Abstract

Empowering students to express their own voices is an important educational aim; yet, the exploration of sensitive topics in discussion-based activities poses particular challenges concerning the realisation of student voices. In consideration of this issue, we analyse how one teacher and his lower secondary students coped with such challenges by using microblogging technology designed specifically for educational purposes. We examine the extent to which this technology affords extended conditions for the aforementioned realisation when ideas about the body and sexuality are presented, shared and justified in a science lesson. Our results illustrate how microblogging contributes to the emergence of new communicative principles of sequentiality that are not present in classroom discussions without digital technology. We argue that these principles are central to why students are ultimately being provided a space for participation wherein conditions for realising their voices about a sensitive topic in Science are extended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Dialogic approaches to teaching and learning are gaining momentum in science education and beyond (Aguiar 2016). While recognising that students learn in many ways, dialogic approaches place particular emphasis on communication through dialogue as both a means to share and develop knowledge and understanding in the classroom and an educational goal in itself (Mercer, Wegerif and Major 2019). Many scholars within this relatively diverse field of teaching and learning have been especially concerned with empowering students to express their own voices in classroom discussions (Segal and Lefstein 2016). Educational scholars recognise that students must always relate to institutionally given types of knowledge in formal schooling, which indicates that dialogues in schools should be viewed as institutional talk that emerges in specific situations and is intended to serve normative goals (Furberg and Ludvigsen 2008). Nevertheless, dialogic approaches highlight that the authoritative voice of a teacher or textbook should not be the only resource present in this environment (Mortimer and Scott 2003). Concerns about the voices of students are not new in educational research and reform (Cook-Sather 2014), but dialogic approaches position the interplay of voices in a discourse at the centre of the meaning-making process (Roth 2009). In this sense, empowering students to express their own voices instead of merely reproducing or animating those of others (Goffman 1981) is an important step in the process of learning to reason about a given topic in the school context.

Despite teachers’ efforts to promote participation in classroom discussions, the realisation of student voices in this institutional context can be challenging. It may be particularly difficult to encourage learners to engage in face-to-face exchanges if the topic is perceived as complex and sensitive. Science education offers numerous opportunities to grapple with such topics when, for instance, students are expected to express themselves and reason about the body and sexuality (Lundin 2014). An overwhelming amount of information on the body and sexuality is readily accessible on the internet; however, surfing the net also introduces students to a range of challenges in terms of finding and evaluating information of various degrees of trustworthiness. Moreover, cognitive biases amplified by algorithms may impair judgement skills and diminish the capability of users to explore diverse perspectives (Schweiger, Oeberst and Cress 2014). Although learning to operate critically on the web is important, we argue that the ability to express and justify one’s ideas and recognise the views of others through dialogue in the institutional context of the classroom carries special educational value under the described circumstances. Thus, we must investigate how to create a space for participation through dialogue in science classrooms when the topic of discussion is nontrivial.

Research has illustrated the potential of digital technology to facilitate various forms of participation and student engagement with content in school subjects (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine 2018). Microblogging is one specific technology that has demonstrated promising advantages for affecting the dynamics of communication through its transformation of interactional logic (Ludvigsen, Ness and Timmis 2019). However, there is scarce knowledge of how such technology can function as a co-mediator in supporting the realisation of student voices in classroom discussions on science education topics that are perceived as sensitive. Thus, the present research explores an implementation of microblogging technology in a classroom and the extent to which this application may afford extended conditions for the realisation of student voices.

Based on data from a design-based project entitled Digital Dialogues Across the Curriculum (DIDIAC), we analyse how one teacher and his lower secondary students (aged 12–13 years) used educational microblogging technology to cope with obstacles to the realisation of students’ voices in presenting, sharing and justifying ideas about the body and sexuality in a science lesson. Through this case, we address the following questions:

- RQ1::

-

How can microblogging be enacted in a science classroom where sensitive topics are discussed?

- RQ2::

-

To what extent can microblogging be enacted in ways that afford extended conditions for the realisation of student voices?

In the following section, we present the study’s theoretical and conceptual underpinnings, including insights from relevant research. Then, we describe the empirical context and the methods applied for our analysis of the case study. Finally, we discuss how this specific case may inform research on technology usage and opportunities for realising student voices in the classroom.

The concept of voice and the ‘interplay of voices’

Alison Cook-Sather (2006) has carefully analysed how the term ‘student voice’ has been evoked and applied in educational research and reform since the early 1990s in countries such as Australia, Canada, England and the United States. Although there is no definite conception of the term, much of the varied work on this concept revolves around democratic ideals. Such ideals, which highlight the legitimate role of students in using their perspectives and opinions to actively shape their future (Holdsworth 2000), represent values and norms that correspond with particular conceptions of how people learn and learn to think (Wertsch 1991). These conceptions are shared by dialogic approaches to teaching and learning (Mercer and Littleton 2007). Dialogic approaches to education are diverse (Lefstein and Snell 2014), but they share an emphasis on active student involvement through dialogue for learning and learning to think. In line with a sociocultural stance on the human mind and action, this participatory ethos is considered a result of the continuous development and maintenance of communicative norms that encourage students to speak and reason together. The forerunners of such norms, which consist of explicit reminders intended to guide participation in the classroom, are sometimes referred to as ‘ground rules’ (Littleton and Mercer 2007, p. 57).

In addition, certain strands of thought within dialogic education have been especially concerned with empowering students to express their own voices (Segal and Lefstein 2016). These strands are rooted in perspectives which are typically associated with the classic writings of Mikhail Bakhtin (1981). In Bakhtinian terminology, a voice cannot be reduced to vocal-auditory signals, as it encompasses ‘the broader issues of a speaking subject’s perspective, conceptual horizon, intention, and world view’ (Wertsch 1991, p. 51). This view renders the concept of the voice fundamentally situated and relational, as any perspective of the world is always particular in relation to something else—that is, any voice is always related to other voices in an interplay or dialogue of voices. According to this position, this interplay of voices, wherein two or more voices come into contact and are held together in the tension of a dialogue, is at the centre of the meaning-making process in a discourse (Wegerif 2013). Most importantly, it follows that the richness and potential of collective meaning-making reflect the extent to which different voices and resources are given the opportunity to connect. This task is vital yet difficult to realise in science classroom discussions as specific forms of institutional activity.

