Abstract

Existent research indicates that postsecondary Black faculty members, who are sorely underrepresented in the academy especially in STEM fields, assume essential roles; chief among these roles is diversifying higher education. Their recruitment and retention become more challenging in light of research findings on work life for postsecondary faculty. Research has shown that postsecondary faculty members in general have become increasingly stressed and job satisfaction has declined with dissatisfaction with endeavors and work overload cited as major stressors. In addition to the stresses managed by higher education faculty at large, Black faculty must navigate diversity-related challenges. Illuminating and understanding their experiences can be instrumental in lessening stress and job dissatisfaction, outcomes that facilitate recruitment and retention. This study featured the experiences and perceptions of Black faculty in science education. This study, framed by critical race theory, examines two questions: What characterizes the work life of some Black faculty members who teach, research, and serve in science education? How are race and racism present in the experiences of these postsecondary Black faculty members? A phenomenological approach to the study situates the experiences of the Black participants as valid phenomena worthy of investigation, illuminates their experiences, and seeks to retain the authenticity of their voices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

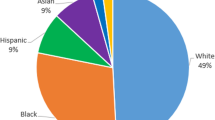

In fall 2013, degree-granting institutions of higher education employed 1.5 million faculty members; Blacks comprised 6 % of the 51 % who had full-time status (Kena et al. 2015). Considering that Blacks made up 4.8 % of all STEM occupations (National Science Foundation 2015), it is reasonable to assume that the percentage of Black faculty in postsecondary STEM was lower than the 6 % of full-time Black faculty in higher education for all fields. Though they are few in number, research documents the essential roles of Black faculty. They value service-related activities like mentoring (Allen-Castellitto and Maillard 2001) and they are instrumental in graduating doctoral students of color (Allen, Epps, Guillory, Suh, and Bonnous-Hammarth 2000). These contributions have increased significance as diversification is deemed a productive venue to address the United States (U.S.) STEM workforce demand, evinced in reports that highlight the shortage of STEM professionals and centrality of STEM fields to economic growth (President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology 2012). Understanding the perceptions and experiences of Black faculty, members of a stigmatized racial group, in postsecondary STEM is important for their recruitment and retention. Because research findings show that perceptions of campus racial climate are strongly correlated with faculty satisfaction, it is necessary to examine race and racism as it pertains to the experiences of Black faculty (Victorino, Nylund-Gibson, and Conley 2013).

This study, with a focus on science education, illuminates the perceptions and experiences of Black faculty by examining from a critical race perspective the following:

-

1.

What characterizes the work life of some Black faculty members who teach, research, and serve in postsecondary science education?

-

2.

How are race and racism present in the experiences of these post-secondary Black faculty members?

In this study, “race is a concept which signifies and symbolizes social conflicts and interests by referring to different types of human bodies” (Omi and Winant 1994, p. 55). Accordingly, racism is defined as a hierarchical superior-inferior relationship among races that is established and maintained by power enacted through social and institutional practices (Bonilla-Silva 1997). The hierarchical superior-inferior relationships are founded on perceived genetically-based differences, visible differences consciously and subconsciously believed to be linked to socially relevant abilities and characteristics (van den Berghe 1967). These differences are considered a legitimate basis for the arrangement and positioning of groups in society (Byng 2013).

Theoretical framing

Critical race theory (CRT) stemmed from critical legal studies (CLS), a coalition of law and law-related professionals committed to exposing and ending the legal legitimization and reproduction of oppression. In the 1980s, a small contingency in CLS questioned the movement’s consideration of race, or lack thereof, in the interpretation and application of law. From this discontent, a movement and a theory with race, racism, and power as their core emerged.

Race-consciousness

Race-consciousness is central to CRT. It is the antithesis of colorblindness, a prevalent approach that ignores and disfavors any use of race. Even though colorblindness is a widespread cultural practice often denoted in statements like “I only see individuals,” scholars highlighted the improbability of its existence. Aleinikoff (1991) and Gotanda (2000) contended that minds are color coded in deep and implicit ways as the result of being immersed in a U.S. cultural context in which race was present and essential in its very founding. “To be truly color blind in this way…requires color consciousness: one must notice race in order to tell oneself not to trigger the usual mental processes that take race into account” (Aleinikoff, p. 1079). Neuroscience research investigating brain activity during racial interactions supports this implausibility of colorblindness (Ito and Bartholow 2009; Richeson, Baird, Gordon, Heatherton, Wyland, Trawalter, and Shelton 2003). Race-consciousness is necessary because of and to address racism.

Racism

In contrast to the liberal view of racism as an isolated, aberrant, irrational, and intentional act of an individual, CRT situates racism as a pervasive, normal and rational structure that functions both with and without conscious intent (Bell 1992). The conscious and subliminal structures of racism work to establish and reproduce racially hierarchical systems. CRT advocates critical contextual and historical analyses of these systems in order to understand how they allocate and safeguard rights and privileges (Crenshaw 2011). CRT challenges the reification of the racial status quo in which the experiences and voices of people of color are often overlooked, distorted, devalued, or dismissed. CRT validates and centralizes the experiential knowledge of people of color and their communities in addressing and eradicating racism and other oppressions (Delgado 1989).

In line with the CRT tenet that racism is pervasive, racism has been the subject of systematic inquiry. Investigations have shown that racism functions at different levels and materializes in various forms. Institutional racism, personally mediated racism, internalized racism, and racial micro aggressions are a few manifestations that occur at macro (e.g., society) and micro (e.g., individual) levels.

Institutional racism, operating largely at macro levels (e.g., societies, organization), is defined as differential access by race to society’s commodities. These commodities include but are not limited to goods, opportunities, material conditions, and services (Jones 2000). A differentiation in power undergirds this differential access. Institutional racism is often embedded in formal and informal codes, policies, practices, et cetera; consequently, it assumes a life of its own and a sole culprit for its existence is often unidentifiable. In contrast, an identifiable perpetrator exists for personally mediated and internalized racism.

Personally mediated racism, functioning at micro levels (e.g., interpersonal interactions), is racism most commonly referenced in the public domain (Jones 2000). Prejudice (i.e., differentiated assumptions about others that are based on race) and discrimination (i.e., differentiated action towards others according to race) constitute this form of racism. Personally mediated racism can include what one does (e.g., actions) and what one does not do (e.g., complicity). It can be intentional and unintentional and enacted with or without awareness. Another manifestation, also operating at a micro level, is internalized racism (Jones 2000). In this form of racism, racism is turned inward. Members of stigmatized groups accept the negative valuation and evaluation of their group and act accordingly. Other enactments of racism are captured in racial micro aggressions.

Racial micro aggressions are commonplace, brief encounters that communicate derogatory messages to the intended individual (Solorzano, Ceja, and Yosso 2000). Racial denigrations intended to inflict harm are called micro assaults; they usually take the form of verbal and non-verbal attacks (Sue, Capadilupo, Torino, Bucceri, Holder, Nadal and Esquilin 2007). The most blatant micro assault is the use of a racial slur or epithet. Micro insults are subtler than micro assaults; they demean a person’s heritage or identity (Sue et al. 2007). A prevalent micro insult is the treatment of past oppressions (e.g., slavery, segregation, legalized exploitation of immigrants in the agricultural industry) that have indelibly impacted generations (past, present, and future) as inconsequential to what currently exists. Although micro insults can be intentional, they are often inflicted without the perpetrator’s conscious awareness. Micro invalidations can be viewed as an extension of micro insults. These racial micro aggressions “exclude, negate, or nullify the psychological thoughts, feelings, or experiential reality of a person of color” (Sue et al., p. 274). The pervasive statement “I don’t see color” in the U.S. to people of color for whom race is salient is an example of a micro invalidation. “I don’t see color” essentially indicates to individuals for whom race is salient that an important aspect of their identities is irrelevant or unimportant.

