Abstract

We characterized suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among incarcerated people in Iran. We recruited a multistage random sample of 5785 incarcerated people from 33 prisons across Iran. Eligible participants were those aged ≥ 18 years who had been incarcerated for at least one week at the time of the study. Lifetime suicidal ideation and suicide attempts were estimated at 38.2% and 20.5%, respectively. Of participants who reported suicide attempts, 57.6% reported attempts prior to incarceration, 31.5% while incarcerated, and 10.9% both before and during incarceration. Suicide attempt was significantly associated with a younger age, being a woman, being widowed/divorced, a longer period of incarceration, convictions for violent crimes, HIV sero-positivity, lifetime non-injection, and injection drug use. The primary reasons reported for suicide attempts were feeling empty/hopeless and living with substance use disorders. Prison health services should provide a comprehensive, integrated mental health programme, including mental health screening upon arrival and continued care during incarceration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Incarcerated people are at a disproportionate risk of suicide compared to those in the general population due to a range of social, environmental, and mental health–related factors (e.g. psychiatric illness, substance use disorders, childhood maltreatment, family conflict, social isolation, and repetitive self-harm) (Fazel et al., 2013; Fruehwald et al., 2004; Shaw et al., 2004; Zhong et al., 2020). Additionally, encounters with the criminal justice system as well as risk factors associated with incarceration, such as convictions for a violent crime, feelings of guilt, serving a life sentence, solitary confinement, and having no social or conjugal visits, increase the risk of suicide among incarcerated people (Blaauw et al., 2005; Fazel et al., 2017; Zhong et al., 2020). Suicide risk also varies greatly by gender. For example, studies in England and Wales show that suicide rates are five to six times higher among incarcerated men than the general population (Fazel et al., 2005), and are 20 times higher among incarcerated women than those in the general community (Fazel & Benning, 2009). In addition, the prevalence of severe mental illness is higher among incarcerated people in low- and middle-income countries than those incarcerated in high-income countries (Baranyi et al., 2019; Fazel & Seewald, 2012).

An increasing body of evidence among the general Iranian population suggests an increasing trend of fatal suicide in the past few decades (Daliri et al., 2017; Naghavi et al., 2014; Nazarzadeh et al., 2013). For example, suicide rates between 2006 and 2015 increased from 5.99 to 6.73 per 100,000 people in men and from 2.41 to 2.64 per 100,000 people in women (Izadi et al., 2018). As of 2016, the average number of incarcerated people in Iran is 225,000 (3.1% women) (Walmsley, 2016), and most are incarcerated for drug-related crimes and convictions (Nikpour, 2019). Indeed, incarcerated people have been identified as one of the key populations at risk for contracting HIV in Iran (Navadeh et al., 2013), and 70–90% have a history of non-injection drug use and 15–40% have ever injected drugs (Mirzazadeh et al., 2018; Moradi et al., 2020; Zamani et al., 2010). Despite the growing evidence on HIV and drug use practices among incarcerated people in Iran, there is a knowledge gap about their mental health outcomes, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts. Indeed, no previous study has examined suicide-related outcomes among incarcerated people in Iran. This study aimed to use data from a nationwide bio-behavioural surveillance survey and assess the prevalence and correlates of suicidal ideation and suicide attempt among a nationally representative sample of incarcerated women and men in Iran. Understanding the risk factors and reasons behind suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among incarcerated people would help policymakers, public health practitioners, and prison health services to provide better mental health services and improve incarcerated people’s access to mental health care.

Methods

Study Design and Sampling

This study is a secondary analysis of data collected through the most recent national bio-behavioural surveillance survey of incarcerated people in Iran, conducted between January and March 2017. Using a multistage random sampling approach, we enrolled 5785 incarcerated people from 33 prisons across the country (Fig. 1). Participants were recruited in the survey if they were ≥ 18 years old, had been incarcerated for at least one week at the time of the study, and held Iranian citizenship.

We first categorized prisons into large and small strata based on the median number of incarcerated people. We randomly selected 17 and 16 prisons from the small and large prison strata, respectively. Next, the required number of samples in each prison was determined based on the ratio of the prison population in each prison to the total prison population. We also determined the sample of men and women in each prison based on the ratio of the men and women in prison to the total number of incarcerated people. Finally, the required number of incarcerated people in each prison was included in the study using a systematic random sampling technique. The recruited sample of small prisons ranged between 60 and 150, and large prisons ranged between 155 and 365.

