Abstract

Flavio Azevedo, Peggy Martalock and Tugba Keser challenge the ‘argumentation focus of science lessons’ and propose that through a ‘design-based approach’ emergent conversations with the teacher offer possibilities for different types of discussions to enhance pedagogical discourse in science classrooms. This important paper offers a “preliminary contribution to a general theory” regarding the link between activity types and discourse practices. Azevedo, Martalock and Keser offer a general perspective with a sociocultural framing for analysis of classroom discourse. Interestingly the specific concepts drawn upon are from conversation analysis; there are few sociocultural concepts explored in detail. Therefore, in this article we focus on a cultural historical (Vygotsky in The collected works of L. S. Vygotsky. The history and development of higher mental functions, vol 4. Plenum Press, New York, 1987; The Vygotsky reader. Black, Cambridge, 1994) methodology to explore, analyse and explain how we would use a different theoretical lens. We argue that a cultural historical reading of argumentation in science lessons and design based activity will expand Azevedo, Martalock and Keser’s proposed general theory of activity types and discourse practices. Specifically, we use Lev Vygotksy’s idea of perezhivanie as the unit of analysis to reconceptualise this important paper. We focus on the holistic category of students’ emotional experience through discourse while developing scientific awareness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

This response paper focuses on using a cultural historical methodology. We begin by offering a brief synopsis of Avezedo, Martalock and Keser’s article and how we see the relation between design activity, discourse and student argumentation as proposed by the authors. We expand this conceptualisation by discussing the relations between the student and their environment as the source of development (Vygotsky 1994). This is further explained by illustrating our understanding of perezhivanie, which is understood as the students’ emotional experiences in the relations between personal characteristics and the social and material environment (Vygotsky 1994). We offer an example of our interpretation of a cultural historical data collection method and analysis. We draw on data provided by Avezedo, Martalock and Keser to illustrate how we would use perezhivanie as the unit of analysis. We explain and illustrate how our method of data collection and analysis differs from the authors’ method. This results in reviewing the questioning discourse offered by the teacher and students, which produces a different focus to that of the authors.

Azevedo, Martalock and Keser’s article seeks to combine activity types and epistemological discourse in science learning environments through the use of case examples, which outline and characterize the discourse practices of a design-based science classroom. Students are tasked with designing pictorial representations of moving objects either individually or in small groups through inventing graphing (IG). On completion of their first design, students are encouraged to present and explain their product to gain feedback in the form of argumentation discourse from peers and the teacher to use in subsequent iterations of the design process. According to Azevedo, Martalock and Keser the importance rests with “aiding rich pedagogical discourse in science classrooms”.

The authors frame and propose an informed argument towards the positive use of students’ iteratively designing and refining an artefact in the context of whole classroom discussion with teacher input, noting that “To engage students in such discourse practices therefore is to provide them with opportunities to participate in core aspects of scientific disciplines” (Azevedo, Martalock and Keser). The authors choose a broad theoretical framework to advocate this point and seek to combine a sociocultural framing with situative frames of learning (Greeno 2006), conversation analysis (CA) (Sacks, Schegloff, and Jefferson 1974) and interaction analysis (Jordan and Henderson 1995).

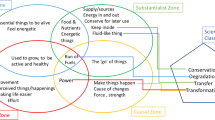

Azevedo, Martalock and Keser consider June Lave and Etienne Wenger’s (1991) socio-cultural framing as central to their work and note the reflexive relation between participation, discourse, knowing and learning. The authors acknowledge that student learning should be “a natural outgrowth of [their] project” and challenge others to extend this important point. The focus in Azevedo, Martalock and Keser’s article relates to students’ developing the use of argumentation through activity type and discourse, which we conceptualise in Fig. 1.

In this conceptualization, the students’ experience of the situation is not explicit. We seek to extend this conceptualisation through using Lev Vygtosky’s (1987) cultural historical theory and the concept of perezhivanie. We apply the concept of perezhivanie to the developing scientific awareness evident in the classroom discourse presented in Azevedo, Martalock and Keser’s article. We believe this new focus supports the authors’ informed position in generating a stronger theoretical basis for an initial general theory in relation to discourse practices and design activity in science classrooms.

