Abstract

This study proposes that police officers’ supervisors might be unfairly treated by their subordinates. Supervisors would respond in a forgiving or revengeful manner to unfair treatment by a subordinate, and their responses might influence their subordinates’ effectiveness. Thus, this study investigated the relationship between perceived unfair treatment by a subordinate (PUTS), supervisor forgiveness and revenge response, and subordinate effectiveness, and tested the moderating effect of supervisor affective organizational commitment. A group-based survey was conducted in a Taiwanese law enforcement organization, and 93 supervisors and 389 subordinates returned questionnaires. The multi-level analysis showed that (a) PUTS was negatively associated with supervisory forgiveness; (b) supervisory forgiveness was positively related to job performance, cooperative behavior, and proactive behavior; (c) supervisory forgiveness mediated the relationship between PUTS, job performance, and proactive behavior; and (d) supervisors with high affective organizational commitment were more likely to act revengefully toward PUTS than to those with low affective organizational commitment. The findings showed that PUTS is a meaningful construct and that supervisor forgiveness is critical to a positive social exchange between police officers and their supervisors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Organizational justice or fairness perception is critical in organizational behavior studies (Fischer et al., 2011) and has been found to be vital to a wide range of employee and organizational effectiveness outcomes (Colquitt et al., 2001) and to employee health (Greenberg, 2010). For example, a study showed that perceived fairness in the organization, such as fair treatment by the organization or supervisor, is an antecedent of employees’ loyalty to and voice within the organization (Cropanzano et al., 2007). Equity theory explains that justice is essential to employees’ organizational life because the perception of injustice or unfairness motivates individuals to behave to make things fair (Adams, 1965; Greenberg, 1987). Almost all studies have focused on the fairness perception of employees, and very few have examined the fairness perception of supervisors (with the rare exception of Liu et al., 2017), especially supervisors who perceived unfair treatment by their subordinates.

As supervisors have higher formal power over their subordinates (Yukl, 2002), researchers might consider it more likely for supervisors to be unfairly treated by the organization or higher-level supervisors than by their subordinates (Liu et al., 2017). However, supervisors could be mistreated by their subordinates (Cheng, 1995; Elangovan & Shapriro, 1998) and might react in certain ways to such unfair treatment (Tepper et al., 2006). In the workplace, subordinates might show disrespect to their supervisor or form a small group to bargain with the supervisor, and supervisors might even be betrayed by their trusted subordinates. Supervisors might react with abuse or authoritarianism to restore their sense of justice and status (Farh & Cheng, 2000; Tepper et al., 2006).

Revenge behavior involves lowering the offender’s resource or status to get even and follows the rule of retributive justice (Stuckless & Goranson, 1992). Although revenge is the quickest way to get even, this behavior could be very inappropriate for an effective leader (Tripp et al., 2007). Forgiveness is withholding the right to revenge and showing compassion and empathy toward the offender, which follows the principle of restorative justice (Bradfield & Aquino, 1999; Wenzel et al., 2008). Fehr and Gelfand (2012) showed that forgiveness can promote positive social exchange and enhance group effectiveness. Thus, we investigated the relationship between supervisors’ perception of unfair treatment by a subordinate (PUTS) and supervisors’ revenge and forgiveness. Based on the social exchange perspective (Blau, 1964), supervisors’ forgiveness promotes positive exchange and fosters cohesion and trust (Tyler & Blader, 2003), and supervisors’ revenge leads to negative exchange and distrust (Greco et al., 2019). Accordingly, this study proposes that supervisors’ revenge and forgiveness mediates the relationship between PUTS and employee effectiveness, considered as job performance, cooperative behavior, and proactive behavior (Lam et al., 2014; Owens et al., 2016).

Supervisors’ affective organizational commitment refers to their emotional attachment to the organization, which might increase the positive relationship between PUTS and revenge reactions. According to the altruistic punishment perspective (Fehr & Gachter, 2002), supervisors might feel responsible for an organizational member’s deviant behavior and use punishing behavior to make the member cooperative. Thus, this study explores the moderating effect of supervisor affective commitment on the relationship between PUTS and supervisor revenge.

The need to understand justice and fairness within law enforcement organizations is reflected in an increasing number of studies (Reynolds et al., 2018; Trinkner & Cohn, 2014; Trinkner et al., 2018). As the relationship and interaction between supervisors and subordinates is critical in law enforcement organizations (Wolfe et al., 2018), this study investigated the relationship of interest in these organizations.

Supervisors’ Perception of Unfair Treatment by a Subordinate (PUTS)

Although workplace justice has been investigated for several decades, a review by Colquitt et al. (2001) showed that most studies have focused on the employee perspective. Studies have demonstrated that employee justice perception can promote job performance, organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB; for a meta-analysis, see Cohen-Charash & Spector, 2001). OCB is a discretionary behavior by organizational members that can benefit the organization, such as voice behavior and helping colleagues (Organ, 1988). Supervisors’ perception of fair treatment in the organization has rarely been studied. One recent study found that supervisors’ perception of unfair treatment by the organization influenced how they interacted with their subordinates, which lowered the subordinates’ prosocial and voice behavior (Liu et al., 2017). Police subcultures can exhibit unfair practices, such as brutality, authoritarianism, extreme conservatism, prejudice, and racism (Sayles & Albritton, 1999), which might make the interaction between supervisors and police officers less respectful and fair. In this way, supervisors could be unfairly treated by their subordinates (i.e., police officers) in the workplace of law enforcement organizations.

