Abstract

Integrated dual disorder treatment is an evidence-based practice for coordinating complex care for people with severe mental illnesses and comorbid substance use disorders in a single program. Despite its effectiveness, the program can be difficult to implement and is not routinely implemented in Veterans Health Administration settings. This study sought to better understand factors in implementation of this model using. We evaluated the model in four different programs at two Veterans Health Administration medical centers and documented costs associated with implementation efforts at one site. We used interviews and observations to characterize factors (with initial coding based on the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research) impacting implementation. Critical factors included the perceived usefulness of the model for patients served by the program, the need for ongoing case-based coaching after initial training, staff openness to stage-wise approaches as opposed to abstinence-only interventions, leadership at both the team and upper-level manager levels, and the need for model adaptation within varied program settings. Costs for implementation were relatively modest for both programs observed. These results should inform future efforts to implement the model in Veterans Administration and are also relevant to implementation challenges in other mental health service settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Comorbid mental health and substance use disorders (SUDs) are common and complicate clinical presentation and prognosis, requiring careful coordination of treatment for both conditions. Among adults with severe mental illnesses (SMI), SUDs are among the most common and clinically significant comorbid disorders (Kessler et al., 2005; Mueser et al., 1992, 2000). People with SMI also are at substantially greater risk of developing SUDs compared to the general public. For example, one recent study documented that rates of comorbid recreational drug use for people with psychotic illness was far greater than rates found for general population controls (OR = 4.62) (Hartz et al., 2014). For veterans, the problem of comorbid mental health and SUDs is also a significant concern. Nearly 1 out of every 5 veterans receiving Veterans Health Administration (VA) mental health care are dually diagnosed with both mental health and SUD (Institute of Medicine, 2006). When examining comorbid substance use disorder rates among veterans receiving care for psychiatric conditions, rates range from 21 to 60%, with higher rates of comorbidity among veterans with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia (Petrakis et al., 2011). In meta-analyses across a wide range of studies, largely civilian populations, the rate of SUD among people with schizophrenia was 42% (Hunt et al., 2018) and among people was 50% or higher (Hunt et al., 2016).

Comorbid SMI and SUDs have been associated with a wide range of negative outcomes, including higher rates of psychiatric relapse and re-hospitalization (Drake et al., 1989), homelessness (Caton et al., 1994; Edens et al., 2011; Osher et al., 1994), serious infectious disease (Rosenberg et al., 2001), violence (Bowers et al., 1990), incarceration (Abram & Teplin, 1991), disability, and unemployment (Zivin et al., 2011). Additionally, there is some evidence that substance use may interfere with the effectiveness of commonly prescribed psychopharmacological treatments (Bowers et al., 1990). Not surprisingly, these negative outcomes generally translate into greater service utilization resulting in higher costs for families (Clark, 1994) and communities (Bartels et al., 1993). Given the high rates of comorbid mental health and substance use disorders among veterans receiving VA healthcare, the implications for negative consequences in VA settings is substantial.

Studies have consistently shown that the traditional approach of parallel but separate mental health and substance abuse treatment is ineffective for consumers with dual disorders (Dixon et al., 2010; Drake et al., 2004; Drake et al., 2008; Ridgely et al., 1987). To be most effective, services for both mental health and substance use disorders should be carefully coordinated to support recovery from both conditions. Integrated dual disorder treatment (IDDT) is an evidence-based practice for people with SMI and co-occurring SUD that integrates mental health and substance abuse interventions on the same team, working in one setting, providing individualized treatment and rehabilitation for both disorders in a coordinated fashion (Drake et al., 2001a). Contrary to traditional treatment for dual disorders, IDDT does not require abstinence as a prerequisite to pursuing housing or employment. This is an important distinction, as research has shown that meaningful activities, social supports, safe housing, and a supportive therapeutic relationship are strongly correlated with consumers’ efforts to reduce substance use (Alverson et al., 2000). Integrated treatment is superior to nonintegrated approaches in reducing substance use and in producing positive outcomes in some other domains (Dixon et al., 2010; Drake et al., 1998; Drake et al., 2008; Kikkert et al., 2018), even after long-term follow-up (Drake et al., 2016, 2020).

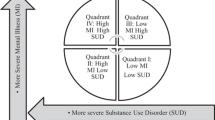

Although IDDT is a complex intervention where some of the empirical evidence comes from diffuse studies of clusters of interventions (Drake & Bond, 2010), the literature has identified critical components of IDDT programs that show good consumer outcomes; when these components are not present, outcomes are generally poor (Drake et al., 2001a; Havassy et al., 2000). These components include the following: (1) stage-wise treatment interventions based on stage of change including engagement, persuasion, active treatment, and relapse prevention (Drake et al., 2008); (2) assertive outreach to consumers and significant others to reduce dropout and noncompliance rates (Hellerstein et al., 1995; Ho et al., 1999; Mercer-McFadden et al., 1997); (3) motivational interventions to increase readiness for change and more active interventions (Dixon et al., 2010); (4) substance abuse counseling provided in individual, group, or family formats to help consumers to manage their illness and gain the skills and support needed for symptom control and ongoing abstinence (Dixon et al., 2010; Drake et al., 2008; Mueser et al., 1998); (5) social supports that embrace sober living (Alverson et al., 2000); (6) long-term intervention and support (Drake et al., 1998, 2001a; McHugo et al., 1999), (7) access to comprehensive, integrated services including crisis intervention, inpatient hospitalization, medication management, money management, housing, and vocational rehabilitation (Alverson et al., 2000; Drake et al., 2008; Greenfield et al., 1995) that are provided within a cohesive team of providers; and (8) culturally competent practice (Drake et al., 2001a). Contingency management has also emerged as an important component of integrated treatment in a recent review (Drake et al., 2008). Although not considered a critical element in early conceptualizations of IDDT, the use of peer providers in a large statewide roll-out of IDDT outside VA was associated with higher fidelity to the model Harrison et al., 2017a).