Reconceptualising discourse from a cultural–historical perspective

The significance of Vygotsky’s cultural–historical theoretical work for furthering Azevedo, Martalock and Keser’s argument will become clear as we work through an analysis of the discourse of scientific classroom practices in this response. Using a cultural historical reading, the focus is on the dialectical relations between the student and the environment as the source of development (Vygotsky 1994). Development begins in social interaction, learning from and with others and then moves to an individual understanding, where the students can work by themselves and gain scientific understanding and awareness (Vygotsky 1987). Vygotsky (1989) relates emotions, actions and consciousness; Roth (2007) agrees with this argument by stating, “there are inner relations between emotion and practical activity that make the former a constitutive element of the latter” (p. 45). In this response paper it is the students’ relations with practical activity, each other and the teacher that is our main focus.

Vygotsky (1994) discusses the role of the environment in relation to students’ development, using the concept of perezhivanie. In this conception it is the “unity of personal characteristics and situational characteristics” (Vygotsky 1994, p. 341) which comes to the fore. Roth (2007) suggests that emotions have a collective dimension through the individual’s participation in social situations. The individual emotional experience (perezhivanie) of the student is inextricably linked with and formed through, the collective experience of the classroom environment. Reciprocal relations and the ensuing emotions are shaped individually and collectively. A recent study by Jennifer Schmidt, Elena Lyutkh and Lee Shumow (2012) places the idea of perezhivanie in the context of high school science learning and teaching. Here we use this concept to advance the theorization proposed in Azevedo, Martalock and Keser’s article. Our approach considers a holistic interpretation of perezhivanie, in contrast to the tightly framed view of perezhivanie put forward by Schmidt et al. (2012) that attempts to relate students’ subjective experience with teacher discourse. It is noted that important considerations such as teacher personality, experience and relations with students are reduced to ‘compounding variables’ whereas in this response, these aspects are essential to understanding perezhivanie in the classroom situation.

Considering the student and environment as a unity: introducing perezhivanie

Perezhivanie is increasingly used in the original Russian because translation into English does not fully explain its rich and multifaceted nature (for further theorization, see Gonzalez Rey 2009). In this paper we use the concept of perezhivanie as an integral part of Vygotsky’s whole system of concepts (for explanation see Chaiklin 2003). Vygotsky explains perezhivanie:

The emotional experience (perezhivanie) arising from any situation or from any aspect of his [sic] environment determines what kind of influence this situation or this environment will have on the child. Therefore it is not any of the factors in themselves (if taken without reference to the [student] which determines how they will influence the future course of his (sic) development, but the same factors refracted through the prism of the [student’s] emotional experience (perezhivanie). (Vygotsky 1994, p. 339)

The student and the environment (social and material) are considered active agents in the process of meaning making, understanding and consciousness. As Vygotsky (1994) outlines, it is the dialectical relations between these active agents that need to be explored. The student’s pezhivanie is an indivisible unity of the situational characteristics (collective) and personal characteristics (individual). It is this unity and the intense emotional nature of students experiencing this unity, that Vygotsky refers to as the “prism” refracting the social and material environment. Thus perezhivanie is a collective and an individual concept and one that needs to be explored further in the area of education in general and science education in particular.

The model in Fig. 2 foregrounds the relations between the environment and student. These relations are dynamic and change as students move through their everyday lives. Rather than measuring the emotional indicators (as was done in the study by Schmidt et al. 2012), Vygotsky’s focus is “finding the particular prism” which we interpret as investigating the relation that exists between the student and their environment; seeking to understand how the student “becomes aware of, interprets, [and] emotionally relates to a certain event” (Vygotsky 1994, p. 341). We propose to extend Azevedo, Martalock and Keser’s article using perezhivanie allowing a richness to emerge from the data as this concept encompasses the students’ and teachers’ past experiences, the social relations and the material aspects of the learning environment. On an individual level, the personal characteristics of each student ensure that “different events elicit different emotional experiences [perezhivaniya]” (Vygotsky 1994, p. 341).