Equity theory proposes that when individuals feel that they have been treated unfairly, they are motivated to behave to decrease the feeling of unfairness (Adams, 1965). A subordinate might not reciprocate the supervisor’s support and benevolence (Cheng, 1995), might betray the supervisor’s trust (Elangovan & Shapiro, 1998), or might intentionally behave in a disrespectful manner in front of the supervisor (Pearson & Porath, 2005), thus giving the supervisor a perception of being unfairly treated by the subordinate. In response to PUTS, supervisors might take revenge or show leniency. Several items used in measures of leadership describe possible reactions to PUTS: for example, “my supervisor puts me down in front of others” (abusive supervision; Tepper, 2000), “my supervisor avenges a personal wrong in the name of public interest when he/she is offended” (moral leadership; Cheng et al., 2004), “my supervisor criticizes and blames outgroups in public” (differential leadership; Jiang et al., 2014), and “my supervisor turns a blind eye to ingroups’ mistakes” (differential leadership; Jiang et al., 2014). The above leadership studies have demonstrated that supervisors respond in ways that involve forgiveness or revenge.

Forgiveness and Revenge

Fair policing refers to police officers being willing to listen to citizens’ perspectives and treat citizens respectfully (Haas et al., 2015), for which the perception of justice between supervisors and police officers is critical (Bradford & Quinton, 2014). Furthermore, supervisors’ behavior sends crucial signals to officers regarding the moral standards of the organization (Rothstein & Stolle, 2008; Van Craen & Skogan, 2017). Therefore, supervisors’ responses to the PUTS might be influential on employee behavior, which might lead to fair policing. The responses of revenge and forgiveness reflect two perspectives of recovering justice: respectively, retributive justice and restorative justice (Goodstein & Butterfield, 2010; Strelan et al., 2008; Wenzel et al., 2008). Revenge is when someone who perceives they have been treated unfairly acts in a harmful manner in return (Stuckless & Goranson, 1992). In contrast, forgiveness is defined as reacting with compassion, benevolence, and caring, even when a person has the right to revenge (Bradfield & Aquino, 1999).

The nature of retributive justice is punishment, which involves depleting the offender’s resources, such as money, status, prestige, or freedom, to restore the balance the power between parties (Strelan et al., 2008). Reynolds et al. (2018) reported that police officers engaged in production deviance as a form of retaliation against perceived unfair treatment, such as reduced output by doing the bare minimum (Reynolds et al., 2018). The study of Aquino et al. (2006) indicated that people with greater power were more likely to act in a revengeful manner when facing unfair events. Supervisors have formal power over their subordinates and are less likely to be punished by exerting neglectful, critical, or less supportive behavior as revenge (Kremer & Stephens, 1983; Hodgins et al., 1996). Vengeance by supervisors could help them to regain a sense of justice and provide the opportunity to give feedback on subordinates’ lack of reciprocity behavior (Bies et al., 1997; Tripp & Bies, 2009). Supervisors might behave abusively, such as by engaging in hostile verbal and nonverbal behaviors (Tepper, 2000), and the long-term physiological and psychological tension inherent in police work can lead police officers to respond to minor conflicts or threats in a more aggressive manner (Griffin & Bernard, 2003). Furthermore, a recent study indicated that abusive supervision could temporarily enhance subordinates’ work engagement (Qin et al., 2018), potentially prompting supervisors who hold this belief to retaliate in a vengeful manner. Thus, supervisors might be encouraged or less hesitant to enact revenge when they experience PUTS. Similarly, supervisors might be less likely to show forgiveness when encountering PUTS.

-

H1: PUTS is positively associated with supervisor revenge behavior.

-

H2: PUTS is negatively associated with supervisor forgiveness behavior.

Supervisors’ Reactions and Employee Effectiveness

Social exchange theory proposes that social components, such as trust, friendship, and commitment, can be exchanged between individuals (Blau, 1964). Individuals who receive a favor from another feel obligated to reciprocate this favor, in a process called positive reciprocity (Greco et al., 2019). Whereas continuing positive social exchange can contribute to a high-quality relationship (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995), negative social components, such as hate and dislike, promote negative social exchange processes that can worsen the relationship (Greco et al., 2019). Accordingly, although revenge might make supervisors feel better and establish authority, it might trigger negative reciprocity, worsen the relationship between the supervisor and the subordinate, and influence employee effectiveness (Mitchell & Ambrose, 2007; Priesemuth et al., 2014; Qin et al., 2018). Studies on abusive supervision and authoritarian leadership have consistently shown that hostile leader behavior negatively influences elements of employee effectiveness, such as job performance, cooperative behavior, and proactive behavior (Farh & Cheng, 2000; Mitchell & Ambrose, 2007).

Restorative justice focuses on mutual benefit and long-term relationships rather than short-term benefit (Bradfield & Aquino, 1999; Exline et al., 2003; Fehr & Gelfand, 2012). Supervisors’ forgiveness could promote a positive reciprocity process (Greco et al., 2019; Witvliet et al., 2002). By expressing compassion and benevolence, a forgiving leader could make subordinates feel understanding and supportive and willing to contribute more to work to reciprocate the supervisor’s kindness (Farh & Cheng, 2000; Jiang & Cheng, 2008). Studies have indicated that supportive and benevolent leadership can promote many elements of employee effectiveness, such as job performance, cooperative behavior, and proactive behavior (Cheng et al., 2015; Podsakoff et al., 1996; Wu et al., 2012).

This study investigates three core elements of employee effectiveness: job performance (Owens et al., 2016), cooperative behavior (Tyler & Blader, 2003), and proactive behavior (Lam et al., 2014). Job performance, also called in-role performance, indicates the extent to which an employee accomplishes his/her duty correctly, efficiently, and effectively (Cheng et al., 2003). Cooperative behavior indicates the extent to which an employee complies with the rules and regulations of the organization and the group (Tyler & Blader, 2003). Employees’ proactive behavior, which refers to actively finding and resolving problems in the workplace, is critical to employee creativity and innovation (Lam et al., 2014). Recent studies have shown that these three outcomes are critical indicators of employee effectiveness when examined in relation with justice in the workplace (Colquitt et al., 2001; Tyler & Blader, 2003, 2013; Zhang et al., 2014). The study of Reynolds et al. (2018) showed that when police officers were not treated fairly, they behaved in a deviant and self-protective manner, exhibiting lower job performance, a reluctance to cooperate, and a tendency to lay low. Paoline III and Gau’s (2020) qualitative study indicated that when police officers felt supported, appreciated, and encouraged by their supervisors, they had high job satisfaction and promoted positive work behaviors. Forgiving supervisors demonstrate highly supportive behavior toward their subordinates. Thus, in line with the generalized social exchange perspective, we propose the following hypotheses:

-

H3: Supervisor revenge behavior is negatively associated with employee effectiveness (job performance, cooperative behavior, and proactive behavior).

