Abstract

Emerging adults show higher prevalence of harmful risk behaviors, such as alcohol use and gambling, compared to other age groups. In existing research, it appears that patterns of risk behaviors vary by gender during emerging adulthood. However, scarce research has examined gender differences in prospective relations among risk behaviors in emerging adults. This study explores gender differences in the developmental risks of depression, antisocial behavior, and alcohol use (Wave III) on gambling (Waves III and IV) in emerging adulthood in a sample of emerging adults (N = 8282) from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health. Results showed that antisocial behavior was associated with increased risk of alcohol use. Heavy drinking in early emerging adulthood was associated with increased risk of gambling later, but depression was marginally protective of gambling. Among men, contemporaneous associations between alcohol use and heavy drinking were stronger than among women. Among women, earlier binge drinking conferred increased risk of later gambling problems, but in men negative relationships between the two were found. The results highlight the importance of ongoing efforts in early prevention and intervention for the co-occurrence of risk behaviors in emerging adulthood.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Involvement in risk behaviors such as alcohol use and gambling is considered to be one of the hallmarks of emerging adulthood (Sussman and Arnett 2014). Those ages 18–25 show a higher prevalence of gambling and alcohol use including past-month alcohol use (57.1 versus 54.6%), binge drinking (38.4 versus 24.2%), heavy drinking (10.1 versus 6.0%), and alcohol use disorder (10.7 versus 5.2%) compared with those over age 25 years old (Ahrnsbrak et al. 2017). By the time emerging adults reach age 29, a vast majority (95%) have engaged in some form of gambling and approximately 8% will have experienced a gambling-related problem by that time (Slutske et al. 2003). Serious involvement of alcohol use and gambling in emerging adulthood can lead to short- and long-term adverse consequences including psychological symptoms, behavioral problems, and socioeconomic and medical costs (Blinn-Pike et al. 2010).

Alcohol, depression, and antisocial behavior have been hypothesized as important precursors to the development of gambling disorder (Blaszczynski and Nower 2002). Alcohol problems are associated with gambling behaviors in emerging adults (Martens et al. 2009; Walker et al. 2010). In a longitudinal study, depression in adolescence predicted problem drinking (Pulkkinen and Pitkänen 1994) and gambling problems (Dussault et al. 2011; Martin et al. 2014; Wong et al. 2013) in emerging adulthood. Similar to depressive symptomatology, earlier antisocial behavior predicted later problem alcohol use (Lim and Lui 2016; Mason et al. 2010) and at-risk gambling in emerging adults (Winters et al. 2002).

The effects of alcohol, depression, and antisocial behavior on gambling may vary by gender. Alcohol use is a strong risk factor for gambling behaviors, especially for emerging adult men; risk of heavy alcohol use and alcohol problems and gambling disorder are greater for emerging adult men than for emerging adult women (Afifi et al. 2016; Caldeira et al. 2017; Edgren et al. 2016; Hodgins et al. 2016). Research also has revealed different gambling motivations by gender, suggesting specifically that men often gamble due to risk taking (e.g., antisocial behavior) and sensation seeking, whereas women frequently gamble to cope with emotional distress such as depressive symptomatology (Gupta et al. 2013).

Despite the fact that some studies have explored associations between alcohol use and gambling behaviors in emerging adults (Afifi et al. 2016; Caldeira et al. 2017), limited research has focused specifically on how factors such as depressive symptomatology, antisocial behavior, and alcohol use influence gambling in distinct ways based on gender and during the emerging adult developmental period. More evidence is needed to identify what underlying factors may influence the disparate findings regarding the relationships among alcohol use, gambling, and gender. It is also crucial to consider whether and how those factors can explain alcohol use as a risk factor for gambling. The present study addresses this gap by exploring gender differences in the prospective relationships among depression, antisocial behavior, alcohol use, and gambling behaviors in emerging adulthood.

Methods

Data Source and Sample

Study data came from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health). Add Health is a longitudinal (five wave) school-based survey of individual, family, school, neighborhood, and community influences on health, and health-related behaviors in the USA. Further information about the Add Health survey design, sampling, and administration procedures are described in detail elsewhere (Harris 2013; Harris et al. 2009). The current study included respondents ages 18–29 with valid longitudinal sampling weights for the data in Waves I (sociodemographics only, n = 20,745), III (n = 15,197), and IV (n = 15,701), with a final study sample of 8282 emerging adults. Secondary data analysis of the Add Health data was approved by the university Institutional Review Board where this research was conducted.