Aliza Segal and Adam Lefstein (2016) have recently proposed a conceptual lens for analysing the realisation of voices in a classroom discourse. Building on the works of Bakhtin (1981), Dell Hymes (1996) and Jan Blommaert (2005), the authors have clarified four conditions for such realisation. First, for students to exercise their voices, they must be granted an opportunity to speak. In this context, the act of speaking is not limited to talking and extends to any form of the expression of ideas. Second, students must have the opportunity to express their own ideas—as opposed to only animating the ideas of others. Third, students must be provided a chance to speak in their own terms. In this regard, it is imperative to consider what is talked about, with whom one speaks and for which purposes, as the specific institutional context of the classroom reflects specific discursive genres. Finally, students must be allowed to be heeded by others, which requires that someone is listening and acknowledging that their ideas are legitimate and valuable. A student can, in principle, speak her own ideas in her own terms, but if others are not oriented towards what she are saying, then no real interplay of voices can occur.

In the next section, we identify challenges in discussion-based activities that concern the realisation of voices. Although such challenges may relate to many aspects of classroom discussion activities, we focus exclusively on two that are fundamental and intertwined: the dynamics of communication that are innate to a face-to-face setting and perceptions of the nature of a topic of exploration.

Challenges to the realisation of voices in discussion-based classroom activities

Communication dynamics in face-to-face discussions unfold within a very narrow timeframe. For example, the acts of speaking, listening, social positioning, timing and pacing occur ‘moment to moment’ (Jordan and Henderson 1995). Here, a superordinate challenge in realising voices in face-to-face discussions in the classroom is that only one person can speak at any given moment, and the other people are always positioned as listeners (and potential speakers) when someone is speaking. This strong quantitative asymmetry between speaking and listening creates a paradox: when a higher number of students is present, and there is a stronger potential for different students to take the floor and publicly participate in an interplay of voices, it actually becomes less likely that any particular student will do so. This paradox relates to the first condition for realising voices in Segal and Lefstein’s (2016) conceptual lens, namely being given the opportunity to speak.

While many students express themselves verbally in classroom discussions, only those who take the floor to meaningfully participate in moment-to-moment interactions must adhere to certain communicative principles (Linell 1998). First, in a classroom discussion, organisation is fundamentally sequential. The principle of sequentiality reveals how the meaning of specific contributions is largely dependent upon their position in an ongoing and temporary sequence of contributions. Therefore, the act of positioning a contribution in such a dynamic sequence is not carried out by an individual in isolation; rather, it involves timing, pacing and coordination between actors. Second, the principle of joint construction accentuates such processes when participants act collectively through mutually coordinated actions and interactions. Finally, the principle of act-activity interdependence foregrounds the situatedness of contributions in a particular activity genre. Since an activity genre refers to how activities are traditionally conducted in a social context, the concept extends beyond discourse to include particular participants, roles, intentions and purposes as well as non-communicative activities. These principles are reflexively connected and ‘at work’ simultaneously when individuals participate in spoken dialogue (Linell 1998).

Although these principles are necessary to enable collective meaning-making in a face-to-face situation, they pose challenges to realising one’s voice in a discussion in the classroom. In this activity genre and context, for example, any current speaker receives attention and evaluation from all others in situ. Thus, the speaker must be mindful of timing, pacing and coordination, and their social position and communicative repertoire are fully apparent to many listeners as they articulate their ideas. Students may be triggered by this ‘spotlight experience’ or tend to withdraw. Some might choose to express their ideas and may be heeded by others (the first and fourth conditions for realising one’s voice) but lack the chance to speak their own ideas in their own terms (the second and third conditions for realising one’s voice).

Moreover, in a lively classroom discussion, one can expect more or less clearly articulated ideas and arguments to ‘dance’ between speakers, which creates a complex situation for someone who is considering taking the floor. A contribution that might seem relevant at one time may be significantly more difficult to situate in a cumulative line of reasoning only a few moments later. Thus, a student might want to share her point of view in a discussion but never secure the opportunity to situate it successfully in a sequence of contributions. The upshot is the decision to remain a listener and, accordingly, a failure to realise her voice publicly.

These challenges are innate to the interactional dynamics of a standard face-to-face discussion activity. In line with Per Linell (1998), who has emphasised the interdependence between verbal actions and the contexts in which they are situated, we propose that the nature of a topic for exploration in the institutional context of the classroom can intensify these communicative challenges. For example, topics which are perceived as sensitive may magnify the spotlight experience in a face-to-face discussion and impose an additional emotional constraint on the intellectually difficult task of logically situating one’s point of view in a sequence of contributions at the right time.

These points can be actualised in empirical findings on how teachers and students cope with emotionally laden topics in classroom discussions. For instance—and perhaps unsurprisingly—research has illustrated that such topics increase students’ awareness and fear of how they are perceived and judged by their peers and teachers, which in turn reduces their willingness to express themselves publicly (Lusk and Weinberg 1994). In such contexts, students often need more support from the teacher to involve themselves verbally. Although students may view teachers as trusted sources of information and authority (Gregory and Ripski 2008), teachers vary considerably in their degree of comfort with facilitating discussions about sensitive and controversial topics (Cohen, Byers, Sears and Weaver 2004). Many feel underprepared and question their own expertise when approaching an emotionally laden and complex social topic that can prompt unpredictable and challenging reactions from students (Oulton, Day, Dillon and Grace 2004).