Framing of the study

In this study, CRT is not used to inform the analysis; that is, its elements are not employed as coding schemes from which to view the data. Instead, CRT provides the underlying assumptions that influence the focus of the study, the undergirding premises which shape how the study was conducted, and a lens for understanding the study’s findings. CRT is reflected in the assumption that racism is present in the experiences of Black faculty in postsecondary science education: how rather than if racism operates is the emphasis. In accordance with CRT’s centering the experiential knowledge of people of color, this study situates the experiences of the Black participants as valid phenomena worthy of investigation. The investigative approach, a phenomenological study, illuminates their experiences and seeks to retain the authenticity of their voices. Although the research on postsecondary faculty in general are summarized for the purposes of positioning this study in the existent research, in this study the experiences of White faculty, those highlighted in the literature due to their overrepresentation in academe, are not used as the norm for validating or authenticating the experiences and voices of Black faculty. Additionally, the synthesis of research on postsecondary faculty in general further illuminates the additional complexities experienced by Black faculty. That is, current literature shows that the experiences of Black faculty include what characterizes the experiences of White faculty who are overrepresented in the academy and other complexities not experienced by White faculty. The experiences of Black faculty in postsecondary science education are complicated by the historical and contemporary positioning of their racial group globally (Mutegi 2011) and in the U.S. as the “inferior other” (Parsons 2008).

Faculty and Black faculty work life in higher education

Research since the 1980s, when research on postsecondary faculty emerged (Johnsrud 2002), has indicated that faculty members have become increasingly stressed and job satisfaction has declined (Schuster and Finkelstein 2006). Research has shown that dissatisfaction with endeavors and work overload are major stressors (Jacobs and Winslow 2004). Research also has indicated that constraints on time, considered a scarce resource by faculty, have lessened work life quality (Russell 2010) and that administrative duties have been among the most time-consuming and the work least favored by faculty (Rosser 2004). In addition to the previously mentioned, other factors have attributed to job dissatisfaction. Climates that have inadequate resources which are inequitably distributed; are unsupportive and unappreciative of faculty efforts; have limited faculty autonomy, intellectual stimulation and opportunities for professional growth; and lack collegiality have contributed to the decline in faculty members’ satisfaction with their jobs (Olsen, Maple and Stage 1995).

Black faculty members have experienced the stresses managed by faculty in higher education at large and, according to research, Black faculty must also navigate diversity-related challenges. For example, Black faculty have more readily accepted requests to provide diversity-related services (Griffin, Pifer, Humphrey, and Hazelwood 2011), which exacerbates stresses associated with work overload and time. These stressors have been intensified by the pressures to justify one’s productivity because diversity-related service has not been valued in reappointment, tenure, and promotion decisions (Diggs, Garrison-Wade, Estrada, and Galindo 2009), an example of micro invalidation, a racial micro aggression. Just as the stressors of work overload and time were complicated by pressures pertaining to involvement in diversity-related initiatives, there are other dimensions of work climate not typically experienced by White faculty, the majority in higher education, but are managed by Black faculty.

Inadequate resources that are inequitably distributed, organizational cultures that are non-collegial, and work climates that are unsupportive and unappreciative of faculty work are augmented for Black faculty by race-related tensions in teaching. Research has shown that students have unjustifiably evaluated Black faculty members poorly in their teaching, especially in race- and culture-related courses (Smith 2007). Additionally, the colleagues and administrative leaders of Black faculty have accepted without question the students’ valuations (Smith and Hawkins 2011). These challenges to Black faculty members’ professional competencies are not limited to the classroom. The discounting of research agendas involving people of color; disparaging of non-mainstream research techniques; and marginalization and exclusion from capital-sharing and capital-producing activities like mentoring by and collaborations with colleagues have also been documented in research on Black faculty (Stanley 2006). Black faculty members, the population of interest in this study, have experienced both the typical stressors associated with teaching, research, and service in postsecondary institutions and unique challenges related to being a member of a stigmatized racial group.

The investigation

The featured study was conducted within the phenomenological research tradition that includes diverse approaches. Phenomenology, in general, is the examination of lived experiences as they are structured through consciousness (Frieson, Henriksson, and Saevi 2012). This study’s approach most closely aligned with interpretive phenomenology in which the individuals’ subjective experiences are emphasized (Bogdan and Biklen 2003) and researchers contemplate the meaning of those experiences (Van der Mescht 2004). In this instance, the researchers were Black faculty members who have experienced the phenomenon of interest and for whom the topic has personal and social significance (Gall, Gall, and Borg 2007).

The study presented in this article was based on a data set for a larger investigation involving 18 participants (see Atwater, Butler, Freeman, and Parsons (2013) for a description of the larger study). A subset of data from a larger inquiry was subjected to analyses guided by purposes that differed from the study from which the data originated. In contrast to the centrality of race and racism in this study, the purpose of the larger study was a general understanding of the successes and failures of Black faculty in postsecondary science education.

Four participants from the larger study were purposefully selected for this study. All participants were classified as Black according to the U.S. census categories, but the participants indicated different ethnicities. In order to protect the anonymity of the research participants in the small science education community the specific ethnic identifiers, except for African American which is a group with greater representation in science education than Blacks of other ethnicities, are not provided. The goal to maximize variation on several dimensions guided participant selection (Patton 2002): Gender (two males, two females), ethnicity (two African Americans and two Blacks who identified other ethnicities), location of institution (South and Northeast U.S), years in faculty position (two with 2 years, one with 8 years, and one with 17 years), and rank (two untenured assistant and two tenured associate professors). The type of employing institution was also considered as part of the selection by using the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching (2015) classification.

Two study participants worked at a master’s institution. Master’s colleges and universities are institutions that awarded at least 50 master’s degrees but fewer than 20 doctorates. Institutions classified as very high research activity employed the other two participants. Classification of institutions as very high research activity is determined by research expenditures, number of research doctorates awarded, and number of research-focused faculty. Two of the participants worked at an institution with about 8 % of the faculty population classified as Black, less than 1 % at the rank of professor, less than 1 % at the rank of associate professor, and approximately 7 % at the rank of assistant professor. The two remaining participants were employed at an institution that reported its faculty composition as 5 % Black, without rank demarcations provided. The student enrollment at the research institution for which research was the primary mission is almost five times as large as the Master’s institution, with Black students constituting a little less than 10 % at the large, very high research institution and a little less than 30 % at the smaller, Master’s one. The institutions expected each research participant to teach, research, and serve.

Data sources and analyses

The larger study employed multiple data sources in order to enhance the accuracy of the researchers’ data interpretations (Guba and Lincoln 1989); two sources of data—demographic survey and two semi-structured interviews—were analyzed for this article (see Atwater, Butler, Freeman, and Parsons 2013 for details about the survey and interviews). Two semi-structured interviews, the major source of data from the larger study analyzed for this study, consisted of questions regarding the participants’ responsibilities in, perceptions about, and personal aspirations for the academy; their interpretations of the institution’s expectations and their assessments and challenges in meeting them; and the participants’ views of self with respect to the customary domains of teaching, research, and service.