Drake and colleagues (2001b) identified IDDT as one of the six evidence-based mental health practices targeted for dissemination as part of the National Implementing Evidence-Based Practices Project (Drake et al., 2001b), a large national study in routine community mental health settings. Consequently, IDDT implementation has been attempted in a range of settings (e.g., rural and urban settings, diverse racial and ethnic groups) with varying degrees of success in achieving full fidelity (Boyle & Kroon, 2006; Brunette et al., 2008; Chandler, 2009; Harrison et al., 2017a, 2017b; Mercer-McFadden et al., 1997). Unfortunately, IDDT is not universally implemented in routine practice, including in VA facilities, and in some cases may require significant reorganization when programs are defined along traditional parallel treatment lines. Better understanding of implementation contexts and practice adaptions are increasingly important in understanding how best to implement evidence-based practices (Hoej et al., 2019).

The purpose of this study was to pilot test the IDDT model in VA settings and inform future implementation efforts for IDDT in the VA by addressing two specific objectives: (1) identify barriers and facilitators to VA implementation following the broad domains of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) (Damschroder et al., 2009), via a qualitative evaluation in four pilot sites, varying on both implementation duration and program type, and (2) document costs associated with providing and receiving IDDT implementation supports to inform future implementation efforts.

Methods

Settings and Programs

We purposefully selected four programs located at two VA medical centers which represented different program settings and experience in using IDDT. As seen in Table 1, two programs were Mental Health Intensive Case Management (MHICM) teams, one was a Psychiatric Rehabilitation and Recovery Center (PRRC), and one was a Housing and Urban Development VA Supported Housing (HUD VASH) team. All staff, regardless of program, were medical center employees. MHICM services are loosely based on the assertive community treatment model (Stein & Test, 1980), serving veterans at risk for psychiatric hospitalization, incarceration, and/or homelessness who may be less well served by traditional office-based mental health services. MHICM services are intensive, frequent, and community-based and include assertive outreach to engage and retain veterans in care. PRRC programs provide outpatient recovery services for veterans with a wide range of mental health disorders, including those with comorbid substance use disorders. The structure of PRRC teams and format for their services can vary across the USA, but mandated services involve psychiatric medication management, group, and individual psychiatric rehabilitation services that focus on improving both symptoms and overall functioning to support a healthy life in the community. HUD VASH programs also vary by structure and function but are designed to provide supported housing to veterans who receive special veteran-designated HUD vouchers. Nationwide, HUD VASH programs are intended to follow the Housing First model (Tsemberis & Eisenberg, 2000), a model where housing is provided with minimal requirements to participate in treatment services but with ample use of creative engagement strategies to facilitate treatment and promote housing stability. All four programs strive to assist veterans with SMI to achieve their personalized recovery goals in the community.

At the first VAMC, the MHICM team (Program A) was co-located with a PRRC (Program B). The MHICM Program A was a large team with 15 staff, including a team leader, peer specialists, social workers, registered nurses (RNs), and a psychiatrist. The team was located away from the main hospital setting. The PRRC program (Program B) was located in the same hospital system with the large MHICM team (Program A) and both shared an overarching leadership structure within their facility. The PRRC program included 7 staff: a psychologist program leader, three peer support specialists, a certified nurse specialist, an RN, and social worker. These two programs had been receiving externally provided technical assistance and training on IDDT for 2 years prior to the study, initiated outside of research procedures. Because of their previous active implementation experience in IDDT, we refer to these two programs as more “mature” in their implementation of IDDT, as opposed to the two “new” early-phase implementation programs.

At the second VAMC, a MHICM team (Program C) was co-located with a Housing and Urban Development VA Supported Housing (HUD VASH) team (Program D). This VAMC’s programs (Programs C and D) started implementation with this study (“newly implementing”) and used a different external facilitator, funded by the research project. MHICM Program C was much smaller than the first MHICM Program A, with only four full-time staff including a team leader, two social workers, a certified nurse specialist, and a small percentage of effort from a psychiatrist based at the main hospital location (approximately a mile away from the MHICM team). This team also had a volunteer peer specialist who worked occasionally with veterans. The HUDVASH Program D was co-located in the same office space with the newly implementing MHICM team, although their leadership “chain of command” was Social Work service, whereas the MHICM team reported to psychiatry service. The HUDVASH team was budgeted for 20 FTE, although staffing was 18 FTE for the majority of the study period. Staffing included a team leader, one peer specialist, two substance abuse specialists, and multiple registered nurses and social workers.

Implementation Process

For each program, implementation began with external facilitation that included intensive onsite clinical training for staff, a baseline and 12-month fidelity assessment with report and recommendations, and ongoing monthly consultation for the first year of implementation. For the two mature programs (A and B), facilitation was ongoing but included brief visits or phone calls every 2–3 months.

Procedures: Barriers and Facilitators of Implementation

Five study investigators with PhDs in a clinical field and who were familiar with IDDT and VA mental health services conducted interviews in all four programs and observed implementation events in the two new Programs (C and D). Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and de-identified. At baseline of this study (prior to implementation at programs C and D), interviews were conducted with key stakeholders at all four programs (n = 39), including three administrators with authority over the implementing programs, four program leaders, 31 implementing staff, and one veteran recipient of IDDT services. For implementing staff, we interviewed a broad range of team participants, representing diverse team roles across the four programs, including social workers, psychologists, nurses, peer specialists, vocational rehabilitation specialists, and addiction counselors. For the two newly implementing programs, we also conducted 12-month follow-up interviews with a subset of participants: two program leaders, an administrator, and six staff. A total of 48 interviews took place either in person or over the phone and typically were 30–45 min in length. Written informed consent was obtained from all interviewed subjects. While observing implementation events, study investigators also wrote observation memos during and after the event. All human subject research procedures were approved by the university Institutional Review Board and the VA Research and Development committee responsible for monitoring the study team’s research ethics.