-

H4: Supervisor forgiveness behavior is positively associated with employee effectiveness (job performance, cooperative behavior, and proactive behavior).

The Potential Mediation Effect of Supervisors’ Revenge and Forgiveness

PUTS might indirectly influence employee effectiveness through the mediation effect of supervisors’ revenge and forgiveness. From the social exchange perspective, restorative justice emphasizes the long-term relationship, which indicates a high-quality social exchange relationship (Blau, 1964; Greco et al., 2019), whereas retributive justice requires short-term fairness without considering positive social components or even introduces harmful social components as a form of revenge (Hodgins et al., 1996; Kremer & Stephens, 1983). Accordingly, PUTS might hamper employee effectiveness by increasing supervisors’ revenge and decreasing supervisors’ forgiveness. We therefore propose the fifth and sixth hypotheses as follows:

-

H5: Supervisor revenge mediates the relationship between PUTS and employee effectiveness.

-

H6: Supervisor forgiveness mediates the relationship between PUTS and employee effectiveness.

The Moderating Effect of Supervisor Affective Commitment

Tyler and Blader’s (2003) proposed group engagement model posits that groups use sanctions to promote cooperation and engagement among their members. The question remains, however, of which group member is responsible for the sanctioning decision and behavior. Organ (1988) argued that a committed employee would be proud of being an organizational member and act like a corporate soldier, protecting the organization’s benefit. Mayer and Allen (1991) and O’Reilly and Chatman (1986) proposed that affective organizational commitment represents an employee’s attachment to the organization, which means that the individual identifies and internalizes the organization’s vision and values. Thus, a committed supervisor might be more likely than one who is less committed to prioritize the welfare of the organization and the workgroup. This proposition is supported by recent findings that committed employees exhibit high levels of voice and proactive behavior (Loi et al., 2012; Parker et al., 2006; Van Dyne & LePine, 1998).

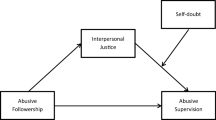

A committed supervisor will focus on the cohesiveness of the workgroup and might see PUTS as deviant behavior toward herself/himself and the workgroup as a whole. Fehr and Gächter (2002) proposed that group members engage in altruistic punishment, which involves punishing uncooperative members to maintain the group’s cohesiveness. This means that a committed supervisor might be prone to enact revenge for the workgroup’s sake. The same study showed that uncooperative members behaved cooperatively after their punishment (Fehr & Gachter, 2002). Thus, according to the altruistic punishment perspective, we expect that supervisors with high affective commitment to the organization tend to emphasize the benefit of the workgroup and the organization, and thus might be more likely to enact revenge for PUTS as they see it as a threat to the cohesiveness of the workgroup and the organization. As the altruistic punishment perspective explains punishment behavior within a group, supervisor affective commitment is less likely to moderate the relationship between PUTS and forgiveness. Accordingly, our final hypothesis is as follows and Fig. 1 shows the hypothesized study framework:

-

H7: Supervisor affective commitment moderates the relationship between PUTS and supervisor revenge, such that the positive relationship is greater when supervisor affective commitment is high than when it is low.

Methods

A group-based dyadic questionnaire survey was administered in January 2022 to 120 supervisors and 681 subordinates from a Taiwanese law enforcement organization. Ninety-three supervisor questionnaires and 389 subordinate questionnaires were returned, for a response rate of 83.03% and 57.12%, respectively. Approximately 92% of the supervisors and 83% of the subordinates were male. The mean number of subordinates under a supervisor was 4.18. The mean subordinate age was 41.46 years (SD = 10.81) and the mean supervisor age was 50.75 years (SD = 6.82). The mean supervisor and subordinate coworking period was 2.05 years (SD = 2.72). This study was approved by the institutional review board of the National Chung-Cheng University (CCUREC110051801).

Procedure

The researchers contacted a Taiwan law enforcement organization to invite them to join this study, and the organization accepted the proposal. Questionnaires with guidance were pre-coded to ensure anonymity and delivered with the help of the organization’s staff. After completing the questionnaire, the participants sealed it in an envelope prepared in advance, and the researchers collected the sealed questionnaires directly from the participants.

Measures

The translation–back-translation procedure was used to create a Traditional Chinese version of all measures (Brislin, 1986). The supervisor questionnaire comprised three sections, measuring PUTS (11 items), affective commitment (6 items), and demographic variables. The subordinate questionnaire comprised five sections, measuring the supervisor’s revenge and forgiveness behavior (11 items), job performance (4 items), cooperative behavior (15 items), proactive behavior (10 items), and demographic variables. All items were rated on a 6-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree.

Perceived Unfair Treatment by a Subordinate (PUTS)

The measure of PUTS was adapted from the justice perception measure of Niehoff and Moorman (1993) and the betrayal measure of Grégorie and Fisher (2008) and consists of an 11-item scale. Sample items are “When this subordinate reports difficulties with work tasks to me, he/she is honest and transparent without deception” (reversed coded), “I feel deceived by this subordinate,” and “I feel betrayed by this subordinate.” The supervisors were asked to rate each of their subordinates on this scale. Cronbach’s alpha of this scale was 0.91.

Supervisor Affective Commitment

Affective commitment was reported by the supervisor on a measure adapted from the 6-item affective organizational commitment scale of Meyer at el. (1993). Sample items are “I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this organization” and “I really feel as if this organization’s problems are my own.” Cronbach’s alpha of this scale is 0.84.