Researchers entered the verbatim transcriptions of the semi-structured interviews into Atlas.ti, a software program that facilitates data coding. The researchers developed textural descriptions that accounted for the individual’s perceptions and structural descriptions that captured regularities across the four participants (Gall, Gall, and Borg 2007). Researchers made the process of developing structural descriptions more systematic by employing coding strategies in qualitative research (Miles 2014).

Researchers subjected the interview data for each participant to inductive coding. Texts from the individual interviews were segmented into units that contained one major idea in order to succinctly answer “what is this text about.” Researchers merged the resulting codes that had similar meanings; this merging resulted in tentative thematic labels. Researchers then examined the codes, products from the inductive coding process, across the interviews and articulated the meanings represented by the codes into characteristic themes. Lastly, the researchers subjected the interview data to deductive coding. The deductive coding, codes derived from the literature, was primarily conducted to uncover as many meanings as possible from the data and to more thoroughly compare the participants’ experiences to what is featured in the existing research. To substantiate that the meaning captured in the codes and themes were rooted in the data (Guba and Lincoln 1989), the researchers searched for contradicting evidence in the interview data, used the words of the participants in the reporting, and conducted an external review.

Four second-year PhD students and two faculty members were asked to match selected exemplar quotations to the descriptions of the developed themes and to offer any comments regarding their matches. Two Blacks, one reared outside the U.S., one Indian, and three Whites completed a matching exercise that featured three items for each of the five initially identified themes. The percentage frequency of agreement of the external reviewers’ matching with the researchers’ interpretations was calculated for each item and averaged for each theme. The averaged frequency of agreement for each theme ranged from 56 to 83 %. The external reviewers overwhelmingly interchanged two identified themes; that is, the reviewers matched items cited by the researchers as evidence of one theme with another theme. The comments provided by the external reviewers (e.g., “both A and E work”) resulted in subsuming one theme into another, thereby reducing the number of themes that existed across the participants.

Findings

What constituted the work life of Black faculty members who teach, research, and serve in postsecondary science education and how race and racism were present in their experiences comprised this study’s objectives. The findings, in response to the first objective, showed Black faculty experiences were similar to those of postsecondary faculty in general. In addition to the experiences common to faculty in higher education, the findings featured another dimension, often neglected by the dominant group in the academy, which pertained to the second objective. The second set of findings indicated distinct racial experiences for Black faculty, a complexity that is absent for faculty whose racial group has not been positioned historically and contemporarily as inferior in national (e.g., U.S.) and global contexts (Mutegi 2011; Parsons 2008).

The findings are presented in three parts. The results from the textural analyses that conveyed how each participant characterized their experiences are presented in the first section. In order to retain the authenticity of the participants’ voices, one approach to clearly convey subjectivity of phenomenological studies, language used by the participants primarily constitutes the textural findings. The structural analyses, aligning with the aspect of interpretive phenomenology that enables researchers to contemplate meanings of the participants’ expressed experiences, highlight themes across the participants. The results of the structural analyses are presented in the second section. The last section unpacks the findings with respect to race consciousness and racism, the core of the second research question.

Section I textural results: participants’ subjective experiences and perspectives

The experiences described and the sentiments expressed by the participants likely resonate with the vast majority of post-secondary faculty. Each participant, regardless of rank, institution type, ethnicity, and gender, described the myriad of responsibilities and expectations required of faculty. They implicated the varied stresses and tensions higher education faculty in general manage. The participants’ words illuminate the unique imprint of these responsibilities, expectations, stressors and tensions in their respective professional lives.

Dan

Dan is a Black male who did not self-identify as African American. He was born and reared outside the U.S. At the time of the study, he was a tenured associate professor at a very high research institution. He described his current job responsibilities as follows:

[At present, my responsibilities are] more administrative than I’d like – I am a program coordinator. So I supervise all of our undergraduate programs, all of our MA programs and all of our M.Ed. programs in science ed. More than I would like… I still teach the regular secondary science methods classes, for undergraduate and graduate. From time to time, less than I would like, I still teach the occasional introductory chemistry class over in our chemistry department. I don’t want to leave the content. And, again from time to time, I teach … action research course.

Dan’s job responsibilities were replete with tensions. One tension pertained to the contradictions among his and the institution’s expectations.

If I was doing what I know the university rewards and I spend all of my time, or the bulk of my time, publishing. I actually like to write which would work. However, I actually also like to teach. … I spend…a lot of time, preparing my class materials.… Usually when I teach my undergraduate methods classes… almost every semester, one of my undergraduate students will say to me, ‘I didn’t expect to learn this much in this class.’ And then I have to know: what did you expect to learn – nothing? Last week one of my former undergraduate students…she’s now graduated and been teaching for three years – sent me an email [that] said, ‘Just wanted to thank you for all the things you made us do and you made sure we understood this stuff in class, because now I’m doing it in my classroom and it’s working great and I received teacher of the year.’ So it’s successful in that respect. It’s not successful in the sense of I cannot rely on that if I wish to make full professor. It won’t happen. When I think of service, the university definition of service to me is that committee work which I do because I have to. I can’t say I enjoy it tremendously…. For me service is if I’m asked to … do a presentation to teachers or students just on chemistry or biology.…. There’s a sense of personal fulfillment or gratification that others are benefiting. I’m able to do something or say something or just help people understand concepts. Again, that in itself, however well it’s done, won’t advance me professionally.

The misalignments among Dan’s and the institution’s expectations and demands were exacerbated by the lack of time.

… lack of time [is the first challenge]. Being able to focus adequately on things that I want to accomplish and now have the opportunity to accomplish …. I haven’t been able to do that in any satisfactory way at this point. After 12 years of being a professor and now tenured and all the rest of it, I still find it difficult to balance work and family. …before I was tenured…I was on campus, in my office, at work, every day…or with colleagues, …I would say about sixteen, seventeen, eighteen hours a day. Seven days a week – weekends included.

In spite of the tensions and challenges, Dan was tenured at his institution but, he did not feel he was reaching his fullest potential. Dan struggled to satisfactorily realize his own aspirations.

No, [I am not functioning at my fullest potential in the academy]. … we are understaffed. And …it wouldn’t be an exaggeration for me to say I am now doing essentially two people’s jobs…. Basically … that leaves me less time to develop myself professionally… Research for me right now is … trying to build a base foundation for this new field….Work on my journal that I’m the editor for and get that off the ground… My vision … is to become a top scholar in my field. The realities of day-to-day paperwork, advising, teaching – which are good – but they take away from that vision.

Dan conveyed the stress of mediating the contradictions and summarized his approach to managing them in his advice to a newcomer to academe.