In science education, the topic of the body and sexuality is exemplary of a complex and sensitive social and biological subject of discussion where students might be expected to express themselves and actively engage in shared knowledge construction. Extensive educational research has strongly linked this topic to pre-defined normative imperatives and the cultivation of student attitudes and behaviours that reduce pregnancy rates and sexually transmitted diseases (Lehmiller 2017). However, there is increasing recognition in many countries that more comprehensive sex education is needed (UNESCO 2018). Scholars have also argued that a fuller understanding of social and emotional issues is essential to combat sexual assault and promote positive attitudes about consent (Richmond and Peterson 2020). Such an approach compounds the complexity of discussions in science classrooms because it highlights the perspectives of students and their concerns as vital knowledge resources that must be pooled and integrated with the curriculum content. Related to this, Willemijn Krebbekx (2018) has noted that few studies have explored how knowledge about the body and sexuality is actually produced and integrated in classrooms at the interactional level (as opposed to studying the effects of interventions or a policing practice; for a notable exception, see Lundin 2014).

As mentioned in the introduction, educational research has displayed a growing interest in the potential role of digital technology in creating spaces for student voices and participation in the classroom (Manca, Grion, Armellini and Devecchi 2017). In the rapidly evolving ecologies of digital possibilities, microblogging is one technology that has proven to be particularly suitable for transforming the logic of interactional work in classroom discussions (Rasmussen and Hagen 2015). According to previous research, even though microblogging is not specifically designed for conversation, blogs and tweets often initiate such exchanges (Gao, Luo and Zhang 2012). However, since the existing studies were conducted with older students, less is known about the power of such innovations to provide space for the voices of secondary students when the nature of a topic renders its discussion especially difficult. Understanding the role of technology in these contexts requires an adequate conceptual stance. In the following section, we theorise how digital technology can support classroom activities with reference to the concepts of affordance and mediated action.

Analysing the role of digital technologies in classroom activities: affordances and mediated action

Studies on applications of technology for human learning have extensively employed the concept of ‘affordance’, which James G. Gibson (1979) originally defined as a property of an object that enables a person who uses the object to relate to it in a particular way. In this sense, an affordance materialises in human activities and concerns both the physical properties of an object and how it is acted upon. Therefore, the affordance of an object is relative to the agent who acts upon it. A classic illustration of this point is how a doorknob affords its users a way to twist and push (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine 2018). In a sense, what the doorknob affords is objective and physical; its particular shape, location and mechanics are all physical properties. But the act of twisting and pushing are also facts of behaviour. Gibson (1979) has noted that ‘an affordance points both ways, to the environment and to the observer’ (p. 129).

In revisiting the classic works of Gibson (1979), James Greeno (1994) has suggested that affordance, as a property of whatever an agent interacts with, should be treated as a condition for constraints to which actors become gradually attuned. This perspective both nuances and expands Gibson’s (1979) original work. In connection to the use of digital technology to support the realisation of student voices in discussion-based activities, Greeno’s (1994) perspective recognises that such an innovation provides action possibilities that can become affordances for the realisation of student voices depending on the actions of agents and the applied pedagogy.

Louis Major and Paul Warwick (2019) have further stressed that affordances, as meaning potentials, must be utilised in practice to reach a desired activity goal. In their discussion of how to understand the benefits of digital technology for dialogic teaching and learning, these authors have asserted that the affordances of digital technology for this purpose stem from the dynamic interplay amongst the object, pedagogy (i.e. plans and interactions) and usage of the object. Figure 1 visualises the relationships between action possibilities, dialogic pedagogy and enacted affordances.

Source: Major and Warwick 2019, p. 401)

Connecting action possibilities and enacted affordances (

This model is more aligned with a mediated action perspective (Wertsch 1991) and the work of Greeno (1994) than with the original work of Gibson (1979). When applied to a classroom discussion in which the teacher uses a digital tool to support the realisation of students’ voices, the model illustrates the dynamic interplay amongst the tool, agent and culture. Furthermore, it reflects that mediating tools have transformative power; in the example of a teacher acting with digital tools in a classroom discussion, the devices may co-structure (together with other mediating tools in the environment) how we think about pedagogy, which can subsequently influence the enactment of affordances for specific educational purposes.

The concept of affordances is valuable for illuminating the abilities of digital technology to support dialogic classroom activities, as it directs attention to possibilities that a tool may or may not afford depending on its pedagogical enactment to reach a desired goal. When the tool is enacted, the resulting process can be described in terms of triadic structures of interaction involving two or more people and the tool in a particular institutional context (Ludvigsen and Steier 2019). In the following section, we briefly explain the design-based project DIDIAC, which is foundational to the pedagogy and technological components of this study. We then provide a detailed account of our case selection and participants, data sources and analytical approach to the data analysis.

Empirical context and methods

This research is based on data from the international design-based research project DIDIAC, which primarily aimed to explore the development of dialogic classroom practices supported by microblogging technology in lower secondary classrooms. The project involved two core components: a teacher development programme and the microblogging tool Talkwall. The former was based on the ‘Thinking Together’ approach (Mercer and Littleton 2007). Between September and December 2017, teachers participated in four workshops to learn about the key ideas of this approach, which emphasises the importance of developing ground rules to encourage exploratory talk in which reasoning is explicit and students engage critically and constructively with one another’s thinking (Mercer and Littleton 2007).

In addition, the teachers were encouraged to experiment with the microblogging tool Talkwall, which members of the DIDIAC team originally designed and developed for the realisation of dialogic ideals in the classroom. Talkwall is a browser-based tool that can be used on any computer, tablet or smartphone with an internet connection. The teachers experimented with Talkwall to identify when and how particular ways of using it could enrich learning in various activities. The basic interface of Talkwall has two distinct features that are shared by all participants: a feed on the left side and a wall in the middle of the screen (see Fig. 2). Users can author blog contributions that are automatically accessible to all participants through the feed, and they can select their own contribution or those of others in the feed to ‘pin’ to the wall. Additionally, users have their own walls where they can organise the contributions as they please and to which the teacher has access.

Case selection and participants

In the review of the DIDIAC material, which covered a range of uses of microblogging technology across subjects in lower secondary schools in Norway and England, the science lesson on the body and sexuality attracted the interest of the research team for several reasons. First, it was the only lesson in which the teacher purposefully used microblogging to mitigate the challenges associated with involving students in collective exploration and reasoning about a sensitive topic. In an e-mail correspondence with the first author a few days prior to the lesson, the teacher explained,

I absolutely believe that Talkwall can remove some of students’ barriers to express themselves. I want us to reach an agreement that various porn magazines and internet sites are not the best sources for good information on body and sexuality.

