006) and in Latin American countries (World Bank 2011), the female activity rate rose from 38.5 % in 1996 to 52.65 % in 2010, whereas the male activity rate has been very stable, shifting only from 66.1 % in 1996 to 67.7 % in 2010 (Encuesta de Población Activa 2010). However, social values relating to the roles of men and women in the family have not changed as quickly as the rate of women’s employment (Arriagada 2002; Silván-Ferrero and Bustillos 2007). Spain continues to be a country with a masculine culture in which differences in gender roles are heightened, a culture that strongly favors that women with children should stay at home (Treas and Widmer 2000). In this line, Rodríguez and Fernández (2010), in a research drawing on discussion groups consisting of Spanish couples, concluded that women who worked outside of the home found it more difficult to balance work and family life.

But in recent years, greater importance is being attributed in Spanish society to the balance between family life and work (Chinchilla et al. 2010; OECD 2007; Poelmans 2008). Spain has experienced profound change in the development of measures that have helped employees balance work and family. The government has begun to take responsibility for this issue by creating the Law on Reconciliation of Work and Family life for working people (Law 39/1999). This law, which aims to foster the inclusion of women in the labor market with equal conditions to men, added European directives on maternity and paternity leave and part time work to Spanish legislation. After this law, a number of legislative measures have dealt with aspects of work–family balance, such as the Law for Promotion of Personal Autonomy and Care of Dependent Persons (Law 39/2006) and the Law for Effective Equality between Men and Women (Law 3/2007). Besides, new institutions have been founded, such as the Ministry of Equality in 2008, to enact policies in the area of equality law and laws against domestic violence. However, Spanish expenditure on family-friendly policies is one of the lowest in European countries (Esping-Andersen 1999; Poelmans et al. 2003).

Another important change that occurred during the last years is the involvement of firms in the work–family balance of individuals. During recent years, the implementation of family-friendly practices across firms has been extended in European countries, among them Spain (Jokinen and Kuronen 2011), as well as in Latin American countries (Idrovo et al. 2012). A study by Chinchilla et al. (2003) with data from the IESE Business School 2002 Family Responsible Employer Index concerning about 150 Spanish firms showed, in relation to family support practices, that 31.4 % of Spanish firms surveyed offered employees a canteen and that none of them had nursery services inside the firm. However, 13.3 % of those firms offered information about nursery services, and 4.7 % offered some kind of economic benefits to pay for them. Regarding flexible arrangement practices, the study showed that 59 % of Spanish firms surveyed offered their employees flexible work time, 60 % offered the possibility of working part time, and 21 % offered work from home. Finally, for parental leave practices, the study revealed that around 85 % of firms offered employees the possibility of taking time off for personal reasons.

Family-Friendly Practices and Work–Family Balance

While the main aim of family-friendly practices is to help employees to achieve a greater work–family balance, the real effect has been somewhat open to question (Brough et al. 2008; Frye and Breaugh 2004). On the one hand, some previous studies, like those of Frone et al. (1997) and Dancaster (2006), showed that flexible work arrangement practices and parental leave practices promoted work–family balance, using data from Canadian and South African employees, respectively. Moreover, using data about civilian US labor force, Voydanoff (2004) found that family-friendly practices increased work–family balance. Also, Hill et al. (2001), using data from US employees at International Business Machines (IBM), showed that perceived flexibility was strongly and positively correlated with work–family balance. In this line, an Australian research project has found that 70 % of firms that used teleworking reported an increase in work–family balance (Australian Telework Advisory Committee 2006). On the other hand, some studies have not found the expected results. For instance, contrary to their own expectations, Batt and Valcour (2003) based on data relating to employees in New York found that flexible schedule policies did not have an impact on work–family conflict. Moreover, other studies, like that of O’Driscoll et al. (2007) using Australian data, have found that family-friendly practices contribute to reinforcing the traditional model of division of work and contribute to increased work–life conflict.

One explanation to account for the lack of consensus about the effect of family-friendly practices on work–family balance may be that most of the existing research has examined the effect of family-friendly practices without taking into account the different subsets of practices and without differentiating between men and women (Hill 2005), who experience different levels of work–family conflict (Becker and Moen 1999; Duxbury and Higgins 1991).

With respect to the differences between men and women, it is generally assumed that there are differences in the societal gender role expectations about women and men roles. Men are traditionally associated with work, whereas women are associated with family (Fletcher 2005). These expectations neatly match the views of both women and men as regards their own roles (Carlson and Frone 2003): women have a tendency to be more highly involved in family roles and tend to be less flexible in responding to the demands of work, whereas men have a tendency to be more highly involved in work roles and are less flexible as regards family obligations. In the case of Spanish men, the reality confirms that they have not compensated for the increase in female employment through a corresponding increase in household work, so that women continue to be those in charge of most household work in heterosexual dual-earner couples (Álvarez and Miles 2003; Goñi-Legaz et al. 2010; Sánchez-Herrero et al. 2009; Sevilla-Sanz 2010). In this line, some researchers have pointed out that men and women differ in how they manage the boundaries between family and work and that they have different preferences for integration or segmentation of work and family domains (Andrews and Bailyn 1993; Ashforth et al. 2000; Edwards and Rothbard 2000). Segmentation means that a person separates work and non-work time and that one sphere of life does not influence the other, whereas integration means that a person combines the roles s/he can work in both spheres at the same time, which results in a mutually reinforcing performance.

The different practices are designed to increase work–family balance of workers, but they do it in different ways. Family support practices sought to maintain the traditional vision of the ideal employee, that is, someone working full time, who is committed to his or her work and has no outside responsibilities (Fursman and Callister 2009). However, flexible arrangement practices and parental leave practices endeavor to facilitate work–family integration (Clark 2000), enabling people to cope with the fluctuating demands of home life. Thus, taking into account that Spanish men are more involved in their work role than in their family role, family support practices better accommodate men’s needs than women’s needs. Moreover, as Spanish women seek to balance the competing needs of family and work, while maintaining their responsibilities at home, they would value practices that help them to integrate work and family instead of segment them. In this sense, flexible arrangements and parental leave practices enable women to have more control over time and spaces and to integrate work and family, thus comprising practices that better suit their needs.