Make sure this is something you really want to do. Reason I say that is, yes it can be very fulfilling, yes it can be very exciting, yes you can feel as if you are making a difference, yes. At the same time it can be extremely draining, it can take a huge toll on you. … Second thing…be the best or try to be the best at whatever it is you do….you have to in order to survive in this particular environment. Third, … make sure you know what the rules are. And many of the rules are not written….there are unwritten rules that I had to stumble to figure them out as I went along. Make sure you know what the rules are. …or the expectations and go beyond the expectations. Maybe this might be a bit controversial…. I acknowledge the importance of the whole “opening science education and making sure we devote time and resources to making…enhancing African American and minority participation” – that’s necessary…I think that’s still seen as being on the fringes as some type of insular group of people pursuing kind of what’s outside the pail. I think that type of work still needs to be done, but I also think that we or Black science ed. researchers need to at the same time become more fully involved in some of the primary types of research – start working more with engineers and physicists and biologists … – I see no Black people, whatsoever… there was a education seminar … there were maybe 100 people…. I counted 2 Black people, and I was one of the two and the other was a doctoral student.…I’d like to see more science ed. researchers looking like us in those types of fields because we have a very marginal involvement in that right now…If we can marry some of what we currently do here to some of that, then I think we could make a much greater impact.

Damon

Damon is a Black male who described his ethnicity as African American. He was an untenured assistant professor at a Master’s institution. Damon had been in the academy for two years as an assistant professor. As an assistant professor, he devoted most of his time to program administration and advocacy.

My responsibilities are overwhelming at times… I feel that I’m almost a full-time administrator. I feel that the administrative duties are just unfairly too too too much to tackle. … as a faculty of color I find now that I’m attracting a lot of the students of color who need advocacy…. So what happened is that the word got around that if you want a fair share, reasonable, someone who understands the situation that you seek [Damon] out..I ended up coordinating the traditional program…and…an … alternate certificate program…. Then I grew the other program… because … [it] reflected the diversity of [community] and abroad so those are the type of teachers I felt that we needed to bring in more and needed more attention because the [other] program was saturated with…, about maybe 100 of them [and] 90 % [were] white European…. So now … you’re training teachers now in [community] where …, let’s say 85 % of them are not even indigenous to urban environments…. So, I felt that it was important to make sure …our local alternate certificate program and our traditional students needed to be represented. A contingent of them came to me, the traditional students and our home grown alternate certificate program [and] said ‘… We need advocacy.’

Damon also included teaching among his job responsibilities, an area where he perceived he faced race- related challenges.

Anytime I taught traditional students and our home grown programs I got very high teaching ratings…. like, 3.6 out of 4, 3.7 out of 4. But when I taught the class of only the [students external to community] it plummeted down to 2.8 and I was reprimanded for that. Yeah, they wrote that up in my annual review. … someone pulled me aside and …said, ‘You know what, it turns out it’s not necessarily … that I was a Black professor’ although a lot of it was that. They said that the [external students] don’t respect the college and no matter, it turned out no matter who the professors were, they were always getting lower ratings, but the Black professors got the lowest from that population.

Challenges also existed in other domains such as the assignments he received or did not receive in his department.

When I came on board… they were very interested in doing e-portfolios. And they were looking for someone to do e-portfolios. Now that’s what I’ve been doing at [institution] very successfully and driving that. And …I was… left out. And the person who they asked came to me and said ‘I need help because you’re the one who’s been telling me how to construct all of this stuff for e-portfolios. Why don’t you come on board?’ but … I was marginalized out of it. … So I helped in the background.

In addition, Damon described tensions that he experienced as a Black male.

… having to…prove myself more than … other colleagues who come in at the same time with the same credentials. What contributes to it is ‘cause I’m a Black male… I would say that …the division of education had some real problems a couple of years ago, in terms of being diverse. ….So for myself coming on it was a double plus for them, being Black and being male in terms of a city where you have about 50 % Black male unemployment. However, I find that when it’s time to go meet a corporate sponsor, it’s not me. It’s someone who has the typical corporate demeanor, who is a professor also. I’m talking about all us being … on the same level. We’re all science educators …assistant professors. We all came in at the same time.

In spite of the marginalization and associated tensions that he attributed to race in concert with the traditional stresses associated with faculty responsibilities, Damon made notable contributions. He brought “a sense of research into the science education program,” built the alternative certificate program that reflected the community population, and strengthened the traditional program. Even though Damon recognized the ways in which he had contributed, Damon believed his growth had been impeded. He was not fulfilling his potential in research, the domain that constituted his core professional identity.

Well, I thought that I would be certainly doing much more scholarly research or have more time to do scholarly research … But it’s just been overwhelming to be an administrator. … time, just … time to work on my writing and my research … I would say no, [believe that I am working to my fullest potential]. I think I would probably need a much lower administrative role and a much lower teaching role for the next two years.

I’m a science education researcher, but … pragmatically…—am I an administrator or am I a researcher? … definitely for me my core identity is rooted as a science education researcher, so that even if I decide to leave the academy… no one could tell me that I’m not a science education researcher. … I do not need to be a part of a university to really construct my identity. I can still write and publish even if I’m driving a bus.

Danielle

Danielle, a Black female who did not ethnically self-identify as African American, is an untenured assistant professor at the Master’s institution where she had been employed for two years. The job responsibilities she described were administration, research, and teaching.

I’m … working with … colleagues to kind of build the science education program … So there is a lot of program coordination responsibilities, and of course teaching responsibilities, and then research. … I like the teaching and the research aspects of my work and find the administrative part, …very time-consuming. … they’re very important; but… you have to be careful as to how you end up dividing up your time. You have to teach, but the research is extremely important as well. I really like the research because the research I’ve done in the past always aligned with working with my students. … I definitely enjoy that a lot…they’re all graduate classes that I teach so [institution] has a requirement of students doing…a research project, so what I do is teach, it’s a one-year course, so I teach the first class…. And then the second half of the year I teach another class that’s connected to the research in that…. I also teach this historical foundation course in science and science education…. and I also co-teach … a methods class for…new students coming in, but they are all graduate students. … They have a science background, they’re doing an alternate route certification…

She found it necessary to explicitly address race in her teaching and applications of her research.

And often times,… people coming from other parts of the country they have a certain view – we all have our certain views as to who people are. Unfortunately kids of color – they often get labeled, inscribed, in not the most positive of ways. And, so, having an opportunity for discussions around that, and being a Black person and…kind of confronting people and saying: …you don’t know what the situation is so you cannot talk about students in that way; why do you feel that way and have you thought about this…; and how can we work on really engaging students in science versus saying all my students, they never do homework, they don’t want to, they just break things in the classroom…. And, so, … challenging that because I think it’s easy, especially with certain groups of students, to kind of gain solidarity in the negative.

In addition to working with teachers as part of her teaching and research, she worked with students.

[As service], there’s this group of undergraduate students who…have been just recruited into the school to do a degree in math and science and become math and science teachers …. They’re from the community, and taking them on and mentoring them and, I think, having a conversation with them, checking in with them…. I think that’s very rewarding having that connection with those young students.

Overall, Danielle enjoyed many of her job responsibilities but she expressed a void and feelings of being circumscribed and constrained.

I kinda feel like there would have been more by this point…. I have a lot work – don’t get me wrong, but…I feel like you can really get bogged down with the administrative stuff and so you could get removed from your research, your writing…really staying engaged in the content.… I also have … colleagues … who are very, very good colleagues to work with. But I just… feel… like something’s missing. I’m not quite sure what it is.