Differing levels of awareness and insight means that some students are able to generalise more than others when considering representation in IG. Students react differently when being questioned by the teacher and peers. This is dependent on their past experiences and understanding of the situation and how they are experiencing it emotionally at that moment. In the classroom environment a teacher’s question or questioning style needs to be considered as part of the social and material environment that interacts with the student’s personal characteristics and has the potential to elicit a different perezhivanie in each student. Christine Chin (2006) using Jay Lemke’s (1990) work suggests that a traditional science classroom operates with the teacher asking a closed information seeking question, expecting a short answer that is based on “recall or [at a] lower-order cognitive level” (Chin 2006, p. 1316). The student answering is either praised or corrected (Chin 2006). Troy Sadler (2009) agrees and suggests that teachers are the experts and adds that students work at gaining facts and understanding so they can pass exams. “Students’ practices are often motivated by the perceived need to figure out what the teacher wants them to know” (p. 7). Just as important, but an often overlooked area, is students’ questioning. As Pei-Ling Hsu (2007) states, “when students question, they seek meaning and understanding, construct knowledge and reconceptualize what they already understand in a different way. They in fact are connecting new ideas and linking them to what they already know” (p. 282). The concept of perezhivanie allows us to go beyond the whole class analysis and take into consideration the individual student’s emotional relation to the collective situation. As Vygotsky explains:

An emotional experience (perezhivanie) is a unit where, on the one hand, in an indivisible state, the environment is represented, i.e. that which is being experienced – an emotional experience (perezhivanie) is always related to something which is found outside the person – and on the other hand, what is represented is how I, myself, am experiencing this, i.e., all the personal characteristics and all the environmental characteristics are represented in an emotional experience (perezhivanie)… So, in an emotional experience (perezhivanie) we are always dealing with an indivisible unity of personal characteristics and situational characteristics, which are represented in the emotional experience (perezhivanie). (Vygotsky 1994, p. 341)

When advocating perezhivanie as the unit of analysis, Vygotsky argues that the focus should be on units “which do not lose any of the properties which are characteristic of the whole” (1994, p. 341). We believe that analyzing teacher questioning in isolation does lose some properties characteristic of the whole (the unity of personal and environmental characteristics). Perezhivanie offers a different way of analyzing the data which takes into account individual and collective experience, relations, emotion and personality within the complex social environment of the classroom.

A different perspective on the process of discourse practices

Azevedo, Martalock and Keser propose that by “comparing and contrasting” across different research sites their theoretical program is delineated and the similarities and differences of discourse practices provide a comprehensive representation of the discourse used. Using a cultural historical reading of the proposed study, we advocate a single-case study at one research site (see Roth 2007, for example) and consider each focus participant’s perspective (Hedegaard and Fleer 2008). We argue that this systematic and holistic approach offers a solid foundation for building a general theory.

Differences in our method in comparison to Azevedo, Martalock and Keser begin at the initial stages of the research, in formulating the study design and deciding the type of data to collect, as the theoretical orientation influences approaches to data collection (Hedegaard and Fleer 2008). A cultural–historical orientation would focus on the original small group phases in order to understand the origin of discourse patterns before they are presented in the whole class situation. Azevedo, Martalock and Keser note:

We did record one episode of arguing at UTDP, but it took place among members of a group while they worked on re-designing their representation and discussed their ideas with the teacher—i.e., outside the public, whole-class sphere of discourse that is our analytical focus.

In Avezedo, Martalock and Keser’s article, there are instances during whole class discussions where multiple overlapping points of view and background comments are noted as ‘inaudible’ in the data. It would be consistent with our approach to examine the video recordings for the affective dimension building in these possibly intense segments and for evidence of collective arguing developing across the group; the collective perezhivanie of the group.