-

H1a

Family support practices increase work–family balance more for men than for women.

-

H1b

Flexible arrangement practices increase work–family balance more for women than for men.

-

H1c

Parental leave practices increase work–family balance more for women than for men.

Disentangling the Process: Mediator Variables

The mechanisms by which family-friendly practices affect employees’ work–family balance remain under-researched (Allen 2001). It is generally assumed that the main problems that individuals face in reconciling family and work domains are the need to fulfill the different roles required by the responsibilities of both spheres and the problems that arise as a consequence of limitations on time (McMillan et al. 2011). This is reflected in the definition of work–family balance offered by Greenhaus et al. (2003), which states that work–family balance must contain three components: time balance (time dedicated equitably to work and family responsibilities), involvement balance (equitable psychological involvement in work and family roles), and satisfaction balance (the equitable satisfaction level that individuals get from work and family responsibilities).

Time is a fixed resource that must be divided into work and outside work responsibilities. Previous literature has found that the number of working hours has a negative impact on work–family balance. For example, Valcour (2007), using a sample of telephone call center representatives from the USA, found that working hours decrease work–family balance. Also from the USA, Frone et al. (1997) found that the number of working hours has a positive effect on work–family conflict. The same result has been found by Foley et al. (2005) and by Balmforth and Gardner (2006) using a sample from Hong Kong and New Zealand, respectively. Besides, the more hours and the more involvement spent in one role, the lower work–family balance is (Edwards and Rothbard 2000). This has been found for example by Rothbard (2001) using a sample of employees at a large public university from the USA.

In this paper, considering the data available, we will study how time outside work satisfaction and time at work will explain the indirect influence that each one of the subsets of family-friendly practices has on work–family balance.

Family Support Practices

Family support practices can help employees to attain work–family balance by reducing the number of household commitments that individuals have and the resulting time and involvement needed for the family domain (Chinchilla et al. 2003), in line with the Voydanoff (2005). This model focused on demands, resources, and strategies that were presumed to be associated with work–family balance, including family-friendly practices such as boundary-spanning resources that directly addressed how the work and family domain connected with each other. In line with this model, family support practices give additional resources to employees to accomplish family responsibilities, which results in a higher level of satisfaction with the family domain. So, these policies aim to increase work–life balance by offering employees support solutions to help them take care of their dependents while maintaining a high level of productivity at work.

-

H2a

Time outside work satisfaction mediates the influence of family support practices on work–family balance, so workers with family support practices have more time outside work satisfaction, and this increase results in higher levels of work–family balance.

Flexible Arrangement Practices

People’s needs do not have a strict timetable each day, nor are they always the same (Chinchilla et al. 2003). Therefore, people need flexibility and control to accomplish both demands so as to gain work–family balance. Clark’s border theory (2000) can help to explain how the practices accomplish this objective. Clark defines a border as a line of demarcation between domains, defining the point at which domain relevant behavior begins or ends. Borders may be physical, temporal, and psychological. Flexible arrangement practices are practices that change the border of the organization and aim to offer alternative formulas of flexibility at work, in terms of both time and space (Clark 2000).

Moreover, flexible arrangement practices can invoke the principle of reciprocity. Employees work harder during their time at work in exchange for the ability to tailor their work hours to meet their needs outside work, reducing the number of working hours. According to this principle, flexibility decreases the number of working hours and increases the number of hours that employees can stay at home. This result has been found in previous literature, for example by Gray and Tudball (2002) and by Wolcott and Glezer (1995) both using data from Australia. Moreover, if employees have more control over their timetable, the levels of satisfaction with their family life will increase (Brough et al. 2005). Therefore, it would be interesting to know whether flexible arrangement practices have a direct effect on work–family balance or an indirect effect mediated by the effect on time outside work satisfaction and time at work.

-

H3a

Time outside work satisfaction mediates the influence of flexible arrangement practices on work–family balance, so workers with flexible arrangement practices have more time outside work satisfaction, and this increase results in higher levels of work–family balance.

-

H3b

Time at work mediates the influence of flexible arrangement practices on work–family balance, so workers with flexible arrangement practices reduce their time at work, and this reduction results in higher levels of work–family balance.

Parental Leave Practices

Parental leave practices refer to how leave time allowance practices permit parents to take some time off to take care of their children or personal needs. Therefore, parental leave practices provide workers with an easier way of fulfilling their family duties, giving them more control in order to accomplish duties outside work and reducing the number of working hours. This is related to the principle of reciprocity noted in relation to flexible arrangement practices: the higher is the ability to request time off, the lower the number of hours employees will spend at their workplace to increase the number of hours they spend at home (Gray and Tudball 2002; Wolcott and Glezer 1995). Thus, it would be interesting to know whether the work–family balance derived from parental leave practices goes beyond the effect of time outside work satisfaction and on time at work.

-

H4a

Time outside work satisfaction mediates the influence of parental leave practices on work–family balance, so workers with parental leave practices have more time outside work satisfaction, and this increase results in higher levels of work–family balance.

-

H4b

Time at work mediates the influence of parental leave practices on work–family balance, so workers with parental leave practices reduce their time at work, and this reduction results in higher levels of work–family balance.