… being a Black female in the academy is definitely an interesting walk to walk…I think wearing this flesh, if you will, … throughout life you kind of … go with your gut, your instinct a lot…You can be inscribed in a certain way – positively or negatively. …I feel as though I’m being inscribed in a certain way …I don’t feel readily included in the picture. I think that there’s a lot of deferment to another colleague who is kind of very corporate looking and different ethnically than me. But of course being inscribed also by students who… are very different [from] me….. different not only around race and ethnicity but around just having different experience as far as living experience, involvement with certain populations of people.…I think there’s some testing of the students.… I really wanna, I don’t know if it’s going to happen, but I really wanna feel like myself in the place that I’m working. Once you feel that you’ve been accepted for who you are…I think you can be more productive.

Unsurprisingly, Danielle did not think she was reaching to her potential.

No, not at all because I feel like my creativity is stifled and once I feel a little more…free to explore, to do what I like to do, what I’m good at. I think right now I’m feeling a little… restrained…[To function at my best] I think, having the ability to have more good conversation without fear of repercussions…. Having…developing relationships with people that are sincere.

Dee

Dee is a Black female who self-identified as African American. She was an associate professor at the institution for which research was primary, her very first job in academe. She won a large prestigious grant, which secured her release time from teaching. She described her job responsibilities as “mostly research, then teaching (because I teach one course), and of course service.” Dee did not provide specifics in characterizing her job responsibilities but detailed her challenges.

My very first year was a very rocky year at first. I had extremely poor evaluations. I was asking them [students] to write coherent paragraphs on different assignments, and they told me it was not a writing class it was a science class. The other thing they resented was I tried to bring in a cultural understanding piece, and they tore up my evaluations saying ‘she’s trying to make us learn this culturally relevant stuff, this is … science methods courses.’ And what I did was I tried to bring in some of Geneva Gay’s stuff, some of Delpit’s stuff, … So I wanted them to understand the cultural issues that they could probably face in an urban school, and I had them actually read one piece by McIntosh that… they called me racist. I said well this is a little White lady that wrote this; I didn’t write it, an African American didn’t write it – she’s a White lady saying this. So I just gave up after two years because my evaluations were horrible.… And I got called to the carpet, and I had to go in and sit with my chair, and we had a face-to-face about my evaluations. Wasn’t nothing pretty…After I met with the chair, he came in and observed me again, and actually said ….he thought my classroom culture was just fine….we have what’s called the faculty development center, I had them come in and give me some tips, and I went to a couple of workshops. So I tried to show that I was doing all the things they thought I should be doing, at least making some attempt to improve my teaching. But I understood the two main things I did was to not even ask them to write and not talk about culture. That really turned it around, but I still did the outward things. … So I included all that kind of data when I submitted my annual evaluation. From that point on I started getting excellent, excellent, excellent. [The] only thing I did different from my perspective was to not ask the students to do two of the things I really felt they needed to know how to do. I just didn’t do it, after two years of trying to get them to see…trying to get them to understand that teachers write…and you won’t teach all White kids. It wasn’t going anywhere, so my husband said, ‘Turn the evaluations around, I mean, if you don’t do it you won’t get tenure.’ So, to be honest I had to go against my own beliefs in terms of being at least an acceptable writer and the importance of having students understand the importance of their cultural beliefs and how it impacts how they teach. I did not do those things the next two years. Evaluations turned around. [The first two years] the only thing that wasn’t poor was my research. I had complete control over that – the only one where I did not have a poor rating. Service they don’t count as much, it was okay…They didn’t think I did enough service in schools, but they had me on all these committees, and then they wanted me to write so I’m saying, ‘How can I be in the schools all the time if I have to learn how to teach these courses and do it well, get publications out.’ So that was the mix at the very beginning. Again, trying to balance all three and do it the way they wanted me…The other one was adjusting to a predominantly White institution where I had little support, very little support. It really was not only publish or perish, but it was also sink or swim. People were kind in terms of speaking to you, asking how you’re doing, but didn’t really give you any help to make sure you were doing it right….I really didn’t have any support that maybe some people would get…

After the conferral of tenure, Dee channeled her energy differently, from survival to excelling. Nonetheless, a plethora of challenges awaited her; some reminiscent of those early in her career and others completely novel.

Now that I’ve made associate…the shift is more toward research but I think it is more my choosing than it being imposed upon me because I’m in [name of] department and for the most part many of my colleagues have been …content with teaching….[research expectation] may be more self-imposed. The first pressing challenge for me is time management as it relates to me getting my publications out. … we’ve gone into so many different meetings that you don’t get any real credit for – it takes up a lot of my time that I could be using for my research – so trying to manage my time so that I can focus on publications. The second challenge for me is building relationships with the college of sciences. For us, … some members of the college of sciences don’t really see the value in science education, and the grants I want to write I [am] expected to have their input. So I’m challenged now with trying to build relationships….And the third challenge as it relates to the academy is… promotion.… I am trying to put in the work I need so I can move to the next level….I didn’t intend to get promoted and just stay there. I want to keep going.

Despite the challenges, Dee made significant contributions in teaching, service, and research.

In terms of teaching, I’ve actually developed a Ph.D. in science education track almost by myself. I had some input from others, but it was mine to do.. … of course, now I’m doing the majority of the teaching in the program. … In terms of service, I’m very involved with the [organization], and I was the elected [office], and my goal was to get urban science education to become a part of the…structure of how they operate and address student needs in urban settings. I was able to get a motion through the board that this year the person who was my follow-up…actually got approved. So we now have an urban science leader group…and I am the first appointed or selected chair for the group. Research, I’m the first at my university to actually get a [large prestigious grant] in the college of education. Most professors at the [institution] who have [grant] are in the college of sciences. So I was able to write a proposal that the research was deemed important enough and that it was well-written enough that it was funded for five years…. That to me was an accomplishment. No one else in my college has done that.

Even with her laudable achievements, Dee believed she was doing well but not her best and she aspired to greater accomplishments.

I feel that I’m functioning very well but not at my best. And probably not at my best right now because of…[loved one] going through a rough time right now. So she consumes a good bit of my time because I don’t want to put her in a nursing home – that’s not going to happen. …So – no, I am not at my best, but I’m not a slacker – I am fulfilling all of my job’s expectations. I don’t go in and complain. In fact, most of the people I work with don’t even know I have [a loved one] who is in the condition that she’s in because I don’t think I need to hold it up to them as if ‘now you need to pity me, I have an excuse for why I don’t do….’ I still take care of my job….Hopefully I can get substantial publications out there, get a little bit more recognition for myself. I would like to go for professor…for sure.

Dee’s work did not end with her own achievements and development. She was aware that her plight was not unique. “I had a faculty person who was in higher education. She gave me several articles to read that talked about African Americans in the academy. So I found out that I wasn’t the only one with these challenges.” Consequently, Dee offered her help to faculty from other diverse cultures.

Well since I’ve been at [institution] we’ve probably had maybe four African American professionals to come after me and of the four, only one before, only one has stayed…. I would like to see more people of diverse cultures in the academy. I think in order for that to happen it is important for those of us who are successful to really be interested in the development of others… I try to reach out to everyone who comes to the university, who’s diverse especially, and let them know that if there’s anything I can do to help them just let me know. I even tell them some things they need to know in terms of culture – some little dos and don’ts, when you need to keep your mouth closed. I mean, things that are not written in the book but can make the difference between you staying and going. So it’s important for those of us who have had any level of success to reach back and do what we can to help someone else, and that’s the only way it’s gonna happen.