Supervisor Revenge

For the revenge measure, six items on revenge from Bradfield and Aquino (1999) were modified by changing the referent from “I” to “My supervisor” and the target from “them” to “me.” Sample items are “When I did something bad to my supervisor, he/she supervisor tried to make something bad happen to me,” “When I hurt my supervisor, he/she did something to make me pay,” and “When I didn’t treat my supervisor fairly, he/she got even with me.” Cronbach’s alpha of this scale was 0.95.

Supervisor Forgiveness

For the forgiveness measure, five items from Bradfield and Aquino (1999) were modified by changing the referent from “I” to “My supervisor” and the target from “them” to “me.” Sample items are “When I made mistakes, my supervisor gave me back a new start, a renewed relationship,” “My supervisor accepted my humanness, flaws, and failures,” and “Even when I made mistakes, my supervisor did his/her best to put aside the mistrust.” Cronbach’s alpha of this scale was 0.96.

Job Performance

The job performance measure was adapted from Farh and Cheng’s (1997) 4-item measure. Sample items are “I make an important contribution to the overall performance of our work unit” and “I am one of the excellent employees in our work unit.” Cronbach’s alpha of this scale was 0.90.

Cooperative Behavior

The cooperative behavior measure was adapted from Tyler and Blader (2001) and comprised an 8-item compliance measure and a 7-item deference measure. Sample items are “I follow work rules,” “I comply with company regulations,” and “Even if no one is around, I execute my supervisor’s order accurately.” Cronbach’s alpha of this scale was 0.80.

Proactive Behavior

The proactive behavior measure was adapted from Grant et al. (2009). This 10-item measure consists of three domains: voice, rational issue-selling, and taking charge. Sample items are “gets involved in issues that affect the quality of work life here in the group,” “goes about changing your mind to get you to agree with them,” and “tries to implement solutions to pressing organizational problems.” Cronbach’s alpha of this scale was 0.96.

Control Variables

Supervisors’ and subordinates’ age and gender were included as control variables. This study also controlled the effect of the coworking period with the supervisor.

Results

Before examining the proposed hypothesis, a confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to demonstrate discriminant validity among the studied variables. The confirmatory factor analysis showed a good fit for a six-factor model comprising PUTS, supervisor forgiveness, supervisor revenge, supervisor revenge, job performance, cooperative behavior, and proactive behavior, χ2 = 209.27, df = 120, root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.04, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.98, Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) = 0.98, standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR) = 0.03. Table 1 shows the confirmatory factor analysis results and indicates that the six-factor solution had the best fit.

Table 2 shows the correlations among the studied variables. PUTS was negatively associated with supervisor forgiveness (r = −.27, p < .01) and positively associated with supervisor revenge (r = .12, p < .05). Supervisor forgiveness was positively related to job performance, cooperative behavior, and proactive behavior (rs = 0.22–0.33, p < .01). Supervisor revenge was negatively related to job performance (r = −.15, p < .01) (Table 2).

Mplus Version 8.3 was used to perform multi-level path analysis to examine the proposed hypothesis. We adopted group-mean centering for Level 1 variables and grand-mean centering for the Level 2 variable. Figure 2 shows the analysis results. The path coefficient from PUTS to supervisor revenge was non-significant (β = 0.11, p > .05) and the coefficients from supervisor revenge to job performance (β = −0.02, p > .05), cooperative behavior (β = 0.00, p > .05), and proactive behavior (β = 0.06, p > .05) were non-significant. Thus, H1 and H3 were not supported. The path coefficient from PUTS to supervisor forgiveness was significant (β = −0.24, p < .01) and the coefficients from supervisor forgiveness to job performance (β = 0.28, p < .01), cooperative behavior (β = 0.12, p < .05), and proactive behavior (β = 0.35, p < .01) were significant. Thus, H2 and H4 were supported.

Table 3 shows the mediation analysis. The results indicated that supervisor revenge did not mediate the relationship between outcomes (indirect effects = 0.00–0.01, p > .05). Thus, H5 was not supported. However, the results indicated that supervisor forgiveness significantly mediated the relationship between PUTS and job performance (indirect effect = −0.08, p = .01) and between PUTS and proactive behavior (indirect effect = −0.10, p = .01). Thus, H6 was partially supported.

Figure 2 shows that supervisor affective commitment significantly moderated the relationship between PUTS and supervisor revenge (β = 0.33, p < .05). Figure 3 shows the moderation effect: PUTS was positively associated with supervisor revenge when commitment was high and negatively associated with supervisor revenge when commitment was low. Thus, H7 was supported.

Discussion

This study proposed that supervisors might experience being unfairly treated by their subordinates. The results showed that PUTS did not lead supervisors to revenge but did decrease supervisor forgiveness. Ultimately, PUTS also decreased employee effectiveness via its negative impact on supervisor forgiveness. The results further indicated that PUTS did not cause supervisor revenge and that revenge had no significant effects on outcomes. The moderation analysis demonstrated that supervisor affective commitment tended to make the supervisor stress the unity of the workgroup and make them more likely to act in a revengeful manner in response to PUTS.

This study demonstrates that PUTS is a valid construct and that supervisors do react to PUTS. It suggests that in law enforcement organizations, supervisors would be less likely to take revenge in response to their subordinates’ unfair treatment but more likely to show a decrease in forgiveness to their subordinates. Contrary to our expectations, PUTS did not predict supervisor revenge. We offer three possible explanations for this finding. First, police officers are expected to respond with kindness and benevolence toward others, even in unfair situations (Tyler, 2011; Tyler & Huo, 2002), and as supervisors bear the role of modeling this behavior (Van Craen & Skogan, 2017) they might suppress their revenge reactions. Second, Chinese culture emphasizes the benevolence of leaders toward their subordinates (Farh & Cheng, 2000; Jiang & Cheng, 2008), and supervisors embedded in this culture might therefore be reluctant to use revenge to get even. Third, organizations might prohibit supervisors’ revengeful behavior, and supervisors have the option of under-rating subordinates in performance appraisals without showing revenge. However, supervisors who are highly committed to the organization might believe their acts are benefiting the company, like a soldier for the company, and thus be more inclined to control the behavior of a wrongdoer in the workgroup (Fehr & Gachter, 2002; Organ, 1988; Wenzel et al., 2008).