Data Collection

We obtained verbal informed consent for both the interview and HIV testing. A trained, gender-matched interviewer conducted face-to-face interviews using a standardized risk assessment questionnaire. The study questionnaire was in Farsi and included sections on sociodemographic data, history of incarceration, sexual behaviours, HIV status, drug use and injection practices, and suicidal behaviours. The questionnaire was validated in previous surveys among incarcerated people in Iran in 2010 and 2013 (Navadeh et al., 2013). After the interviews, HIV testing and counselling were provided. HIV testing was performed by SD BIOLINE HIV rapid test and, if reactive, was confirmed by Uni-Gold HIV rapid test.

Study Variables

Dependent Variables: Suicidal Ideation and Suicide Attempt

Self-reported lifetime suicidal ideation and suicide attempts were the primary outcomes. Participants were asked, “In your lifetime, have you had any serious thoughts, considerations, or plans about attempting suicide or taking your life?” with the following response options: yes vs. no. Participants were also asked, “In your lifetime, have you ever attempted any potentially self-harming behaviour to take your own life?” with the following response options: yes vs. no. Participants were also asked an additional question about their time of suicide attempt: “If you attempted suicide, when did you attempt suicide?” with the following response options: prior to incarceration, while incarcerated, or both before and during incarceration.

Covariates

We examined the prevalence and correlates of suicidal ideation and suicide attempt among the total sample and separately for women and men. Covariates of interest included a range of sociodemographic variables, including age group, gender, marital status, educational level, and HIV status. Drug use-related risk factors included lifetime non-injection and injection drug use. Incarceration history variables included prior incarcerations (none [i.e. first time in prison], once before, or multiple [i.e. several times before]), duration of incarceration, and convictions for violent crimes, such as homicide, rape, and armed robbery (Sarchiapone et al., 2009).

Self-reported Reasons for Suicide Attempt

We also asked participants about their reasons for suicide attempts. Respondents who reported suicide attempts in their lifetime were asked, “What were the reasons for your most recent suicide attempt?” with options, such as being incarcerated, feeling empty/hopeless, substance use disorders, rejection from the family, bankruptcy, poverty, and spousal betrayal. Respondents could choose more than one reason and were encouraged to elaborate with a free-text response if they had any other reasons to share.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics of the main study outcomes and other variables were calculated and reported. We compared the prevalence of the study outcomes across subgroups of independent covariates using chi-square tests for the overall study sample, and stratified by gender. Multivariable logistic regression was used to examine the correlates of suicide attempts among the full sample and separately for men and women. Covariates with a p-value < 0.2 were entered into the multivariable regression models (Maldonado & Greenland, 1993), and p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported. All analyses were conducted in Stata v.15.

Ethical Consideration

Ethical issues included the guarantee of the participants’ confidentiality using anonymous questionnaire tools and obtaining verbal informed consent for both biological and behavioural data collection procedures. Participants’ receipt of health care services was not impacted by their willingness to participate in the study. The ethics committee of the Kerman University of Medical Sciences approved the study protocol (Ethics Code: IR.KMU.REC.1394.609).

Results

Sample Characteristics

Among 5785 recruited incarcerated people, 350 (6.1%) were women, and the mean age (SD) was 35.7 (12.2) years. Most participants were married (50.8%; n = 2939) and had an educational level less than high school (68.9%; n = 3977). Over one-third of the participants had experienced multiple incarcerations (37.2%; n = 2144), about one-fourth had been incarcerated for ≥ 5 years (25.1%; n = 850), and 16.1% (n = 927) had been convicted for violent crimes. Lifetime non-injection and injection drug use were reported by 76.5% (n = 4424) and 12.2% (n = 705), respectively. The prevalence of HIV was 0.9% (95% CI: 0.6, 1.1) (Table 1).