Method

Database

The dataset to test the model and the hypotheses described in the previous section come from the 2010 Quality of Working Life Survey (QWLS). This survey has been conducted by the Spanish Ministry of Labor and Immigration since 2001 in a representative sample of Spanish individuals who are 16 or older, for the purpose of obtaining information about employees’ quality of life at work, through information about activities occurring in their working and family environment and through different personal perceptions regarding conditions and relationships at work. Concretely, in 2010, the theoretical size of the sample is 9,240 Spanish individuals, whereas after the multi-stratified sampling design, the final sample is 8,061 individuals. More specifically, the questionnaire is structured in three sections. The first section collects sociodemographic data about the worker, such as education and gender. Section 2 contains information about the employee’s working life. The last section deals with employee’s quality of life at work, including, for example, information on work attitudes, work organization, and work–family balance.

Sampling Design

The sample is representative of those in employment during the fieldwork period covered. To guarantee sample representativeness, each target population is stratified according to region and size of municipality. A random walk procedure is then run in each census section to select the workers who are going to respond to the questionnaire. Since the survey is funded with public money, responses to it are compulsory. The data are collected by means of face-to-face interviews. Interviewers visit the homes of those in the sample between six and ten in the evening, in order to avoid localization problems among working people.

The sampling design is multi-stratified. Firstly, a stratification of primary sampling units is carried out in line with the census section. After this, the goal units are households in the register. In stage 3, the units are individuals aged at least 16. In each region, stratification according to municipality size is done. Finally, the selection of home and respondent is random.

Given the objective of this paper, observations from self-employed workers have been excluded. Moreover, because of missing data, our final sample comprises a total of 4,539 Spanish workers, in which 44.22 % are women, 56.80 % has children under 14 years old, and 66.73 % belong to a dual-earner couple. The average age for our sample is 42.37 years old. While only 13.44 of our sample have primary studies, 57.9 % have secondary studies and the rest university studies.

Measures

The goal of the paper is to analyze if family-friendly practices really contribute to work–family balance for women and men. Then, the dependent variable measures the degree to which people are satisfied with their work–family balance. In specific terms, individuals indicated their levels of satisfaction with their work and family balance using an 11-point Likert scale, where 0 is very unsatisfied and 10 very satisfied.

Two variables are considered in this study to mediate the effect that family-friendly practices have on work–family balance. These variables are time outside work satisfaction and working hours.

The independent variables in the paper are family-friendly practices. Following previous studies, family-friendly practices are classified into three broad subsets of practices (Ferrer and Gagné 2006; Glass and Finley 2002): family support practices, flexible work practices, and parental leave practices. The measures used are taken from Escot et al. (2012) that used a previous version of the sample database (see the Appendix). The first subset indicates if “your firm provides the workers with nurseries or help with nurseries and help for the education of children or family members.” The original answers for these questions were three categories (1 = yes, 2 = no, 3 = don’t know), whereas in our article, it has been re-coded to two (1 = yes, 0 = no). The second subset refers to flexible arrangement practices. In this case, those interviewed were questioned about the degree of satisfaction with their working day, with flexitime, and with holidays and leaves, using a scale of 0 to 10 where 0 is very unsatisfied and 10 very satisfied. The final subset refers to parental leave practices. Specifically, individuals indicated the “facilities” in their firm for requesting unpaid leave for family reasons, for requesting unpaid days off for family reasons, for taking time off for occasional private matters, and for requesting a shorter working day for family reasons. Each individual indicates how easy it is to request such benefits in their firm, using a 11-point Likert scale, where 0 indicates not easy at all and 10 indicates very easy.

Factor analysis techniques showed that while rooted in the same managerial philosophy, the nine initial practices considered do not load a unique latent factor. Rather, as previous literature has shown, they appear to be separate dimensions. Although these dimensions are positively correlated with each other, these relationships are not strong enough to consider them a reflection of the same underlying factor. The three indicators for each of the subsets of family-friendly practices are built by means of a factor analysis (Hair et al. 1998). The initial variables are reduced to three latent variables which matched the three factors whose eigenvalues were greater than 1 and which explained 74.5 % of the total variance. Moreover, the reliability of the scale for each one of the factors was validated, with Cronbach’s alpha scores of 0.739, 0.668, and 0.913, respectively.

Table 1 contains the main descriptive statistics for the dependent, mediating, and independent variables.

Finally, in accordance with the existing literature (Crooker et al. 2002; Frone et al. 1992; Guest 2002), we include several control variables: gender, age, educational level, civil status, number of children under 14, worker’s position, and firm size. Table 2 shows the mean and standard deviation for the control variables.

Results

Prior to running the procedure outlined in Baron and Kenny (1986) to test for mediation, we take a look at the descriptive statistics of the variables of our study to observe the general characteristics of the sample.

Sample Characteristics

The results of the MANOVA test indicated the significant main effect of gender on the dependent variables as well as on the independent and mediating variables. Hence, as there are differences by gender, the sample has been divided by gender, and the analyses were carried out separately for women and for men. Tables 1 and 2 present the main descriptors for all the variables used in the analysis.

Men have greater work–family balance than women as can be seen in Table 1. Women are less satisfied with time outside work, and they work fewer hours than men do. Regarding family support practices, women have more possibilities to receive help for nursery care as well as for education than men. Moreover, as for flexible arrangement practices, women are more satisfied than men with their working day and with holidays and leaves. Finally, in relation to parental leave practices, women have more facilities than men for requesting shorter working days.

Finally, with regard to control variables, Table 2 shows that there is a wide range of differences in almost all the control variables. On average, men are 2 years older than women. Regarding education, nowadays, it can be seen than women have higher education levels than men. The percentage of women with university education is greater than the corresponding percentage for men. Regarding the number of children under 14 that people have, men in our sample say to have more children under 14 at home than women. However, for civil status, the percentage of men belonging to a couple where the woman does not work is higher than the percentage of women.