Measures

Gambling Behaviors

The Waves III and IV dataset include gambling behaviors. Respondents identified whether they had ever participated in different types of gambling (i.e., buying a lottery ticket, playing casino/video games, or playing any other games, such as cards, bingo, or bet on horse races or sporting events for money) at Wave III. The items on gambling participation at Wave III were combined and dichotomized (0 = no [those who never gambled], 1 = yes [those who ever participated in any type of gambling]). Gambling participation at Wave IV was assessed by whether respondents ever participated in any type of gambling with a single item (0 = no, 1 = yes). Among five items of gambling problems assessed at Wave III, the two items that measured financial and interpersonal problems related to gambling were used to create a measure comparable with the Wave IV measure. A composite dichotomous measure of gambling problems at Wave III was created, and a single item with two response options (0 = no, 1 = yes) was used to measure gambling problems at Wave IV. For the current study, gambling participation and problems at Wave III were used as independent variables, and those at Wave IV were the dependent variables.

Depression

The nine-item shortened version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff 1977) screened past-week depression at Wave III (0 = never or rarely, 1 = sometimes, 2 = a lot of the time, 3 = most of the time or all of the time). Previous research on this standardized self-report measure of the nine-item shortened version of the CES-D reveals adequate internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.79–0.83) and validity in adolescents and adults (Exner-Cortens et al. 2013). The internal consistency of the nine-item CES-D scale was .80 in the present study. For the main analyses, the proportionally adjusted cutoff scores of 10 for men and 11 for women were adopted to screen those at risk for depression on the basis of prior research (Needham and Austin 2010). The sum of the nine-item CES-D scale was dichotomized: 0 = no depression, 1 = experiencing any depression (i.e., responding 1, 2, or 3 to any of the nine items).

Antisocial Behavior

The 12-item delinquency scale (Guo et al. 2008), measuring past-year frequency of delinquency and violence (i.e., committing property offenses, person offenses, and drug offenses), assessed antisocial behavior at Wave III. Cronbach’s alpha for antisocial behavior (α = 0.73) was adequate in literature (Guo et al. 2008), and the internal consistency for antisocial behavior was 0.75 in this study. A composite dichotomous measure of antisocial behavior was created for this study (0 = never, 1 = at least once [i.e., those who reported one or more offenses]).

Alcohol Use Behaviors

Alcohol use behaviors at Wave III were assessed using respondents’ self-report of past-year alcohol use, binge drinking, heavy drinking, and alcohol-related problems. Past-year alcohol use was measured by the frequency of past-year alcohol use (0 = none, 1 = 1 or 2 days in the past 12 months, 2 = once a month or less [3–12 times in the past 12 months], 3 = 2 or 3 days a month, 4 = 1 or 2 days a week, 5 = 3–5 days a week, 6 = every day or almost every day). A count variable of incidents of Binge drinking (range 0–14) was recoded into a dichotomous variable based on gender, the frequency of past 2-week alcohol use of five or more drinks for men and four or more drinks for women on a single occasion. Heavy drinking was assessed by the frequency of drinking five or more drinks in a row (0 = none, 1 = 1 or 2 days in the past 12 months, 2 = once a month or less [3–12 times in the past 12 months], 3 = 2 or 3 days a month, 4 = 1 or 2 days a week, 5 = 3–5 days a week, 6 = every day or almost every day). For the present study, heavy drinkers were those who endorsed having five or more drinks in a row at least 5 days during the past year (0 = no heavy drinking, 1 = heavy drinking). Past-year alcohol-related problems were assessed with eight items including problems at school or work, interpersonal problems, sickness, sexual behaviors, physical fights, and drunkenness. The reliability of the alcohol-related problems scale ranged from 0.70 to 0.80 in literature (Fernández and Arango 2013; Wiersma and Fischer 2014) and was adequate in this sample (α = 77). The majority of research participants (94%) reported having no alcohol-related problems. On the basis of the distribution, a composite indicator of alcohol-related problem items was created (0 = no, 1 = yes).