Interviews

The semi-structured interview questions followed the CFIR domains thought to impact implementation: intervention characteristics, characteristics of individuals involved, inner setting, outer setting, and the implementation process (Damschroder et al., 2009). Intervention characteristics include the nature of the practice being implemented, such as the advantages of the approach (e.g., evidence that the model works), skills necessary to implement it, the program’s adaptability for various settings, or its complexity or cost. IDDT’s inclusion of advanced clinical techniques and underlying harm reduction philosophy have had significant impact on implementation (Drake & Bond, 2010). Relatedly, the people providing the intervention bring with them certain characteristics, skills, attitudes, and experiences that affect implementation. Implementation takes place within an inner setting or the program actually providing the service. The inner setting might include team structure, culture, climate, or readiness to engage in the new program. The inner setting is variably affected by the outer setting which includes the broader treatment system, the needs of veterans served by the larger context, and local socio-political environment (e.g., incentives that influence a program’s decision-making regarding interventions and programs). Finally, implementing agencies vary in the strategies and implementation tools (implementation process) that they employ in putting a new practice into place, such as planning and engagement in implementing the program, facilitation and training in the program, or using internal champions or opinion leaders in the implementation process.

Interviews typically began with a broad question followed by more specific follow-up probes consistent with CFIR domains. As an example, the early part of the interview began with “We would like to start by getting your perspective on why and how your program decided to implement IDDT. Tell us as much as you can about who made the decision to implement.” Follow-up questions to this broad opener included “Are you aware of any dissent or disagreement among staff with the decision to implement IDDT? Why/why not?” and “Were there VA policies that influenced this decision?” and “What other external factors influenced this decision?” and “What influenced the decision to implement IDDT in this particular program/setting over others?”. Similarly constructed opening questions and probes were used for other key aspects in each CFIR domain.

Analyses

The same study team members who collected data served as qualitative coders. The study team used a rapid, deductive approach, assigning coding categories to roughly correspond to broad CFIR domains (Damschroder et al., 2009). For the purposes of this work, we included facility and VACO-level themes as outer context themes because, in many cases, these programs viewed themselves as cohesive units separated from their facility and sometimes separated even from other programs within the same facility’s service line. Inner context was restricted to team level culture, structure, and other characteristics dictated by the program itself. For team characteristics dictated by external facility or other policies, we coded those characteristics as outer context because they were influenced by policies external to the team.

Consistent with rapid qualitative analysis techniques (Hamilton, 2013), the study team held intensive coding sessions early in the project to code sample interviews and observations. Coders critiqued one another’s work, discussed clarifications regarding the coding framework, and added detail to the codebook for reliability. Investigators then coded all interviews and observation events using the refined codebook. Later, study investigators compiled a program-level summary template (site profile) synthesizing barrier and facilitator themes corresponding to each implementation domain. Midway through the project, study investigators convened an expert panel of both local and VA Central Office leaders to reflect on site profiles and preliminary findings.

Implementation Support Cost Identification Data Collection and Analyses

For cost identification to capture the costs of supporting implementation of the clinical practice, we prospectively collected reports on each facilitation event for the two newly implementing sites (C and D), using sign-in sheets, observations, and facilitator logs of phone calls and email contacts outside of scheduled events. For each staff person taking part in an implementation activity, we aggregated time spent (e.g., in fidelity assessment, training, coaching, planning, and shadowing efforts) and multiplied the time by the individuals’ published salary, plus 30% fringe. We used annualized data for ease of interpretation.

Results

Barriers and Facilitators by Implementation Factor

In addressing the study’s first objective, analyses resulted in a synthesis of barrier and facilitator themes by IDDT program type and age, organized by primary implementation factor category: intervention characteristics, people, inner context, outer context, and implementation process.

Intervention Characteristics

IDDT was described as advantageous by multiple respondents from the mature teams and by early champions within the newer teams. Aspects of IDDT that they found useful included the use of MI, staging, and harm reduction to engage veterans in active treatment. One peer specialist noted:

“I like the approach. It’s not really that directive…you’re actually getting the answers to come from them. So, I thought it was beautiful...it gives you [as the veteran] the authority or…the power to change on your own…it puts the ball back in their court.”

However, there was some dissent amongst staff who felt the model required too much “chasing” of veterans unwilling to address their substance use: “It’s time consuming to run after people. So I don’t agree with that part.” The mature team leaders liked the fact that the model is packaged with its own fidelity scale, even if some expressed concerns with some of the scale’s scoring rules. They also endorsed the value of facilitators providing visual aids to help staff learn the clinical staging required by IDDT. The adaptability and flexibility of the model also was endorsed as a positive by some. For example, interviewees highlighted how the model does not require clinical knowledge regarding “which came first”—MH or SUD—and this “makes things easier.” Conversely, a common refrain on all teams was a desire for more concrete clarifications about what the IDDT model indicates as an appropriate intervention for a particular veteran, based on stage of change.

Staff were inconsistent in their depiction of IDDT’s complexity, with some referring to the model as “simple” and others finding that the staging of veterans complicated treatment planning. Several respondents referred to IDDT’s components as consistent with other important aspects of their teams, including the assertive community treatment model for the MHICM teams, Housing First for the HUD VASH team, and recovery-oriented care principles such as honoring client choice and self-determination. Several respondents commented on the “fit” of IDDT with their current services. The mature MHICM IDDT program gave examples including community-based outreach provided by the MHICM team as consistent with IDDT.

Characteristics of Individuals

All four program leaders highlighted the helpfulness of an individual staff person’s willingness to learn the model or, conversely, the barrier of staff resistance. One common barrier was staff preference for confrontation over IDDT’s less traditional emphasis on engagement and enhancing motivation for veterans who continue to use substances. In general, experience with motivational interviewing, stage of change, and/or IDDT itself (sometimes from previous employment outside the VA) were considered strong facilitators. Even without direct experience with IDDT practice, team members with a willingness to learn new approaches and tendency to embrace veteran-centered care were considered more “ready” to implement IDDT. Team members with a strong background in 12-step models or those less familiar with the recovery model were noted as resisting the change to IDDT:

..that traditional consequences addiction approach, where people need to suffer consequences in order for them to change...I mean these people live on the streets, they eat out of dumpsters…what else could you possibly take away from them as a consequence to get them to change?