As predicted, PUTS decreased supervisor forgiveness, which promoted subordinates’ job performance, cooperative behavior, and proactive behavior. The finding that supervisor forgiveness was critical to employee effectiveness is consistent with the results of Fehr and Gelfand (2012). Supervisor forgiveness can significantly impact a workgroup’s forgiving climate, and a recent study indicated that a forgiving climate promoted subordinates’ forgiving behavior with benefits for job performance (Radulovic et al., 2019).

Surprisingly, supervisor revenge did not predict employee effectiveness, although studies have shown that police officers who are not treated fairly and respectfully will respond negatively (Maria et al., 2018; Reynolds et al., 2018). Silin (1976) found that employees showed loyalty to the authoritarian leader in a Chinese family enterprise. Jiang and Cheng’s (2008) study indicated that subordinates felt they should behave loyally to their supervisors in a Chinese organization, even though they might not treat them fairly. These results suggest that a culture of loyalty might prevent subordinates from reacting to revenge by their supervisors, and this might not be the case in other cultural contexts. Further studies are needed to investigate why supervisor revenge did not harm subordinates’ performance.

From the perspective of supervisors, this study explored the responses they exhibit when subjected to unfair treatment from their subordinates. However, the way subordinates treat their supervisors may also be influenced by the supervisors’ behavior (Mitchell & Ambrose, 2007). When supervisors treat their subordinates disrespectfully or unfairly, subordinates might respond in kind (Van Craen & Skogan, 2017). Although future research could further explore this reciprocal relationship, supervisors are more likely than subordinates to seek to restore a sense of fairness when subjected to unfair treatment (Aquino et al., 2006). More importantly, the responses of supervisors are likely to have a more direct impact on subordinates than the reverse.

Policy Implications

Police officers bear responsibilities and experience pressure from multiple sources, including work tasks, public demands, and the need for crime prevention. Consequently, the mental and physical well-being and stress management of police officers are always been a critical focus of both research and practice (Bishopp et al., 2019; McCarty & Skogan, 2013). This study highlights that supervisors in law enforcement units can experience unfair treatment from their subordinates, creating further burdens for those already under multifaceted pressures (Martinussen et al., 2007). Therefore, law enforcement agencies should consider providing leadership training for supervisors to enhance their ability to manage and respond to deviant behavior by subordinates (Sadri, 2012). Furthermore, emotional intelligence training is recommended as it can improve supervisors’ skills and capabilities in handling emotional incidents, including managing their own emotions and those of their subordinates (Salovey & Mayer, 1990).

For law enforcement agencies, it may also be necessary to consider reducing the group loyalty effect, which describes the tendency of members with high loyalty to a group to spontaneously punish those who are disloyal (Fehr & Gächter, 2002). The results of the present study suggest that when supervisors have a high degree of loyalty to the police department, they are more likely to exhibit retaliatory behaviors when mistreated. However, it seems that such behavior does not improve their subordinates’ work performance, cooperative behavior, or proactive behavior. Therefore, while encouraging supervisors’ commitment and loyalty to the organization, law enforcement agencies should also promote inclusivity by encouraging supervisors to accept different approaches and perspectives (Nembhard & Edmondson, 2006), thereby increasing the positive participation of members with diverse characteristics and reducing the potential group loyalty effect.

Limitations and Future Studies

This study applied a group-based dyadic sample, which allowed us to control for common group effects and thus minimize potential common method variance (CMV; Podsakoff et al., 2003). However, a survey study has a limited ability to examine causal relationship, and longitudinal and experimental studies are required to further examine causality. Future studies could also investigate critical moderators in the relationship between PUTS and supervisor forgiveness and revenge and between supervisor revenge and forgiveness and outcomes. Among the supervisor participants, 55% were first-line supervisors and 45% were mid-level supervisors. Although this study did not address the potential influence of supervisor rank, it is plausible that the more powerful mid-level supervisors may be more inclined than first-level supervisors to exhibit retaliatory behaviors (Aquino et al., 2006). Further investigations with attention to supervisor rank could yield insightful findings.

As the law enforcement culture might influence how police officers perceive and react to interpersonal conflicts and managerial issues, it would be interesting to further investigate the relationship between organizational culture and justice-related behavior within law enforcement organizations (Game & Crawshaw, 2017). People normally expect law enforcement organizations should adhere to higher justice standards than business enterprises. This study’s results showed that police officers are conservative in enacting revenge. The self-control of those in managerial roles might be the critical element in managing justice and police officers’ misconduct in police departments (Donner & Jennings, 2014; Restubog et al., 2012; Wolfe et al., 2018). Chinese cultural values, such as harmony (Westwood, 1997), might make supervisors in Taiwanese law enforcement organizations hesitate to engage in acts of revenge and more inclined to demonstrate benevolence and forgiveness. Therefore, similar investigations are needed in Western societies to examine the potential influence of cultural values. Compared with law enforcement organizations, the power distance between supervisors and subordinates in private business organizations tends to be lower and more flexible, with higher personnel turnover (Engelson, 1999; Shavell, 1993). As a result, supervisors in business settings may be more inclined to engage in retaliatory actions to exclude non-conforming or disliked subordinates. Further exploration of how supervisors in business organizations respond to unfair treatment from subordinates could provide valuable insights into these dynamics.

References

Adams, J. S. (1965). Inequity in social exchange. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 267–299). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60108-2

Aquino, K., Tripp, T. M., & Bies, R. J. (2006). Getting even or moving on? Power, procedural justice, and types of offense as predictors of revenge, forgiveness, reconciliation, and avoidance in organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology,91(3), 653–668. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.3.653

Bies, R. J., Tripp, T. M., & Kramer, R. M. (1997). At the breaking point: Cognitive and social dynamics of revenge in organizations. In R. A. Giacalone, & J. Greenberg (Eds.), Antisocial behavior in organizations (pp. 18–36). Sage.