A further difference in our approach becomes apparent in the analysis stage. Using a cultural historical method, relational patterns in the video data are analysed and video clips are generated which can then be re-analysed in relation to the central concept(s) arising from the research question (Hedegaard and Fleer 2008). When new insights are gained, the video data is revisited and consulted for evidence. In Azevedo, Martalock and Keser’s article, the orientation informing data transcription is codified according to the conventions adapted from Rogers Hall and Reed Stevens (1995) and analysis of discourse practices proceeds from the transcript (Hsu 2007). Thus thematic analysis in the later stages is influenced by these earlier decisions. The transcription convention presented by Avezedo, Martalock and Keser includes non-verbal factors such as gestures, for example, holding up a representation. We would collect data that includes direction of gaze and the affective dimension that are needed for an analysis in relation to perezhivanie (all non verbal cues and group dynamics and apparent relations). From the video clips we then write “vignettes” which make explicit the researcher’s perspective and what is happening in the social and material environment and the relations from the student’s perspective.

The intensity of social relations is a key factor in the cultural–historical approach. The authors argue against analysing this more “complex” activity sequence as they wish to obtain “quick analytical gains…while avoiding complications” (Azevedo, Martalock and Keser). It is suggested that in the small group settings and through viewing the ‘inaudible’ data there is potential for highlighting the emotional relations, between the students and between the teacher and students. From here we would analyse how the students experience variations of discourse within the context of the classroom situation. We believe that using perezhivanie as the unit of analysis, rather than the “grain size” of “turns-at-talk” (Azevedo, Martalock and Keser) preserves the unity of “environmental and personal features” (Vygotsky 1994, p. 342). Thus we advocate a focus on the origin and the process rather than the resulting classroom discourse; on the small group and individual experience of the students and teacher engaging together in IG design-based activity and on systematically analysing and re-analysing video data, rather than transcripts.

Focusing on the origin and the process

To develop perezhivanie as the unit of analysis, we would interview each participant soon after the data sets were gathered and show the video to the participants, seeking clarification and comments. Rather than “comparing and contrasting” across sites we would follow the same participants over a period of time. This would enable a more in depth examination of the data allowing the students’ perezhivanie to emerge. In particular it would be important to ascertain the students’ attitude to the teacher’s questioning and how this shows the students’ developing scientific awareness. Using perezhivanie as the unit of analysis we would ask what each participant is trying to achieve with their questioning; what does each question mean for the student, how does each student perceive their teacher’s or peer’s intent? For example does the student feel that the questioning is designed to find out what they know, or do they perhaps interpret the question as a personal criticism or recognition of their ability to answer the question? A more in depth examination of questioning has the potential to result in a comprehensive form of analysis from each participant’s perspective and show each student’s developing scientific awareness. Thus perezhivanie provides a solid foundation to build a general theory of science classroom discourse.

Azevedo, Martalock and Keser note that Katherine McNeill and Diane Pimentel (2009) use “dialogicality to ascertain the students’ ability to state their position and the way in which their peers’ positions are addressed”. However, Azevedo, Martalock and Keser analyse the whole class process of design and redesign where “the teacher can have the most impact by orchestrating substantive and productive discursive practice among all participants’’. The traditional power positioning of the teacher is evident, where the teacher maintains control of the activity and the line of discourse that follows. Using perezhivanie as the unit of analysis focuses attention away from the teacher’s discursive practices towards other variables. These variables include the whole process of IG, individual and small group interaction within the whole class, the teacher’s personality, the students’ relations with each other and the teacher, the emotional nature of these relations and what effect these have on the environment and each student’s developing scientific awareness.

To use the initial teacher discourse, group conversation and interaction with the teacher, coupled with the background comments enables the analysis of the whole process of development of the students’ emerging scientific awareness (Vygotsky 1987) during the design of IG and not solely the analysis of conversation surrounding the product of IG. We propose that by using the whole process, strength is added to the main rationale behind the article, “To engage students in such discourse practices, therefore, is to provide them with opportunities to participate in core aspects of scientific disciplines” (Azevedo, Martalock and Keser).