Mediation Mechanism

According to the Baron and Kenny (1986) procedure to test for mediation, four conditions need to be satisfied, for which it is necessary to carry out three analyses. Firstly, the independent variables need to be significantly related to the dependent variables. Then, the dependent variable, work–family balance is regressed on the independent variables, family-friendly practices. In more specific terms, we start by estimating ordered probit models that regresses work–family balance on the control variables and the family-friendly practices. This equation allows us to test Hypotheses 1a, 1b and 1c. Secondly, the independent variables need to be significantly related to the mediator variables. So the mediators (time outside work satisfaction and time at work) are regressed on family-friendly practices. In this case, ordered probit model are used for time outside work satisfaction while linear regression models are estimated for time at work. Thirdly, the mediators need to be significantly related to the dependent variable, and fourthly the relationship between the independent variables and the dependent variable need to become lower or insignificant when the mediator is added to the model. To test these last conditions, the dependent variable (work–family balance) is regressed simultaneously on both the independent variables (family-friendly practices) and the mediator variables (time outside work satisfaction and time at work). This allow us to test H2a, H3a, H3b, H4a and H4b. Partial mediation occurs when, in the presence of mediator variables, the relationship between family-friendly practices and work–family balance is reduced in size and significance. Full mediation occurs when that previous relationship becomes insignificant and is essentially reduced to zero. To test this, ordered Probit models are estimated. Moreover, to test whether the mediation is statistically significant, we follow the common approach for single-step multiple mediator models. This is the approach proposed by Preacher and Hayes (2008). Results for the three models are presented in Table 3 for women and in Table 4 for men.

Relationships Between Family-Friendly Practices and Work–Family Balance

H1a stated that family support practices increase work–family balance more for men than for women, and H1b and H1c stated that flexible arrangement practices and parental leave practices increase work–family balance more for women than for men. These results are in the third column of Tables 3 and 4 for women and men, respectively.

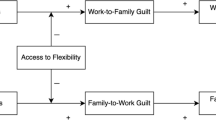

The results indicate that all subgroups of family-friendly practices are positively related to work–family balance, and these relationships are significant. Moreover, when we analyze the coefficients that measure this relation and compare them between women and men, it is possible to observe that the magnitude of the effect is different. In this sense, graphic representation of the results shows the effect of each subset of family-friendly practices on work–family balance for men and women. In specific terms, with respect to family support practices, Fig. 1 shows that the increase in work–family balance is greater for men than for women and, therefore, H1a is supported. However, Fig. 2 shows that the effect of flexible arrangement practices on work–family balance is similar for both women and men. Therefore, while flexible arrangement practices increase work–family balance for both genders, it is not possible to accept H1b. Finally, Fig. 3 shows that parental leave practices increases lead to greater work–family balance for women than for men. This provides support for H1c.

Relationships Between Family-Friendly Practices and Mediator Variables

To test if time outside work satisfaction and time at work mediated the relationship between family-friendly practices and work–family balance, the second condition is that the independent variables be significantly related to the mediators. The first and the second columns of Tables 3 and 4 show the results of these analyses. As can be observed, family support practices increase time outside work satisfaction for both genders, and these relationships are significant for both women and men. This is a necessary condition to test H2a. Also, flexible arrangement practices increase time outside work and decrease the number of work hours, for women and for men, which enables us to test H3a and H3b, respectively. Moreover, parental leave practices have the expected effect on time outside work satisfaction for women and for men, a necessary condition to test H4a. However, while parental leave practices decrease time at work for women, they do not affect time at work for men. Therefore, hypothesis 4b could only be tested for women.

Mediating Role of Time Outside Work Satisfaction and Time at Work

The third condition of mediation is that the mediator is significantly related to the dependent variable, which is shown in our models. For both women and men, time outside work satisfaction is positively related to work–family balance, while time at work is negatively related to it. The final condition is that the effect of family-friendly practices is lower or insignificant when the mediators are added to the model. This mediating role is shown in the last column in Tables 3 and 4.

According to H2a, time outside work satisfaction mediates the influence of family support practices on work–family balance. It is possible to observe that the effect of family support practices is no more significant for women, and the coefficient is lower in the case of men, but the relationship between family support practices and work–family balance for men still is significant. Moreover, following the procedure outlined by Preacher and Hayes, time outside work satisfaction explains 72.20 % of the total effect that family support practices have on work–family balance for men. For women, the results in Tables 3 show that time outside work satisfaction fully mediated the effect of family support practices on work–family balance. Thus, H2a according is confirmed for both genders.

Hypotheses 3a and b establish the mediating effect of time outside work satisfaction and time at work between flexible arrangement practices and work–family balance. It is possible to see that although the coefficient is significant for both genders, when all the variables are included in the analysis, they are lower than in the previous analysis. Moreover, the Preacher and Hayes approach shows that mediator variables explain 28.4 and 33.7 % of the total effect that flexible arrangement practices have on work–family balance for women and men, respectively. Thus, as time outside work satisfaction and time at work fulfilled the requirements of a partial mediator in the relationship between flexible arrangement practices and work–family balance, H3a and H3b are supported. Time outside work satisfaction and time at work mediate the effect of flexible arrangement practices on work–family balance for women and for men.

Finally, hypotheses 4a and b state that time outside work satisfaction and time at work mediated the effect of parental leave practices on work–family balance for women and for men. The results of the last estimation show that while the effect of parental leave practices is significant for both genders, the coefficient is lower than in the previous analyses where mediating variables are not included. This means that for women, both time outside work satisfaction and time at work mediated between parental leave practices and work–family balance. The Preacher and Hayes approach shows that partial mediation occurs in this case for women, as the mediator variables explain 45.7 % of the total effect that parental leave practices have on work–family balance. However, given that the effect on parental leave practices on time at work is not significant for men, the results show that only time outside work satisfaction mediated the effect of parental leave practices on work–family balance. In particular, the Preacher and Hayes approach shows that it explains 87.8 % of the total effect that parental leave practices has on work–family balance for men. Thus, H4a is supported for women and for men, while H4b is confirmed only in relation to women. H4b cannot be tested in relation to men.