Prevalence of Suicide Ideation and Attempt

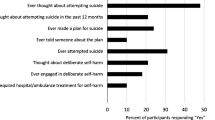

Overall, 2207 participants (38.2%, 95% CI: 36.9, 39.4) self-reported ever having had suicidal ideation, and 1185 participants (20.5%, 95% CI: 19.5, 21.6) reported at least one suicide attempt in their lifetime. Of incarcerated people who reported previous suicide attempts, 682 (57.6%) reported a suicide attempt prior to incarceration, 373 (31.5%) had made a suicide attempt while incarcerated, and 129 (10.9%) made suicide attempts both before and during incarceration. A significantly higher prevalence of suicidal ideation was reported among incarcerated women than incarcerated men (46.3% vs. 37.7%; p = 0.001). Suicide attempt was also significantly higher among incarcerated women than men (28.3% vs. 20.0%; p < 0.001) (Fig. 2).

Suicidal Ideation Across Subgroups

Overall, a significantly higher prevalence of suicidal ideation was reported among incarcerated people who were younger (43.1% for < 25 years vs. 34.6% for ≥ 35 years; p < 0.001), were widowed/divorced (47.5% vs. 42.1%; p < 0.001), had less than high school education (39.4% vs. 35.6%; p = 0.007), experienced multiple incarcerations (48.2% vs. 30.8%; p < 0.001), were incarcerated for ≥ 5 years (52.1% vs. 36.3%; p < 0.001), were convicted for violent crimes (42.1% vs. 37.5%; p = 0.008), were HIV-positive (62.0% vs. 38.0%; p = 0.001), ever used drugs (43.0% vs. 22.4%; p < 0.001), and ever injected drugs (62.8% vs. 34.8%; p < 0.001). Similar results were observed among men and women participants in separate analyses, except for marital status, prior incarceration, duration of incarceration, conviction for violent crime, HIV status, and history of drug injection, that they were not statistically significant at 0.05 level among women (Table 1).

Suicide Attempt Across Subgroups

A significantly higher prevalence of suicide attempt was reported among incarcerated people who were younger (25.5% for < 25 years vs. 16.9% for ≥ 35 years; p < 0.001), were widowed/divorced (27.3% vs. 23.7%; p < 0.001), had less than high school education (21.4% vs. 18.5%; p = 0.010), experienced multiple incarcerations (30.7% vs. 12.6%; p < 0.001), were incarcerated for ≥ 5 years (34.0% vs. 19.1%; p < 0.001), were convicted for violent crime (22.9% vs. 20.1%; p = 0.049), were HIV-positive (52.0% vs. 20.2%; p < 0.001), ever used drugs (24.3% vs. 8.2%; p < 0.001), and ever injected drugs (41.7% vs. 17.6%; p < 0.001). Similar results were also observed among men and women participants in separate analyses of suicide attempt, except for marital status, education, duration of incarceration, conviction for violent crimes, and HIV status, which were not statistically significant among women (Table 2).

Factors Associated with Suicide Attempt

In the multivariable logistic regression model, being younger than 25 years (aOR: 3.66; 95% CI: 2.63, 5.09), being a woman (aOR: 2.41; 95% CI: 1.64, 3.55), being widowed/divorced marital status (aOR: 1.36; 95% CI: 1.07, 1.72), a longer duration of incarceration (aOR: 2.06; 95% CI: 1.64, 2.58), convictions for violent crime (aOR: 1.63; 95% CI: 1.28, 2.07), HIV sero-positivity (aOR: 2.18; 95% CI: 1.13, 4.20), non-injection drug use (aOR: 3.17; 95% CI: 2.25, 4.47), and drug injection (aOR: 2.29; 95% CI: 1.87, 2.80) were significantly and positively associated with suicide attempt. Similarly, these variables were significantly associated with suicide attempts among men participants. However, among women, the multivariable model showed that only being younger than 25 years (aOR: 3.31; 95% CI: 1.30, 8.45), convictions for violent crimes (aOR: 3.15; 95% CI: 1.41, 7.01), and non-injection drug use (aOR: 4.81; 95% CI: 2.66, 8.68) were significantly associated with suicide attempt (Table 3).

