Abstract

Studies on confidence in the police have employed three theoretical frameworks: (1) an instrumental model that focuses on the effect of police effectiveness and fear of crime, (2) an expressive model that emphasizes the role of general perception on social cohesion, and (3) a procedural model that highlights the distinct role of perceived police fairness. While studies have clarified specific pathways in the instrumental and expressive models, a comprehensive examination of all three models remains sparse in the field of criminal justice. Furthermore, existing studies rarely examined the multilevel causal structures of these models. This study aims to address these limitations by examining separate and comprehensive multilevel structural equation models (SEMs) of these theoretical frameworks. The data was collected through the multistage stratified random sampling from 12 boroughs of four metropolitan cities in South Korea, and a total of 2040 individuals were interviewed face-to-face. The results of the SEM analyses showed that perceived police fairness was the primary determinant of confidence in the police in South Korea, while fear of crime, perceived police effectiveness, and perceived social cohesion had a limited effect. Policy implications and suggestions for future studies are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Public confidence in the police is a critical determinant of successful policing (Bradford & Myhill, 2015; Cao, Frank, & Cullen, 1996; Jackson & Bradford, 2009; Jang & Hwang, 2014; Merry, Power, McManus, & Alison, 2012; Rusinko, Johnson, & Hornung, 1978; Sindall & Sturgis, 2013; Skogan, 2009). A higher level of confidence in the police tended to increase calls for service and support for the police, and in turn, reduces fear of crime, antisocial behaviors, perceived crimes, and risk of victimization (Bahn, 1974; Povey, 2001; Quinton & Morris, 2008; Skogan, 2009). Within the context of community policing, high confidence in the police tends to promote healthy partnerships between communities and the police and helps reduce disorders and crimes (Jang & Hwang, 2014; Reisig & Parks, 2000). In Britain, the Home Office linked confidence in the police to the overall effectiveness of their criminal justice system and initiated the National Reassurance Police Programme, which highlighted the critical role of public’s confidence in police effectiveness (Povey, 2001; Quinton & Morris, 2008; Skogan, 2009).

Given its importance, scholars, policymakers, and practitioners have increasingly paid attention to diverse factors associated with confidence in the police. Among the various analytic models used to assess these factors, they largely fall into three theoretical frameworks: instrumental (or accountability) model, expressive model, and procedural model (Bradford & Myhill, 2015; Jackson & Bradford, 2009; Jackson, Bradford, Hohl, & Farrall, 2009; Jang & Hwang, 2014; Merry et al., 2012). The instrumental model hypothesizes that people believe that the police are responsible for local crimes and disorder; therefore, their confidence in the police is driven by their victimizations, neighborhood crime rate, and fear of crime (Skogan, 2009). The expressive model is based on the neo-Durkheimian theory and posits that public confidence in the police is determined by individuals’ perception about broader and symbolic notions of social cohesion, order, and formal or informal social control (Bradford & Myhill, 2015; Jackson, 2004; Jackson & Bradford, 2009; Loader, 1997). Lastly, the procedural model postulates that legitimacy, justice, and fairness in policing are keys to understanding the level of public confidence in the police (Bradford, Jackson, & Stanko, 2009; Merry et al., 2012; Tyler, 1988; Tyler & Huo, 2002).

While these theoretical frameworks have advanced the clarification of complex causal paths to confidence in the police, there have been two noteworthy limitations in previous studies. First, there have been a handful of studies clarifying the comprehensive effects of these three frameworks. Recently, a few studies have extensively examined these frameworks and clarified the effects of the core determinants of police confidence (i.e., Holmes, Painter II, & Smilth, 2017; Jang & Hwang, 2014). For example, Jang and Hwang (2014) examined the relative effects of instrumental and expressive models and found that the expressive model retained a greater effect on confidence than the instrumental model did. However, these studies were still limited in addressing the impact of the procedural model. Secondly, these theoretical models encompass multilevel implications signifying individual perception and macro-level status (see Boateng, 2016; Holmes et al., 2017). Especially, instrumental and expressive models postulate the effects of neighborhood or societal conditions in their theoretical frameworks. Few studies, however, have clarified whether these macro-level factors have a direct or mediating effect on individuals’ confidence (i.e., neighborhood crime rate influences individual fear of crime, which in turn impacts his/her confidence in the police).