On the whole, while the estimated effects of mediator variables were in the predicted direction, in general, they only partially mediated the relationship between each subset of family-friendly practices and work–family balance for both women and men.

Discussion

The aim of this paper was to contribute to the literature on the effects of family-friendly practices by testing a series of hypotheses about the effect of each one of the subset of family-friendly practices on work–family balance for both women and men. Besides the net main effects, the aim has also been to disentangle the mechanisms through which such effects occur, using as mediator variables time outside work satisfaction and time at work. In light of the caution required by the limitations related to single-item variables measuring the dependent construct and the usual causation caveats, the overall results show that the three subsets of family-friendly practices increase work–family balance for both women and men. Consistent with this idea of the existence of additional relevant factors, the analyses showed that the proposed model is, in general, a partial mediation model.

Our results indicate that some practices better accommodate women’s needs and others men’s needs, respectively. In particular, family support practices seek to help men and women to achieve work–family balance but maintaining the traditional vision of the ideal employee, that is someone working full time, committed to his or her work and with no outside responsibilities (Fursman and Callister 2009). These practices increase work–family balance more for men than for women. The other set of practices, parental leave, increases work–family balance especially for women. These practices, as noted in Bustelo and Peterson (2005), help women to combine their wish to be in a paid job with their social responsibility of being the main individual responsible for family tasks, helping women above all to combine work and family domains. Therefore, it seems that these practices better suit women who prefer to maintain the traditional maternal stereotype role (Martínez et al. 2011). Then, both subsets of family-friendly practices reinforce societal gender role expectations. This is in line with previous studies that find that Spain remains rooted in traditional stereotypes that emphasize different roles for women and men (Martínez et al. 2011).

However, flexible arrangement practices increase work–family balance for women and men, but there are no significant differences among genders. The fact that this subset of practices has the same effect on work–family balance for both gender shows that they cater equally to men and women preferences to manage multiple roles. This is in line with previous studies that show that there is a slight trend among Spanish men to express a greater desire to play a more active part in childcare and household work (Alberdi and Escario 2007; Holter 2007; Martínez et al. 2011) and for Spanish women to view wages and work–family balance as equally important (Dema and Díaz 2004; Moreno 2010; Rivero 2005; Torns and Moreno 2008).

As to whether the effect of family-friendly practices on work–family balance goes beyond the effect of time outside work and time at work, the partial mediation effect indicates that time is an important mechanism in achieving this objective. In line with the Voydanoff model, time outside work satisfaction mediates between family support practices and work–family balance for women and men. Moreover, the effect of family support practices on work–family balance for women is completely mediated by time outside work satisfaction, probably as a consequence of the decrease in the number of household tasks. Given that the participation of women in the workplace has not been mirrored by an equivalent increase in the participation of men in unpaid work (Goñi-Legaz et al. 2010), women value additional resources that help them to meet family demands for the effect that these resources have on their satisfaction outside work.

In line with the Clark border theory, practices that seek to rationalize time at work and time with family, and that allow people to integrate both domains of life, have a positive effect on work–family balance. Specifically, the effect of flexible work arrangement practices is mediated by time outside work satisfaction and time at work for both women and men. Moreover, likewise in line with the latter theory, the effect of parental leave practices on work–family balance goes beyond the effect on time outside work satisfaction and time at work for women, while its effect is limited only to time outside work satisfaction for men. In a country like Spain, one of the south Mediterranean countries characterized by a long working day and by a widespread split-shift work schedule that conflicts with family responsibilities (Amuedo-Dorantes and De la Rica 2009), family-friendly practices can help employees to achieve greater work–family balance.

The fact that in almost all cases partial mediation occurs may be accounted for by other aspects of the relationship between family and work is not taken into account in this research, such as psychological involvement in work and family roles (Frone et al. 1992; Greenhaus et al. 2003). Even more, the commitment to multiple roles can have a buffering effect against negative experience in one of them (Barnett and Hyde 2001) and that satisfaction in one domain may also lead to satisfaction in the other (Xu 2009).

Limitations and Future Research

Of course, this paper is not free of limitations. First of all, we did not have the opportunity to participate in the design of the questionnaire. The fact that the data are obtained from secondary data source and by means of face-to-face interviews, a measure of social desirability (Fisher and Katz 2000) cannot be included in the analysis. As work–family balance can be a sensitive subject, in face-to-face interviews, people can post a social desirability bias, doing that social desirability bias is a limitation in our study. Also, the use of secondary data limited the type of measures we could employ. As previously noted, such constraint was more noticeable in the case of single-item measures. Likewise, while our interest was in the effect of family-friendly practices on work–family balance, it would be interesting to analyze the real effects that the use of these practices may have. This may constitute an interesting avenue for future research, as it may enable a clearer understanding of the mechanisms that link the use of family-friendly practices and work–family balance.

Furthermore, the non-longitudinal nature of the datasets used in the article implies that the statistical relationships found in the article cannot be considered causal in the intended direction. Moreover, our data were collected in a specific country. While Spain is closely related in terms of work-related variables (Ronen and Shenkar 1985), gender egalitarianism (Javidan et al. 2006) and family patterns (Covre-Sussai et al. 2013) with other Latin European (Jesuino 2002) and Latin American countries (Idrovo et al. 2012), we should necessarily be cautious with regard to the generalizability of the results. Others factors, like economic and institutional–political factors, affect the use of human resource management practices (Fombrum et al. 1984), and, as a consequence, the determinants and consequences of work–family interface can be different across countries (Aycan 2008). Then, further research conducted in other geographical settings is warranted.

Finally, another limitation that needs to be highlighted is that in this paper firms’ culture, one of the factor that can limit the use of family-friendly practices, could not be measured. Sometimes employees cannot use practices as they are afraid of negative consequences, such as dismissal or wage reduction. Chinchilla et al. (2003) showed that so as to have an appropriate firm culture, encouraging the use of family-friendly practices was even more important to the effect on work–family balance than the actual practices. For the future, it would be interesting to measure firms’ culture in order to show if the effect of family-friendly practices on work–family balance varies depending on the prevailing culture of the workplace.