Bishopp, S. A., Worrall, J. L., & Piquero, A. R. (2019). General strain and police misconduct: The role of organizational influence. Crime & Delinquency,65(1), 3–27. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-10-2015-0122

Blau, P. M. (1964). Justice in social exchange. Sociological Inquiry,34(2), 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-682X.1964.tb00583.x

Bradfield, M., & Aquino, K. (1999). The effects of blame attributions and offender likableness on forgiveness and revenge in the workplace. Journal of Management,25(5), 607–631. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639902500501

Bradford, B., & Quinton, P. (2014). Self-legitimacy, police culture and support for democratic policing in an English constabulary. British Journal of Criminology,54(6), 1023–1046. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azu053

Brislin, R. W. (1986). The wording and translation of research instruments. In W. J. Lonner, & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Field methods in cross-cultural research (pp. 137–164). Sage.

Cheng, B. S. (1995). Chaxuegeju and Chinese organizational behavior. Indigenous Psychological Research in Chinese Societies,3, 142–219. https://doi.org/10.6254/1995.3.142. (In Chinese).

Cheng, B. S., Chou, L. F., Wu, T. Y., Huang, M. P., & Farh, J. L. (2004). Paternalistic leadership and subordinate responses: Establishing a leadership model in Chinese organizations. Asian Journal of Social Psychology,7(1), 89–117. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-839X.2004.00137.x

Cheng, B. S., Jiang, D. Y., & Riley, J. H. (2003). Organizational commitment, supervisory commitment, and employee outcomes in the Chinese context: Proximal hypothesis or global hypothesis? Journal of Organizational Behavior,24(3), 313–334. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.190

Cheng, C. Y., Jiang, D. Y., Cheng, B. S., Riley, J. H., & Jen, C. K. (2015). When do subordinates commit to their supervisors? Different effects of perceived supervisor integrity and support on Chinese and American employees. The Leadership Quarterly,26(1), 81–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2014.08.002

Cohen-Charash, Y., & Spector, P. E. (2001). The role of justice in organizations: A meta-analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes,86(2), 278–321. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.2001.2958

Colquitt, J. A., Conlon, D. E., Wesson, M. J., Porter, C. O., & Ng, K. Y. (2001). Justice at the millennium: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research. Journal of Applied Psychology,86(3), 425–445. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.425

Cropanzano, R., Bowen, D. E., & Gilliland, S. W. (2007). The management of organizational justice. The Academy of Management Perspectives,21(4), 34–48. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMP.2007.27895338

Donner, C. M., & Jennings, W. G. (2014). Low self-control and police deviance: Applying Gottfredson and Hirschi’s general theory to officer misconduct. Police Quarterly,17(3), 203–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098611114535217

Elangovan, A. R., & Shapiro, D. L. (1998). Betrayal of trust in organizations. Academy of Management Review,23(3), 547–566. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1998.926626

Engelson, W. (1999). The organizational values of law enforcement agencies: The impact of field training officers in the socialization of police recruits to law enforcement organizations. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology,14, 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02830064E

Exline, J. J., Worthington, E. L., Jr., Hill, P., & McCullough, M. E. (2003). Forgiveness and justice: A research agenda for social and personality psychology. Personality and Social Psychology Review,7(4), 337–348. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0704_06

Farh, J. L., & Cheng, B. S. (2000). A cultural analysis of paternalistic leadership in Chinese organizations. In J. T. Li, A. S. Tsui, & E. Weldon (Eds.), Management and organizations in the Chinese context (pp. 84–127). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230511590_5

Farh, J. L., & Cheng, B. S. (1997). Modesty bias in self-ratings in Taiwan: Impact of item wording, modesty value, and self-esteem. Chinese Journal of Psychology,39, 103–118. (In Chinese).

Fehr, E., & Gächter, S. (2002). Altruistic punishment in humans. Nature,415(6868), 137–140. https://doi.org/10.1038/415137a

Fehr, R., & Gelfand, M. J. (2012). The forgiving organization: A multilevel model of forgiveness at work. The Academy of Management Review,37(4), 664–688. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2010.0497

Fischer, R., Ferreira, M. C., Jiang, D. Y., Cheng, B. S., Achoui, M. M., Wong, C. C., et al. (2011). Are perceptions of organizational justice universal? An exploration of measurement invariance across thirteen cultures. Social Justice Research,24(4), 297–313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-011-0142-7

Game, A., & Crawshaw, J. (2017). A question of fit: Cultural and individual differences in interpersonal justice perceptions. Journal of Business Ethics,144(2), 279–291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2824-9

Goodstein, J., & Butterfield, K. D. (2010). Extending the horizon of business ethics: Restorative justice and the aftermath of unethical behavior. Business Ethics Quarterly,20(3), 453–480.

Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. The Leadership Quarterly,6(2), 219–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/1048-9843(95)90036-5

Grant, A. M., Parker, S., & Collins, C. (2009). Getting credit for proactive behavior: Supervisor reactions depend on what you value and how you feel. Personnel Psychology,62(1), 31–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2008.01128.x

Greco, L. M., Whitson, J. A., O’Boyle, E. H., Wang, C. S., & Kim, J. (2019). An eye for an eye? A meta-analysis of negative reciprocity in organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology,104(9), 1117–1143. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000396

Greenberg, J. (1987). A taxonomy of organizational justice theories. Academy of Management Review,12(1), 9–22. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1987.4306437

Greenberg, J. (2010). Organizational injustice as an occupational health risk. The Academy of Management Annals,4(1), 205–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520.2010.481174

Grégoire, Y., & Fisher, R. J. (2008). Customer betrayal and retaliation: When your best customers become your worst enemies. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science,36(2), 247–261. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-007-0054-0

Griffin, S. P., & Bernard, T. J. (2003). Angry aggression among police officers. Police Quarterly,6(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098611102250365

Haas, N., Van Craen, M., Skogan, W. G., & Fleitas, D. (2015). Explaining officer compliance: The importance of procedural justice and trust inside a police organization. Criminology & Criminal Justice,15(4), 442–463. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748895814566288

Hodgins, H. S., Liebeskind, E., & Schwartz, W. (1996). Getting out of hot water: Facework in social predicaments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,71(2), 300–314. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.71.2.300

Jiang, D. Y., & Cheng, B. S. (2008). Affect- and role‐based loyalty to supervisors in Chinese organizations. Asian Journal of Social Psychology,11(3), 214–221. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-839X.2008.00260.x

Jiang, D. Y., Cheng, M. Y., Wang, L., & Baranik, L. (2014). Differential leadership: Reconceptualization and measurement development [Paper presentation]. The 29th Annual SIOP Conference, Honolulu, United States.

