Abstract

Research into Internet gaming disorder (IGD) literature largely uses cross-sectional designs and seldom examines gaming context-related factors. Therefore, the present study combined a cross-sectional and longitudinal design to examine depression and the gamer-avatar relationship (GAR) as risk factors in the development of IGD among emerging adults. IGD behaviors of 125 gamers (64 online gamers, Mage = 23.3 years, SD = 3.4; 61 offline gamers, Mage = 23.0 years, SD = 3.4) were assessed using the nine-item Internet Gaming Disorder Scale Short Form (IGDS-SF9; Pontes and Griffiths Revista Argentina de Ciencias del Comportamiento, 7, 102–118, 2015a; Computers in Human Behavior, 45, 137–143, 2015b). The Self-Presence Scale (Ratan and Dawson Communication Research, 2015) and the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck et al. 1996) were also used to assess gamers’ levels of GAR and depressive symptoms, respectively. Regression and moderation analyses revealed that depression and the GAR act as individual risk factors in the development of IGD over time. Furthermore, the GAR exacerbates the IGD risk effect of depression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The expansion of online gaming has led to excessive and potentially problematic gaming among a small minority of individuals (Pontes and Griffiths 2014). The first commercial video games made their debut in the USA in the 1970s, and by the early 1980s, reports of video gaming addiction began to appear in academic literature (Kowert and Quandt 2015). In the 2000s, there was a substantial growth in video game playing, video game addiction, and associated research (Griffiths 2015). As the medium has developed, it has enabled an online environment where gamers can gather virtually and create global online communities (Griffiths 2015). Consequently, there has been a significant growth over the last decade of research examining both online video gaming and video game addiction (Griffiths et al. 2016b; Petry et al. 2014a, b).

Various terms have been employed to define excessive online video gameplay such as “problem video game playing,” “video game addiction,” “Internet gaming addiction,” “pathological video game use,” “problem video game play,” “online gaming addiction,” “video game dependency,” “pathological gaming,” and “problematic online gaming” (Pontes and Griffiths 2014). The wide variety of names, definitions, and diagnostic instruments applied to problematic video gaming has resulted in inconsistencies among researchers considering the prevalence of the behavior (King et al. 2013b; Kuss and Griffiths 2012a; Petry et al. 2014a, b). In May 2013, the American Psychiatric Association (APA 2013) introduced the classification of Internet gaming disorder (IGD, i.e., the problematic use of online video games) as a condition worthy of further study in the latest (fifth) edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). Literature reviews have identified a diagnostic overlap between studies that had previously investigated problematic video gameplay and more recent ones examining IGD (Petry et al. 2015; Pontes and Griffiths 2014), indicating that the many names used to describe problematic online video gaming behaviors have been used interchangeably to describe IGD, as the concept did not previously exist (Kuss and Griffiths 2012a).

IGD is characterized by the persistent and ongoing use of the Internet to engage in online video games, and which leads to significant impairment or distress (APA 2013). The nine core criteria of IGD closely resemble the conceptualization of addictive behaviors (e.g., substance use, gambling, etc.) and include impaired control and harmful consequences as a consequence of engaging in the behavior (APA 2013; King et al. 2013a, b). IGD-related behaviors can result in a wide range of negative psychosocial repercussions including sacrificing work, education, socializing, and hobbies (Griffiths et al. 2004; Rehbein et al. 2010; Yee 2006a), increased stress (Batthyány et al. 2009), lower psychosocial wellbeing and loneliness (Lemmens et al. 2011), poorer social skills (Griffiths 2010), decreased academic achievement (Jeong and Kim 2011; Rehbein et al. 2010), increased inattention (Faiola et al. 2013), maladaptive coping (Batthyány et al. 2009; Hussain and Griffiths 2009a, b), and auditory and visual hallucinations (Ortiz de Gortari and Griffiths 2013, 2014, 2016). Given that IGD presents a significant potential public health risk (APA 2013), understanding its precursors may provide information that can be used for more effective prevention and intervention policies (Kuss and Griffiths 2012b).

Risk and Resilience Framework and Internet Gaming Disorder

To address this aim, and in line with previous studies on addictive behaviors, the present research adopts the risk and resilience framework (RRF) to investigate IGD behaviors (Hendriks 1990; Ko 2014; Stanley 2015). According to the RRF, the intensity of pathological behaviors constantly changes upon a continuum (from minimum to maximum behaviors; Stanley 2015). Furthermore, addictive behaviors and their severity are defined not only by the characteristics of the individual (i.e., personal attributes), but their contextual factors (i.e., family and peer influences), and the interplay between the two over a period of time (Griffiths 2005). These effects can either buffer (i.e., resilience factors) or increase the rate of a pathological behavior (i.e., risk factors; Masten 2001). Thus, the present study conceptualizes IGD behaviors dimensionally and considers risk and protective factors referring to age-related changes, effects located within the individuals, their offline context, and their online context (Kuss and Griffiths 2012a; Masten 2014). To investigate the latter, the present study has enriched the RRF with key elements from the IGD literature referring to the gaming experience and concurrently focuses on those in emerging adulthood as an underresearched developmental period (Douglas et al. 2008) regarding IGD.

Addiction in Emerging Adulthood

Despite the existence of multiple risks that may facilitate addiction during emerging adulthood (Arnett 2005; Sussman and Arnett 2014), IGD research has disproportionally focused on adolescence (Kuss and Griffiths 2012a; Festl et al. 2013). Arnett (2000) suggests that emerging adulthood is a distinct transitional developmental period in which identity forms, mature interpersonal relationships initiate, and new adult-type roles emerge. These multiple transitions may often induce discomfort that can potentially precipitate addictive behaviors. More specifically, addictive patterns (that an individual might have experimented with during adolescence) may consolidate as maladaptive emotion regulation strategies during emergent adulthood (Ackerman 2009; Khantzian 1997; Ream et al. 2013). In line with this, playing video games have been shown to help gamers regulate their negative emotions in a similar way to substances for substance abusers (Ream et al. 2013). This emotional self-regulation pattern may be strengthened during emerging adulthood, as dependent supervision is no longer enforced, yet adult-type roles are not fully developed (Arnett 2000; Ream et al. 2013; Sussman and Arnett 2014). However, “self-medicating the pain of growing up” (through addictions including IGD behaviors) may compromise concurrent and future adaptation (Baumrind and Moselle 1985; Pandina et al. 1990). Consequently, the developmental period of emerging adulthood is of specific interest when investigating online gaming. This is further reinforced by both the prevalence of online gaming, as well as IGD behaviors being elevated during this developmental time (APA 2013; Yee 2006b).

Massively Multiplayer Online Games

Online games appeal to a diverse population of players due to the variety of available genres, which may include racing, fighting, shooting, and role-playing games, with different genres assuming different sets of skills (Kuss 2013). The present research focuses on massively multiplayer online (MMO) games, particularly because they have been repeatedly linked to an increase in IGD behavior (Billieux et al. 2015; Kuss 2013; Stavropoulos et al. 2016b, Young 2009). MMOs allow a gamer to socially interact with other gamers in a shared virtual space (Kim and Kim 2010). Kuss and Griffiths (2012b) identified a plethora of gaming sub-genres within the MMO game genre itself. These include (but are not limited to) casual browser games (CBGs), first person shooter (FPS) games, massively online battle arena (MOBA) games (Meng et al. 2015), simulation games (SGs), and massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs). MMORPGs in particular comprise massive virtual environments in which a gamer can explore and consistently interact within the virtual world (Badrinarayanan et al. 2014) and are typically played by hundreds of thousands of gamers simultaneously (Ducheneaut et al. 2007).