Self-reported Reasons for Suicide Attempt

Of the 1185 participants who reported suicide attempts, 1158 (97.7%) provided reasons for their suicide attempts. Feeling empty/hopeless (30.2%; n = 350) and living with substance use disorders (26.5%; n = 307) were the most commonly reported reason for suicide attempt. Additional reasons included being incarcerated (20.9%; n = 242), rejection from the family (17.5%; n = 203), bankruptcy (8.4%; n = 97), living in poverty (8.2%; n = 96), and spousal betrayal (2.5%; n = 29). Individuals who reported a suicide attempt inside prison reported a higher prevalence of being incarcerated as a reason for attempting suicide than those who reported suicide attempts outside prison (45.5% vs. 2.4%; p < 0.001). Among participants who reported suicide attempts outside prison, living with substance use disorder (31.8% vs. 19.4%; p < 0.001) and spousal betrayal (3.9% vs. 0.6%; p < 0.001) were more frequently reported as reasons for attempting suicide (Table 4).

Discussion

We found that over one-third of incarcerated people in Iran reported lifetime suicidal ideation, and one-fifth reported lifetime suicide attempts. More than half of those who experienced suicide attempts reported suicide attempts before incarceration. Although the scarcity of data on suicide statistics among incarcerated populations in the Eastern Mediterranean region makes it challenging to compare these estimates with regional numbers, our findings are comparable with an international body of evidence in Australia (33.7% suicidal ideations and 20.5% suicide attempts) and Belgium (43.1% suicidal ideations and 20.3% suicide attempts) (Favril et al., 2017; Larney et al., 2012). Multivariable analysis showed that being younger than 25 years, being a woman, being widowed/divorced marital status, longer duration of incarceration, convictions for violent crimes, HIV sero-positivity, and non-injection and injection drug use were significantly associated with suicide attempts. Additionally, feeling empty/hopeless and living with substance use disorders were reported as the main reasons for suicide attempts by incarcerated people in Iran.

The considerable prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among incarcerated people in Iran underscores the need for effective mental health services, including suicide prevention programmes for this population. This is particularly important given the significant association of suicide attempts with future attempts and suicide commitments (Favril et al., 2017; Hales et al., 2015). However, mental health services in Iran have not been optimally developed; services are primarily hospital- or office-based, and the number of psychiatrists (1.49/100,000 people) and psychologists (2.19/100,000) is insufficient (Sharifi et al., 2015). Despite the need for a comprehensive approach to suicide prevention, including evidence-informed programmes, practices, and policies, there are no comprehensive mental health programmes within the prison settings in Iran. Based on the available data, the number of incarcerated people who received mental health services is small and calls for further investments (e.g. less than 20% of prisons have at least one client per month in treatment contact with a mental health professional) (WHO Country Office in the Islamic Republic of Iran, 2006).

We found that more than half of suicide attempts occurred outside prison. This supports the findings of previous studies advocating for screening of suicide risk pre-reception in the criminal justice system and upon arrival in prison (Humber et al., 2011; Marzano et al., 2016). Studies support using suicide screening tools and checklists at reception asking about suicidal ideation, hopelessness, psychiatric disorders, family history of suicide, poor social support, and previous self-harm experiences or suicide attempt to help recognize high-risk groups who would benefit from particular mental health interventions (Marzano et al., 2016). Moreover, these high-risk groups should be consistently assessed by a mental health specialist and have access to mental health services during incarceration (Humber et al., 2011). Consistent with previous research, our study showed that suicide attempts are significantly higher among incarcerated women than men (Fazel & Benning, 2009; Fazel et al., 2017; Larney et al., 2012). Prevention programmes to reduce the risk of suicide among incarcerated people in Iran’s prison health system should consider the gendered nature of suicide in their planning, and implement gender-specific approaches. For example, suicide screening checklists for women should be more comprehensive and include factors, such as children’s custody status, incarceration for violent crimes, and experiences of the loss of a partner or child (Marzano et al., 2016).

The reasons for the increased risk of suicide attempts for incarcerated people are complicated. When asked for their reasons for previous suicide attempts, participants primarily reported feeling empty/hopeless and living with substance use disorders. Our data also showed that non-injection and injection drug use were associated with suicidal ideation and suicide attempts, findings that are consistent with previous research (Andersen, 2004; Fazel et al., 2013; Lekka et al., 2006). Evidence suggests that therapeutic interventions targeting hopelessness and impulsive behaviours (e.g. cognitive behavioural therapy) in prisons could positively reduce suicide and self-harms among this population (Marzano et al., 2016; Miller, 2019). Associations between suicide-related behaviours and drug use indicators also highlight the need for in-prison screening for mental health and substance use disorders among incarcerated people, as well as investing in their prevention and treatment. Indeed, opioid agonist therapy has been shown to decrease the risk of both natural and unnatural deaths, including suicide among incarcerated people (Larney et al., 2014). Despite the achievement of opioid agonist therapy in reducing drug-related harms in prisons in Iran, it often overlooks the psychological problems of people who use drugs (Moradi et al., 2015). Although mental health services are not a routine part of harm reduction programmes in Iran, prevention programmes could target this high-risk population with more comprehensive approaches through combined or integrated programmes. Therefore, mental health services need to be included as a component of a comprehensive harm reduction approach both inside and outside prison.