Conclusion and Practical Implications

In summary, offering employees family-friendly practices is a good starting point in order to increase people’s quality of life by helping them achieve work–family balance. However, our results show that different practices have different effects in women’s and men’s work–family balance. While the effect of the three subsets of family-friendly practices on work–family balance depends on gender needs, all of them increase work–family balance for women and for men. Family support practices have greater effect on work–family balance for men since they better accommodate men needs, while parental leave practices have greater impact on work–family balance for women since they better accommodate women needs. Moreover, in general, the effect of family-friendly practices on work–family balance partially goes beyond the effect of time outside work satisfaction and time at work. Human resource managers should take into account these results in order to design and offer a set of practices that fit well with employees’ needs and, as this, contributing to their well-being and quality of life. A good design of the family-friendly practices is a win–win strategy that should imply benefits for firms and benefits for employees.

References

Alberdi, I., & Escario, P. (2007). Los hombres jóvenes y la paternidad. Madrid: Fundación BBVA.

Allen, T. D. (2001). Family-supportive work environments: the role of organizational perceptions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 58, 414–435.

Allen, T. D., Herst, D. E. L., Bruck, C. S., & Sutton, M. (2000). Consequences associated with work-family conflict: a review and agenda for future research. Journal of Occupational Health Pyschology, 5, 278–308.

Álvarez, B., & Miles, D. (2003). Gender effect on housework allocation: evidence from Spanish two-earner couples. Journal of Population Economics, 16, 227–242.

Amuedo-Dorantes, C., & De la Rica, S. (2009). The timing of work and work-family conflicts in Spain: who has a split schedule and why? (IZA). Discussion Paper No. 4542.

Andrews, A., & Bailyn, L. (1993). Segmentation and synergy: two models linking work and family. In J. C. Hood (Ed.), Men, work and family (pp. 262–275). Sage: Newbury Park.

Arriagada, I. (2002). Changes and inequalities in Latin American families. CEPAL Review, 77, 135–153.

Ashforth, B. E., Kreiner, G. E., & Fugate, M. (2000). All in a day's work: boundaries and micro role transitions. Academy of Management Review, 25(3), 472–491.

Australian Telework Advisory Committee. (2006). Telework for Australian employees and businesses: maximising the economic and social benefits of flexible working practices. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

Aycan, Z. (2008). Cross-cultural approaches to work-family conflict. In K. Korabik, D. S. Lero, & D. L. Whitehead (Eds.), Handbook of work-family integration: research, theories, and best practices (pp. 353–370). San Diego, CA: Elsevier.

Balmforth, K., & Gardner, D. (2006). Conflict and facilitation between work and family: realizing the outcomes for organisations. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 35, 59–68.

Barnett, R. C., & Hyde, J. S. (2001). Women, men, work and family: an expansionist theory. American Psychologist, 56, 781–796.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Batt, R., & Valcour, P. M. (2003). Human resource practices as predictors of work-family outcomes and employee turnover. Industrial Relations, 42, 189–220.

Beauregard, T., Henry, A., & Lesley, C. (2009). Making the link between work-life balance practices and organizational performance. Human Resource Management Review, 19, 9–22.

Becker, P. E., & Moen, P. (1999). Scaling back: dual-career couples’ work-family strategies. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61, 995–1007.

Bosch, G., & Wagner, A. (2003). Service societies in Europe and reasons for service employment growth. Kølner Zeitschrift fur Soziologie and Sozialpsychologie, 55, 475–499.

Brough, P., O’Driscoll, M., & Kalliath, T. (2005). The ability of ‘family-friendly’ organizational resources to predict work-family conflict and job and family satisfaction. Stress and Health, 21, 223–234.

Brough, P., Holt, J., Bauld, R., Biggs, A., & Ryan, C. (2008). The ability of work-life balance policies to influence key social/organisational issues. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 46, 261–274.

Bustelo, M., & Peterson, E. (2005). Conciliación y (des)igualdad. Una mirada debajo de la alfombra de las políticas de igualdad entre mujeres y hombres. SOMOS Revista de Desarrollo y Educación Popular, 7, 32–37.

Carlson, D. S., & Frone, M. R. (2003). Relation of behavioral and psychological involvement to a new four-factor conceptualization of work-family interference. Journal of Business and Psychology, 17, 515–535.

Chinchilla, N., Poelmans, S., & León, C. (2003). Políticas de conciliación trabajo-familia en 150 empresas españolas. Documento de Investigación n° 498, IESE Business School, Barcelona.

Chinchilla, N., Masuda, A., & De Las Heras, M. (2010). Balancing work and family: no matter where you are. Amherst: HRD Press.

Clark, S. C. (2000). Work/family border theory: a new theory of work/family balance. Human Relations, 53, 747–770.

Covre-Sussai, M., Meuleman, B., Van Bavel, J., & Matthijs, K. (2013). Measuring gender equality in family decision making in Latin America: a key towards understanding changing family configurations. GENUS, 3, 47–73.

Crooker, K. J., Smith, F. L., & Tabak, F. (2002). Creating work-life balance: a model of pluralism across life domains. Human Resource Development Review, 1, 387–419.

Dancaster, L. (2006). Work-life balance and the legal right to request flexible working arrangements. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 9, 175–186.

De Simone, S., Lampis, J., Lasio, D., Serri, F., Cicotto, G., & Putzu, D. (2014). Influences of work-family interface on job and life satisfaction. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 9, 831–861.

Dema, S., & Díaz, C. (2004). La construcción de la igualdad en las parejas jóvenes: de los deseos a las prácticas cotidianas. Revista de Estudios de la Juventud, 67, 101–113.