MMO games may be endless due to the regularly updated content, widespread goals, and personal achievements (Stetina et al. 2011). Consequently, research has shown that MMO gamers play more often (Ng and Wiemer-Hastings 2005) and longer than any other online video game sub-genre (Stetina et al. 2011). Accordingly, they present a higher risk for the development of excessive gaming (Ko 2014; Stavropoulos et al. 2017). Studies have suggested that this is due to a combination of several factors that appear to make MMO games attractive and absorbing including character development (particularly in MMORPGs), in game progression, and in game socialization (Stetina et al. 2011; Wei et al. 2012). Furthermore, it appears that individuals within emerging adulthood, who specifically play MMO games, are at higher risk of developing IGD behaviors (Ko 2014; Scott and Porter-Armstrong 2013; Stavropoulos et al. 2016b; Stetina et al. 2011). Therefore, the present research investigates IGD behaviors of emergent adults, and more specifically MMO gamers in relation to depression and gamer-avatar relationship (GAR), that constitute two critical individual IGD risk factors.

Depression and Internet Gaming Disorder

The associations between depression and addictive behaviors, technological addictions, and IGD have been consistently supported (Griffiths et al. 2016a; Stetina et al. 2011; Stone et al. 2012; Swendsen and Merikangas 2000; Volkow 2004; Yen et al. 2007). Addictions have been often conceptualized as attempts to self-regulate and moderate negative emotions through external means. This may be effective for a time but can ultimately become excessive (Griffiths 2005; Khantzian 1997). Furthermore, studies have postulated that online addictive behaviors (including IGD) entail several potential emotion regulation functions via the reinforcing feelings of control, securing online social acknowledgement, and compensating for real-life disadvantages (Yen et al. 2007). Additionally, IGD behaviors may be preferred as they are often perceived as less harmful than other forms of addictions (Yen et al. 2007). Despite these theoretical notions, there have been few studies (particularly longitudinal) investigating the associations between depression and IGD within emerging adulthood (Galambos et al. 2006; King and Delfabbro 2014; Pontes and Griffiths 2015a). This gap appears important (besides the IGD significance of emerging adulthood) because excessive online behaviors have been typically described as secondary conditions resulting from various primary disorders such as depression (Dong et al. 2011; Ko et al. 2012). Within this theoretical frame, playing video games excessively may serve as a strategy for relieving preexisting depression psychopathology, which could in turn reinforce further symptomatology, although more research is needed (Ko et al. 2012). The present study will seek to expand the empirical understanding of the association between depression and IGD by combining a cross-sectional and prospective examination of depression symptoms as a predictor of IGD. This is significant given that excessive online behavior appears to decline among older and more experienced users, possibly due to maturation and saturation effects (Vollmer et al. 2014). The present study addresses this by considering the relationship between gamers and their avatar (i.e., virtual persona).

The Gamer-Avatar Relationship

An avatar functions as a game representation of the player’s identity that may often merge with their real-life self (Pringle 2015). The avatar is one of the defining features that affect a gamer’s psychological experience while playing MMO games or MMORPGs (Klimmt et al. 2009). The more a gamer uses their avatars, the more the avatars gain experience, knowledge, skills, achievements, and resources, and thus accumulating in-game value (Bessiere et al. 2007; Carter et al. 2012). Furthermore, gamers use their avatars to form groups and intergroup collaborations to progress in the game, which gives rise to the development of robust virtual communities (Badrinarayanan et al. 2014; Bessiere et al. 2007; Ducheneaut et al. 2007). Consequently, the gamer’s interrelation with their avatar frequently develops into a psychological attachment which gradually strengthens (especially in MMORPGs; Bessiere et al. 2007; Wolfendale 2007).

This type of attachment generates a sense that a gamer’s body, physiological states, emotional states, perceived traits, and identity exist within the virtual environment (Biocca 1997) and has been defined by Ratan (2013) as “self-presence.” Research suggests that those who experience a high level of self-presence incline to imbue their avatar with intrinsic qualities and/or physical characteristics that they desire to possess. This occurs more frequently when gamers create idealized identities of their actual self, attempting to reconcile self-discrepancies in real life (Bessiere et al. 2007). This function appears particularly important because individuals’ psychological well-being is linked to the difference between their actual self and ideal self (Higgins et al. 1987). Given that larger actual-ideal self-discrepancies are associated with higher levels of depression, it could be assumed that a gamer may create an idealized self which is projected onto the avatar to address their depressive feelings (Badrinarayanan et al. 2014; Bessiere et al. 2007; Caplan et al. 2009; Messinger et al. 2008; Ko 2014; Stavropoulos et al. 2016b). This type of process can frequently be found in MMOs and have been related to longer times spent online (Ng and Wiemer-Hastings 2005). Given (to the best of the authors’ knowledge) the lack of relevant studies, it is important to investigate the way in which the GAR could exacerbate the risk effect of depression on IGD behaviors.

The Present Study and Hypotheses

The present study adopted an RRF theoretical perspective that dimensionally conceptualized IGD behaviors to explore the gamers’ levels of depression and identification with their avatars (self-presence), as well as their interplay, as potential IGD risk factors. To address these aims, the present study combined a cross-sectional and a longitudinal methods design (three measurements over a period of 3 months, 1 month apart each). More specifically, it examined a sample of Australian emergent adults (18–29 years), MMO and MMORPG players, collected online and face-to-face.

Studies suggest that higher levels of depression are associated with different forms of addiction (Griffiths et al. 2016a, b; Hendriks 1990; Swendsen and Merikangas 2000). Furthermore, preliminary cross-sectional findings indicate a significant association between depression and IGD risk in emerging adults (Galambos et al. 2006; Stetina et al. 2011; Wei et al. 2012). Empirical evidence suggests that MMO players create an avatar in which they often imbue part of their identity and idealized identity (Bessiere et al. 2007)—a behavior more frequent with gamers above the age of 18 years (i.e., emerging adults; Ducheneaut et al. 2009). This identity investment suggests that gamers may experience high levels of self-presence, causing their gameplay to increase and to aid in developing IGD behaviors (Ko 2014; Ng and Wiemer-Hastings 2005; Stavropoulos et al. 2017). Gamers with higher levels of depression may experience a greater discrepancy between their ideal and actual selves (Bessiere et al. 2007; Messinger et al. 2008). This may prompt them to project their idealized selves onto their avatars as a way to regulate related depressive emotions (Bessiere et al. 2007). Consequently, a greater attachment to the avatar is formed (Ducheneaut et al. 2009) that encourages longer gameplay sessions and IGD behaviors (Badrinarayanan et al. 2014; Ko 2014; Ng and Wiemer-Hastings 2005; Stavropoulos et al. 2016b). Based on the findings outlined in this section, three hypotheses were formulated and investigated. More specifically it was hypothesized that (i) gamers with higher depression scores would be at a greater risk of developing IGD behaviors, (ii) gamers who experience higher GAR would be at greater risk of developing IGD behaviors, and (iii) higher GAR experience among gamers would exacerbate the effect of depression on IGD behaviors.

Method

Participants

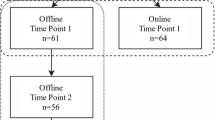

The sample comprised 125 emerging adults aged 18–29 years oldFootnote 1 (Arnett et al. 2014) who played MMOs and/or MMORPGs. The 125 gamers comprised 64 online cross-sectional respondents (Mage = 23.34, SD = 3.39, minage = 18, maxage = 29, males = 49, 77.6%) and 61 offline, face-to-face, longitudinal respondents (Mage = 23.02, SD = 3.43, minage = 18, maxage = 29, males = 47, 75.4%). Online and face-to-face data (i.e., time point 1) were combined to investigate cross-sectional questions.Footnote 2 Face-to-face longitudinal dataFootnote 3 (i.e., time point 1 [T1], time point 2 [T2], and time point 3 [T3]) were analyzed separately to address hypotheses related to changes over time. A complete summary of the sociodemographic characteristic can be found in Table 1. The estimated maximum sampling errors with a size of 125 (cross-sectional sample) and a size of 61 (longitudinal sample) are 8.77 and 12.55%, respectively (Z = 1.96, confidence level 95%).

The face-to-face longitudinal sample were assessed three times over a period of three months (i.e., between June 1, 2016, and September 5, 2016) using a re-identifiable code (i.e., Fitbit email account). The assessment frequency for each participant varied within a range of 1–3 (Maverage = 2.57). More specifically, 61 participants completed T1, 56 participants completed T2 (91.80% retention vs. 8.20% attrition between T1 and T2), and 43 participants completed T3 (70.49% retention vs. 29.51% attrition between T1 and T3) (Fig. 1).

