Abstract

Mental illnesses and substance use disorders are prevalent worldwide and considered among the most stigmatizing of all health conditions. Stigma continues to create major barriers to treatment, recovery, quality of life, and social and economic injustice. The literature on mental illness and substance use stigmatization is becoming increasingly robust, reinforcing several important priorities for stigma reduction—such as stigma-informed education, meaningful involvement of people with lived experience of a mental illness or substance use disorder, recovery-oriented care, addressing barriers to access within our systems of care, and addressing stigma at the level of structures, laws, and policies. The 16 papers in this Special Issue build out this existing knowledge by highlighting a broad range of issues, perspectives, theoretical contributions, and stigma reduction approaches across different countries and contexts, and through various lenses. We have been particularly interested in selecting manuscripts that enhance our understanding of how stigma toward mental illness and substance use manifests itself and the factors involved in stigmatization processes. This knowledge can guide priorities and direction that can be used as a basis for designing and implementing strategies for change, and have the potential to lead to lasting and meaningful improvements for people with lived experience of mental illness or substance use disorder.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

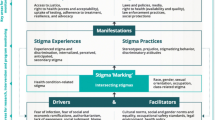

Stigma continues to create major barriers to treatment, recovery, quality of life, and social and economic injustice. Mental illnesses and substance use disorders are prevalent worldwide and considered among the most stigmatizing of all health conditions. Stigmatization is embedded in discriminatory and inequitable health and social policies and laws, exists in interpersonal relations, interactions, and public attitudes, and is also internalized within the self as ‘self-stigma’. Stigmatization is also intersectional, with negative effects compounded with the convergence of multiple stigmatized identities. These complexities make the ongoing challenges of understanding stigmatization processes and developing stigma reduction strategies equally complicated. Thus, it is critical to disseminate interdisciplinary research that furthers our understanding of the sources, expressions, and impacts of mental illnesses and substance use-related stigma and that identifies multilevel interventions to reduce stigma—including frameworks, promising and best practices, measurement tools, and theories of change.

Indeed, the literature on mental illness and substance use stigmatization is becoming increasingly robust, reinforcing several important priorities for stigma reduction—such as stigma-informed education, meaningful involvement of people with lived experience of a mental illness or substance use disorder, recovery-oriented care, addressing barriers to access within our systems of care, and addressing stigma at the level of structures, laws, and policies. The papers in this Special Issue build out this existing knowledge, adding further evidence and direction to research and intervention priorities on stigma and stigma reduction. The 16 research papers that make up this Special Issue provide a rich breadth of international stigma research related to mental illnesses, substance use, and intersectional stigma, and investigate stigmatization processes at multiple levels of its manifestation.

For example, Vega et al. (2022) from the University of Concepción in Chile undertook a systematic review of explanatory models of internalized mental illness stigma, illuminating key mechanisms in its development and providing direction for intervention strategies. Their findings reinforce the importance of prioritizing interventions that help people reframe their negative beliefs about mental disorders, that use peer involvement/people with lived experience to support positive group identification, that involve supportive disclosure strategies, and that encourage collective action. Caqueo-Urízar et al. (2022), also interested in the phenomenon of internalized stigma, examined the relationship between internalized mental illness stigma and recovery in a cross-sectional study of 165 patients with schizophrenia in Chile. Their findings provide additional support for previous research in this area and demonstrate, above all, the important role of hope for personal recovery and stigma resistance.

Building on the modified labelling theory of mental illness stigma (Link et al., 1989), Fernandez et al. (2022) examined the role of categorical versus continuum beliefs about depression and schizophrenia on stigmatizing attitudes and help-seeking intentions in a sample of Australian adolescents. While their results were consistent with other literature in showing that continuum beliefs are correlated with more favourable attitudes, their study also revealed that stronger continuum beliefs towards schizophrenia were actually associated with lower help-seeking intentions, a novel finding that may have implications for the design of anti-stigma interventions for this age group, particularly in relation to schizophrenia.

Substance use-related stigma is also an important focus of this Special Issue, with several papers directed to this topic specifically. Ghosh et al. (2022) content analysis of Indian online news articles highlights the role of the media in reinforcing stereotypes and stigmatizing perceptions toward people with substance use problems, finding that they tend to deliver little information on scientific and medical aspects of substance use. The authors point out the need for media guidelines on the reporting of substance use and provide some recommendations in this regard.