Analysing the data using perezhivanie as the unit of analysis

To add substance to our argument we have drawn on the rich data from Azevedo, Martalock and Keser’s article and used perezhivanie as the unit of analysis. In our cultural–historical analysis we have interpreted the data taking into account Azevedo, Martalock and Keser’s goal to uncover the discourse practices characteristic of IG activities stated in their research question “What are the students and teacher doing as a whole and how is this reflected in their talk and action?”. We have combined this with the aims of our response to use perezhivanie as the unit of analysis.

Data Set One has been chosen from Benson Middle School (Azevedo, Martalock and Keser’s article). In this example, we have used the teacher and the students Steve and Andrea’s contribution to the whole class conversation for analysis, as this subset incorporates emotions. The information in this data set was relevant to Azevedo, Martalock and Keser’s aims and analysis. By focusing the analysis on day one of the study, the data presented from Benson Middle School is limited to audio recordings and field notes, precluding the possibility of revisiting the video data for non-verbal cues not evident in the field notes and audio. This data set reveals some important possibilities for thematic analysis using perezhivanie.

Important turns of talk in Avezedo, Martalock and Keser’s Data Set One

In the first four turns at talk (TT) we see the teacher posing a general question and later answering for Steve. We cannot ascertain if Steve was invited into the conversation by non-verbal gestures (eye contact, movement of participants) but it is noted in the analysis that he lifts his representation at TT4. The teacher and students talk about and for Steve’s representation of IG from TT4 to TT9. TT10 is the first time that Steve enters the discussion. At TT12 Steve re-enters the conversation but is treated in the same manner as Andrea (talked over). TT13 returns to Andrea who suggests that Steve should use something that relates to the picture. In TT14 Steve asks what relates to his representation. By TT17 Andrea has returned to the question a third time discounting Steve’s answer. Finally in TT18 the teacher interjects and asks the whole class for their personal opinion regarding other suggestions.

Emerging perezhivanie

Using CA would draw the attention to Andrea and the teacher as they have the most TT and seem to keep the discussion moving. But using perezhivanie highlights Steve’s contribution to the discourse of the classroom; although he had only three TT, they were important.

The audio recording and field notes from the first day of the study are seen as a static representation of data collection, whereas Marilyn Fleer (2008) argues for the use of digital video recording in conjunction with field notes as these offer a dynamic system to which the researcher can return to review the dynamics and the relational patterns of the situation. Azevedo, Martalock and Keser’s transcription is based on the first hour of the design based IG scenario. Hsu notes that “Many studies have their own conventions for transcription” (2007, p. 287) and as in this case, the interpretation of the transcription is left to the reader.

Individual perezhivanie

Using a cultural–historical approach we analyse the transcript from Steve’s perspective. We examine Steve’s individual perezhivanie using Data Set One as an example. We note that this episode presented in Azevedo, Martalock and Keser immediately follows a class discussion where the students and teacher became aware of each other’s approach to representing zero velocity and that Steve’s representation shows an incorrect motion pattern. Steve holds up his representation (TT4) and the group are addressing this material aspect (Vygotsky 1994) of their classroom environment. We see that when Steve enters the discussion at TT10, he uses a question “What are you going to use?” He seems disengaged and shows no ownership of his representation. Steve uses the word “you” when talking about his own design. Here Steve could be experiencing a range of emotions from being quite proud of himself “They like and are talking about my good work” to embarrassed “They are criticising and don’t like my work”. In our post video interviews we would ask Steve about his feelings at this moment and whether or not he understood the task. We would also seek to find out which of Steve’s personal characteristics were pertinent in relation to this situation (Vygotsky 1994). Steve’s reticence to put himself forward could indicate that he is not an outgoing person, or he may feel his scientific understanding does not meet the expectations set within the classroom. He allows others to talk about his design up to TT10 without comment or interjection. From this it is difficult to determine Steve’s social position within the group. We can see from this brief analysis that the complexity of relations between personal and environmental characteristics is intertwined with the affective aspects of individual participants and this is how we interpret Vygotsky’s (1994) use of the concept perezhivanie. Here we have considered the individual perezhivanie of Steve but perezhivanie needs to be considered both as an individual and a collective concept. Next, we consider the collective perezhivanie in the classroom as Andrea re-enters the discussion.