Measures

A battery of scales (see below) and questions concerning demographic information (i.e., gender, age, occupation, education level, living status, relationship status, preferred game, and Internet use questions) were applied.1

Internet Gaming Disorder Scale–Short Form 9 (IGDS-SF9)

IGD behaviors were assessed using the IGDS-SF9 (Pontes and Griffiths 2015b). It includes nine items, based on the nine core IGD criteria of the DSM-5 (APA 2013), and assesses the severity of IGD behaviors (e.g., “Do you systematically fail when trying to control or cease your gaming activity?”). The items are addressed on a 5-point Likert scale: 1 (“Never”), 2 (“Rarely”), 3 (“Sometimes”), 4 (“Often”), and 5 (“Very Often”). To calculate the final IGD score, items’ points are accumulated ranging from 9 to 45 with higher scores being indicative of higher severity of IGD behaviors. Internal reliability in the current study was high, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.92.

Beck Depression Inventory–Second Edition (BDI-II)

To assess depressive behaviors, the Beck Depression Inventory–Second Edition (BDI-II; Beck et al. 1996) was used. The BDI-II includes 21 self-report items on an inventory that assesses the severity of depressive symptoms within the last 2 weeks (Beck et al. 1996). Items are rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (e.g., “I do not feel sad”) to 3 (e.g., “I am so sad and unhappy that I cannot stand it). To calculate the final BDI-II score, the points are added ranging from 0 to 63 with higher scores indicating higher symptoms of depression. The instrument had a high internal reliability rate in the present study with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.90.

Self-Presence Questionnaire (SPQ)

To assess GAR (i.e., the level of identification by gamers with their avatar), the SPQ was used (Ratan and Dawson 2015). The SPQ is a 13-item self-report questionnaire that dimensionally assesses three distinct areas: (i) Proto Self-Presence (PSP-5 items) describes the extent to which players experience their avatar as the extension of their real body (e.g., “When playing the game, how much do you feel like your avatar is an extension of your body within the game?”); (ii) Core Self-Presence (CSP-5 items) describes the extent to which game-related interactions cause real emotional responses to the user (“When sad events happen to your avatar, do you also feel sad?”); and (iii) Extended Self-Presence (ESP-3 items) describes the extent to which the avatar resembles the personal identity of the gamer (“To what extent does your avatar’s name represent some aspect of your personal identity?”). Items are addressed on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “Not at all” to 5 = “Absolutely”) and the points are added to produce the overall SPQ (GAR) score with higher scores indicating a higher GAR, respectively. The SPQ has shown to be an internally reliable measure with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.91 in the present study.

Procedure

This project was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Federation University Australia. Participants were recruited in the general community using traditional (i.e., information flyers) and electronic (i.e., email, social media) advertising methods.Footnote 4 The face-to-face, longitudinal component of the study was conducted over a 3-month period, with the three time-point assessments completed between June 1, 2016, and September 5, 2016. The process of data collection was identical between the three time points, and participants’ data were matched through the use of a re-identifiable code. A specially trained research team of five undergraduate students and two postgraduate students collected the face-to-face data. Mutually agreed data collection appointments were organized with each of the participants (25–35 min each).

The online data were collected between June 1, 2016, and July 1, 2016. Based on the ethical approval received, eligible individuals interested in participating and unable or unwilling to attend face-to-face testing sessions were invited to register with the study via a Survey Monkey link available on MMO websites and forums (i.e., http://www.ausmmo.com.au). The link directed them to the plain language information statement. Individuals who chose to participate online had to digitally provide informed consent by clicking a button.

Statistical Analysis

To assess the association between depression levels and IGD behaviors (H 1), two hierarchical linear regression models were conducted on the cross-sectional and the longitudinal data, respectively. In the cross-sectional analysis, IGD scores were used as the outcome variable and depression scores were used as the predictor. In the longitudinal analysis, the same hierarchical linear regression model was calculated with the differences of (i) IGD behaviors assessed at T3 being used as the outcome variable and (ii) depression levels assessed at T1 being used as the IGD predictor variable (face-to-face data only). To assess the potential risk effect of GAR on the IGD behaviors (H 2) cross-sectionally and longitudinally, the same two models (see H 1) were conducted with depression being replaced by SPQ-GAR scores as the IGD predictor.

To assess the potentially exacerbating (risk) effect of GAR on the IGD risk of gamers, who present with higher depressive symptoms (H 3), a moderation analysis was conducted using only the longitudinal data through the Process macro (Hayes 2013) on SPSS 21. The use of the longitudinal data only was based on recommendations supporting that causal associations should be best addressed longitudinally (Winer et al. 2016). More specifically, depression at T1 was used as the independent variable, GAR at T2 was used as the moderator, and IGD behaviors at T3 were used as the outcome variable. Finally, the Johnson-Neyman (J-N) technique was applied to derive regions of significance (i.e., points of transition) of the moderation effect of GAR on the association between depression and IGD behaviors (Preacher et al. 2007).

Results

Prior to investigating the hypotheses, descriptive statistics and intercorrelations between the examined variables were calculated (see Appendix and Tables 2 and 3). To cross-sectionally assess the first hypothesis (i.e., gamers with higher depression scores would be at a greater risk of developing IGD behaviors), IGD scores were inserted as the dependent variable, and depression scores were used as the independent variable in a linear regression analysis model, and bootstrapping was applied on the minimum recommended level of 1000 (Berkovits et al. 2000). Results demonstrated that the slope of the regression line was statistically significant (F (1, 120) = 54.92, p = < .001). More specifically, 31.4% of the variance of IGD scores was explained by depression scores (R 2 = .31). For each point of increase in depression scores, IGD scores increased by 0.43 (b = 0.43, SE(b) = 0.06, β = 0.56 , t = 7.41, p < .001).

To confirm the direction of causality and assess the association, IGD scores assessed at T3 were inserted as the dependent variable and depression scores at T1 were inserted as the independent variable in a second linear regression model. As above, bootstrapping on the minimum recommended level of 1000 was applied. Results demonstrated a significant regression equation (F (1, 56) = 4.86, p = .03) with 8% of the variance of IGD scores at T3 being explained by depression scores at T1 (R 2 = 0.08). Accordingly, for each point of increase of depression scores at T1, IGD scores at T3 increased by 0.21 (b = 0.21, SE(b) = 0.09, β = 0.28, t = 2.20, p < .05).

To cross-sectionally assess the second hypotheses (i.e., gamers who experience higher GAR would be at greater risk of developing IGD behaviors), IGD behaviors were inserted as the dependent variable, and GAR scores were used as the independent variable in a linear regression model, and bootstrapping was applied on the minimum recommended level of 1000. The slope of the regression line was statistically significant (F (1, 120) = 38.20, p = < .001) with 24.2% of the variance of IGD scores being explained by the GAR scores (R 2 = 0.24). For each point of increase of GAR scores, IGD scores increased by 0.37 (b = 0.36, SE(b) = 0.06, β = 0.49, t = 6.18, p < .001).

To investigate the direction of causality and assess whether this association held over time, IGD behaviors assessed at T3 were applied as the dependent variable, and GAR scores at T1 were applied as the independent variable. Bootstrapping on the minimum recommended level of 1000 was applied. A significant regression equation was demonstrated (F (1, 56) = 19.71, p = < .001) with 26% of the variance of IGD scores at T3 were explained by GAR scores at T1 (R 2 = 0.42). Accordingly, for each point of increase of GAR scores at T1, IGD scores at T3 increased by 0.27 (b = 0.27, SE(b) = 0.06, β = 0.51 , t = 4.44, p < .001).