Also, in response to the challenges faced by many countries with high rates of opioid-related overdose deaths and opioid-use disorders—and hence, opioid-related stigma—Knaak et al. (2022) provide research from a Canadian context that reports on results of psychometric testing of a new scale to assess opioid-related stigma in health providers and other direct service provider populations, known as the Opening Minds Provider Attitudes Towards Opioid-use Scale (OM-PATOS). Reynolds et al. (2022), also reporting from a Canadian context, provide results of a study on people’s perceptions of harm reduction in relation to opioid-related stigma among a sample of university students. In addition to learning that many students hold misconceptions and have a lack of knowledge about harm reduction, their results show, perhaps encouragingly, that students hold more favourable attitudes towards people who engage in opioid agonist therapy (OAT) as compared to those who engage in no harm reduction behaviours. In contrast, Chou et al. (2022) qualitative study on American women’s experiences in receiving medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder revealed the continued existence of stigma towards this treatment modality (e.g.,’it’s still a drug’) to be common among family members, which was also often internalized by women themselves—and that such stigma further complicates treatment efforts and family relationships. This research also highlighted how support from peers is an important protective factor for resisting opioid-related stigma.

The complexities of intersectional stigma are explored in two papers on sexual and gender identity stigma, both of which show how the experience of sexual or gender identity stigma—whether anticipated, perceived, or enacted—also negatively impacts mental health and access to health care. In one study, Moallef et al. (2022) undertook a national survey to investigate the extent to which sexual and gender identity stigma, both anticipated and enacted stigma, impacts people’s ability to access primary and mental health care in Thailand. In another study by Okonkwo et al. (2022), the role of sexual behaviour stigma is investigated as a determinant of depressive symptoms among men who have sex with men and transgender women in Kigali, Rwanda.

While not a direct investigation of stigma specifically, Caro-Cañizares et al. (2022) studied barriers to obstetric care among pregnant women at risk for dual pathology of mental health and substance use problems in the metropolitan area of Madrid, Spain. While their study found some good news—namely that the vast majority of women attended all scheduled prenatal appointments—they also identified that attendance rates negatively correlated with stigmatized conditions of depression, post-traumatic stress symptoms, and alcohol use disorder.

Over the past few years, online stigma reduction interventions have begun to be used, and this Special Issue expands knowledge of some of these interventions. For example, Cangas et al. (2022) from the University of Almeria in Spain build on previous work (Cangas et al., 2017) on Stigma Stop—a serious game intervention where players interact with different characters with mental disorders to gain their collaboration and carry out a group task. In their current research, they designed an experiment to deliver the intervention in conjunction with traditional face-to-face interaction with people with lived experience of a mental disorder, using only a social contact intervention, and a control scenario. Their evaluation results showed that the serious game enhanced the anti-stigma effects of the social contact intervention, particularly with respect to reducing perceived dangerousness of people with mental disorders.

The Special Issue also provides a series of three manuscripts that describe a program of research on The Computer-Based Drug and Alcohol Training and Assessment in Kenya (eDATA-K), a substance use anti-stigma intervention for health providers. The first two articles (Clair et al., 2022b, c) present the results of blended-eLearning courses on health worker substance use stigma and on health worker delivery of alcohol use screening and brief interventions, including how they positively changed their attitudes toward those with substance use disorders. The third paper (Clair et al., 2022a) presents the result of a subsequent blended-eLearning intervention on quality improvement and how it helped sustain the services for at least six months after the research infrastructure and incentives of the RCT were removed.

Lastly, Smith et al. (2022) commentary article addresses the issue of stigma within the healthcare system, pointing out how existing research often restricts examinations of stigma to the interpersonal and individual level only, with much less understanding of how to address the problem of stigma at the organizational, structural, and cultural levels. Their commentary describes key components of a five-year study that will address stigma holistically (i.e. at multiple levels). The central goal of this research will be to implement and evaluate interventions that mitigate stigma at both the individual and cultural/organizational levels within emergency care at one Canadian hospital. Also central to this study is their commitment to stigma-informed research through the inclusion of a patient research partner as an integrated member of the research team.

The intention of this Special Issue has been to highlight a broad range of issues, perspectives, theoretical contributions, and stigma reduction approaches related to mental illness and substance use stigma across different countries and contexts, and through various lenses. We have been particularly interested in selecting manuscripts that enhance our understanding of how stigma toward mental illness and substance use manifests itself and the factors involved in stigmatization processes. This information can guide priorities and directions for reducing it-research and knowledge that, if acted upon and used as a basis for designing and implementing strategies for change, have the potential to lead to lasting and meaningful improvements for people with lived experience of mental illness or substance use disorder.

References

American Psychological Association. (2020). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.). American Psychological Association.