Sociodemographics

Age, gender, and race/ethnicity were included as sociodemographic factors. The birth month and year of the respondents were measured at Waves III and IV in the Add Health survey. Age was calculated by subtracting the birth month and year from the interview month and year. Gender was dummy coded (0 = female, 1 = male). Race and ethnicity were recoded into five categories: White/Caucasian, non-Hispanic (reference group); Hispanic/Latino; Black/African-American, non-Hispanic; Asian/Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic; and other, non-Hispanic, and then each category was dummy coded for data analysis.

Data Analysis

Prior to the main analysis, descriptive analyses explored the characteristics of the sample, the variables of interest, and the distribution of the study variables using the SAS software version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc. 2011). Missing data for all study variables were less than 1%, and no outliers (|z| > 3.00) were detected. The values of variation inflation factor (VIF) ranged from 1 to 3, and all tolerance values were less than a value of 0.10, indicating no problematic multicollinearity (Kline 2011). The data were analyzed adjusting for sampling design to produce unbiased estimates and accurate standard errors of the estimates according to the complex sampling design of Add Health. Bivariate chi-square tests assessed the relationships between independent variables (i.e., sociodemographics, depression, antisocial behavior, alcohol use, gambling behaviors [Wave III]), and later gambling behaviors (Wave IV).

Multigroup models have the capacity to estimate differences of certain paths in a specified causal relationship across populations (Byrne 2012). As such, multigroup path analyses assessed the association between earlier depression, antisocial behavior, and alcohol use predicting later gambling behaviors across gender groups in emerging adulthood using Mplus Version 7.3 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2012). Multigroup path analyses also tested the invariance of structural parameters (e.g., regression paths) related to the observed variables.

We conducted a series of nested model tests based on existing standards (Barajas-Gonzalez and Brooks-Gunn 2014). First, the group-specific baseline models were tested separately within each group (i.e., women and men) to confirm that the original model fit the data when applied separately to each group. Second, the multigroup baseline model that allowed all parameters to vary across groups was estimated by simultaneously testing with the combined gender groups to provide information regarding the multigroup representation of the baseline model (Hu and Bentler 1999). Third, a model with all structural parameters constrained to be equal across gender groups was estimated to compare the overall model fit with the unconstrained multigroup baseline model. The model fit of the fully constrained model was worse than that of the multigroup baseline model; hence, we constrained nonsignificant parameters and allowed significantly different parameters to be freely estimated (i.e., allowed to vary between the groups) in order to determine which regression paths varied by gender on the basis of the literature, chi-square difference tests, and modification indices (MIs; Kline 2011).

Lastly, Wald chi-square tests were conducted on freed parameters to examine whether gender differences were present. Multiple model-fit tests evaluated the goodness of fit between the hypothesized model and the data using the following criteria: nonsignificant chi-square at a 0.05 threshold, the comparative fit index (CFI ≥ 0.95), the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI ≥ 0.95), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA ≤ 0.06) (Kline 2011; Hu and Bentler 1999).

Results

Sample Characteristics

Table 1 presents the sample characteristics. There were statistically significant relationships between gender and all main study variables (except for sociodemographics). Women were more likely than men to experience depression, whereas men were more likely than women to endorse antisocial behavior and to report alcohol use (i.e., past-year alcohol use, binge and heavy drinking, alcohol-related problems) and gambling participation and problems at both waves.

Results of Multiple Group Path Analysis

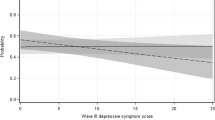

Multiple group path analysis was conducted to identify gender differences regarding the prospective relationships among depression, antisocial behavior, alcohol use, and gambling behaviors. There was an excellent fit of the model to data (χ2(110) = 122.20, p = 0.20; CFI = 0.999, TLI = 0.999, RMSEA = 0.01 [90% CI = 0.00–0.01, p = 1.00]). Depression was positively correlated with antisocial behavior (r = 0.18, p < 0.001), suggesting that a greater risk of experiencing depression was related to a higher risk of endorsing antisocial behavior for both women and men (Table 2 and Fig. 1). Earlier depression decreased the risk of later gambling participation (β = − 0.10, p = 0.03) in both gender groups.

Antisocial behavior was significantly associated with all alcohol use behaviors (i.e., past-year alcohol use, binge and heavy drinking, alcohol-related problems) in both gender groups, indicating a greater level of endorsing antisocial behavior was associated with a higher level of past-year alcohol use, binge and heavy drinking, and alcohol-related problems. Earlier heavy drinking was associated with an increased risk of later gambling participation (β = 0.19, p = 0.03), whereas earlier binge drinking was directly associated with a decreased risk of later gambling participation (β = − 0.18, p < 0.05).