A moderation analysis was conducted to address the third hypothesis (i.e., higher GAR experience among gamers would exacerbate the effect of depression on IGD behaviors), adopting the methodology recommended by Hayes (2013). The longitudinal data were chosen following literature recommendations that causative associations are better supported by longitudinal data (Winer et al. 2016). More specifically, the model aimed to estimate the effect of depression scores at T1 on IGD scores at T3 and how much, if any, the effect depends on GAR scores at T2, as assessed on the SPQ. Thus, depression scores (BDI-II) were the focal predictor (F), and GAR scores (SPQ) were the proposed moderator (M). Bootstrapping on the minimum recommended level of 1000 was applied. The model estimated was as follows:

\( {\displaystyle \begin{array}{l}\mathrm{IGD}\kern0.5em \mathrm{Scores}=a+b1\kern0.5em Depression\kern0.5em Scores(T1)+b2\kern0.5em GAR\kern0.5em Scores(T2)+b3\\ {}\left[ Depression\kern0.5em Scores(T1) xGAR\kern0.5em Scores\kern0.5em (T2)\right];\end{array}} \)

The overall model was significant (F (3, 54) = 16.45, p = < .001). More specifically, 47.76% of the variance of IGD scores at T3 were explained by depression scores at T1, GAR scores at T2, and their interaction (R 2 = 0.48). Furthermore, depression at T1 and the GAR at T2 interacted in regards to the severity of IGD scores at T3 [b3 = 0.02, t(54) = 2.35, p = .02]. The coefficient for the interaction indicated that as the GAR at T2 increases by one unit, the coefficient for the depression scores at T1 on IGD scores at T3 increases by 0.02. A visual representation of this exacerbating effect is shown in Fig. 2.

Lastly, the J-N technique was applied to derive regions of significance (i.e., points of transition) and to more clearly describe how the association of depression scores on IGD scores varied as a function of GAR scores (Preacher et al. 2007). Findings demonstrated that when the score of the GAR is 12.09 or higher, the risk affect for depression scores on IGD scores were significant with a trend to increase.

Discussion

The present study integrated the RRF with key concepts from the gaming literature to examine cross-sectional and longitudinal variations (three points across a period of 3 months, 1 month apart each) in IGD behaviors in an Australian sample of MMO gamers, assessed online and face-to-face. More specifically, it examined whether (i) higher depressive behaviors and stronger GAR functioned as IGD risk factors and (ii) higher GAR exacerbated the IGD risk of more depressed players. Linear regression and moderation analyses demonstrated that higher depressive behaviors and stronger GAR were associated with increased IGD behaviors both cross-sectionally and longitudinally. Furthermore, depressed adolescents were significantly more susceptible to IGD over time, when they experienced stronger GAR. These findings demonstrate the need to consider the interplay between individual and gaming-related factors when examining IGD behaviors and planning appropriate prevention and intervention strategies in helping individuals overcoming IGD.

Depression and Internet Gaming Disorder

When considering offline psychological factors, findings suggest that higher levels of depression associate with higher IGD behaviors, in line with previous studies (Griffiths et al. 2016a, b; Stetina et al. 2011; Yen et al. 2007). Depression has consistently been associated with an increased risk for developing a range of addictive behaviors including substance and alcohol abuse (Swendsen and Merikangas 2000; Volkow 2004). Similar results have been replicated in studies emphasizing the developmental period of emerging adulthood and IGD behaviors, especially among MMO players (Arnett 2005; Galambos et al. 2006; Scott and Porter-Armstrong 2013; Stetina et al. 2011; Stone et al. 2012; Sussman and Arnett 2014; Wei et al. 2012; Yen et al. 2007; Young and Rodgers 1998). The findings of the present study add to this growing body of literature.

The contribution of depression as an IGD risk factor may be explained on the basis of addictions often functioning as maladaptive emotional regulation strategies (Stavropoulos et al. 2016a). For example, adolescents have been shown to seek out online video gaming to experience positive feelings (e.g., being in control and being respected by others), which prompt the increase of their playing time as a way to address depression experienced offline (Yen et al. 2007). This has also been found in other behavioral addictions such as gambling where the activity is used as a means to escape and modify negative mood states (Griffiths 2011; Wood and Griffiths 2007). The findings also support the “compensatory Internet use” hypothesis, which assumes that excessive online users/gamers often aim to counterbalance for real-life disadvantages through absconding online (Kardefelt-Winther 2014). Cross-sectional studies further reinforce this interpretation for adult and emerging adult samples in particular (Stetina et al. 2011; Wei et al. 2012). It is indeed possible that IGD behaviors that initially provide an immediate positive feeling might later magnify real-life dysfunctions (i.e., neglect of everyday obligations) that could both precipitate and perpetuate depressive feelings, thus generating a vicious cycle (Stavropoulos et al. 2016a). In this context, the findings of the present study emphasize the need to consider (and potentially to aim to moderate/address) depression related developmental trajectories during emerging adulthood and their interplay with IGD risk behaviors.

Gamer-Avatar Relationship and Internet Gaming Disorder

With regards to gaming-related factors, results in the present study support the notion that stronger GAR is associated with increased IGD risk both cross-sectionally and longitudinally (King and Delfabbro 2016; Yee 2006b, 2014). This concurs with previous cross-sectional studies referring to emerging adults and MMO players (Blinka 2008; Smahel et al. 2008; Yee 2006a), as well as findings showing that longer playing time is associated with higher GAR (Muller et al. 2015; Ng and Wiemer-Hastings 2005). The findings could be due to the higher levels of identification and immersion between the gamer and the avatar involved in stronger GAR, and the increased gameplay that results from such a relationship (Badrinarayanan et al. 2014; Blinka 2008; Yee 2006a, b; You et al. 2015). More specifically, MMO games allow (if not invite) players to imbue their avatars with not only their own intrinsic and/or physical characteristics but also with their idealized characteristics (Bessiere et al. 2007). This can be very important for the players and is demonstrated by the fact that players will pay money to customize their avatars via in-game purchases (Cleghorn and Griffiths 2015; Hamari et al. 2017). Furthermore, MMO games are designed to be played for months, or even years (Yee 2014), and to enable constant interaction with other gamers concurrently with experimentation via different roles in the shared space of the video game (Kim and Kim 2010). These functions inevitably reinforce the players’ emotional investment in their online identity (i.e., the avatar) and through their online gameplay (Carter et al. 2012; Stetina et al. 2011; Ng and Wiemer-Hastings 2005; Wei et al. 2012). Subsequently, IGD risk escalates (Ko 2014; Stavropoulos et al. 2016a). Given the identity development challenges related to the period of emerging adulthood (i.e., transition to adult roles; Arnett 2000; Hendry and Kloep 2010; Schwartz et al. 2005; Sussman and Arnett 2014), excessive time invested in these virtual identities (stronger GAR) appears significant for high IGD risk individuals. The dearth of relevant literature suggests further longitudinal investigation is needed to examine the possible fluctuations of the IGD risk effect of GAR during this specific age range. Studies could also be carried out examining the amount of money that gamers are prepared to spend when customizing their avatars in-game as it may be that those with IGD spend significantly greater amounts and that financial problems may also exacerbate the negative consequences of those with IGD.

Depression and Gamer-Avatar Relationship on Internet Gaming Disorder

Findings from the present study demonstrate that emerging adult MMO players who display depressive symptoms, and who identify strongly with their avatars (i.e., the GAR), are at a higher risk of developing IGD behaviors compared to players who may be depressed but identify less strongly with their avatars. This is a novel finding. However, given that this interaction effect has not been previously explored (especially longitudinally), it needs to be interpreted with caution. Consequently, further research is needed to confirm the finding reported in the present study. An individual’s psychological wellbeing, and therefore, their levels of depression, are interconnected to the discrepancy between their actual self and ideal self (i.e., who I am vs. who I would like to be; Higgins et al. 1987). Accordingly, one could assume that more depressed players may project their idealized self onto their avatar, as a way to address their negative feelings about themselves (Bessiere et al. 2007; Ducheneaut et al. 2009; Messinger et al. 2008). This “self-healing” process could cultivate a level of dependency (i.e., my avatar’s happiness compensates for my low mood in real life), increasing both in-game immersion and game play time (Ng and Wiemer-Hastings 2005). The present study’s findings also have potentially important research and clinical implications (especially given that the GAR has not been previously considered as a buffer in the association between depression and IGD). Based on these findings, it is recommended that clinicians explore the relationship between their client’s identity inside and outside of the game in relation to their use of avatars. This could be accompanied by using instruments that have been developed that examine the functions and uses of gaming (such as the Video Game Functional Assessment Scale [Buono et al. 2016]) in addition to those that only assess the negative consequences of gaming.