Cangas, A. J., Navarro, N., Aguilar-Parra, J. M., Ojeda, J. J., Cangas, D., Piedra, J. A., & Gallego, J. (2017). Stigma-Stop: A serious game against the stigma in mental health in educational settings. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1385. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01385

Cangas, A.J., Sanchez-Lozano, I., Aguilar-Parra, J.M., & Trigueros, R. (2022). Combination of a serious game application and direct contact with mental health patients, IJMHA (This Issue).

Caqueo-Urízar, A., Ponce, F., Urzúa, A. (2022). Effects of recovery measures on internalized stigma in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia, IJMHA (This issue).

Caro-Cañizares, I., Camacho, R.C., Mariño, C.V., Carpintero, N.L., Enrique Baca-García, E. (2022). Barriers to obstetric prenatal care among pregnant women at risk for dual pathology. IJMHA (This Issue).

Chou, J.L., Patton, R., Cooper-Sadlo, S., Swan, C., Bennett, D., McDowell, D., Zaarur, A., Schindler, B. (2022). Stigma and medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) among women, IJMHA (This Issue).

Clair, V., Atkinson, K., Musau, A., Mutiso, V., Bosire, E., Gitonga, I., Small, W., Ndetei, D., Frank, E., (2022a). Implementing and sustaining brief intervention with the support of a quality improvement blended-eLearning course: Positive learner experience and meaningful outcome in Kenya as part of eDATA-K, IJMHA (This Issue).

Clair, V., Musau, A., Mutiso, V., Tele, A., Atkinson, K., Rossa-Roccor, V., Ndetei, D., Frank, E. (2022b). Blended-eLearning Improves Alcohol Use Care in Kenya: Pragmatic randomized control trials results and parallel qualitative study implications, IJMHA (This Issue).

Clair, V., Rossa-Roccor, V., Mutiso, V., Musau, A., Rieders, A., Frank., E., Ndetei, D. (2022c). Blended-eLearning impact on health worker stigma toward alcohol, tobacco and other psychoactive substance users, IJMHA (This Issue).

Fernandez, D. K., Frank P. Deane, F. P., & Vella, S. A. (2022). Adolescents’ continuum and categorical beliefs, help-seeking intentions, and stigma towards people experiencing depression or schizophrenia, IJMHA (This Issue).

Ghosh, A., Naskar, C., Sharma, N., Fazl-e-Roub, Choudhury, S., Basu, A., Pillai, R. R., Basu, D., Mattoo, S. K. (2022). Does online news media portrayal of substance use and persons with substance misuse endorse stigma? A qualitative study from India, IJMHA (This Issue).

Knaak, S., Patten, S., Stuart, H. (2022). Measuring stigma towards people with opioid use problems: Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis of the Opening Minds Provider Attitudes Towards Opioid- use Scale (OM-PATOS), IJMHA (This Issue).

Link, B. G., Cullen, F. T., Struening, E., Shrout, P. E., & Dohrenwend, B. P. (1989). A modified labeling theory approach to mental disorders: An empirical assessment. American sociological review, 400–423.

Moallef, S., Salway, T., Phanuphak, N., Kivioja, K., Pongruengphant, S., Hayashi, K. (2022). The relationship between sexual and gender stigma and difficulty accessing primary and mental healthcare services among LGBTQI+ populations in Thailand: Findings from a national survey. IJMHA (This Issue).

Okonkwo, N., Twahirwa Rwema, J. O., Lyons, C., Liestman B., Nyombayire, J., Olawore, O., Nsanzimana, S., Mugwaneza, P., Kagaba, A., Sullivan, P., Allen, S., Karita, E., Baral, S. (2022). The relationship between sexual-behaviour stigma and depression among men who have sex with men and transgender women in Kigali, Rwanda: A cross-sectional study, IJMHA (This Issue).

Reynolds, G., Lindsay, B., Knaak. S., Szeto, A. C. H. (2022). Opioid use stigma: An examination of student attitudes on harm reduction strategies, IJMHA (This Issue).

Smith, J., Knaak, S., Szeto, A. C. H., Chan, E., Smith, J. (2022)., Individuals to systems: Methodological and conceptual considerations for addressing mental illness stigma holistically, IJMHA (This Issue).

Vega, D. F., Grandón, P., López-Angulo, Y., Vielma- Aguilera, A. V., Castro, W. P., (2022). Review of explanatory models of internalized stigma in people diagnosed with a mental disorder. IJMHA (This Issue).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

All three authors are also co-authors on one or more of the papers published in the Special Issue.

Ethical Approval

None.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

Research for this article did not involve human subjects research.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Knaak, S., Grandón, P. & Szeto, A.C.H. Interdisciplinary and International Perspectives on Mental Illness and Substance Use Stigma. Int J Ment Health Addiction 20, 3223–3227 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-022-00935-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-022-00935-6