Collective perezhivanie

When considering the collective perezhivanie of the classroom we continue to draw on Data Set One as an example. In TT13 Andrea’s power positioning emerges as she (once again) asks the whole class to wait while she forms an answer. From her answer, we can interpret a possible range of emotions, from empathy as she realises that Steve needs help with his interpretation, to the possibility of acting like a teacher and giving Steve a hint of what to do but not telling him explicitly her meaning (Sadler 2009). It emerges that Andrea may be aware of the teacher’s discourse and has modelled her response on the way the teacher had answered a question that he had posed (TT4). In TT17 Andrea returns to the question a third time and provides a clear indication of emotion in her emphatic use of the word “YOU” addressed at Steve. This analysis provides an example of the collective concept of perezhivanie: The relations between the social environment, material environment and the pertinent personal characteristics of Steve and Andrea are indivisible. The participants are drawn together and are emotionally experiencing the whole class dynamics of the discussion. Azevedo, Martalock and Keser identified a special quality about the data presented in turns 2–18 of this data set, referring to an “identifiable moment in which, as a whole, participants oriented themselves toward a common goal within the larger flow of the activity”. We believe that using perezhivanie as the unit of analysis enables a deep theoretical exposition of this “moment”, “common goal” and “flow of activity” by showing the unity of social, material and personal characteristics entwined with the emotional tensions and intensity in the classroom experience.

Questioning the questions

Using individual and collective perezhivanie enables analysis of how students generalise their scientific awareness (Vygotsky 1987) in relation to IG discourse. We see Steve and Andrea operating differently within the classroom, Steve is quiet and allowing others to talk about his representation until TT10 but then he seems to acknowledge that the class are trying to help him and asks what they would use. In contrast, Andrea is active from the beginning of the transcript and continues to question, in fact posing the same question three times (TT5, 7, 9). Only being able to analyse from the transcript of Azevedo, Martalock and Keser’s article we offer two hypotheses. Andrea is taking the role of a traditional teacher and is asking a closed information seeking question and expecting a short answer (Chin 2006) or she may be trying to seek meaning by connecting ideas and linking them to her past experience or own IG representation (Hsu 2007). In TT18 the teacher singles out individuals and then asks the whole group and challenges the class that if they don’t “personally like the equal sign” to speak up. Is the teacher showing frustration or trying to extend the discourse? Here we see a personal questioning pedagogy, an emotive style of questioning and the possibility that the teacher recognises that students have different understanding and scientific awareness of the concepts with in IG.

Concluding comments

Azevedo, Martalock and Keser’s informed position makes an important contribution to understanding and forming the initial stages of a general theory in relation to discourse practices and design activity in science classrooms. Our commentary rises to the challenge set by the authors, which is to engage others to contribute to the long-term development of the general theory. Our commentary proposes that a robust theorisation needs to occur prior to formulation of a general theory. Vygotsky’s (1987, 1994) work offers a useful methodology and theorisation of the ideas put forward by Azevedo, Martalock and Keser and provides a different view than is offered by the authors. This theorization advocates for a different analysis of discourse through the use of perezhivanie as the unit of analysis.

Through the use of Vygotsky’s (1994) concept of perezhivanie as the unit of analysis, we make visible the importance of approaching the research question from a theoretical point of view. Through using Azevedo, Martalock and Keser’s data our analysis shows a possible range of emotions that students may feel during participating in a science classroom. The analysis offers different perspectives of participants, specifically the important role that both the teacher and students undertake in building discourse through their common use of statements, questions and interactions in the science classroom. The student’s attitude to questioning and questioning as a meaning making process, rather than questioning style, comes to the fore in our analysis. We suggest that the role of the relational aspects together with the “inner relations between emotion and practical activity” (Roth 2007) in the type of discourse offered by each student needs to be explored further.

We have demonstrated how Vygotsky’s cultural historical theory (1987, 1994), specifically the concept of perezhivanie, can develop Azevedo, Martalock and Keser’s informed position in generating a stronger theoretical basis for an initial general theory in relation to discourse practices and design activity in science classrooms. We agree that this is an important contribution to science classroom development and high school science teaching and learning but an enormous task and will succeed if there is collective work on the project.