Section II structural results: researchers’ sense-making of participants’ experiences

In the preceding section, the participants’ own words featured the subjective experiences of the Black faculty members, portraying the subtle uniqueness of their encounters. For example, each described their teaching but situated it differently. Dan accentuated his success despite students’ expectations to receive little from his teaching. Damon and Dee foregrounded challenges related to poor student evaluations, and Danielle centered teaching as a platform to disrupt what she called “solidarity in the negative” around children of color. The researchers’ sense-making of the expressed experiences, the focus of the structural analyses, purposefully looked for commonalities across the study participants. This examination across participants revealed certain domains in which the participants’ experiences converged. These convergences were represented in four themes: job characterization, time, research centrality, and student othering.

Theme 1: Job characterization

In characterizing their jobs, they described their responsibilities and how they experienced them. As indicated in the textural findings section, the participants included teaching, research, and service among the characterizations. They discussed what they were expected to do, what they did, and what they wanted to do. They also described and commented on self-assessments and others’ evaluations of their performances. Notable differences existed in their encounters as featured in the textural results, but convergence across the participants in their job characterizations occurred in two areas: assisting others and administrative work.

Assisting others as part of their job characterization was the first commonality. Dan implicated the focus on others in the time he devoted to his teaching and his aspiration to provide service that benefitted others in lieu of service customarily defined in the academy as obligatory committee work. Damon prioritized helping others in his advocacy for students of color who sought him out because of his reputation: “if you want a fair share, reasonable, and someone who understands the situation that you seek [Damon] out.” Similarly, Danielle aided undergraduate students who had been recruited by the employing institution from the surrounding local communities to pursue math and science degrees. Unlike Dan, Damon, and Danielle, Dee helped a different population; she directed her energies to support colleagues of color.

Administration was the second domain in which the Black faculty members’ experiences converged. All the participants engaged administrative work. Dan supervised all the unit’s undergraduate, MA, and M. Ed programs in science education. Damon and Danielle, both untenured and in their second year in the academy, were responsible for building the employing institution’s science education program; and Dee developed and implemented the unit’s PhD in science education program. How these administrative duties were experienced by the participants was poignant in the second and third themes that emerged across the encounters shared by the participants.

Theme 2: Time

The participants’ framing of time differed little from what has been presented in the literature on faculty in higher education. The responsibilities of faculty are numerous with seemingly not enough time to manage a myriad of expectations. Each participant described some form of administrative or managerial responsibility as part of their jobs and they lamented about its toll on their time. Dan spoke of working 16, 17, 18 hours a day seven days a week and balancing work and family, a feat he had not yet attained after 12 years of being a professor and after being tenured. Damon shared sentiments of being overwhelmed, Danielle expressed the caution of being “careful as to how you end up dividing up your time,” and Dee provided a pre- and post-tenure perspective with time consistently being a challenge to “getting…publications out.” The participants viewed the lack of time, exacerbated by the administrative responsibilities, as a deterrent in engaging tasks they considered valuable and as an impediment in their desired development. What the participants desired for themselves is core to the third theme.

Theme 3: Research centrality

Each participant expressed that they were not realizing their potential and the realities they experienced greatly differed from what they expected. This gap between reality and expectation and functioning below their potential revolved around research. Research centrality, the third theme, denotes the value and significance of research to the participants. The desire to do research was expressed by all the participants: Dan aspired to be a top scholar in his field, Damon and Danielle desired to do research because they enjoyed it, and Dee wanted to “get substantial publications out” so she could be promoted to professor. The significance of this desire to conduct research and the conflicts that ensued, professional identity stresses in this instance, were best illustrated in Damon’s comments:

I’m a science education researcher, but … pragmatically…—am I an administrator or am I a researcher? … definitely for me my core identity is rooted as a science education researcher, so that even if I decide to leave the academy… no one could tell me that I’m not a science education researcher. … I do not need to be a part of a university to really construct my identity. I can still write and publish even if I’m driving a bus.

Conflicts and tensions were not limited to the participants’ desires to do research, but also existed in the interfaces with students, the focus of the fourth theme.

Theme 4: Student othering

Brons (2015), interpreting the work of Crang (1998), defined othering as a process in which an unequal and oppositional relationship between an in-group and out-group is established. The unequal and oppositional relationship pivots around perceived desirable characteristics of the in-group or perceived undesirable characteristics of the out-group. According to the participants’ accounts, students engaged othering with respect to the Black faculty members. That is, the Black faculty participants reported students’ enactments of conscious and subconscious beliefs that the Black faculty members were inferior. Student othering was blatant in the accounts of Damon and Dee: students’ poor teaching evaluations were accepted without scrutiny by and elicited action from Damon’s and Dee’s supervisors. Student othering was more tacit in the cases of Dan and Danielle; student comments conveying low expectations and the inscription of the instructor for Dan and Danielle, respectively, signified student othering.

Section III: race consciousness and racism in the participants’ experiences

The study participants shared their specific experiences and the researchers examined commonalities across them. The individual and collective perspectives per se on the Black faculty members’ experiences corresponded with existent research; some of the findings reiterated the work lives of higher education faculty. When the accounts of the participants’ experiences were viewed through a racial lens, for the purposes of addressing the second research question, race consciousness and racism insights emerged.

Racism as pervasive and permanent (Bell 1992) and experiential knowledge of people of color as valid are key tenets of critical race theory, the framing for this study. The participants’ voices, their descriptions and discussions of their experiences, illustrated an awareness of race, race consciousness, and illuminated racism in higher education. The extent of this illustration and illumination differed across the participants.

Dan did not identify as African American possibly because he immigrated to the U.S. (Ogbu and Simon 1998). Race was less central in the description of his experiences in contrast to his study counterparts. On one hand, Dan did not mention race when he discussed his teaching and service; he only featured science. On the other hand, he named race when speaking about his research experiences except he spoke of race in terms of shifting from diversity and inclusion foci to topics more accepted in the wider scientific community. He specifically acknowledged the absence of Blacks in his spheres of influence and encouraged the involvement of Blacks in mainstream research agendas that did not directly pertain to the participation of people of color.

In contrast to Dan, the other participants indicated a greater degree of race consciousness. Race was prominent in their experiential accounts. Damon cited race as a factor in students’ evaluations of teaching and the assignments he received within his unit. Danielle included race as an influence in describing how she felt inscribed and unaccepted. Dee highlighted race in discussing her struggles in teaching and the lack of support during her adjustment to a predominantly White institution. Dee also acknowledged the niceness of her colleagues but how this niceness did not translate into support or guidance and the development of diverse faculty would only occur if diverse faculty did it. Additionally, Damon, Danielle, and Dee featured students of color and the concerns of people of color in their professional experiences. For example, Damon advocated for students of color and invested his efforts to “grow” the local program that was largely populated by them. Danielle mentored students of color, worked to educate teachers about the challenges facing children of color, and confronted educators about their disparaging views of these students. Like Damon and Danielle, Dee also mentored others with diverse faculty members in academe as her mentees.

Although race consciousness is necessary in order to combat racism, its preeminence is not a prerequisite for racism, defined in this study as power-satiated social and institutional practices that perpetuate an established superior-inferior hierarchical relationship among races. That is, racism exists with or without people’s conscious awareness of race, an assertion supported by this study’s findings. Racism was implicated in the participants’ accounts, including Dan’s in which race consciousness was less prevalent.