Our multivariable model also showed that consistent with the literature elsewhere (Zhong et al., 2020), a longer duration of incarceration and convictions for violent crimes were associated with suicide attempt. A systematic review of factors associated with suicide attempts in prison settings suggests that incarcerated people serving a life sentence are about four times more likely to attempt suicide (Fazel et al., 2013). Moreover, several studies demonstrate that violent offenders are at an elevated risk of suicide compared to their non-violent peers (Favril, 2019; Fazel et al., 2008; Sarchiapone et al., 2009). These findings underscore the importance of active risk assessment, and identification of incarcerated people most at risk of suicide (Marzano et al., 2016). There is also a need to ameliorate environmental adversities associated with suicide (Marzano et al., 2016). For example, empowering incarcerated people’s social support networks via facilitation of opportunities for quality visits by family and friends has been proven helpful (Favril et al., 2017). Lastly, due to Iran’s war on drugs policy, over half of the incarcerated people are serving time for drug-related crimes (Nikpour, 2019). Reducing the flow of people into prisons and increasing the flow of non-violent people (e.g. those with minor drug offences) out of prisons could help reduce the burden of mental health problems and suicidal behaviours inside prisons.

Limitations

Several limitations must be considered when interpreting our findings. First, the cross-sectional design of the survey limits causal inferences of the observed associations. Second, suicide-related behaviours were self-reported and collected using face-to-face interviews by trained prison health staff, which may be subject to recall, social desirability, and underreporting biases. Third, we studied suicide as part of a survey on HIV risk and vulnerability; therefore, we only asked questions about suicide ideation and attempts and underlying reasons for such practices instead of utilizing a standard tool to evaluate suicide and its related mental disorders. Lastly, we did not measure and include some known influencing risk factors of suicide attempts, such as mental health issues, in the analysis as indicators related to suicide were examined as part of a broader survey on HIV risk and vulnerability, and there was limited space to study mental disorders comprehensively. If data had been collected, it is expected that a history of mental disorders would have been significantly associated with suicide ideation and attempts as previously reported in a considerable body of evidence (Favril et al., 2017; Zhong et al., 2020).

Conclusion

Our study showed that incarcerated people are a high-risk group for suicide in Iran and must be considered a priority target population for suicide prevention programmes. Our data suggest that the improved management of incarcerated people with mental illness, drug use, and long-term sentences, especially after violent crimes, may help minimize suicide risks. Our findings collectively underscore the need for a comprehensive mental health care programme inside prisons in Iran that includes targeted suicide prevention interventions, including screening, detection, and management of suicide risks. Integrating mental health programmes into substance use harm reduction programmes in prisons is also warranted.

Data Availability

Data are owned by the Ministry of Health (MOH) of Iran and are available from the HIV/STI office located at Iran’s MOH (e-mail: aids@behdasht.gov.ir) for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data. The authors of this research were the implementers of the survey and had access to the data with permission obtained from the MOH’s HIV/STI office.

References

Andersen, H. S. (2004). Mental health in prison populations. A review–With special emphasis on a study of Danish prisoners on remand. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 110, 5–59.

Baranyi, G., Scholl, C., Fazel, S., Patel, V., Priebe, S., & Mundt, A. P. (2019). Severe mental illness and substance use disorders in prisoners in low-income and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence studies. The Lancet Global Health, 7(4), e461–e471.

Blaauw, E., Kerkhof, A. J., & Hayes, L. M. (2005). Demographic, criminal, and psychiatric factors related to inmate suicide. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 35(1), 63–75.