Likewise, some nursing and other staff trained primarily in the medical model in some cases found it difficult to adapt to IDDT’s stage-wise approach where treatment strategies shift based on both symptoms and readiness to engage rather than symptoms alone. Having staff who were comfortable talking about substance use also was identified as a facilitator in the PRRC program. In a similar vein, the newer MHICM team identified needing to learn more about substance use disorders in general because their staff came from an exclusively mental health background.

Inner Setting

Inner setting facilitators varied considerably by program type, team size, and team cohesion. The two smaller teams (PRRC program Program B and MHICM Program C) were cohesive work units with a strong team culture where staff input was valued. A respondent from the PRRC program described their team’s culture as a facilitator in terms of their commitment to an implementation effort once selected: “our group is kind of a group of people that are like, ‘if we’re gonna do this, let’s do it right’.” These teams also described a strong sense of the team being veteran-centered and recovery-oriented, an important philosophical consistency with IDDT that is not universally embraced. In contrast to these smaller teams, the large HUD VASH team consisted of almost 20 clinicians who expressed varying degrees of acceptance of IDDT model philosophy, with some voicing outright resistance to treatment principles other than abstinence-only or 12-step models (e.g., stage-wise, harm reduction). A few staff on this team expressed concern during training that IDDT would pull resources away from veterans who were ready actively engaged in recovery so that they would spend more time with veterans in “denial” who continue to use. Another was skeptical of the value of motivational interventions, preferring a “harder” approach with “consequences” for relapses. To a certain extent, this was also the case early on for the larger, mature MHICM team. However, that team had an experienced team leader who was able to gently persuade the few resistant staff to “buy-in” to the stage-wise and veteran-centered mindset required by IDDT by first taking note of their concerns: “our supervisor is very good at allowing people to express their concerns … he tries to help them address those concerns and explains, and you know, helps them just process them.”

Team leaders’ confidence in the value of IDDT was also viewed as helpful for shaping implementation at the team level: “so if you have a program supervisor…that…thinks this is going to work, I think that’s helpful.” Also, a team leader’s experience with IDDT or its clinical skills or philosophies were considered facilitators. For example, two of the team leaders had experience with direct IDDT provision prior to employment at the VA, while a third had experience with staging and motivational interviewing outside the VA. The fourth was familiar with motivational interviewing. Observations revolved around the importance of having a solid foundation of the clinical and philosophical content of the model, in order to “sell” these elements. Clear and strategic leadership in communication about IDDT implementation efforts, timelines, and tools (e.g., fidelity assessments) were cited as either a valuable facilitator of implementation in the mature sites or barriers requiring improvement in the new sites.

Staffing was also a critical element of inner setting. For instance, staff turnover was a noted barrier to implementation, with a new influx of IDDT staff requiring ongoing attention to training efforts. On the other end of the spectrum, one of the more mature programs (the PRRC) also described having ample peer support specialists within the program as “a must” for engaging veterans in IDDT. Among their peer specialists, this program made a concerted effort to hire at least one with both mental health and comorbid substance use disorder who was in recovery.

Outer Setting

Themes in this domain serving as facilitators to IDDT implementation across all sites included high veteran need for IDDT in their existing program population, addressing gaps in VA services for coordinated care, and hearing about the success of other IDDT programs. Program respondents almost universally described their patient population including a high proportion of dually diagnosed veterans who needed IDDT services. All teams had at least one respondent report that well over half of their veterans were struggling with comorbid mental health and substance use disorders. For the two mature programs, proximity to national experts in IDDT was a facilitator, as was support from their service line and facility leaders. Many of the respondents on those teams had been hearing positive aspects of IDDT for some time. IDDT was also perceived by some as a potential tool to address external pressures from regional and national VA leadership. One program administrator cited IDDT’s emphasis on outreach and engagement as potentially contributing to improvements in veteran access to care, a high priority VA performance metric. The PRRC program cited improvements to their “unique encounters” performance metric as a facilitating factor. As the program began successfully engaging some consumers at the appropriate staging and thinking about the veteran’s goals for recovery, one respondent reported having a sense that the veterans were more likely to show up for appointments and improve the program’s performance on this metric. Similarly, a HUD VASH respondent felt that IDDT could be a programmatic tool to help VA “end homelessness” (a strategic priority for VA), particularly by helping veterans reduce their substance use and thereby reduce “negative exits” from the housing voucher program (a performance metric for HUD VASH programs) as a result of a substance abuse relapse.

Outer context barriers included lack of support from facility and service line leadership for some sites, detailing (e.g., reassigning the team leader away from program and not generally valuing the effort), and VA policies on staffing or procedures inconsistent with the IDDT model (e.g., no dedicated psychiatrist in PRRC or HUD VASH; no national guidelines requiring a substance abuse specialists for MHICM teams; minimal outreach capabilities for PRRC since they are designed to be office-based). In one case, there was a clear theme of feeling disconnected from the rest of the facility: “it’s just difficult to…coordinate that with other groups in the hospital. We’re not always on the same page about what’s needed.” Staff also reported policies that kept them from fully meeting veteran needs. The HUD VASH team, for example, included numerous licensed social workers trained in psychotherapy but was prohibited from providing therapy because the HUD VASH program is considered an ancillary service by national policy. This policy was interpreted in a way that kept HUD VASH social workers from providing individual and group substance abuse counseling within an integrated team, as required by IDDT model ideals.