Future Research, Limitations, Implications, and Conclusions

Findings from the present study suggest several research avenues and implications within the IGD field in addition to those outlined in previous sections. Future research should investigate how individual level characteristics (i.e., gender, age, personality traits, etc.) may moderate (either by exacerbating or buffering) the effect of GAR on the risk of more depressed players developing IGD behaviors. Moreover, and as noted above, prevention and treatment initiatives should target the GAR (i.e., increase the level of understanding of the avatar’s characteristics and how these may complement the user’s real self) to guide cognitive and self-reflective interventions (i.e., increase self-awareness about the discrepancies between real and virtual self). Exploring such relationships provides important experiential information that may be of great use within individual psychotherapy either from a psychodynamic or cognitive-behavioral perspective. In addition to this, future research should investigate in-depth the longitudinal interplay between individual (i.e., age, gender, societal, cultural background, etc.) and gaming-related factors (i.e., game genre, game structure, character development, etc.). Furthermore, increasing the length of the longitudinal design could greatly benefit knowledge considering time-related variations in the associations between depression, GAR, and IGD, as well as the depression-GAR interaction. Given that IGD has been classified as a potentially significant public health risk (APA 2013), it is imperative to develop and expand our understanding of the disorder to better address it.

The present study includes several strengths including (i) a concurrent examination of online and face-to-face participants, (b) a combination of cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses, (c) an emphasis on an underresearched high IGD risk population (emergent adults, MMO gamers), and (d) a focus on both individual and gaming-related factors, as well as their interplay in relation to IGD. There are, however, several limitations that need to be considered. Firstly, IGD was assessed by focusing on one specific group of online gaming genres (i.e., MMO games). There are multiple online gaming genres under the online gaming umbrella, and therefore characteristics of those who play them may vary according to their preferred genre. Secondly, the sample size was relatively small and self-selecting (N = 125); the lack of diversity within the sample size may underrepresent specific demographic groups, suggesting that limitations may exist when extrapolating the results to the emerging adulthood population. Thirdly, the longitudinal design applied only covered a relatively short timeframe. Finally, the present study only used self-report measures which may affect reliability as participant responses can be influenced by mood, memory, social desirability, and situational factors at the time when the assessment was taken (Smith and Handler 2007).

Despite these limitations, the use of advanced statistical techniques (i.e., bootstrapping and maximum likelihood imputation) reinforces the reliability/usability of the findings, which have several research and clinical implications. When considering IGD prevention, the findings suggest that individuals who experience depression and stronger GAR need to be prioritized. In this context—and considering treatment directions—cognitive-behavior therapy may be useful to promote awareness in regard to the use of IGD as a potential maladaptive emotional regulation strategy, emphasizing the significance of the GAR. Furthermore, interpersonal therapy may prove beneficial when exploring the GAR with a depressed emerging adult. This may help to uncover and understand the function of the avatar, thus attenuating IGD risk.

The present study investigated the interplay between offline and online factors in the context of IGD within emerging adults. Findings indicated that both depression and the GAR increase the risk of developing IGD behaviors over time. Furthermore, the GAR was found to exacerbate the relationship between depression and IGD over time. Findings suggest that emerging adults who experience high levels of depression appear to create an idealized version of themselves, which is then projected onto the avatar. This may due to maladaptive emotional regulation strategies. A strong attachment/connection to the avatar may increase gameplay, which in turn may increase IGD risk. This could be a consequence of the way the avatar is implemented as an online identity, and a key game mechanic in the MMO and MMORPG genre. Finally, a depressed player may create an avatar imbued with an idealized self to regulate the disparity with their actual self. Thus, the avatar and its associated identity become particularly significant, resulting in higher game immersion, and longer gameplay sessions, and therefore increasing the risk of developing IGD behaviors. In conclusion, the findings highlight the necessity of investigating both offline and online factors when considering prevention, intervention, and risks associated with IGD.

Notes

The current study is part of a wider project of Federation University Australia that addresses the interplay between individual, Internet, and proximal context factors in the development of Internet gaming disorder symptoms among emerging adults. Instruments used in the data include the following: (1) Internet Gaming Disorder 9-Short Form (Pontes and Griffiths 2015a, b), (2) Beck Depression Inventory—second edition (21 items) (Beck et al. 1996), (3) Beck Anxiety Inventory (21 items) (Beck and Steer 1990), (4) Hikikomori-Social Withdrawal Scale (5 items) (Teo et al. 2015), (5) Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Self-Report Scale (18 items) (Kessler et al. 2005), (6) Ten Item Personality Inventory (Gosling et al. 2003), (7) The Balanced Family Cohesion Scale (7 items) (Olson 2000), (8) Presence Questionnaire (10 items) (Faiola et al. 2013), (9) Online Flow Questionnaire (5 items) (Chen et al. 2000), (10) Self-Presence Questionnaire (Ratan and Hasler 2010), (11) The Gaming-Contingent Self-Worth Scale (12 items) (Beard and Wickham 2016), and (12) Demographic and Internet Use Questions. The battery of questionnaires was utilized for both online and face-to-face data collection. The use of the fitness tracker (Fitbit flex) was used only for face-to-face data collection. Data have not been used in any previous published studies.

To ensure that there were no significant differences between the online and face-to-face samples considering their demographic and Internet use characteristics, as well as the variables used in the present study, independent sample t-tests and chi-square analyses were conducted. Findings did not indicate any significant differences in regards to gender (χ 2 = 0.21, df = 1, p = .89), the type of game genre (i.e., MMOs vs MMORPGs) played (χ 2 = 2.59, df = 1, p = .61), the age of the participants (t = − 0.54, df = 120, p = .59), their years of Internet use (t = 2.35, df = 122, p = .06), their reported level of avatar self-presence (t = 1.09, df = 119, p = .28), and their assessed psychopathological symptoms (depression t = − 0.38, df = 111, p = .70; IGD t = − 0.14, df = 111, p = .89). Therefore, online and face-to-face data (i.e., TP1) were combined (i.e., analyzed together) to investigate cross-sectional questions.

The longitudinal design was assessed for attrition. Assessments’ frequency for each participant varied within a range of 1–3 (Maverage = 2.57). Time point 1 comprised 61 participants, time point 2 comprised 56 participants (8.20% attrition), and time point 3 comprised 43 participants (29.51% attrition). In line with literature recommendations, attrition, in relation to the studied variables, was assessed using Little’s Missing Completely At Random test (MCAR), which was insignificant (MCAR, χ 2 = 1715.79, p = 1.00; Little and Rubin 2014). In order to avoid list-wise deletion, which would reduce the sample’s power, maximum likelihood imputation (five times) of values was applied (Gold and Bentler 2000).

In line with the approval received by the ethics committee of Federation University, the flyers: a) indicated that participants were required to participate on three separate measurement occasions approximately one month apart; b) included an email address to contact the investigators; and c) clearly described the process and stages of the data collection (face-to-face and online). MMO and MMORPG players, aged between 18-29 years old, interested in the study received the Plain Language Information Statement (PLIS). The PLIS clearly indicated that participation was voluntary and that participants could independently decide to withdraw from the study at any point. Individuals who choose to participate were required to provide informed consent.

References

Ackerman, C. M. (2009). The essential elements of Dabrowski’s theory of positive disintegration and how they are connected. Roeper Review, 31(2), 81–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/02783190902737657.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc..

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: a theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychology, 55(5), 469–480. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066X.55.5.469.

Arnett, J. J. (2005). The developmental context of substance use in emerging adulthood. Journal of Drug Issues, 35(2), 235–254. https://doi.org/10.1177/002204260503500202.