Daliri, S., Bazyar, J., Sayehmiri, K., Delpisheh, A., & Sayehmiri, F. (2017). The incidence rates of suicide attempts and successful suicides in seven climatic conditions in Iran from 2001 to 2014: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific Journal of Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences, 21(6), 1–15.

Favril, L. (2019). Non-suicidal self-injury and co-occurring suicide attempt in male prisoners. Psychiatry Research, 276, 196–202.

Favril, L., Vander Laenen, F., Vandeviver, C., & Audenaert, K. (2017). Suicidal ideation while incarcerated: Prevalence and correlates in a large sample of male prisoners in Flanders, Belgium. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 55, 19–28.

Fazel, S., & Benning, R. (2009). Suicides in female prisoners in England and Wales, 1978–2004. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 194(2), 183–184.

Fazel, S., & Seewald, K. (2012). Severe mental illness in 33 588 prisoners worldwide: Systematic review and meta-regression analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 200(5), 364–373.

Fazel, S., Benning, R., & Danesh, J. (2005). Suicides in male prisoners in England and Wales, 1978–2003. The Lancet, 366(9493), 1301–1302.

Fazel, S., Cartwright, J., Norman-Nott, A., & Hawton, K. (2008). Suicide in prisoners: A systematic review of risk factors. The Journal of clinical psychiatry.

Fazel, S., Wolf, A., & Geddes, J. R. (2013). Suicide in prisoners with bipolar disorder and other psychiatric disorders: A systematic review. Bipolar Disorders, 15(5), 491–495.

Fazel, S., Ramesh, T., & Hawton, K. (2017). Suicide in prisons: An international study of prevalence and contributory factors. The Lancet Psychiatry, 4(12), 946–952.

Fruehwald, S., Matschnig, T., Koenig, F., Bauer, P., & Frottier, P. (2004). Suicide in custody: Case–control study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 185(6), 494–498.

Hales, H., Edmondson, A., Davison, S., Maughan, B., & Taylor, P. J. (2015). The impact of contact with suicide-related behavior in prison on young offenders. Crisis.

Humber, N., Hayes, A., Senior, J., Fahy, T., & Shaw, J. (2011). Identifying, monitoring and managing prisoners at risk of self-harm/suicide in England and Wales. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 22(1), 22–51.

Izadi, N., Mirtorabi, S. D., Najafi, F., Nazparvar, B., Kangavari, H. N., & Nazari, S. S. H. (2018). Trend of years of life lost due to suicide in Iran (2006–2015). International Journal of Public Health, 63(8), 993–1000.

Larney, S., Topp, L., Indig, D., O’driscoll, C., & Greenberg, D. (2012). A cross-sectional survey of prevalence and correlates of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among prisoners in New South Wales. Australia. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 1–7.

Larney, S., Gisev, N., Farrell, M., Dobbins, T., Burns, L., Gibson, A., Kimber, J., & Degenhardt, L. (2014). Opioid substitution therapy as a strategy to reduce deaths in prison: Retrospective cohort study. BMJ open, 4(4), e004666.

Lekka, N. P., Argyriou, A. A., & Beratis, S. (2006). Suicidal ideation in prisoners: Risk factors and relevance to suicidal behaviour. A prospective case–control study. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 256(2), 87–92.

Maldonado, G., & Greenland, S. (1993). Simulation study of confounder-selection strategies. American Journal of Epidemiology, 138(11), 923–936.

Marzano, L., Hawton, K., Rivlin, A., Smith, E. N., Piper, M., & Fazel, S. (2016). Prevention of suicidal behavior in prisons. Crisis.

Miller, R. (2019). Predicting dynamic risk factors for suicide ideation in prisoners: Perceived entrapment and goal management in the context of the IMV model https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10083374/1/Miller_10083374_thesis_sig-removed.pdf. Accessed 14 Dec 2021.

Mirzazadeh, A., Shokoohi, M., Navadeh, S., Danesh, A., Jain, J. P., Sedaghat, A., Farnia, M., & Haghdoost, A. (2018). Underreporting in HIV-related high-risk behaviors: Comparing the results of multiple data collection methods in a behavioral survey of prisoners in Iran. The Prison Journal, 98(2), 213–228.

Moradi, G., Farnia, M., Shokoohi, M., Shahbazi, M., Moazen, B., & Rahmani, K. (2015). Methadone maintenance treatment program in prisons from the perspective of medical and non-medical prison staff: A qualitative study in Iran. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 4(9), 583.