Implementation Process

All four teams specifically noted that the implementation process for IDDT is long and requires ongoing focused attention, leadership, and coaching, with initial start-up probably taking more than 1 year. Facilitation for both of the newly implemented programs could have also been improved with more knowledge about the VA service system (a possible disadvantage for external facilitation), better engagement of service leadership at the facility, and faster movement from abstract model concepts to coaching and shadowing in actual IDDT casework. These sentiments were echoed, albeit less strongly, in the two more mature teams who had different external facilitators. Mature teams expressed a strong desire to have facilitators continue to shadow or coach them in the field in providing IDDT interventions. When asked about ideal facilitation factors, both newer and mature teams in the implementation process endorsed shadowing a more mature team in a VA setting to see how the model really looks after it “goes live.” One program leader referred to this shadowing experience as “extremely helpful.” Respondents from the two mature teams appreciated their facilitator’s handouts, visual aids, and ready to tailor forms and tracking sheets in aiding in implementation. Because staff turnover was a frequent phenomenon, the mature MHICM team also expressed a need for repeating basic IDDT training for new staff at various intervals—a single implementation event or even a year of implementation work would not meet the needs of an evolving team with new members being on-boarded frequently.

The HUDVASH team (a large team) eventually decided to implement with a small “teamlet” of 7 staff midway through the year, rather than trying to train and coach the entire team (close to 20 individuals at any given time). The team leader also focused on staff who volunteered to implement the model, rather than continue trying to convert unwilling participants. This was a modestly successful change. The two new programs eventually decided to pursue a service agreement to coordinate services between the two teams in order to complement the strengths and weaknesses of each (substance abuse specialists and housing resources of HUDVASH with the psychiatrist effort and treatment coordinator function of MHICM). The mature PRRC and MHICM teams attempted to coordinate in similar way but, according to several staff on each team, struggled to do so effectively when experiencing philosophical or staging disagreements.

Costs of IDDT Implementation Support Efforts

For the newly implementing sites, costs were estimated based on both the cost of the facilitator and lost productivity of staff participating in facilitation. For HUDVASH (Program D), 29 unique staff spent 377 staff hours ($14,634) in implementation efforts. For MHICM (Program C), 7 unique MHICM staff spent 191 staff hours ($8,739) in implementation efforts. External facilitation annualized hours were fairly constant for HUDVASH and MHICM: 69 h ($2,424) and 63 h ($2,222), respectively. When added together, the overall greater cost for HUDVASH can be attributed primarily to the larger team size taking part in training and fidelity assessment efforts. We also computed a per-FTE average implementation cost for each program, including both program staff time and facilitator time. Using an average of 18 FTE for HUDVASH for the first half of the year and 7 FTE for the second half of the year (after the change in implementation approach to target a teamlet), this resulted in costs of $1365 per person per year for HUDVASH. Using 4 FTE for MHICM, this resulted in costs of $2740 per person per year for MHICM.

Discussion

This study examined multiple programs that varied by type, size, and duration of implementation to learn more about the barriers, facilitators, and costs of implementing IDDT in routine VA care settings. Consistent with research on IDDT outside VA care settings, critical factors in implementation included leadership from both within and outside the implementing team and mastery of important skills in implementation at both the team leader and supervisory level (Brunette et al., 2008; Moser et al., 2004). Also consistent with other findings, the complexity of IDDT, as well as staff turnover, necessitated more intensive, ongoing coaching from facilitators, even beyond refresher training, to support the application of the model in practice (Brunette et al., 2008; Chandler, 2009; Kikkert et al., 2018; Moser et al., 2004; Wieder & Kruszynski, 2007; Woltmann & Whitley, 2007). Specifically, Chandler and colleagues (2009) found staff turnover to be a significant challenge to IDDT implementation efforts. Results yielded useful factors to consider in selecting and supporting programs and staff for implementation, as well as time and costs associated with implementation activities. These findings could be helpful in setting appropriate expectations for how an organization might need to support a successful implementation effort.

IDDT implementation was bolstered by the fact that most staff perceived the intervention as helpful for the population. The match between high needs of the veteran population served (outer setting) and the staging, motivational interviewing, and harm reduction components of the intervention (intervention characteristics) might be a way to make the case for implementing the program in future efforts. For instance, IDDT could be proposed as a tool to help VA programs engage, retain, and meet the needs of some of their most vulnerable veterans. Outcomes (e.g., hospitalization, substance use, negative exits from housing/housing stability) and process metrics (e.g., service access, service retention, positive veteran experiences with care) from these early adopters might also be helpful in creating the marketing package to further disseminate the model across VA—linking IDDT implementation with key VA priorities for reform, such as coordinating care more efficiently to serve complex veteran needs (VA MISSION ACT, 2018).

The complexity of the intervention and the need for ongoing coaching and instruction in the use of the model was clear. Even in the more mature IDDT programs, staff continued to want coaching during actual contacts with veterans. This is a model that is easy to talk about in the abstract but sometimes difficult to execute in practice. For instance, several respondents asked for much more concrete help from facilitators in processing how to intervene with specific veterans in early stages of change, such as those in pre-contemplation or contemplation stages. Although we had conceptualized start-up as 1 year of implementation facilitation and fidelity assessment, our contacts with the mature sites confirmed our suspicions that 2 years is probably the minimum start-up time required for IDDT, consistent with other findings (Brunette et al., 2008; Chandler, 2009; Moser et al., 2004). In our newly implementing sites, the implementation process was modified substantially midway through implementation with a re-focus on a teamlet of volunteers rather than forcing implementation on a team of roughly 20 staff, some of whom were highly skeptical of harm reduction. Based on this experience, larger teams might begin by taking this volunteer approach and building internal champions who can later help the remaining members of the team implement the model after they have had some initial success.

We noticed an interesting trade-off in the skills and backgrounds of staff implementing the model across both newly implementing teams. All teams noted that staff who were entrenched in either the 12-step or abstinence-only substance abuse treatment traditions were more likely to resist the main philosophies and principles underlying IDDT: harm reduction, stage-wise interventions focusing on engagement and reductions in use for early stage veterans, and motivational enhancement over confrontation. In many ways, staff with only a mental health background, as opposed to substance abuse treatment experience, seemed more willing to learn IDDT philosophies. Unfortunately, this also meant that several staff with a mental health background reported being “on board” with IDDT philosophy but having little knowledge and comfort with discussing substance use directly with veterans. Staff from the more mature teams reported that this comfort level took some time to develop. Skilled facilitation for implementation requires a delicate balance between providing concrete suggestions and advice to eager champions ready to implement and potentially “turning off” resistant clinicians who are slow to change their practice to match guidelines. Implementation efforts might include a pre-implementation assessment of team background in order to design specific technical assistance to address the needs of staff from these disparate backgrounds. A critical element of the inner setting is good leadership at the team level, a finding consistent with other implementation literature regarding the critical role of leadership in driving implementation efforts (McGuire et al., 2015).