Second, the teacher repeatedly encouraged his students to express their opinions and ideas throughout the lesson. This approach signalled to the students that their thinking and ideas were valuable and important, and it directly invited them to share their concerns in the discussion. Third, there was a high proportion of interactivity on the microblogging platform relative to the face-to-face interaction, which not only reflects that microblogging was instrumental to the interactional work but also suggests that face-to-face communication may have been especially difficult. The teacher was a relatively young male in his early 30 s and exhibited a trusting relationship with his students. In terms of technology use, he was generally exploratory in his approach, and other teachers often asked him for technical support. During the lesson, 27 students (aged 12–13 years) were encouraged to express themselves and their reasoning about the body and sexuality. In the Norwegian national curriculum, the topic of the body and sexuality relates to the general education aim of developing the communication skills of students (Ministry of Education and Research 2020) as well as competence aims that are specific to science and seek to equip students to discuss issues of sexuality, diversity of sexual orientations, prevention, abortion and sexually transferable infections (The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training 2020).

Data and analytical approach

The primary data source for this research was video recordings, which were supplemented by field data and log data from Talkwall. The lesson was video recorded with two cameras that were operated by a dedicated researcher and strategically positioned to capture as much physical interactivity as possible. Another researcher observed from the back of the classroom for the entire lesson and produced field notes. The video-recorded lessons were transcribed verbatim, and the level of detail in the transcripts corresponds to the depth of the analysis. The transcripts were translated, which caused some loss of nuances, such as local slang; nevertheless, other important details, such as pauses, attentive signalling and pointing, were possible to convey. We anonymised the participants in the talk extracts and the groups in the Talkwall illustrations.

The types of interactivity (i.e. writing a blog or ‘pinning’ a blog from the feed to the wall) in Talkwall were automatically registered and saved to a computer server, after which these data were integrated and synced with transcriptions of the verbal communication via software for mobile devices developed in the research project. Finally, all data were integrated into a specially designed Excel spreadsheet for further in-depth analysis. A combination of analytical approaches was used to meticulously examine the rich empirical data with regard to our research questions (Silverman 2010).

First, to clarify the evolution of the described activities, the mode of enacting microblogging in the classroom and the social climate, we combined field notes with video recordings to frame the activities. Second, we explored the Talkwall activity both at a general level and in terms of specific blog contributions. The aggregated expressions of the Talkwall activity were differentiated, compared and measured as well as visualised with charts to illustrate how participants performed general types of action in Talkwall. Such data can reveal conditions for realising voices. Since the extent to which a blog format actually conveys student voices demands closer consideration of specific blog posts, the students’ contributions were extracted and analysed as responses to the task formulated by the teacher in Talkwall. We focused on the scope of variations in terms of blog length, content, precision, use of textual means and voice. Third, to capture the complex and dynamic interplay between the participants and artefacts and the oral and the written interactions, we probed the moment-to-moment classroom interactions during the lesson (Mercer 2004). After repeated viewings and close readings of the transcript from the selected video-recorded lesson, we concentrated on how the teacher and his students structured and coordinated their actions to produce a coherent interaction, which was mediated by both verbal interaction and digital technology. Thus, the analysis centred on the specific orientation of the teacher and the students. Finally, based on Segal and Lefstein’s (2016) four conditions, we assessed the extent to which the activities allowed for the realisation of voices as part of institutional activities.

Analysis

In this section, we provide the necessary context before presenting our analysis. The lesson was 45 min in duration and focused on the topic of the body and sexuality. It was the first lesson to address this topic, which students continued to work on in the subsequent weeks. Talkwall was utilised throughout the lesson (see Fig. 2 for an overview of Talkwall functionalities and Appendix 1 for an overview of the lesson). Our analysis chronologically follows the activities early in the lesson to provide a sense of their progression and interdependence. Accordingly, the qualitative and quantitative data are not presented separately but instead integrated in an evolving narrative. We first inquire into the introductory segment of the lesson, during which the teacher established the ground rules and demonstrated the technical possibilities of Talkwall. We then shift our attention to how the teacher and the students commenced with their use of Talkwall, including the engagement in blogging activities. Finally, we explore a teacher-led, whole-class activity on the basis of the students’ previous blogging. Together, these three lesson components illustrate how the teacher encouraged and supported his students’ self-expression and reasoning about a sensitive topic by granting them opportunities to apply microblogging in specific ways, which ultimately created an extended space for participation through dialogues.

Ground rules

The teacher began the lesson by giving the students an overview and explaining his intention with the coming activities, including his expectation that the students would talk together. There was a lively atmosphere and chatter amongst the students. The teacher stood in front of the class, while the students were arranged in groups (Fig. 3).

The teacher referred back to previous work when introducing the lesson. He revisited a set of ground rules for discussion that the students developed together. He emphasised three rules: the students should respond to one another, they should build upon one another’s ideas and they should explain and justify their thinking. The teacher then projected Talkwall onto the smartboard to illustrate two technical functions of the tool.

The teacher demonstrated how to build on someone else’s blog contribution on the Talkwall platform, in accordance with the ground rules, and how to move blog contributions from the shared feed to the unique wall of each group. Subsequently, the teacher introduced the topic of the lesson and stated that he wanted to ascertain the students’ opinions about why it is important to learn about the body and sexuality. The introduction ended with the teacher assigning his students a task: ‘Discuss in groups: Why do we need to learn about sex? And blog your ideas to Talkwall as you go’.

Organising blogging with nicknames

Following the introductory segment, the students engaged in group discussions and used blogs to express any ideas that arose. We attended to the premises that were established for this activity and how they played out before we analysed the students’ blog contributions. At this point, the teacher had assigned each group a random nickname for use in Talkwall, which precluded the identification of the group behind any given blog contribution. Notably, in Talkwall, blog contributions become visible to every group on their local computers via a shared feed. This aspect had implications for both the students and the teacher. For the former, blogs did not always have to result from a local group discussion; inspiration might derive from blogs by other groups on the shared feed or even from an emerging and reciprocal interplay between oral discussions and the continuously available blogs. Meanwhile, the teacher could acquire an overview of all groups on Talkwall and observe which groups were active. At some point, the teacher realised that there were too many active groups, some of which bore nicknames that he did not originally create.