The primary purpose of this study is to fill the void by examining these three theoretical frameworks in both distinctive and comprehensive ways and constructing multilevel structural equation models (SEMs) that examine the direct and indirect effects of macro-level variables. A total of 2040 individuals were surveyed through the multistage random sampling process in four major metropolitan areas in South Korea. As public confidence in the police is a serious concern in South Korea (Batzeveg, Hwang, & Han, 2017; Boateng, Lee, & Abess, 2016; Jang & Hwang, 2014), findings from this study should provide valuable policy implications regarding public’s confidence in the police to Korean criminal justice policymakers.

Public Confidence in the Police in South Korea

The contemporary history of South Korea is marked with several distinctive political and social periods which had a profound impact on policing and its public perceptions including (1) the Imperial Japanese occupation (1910 to 1945), (2) the Korean War (1950–1953), (3) era of military rules (1961–1993), and (4) the current democratic republic with several presidencies tarnished with corruption and scandals (1993 to the present). During each of these regimes, the Korean police, a centralized police force following a top-down command structure, have been used as a political tool by the central government to serve the interests of the political elite (Kwak & McNeeley, 2019; Nalla & Hwang, 2006).

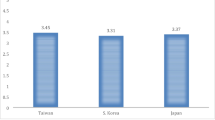

During the Japanese occupation, for example, the police were used to perform surveillance on the Korean people, suppress anti-Japanese sentiment, and oppress dissents brutally and violently. The unbounded police power infiltrated every aspect of Korean people’s lives, contributing to the public’s deep antagonism and distrust of the police (Pyo, 2001). The Korean War heavily involved the police in the military operations, forging a police image as an agent of the governmental bureaucracy (Hwang, McGarrell, & Benson, 2005). The subsequent era of dictatorial and authoritative military rules made the police intensely involved in the politics of military personnel. The police were charged with suppressing freedom of expression and association, arresting political dissents and sending them to reeducation camps, interfering with elections, and cleansing gang members, drug users, and violent offenders from the street with brutal and unfair tactics, while the police themselves maintained corruptive connections to criminals (see Boateng et al., 2016; B. Moon, 2004 for detailed examples). These heavy-handed crime control tactics brewed the Korean public’s deep hostility, suspicion, and disrespect toward the police, thus challenging its legitimacy and authority (Han & Bu, 2000; Hoffman, 1982; Joo, 2003; S. Lee, 1990; B. Moon, 2004; B. Moon & Zager, 2007; C. Moon & Kim, 1996; Nalla & Hwang, 2006; Pyo, 2001). Even after 1993, when South Korea embarked on modern democracy, corruption and political scandals continued to taint presidencies resulting in resignations, arrests, and suicide of several presidents. Korean citizens thus remained largely cynical and suspicious about their political system and the police as an agent of social control, as demonstrated by the relatively low public’s confidence in the police, particularly when compared with Taiwan, Japan, and the USA (Boateng et al., 2016; Cao & Dai, 2006; Jang & Hwang, 2014).

To address their identity crisis and modernize their organization, South Korea police initiated Police Grand Reform in 1999 to transform its police force from political-oriented to citizen-oriented policing. The reform called for enhancing police legitimacy and accountability through creating an independent civilian organization free from governmental interference, the National Police Board, which would be in charge of internal police affairs such as promotions, budgets, and investigations of police misconduct (S. Lee, 1990; B. Moon, 2004). It also aimed at increasing awareness and knowledge of the rule of law, criminal procedure, human rights, and the importance of police-community relations through hiring college graduates and its intensive 8-month police academy for new police recruits (B. Moon & Maorash, 2008; Pyo, 2002; Roh & Choo, 2007). Finally, the reform restructured the police organization and operational strategies by centralizing motor patrol and criminal investigation in urban communities, which allows front-line police officers to focus on building a police-community relationship and providing services to local residents (e.g., receiving complaints, providing information and advice, foot/bicycle patrol, organizing community prevention, and developing personal contacts) (Jang & Hwang, 2014; Pyo, 2002).

Empirical studies have consistently reported that public confidence in the police is relatively low in South Korea (Cao, Lai, & Zhao, 2012; Hwang et al., 2005; Jang & Hwang, 2014). Analyzing the data from the sixth-round World Values Surveys, we have identified the temporal change of average Korean public confidence in the police, along with that of Japan, the USA, and world average for comparison purposes, from 1983 to 2013 and present in Fig. 1. Overall, this explorative analysis shows that public confidence in the police in Korea is generally lower than that of Japan, the USA, and the world average in some years. The public’s confidence suffered a steep drop during the 1980s and 1990s but climbed up since the 2000s in South Korea. While the decline of confidence in the police can be explained by various political and social events such as the historical legacy of the Japanese colonial rule, the authoritarian military regime, and the corruption scandals, the upward trajectory in recent years seems to coincide with the implementation of the Police Grand Reform, aiming at transforming the police from the political orientation to citizen orientation, albeit that there is much room for improvement (Boateng et al., 2016; Jang & Hwang, 2014; Roh & Choo, 2007).