The outer setting of the VA at both the facility and national level held substantial influence over team structure (technically, the inner setting). While VA has a wide variety of mental health programs and staffing (an asset), these resources introduce complexities that are unique to the VA as well. Since our study concluded, VA VISNs have also been reorganized, with new leadership in some cases, and are beginning to take interest in IDDT and other evidence-based mental health practices. Although various facilities and teams may exert some independence with how they structure teams, most closely follow the minimum national guidelines and do not add staff positions that are not required. For example, the two teams at each facility began working with one another to coordinate the provision of IDDT components across the teams, a substantial adaptation from IDDT proper where all components are provided by a single team. As an example, the PRRC team and the large MHICM team had many overlapping veterans between their programs. PRRC provided the IDDT group treatments for these veterans, a natural decision given the existing support for group psychotherapy within hospital-based PRRC programs with licensed psychologists and other therapists, while the MHICM team provided outreach and case management. This might be an example of how adaptations of IDDT may need to look for implementation without undertaking sweeping changes in national program guidelines. This is not surprising as CFIR and other implementation frameworks emphasize local adaptation as a natural and potentially beneficial part of implementation (Aarons et al., 2012; Chambers & Norton, 2016). Other recent literature also points to the importance of implementation contexts, such as social networks and organizational belonging in practice adaptions (Hoej et al., 2019). However, additional research is necessary to explore how particular adaptations impact effectiveness of the practice. For large bureaucratic services settings like VA, this may be the only way to implement IDDT components in a manageable way. Implementors may benefit from revising fidelity measurement to focus on overly restrictive, specific “forms” of IDDT and rather guide implementors toward core functions of IDDT that may be fulfilled according to local settings (Perez Jolles et al., 2019).

The two teams followed prospectively for cost identification varied widely in size. Total costs for each team’s time spent in implementation activities for the first year was less than $20,000. For the smaller team, the cost was less than $10,000, although the per staff costs for that team were double due to their small team size coupled with consistent contacts with the facilitator. Future efforts could maximize economies of scale by working jointly with multiple programs at once. Overall, in the wider context, these implementation costs are relatively modest if they offer a way to efficiently coordinate services for veterans with complex needs.

Conclusion/Impact

Because MHICM teams already have an integrated team structure, we might conclude that for VA, implementing IDDT on MHICM teams is the path of least resistance. For instance, MHICM teams should already offer comprehensive support services required by IDDT, such as psychiatry, mental health counseling, nursing, employment services, and, in many cases, peer specialists to engage veterans. MHICM teams are also equipped with the ability to perform outreach and provide intensive, frequent services, if necessary, for veterans with complex needs. The adjustment for implementing IDDT on a MHICM team might include either adding a substance abuse specialist to specifically target substance abuse assessments and counseling or conversion of an existing position to take on those duties. However, a team culture that is willing to embrace stage-wise interventions and harm reduction is another critical ingredient that cannot be sufficed by structure alone. In 2 of the study sites, critical substance abuse counseling services for individuals and groups were supported or at least enhanced by VA staff outside of a particular team (e.g., a PRRC program). In some ways, coordinating across team lines is a common strategy in VA efforts even if this detracts from an IDDT model ideal: a single, cohesive team to provide comprehensive services to veterans with dual disorders. In cases where the personnel and hospital administrative support is present, this type of adaptation may be a way to speed up implementation of care that is at least minimally integrated, if not in perfect adherence to model fidelity. As is the case with many implementation efforts, administrators may be wise to consider these recommendations but also perform their own assessment of existing programs and their “fit” with IDDT in terms of both structure, function, and philosophy. Implementation supports should include ample coaching for intervention selection and provision to meet stage-wise needs and be sustained long enough, likely 2 years or more, for team members to obtain feedback and coaching as they begin to change practice and implement required techniques.

This project will inform future efforts to implement IDDT in the VA and improve services for veterans struggling with severe mental illness and substance use disorders. IDDT addresses a critical gap in services provided to veterans with both mental health and substance use disorders but remains challenging to implement for even mature teams.

References

Aarons, G. A., Green, A. E., Palinkas, L. A., Self-Brown, S., Whitaker, D. J., Lutzker, J. R., . . . Chaffin, M. J. (2012). Dynamic adaptation process to implement an evidence-based child maltreatment intervention. Implementation Science, 7(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-32

Aarons, G. A., & Sommerfeld, D. H. (2012). Leadership, innovation climate, and attitudes toward evidence-based practice during a statewide implementation. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(4), 423–431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2012.01.018

Abram, K. M., & Teplin, L. A. (1991). Co-occurring disorders among mentally ill jail detainees. Implications for Public Policy. American Psychologist, 46(10), 1036–1045.

Alverson, H., Alverson, M., & Drake, R. E. (2000). An ethnographic study of the longitudinal course of substance abuse among people with severe mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal, 36(6), 557–569.

Bartels, S. J., Teague, G. B., Drake, R. E., Clark, R. E., Bush, P. W., & Noordsy, D. L. (1993). Substance abuse in schizophrenia: Service utilization and costs. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 181(4), 227–232. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=8473874

Bowers, M. B., Jr., Mazure, C. M., Nelson, J. C., & Jatlow, P. I. (1990). Psychotogenic drug use and neuroleptic response. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 16(1), 81–85.