Arnett, J. J., Žukauskienė, R., & Sugimura, K. (2014). The new life stage of emerging adulthood at ages 18–29 years: implications for mental health. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1(7), 569–576. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00080-7.

Badrinarayanan, V. A., Sierra, J. J., & Taute, H. A. (2014). Determinants and outcomes of online brand tribalism: exploring communities of massively multiplayer online role playing games (MMORPGs). Psychology and Marketing, 31(10), 853–870. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20739.

Batthyány, D., Müller, K. W., Benker, F., & Wölfling, K. (2009). Computer game playing: clinical characteristics of dependence and abuse among adolescents. Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift, 121(15), 502–509. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00508-009-1198-3.

Baumrind, D., & Moselle, K. A. (1985). A development perspective on adolescent drug abuse. Advances in Alcohol & Substance Abuse, 4(3–4), 41–67. https://doi.org/10.1300/J251v04n03_03.

Beard, C. L., & Wickham, R. E. (2016). Gaming-contingent self-worth, gaming motivation, and internet gaming disorder. Computers in Human Behavior, 61, 507–515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.046.

Beck, A. T., & Steer, R. A. (1990). Manual for the Beck anxiety inventory. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation.

Beck, A., Steer, R., & Brown, G. (1996). BDI-II, Beck depression inventory: manual. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation.

Berkovits, I., Hancock, G. R., & Nevitt, J. (2000). Bootstrap resampling approaches for repeated measure designs: relative robustness to sphericity and normality violations. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 60(6), 877–892. https://doi.org/10.1177/00131640021970961.

Bessiere, K., Seay, A. F., & Kiesler, S. (2007). The ideal elf: identity exploration in World of Warcraft. Cyberpsychology & Behavavior, 10(4), 530–535. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2007.9994.

Billieux, J., Schimmenti, A., & Khazaal, Y. (2015). Are we overpathologizing everyday life? A tenable blueprint for behavioral addiction research. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 4, 119–123. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.4.2015.009.

Biocca, F. (1997). The cyborg’s dilemma: embodiment in virtual environments. Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Cognitive Technology Humanizing the Information Age, USA (pp 12–26). doi:https://doi.org/10.1109/CT.1997.617676.

Blinka, L. (2008). The relationship of players to their avatars in MMORPGs: differences between adolescents, emerging adults and adults. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 2(1), 1–7.

Buono, F. D., Upton, T. D., Griffiths, M. D., Sprong, M. E., & Bordieri, J. (2016). Demonstrating the validity of the Video Game Functional Assessment-Revised (VGFA-R). Computers in Human Behavior, 54, 501–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.08.037.

Caplan, S., Williams, D., & Yee, N. (2009). Problematic internet use and psychosocial well-being among MMO players. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(6), 1312–1319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2009.06.006.

Carter, M., Gibbs, M., & Arnold, M. (2012). Avatars, characters, players and users. Proceedings of the 24th Australian Computer-Human Interaction Conference, Australia (pp 68–71). doi:https://doi.org/10.1145/2414536.2414547.

Chen, H., Wigand, R. T., & Nilan, M. (2000). Exploring web users’ optimal flow experiences. Information Technology & People, 13(4), 263–281. https://doi.org/10.1108/09593840010359473.

Cleghorn, J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2015). Why do gamers buy ‘virtual assets’? An insight in to the psychology behind purchase behaviour. Digital Education Review, 27, 98–117.

Dong, G., Lu, Q., Zhou, H., & Zhao, X. (2011). Precursor or sequela: pathological disorders in people with Internet addiction disorder. PloS One, 6(2). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0014703.

Douglas, A. C., Mills, J. E., Niang, M., Stepchenkova, S., Byun, S., Ruffini, C., et al. (2008). Internet addiction: meta-synthesis of qualitative research for the decade 1996–2006. Computers in Human Behavior, 24(6), 3027–3044. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2008.05.009.

Ducheneaut, N., Yee, N., Nickell, E., & Moore, R. J. (2007). The life and death of online gaming communities. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, USA (p 839). doi:https://doi.org/10.1145/1240624.1240750.

Ducheneaut, N., Wen, M. H., Yee, N., & Wadley, G. (2009). Body and mind: a study of avatar personalization in three virtual worlds. Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, USA (p 1151). doi:https://doi.org/10.1145/1518701.1518877.

Faiola, A., Newlon, C., Pfaff, M., & Smyslova, O. (2013). Correlating the effects of flow and telepresence in virtual worlds: enhancing our understanding of user behavior in game-based learning. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3), 1113–1121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.10.003.

Festl, R., Scharkow, M., & Quandt, T. (2013). Problematic computer game use among adolescents, younger and older adults. Addiction, 108(3), 592–599. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12016.

Galambos, N. L., Barker, E. T., & Krahn, H. J. (2006). Depression, self-esteem, and anger in emerging adulthood: Seven-year trajectories. Developmental Psychology, 42, 350–365. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.350.

George, D., & Mallery, P. (2010). SPSS for Windows step by step: a simple guide and reference 17.0 update (10th ed.). Boston: Pearson.

Gold, M. S., & Bentler, P. M. (2000). Treatments of missing data: a Monte Carlo comparison of RBHDI, iterative stochastic regression imputation, and expectation-maximization. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 7, 319–355. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0703.

Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J., & Swann, W. B. (2003). A very brief measure of the big-five personality domains. Journal of Research in Personality, 37(6), 504–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00046-1.

Griffiths, M. (2005). A ‘components’ model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. Journal of Substance Use, 10(4), 191–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659890500114359.

Griffiths, M. D. (2010). Computer game playing and social skills: a pilot study. Aloma, 27, 301–310.

Griffiths, M. D. (2011). Adolescent gambling. In B. Bradford Brown & M. Prinstein (Eds.), Encyclopedia of adolescence (Vol. 3, pp. 11–20). San Diego: Academic. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-373915-5.00113-3.

Griffiths, M. D. (2015). Gaming addiction and internet gaming disorder. In R. Kowert & T. Quandt (Eds.), The video game debate: Unravelling the physical, social, and psychological effects of video games (pp. 75–93). New York: Routledge.

Griffiths, M. D., Davies, M. N., & Chappell, D. (2004). Demographic factors and playing variables in online computer gaming. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 7(4), 479–487. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2004.7.479.

Griffiths, M. D., Kuss, D. J., Billieux, J., & Pontes, H. M. (2016a). The evolution of internet addiction: a global perspective. Addictive Behaviors, 53, 193–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.11.001.

Griffiths, M. D., van Rooij, A. J., Kardefelt-Winther, D., Starcevic, V., Kiraly, O., Pallesen, S.,. . . Demetrovics, Z. (2016b). Working towards an international consensus on criteria for assessing internet gaming disorder: a critical commentary on Petry et al. (2014). Addiction, 111(1), 167–175. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13057.

Hamari, J., Alha, K., Järvelä, S., Kivikangas, J. M., Koivisto, J., & Paavilainen, J. (2017). Why do players buy in-game content? An empirical study on concrete purchase motivations. Computers in Human Behavior, 68, 538–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.045.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

Hendriks, V. (1990). Addiction and psychopathology: a multidimensional approach to clinical practice. Rotterdam: Erasmus University Rotterdam Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/1765/50810.

Hendry, L. B., & Kloep, M. (2010). How universal is emerging adulthood? An empirical example. Journal of Youth Studies, 13(2), 169–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676260903295067.

Higgins, E. T., Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., Cope, J., Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., & Cope, J. (1987). Self-discrepancy: a theory relating self and affect. Psychological Review, 94(3), 319–340. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.94.3.319.

Hussain, Z., & Griffiths, M. D. (2009a). The attitudes, feelings, and experiences of online gamers: a qualitative analysis. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 12(6), 747–753. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2009.0059.

Hussain, Z., & Griffiths, M. D. (2009b). Excessive use of massively multi-player online role-playing games: a pilot study. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 7(4), 563–571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-009-9202-8.