Theoretical Framework

In this section, we will first review the details of instrumental, expressive, and procedural models and then propose corresponding SEMs which portray their theoretical frameworks in shaping public confidence in the police.

Instrumental Model

The instrumental model theorizes that people expect the police to serve particular roles and functions in society, and their confidence in the police is closely associated with their perceived police effectiveness in achieving these goals. As the primary agency of law enforcement, the police are charged with suppressing crime, maintaining order, and reducing fear of crime. Thus, they should be evaluated based on their performance in these areas. Research from the instrumental perspective has explored four core determinants of public confidence in the police such as (1) fear of crime, (2) perceived effectiveness of the police, (3) official crime rate, and (4) victimization experience.

Studies focusing on fear of crime argued that criminogenic neighborhood conditions cause residents to worry about victimization and attribute these undesirable conditions to the inability or unwillingness of the police to handle criminal problems (Ren, Cao, Lovrich, & Gaffney, 2005; Skogan, 2009; Xu, Fiedler, & Flaming, 2005). Accordingly, these studies suggested that a higher-level fear of crime could inflame cynicism toward the police, thus negatively impacting confidence in the police (Ren et al., 2005; Skogan, 2009). Similarly, studies also asserted that police effectiveness played an essential role in shaping police legitimacy (Cao & Wu, 2019; Garcia & Cao, 2005; Taylor & Lawton, 2012), and in turn, police legitimacy facilitated the public acceptance of police actions and confidence in the police (Tyler, 2006; Tyler & Huo, 2002).

At a macro level, a series of studies found that crime rate was a good indicator of police effectiveness and public confidence in the police (Cao et al., 2012; Jang, Joo, & Zhao, 2010; Reisig & Parks, 2000; Skogan, 2009). In their SEM analysis of two-wave survey data in Phoenix, AZ, Baker et al. (1983) found that a sudden increase of reported crime (crime wave) significantly increased the level of fear of crime and decreased public’s confidence in the police. Reisig and Parks (2000) found that residents of neighborhoods with a higher homicide rate retained a lower level of satisfaction with the police. Other studies also presented that criminal problems such as violent crimes, drug dealings, and gang activities in the neighborhood inversely influence residents’ confidence in the police (Jesilow, Meyer, & Namazzi, 1995; Weitzer & Tuch, 2002; Weitzer, Tuch, & Skogan, 2008). Due to the multilevel trait of crime rate, Reisig and Parks (2000) differentiated this approach as the neighborhood context model compared with the quality of life model focusing on individuals’ perception of criminal conditions. Victimization experience seemed to have a mixed impact on confidence in the police. While some studies found a significant impact of victimization experience on attitude toward the police (Baker et al., 1983; Dowler & Sparks, 2008; Jackson et al., 2009), other studies suggested a non-significant correlation between the two variables (Hawdon & Ryan, 2003; Smith & Hwawkins, 1973).

The current study builds on the previous research findings and constructs the instrumental model of confidence in the police using a multilevel SEM, as shown in Fig. 2. In this model, perceived police effectiveness, the core factor of the instrumental model, is hypothesized to have a direct impact on confidence in the police, while individual victimization experience and fear of crime influence his/her confidence in the police directly and indirectly. At the macro level, crime rate is hypothesized to cause the variation of individual fear of crime, perceived police effectiveness, and confidence in the police.

Expressive Model

The expressive model postulates that the police embody order, justice, and social stability; therefore, people expect the police to defend broader structures of social order and represent the symbolic notion of social cohesion (Jackson, 2004; Jackson & Bradford, 2009; Jackson et al., 2009; Jackson & Sunshine, 2007; Jang & Hwang, 2014; Loader, 1997; Loader & Mulcahy, 2003; Taylor & Lawton, 2012). According to this perspective, the police are a highly visible institution of state power which handles concerns about social order and social problems; correspondingly, public confidence in the police is primarily determined by individuals’ general perception of social cohesion and the strength of formal and informal social controls (Jackson & Bradford, 2009; Jackson et al., 2009). Theoretically, this model bases its origin on the neo-Durkheimian approach initiated by Jackson and Sunshine (2007). The neo-Durkheimian theory argues that a sense of social order and cohesiveness is the essential identity of the police, and people grant the police as guardians of social order and representatives of the community (Jackson & Sunshine, 2007; Sunshine & Tyler, 2003). When social norms and values fade, therefore, people expect the police to reinstate a healthy social environment and reestablish social orders (Jackson & Bradford, 2009).