Boyle, P. E., & Kroon, H. (2006). Integrated dual disorder treatment: Comparing facilitators and challenges of implementation for Ohio and the Netherlands. International Journal of Mental Health, 35(2), 70–88. https://doi.org/10.2753/IMH0020-7411350205

Brunette, M. F., Asher, D., Whitley, R., Lutz, W. J., Wieder, B. L., Jones, A. M., & McHugo, G. J. (2008). Implementation of integrated dual disorders treatment: A qualitative analysis of facilitators and barriers. Psychiatric Services, 59(9), 989–995.

Caton, C. L., Shrout, P. E., Eagle, P. F., Opler, L. A., Felix, A., & Dominguez, B. (1994). Risk factors for homelessness among schizophrenic men: A case-control study. American Journal of Public Health, 84(2), 265–270. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=8296951

Chambers, D. A., & Norton, W. E. (2016). The adaptome: Advancing the science of intervention adaptation. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 51(4), S124–S131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2016.05.011

Chandler, D. (2009). Implementation of integrated dual disorders treatment in eight California programs. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 12(4), 330–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/15487760903248473

Clark, R. E. (1994). Family costs associated with severe mental illness and substance use. Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 45(8), 808–813. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=7982698. Accessed 28 July 2022.

Damschroder, L. J., Aron, D. C., Keith, R. E., Kirsh, S. R., Alexander, J. A., & Lowery, J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-50

Dixon, L. B., Dickerson, F., Bellack, A. S., Bennett, M., Dickinson, D., Goldberg, R. W., . . . Kreyenbuhl, J. (2010). The 2009 Schizophrenia PORT psychosocial treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 36(1), 48-70. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbp115

Drake, R. E., & Bond, G. R. (2010). Implementing integrated mental health and substance abuse services. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 6(3/4), 12p. https://doi.org/10.1080/15504263.2010.540772

Drake, R. E., Essock, S. M., Shaner, A., Carey, K. B., Minkoff, K., Kola, L., . . . Rickards, L. (2001a). Implementing dual diagnosis services for clients with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 52(4), 469–476. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=11274491. Accessed 28 July 2022.

Drake, R. E., Goldman, H. H., Leff, H. S., Lehman, A. F., Dixon, L., Mueser, K. T., & Torrey, W. C. (2001b). Implementing evidence-based practices in routine mental health service settings. Psychiatric Services, 52(2), 179–182. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=11157115. Accessed 28 July 2022.

Drake, R. E., Luciano, A. E., Mueser, K. T., Covell, N. H., Essock, S. M., Xie, H., & McHugo, G. J. (2016). Longitudinal course of clients with co-occurring schizophrenia-spectrum and substance use disorders in urban mental health centers: A 7-year prospective study. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 42(1), 202–211. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbv110

Drake, R. E., Mercer-McFadden, C., Mueser, K. T., McHugo, G. J., & Bond, G. R. (1998). Review of integrated mental health and substance abuse treatment for patients with dual disorders. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 24(4), 589–608. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=9853791. Accessed 28 July 2022.

Drake, R. E., Mueser, K. T., Brunette, M. F., & McHugo, G. J. (2004). A review of treatments for people with severe mental illnesses and co-occurring substance use disorders. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 27(4), 360–374. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=15222148

Drake, R. E., O’Neal, E. L., & Wallach, M. A. (2008). A systematic review of psychosocial research on psychosocial interventions for people with co-occurring severe mental and substance use disorders. Journal of substance abuse treatment, 34(1), 123–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2007.01.011

Drake, R. E., Osher, F. C., & Wallach, M. A. (1989). Alcohol use and abuse in schizophrenia. A prospective community study. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 177(7), 408–414. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=2746194. Accessed 28 July 2022.

Drake, R. E., Xie, H., & McHugo, G. J. (2020). A 16-year follow-up of patients with serious mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorder. World Psychiatry : Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 19(3), 397–398. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20793

Edens, E. L., Kasprow, W., Tsai, J., & Rosenheck, R. A. (2011). Association of substance use and VA service-connected disability benefits with risk of homelessness among veterans. The American Journal on Addictions, 20(5), 412–419. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1521-0391.2011.00166.x

Greenfield, S., Weiss, R. D., & Tohen, M. (1995). Substance abuse and the chronically mentally ill: A description of dual diagnosis treatment services in a psychiatric hospital. Community Mental Health Journal, 31, 265–278.

Hamilton, A. (2013). Qualitative methods in rapid turn-around health services research. VA HSR&D National Cyberseminar Series: Spotlight on Women's Health. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars/archives/video_archive.cfm?SessionID=3846

Harrison, J., Cousins, L., Spybrook, J., & Curtis, A. (2017a). Peers and co-occurring research-supported interventions. Journal of Evidence-Informed Social Work, 14(3), 201–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/23761407.2017.1316220

Harrison, J., Spybrook, J., Curtis, A., & Cousins, L. (2017b). Integrated dual disorder treatment: Fidelity and implementation over time. Social Work Research, 41(2), 111–120. https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/svx002

Hartz, S. M., Pato, C. N., Medeiros, H., Cavazos-Rehg, P., Sobell, J. L., Knowles, J. A., . . . Consortium, f. t. G. P. C. (2014). Comorbidity of severe psychotic disorders with measures of substance use. JAMA Psychiatry, 71(3), 248-254. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.3726

Havassy, B., Shopshire, M., & Quigley, L. (2000). Effects of substance dependence on outcomes of patients in a randomized trial of two case management models. Psychiatric Services, 51, 639–644.

Hellerstein, D. J., Rosenthal, R. N., & Miner, C. R. (1995). A prospective study of integrated outpatient treatment for substance-abusing schizophrenic patients. American Journal on Addictions, 4(1), 33–42.

Ho, A., Tsuang, J., & Liberman, R. (1999). Achieving effective treatment of patients with chronic psychotic illness and comorbid substance dependence. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156, 1765–1770.