The teacher commented on the discrepancy between the number of nicknames that he had assigned and the number of student groups that were blogging. One student started to respond (‘But we have…’) but then stopped himself, and the teacher confirmed his expectation that ‘the number of groups [will] drop to 12’. The students immediately reduced the number of groups on Talkwall, and the teacher did not comment further.

Students’ blogging activities

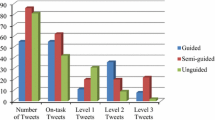

Figure 4 displays an aggregated overview of the general nature and quantity of the students’ blogging activities on Talkwall during this part of the lesson. It quantifies the blogs that each group produced, the instances where they pinned a blog post that originated from their own group and the cases where they pinned a blog post that someone else created.

Interestingly, all of the groups were active on Talkwall, though they published and pinned blogs in varying quantities. Generally, the groups pinned the blogs of other groups more often than their own (25 vs. 55 instances, respectively). The students did not elaborate on each other’s blog contributions on the Talkwall platform.

Our analysis of the students’ blogs reveals that they were generally on task. For a Talkwall contribution to be considered on task, it must attempt to respond to the task, even if it consists of a single word. Figure 5 presents three blog posts that were produced by different groups to offer insight into the scope of variation in how the students expressed themselves in a blog format.

The blogs represent responses from three groups (Puberty 4, Puberty 2 and Puberty 3) to the question posed by the teacher at the beginning of the lesson: ‘Why do we need to learn about sex?’ The blogs differed in length, content, level of precision, use of textual means and voice. The shortest blog is the example on the left, which contains a reference to a process followed by a wink. In isolation, the blog does not state what the ‘process’ entails, but the use of the wink adds a humorous element, and it suggests that the process is closely related to the act of having sex while also illustrating the emotional ladenness of the topic. The blog in the middle is the longest. Its content is more explicit than that of the first blog, and it refers specifically to the importance of preventing sexually transmitted diseases and unwanted pregnancies. The first sentence conveys the serious consequences of disregarding such prevention. The second sentence then stresses the severity of these consequences by connecting them to the personal lives of the students and adopting a serious tone in the remark, ‘that is not fun at the age of 14’. The blog on the right contains only one sentence, which arguably expresses a fear of ‘doing something wrong’ in the sexual act.

Teacher-led, whole-class dialogue

After the group blogging activity, the students’ attention was directed towards the teacher’s smartboard again, where Talkwall was projected. As the previous section has illustrated, the majority of the groups pinned both their own ideas and those of others on their walls.

First, the teacher selected the wall of Puberty 2 and viewed it for a while before reading the blogs out loud (turn 1). A student immediately responded by claiming ownership of the first blog that the teacher read: ‘Hey, that one is ours!’ (turn 2). Laughter erupted (turn 2). While this comment obviously revealed the identity of a particular student who was part of the group Puberty 2—and thus undermined the teacher’s intention to anonymise the groups—the intuitive response from the student (turn 2) could signify that the classroom culture allowed the space to be perceived as safe, and students were not especially concerned about maintaining anonymity.

We observed lengthy pauses between the readings. The teacher continued to read the blogs but occasionally paused before delivering a summative comment: ‘This is almost like, eh (.), the plan for the chapter’ (turn 3). A few seconds later, however, the teacher nuanced this comment by stating that they ‘will be talking about setting boundaries and that stuff’ (turn 3) but ‘won’t be talking so carefully about how the process works, but…’ (turn 3). Thereby, the teacher signalled for the first time that the students should not expect an emphasis on the act of having sex.

The teacher then selected the wall of another group (turn 3). A student noticed that many of the blogs communicated ideas that were similar to those presented on the previous wall (turn 4), and the teacher agreed (turn 5). The teacher resumed his reading of the blogs. The first three blogs contained differently formulated remarks about the act of having sex: ‘We need to learn about it to know which hole to put it in’, ‘then you learn about the human mating dance’ and ‘this is how you know what to do when you are having sex!’ (turn 5). At this point, the teacher reiterated that the act of having sex would not be emphasised. Then, he hesitated: ‘…but eh (..)’ (turn 5). The teacher read yet another blog: ‘So you don’t do the intercourse wrong when you become older’ (turn 5). This blog also directly relates to the act of having sex. The excerpt reflects that the teacher paused several times (see turn 5) and changed his mind. Through the process of reading the students’ blogs, the teacher seemingly realised that students were worried about certain issues, such as a fear of ‘doing something wrong’ to one’s partner. The excerpt closes with the teacher asking the students to elaborate on why it is important to know how to have sex.

The entire sequence of the communication, which includes a dynamic and technologically facilitated interplay between the oral and the written, was generally slow. The concerns and perspectives of the students are evident in many of the blog contributions. The teacher both listened by reading blog contributions out loud and responding to oral dialogues and solicited the students’ thoughts on the topic for exploration. Health, social and moral issues emerged as themes on which the students could follow up in their future work. This additionally constructed a foundation for the students to recognise the potential relevance and value of the teacher’s knowledge and resources on the topic as part of the curriculum.

Discussion

The aim of this research is to analyse the use of microblogging technology by a teacher and his lower secondary students to cope with challenges related to the realisation of student voices in a science lesson involving collective exploration of a sensitive topic. The teacher referenced initial ground rules to clarify his expectations about students’ participation in the activities. He then presented two functions on Talkwall to illustrate action possibilities. Specifically, the groups could express themselves anonymously through blogs, and they could build upon one another’s contributions on the Talkwall platform. The teacher ended the introduction by instructing groups to discuss the importance of learning about sex and to blog their resulting ideas on Talkwall. During the group discussions, the students had the opportunity to express ideas in smaller groups while also having access to the rich array of ideas that emerged from every group in the shared feed.