Jeong, E. J., & Kim, D. H. (2011). Social activities, self-efficacy, game attitudes, and game addiction. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 14(4), 213–221. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2009.0289.

Kardefelt-Winther, D. (2014). A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: towards a model of compensatory internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 31(1), 351–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.059.

Kessler, R. C., Adler, L., Ames, M., Demler, O., Faraone, S., Hiripi, E. V. A., & Ustun, T. B. (2005). The world health organization adult ADHD self-report scale (ASRS): a short screening scale for use in the general population. Psychological Medicine, 35(02), 245–256. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291704002892.

Khantzian, E. J. (1997). The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: a reconsideration and recent applications. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 4(5), 231–244. https://doi.org/10.3109/10673229709030550.

Kim, M. G., & Kim, J. (2010). Cross-validation of reliability, convergent and discriminant validity for the problematic online game use scale. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(3), 389–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2009.11.010.

King, D. L., & Delfabbro, P. H. (2014). Internet gaming disorder treatment: a review of definitions of diagnosis and treatment outcome. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 70(10), 942–955. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22097.

King, D. L., & Delfabbro, P. H. (2016). The cognitive psychopathology of internet gaming disorder in adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44, 1635–1645. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-016-0135-y.

King, D. L., Delfabbro, P. H., & Griffiths, M. D. (2013a). Video game addiction. In P. M. Miller (Ed.), Comprehensive addictive behaviors and disorders: vol. 1. Principles of addiction (pp. 819–825). San Diego: Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-398336-7.00082-6.

King, D. L., Haagsma, M. C., Delfabbro, P. H., Gradisar, M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2013b). Toward a consensus definition of pathological video-gaming: A systematic review of psychometric assessment tools. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(3), 331–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2013.01.002.

Klimmt, C., Hefner, D., & Vorderer, P. (2009). The video game experience as “true” identification: a theory of enjoyable alterations of players’ self-perception. Communication Theory, 19(4), 351–373. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2009.01347.x.

Ko, C. H. (2014). Internet gaming disorder. Current Addiction Reports, 1(3), 177–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-014-0030-y.

Ko, C. H., Yen, J. Y., Yen, C. F., Chen, C. S., & Chen, C. C. (2012). The association between internet addiction and psychiatric disorder: a review of the literature. European Psychiatry, 27(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.04.011.

Kowert, R., & Quandt, T. (Eds.). (2015). The video game debate: unravelling the physical, social, and psychological effects of video games. New York: Routledge.

Kuss, D. J. (2013). Internet gaming addiction: current perspectives. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 6, 125–137.

Kuss, D. J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2012a). Internet gaming addiction: a systematic review of empirical research. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 10(2), 278–296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-011-9318-5.

Kuss, D. J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2012b). Online gaming addiction in children and adolescents: a review of empirical research. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 1(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1556/JBA.1.2012.1.1.

Lee, S. Y., & Xia, Y. M. (2006). Maximum likelihood methods in treating outliers and symmetrically heavy-tailed distributions for nonlinear structural equation models with missing data. Psychometrika, 71(3), 565–585. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11336-006-1264-1.

Lemmens, J. S., Valkenburg, P. M., & Peter, J. (2011). Psychosocial causes and consequences of pathological gaming. Computers in Human Behavior, 27(1), 144–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.07.015.

Little, R. J. A., & Rubin, D. B. (2014). Statistical analysis with missing data. Hoboken: Wiley.

Masten, A. S. (2001). Ordinary magic. Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist, 56(3), 227–238. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.227.

Masten, A. S. (2014). Invited commentary: resilience and positive youth development frameworks in developmental science. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(6), 1018–1024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-014-0118-7.

Meng, J., Williams, D., & Shen, C. (2015). Channels matter: multimodal connectedness, types of co-players and social capital for multiplayer online battle arena gamers. Computers in Human Behavior, 52, 190–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.06.007.

Messinger, P., Ge, X., Stroulia, E., Lyons, K., Smirnov, K., Bone, M., & Van Rees, M. (2008). On the relationship between my avatar and myself. Journal of Virtual Worlds Research, 1(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.05.013.

Muller, K. W., Janikian, M., Dreier, M., Wolfling, K., Beutel, M. E., Tzavara, C.,. .. Tsitsika, A. (2015). Regular gaming behavior and internet gaming disorder in European adolescents: results from a cross-national representative survey of prevalence, predictors, and psychopathological correlates. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 24(5), 565–574. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-014-0611-2.

Ng, B. D., & Wiemer-Hastings, P. (2005). Addiction to the internet and online gaming. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 8(2), 110–113. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2005.8.110.

Olson, D. H. (2000). Circumplex model of marital and family systems. Journal of Family Therapy, 22(2), 144–167. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6427.00144.

Ortiz de Gortari, A. B., & Griffiths, M. D. (2013). Altered visual perception in game transfer phenomena: An empirical self-report study. International Journal of Human Computer Interaction, 30(2), 95–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2013.839900.

Ortiz de Gortari, A. B., & Griffiths, M. D. (2014). Auditory experiences in game transfer phenomena. International Journal of Cyber Behavior, Psychology and Learning, 4(1), 59–75. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijcbpl.2014010105.

Ortiz de Gortari, A. B., & Griffiths, M. D. (2016). Prevalence and characteristics of game transfer phenomena: a descriptive survey study. International Journal of Human Computer Interaction, 32, 470–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2016.1164430.

Pandina, R. J., Labouvie, E. W., Johnson, V., & White, H. R. (1990). The relationship between alcohol and marijuana use and competence in adolescence. Journal of Health & Social Policy, 1(3), 89–108. https://doi.org/10.1300/J045v01n03_06.

Petry, N. M., Rehbein, F., Gentile, D. A., Lemmens, J. S., Rumpf, H. J., Mossle, T.,. .. O'Brien, C. P. (2014a). An international consensus for assessing internet gaming disorder using the new DSM-5 approach. Addiction, 109(9), 1399–1406. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12457.

Petry, N. M., Rehbein, F., Gentile, D. A., Lemmens, J. S., Rumpf, H. J., Mossle, T., et al. (2014b). Moving internet gaming disorder forward: A reply. Addiction, 109(9), 1412–1413. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12653.

Petry, N. M., Rehbein, F., Ko, C.-H., & O’Brien, C. P. (2015). Internet gaming disorder in the DSM-5. Current Psychiatry Reports, 17, 72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-015-0610-0.

Pontes, H. M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2014). Assessment of internet gaming disorder in clinical research: past and present perspectives. Clinical Research and Regulatory Affairs, 31(2–4), 35–48. https://doi.org/10.3109/10601333.2014.962748.

Pontes, H. M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2015a). Internet gaming disorder and its associated cognitions and cognitive-related impairments: a systematic review using PRISMA guidelines. Revista Argentina de Ciencias del Comportamiento, 7, 102–118 Retrieved from https://revistas.unc.edu.ar/index.php/racc/index.

Pontes, H. M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2015b). Measuring DSM-5 internet gaming disorder: Development and validation of a short psychometric scale. Computers in Human Behavior, 45, 137–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.12.006.

Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42(1), 185–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273170701341316.

Pringle, H. M. (2015). Conjuring the ideal self: an investigation of self-presentation in video game avatars. Press Start, 2, 1–20 Retrieved from http://press-start.gla.ac.uk/index.php/press-start/index.

Rao, C. R., & Toutenburg, H. (1995). Linear models. New York: Springer.

Ratan, R. (2013). Self-presence, explicated: Body, emotion, and identity extension into the virtual self. In R. Lippicini (Ed.), Handbook of Research on Technoself (pp. 322–336). Hershey: IGI Global.

Ratan, R. A., & Dawson, M. (2015). When mii is me: a psychophysiological examination of avatar self-relevance. Communication Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650215570652.

Ratan, R., & Hasler, B. S. (2010). Exploring self-presence in collaborative virtual teams. PsychNology Journal, 8(1), 11–31.

Ream, G. L., Elliott, L. C., & Dunlap, E. (2013). Trends in video game play through childhood, adolescence, and emerging adulthood. Psychiatry Journal, 2013, 301460. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/301460.