Moradi, G., Darvishi, S., Asaadi, L., Zavareh, F. A., Gouya, M.-M., Tashakorian, M., Alasvand, R., & Bolbanabad, A. M. (2020). Patterns of drug use and related factors among prisoners in Iran: Results from the national survey in 2015. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 41(1), 29–38.

Naghavi, M., Shahraz, S., Sepanlou, S. G., Dicker, D., Naghavi, P., Pourmalek, F., Mokdad, A., Lozano, R., Vos, T., & Asadi-Lari, M. (2014). Health transition in Iran toward chronic diseases based on results of Global Burden of Disease 2010. Archives of Iranian Medicine, 17(5), 321–35.

Navadeh, S., Mirzazadeh, A., Gouya, M. M., Farnia, M., Alasvand, R., & Haghdoost, A.-A. (2013). HIV prevalence and related risk behaviours among prisoners in Iran: Results of the national biobehavioural survey, 2009. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 89(Suppl 3), iii33–iii36.

Nazarzadeh, M., Bidel, Z., Ayubi, E., Asadollahi, K., Carson, K. V., & Sayehmiri, K. (2013). Determination of the social related factors of suicide in Iran: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 1–9.

Nikpour, G. (2019). Drugs and drug policy in the Islamic Republic of Iran. Middle East Briefs, 119, 2–7.

Sarchiapone, M., Carli, V., Giannantonio, M. D., & Roy, A. (2009). Risk factors for attempting suicide in prisoners. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 39(3), 343–350.

Sharifi, V., Amin-Esmaeili, M., Hajebi, A., Motevalian, A., Radgoodarzi, R., Hefazi, M., & Rahimi-Movaghar, A. (2015). Twelve-month prevalence and correlates of psychiatric disorders in Iran: The Iranian Mental Health Survey, 2011. Archives of Iranian Medicine, 18(2), 76–84.

Shaw, J., Baker, D., Hunt, I. M., Moloney, A., & Appleby, L. (2004). Suicide by prisoners: National clinical survey. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 184(3), 263–267.

Walmsley, R. (2016). World prison population list (11th edn). ICPS. In.

WHO Country Office in the Islamic Republic of Iran. (2006). A report of the assessment of the mental health system in the Islamic Republic of Iran using the World Health Organization - Assessment Instrument for Mental Health Systems (WHO-AIMS). https://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/who_aims_report_iran.pdf. Accessed 14 Dec 2021.

Zamani, S., Farnia, M., Torknejad, A., Alaei, B. A., Gholizadeh, M., Kasraee, F., Ono-Kihara, M., Oba, K., & Kihara, M. (2010). Patterns of drug use and HIV-related risk behaviors among incarcerated people in a prison in Iran. Journal of Urban Health, 87(4), 603–616.

Zhong S, Senior M, Yu R, Perry A, Hawton K, Shaw J, Fazel S. (2021). Risk factors for suicide in prisons: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 6(3):e164–74.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the study participants for their time, as well as the research staff and stakeholders at national and local organizations for their assistance in the survey's preparation and implementation.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this specific paper. The project was supported by the Center for Communicable Disease Control and Prevention of Iran Ministry of Health and Medical Education (Ministry of Health Grant number: 95000309). MK is supported by a Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MKH, HSH, AM, MSH, and MK conceptualized the study and developed the aims, design, and data analysis. MKH performed the data analysis. MKH and MK drafted the manuscript. SHH, SM, NGH, FM, MM, and FT collected data. All authors reviewed and edited the final manuscript and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

Ethical issues included the guarantee of the participants’ confidentiality using anonymous questionnaire tools and obtaining verbal informed consent for both biological and behavioural data collection procedures. Participants’ receipt of health care services was not impacted by their willingness to participate in the study. The ethics committee of the Kerman University of Medical Sciences approved the study protocol (Ethics Code: IR.KMU.REC.1394.609).

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Khezri, M., Sharifi, H., Mirzazadeh, A. et al. A National Study of Suicidal Ideation and Suicide Attempt Among Incarcerated People in Iran. Int J Ment Health Addiction 21, 3043–3060 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-022-00773-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-022-00773-6