The aggregated overview reflects the participatory ethos enacted through Talkwall, on which many students expressed ideas and pinned ideas from other student groups—in fact, more frequently than they pinned their own. The students’ blogs were generally on task and varied in content and style. Finally, in the teacher-led, whole-class dialogue, the teacher proceeded systematically through the walls of the student groups and read the contributions out loud. A key characteristic of this last activity was the inclusion of frequent pauses, for which there are multiple plausible explanations. For example, such pauses might be indicative of the teacher reflecting on the blogs. They may also represent the teacher inviting the students to reflect. Furthermore, some degree of hesitation could be involved given the sensitivity of the topic.

This brief empirical summary of the analysis reveals how microblogging was enacted in the first part of the lesson:

-

The students were given the opportunity to blog anonymously.

-

The students had the chance to utilise a function of Talkwall that enabled them to practise a ground rule (i.e. building upon each other’s contributions) on the platform.

-

During group discussions, the students were granted access to the emerging ideas of every other student group via the shared feed.

-

All student groups were active on Talkwall, and the most common action was the pinning of ideas that originated from another group.

-

The students expressed themselves in a blog format, and their blogs varied in length, content, level of precision and use of textual means.

-

The teacher used microblogging to connect learning activities by transferring the outcomes of the group discussions to the whole-class setting. In the full-class segment, the teacher systematically read out blog contributions from his wall and commented on them.

In this context, where a sensitive topic was collectively explored in a science lesson, we must consider how and to what extent the enactment of microblogging afforded extended conditions for the realisation of the students’ voices. With reference to the conceptual lens of Segal and Lefstein (2016), the specific conditions for realising one’s voice can be distilled as follows: being given the opportunity to speak one’s own ideas in one’s own terms and being heeded by others. On this basis, we argue that the analysis uncovers how students acquired extended approaches to participate in dialogues and exercise their voices with the help of mediation by microblogging.

First, every student group was active on Talkwall, which is an interesting finding in itself given that a main aim of the lesson, which the teacher articulated in advance, was to use the tool to remove potential barriers to students expressing themselves while addressing a sensitive topic. It is likely that the teacher’s technique of anonymising participation further reduced the threshold for expressing ideas since, in such a demanding context, social position and communicative repertoire were no longer on display while ideas were being articulated. At the same time, this strategy may have a downside: when ideas are detached from their authors, no specific individual can be made accountable for a particular contribution. In our analysis, this issue might partly explain why some students were tempted to create their own nicknames despite the teacher’s instructions. The teacher’s response was based on the expectations that the students would address the matter respectfully and that sanctions would not be needed. These expectations illustrate a classroom culture wherein the teacher trusts that the students will sort things out themselves. To sustain such a classroom culture, the students were considered responsible for upholding the established ground rules instead of being monitored or reprimanded.

Second, although no student groups actually acted on the teacher’s suggestion to elaborate on one another’s blog contributions on the platform, they did embody the underlying intention of the teacher’s suggestion of remaining oriented towards and connected to the views of other groups by frequently pinning the blog contributions of others. This phenomenon was possible because the shared feed gave every student group access to the richness of the meaning-making of all groups. It implies that an orientation towards otherness manifested through a particular way of utilising the technology. This orientation towards otherness is a precondition for not only dialogic interaction but also the cultivation of an environment in which students are heeded by others (Segal and Lefstein 2016). Students can draw from the richness of voices in a range of ways; they can compare, contrast or support statements by other students, which allows them to position and orient themselves socially and cognitively in the activities both through explicit contributions and in their inner dialogues.

Third, our analysis of the blogs unravels how students can use this particular communication format to convey their perspectives in their own terms and sometimes in ways that are different or even impossible in traditional face-to-face settings. One instance of the latter is the use of a wink in the first blog. Other examples include the connection of undesirable consequences to the personal lives of the students in the second blog and the fear of failing and ‘losing face’ socially in the third blog. The students also expressed a need to know more about ‘how the process works’ and about the social, emotional and relational aspects of sex ‘[s]o you don’t cross your partner’s boundaries during intercourse’. Interestingly, in a recent study in the US that explored students’ opinions of how sex education in schools should be carried out, the researchers called for more elaboration of the social, emotional and relational aspects of sex in classroom discussions. Furthermore, the participants in that study reported that ‘the sex education they received was awkward, not helpful and often used scare tactics’ (Astle, McAllister, Emanuels , Rogers, Toews and Yazedjian 2021, p. 1). In contrast, our analysis evidences that a teacher used the affordance of microblogging in combination with ground rules to realise the students’ voices.

There were also elements of a more ‘official’ voice in the blogs, for instance in the reference to avoiding venereal disease in the second blog. Another interesting finding is that some of these blogs, especially the shorter and less explicit ones, represent ideas that were much more ‘in the making’ than a traditional face-to-face dialogue would allow. The principles of sequentiality, joint construction and act-activity interdependence in this context require speakers to act collectively through mutually coordinated actions and interactions as part of institutional activities that represent a specific form of activity genre (Linell 1998). An idea that is not a direct response to one or more previous utterances will be difficult to situate coherently in a sequence of reasoning. With Talkwall, ideas that were not necessarily fully developed (i.e. were ‘in the making’) could still be expressed and heeded and influence the activity.

The principle of sequentiality, which is a necessary communicative principle for collective meaning-making in face-to-face discussions, brings us to a key finding in our analysis. We argue that the processes described above can be conceptualised as different forms of the communicative principle of sequentiality enabled by variations in technology usage (in this case, microblogging). We contend that these new principles are central to students ultimately being provided a space for participation in discussing a sensitive topic in science wherein conditions for realising their voices are extended. In many classroom studies, artefacts, resources and materials are not considered active parts of interactions. In contrast, our analysis reveals that microblogging produced a new condition for class dialogues and meaning-making.