References

Chaiklin, S. (2003). The zone of proximal development in Vygotsky’s analysis of learning and instruction. In A. Kozulin, B. Gindis, V. S. Ageyev, & S. M. Miller (Eds.), Vygotsky’s educational theory in cultural context (pp. 39–64). NewYork: Cambridge University Press.

Chin, C. (2006). Classroom interaction in science: Teacher questioning and feedback to students’ responses. International Journal of Science Education, 28, 1315–1346. doi:10.1080/09500690600621100.

Fleer, M. (2008). Using digital video observations and computer technologies in a cultural–historical approach. In M. Hedegaard, M. Fleer, J. Bang, & P. Hviid (Eds.), Studying children: A cultural–historical approach (pp. 104–117). Maidenhead, England: Open University Press.

Gonzalez Rey, F. (2009). Historical relevance of Vygotsky’s work: Its significance for a new approach to the problem of subjectivity in psychology. Outlines. Critical Practice Studies, 11, 59–73.

Greeno, J. G. (2006). Learning in activity. In R. K. Sawyer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences (pp. 79–96). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hall, R., & Stevens, R. (1995). Making space: A comparison of mathematical work in school and professional design practices. In S. L. Star (Ed.), The cultures of computing (pp. 118–145). Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Hedegaard, M., & Fleer, M. (2008). Studying children: A cultural–historical approach. Maidenhead, England; New York: Open University Press.

Hsu, P. (2007). Forum: Questions as a tool for bridging science and everyday language games. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 2, 281–303. doi:10.1007/s11422-007-9053-1.

Jordan, B., & Henderson, A. (1995). Interaction analysis: Foundations and practice. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 4, 39–103. doi:10.1207/s15327809jls0401_2.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Lemke, J. L. (1990). Talking science: Language, learning, and values. Westport, CT: Ablex.

McNeill, K., & Pimental, D. (2009). Scientific discourse in three urban classrooms: The role of the teacher in engaging high school students in argumentation. Interscience, 94, 203–209. doi:10.1002/20364.

Roth, W.-M. (2007). Emotion and work: A contribution to third-generation cultural–historical activity theory. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 14, 40–63. doi:10.1080/10749030701307705.

Sacks, H., Schegloff, E. A., & Jefferson, G. (1974). A simplest systematic for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language, 50, 696–735. doi:10.2307/412243.

Sadler, T. (2009). Situated learning in science education: Socio-scientific issues as contexts for practice. Studies in Science Education, 45, 1–42. doi:10.1080/03057260802681839.

Schmidt, J., Lyutkh, E., & Shumow, L. (2012). A study of teachers’ speech and students’ perezhivanie in high school physics classrooms. Northern Illinois University. In Paper presented at the annual meetings of the American Educational Research Association, Vancouver, BC.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1987). Thinking and speech (N. Minick, Trans.). In R. W. Rieber & A. S. Carton (Eds.), The collected works of L. S. Vygotsky. The history and development of higher mental functions (Vol. 4). New York: Plenum Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1989). Concrete human Psychology. Journal of Russian and East European Psychology, 27, 53–77. doi:10.2753/RPO1061-0405270253.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1994). The problem of the environment. In R. van der Veer & J. Valsiner (Eds.), The Vygotsky reader. Cambridge, MA: Black.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge with thanks the help and guidance of Professor Marilyn Fleer and acknowledge the monthly Dialectical Logic Learning Space (DLSS) reading group conversations led expertly by A/Professor Nikolai Veresov, which have been instrumental in guiding our understanding of perezhivanie as a concept.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Forum: This review essay addresses Flavio Azevedo, Peggy Martalock and Tugba Keser’s paper entitled: The discourse of design-based science classroom activities.

Lead Editor: M. Fleer.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Adams, M., March, S. Perezhivanie and classroom discourse: a cultural–historical perspective on “Discourse of design based science classroom activities”. Cult Stud of Sci Educ 10, 317–327 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-014-9574-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-014-9574-3