Wald tests provided information on gender differences (Table 3). The Wald test results for parameter equality indicated significant gender differences between covariance of Wave III past-year alcohol use at and Wave III heavy drinking (χ2(1) = 15.44, p < 0.001), Wave III binge drinking and Wave IV gambling problems (χ2(1) = 10.61, p < 0.01), and Wave III alcohol-related problems and Wave III gambling participation (χ2(1) = 6.04, p < 0.05). Men (β = 0.84, p < 0.001) showed a stronger association between past-year alcohol use and heavy drinking than did women (β = 0.78, p < 0.001). Among emerging adult women, earlier binge drinking increased the risk of later gambling problems, but not among men.

Despite the significant Wald test results, all other parameters (except for the association between past-year alcohol use and heavy drinking) were nonsignificant in both gender groups. This indicates that gender differences regarding those associations are present. However, those coefficients are simultaneously or jointly equal to zero, and there is insufficient evidence to conclude that any specific coefficient is significant. Individual coefficients in each gender group may not explain enough by themselves to be statistically significant (Chou and Bentler 1990). However, including those parameters improved the model fit significantly.

Discussion

The results from the current study show some mixed findings. Consistent with prior literature (Lim and Lui 2016; Mason et al. 2010; Winters et al. 2002), we found that antisocial behavior is significantly associated with all alcohol use behaviors in both men and women, implying that when emerging adults engage in either antisocial behavior or alcohol use, they are at risk for both diagnoses. Alcohol use in emerging adulthood in this developmental period is considered to be relatively normative behavior, highlighting the primary functions of alcohol use, such as socialization (Schulenberg and Maggs 2002).

The finding that earlier heavy drinking is associated with later gambling participation is consistent with existing research (Martens et al. 2009; Walker et al. 2010). Heavy drinking in early emerging adulthood can be a warning sign for gambling participation in later emerging adulthood. However, this result differs somewhat from existing literature that found a stronger association between alcohol use and gambling in emerging adult men compared to emerging adult women (Afifi et al. 2016; Caldeira et al. 2017; Edgren et al. 2016; Hodgins et al. 2016). A potential explanation for this divergent finding may be that the link between alcohol use and gambling by gender may vary depending on other confounding factors.

The present study identifies that those who experienced earlier depression had a slightly lower likelihood of later gambling participation in both gender groups. Prior literature has suggested depression as a significant factor in problem gambling (Afifi et al. 2016; Dussault et al. 2011; Martin et al. 2014; Wong et al. 2013), but little is known about the negative association between earlier depression and later gambling participation. The time lag between Waves III and IV (i.e., 6 years) may have affected the negative relationship between earlier depression and later gambling participation in the current study. In emerging adulthood, some depression may be transient because of a variety of psychological, social, and environmental changes, and this may have affected the present findings. Depression may offset the risk of gambling when interacting with other confounding factors (e.g., antisocial behavior, impulsivity, friendship quality, socio-family risk). However, these possible explanations need to be further investigated with consideration of other confounding factors such as history of depression and personality traits (e.g., impulsivity, vulnerability to stress).

Gender Difference in the Behavioral Correlates of Gambling

The results from multigroup path analyses and the Wald tests reveal few gender differences in the relationships between past-year alcohol use and heavy drinking (Wave III), binge drinking (Wave III) and gambling problems (Wave IV), and alcohol-related problems and gambling participation (Wave III). Men show a stronger association between past-year alcohol use and heavy drinking than do women, consistent with prior research (Hodgins et al. 2016; Evans-Polce et al. 2015). The finding that earlier binge drinking is a risk factor for later gambling for women but not for men is inconsistent with earlier research that identified the positive association between binge drinking and gambling for both gender groups in college students (LaBrie et al. 2003). Although gender differences were also found in other parameters, these were not significant. The incidence and prevalence of the main study constructs do differ at the bivariate level. For instance, women have a higher level of depression but lower levels of other risk behaviors (e.g., antisocial behavior, alcohol use, alcohol-related problems, and gambling participation and problems) than men, consistent with literature (Afifi et al. 2016; Edgren et al. 2016; Hodgins et al. 2016).