Duxbury, L. E., & Higgins, C. A. (1991). Gender differences in work-family conflict. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, 60–74.

Edwards, J. R., & Rothbard, N. P. (2000). Mechanisms linking work and family: clarifying the relationship between work and family constructs. Academy of Management Review, 25, 178–199.

Encuesta de Población Activa. (2010). http://www.ine.es/jaxi/menu.do?type=pcaxisandpath=/t22/e308_mnuandfile=inebase

Escot, L., Fernández-Cornejo, J. A., Lafuente, C., & Poza, C. (2012). Willingness of Spanish men to take maternity leave. Do firms’ strategies for reconciliation impinge on this? Sex Roles, 67, 29–42.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1999). Social foundations of postindustrial economies. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ferrer, A., & Gagné, L. (2006). The use of family-friendly workplace practices in Canada. Institute for Research on Public Policy. Working Paper Series No. 2006–02.

Fisher, R. J., & Katz, J. E. (2000). Social-desirability bias and the validity of self-reported values. Psychology and Marketing, 17(2), 105–120.

Fletcher, J. K. (2005). Gender perspectives on work and personal life research. In M. Casper & R. B. King (Eds.), Workforce/workplace mismatch: work, family, health, and well-being (pp. 325–338). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Foley, S., Hang-yue, N., & Loi, R. (2005). Work role stressors and turnover intentions: a study of professional clergy in Hong Kong. Journal of Human Resource Management, 16, 2133–2146.

Fombrum, C. J., Tichy, N. M., & Devanna, M. A. (1984). Strategic human resource management. New York: N.Y. John Wiley & Sons.

Frone, M. R., Russell, M., & Cooper, M. L. (1992). Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict: testing a model of the work-family interface. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77, 65–78.

Frone, M. R., Yardley, J. K., & Markel, K. S. (1997). Developing and testing and integrative model of the work-family interface. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 50, 145–167.

Frye, N. K., & Breaugh, J. A. (2004). Family-friendly policies, supervisor support, work-family conflict, and satisfaction: a test of a conceptual model. Journal of Business and Psychology, 19, 197–220.

Fursman, L., & Callister, P. (2009). Men’s participation in unpaid care. A review of the literature. New Zealand: Department of Labour and the Ministry of Women’s Affairs.

Glass, J. L., & Finley, A. (2002). Coverage and effectiveness of family-responsive workplace policies. Human Resource Management Review, 12, 313–337.

Goñi-Legaz, S., Ollo-López, A., & Bayo-Moriones, A. (2010). The division of household labor in Spanish dual earner couples: testing three theories. Sex Roles, 63, 515–529.

Gray, M., & Tudball, J. (2002). Access to family-friendly work practices: differences within and between Australian workplaces. Family Matters, 61, 30–35.

Greenhaus, J. H., & Beutell, N. J. (1985). Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review, 10(1), 76–88.

Greenhaus, J. H., Collins, K. M., & Shaw, J. D. (2003). The relation between work-family balance and quality of life. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 63, 51–531.

Grzywacz, J. G., & Butler, A. B. (2005). The impact of job characteristics on work-to-family facilitation: testing a theory and distinguishing a construct. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 10, 97–109.

Grzywacz, J. G., & Carlson, D. S. (2007). Conceptualizing work–family balance: implications for practice and research. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 9, 455–471.

Guest, D. E. (2002). Perspectives on the study of work-life balance. Social Science Information, 41, 255–279.

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.). New York: Prentice Hall.

Hill, E. J. (2005). Work-family facilitation and conflict, working fathers and mothers, work-family stressors and support. Journal of Family Issues, 26, 793–819.

Hill, E. J., Hawkins, A. J., Ferris, M., & Weitzman, M. (2001). Finding an extra day a week: the positive influence of perceived job flexibility on work and family life balance. Family Relations, 50, 49–65.

Holter, Ø. G. (2007). Men’s work and family reconciliation in Europe. Men and Masculinities, 9, 425–456.

Hyman, J., & Summers, J. (2004). Lacking balance? Work-life employment practices in the modern economy. Personnel Review, 33(4), 418–429.

Idrovo, S., Carlier, C., LLorente, L., Grau-Grau, M., et al. (2012). Comparing work-life balance in Spanish and Latin-American countries. European Journal of Training and Development, 36(2/3), 286–307.

Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W., de Luqye, M. S., & House, R. J. (2006). In the eye of the beholder: cross cultural lessons in leadership from Project GLOBE. Academy of Management Perspectives, 20(1), 67–90.

Jesuino, J. C. (2002). Latin Europe cluster: from south to north. Journal of World Business, 37, 81–89.

Jokinen, K., & Kuronen, M. (2011). Research on families and family policies in Europe—major trends. In Uhlendorff, M. Rupp and M. Euteneuer (Eds.), Wellbeing of families in future Europe. Challenges for research and policy. Family platform—families in Europe, volume 1 (pp. 13–118). Family Platform.

Katz, D., & Kahn, R. L. (1978). The social psychology of organizations (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley.

Lambert, S. J. (1990). Processes linking work and family: a critical review and research agenda. Human Relations, 43, 239–257.

Łapniewska, Z. (2014). Well-being and social development in the context of gender equality. Working paper no. 1, Gender equality and quality of life—state of the art.

Martínez, P., Carrasco, M. J., Aza, G., Blanco, A., & Espinar, I. (2011). Family gender role and guilt in Spanish dual-earner families. Sex Roles, 65, 813–826.

McMillan, H. S., Morris, M. L., & Atchley, E. K. (2011). Constructs of the work/life interface: a synthesis of the literature and introduction of the concept of work/life harmony. Human Resource Development Review, 10, 6–25.

Md-Sidin, S., Sambasivan, M., & Ismail, I. (2008). Relationship between work-family conflict and quality of life. An investigation into the roles of social support. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 25(1), 58–81.