We discovered this condition, which we term ‘double sequentiality’, by identifying two forms of sequentiality that are not present in classroom discussions without digital technology. The first form emerged on the microblogging platform, whereas the second arose when Talkwall created a triadic structure (Ludvigsen and Steier 2019) in combination with oral dialogues in the teacher-led, whole-class exchange. On the Talkwall platform, ideas could be generated and reciprocally attended and attuned to in multiple ways (read, pinned, moved, revised or elaborated on) without requiring users to adhere to the strict moment-to-moment principle of sequentiality that underlines face-to-face discussions. Therefore, an affordance of Talkwall and digital technologies with a similar design is the ability for ideas to be created and read at any time and for any idea to inspire another at any moment. This altered communicative principle of sequentiality is significantly more flexible in nature compared to that which underlines moment-to-moment or turn-by-turn communication, as the very space of time remains open from the beginning to the end of the blogging activity. However, since the volume of contributions can render interactional situations overly complex, teachers and students will need to devise new forms of coordination and interactional/communicative efforts.

Our examination of the teacher-led, whole-class dialogue also identified a second form of sequentiality when the technology (Talkwall) created a triadic structure in communication dynamics. The term ‘triadic structure’ is inspired by several classical contributions about dialogue as foundational to human development (Habermas 1984; Linell 1998; Schwarz and Baker 2017). The subject-subject-artefact connection creates the triadic structure in which activities are enacted. At the empirical level, the technological mediation enabled an additional layer of voices that is not dependent on turn-by-turn interaction, and both the teacher and the students could bring in and attend to those voices in new ways in their oral interaction. In this particular science lesson, we observed that this seemed to stimulate the teacher’s awareness of some of the worries and concerns of his students regarding the body and sexuality. These ‘voices of the students’ eventually convinced him to change the focus and course of the lesson. The two types of sequentiality are central to ultimately affording students a space for participation through dialogues that extend conditions for realising voices in addressing a sensitive topic in a science lesson. Thus, they enrich dialogues in the classroom. Taking advantage of such opportunities might be beneficial for the creation of opportunities for students to actively participate in science lessons. Students’ voices can enhance the value of activities in science classrooms and facilitate learning through participation.

Final considerations

Some limitations and final implications of this study must be addressed. The topic of the lesson was considered exemplary of a sensitive science topic. Prior to the lesson, the teacher explicitly communicated a concern that social barriers may hinder student participation. However, the students were never explicitly asked about their perceptions of the topic. Our analysis suggests an inclusive classroom culture. However, the assumption of sensitivity was a premise for the interpretation of the data and represents a limitation of the current study. Future studies should address this issue, especially since expectations and norms regarding the body and sexuality continuously transform within a highly complex and dynamic youth culture where young people actively construct their own sexualities (Johansson 2016). In addition, the current work did not explore differences in the students’ experiences of the topic or the implications of such differences for the students’ actions. These considerations should be taken into account in the future work.

Despite its limitations, the present study contributes to the sparse body of research on the actual production of knowledge on the body and sexuality in science classrooms at the interactional level with the support of a specific digital technology to elicit the perspectives and voices of students. In this sense, the work clearly illustrates a possible vision for more comprehensive sex education in science as mediated by microblogging.

References

Aguiar, O. G., Jr. (2016). Explanation, argumentation and dialogic interactions in science classrooms. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 11(4), 869–878. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-015-9694-4

Astle, S., McAllister, P., Emanuels, S., Rogers, J., Toews, M., & Yazedjian, A. (2021). College students’ suggestions for improving sex education in schools beyond ‘blah blah blah condoms and STDs.’ Sex Education: Sexuality Society and Learning, 21(1), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2020.1749044

Bakhtin, M. M., Holquist, M., & Emerson, C. (1981). The dialogic imagination: Four essays. University of Texas Press.

Bakhtin, M. M., Emerson, C., & Holquist, M. (1986). Speech genres and other late essays. University of Texas Press.

Blommaert, J. (2005). Discourse: A critical introduction. Cambridge University Press.

Cohen, J. N., Byers, E. S., Sears, H. A., & Weaver, A. D. (2004). Sexual health education: Attitudes, knowledge, and comfort of teachers in New Brunswick schools. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 13, 1–15.

Cook-Sather, A. (2006). Sound, presence, and power: “Student voice” in educational research and reform. Curriculum Inquiry, 36(4), 359–390. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-873x.2006.00363.x

Cook-Sather, A. (2014). Student voice in teacher development. Oxford University Press.

Furberg, A., & Ludvigsen, S. (2008). Students’ meaning-making of socio-scientific issues in computer mediated settings: Exploring learning through interaction trajectories. International Journal of Science Education, 30(13), 1775–1799. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500690701543617

Gao, F., Luo, T., & Zhang, K. (2012). Tweeting for learning: A critical analysis of research on microblogging in education published in 2008–2011. British Journal of Educational Technology, 43(5), 783–801. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2012.01357.x

Gibson, J. J. (1979). The ecological approach to visual perception. Houghton Mifflin.

Goffman, E. (1981). Forms of talk. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Goldfarb, E. S., & Lieberman, L. D. (2020). Three decades of research: The case for comprehensive sex education. Journal of Adolescent Health, 68(1), 13–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.07.036

Greeno, J. G. (1994). Gibson’s affordances. Psychological Review, 101(2), 336–342. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.101.2.336

Gregory, A., & Ripski, M. B. (2008). Adolescent trust in teachers: Implications for behavior in the high school classroom. School Psychology Review, 37(3), 337–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2008.12087881

Habermas, J. (1984). The theory of communicative action, volume 1: Reason and the rationalization of society. Beacon.

Holdsworth, R. (2000). Schools that create real roles of value for young people. Prospects, 30(3), 349–362. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02754058

Hymes, D. H. (1996). Ethnography, linguistics, narrative inequality: Toward an understanding of voice. Taylor & Francis.

Johansson, T. (2016). The transformation of sexuality. Taylor & Francis.

Jordan, B., & Henderson, A. (1995). Interaction analysis: Foundations and practice. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 4(1), 39–103. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls0401_2

Krebbekx, W. (2018). What else can sex education do? Logics and effects in classroom practices. Sexualities, 22(7–8), 1325–1341. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460718779967

Lefstein, A., & Snell, J. (2014). Better than best practice: Developing teaching and learning through dialogue. Routledge.

Lehmiller, J. J. (2017). The psychology of human sexuality. John Wiley & Sons.