Kremer, J. F., & Stephens, L. (1983). Attributions and arousal as mediators of mitigation’s effect on retaliation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,45(2), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.45.2.335

Lam, C. K., Spreitzer, G. C., & Fritz, C. (2014). Too much of a good thing: Curvilinear effect of positive affect on proactive behaviors. Journal of Organizational Behavior,35(4), 530–546. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1906

Liu, H., Chiang, J. T., Fehr, R., Xu, M., & Wang, S. (2017). How do leaders react when treated unfairly? Leader narcissism and self-interested behavior in response to unfair treatment. Journal of Applied Psychology,102(11), 1590–1599. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000237

Loi, R., Lai, J. Y. M., & Lam, L. W. (2012). Working under a committed boss: A test of the relationship between supervisors’ and subordinates’ affective commitment. The Leadership Quarterly,23(3), 466–475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.12.001

Maria, A. S., Wörfel, F., Wolter, C., Gusy, B., Rotter, M., Stark, S., et al. (2018). The role of job demands and job resources in the development of emotional exhaustion, depression, and anxiety among police officers. Police Quarterly,21(1), 109–134. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098611117743957

Martinussen, M., Richardsen, A. M., & Burke, R. J. (2007). Job demands, job resources, and burnout among police officers. Journal of Criminal Justice,35(3), 239–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2007.03.001

McCarty, W. P., & Skogan, W. G. (2013). Job-related burnout among civilian and sworn police personnel. Police Quarterly,16(1), 66–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/10986111124573

Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1991). A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review,1(1), 61–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/1053-4822(91)90011-Z

Meyer, J. P., Allen, N. J., & Smith, C. A. (1993). Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. Journal of Applied Psychology,78, 538–551. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.4.538

Mitchell, M. S., & Ambrose, M. L. (2007). Abusive supervision and workplace deviance and the moderating effects of negative reciprocity beliefs. Journal of Applied Psychology,92(4), 1159–1168. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.4.1159

Nembhard, I. M., & Edmondson, A. C. (2006). Making it safe: The effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. Journal of Organizational Behavior,27(7), 941–966. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.413

Niehoff, B. P., & Moorman, R. H. (1993). Justice as a mediator of the relationship between methods of monitoring and organizational citizenship behavior. Academy of Management Journal,36(3), 527–556. https://doi.org/10.2307/256591

O’Reilly, C. A., & Chatman, J. (1986). Organizational commitment and psychological attachment: The effects of compliance, identification, and internalization on prosocial behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology,71(3), 492–499. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.492

Organ, D. W. (1988). Organizational citizenship behavior: The good soldier syndrome. Lexington Books.

Owens, B. P., Baker, W. E., Sumpter, D. M., & Cameron, K. S. (2016). Relational energy at work: Implications for job engagement and job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology,101(1), 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000032

Paoline, I. I. I., & Gau, J. M. (2020). An empirical assessment of the sources of police job satisfaction. Police Quarterly,23(1), 55–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098611119875117

Parker, S. K., Williams, H. M., & Turner, N. (2006). Modeling the antecedents of proactive behavior at work. Journal of Applied Psychology,91(3), 636–652. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.3.636

Pearson, C. M., & Porath, C. L. (2005). On the nature, consequences, and remedies of workplace incivility: No time for nice? Think again. Academy of Management Perspectives,19(1), 7–18. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.2005.15841946

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Bommer, W. H. (1996). Meta-analysis of the relationships between Kerr and Jermier’s substitutes for leadership and employee job attitudes, role perceptions, and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology,81(4), 380–399. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.81.4.380

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology,88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Priesemuth, M., Schminke, M., Ambrose, M. L., & Folger, R. (2014). Abusive supervision climate: A multiple-mediation model of its impact on group outcomes. Academy of Management Journal,57(5), 1513–1534. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0237

Qin, X., Huang, M., Johnson, R. E., Hu, Q., & Ju, D. (2018). The short-lived benefits of abusive supervisory behavior for actors: An investigation of recovery and work engagement. Academy of Management Journal, 61(5), 1951–1975. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.1325

Radulovic, A. B., Thomas, G., Epitropaki, O., & Legood, A. (2019). Forgiveness in leader-member exchange relationships: Mediating and moderating mechanisms. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 92(3), 498–534. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12274

Restubog, S. L. D., Zagenczyk, T. J., Bordia, P., Bordia, S., & Chapman, G. J. (2012). If you wrong us, shall we not revenge? Moderating roles of self-control and perceived aggressive work culture in predicting responses to psychological contract breach. Journal of Management, 41(4), 1132–1154. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206312443557

Reynolds, P. D., Fitzgerald, B. A., & Hicks, J. (2018). The expendables: A qualitative study of police officers’ responses to organizational injustice. Police Quarterly, 25(1), 3–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098611117731558

Rothstein, B., & Stolle, D. (2008). The state and social capital: An institutional theory of generalized trust. Comparative Politics,40(4), 441–459. https://doi.org/10.5129/001041508X12911362383354

Sadri, G. (2012). Emotional intelligence and leadership development. Public Personnel Management,41(3), 535–548. https://doi.org/10.1177/009102601204100308

Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional intelligence. Imagination, cognition and personality,9(3), 185–211. https://doi.org/10.2190/DUGG-P24E-52WK-6CDG

Sayles, S., & Albritton, J. (1999). Is there a distinct subculture in policing? In J. Sewell (Ed.), Controversial issues in policing (pp. 154–171). Allyn & Bacon.