The present study has some limitations that need to be considered. First, the nature of the secondary data made it difficult to obtain in-depth information regarding behaviors especially for gambling. Different patterns or results may be observed in research including severity and intensity of the same behaviors. Second, our analytical approach of estimating multiple group path models does not adjust for measurement error, which may decrease the accuracy in estimating relationships.

Despite its limitations, the current study has a number of strengths including a longitudinal design with a nationally representative sample of emerging adults and a data analytic approach that measures behavioral changes over time in emerging adults by gender. Our study contributes to the literature in understanding the developmental relations among depressive symptoms, antisocial behaviors, alcohol use, and gambling in emerging adulthood. The inclusion of both internalizing (e.g., depressive symptoms) and externalizing behaviors (e.g., antisocial behaviors) helped to identify how those behaviors play a role to predict gambling differently on the basis of gambling subtypes classified in existing research (Blaszczynski and Nower 2002; Gupta et al. 2013).

Conclusions

The results of this study suggest gender similarities in the associations between depression, antisocial behavior, and alcohol use predicting gambling behaviors among emerging adults, alongside gender differences in prevalence of these symptoms and behaviors. The links between antisocial behavior and alcohol use as well as heavy drinking and gambling support ongoing efforts in early prevention (including screening) and intervention for the co-occurrence of risk behavior in emerging adulthood. Especially, preventing problem gambling should be a priority because of its public health consequences. Interventions to curb some behaviors could be appropriate across gender (e.g. those displaying antisocial behavior and alcohol use at earlier ages), but treatment for men could be most effective if focusing on alcohol use.

References

Afifi, T. O., Nicholson, R., Martins, S. S., & Sareen, J. (2016). A longitudinal study of the temporal relation between problem gambling and mental and substance use disorders among young adults. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 61(2), 102–111.

Ahrnsbrak, R., Bose, J., Hedden, S. L., Lipari, R. N., & Park-Lee, E. (2017). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Barajas-Gonzalez, R. G., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2014). Income, neighborhood stressors, and harsh parenting: test of moderation by ethnicity, age, and gender. Journal of Family Psychology, 28(6), 855–866.

Blaszczynski, A., & Nower, L. (2002). A pathways model of problem and pathological gambling. Addiction, 97(5), 487–499.

Blinn-Pike, L., Worthy, S. L., & Jonkman, J. N. (2010). Adolescent gambling: a review of an emerging field of research. Journal of Adolescent Health, 47(3), 223–236.

Byrne, B. M. (2012). Structural equation modeling with Mplus: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. New York, NY: Routledge.

Caldeira, K. M., Arria, A. M., O’Grady, K. E., Vincent, K. B., Robertson, C., & Welsh, C. J. (2017). Risk factors for gambling and substance use among recent college students. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 179, 280–290.

Chou, C. P., & Bentler, P. M. (1990). Model modification in covariance structure modeling: a comparison among likelihood ratio, Lagrange multiplier, and Wald tests. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 25(1), 115–136.

Dussault, F., Brendgen, M., Vitaro, F., Wanner, B., & Tremblay, R. E. (2011). Longitudinal links between impulsivity, gambling problems and depressive symptoms: a transactional model from adolescence to early adulthood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52(2), 130–138.

Edgren, R., Castrén, S., Jokela, M., & Salonen, A. H. (2016). At-risk and problem gambling among Finnish youth: the examination of risky alcohol consumption, tobacco smoking, mental health and loneliness as gender-specific correlates. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 33(1), 61–80.

Evans-Polce, R. J., Vasilenko, S. A., & Lanza, S. T. (2015). Changes in gender and racial/ethnic disparities in rates of cigarette use, regular heavy episodic drinking, and marijuana use: ages 14 to 32. Addictive Behaviors, 41, 218–222.

Exner-Cortens, D., Eckenrode, J., & Rothman, E. (2013). Longitudinal associations between teen dating violence victimization and adverse health outcomes. Pediatrics, 131(1), 71–78.

Fernández, A. S., & Arango, N. M. (2013). Dating violence in relation to problem drinking and risky sexual behaviors. International E-Journal of Criminal Sciences, 7, 1–26.

Guo, G., Roettger, M. E., & Cai, T. (2008). The integration of genetic propensities into social-control models of delinquency and violence among male youths. American Sociological Review, 73(4), 543–568.

Gupta, R., Nower, L., Derevensky, J. L., Blaszczynski, A., Faregh, N., & Temcheff, C. (2013). Problem gambling in adolescents: an examination of the pathways model. Journal of Gambling Studies, 29(3), 575–588.