Linell, P. (1998). Approaching dialogue [IMPACT: Studies in language, culture and society, 3]. John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1075/impact.3

Ludvigsen, S., & Arnseth, H. C. (2017). Computer-supported collaborative learning. In E. Duval, M. Sharples, & R. Sutherland (Eds.), Technology enhanced learning (pp. 47–58). Springer International Publishing.

Ludvigsen, S., & Steier, R. (2019). Reflections and looking ahead for CSCL: Digital infrastructures, digital tools, and collaborative learning. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 14(4), 415–423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-019-09312-3

Ludvigsen, K., Ness, I. J., & Timmis, S. (2019). Writing on the wall: How the use of technology can open dialogical spaces in lectures. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 34, 100559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2019.02.007

Lundin, M. (2014). Inviting queer ideas into the science classroom: Studying sexuality education from a queer perspective. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 9, 377–391. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-013-9564-x

Lusk, A. B., & Weinberg, A. S. (1994). Discussing controversial topics in the classroom: Creating a context for learning. Teaching Sociology, 22(4), 301. https://doi.org/10.2307/1318922

Major, L., & Warwick, P. (2019). Affordances for dialogue. In N. Mercer, R. Wegerif, & L. Major (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook of research on dialogic education (pp. 394–410). Routledge.

Manca, S., Grion, V., Armellini, A., & Devecchi, C. (2017). Editorial: Student voice. Listening to students to improve education through digital technologies. British Journal of Educational Technology, 48(5), 1075–1080. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12568

Mercer, N. (2004). Sociocultural discourse analysis: Analysing classroom talk as a social mode of thinking. Journal of Applied Linguistics, 1(2), 137–168. https://doi.org/10.1558/japl.2004.1.2.137

Mercer, N., & Littleton, K. (2007). Dialogue and the development of children’s thinking: A sociocultural approach. Routledge.

Mercer, N., Wegerif, R., & Major, L. (Eds.). (2019). The Routledge international handbook of research on dialogic education. Routledge.

Ministry of Education and Research. (2020). Overordnet del. https://www.udir.no/laring-og-trivsel/lareplanverket/

Mortimer, E. F., & Scott, P. H. (2003). Meaning making in secondary science classrooms. Open University Press.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. (2018). How people learn II: Learners, contexts, and cultures. The National Academies Press.

Oulton, C., Day, V., Dillon, J., & Grace, M. (2004). Controversial issues - teachers’ attitudes and practices in the context of citizenship education. Oxford Review of Education, 30(4), 489–507. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305498042000303973

Rasmussen, I., & Hagen, Å. (2015). Facilitating students’ individual and collective knowledge construction through microblogs. International Journal of Educational Research, 72, 149–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2015.04.014

Richmond, K. P., & Peterson, Z. D. (2020). Perceived sex education and its association with consent attitudes, intentions, and communication. American Journal of Sexuality Education, 15(1), 1–24.

Roth, W.-M. (2009). Dialogism: A Bakhtinian perspective on science language and learning. Sense Publishers.

Schwarz, B. S., & Baker, M. J. (2017). Dialogue, argumentation and education: History, theory, and practice. Cambridge University Press.

Schweiger, S., Oeberst, A., & Cress, U. (2014). Confirmation bias in web-based search: A randomized online study on the effects of expert information and social tags on information search and evaluation. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(3), e94. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3044

Segal, A., & Lefstein, A. (2016). Exuberant, voiceless participation: An unintended consequence of dialogic sensibilities? L1 Educational Studies in Language and Literature, 16, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.17239/l1esll-2016.16.02.06

Silverman, D. (2010). Interpreting qualitative data – a guide to the principles of qualitative research (4th ed.). SAGE Publications Inc.

The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. (2020). Science subject curriculum (NAT1-03). Retrived from https://www.udir.no/lk20/nat01-04/kompetansemaal-og-vurdering/kv78

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2018). International technical guidance on sexuality education: An evidence-informed approach [Revised edition]. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000260770

Wegerif, R. (2013). Dialogic: Education for the internet age. Routledge.

Wertsch, J. V. (1991). Voices of the mind: A sociocultural approach to mediated action. Harvard University Press.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the teachers and students who participated in this study as well as the anonymous reviewers who provided helpful comments on an earlier draft. This work was supported by the Research Council of Norway [FINNUT/Project No: 254761]. The funding source had no involvement in the study design, the collection, analysis or interpretation of data, the writing of the report or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by University Of South-Eastern Norway.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Lead editor: C. El-Hani

Appendices

Appendix 1: Overview of the lesson

Activity | Content |

|---|---|

Whole class | Teacher-led talk: The teacher introduces the topic, reminds his students of the ground rules for the talk and demonstrates technical possibilities with Talkwall. (Excerpts 1 and 2 , Fig. 3) |

Group work | The students are blogging in groups. (Excerpt 3, Figs. 4 and 5) |

Whole class | Teacher-led talk: The teacher reads and comments on the students’ blogs. (Excerpts 4) |

Group work | The students are blogging in groups |

Whole class | Teacher-led talk: The teacher reads and comments on the students’ blogs and then instructs his student to put away Talkwall for a few minutes and search for information about venereal diseases online |

Group work | The students search for information while discussing in groups. The blogging activity is gradually resumed |

Whole class | Teacher-led talk: The teacher reads and comments on the students’ blogs before ending the class |

Appendix 2: Key transcription conventions

-

(.)

Brief pause under one second.

-

(1)

Longer pause (number indicates length to nearest whole second).

-

(())

Description of non-verbal activity.

-

text

Stretched sounds.

-

‘text’

Reading aloud text from the smartboard, sometimes contributions on Talkwall (text and contributions enclosed in brackets)

Appendix 3: Extract from science curriculum

After year 10

-

Formulate assertions and discuss and elaborate on problems related to sexuality, sexual orientation, gender identity, setting limits and respect, sexually transferrable diseases, prevention and abortion

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Frøytlog, J.I.J., Rasmussen, I. & Ludvigsen, S.R. How microblogging affords conditions for realising student voices about the body and sexuality in a science education lesson. Cult Stud of Sci Educ 17, 661–682 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-022-10101-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-022-10101-y