Shavell, S. (1993). The optimal structure of law enforcement. The Journal of Law and Economics,36(1), 255–287.

Silin, R. H. (1976). Leadership and values: The organization of large-scale Taiwanese enterprises. Harvard University, East Asian Research Center.

Strelan, P., Feather, N. T., & McKee, I. (2008). Justice and forgiveness: Experimental evidence for compatibility. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology,44(6), 1538–1544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2008.07.014

Stuckless, N., & Goranson, R. (1992). The vengeance scale: Development of a measure of attitudes toward revenge. Journal of Social Behavior & Personality,7(1), 25–42.

Tepper, B. J. (2000). Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal,43(2), 178–190. https://doi.org/10.2307/1556375

Tepper, B. J., Duffy, M. K., Henle, C. A., & Lambert, L. S. (2006). Procedural injustice, victim precipitation, and abusive supervision. Personnel Psychology,59(1), 101–123. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2006.00725.x

Trinkner, R., & Cohn, E. S. (2014). Putting the social back in legal socialization: Procedural justice, legitimacy, and cynicism in legal and nonlegal authorities. Law and Human Behavior,38(6), 602–617. https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000107

Trinkner, R., Jackson, J., & Tyler, T. R. (2018). Bounded authority: Expanding appropriate police behavior beyond procedural justice. Law and Human Behavior,42(3), 280–293. https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000285

Tripp, T. M., & Bies, R. J. (2009). Getting even: The truth about workplace revenge and how to stop it. Wiley.

Tripp, T. M., Bies, R. J., & Aquino, K. (2007). A vigilante model of justice: Revenge, reconciliation, forgiveness, and avoidance. Social Justice Research,20(1), 10–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-007-0030-3

Tyler, T. R. (2011). Why do people cooperate? The role of social motivations. Princeton University.

Tyler, T. R., & Blader, S. L. (2013). Cooperation in groups: Procedural justice, social identity, and behavioral engagement. Psychology Press.

Tyler, T. R., & Blader, S. L. (2001). Identity and cooperative behavior in groups. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations,4, 207–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430201004003003

Tyler, T. R., & Blader, S. L. (2003). The group engagement model: Procedural justice, social identity, and cooperative behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Review,7(4), 349–361. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0704_07

Tyler, T. R., & Huo, Y. J. (2002). rust in the law. Encouraging public cooperation with the police and courts. Russell Sage Foundation.

Van Craen, M., & Skogan, W. G. (2017). Achieving fairness in policing: The link between internal and external procedural justice. Police Quarterly,20(1), 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098611116657818

Van Dyne, L., & LePine, J. A. (1998). Helping and voice extra-role behaviors: Evidence of construct and predictive validity. Academy of Management Journal,41(1), 108–119. https://doi.org/10.2307/256902

Wenzel, M., Okimoto, T. G., Feather, N. T., & Platow, M. J. (2008). Retributive and restorative justice. Law and Human Behavior,32(5), 375–389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10979-007-9116-6

Westwood, R. (1997). Harmony and patriarchy: The cultural basis for paternalistic headship among the overseas Chinese. Organization Studies,18(3), 445–480. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840697018003

Witvliet, C. V., Ludwig, T. E., & Bauer, D. J. (2002). Please forgive me: Transgressors’ emotions and physiology during imagery of seeking forgiveness and victim responses. Journal of Psychology and Christianity,21(3), 219–233.

Wolfe, S. E., Nix, J., & Campbell, B. A. (2018). Police managers’ self-control and support for organizational justice. Law and Human Behavior,42(1), 71–82. https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000273

Wu, T. Y., Hu, C., & Jiang, D. Y. (2012). Is subordinate’s loyalty a precondition of supervisor’s benevolent leadership? The moderating effects of supervisor’s altruistic personality and perceived organizational support. Asian Journal of Social Psychology,15(3), 145–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-839X.2012.01376.x

Yukl, G. A. (2002). Leadership in Organizations (5th ed.). Prentice Hall.

Zhang, Y., LePine, J. A., Buckman, B. R., & Wei, F. (2014). It’s not fair … or is it? The role of justice and leadership in explaining work stressor-job performance relationships. Academy of Management Journal,57(3), 675–697. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.1110

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by MOST grant 110-2410-H194-065-SS2 from the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan, ROC. We would like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their constructive suggestions.

Professional English language editing support provided by AsiaEdit (asiaedit.com).

Funding

This work was funded by Taiwan National Science and Technology Council (MOST 110-2410-H-194 -065 -SS2).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This research has been conducted with full compliance with journal ethical standards. This manuscript and data have not been previously published nor are under consideration for publication elsewhere. There are no relevant financial or non-financial competing interests to report.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Perceived Unfair Treatment by a Subordinate (PUTS)

-

1.

This subordinate consults with me before making major work decisions. (reversed coded)

-

2.

When assigning tasks to this subordinate, he/she is considerate of my position as a supervisor. (reversed coded)

-

3.

When assigning tasks to this subordinate, he/she shows a respectful attitude towards me. (reversed coded)

-

4.

When this subordinate reports difficulties with work tasks to me, he/she is honest and transparent without deception. (reversed coded)

-

5.

I feel this subordinate is not honest with me.

-

6.

I feel betrayed by this subordinate.

-

7.

I feel this subordinate is trying to take advantage of me in every way possible.

-

8.

This subordinate considers the negative impact on me when making decisions.

-

9.

When this subordinate refuses to execute assigned tasks, he/she provides me with reasonable explanations. (reversed coded)

-

10.

This subordinate does not deliberately ignore my opinions when making work decisions.

-

11.

I feel deceived by this subordinate.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, DY., Chen, TH. & Huang, CJ. Perceived Unfair Treatments by the Subordinate: Its Association with the Effectiveness of Subordinates and the Mediating Role of Supervisory Forgiveness and Revenge. Asian J Criminol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-024-09440-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-024-09440-2