Racism was evident in the positioning of the Black faculty members. The locations signaled in their narratives mirrored the inferior positioning, nationally and globally, of the Black racial group. First, the Black faculty members’ chronicles indicated exclusion from important domains. Dan’s statement in his advice to novice faculty members “there are unwritten rules that I had to stumble to figure them out as I went along” showed he was excluded from or denied access to colleagues’ explicit sense-making of the unwritten rules. Dee also alluded to this sentiment when she discussed mentoring colleagues of color. “I even tell them some things they need to know in terms of culture—some little dos and don’ts, when you need to keep your mouth closed. I mean, things that are not written in the book but can make the difference between you staying and going.”

Second, the Black faculty members’ narratives indicated marginalization. Damon and Danielle were tapped for in-house program administrative duties but were bypassed when the college needed public representation. Damon stated, “I find that when it’s time to go meet a corporate sponsor, it’s not me. It’s someone who has the typical corporate demeanor, who is a professor also. I’m talking about all us being … on the same level.” Danielle, who worked at the same institution, independently echoed Damon’s opinion: “I don’t feel readily included in the picture. I think that there’s a lot of deferment to another colleague who is kind of very corporate looking and different ethnically than me.”

Third, the out-group location, a component of othering discussed in section II, signified by exclusion and marginalization was most remarkable in the instance in which the Black faculty members would have most likely been the in-group because of their faculty status. The out-group location was evident in students’ evaluations of Damon’s and Dee’s teaching. These cases exemplified what appeared to be an unequal and oppositional relationship with students, as implied by Dee’s following remarks about the science methods courses:

The other thing they resented was I tried to bring in a cultural understanding piece, and they tore up my evaluations saying ‘she’s trying to make us learn this culturally relevant stuff, this is … science methods courses.’ And what I did was I tried to bring in some of Geneva Gay’s stuff, some of Delpit’s stuff, … So I wanted them to understand the cultural issues that they could probably face in an urban school, and I had them actually read one piece by McIntosh.… they called me racist.

The out-group location was furthered illustrated in Damon’s accounts. According to Damon, the evaluations provided by students enrolled in one program heavily populated by Whites were anomalous in relation to his other course evaluations. Furthermore, the trend of lower ratings from the majority White program existed for other instructors; yet, he was reprimanded and the low student evaluations were included in his annual review. Dee shared a similar situation regarding her ordeal in the science methods courses: after she “got called to the carpet” by her chair for poor student evaluations of her teaching, the chair observed her class and “actually said…he thought [her] classroom culture was just fine…”

Discussion: Contours of the terrain

The findings indicated that the terrain of Black faculty members’ experiences resembled that of faculty at large. Their challenges, depicted in the participants’ own words, included dissatisfaction with endeavors and concerns about work overload (Jacobs and Winslow 2004), scarcity of time (Russell 2010), and heavy administrative work, featured in the literature on postsecondary faculty as the most time consuming and least enjoyable tasks among faculty (Rosser 2004). The participants’ accounts also signaled contours in the terrain that were unique for groups inferiorly positioned. These contours were layered on top of the existing terrain; that is, they were additions to the stresses, tensions, and challenges faced by postsecondary faculty at large. The participants’ narratives indicated these contours were related to race, social conflicts and interests emerging from different types of human bodies (Omi and Winant 1994), and racism, hierarchical superior-inferior relationships among races that are established and perpetuated by power enacted through social and institutional practices (Bonilla-Silva 1997). The lived professional experiences related to race and racism of the Black faculty members, experiences from which the majority of White faculty are exempt, contribute in a cyclic fashion to the decreasing quality of work life cited in the research on faculty in higher education.

As described in section III of the findings, the roles of race and racism were evident in various ways in the participants’ experiences. Race and racism exacerbated the work overload and associated stresses described in sections I and II of the findings, a state of affairs that is seemingly indicative of employment in higher education. Unlike faculty who are members of racial groups positively positioned in society and in academe, the Black faculty members in this study struggled with investing time and energy in endeavors expected of all academics while simultaneously devoting time and energy to activities marginalized in the academy. These non-mainstream and sometimes controversial activities included confronting diversity-related challenges and engaging other- and self-imposed expectations related to inclusion. The Black faculty in this study exemplified the essential roles of Black faculty contended in research: they valued service-related activities like mentoring (Allen-Castellitto and Maillard 2001), they were instrumental in the academic lives of students of color (Allen et al. 2000), and they voiced concerns pertinent to people of color (Griffin et al. 2011).

These services, though unnoticeable on a national level, addressed the U.S. STEM workforce demand by diversifying STEM majors and retaining students of color in STEM fields, goals publicly marketed as valuable by U.S. institutions of higher education. The mentoring efforts of this study’s participants covered a large segment of the STEM pipeline. Danielle confronted STEM teachers in order to improve the educational experiences of children of color and she mentored STEM undergraduates of color who were recruited by her employing institution. Damon advocated for STEM graduate students of color who sought him out because they knew he would understand their situations and worked to address their concerns through program development. Dee mentored other diverse postsecondary faculty. These efforts were in addition to rather than in lieu of their work with students and faculty among the institution’s general population. The existent research indicates that Black faculty are not rewarded but penalized, perhaps unintentionally, for this extra diversity-related service (Diggs et al. 2009), occurrences in the study participants’ accounts.

The Black faculty members in this study accrued tangible and intangible penalties. Damon and Dee were negatively evaluated in their faculty performance as a result of poor student evaluations of their teaching, manifestations of racism. On one hand, the student evaluations demonstrated personally mediated racism. The students held race-based assumptions about Black faculty (prejudice) and rated them accordingly (discrimination). On the other hand, the end result of the students’ evaluations—Damon and Dee reprimanded by supervisors—represented institutional racism, differential access by race to commodities. In this instance, White students, through their evaluations, were granted access by the supervisors to institutional validation and Damon and Dee were not. Personally mediated racism later enacted as institutional racism was also applicable to the e-portfolio situation described by Damon. Damon, with experience in establishing and maintaining an e-portfolio initiative at another institution, was initially excluded from the e-portfolio push for his unit but functioned in the background, a marginalized role, when the colleague, with no experience in e-portfolios, selected as the unit leader on the effort elicited Damon’s help. The other retributions are less tangible, operating psychologically rather than materially as was the case in the poor student evaluations and unit assignment situations.

The intangible damages were inflicted by racial micro aggressions, brief but commonplace encounters that convey negative messages (Solorzano et al., 2000). The study participants experienced micro insults, verbal commentary that demean a person’s identity or heritage, and micro invalidations, racial micro aggressions that devalue through excluding, marginalizing, or nullifying the experiential reality, thoughts, and feelings of people of color (Sue et al. 2007). Low expectations for learning imparted by undergraduate students’ comments to Dan every semester illustrated a micro insult. The students’ comment “I didn’t expect to learn this much in this class” was interpreted by Dan as a disparaging remark about his professional teaching identity as reflected in his response “what did you expect to learn—nothing?” Micro invalidations were palpable in the experiences described by Dee and Danielle. Dee’s exposure to micro invalidations by way of her narrative was localized to her teaching experience in the undergraduate science methods course, specifically the resistance of White students to developing cultural understanding about the non-White youth they would instruct in the future. Danielle voiced the existence of micro invalidations more globally, as though they were pervasive in her working environment: “I really wanna, I don’t know if it’s going to happen, but I really wanna feel like myself in the place that I’m working. Once you feel that you’ve been accepted for who you are…I think you can be more productive.”