Hoej, M., Johansen, K. S., Olesen, B. R., & Arnfred, S. (2019). Negotiating the practical meaning of recovery in a process of implementation. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-019-00993-4

Hunt, G. E., Large, M. M., Cleary, M., Lai, H., & Saunders, J. B. (2018). Prevalence of comorbid substance use in schizophrenia spectrum disorders in community and clinical settings, 1990–2017: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 191, 234–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.07.011

Hunt, G. E., Malhi, G. S., Cleary, M., Lai, H. M. X., & Sitharthan, T. (2016). Prevalence of comorbid bipolar and substance use disorders in clinical settings, 1990–2015: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 206, 331–349.

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Crossing the Quality Chasm: Adaptation to Mental Health and Addictive Disorders. Improving the quality of health care for mental and substance-use conditions: Quality chasm series. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2006. Appendix C, Mental and Substance-Use Health Services for Veterans: Experience with Performance Evaluation in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK19834/

Kessler, R. C., Chiu, W. T., Demler, O., Merikangas, K. R., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 617–627. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617

Kikkert, M., Goudriaan, A., De Waal, M., Peen, J., & Dekker, J. (2018). Effectiveness of Integrated Dual Diagnosis Treatment (IDDT) in severe mental illness outpatients with a co-occurring substance use disorder. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 95, 35–42.

McGuire, A. B., Salyers, M. P., White, D. A., Gilbride, D. J., White, L. M., Kean, J., & Kukla, M. (2015). Factors affecting implementation of an evidence-based practice in the Veterans Health Administration: Illness management and recovery. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 38(4), 300–305. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000116

McHugo, G. J., Drake, R. E., Teague, G. B., & Xie, H. (1999). Fidelity to assertive community treatment and client outcomes in the New Hampshire Dual Disorders Study. Psychiatric Services, 50(6), 818–824.

Mercer-McFadden, C., Drake, R. E., & Brown, N. B. (1997). The community support program demonstrations of services for young adults with severe mental illness and substance use disorders, 1987–1991. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 20(3), 13–24.

Moser, L. L., DeLuca, N. L., Bond, G. R., & Rollins, A. L. (2004). Implementing evidence-based psychosocial practices: Lessons learned from statewide implementation of two practices. CNS Spectrums, 9(12), 926-936,942. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852900009780

Mueser, K., Drake, R., & Noordsy, D. (1998). Integrated mental health and substance abuse treatment for severe psychiatric disorders. Journal of Practical Psychiatry and Behavioral Health, 4, 129–139.

Mueser, K. T., Yarnold, P. R., & Bellack, A. S. (1992). Diagnostic and demographic correlates of substance abuse in schizophrenia and major affective disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 85, 48–55.

Mueser, K. T., Yarnold, P. R., Rosenberg, S. D., Swett, C., Miles, K. M., & Hill, D. (2000). Substance use disorder in hospitalized severely mentally ill psychiatric patients: Prevalence, correlates, and subgoups. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 26, 179–192.

Osher, F. C., Drake, R. E., Noordsy, D. L., Teague, G. B., Hurlbut, S. C., Biesanz, J. C., & Beaudett, M. S. (1994). Correlates and outcomes of alcohol use disorder among rural outpatients with schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 55(3), 109–113.

Perez Jolles, M., Lengnick-Hall, R., & Mittman, B. S. (2019). Core functions and forms of complex health interventions: A patient-centered medical home illustration. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 34(6), 1032–1038. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4818-7

Petrakis, I. L., Rosenheck, R., & Desai, R. (2011). Substance use comorbidity among veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder and other psychiatric illness. The American Journal on Addictions, 20(3), 185–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1521-0391.2011.00126.x

Ridgely, M. S., Osher, F., & Talbott, J. (1987). Chronic mentally ill young adults with substance abuse problems: Treatment and training issues. University of Maryland Department of Psychiatry.

Rosenberg, S. D., Goodman, L. A., Osher, F. C., Swartz, M. S., Essock, S. M., Butterfield, M. I., Constantine, N. T., Wolford, G. L., & Salyers, M. P. (2001). Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C in people with severe mental illness. American Journal of Public Health, 91(1), 31–37.

Stein, L. I., & Test, M. A. (1980). An alternative to mental health treatment. I: Conceptual model, treatment program, and clinical evaluation. Archives of General Psychiatry, 37, 392–397.

Tsemberis, S., & Eisenberg, R. F. (2000). Pathways to housing: Supported housing for street-dwelling homeless individuals with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services, 51(4), 487–493.

VA Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks Act of 2018, Pub. L. No. 115–182. U. S. C. § 2372. (2018). https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/PLAW-115publ182

Wieder, B. L., & Kruszynski, R. I. C. (2007). The salience of staffing in IDDT implementation: One agency’s experience. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 10(2), 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/15487760701346016

Woltmann, E. M., & Whitley, R. (2007). The role of staffing stability in the implementation of integrated dual disorders treatment: An exploratory study. Journal of Mental Health, 16(6), 757–769. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638230701496402

Zivin, K., Bohnert, A. S., Mezuk, B., Ilgen, M. A., Welsh, D., Ratliff, S., . . . Kilbourne, A. M. (2011). Employment status of patients in the VA health system: Implications for mental health services. Psychiatr Serv, 62(1), 35-38. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.62.1.35

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the study participants for making this work possible. Views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government.

Funding

This work was funded by the VA Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) RRP 12–504 (PI: Rollins). Drs. Rollins, Eliacin, Kukla, and McGuire were also supported in part by the VA Health Services Research and Development (HSR&D) Center for Health Information and Communication, CIN 13–416. Dr. Eliacin was supported in part by a VA HSR&D Career Development Awards: CDA 16–153 (PI: Eliacin).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors followed the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR).

Ethics Approval

All human subject procedures in this study were approved by the Indiana University Institutional Review Board, as well the VA Research and Development Committee of the Richard L. Roudebush VA Medical Center.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Rollins, A.L., Eliacin, J., Kukla, M. et al. Implementation of Integrated Dual Disorder Treatment in Routine Veterans Health Administration Settings. Int J Ment Health Addiction 22, 578–598 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-022-00891-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-022-00891-1