Milkie, M., & Peltola, P. (1999). Playing all the roles: gender and the work-family balancing act. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61, 476–490.

Moreno, A. (2010). Relaciones de género, maternidad, corresponsabilidad familiar y políticas de protección familiar en España en el contexto europeo. Madrid: Ministerio de Trabajo e Inmigración.

Northouse, P. G. (2007). Leadership: theory and practice (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc.

Nuño, L. (2008). La incorporación de las mujeres al espacio público y la ruptura parcial de la división sexual de trabajo: El tratamiento de la conciliación de la vida familiar y laboral y sus consequencias en la igualdad de género. Doctoral Thesis, University Complutense of Madrid, Madrid.

O’Driscoll, M., Brough, P., & Biggs, A. (2007). Work-family balance: concepts, implications and interventions. In S. McIntyre & J. Houdmont (Eds.), Occupational health psychology: European perspectives on research, education and practice (pp. 193–217). Portugal: ISMAI Publishers.

OECD. (2007). Babies and bosses. Reconciling work and family life. A synthesis of findings for OECD countries. Paris: OECD.

Parasuraman, S., & Greenhaus, J. H. (2002). Toward reducing some critical gap in work-family research. Human Resource Management Review, 12, 299–312.

Poelmans, S. (2008). Introduction. In S. Poelmans & P. Caligiuri (Eds.), Harmonizing work, family, and personal life: from policy to practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Poelmans, S., Chinchilla, N., & Cardona, P. (2003). The adoption of family-friendly HRM policies. Competing for scarce resources in the labour market. International Journal of Manpower, 24, 128–147.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Contemporary approaches to assessing mediation in communication research. In A. F. Hayes, M. D. Slater, & L. B. Snyder (Eds.), The Sage sourcebook of advanced data analysis methods for communication research. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Rau, B. L., & Hyland, M. M. (2002). Role conflict and flexible work arrangements: the effects on applicant attraction. Personnel Psychology, 55, 111–136.

Rice, R. W., Frone, M. R., & McFarlin, D. B. (1992). Work-nonwork conflict and the perceived quality of life. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 13(2), 155–168.

Rivero, A. (2005). Conciliación de la vida familiar y la vida laboral. Situación actual, necesidades y demandas. Madrid: Instituto de la Mujer.

Rode, J., Rehg, M. T., Near, J. P., & Underhill, J. R. (2007). The effect of work/family conflict on intention to quit: the mediating roles of job and life satisfaction. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 2, 65–82.

Rodríguez-Menéndez, M. C., & Fernández-García, C. M. (2010). Empleo y maternidad: El discurso femenino sobre las dificultades para conciliar familia y trabajo. Cuadernos de Relaciones Laborales, 28, 257–275.

Rodríguez-Nuño, V. (2006). La tasa de empleo femenino de España y sus Comunidades Autónomas en el marco de la Unión Europea y de la Estrategia de Lisboa 1990–2003, Boletín Económico de ICE, N° 2873, 43–50.

Ronen, S., & Shenkar, O. (1985). Clustering countries on attitudinal dimensions: a review and synthesis. Academy of Management Review, 12, 89–96.

Rothbard, N. P. (2001). Enriching or depleting? The dynamics of engagement in work and family roles. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46, 655–684.

Sánchez-Herrero, S., Sánchez-López, M. P., & Dresch, V. (2009). Hombres y trabajo doméstico: variables demográficas, salud y satisfacción. Anales de Psicología, 25, 299–307.

Sevilla-Sanz, A. (2010). Household division of labor and cross-country differences in household formation rates. Journal of Population Economics, 23, 225–249.

Silván-Ferrero, M. P., & Bustillos López, A. (2007). Benevolent sexism toward men and women: justification of the traditional system and conventional gender roles in Spain. Sex Roles, 57, 607–614.

Sirgy, M. J., Reilly, N. P., Wu, J., & Efraty, D. (2008). A work-life identity model of well-being: towards a research agenda linking quality-of-work-life (QWL) programs with quality of life (QOL). Applied Research in Quality of Life, 3, 181–202.

Torns, T., & Moreno, S. (2008). La conciliación de las jóvenes trabajadoras: Nuevos discursos, viejos problemas. Revista de Estudios de la Juventud, 83, 101–117.

Treas, J., & Widmer, E. D. (2000). Married women’s employment over the life course: attitude in cross-national perspective. Social Forces, 78, 1409–1436.

Valcour, M. (2007). Work-based resources as moderators of the relationship between hours and satisfaction with work–family balance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 6, 1512–1523.

Voicu, M., Voicu, B., & Strapcova, K. (2009). Housework and gender inequality in European countries. European Sociological Review, 25, 365–377.

Voydanoff, P. (2004). The effects of work demands and resources on work-family conflict and facilitation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 398–412.

Voydanoff, P. (2005). Consequences of boundary-spanning demands and resources for work-to-family conflict and perceived stress. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 10, 491–503.

Williams, M. L., Ford, L. R., Dohring, P. L., Lee, M. D., & MacDermid, S. M. (2000, August). Outcomes of reduced load work arrangements at managerial and professional levels: perspectives from multiple stakeholders. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management, Toronto, ON.

Wolcott, I. & Glezer, H. (1995). Work and family life: achieving integration. Australian Institute of Family Studies.

World Bank (2011). World development indicators. Washington, D.C.

Xu, L. (2009). View on work-family linkage and work-family conflict model. International Journal of Business and Management, 4, 229–233.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Education ECO2013-46954-C3-1-R awarded to Salomé Goñi-Legaz and ECO2013-48496-C04-2-R awarded to Andrea Ollo-López.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Goñi-Legaz, S., Ollo-López, A. The Impact of Family-Friendly Practices on Work–Family Balance in Spain. Applied Research Quality Life 11, 983–1007 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-015-9417-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-015-9417-8