Implications

The problem at large is faculty dissatisfaction with work life in higher education. Much of the research conducted on work life and job satisfaction in higher education was done in the 1980s and a small cadre of work re-emerged in the early 2000s. Because Black faculty constitute a small percentage of faculty in higher education; because their experiences are featured in a small corpus of literature; and because they have essential roles in diversifying the present and future faculties in STEM, a high-visibility area at present, this study focused on Black faculty in postsecondary science education. This study’s results replicated findings from earlier research on higher education faculty in general and faculty of color and Black faculty in particular. Its unique contribution is the exploration of race consciousness and the expanded view of racism in the experiences of Black faculty members.

The current findings may not be generalized to all Black faculty members in academe, but they can inform blueprints for addressing issues that affect Black faculty differently than their non-Black counterparts. This study’s themes are important starting points in addressing the challenges that are pertinent to Black faculty members. The themes can inform faculty and administrators of the kinds of challenges Black faculty members face and inform efforts to alleviate the challenges on one front and to equip Black faculty members to navigate them on another front.

The different levels at which the Black faculty participants experienced racism indicate that it is important for institutions to implement measures at various levels. Typically, higher education institutions generate system-wide policies or they honor decentralized efforts and accept in faith that efforts are sufficient at the department and program levels, the levels Black faculty engage on a daily basis. In light of the Black faculty members’ experiences of institutional and personally meditated racism and racial micro aggressions, institutions should replace the passive (e.g., included in policy text) system-wide or department level approach with a more active approach that integrates system-wide and department level policies. For example, most institutional policies include non-discriminatory clauses with respect to treatment but these institutional policies do not ensure that faculty who conduct performance evaluations of their Black colleagues are informed of personally mediated racism and racial micro aggressions and how they can manifest in student evaluations. Additional research on the experiences of Black faculty in postsecondary science education can offer insights to advance such complementariness of much needed initiatives. Such efforts can improve institutions of higher education in ways that increase the likelihood that larger numbers of Black faculty are recruited into and retained in higher education, specifically in STEM. The recruitment and retention of Black faculty enhance the diversity of higher education at the time of their recruitment and retention. Through the many ways in which Black faculty engage the academy’s students and the service they provide, often at their own professional and personal expense, they also ignite and replenish the cycle for future diversification of higher education.

References

Aleinikoff, A. T. (1991). A case for race consciousness. Columbia Law Review, 91(5), 1060–1125. doi:10.2307/1122845.

Allen, W. R., Epps, E. G., Guillory, E. A., Suh, S. A., & Bonnous-Hammarth, M. (2000). The Black academic: Faculty status among African Americans in the U.S. higher education. Journal of Negro Education, 69(1/2), 112–127. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2696268.

Allen-Castellitto, A. L., & Maillard, K. (2001). Student and faculty perspectives on Black Americans’ success in the White academy. The Negro Educational Review, 52(3), 89–99.

Atwater, M. M., Butler, M. B., Freeman, T., & Parsons, E. C. (2013). An examination of Black science teacher educator’s experiences with multicultural education, equity, and social justice. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 24(8), 1293–1313. doi:10.1007/s10972-013-9358-8.

Bell, D. (1992). Racial realism. Connecticut Law Review, 24(2), 363–380.

Bogdan, R., & Biklen, S. K. (2003). Qualitative research for education (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Bonilla-Silva, E. (1997). Rethinking racism: Toward a structural interpretation. American Sociological Review, 62(3), 465–480. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2657316.

Brons, L. (2015). Othering, an analysis. Transcience, 6(1), 69–90. http://www.transcience-journal.org/.

Byng, M. (2013). You can’t get there from here: A social process theory of racism and race. Critical Sociology, 39(5), 705–715. doi:10.1177/0896920512453180.

Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching (2015). The Carnegie classification of institutions of higher education. Retrieved May 2015 from http://carnegieclassifications.iu.edu/.

Crang, M. (1998). Cultural geography. London: Routledge.

Crenshaw, K. W. (2011). Twenty years of critical race theory: Looking back to move forward. Connecticut Law Review, 43(5), 1253–1352.

Delgado, R. (1989). Storytelling for oppositionists and others: A plea for narrative. Michigan Law Review, 87(8), 2411–2441. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1289308.

Diggs, G. A., Garrison-Wade, D. F., Estrada, D., & Galindo, R. (2009). Smiling faces and colored spaces: The experiences of faculty of color pursuing tenure in the academy. Urban Review, 41(4), 312–333. doi:10.1007/s11256-008-0113-y.

Frieson, N., Henriksson, C., & Saevi, T. (2012). Introduction. In N. Frieson, C. Henriksson, & T. Saevi (Eds.), Hermeneutic phenomenology in education: Method and practice (pp. 1–16). The Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

Gall, M. D., Gall, J. P., & Borg, W. R. (2007). Education research: An introduction (8th ed.). Boston: Pearson.

Gotanda, N. (2000). A critique of “Our constitution is color-blind”. In R. Delgado & J. Stefancic (Eds.), Critical race theory: The cutting edge (2nd ed., pp. 35–38). Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Griffin, K. A., Pifer, M. J., Humphrey, J. R., & Hazelwood, A. M. (2011). (Re) defining departure: Exploring Black professors’ experiences with and responses to racism and racial climate. American Journal of Education, 117(4), 495–526. doi:10.1086/660756.

Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1989). Fourth generation evaluation. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publication.

Ito, T. A., & Bartholow, B. D. (2009). The neural correlates of race. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(12), 524–531. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2009.10.002.

Jacobs, J. A., & Winslow, S. E. (2004). Overworked faculty: Job stresses and family demands. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 596, 104–129. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4127652.

Johnsrud, L. K. (2002). Measuring the quality of faculty and administrative worklife: Implications for college and university campuses. Research in Higher Education, 43(3), 379–395. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40196459.

Jones, C. P. (2000). Levels of racism: A theoretical framework and a gardener’s tale. American Journal of Public Health, 90(8), 1212–1215.

Kena, G., Musu-Gillette, L., Robinson, J., Wang, X., Rathbun, A., Zhang, J., Wilkinson-Flicker, S., Barmer, A., & Dunlop Velez, E. (2015). The condition of education 2015 (NCES 2015-144). Washington, DC: U. S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved May 2015 from http://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch.

Miles, M. B. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Mutegi, J. W. (2011). The inadequacies of “science for all” and the necessity and nature of a socially transformative curriculum approach for African American science education. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 48(3), 301–316. doi:10.1002/tea.20410.

National Science Foundation, National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (2015). Women, minorities, and persons with disabilities in science and engineering: 2015. Special report NSF 15-311. Arlington, VA. Retrieved August 2015 from http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/wmpd/.

Ogbu, J., & Simon, H. D. (1998). Voluntary and involuntary minorities: A cultural-ecological theory of school performance with some implications for education. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 29(2), 155–188. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3196181.

Olsen, D., Maple, S. A., & Stage, F. K. (1995). Women and minority faculty job satisfaction: Professional role interests, professional satisfactions, and institutional fit. The Journal of Higher Education, 66(3), 267–293. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2943892.

Omi, M., & Winant, H. (1994). Racial formation in the United States: From the 1960s to 1990s (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Parsons, E. C. (2008). Positionality of African Americans and a theoretical accommodation of it: Rethinking science education research. Science Education, 92(6), 1127–1144. doi:10.1002/sce.20273.