Rehbein, F., Psych, G., Kleimann, M., Mediasci, G., & Mößle, T. (2010). Prevalence and risk factors of video game dependency in adolescence: results of a German nationwide survey. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 13(3), 269–277. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2009.0227.

Schwartz, S. J., Côté, J. E., & Arnett, J. J. (2005). Identity and agency in emerging adulthood: two developmental routes in the individualization process. Youth & Society, 37(2), 201–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X05275965.

Scott, J., & Porter-Armstrong, A. P. (2013). Impact of multiplayer online role-playing games upon the psychosocial well-being of adolescents and young adults: reviewing the evidence. Psychiatry Journal, 2013, 464685. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/464685.

Smahel, D., Blinka, L., & Ledabyl, O. (2008). Playing MMORPGs: connections between addiction and identifying with a character. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 11(6), 715–718. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2007.0210.

Smith, S. R., & Handler, L. (Eds.). (2007). The clinical practice of child and adolescent assessment. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Stanley, P. (2015). The risk and resilience framework and its implications for teachers and schools. Waikato Journal of Education, 14(1), 139–153. 10.15663/wje.v14i1.248.

Stavropoulos, V., Gentile, D., & Motti-Stefanidi, F. (2016a). A multilevel longitudinal study of adolescent Internet addiction: the role of obsessive–compulsive symptoms and classroom openness to experience. The European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 13(1), 99–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2015.1066670.

Stavropoulos, V., Kuss, D., Griffiths, M., & Motti-Stefanidi, F. (2016b). A longitudinal study of adolescent internet addiction: the role of conscientiousness and classroom hostility. Journal of Adolescent Research, 31(4), 442–473. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558415580163.

Stavropoulos, V., Kuss, D. J., Griffiths, M. D., Wilson, P., & Motti-Stefanidi, F. (2017). MMORPG gaming and hostility predict internet addiction symptoms in adolescents: an empirical multilevel longitudinal study. Addictive Behaviors. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.09.001.

Stetina, B. U., Kothgassner, O. D., Lehenbauer, M., & Kryspin-Exner, I. (2011). Beyond the fascination of online-games: probing addictive behavior and depression in the world of online-gaming. Computers in Human Behavior, 27, 473–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.09.015.

Stone, A. L., Becker, L. G., Huber, A. M., & Catalano, R. F. (2012). Review of risk and protective factors of substance use and problem use in emerging adulthood. Addictive Behaviors, 37, 747–775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.02.014.

Sussman, S., & Arnett, J. J. (2014). Emerging adulthood: developmental period facilitative of the addictions. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 37(2), 147–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278714521812.

Swendsen, J. D., & Merikangas, K. R. (2000). The comorbidity of depression and substance use disorders. Clinical Psychology Review, 20(2), 173–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(99)00026-4.

Teo, A. R., Fetters, M. D., Stufflebam, K., Tateno, M., Balhara, Y., Choi, T. Y., & Kato, T. A. (2015). Identification of the hikikomori syndrome of social withdrawal: Psychosocial features and treatment preferences in four countries. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 61(1), 64–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764014535758.

Volkow, N. D. (2004). The reality of comorbidity: depression and drug abuse. Biological Psychiatry, 56, 714–717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.07.007.

Vollmer, C., Randler, C., Horzum, M. B., & Ayas, T. (2014). Computer game addiction in adolescents and its relationship to chronotype and personality. SAGE Open, 4(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244013518054.

Wei, H. T., Chen, M. H., Huang, P. C., & Bai, Y. M. (2012). The association between online gaming, social phobia, and depression: an internet survey. BMC Psychiatry, 12, 92. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-12-92.

Winer, E. S., Cervone, D., Bryant, J., McKinney, C., Liu, R. T., & Nadorff, M. R. (2016). Distinguishing mediational models and analyses in clinical psychology: atemporal associations do not imply causation. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 72(9), 947–955. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22298.

Wolfendale, J. (2007). My avatar, myself: virtual harm and attachment. Ethics and Information Technology, 9(2), 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-006-9125-z.

Wood, R. T. A., & Griffiths, M. D. (2007). A qualitative investigation of problem gambling as an escape-based coping strategy. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 80, 107–125. https://doi.org/10.1348/147608306X107881.

Yee, N. (2006a). The demographics, motivations, and derived experiences of users of massively multi-user online graphical environments. Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, 15, 309–329. https://doi.org/10.1162/pres.15.3.309.

Yee, N. (2006b). The psychology of massively multi-user online role-playing games: Motivations, emotional investment, relationships and problematic usage. Avatars at Work and Play: Collaboration and Interaction in Shared Virtual Environments, 34, 187–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-3898-4_9.

Yee, N. (2014). The Proteus paradox: How online games and virtual worlds change us-and how they don't. Orwigsburg: Yale University Press.

Yen, J. Y., Ko, C. H., Yen, C. F., Wu, H. Y., & Yang, M. J. (2007). The comorbid psychiatric symptoms of Internet addiction: attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), depression, social phobia, and hostility. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41(1), 93–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.02.002.

You, S., Kim, E., & Lee, D. (2015). Virtually real: exploring avatar identification in game addiction among massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPG) players. Games and Culture, 1(16). https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412015581087.

Young, K. S. (2009). Internet addiction. American Behavioral Scientist, 4, 402–415.

Young, K. S., & Rodgers, R. C. (1998). The relationship between depression and internet addiction. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 1(1), 25–28. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.1998.1.25.

Funding

There was no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TB contributed to the literature review, hypothesis formulation, data collection and analyses, and the structure and sequence of theoretical arguments.

VS contributed to the literature review, hypothesis formulation, data collection and analyses, and the structure and sequence of theoretical arguments.

LL contributed to the data collection and analyses.

BA contributed to the data collection and analyses.

MG contributed to the theoretical consolidation of the current work, and revised and edited the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Standards—Animal Rights

All procedures performed in the study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Appendix

Appendix

A1. Analytical assumptions

The presence of outliers in the data was assessed by calculating the Mahalanobis distance (MD). In regard to the cross-sectional analysis, three outlier values were detected with a MD = 21.47, p = .00001; MD = 13.42, p = .00025; and MD = 11.57, p = .00067, respectively. In regard to the longitudinal analysis, two outlier values were detected with a MD = 17.44, p = .00003, and MD = 14.90, p = .00011, respectively. Following literature recommendations, any MD that referred to a probability lower than 0.001 was defined as an outlier, was treated as a missing value, and was substituted with maximum likelihood (five times) imputation based on all the available variables (Lee and Xia 2006).

Assumptions of linearity, multivariate normality, and homoscedasticity were further assessed (Rao and Toutenburg 1995). Given that only one independent variable was used, multicollinearity was not assessed. Linearity assumption was tested with probability-probability plot (PP). All variables used in both cross-sectional and longitudinal data did not violate the assumption of linearity. Normality was checked by measuring skewness and kurtosis with values below − 2 or above + 2 addressed with bootstrapping-1000 resamples (Berkovits et al. 2000). In order to assess homoscedasticity, scatterplots of regression standardized residuals, and the regression standardized predicted values were implemented (George and Mallery 2010). Both cross-sectional and longitudinal data scatterplots did not indicate any violations to the assumption of homoscedasticity.

A2. Correlations and descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations of cross-sectional data can be found in Table 2. The results revealed that higher depression scores and GAR scores are correlated with higher IGD scores.

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations, from longitudinal data, can be found in Table 3. The results indicate that higher depression scores are correlated with higher IGD scores. Both depression scores and IGD scores were significantly related to each other on all time points. In addition to this, both GAR scores and IGD scores are also significantly related across all time points.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Burleigh, T.L., Stavropoulos, V., Liew, L.W.L. et al. Depression, Internet Gaming Disorder, and the Moderating Effect of the Gamer-Avatar Relationship: an Exploratory Longitudinal Study. Int J Ment Health Addiction 16, 102–124 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-017-9806-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-017-9806-3