Harris, K. M. (2013). The add health study: Design and accomplishments. Chapel Hill, NC: Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Harris, K. M., Halpern, C. T., Whitsel, E., Hussey, J., Tabor, J., Entzel, P., & Udry, J. R. (2009). The national longitudinal study of adolescent to adult health: research design [WWW document]. http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design. Accessed 16 February 2016.

Hodgins, D. C., von Ranson, K. M., & Montpetit, C. R. (2016). Problem drinking, gambling and eating among undergraduate university students. What are the links? International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 14(2), 181–199.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55.

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford press.

LaBrie, R. A., Shaffer, H. J., LaPlante, D. A., & Wechsler, H. (2003). Correlates of college student gambling in the United States. Journal of American College Health, 52(2), 53–62.

Lim, J. Y., & Lui, C. K. (2016). Longitudinal associations between substance use and violence in adolescence through adulthood. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 16(1–2), 72–92.

Martens, M. P., Rocha, T. L., Cimini, M. D., Diaz-Myers, A., Rivero, E. M., & Wulfert, E. (2009). The co-occurrence of alcohol use and gambling activities in first-year college students. Journal of American College Health, 57(6), 597–602.

Martin, R. J., Usdan, S., Cremeens, J., & Vail-Smith, K. (2014). Disordered gambling and co-morbidity of psychiatric disorders among college students: An examination of problem drinking, anxiety and depression. Journal of Gambling Studies, 30(2), 321–333.

Mason, W. A., Hitch, J. E., Kosterman, R., McCarty, C. A., Herrenkohl, T. I., & David Hawkins, J. (2010). Growth in adolescent delinquency and alcohol use in relation to young adult crime, alcohol use disorders, and risky sex: a comparison of youth from low-versus middle-income backgrounds. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51(12), 1377–1385.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2012). Mplus user's guide (7th ed.). Log Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Needham, B. L., & Austin, E. L. (2010). Sexual orientation, parental support, and health during the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(10), 1189–1198.

Pulkkinen, L., & Pitkänen, T. (1994). A prospective study of the precursors to problem drinking in young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 55(5), 578–587.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401.

SAS Institute Inc. (2011). Base SAS® 9.3 Procedures Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.

Schulenberg, J. E., & Maggs, J. L. (2002). A developmental perspective on alcohol use and heavy drinking during adolescence and the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement, 14, 54–70.

Slutske, W. S., Jackson, K. M., & Sher, K. J. (2003). The natural history of problem gambling from age 18 to 29. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112(2), 263–274.

Sussman, S., & Arnett, J. J. (2014). Emerging adulthood: developmental period facilitative of the addictions. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 37(2), 147–155.

Walker, D. M., Clark, C., & Folk, J. L. (2010). The relationship between gambling behavior and binge drinking, hard drug use, and paying for sex. UNLV Gaming Research & Review Journal, 14(1), 15–26.

Wiersma, J. D., & Fischer, J. L. (2014). Young adult drinking partnerships: alcohol-related consequences and relationship problems six years later. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 75(4), 704–712.

Winters, K. C., Stinchfield, R. D., Botzet, A., & Anderson, N. (2002). A prospective study of youth gambling behaviors. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 16(1), 3–9.

Wong, G., Zane, N., Saw, A., & Chan, A. K. K. (2013). Examining gender differences for gambling engagement and gambling problems among emerging adults. Journal of Gambling Studies, 29(2), 171–189.

Acknowledgments

This research uses data from Add Health, a program project directed by Kathleen Mullan Harris and designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and funded by grant P01-HD31921 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations. Special acknowledgment is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Information on how to obtain the Add Health data files is available on the Add Health website (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth). No direct support was received from grant P01-HD31921 for this analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was supported by the competitive dissertation grant from University of Maryland School of Social Work.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Add Health participants provided written informed consent for participation in all aspects of Add Health in accordance with the University of North Carolina School of Public Health Institutional Review Board guidelines that are based on the Code of Federal Regulations on the Protection of Human Subjects 45CFR46: http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/humansubjects/guidance/45cfr46.html.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jun, HJ., Sacco, P., Bright, C. et al. Gender Differences in the Relationship Between Depression, Antisocial Behavior, Alcohol Use, and Gambling during Emerging Adulthood. Int J Ment Health Addiction 17, 1328–1339 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-0048-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-0048-9