Accordingly, the expressive model presents individuals’ assessment of social cohesion, control, and the degree of breakdown and fragmentation of society as the critical determinant of confidence in the police (Jackson & Bradford, 2009; Jang & Hwang, 2014). Empirical examinations of these variables in previous studies have revealed that social cohesion and perceived informal social control significantly influence individual confidence in the police (Jackson & Bradford, 2009; Jackson et al., 2009; Jang & Hwang, 2014). Besides these variables, studies examining this model have introduced the level of deprivation as a determinant of social order and confidence in the police (Jackson et al., 2009).

Building upon these existing research findings, the current study delineates the expressive model, as illustrated in Fig. 3. At the micro level, individuals’ perceptions regarding four structural factors—perceived social cohesion, perceived collective efficacy, perceived informal control, and perceived formal control—are hypothesized to affect confidence in the police directly. As neo-Durkheimian theory asserts, perceived social cohesion accounts for the individual difference in the other three factors. At the macro level, the level of deprivation is hypothesized to influence both perceived social cohesion and confidence in the police.

Procedural Model

The procedural model has suggested that the perceived fairness of police should significantly affect citizens’ satisfaction with police-initiated contact (Bradford et al., 2009; Merry et al., 2012), and their confidence in the police (Bradford et al., 2009; Cao & Wu, 2019; Tyler, 1988, 2006; Tyler & Huo, 2002). Several studies examining the expressive model also pointed out the importance of police fairness in their analyses (i.e., Jackson et al., 2009).

The effect of police fairness has been discussed under the framework of procedural justice, which incorporates normative perspectives. Contrary to the instrumental perspective, which emphasizes the role of police performance and distributive justice (Sunshine & Tyler, 2003), the normative perspective suggested a multidimensional judgment of procedural justice, including legitimacy, ethicality, representation, consistency, neutrality, and error correction (Tyler, 2006). Through empirical research, Tyler and his associates found that when citizens felt they were being treated fairly, they tended to regard police authority as legitimate, thus were more likely to comply and have more favorable opinions about the police (Tyler, 2003, 2006; Tyler & Huo, 2002). Moreover, when citizens viewed the police exercising their authority in a fair manner (e.g., the police listened to their complaints/opinions) and having the right motives (e.g., being neutral and ethical), they were more likely to trust the police and respect their authority (Lind & Tyler, 1988). Overall, studies in Western countries have generated ample evidence positively linking procedural justice with public confidence in the police, including police encounter with ethnic minorities (Jackson et al., 2009; Merry et al., 2012; Tyler, 1988, 2006; Tyler & Huo, 2002).

The significance of police fairness is also highlighted in the studies of police-citizen contact. While earlier studies on police-citizen contact found that it negatively influenced confidence in the police, follow-up studies identified that diverse situational factors (i.e., fairness in police operations) altered citizens’ attitude to the police (Bartsch & Cheurprakobkit, 2004; Bradford & Myhill, 2015; Merry et al., 2012; Rusinko et al., 1978). After examining these situational factors, Bradford and Myhill (2015) concluded that fairness of police contact is the critical determinant of confidence in the police. Studies on racial disparities in the level of confidence in the police also have presented that the sense of fairness is an essential underlying mechanism, which links racial discrepancy to confidence in the police (Cao & Wu, 2019).

Constructing from these findings, the current study proposes a procedural model, which hypothesizes that individuals’ victimization should yield police contact and influence their perception of police fairness, and in turn, this perception of police fairness should be the primary determinant of their confidence in the police. Using the SEM approach, we illustrate this model and present in Fig. 4.

Current Study

To identify the core determinants of confidence in the police within the context of South Korea, the current study examines three above-stated models separately and comprehensively in a stepwise manner. We expect that this approach should address the following research questions. First, when analyzed separately and in aggregation, which variables in the three models significantly impact confidence in the police after controlling for participants’ demographics and the other models? Second, which model provides the best model-fit in predicting confidence in the police? Third, is confidence in the police conditioned upon neighborhood socio-economic status and crime rate? These research questions help clarify the dynamic causal paths to public confidence in the police.

Methodology

Data

To examine the given SEMs, we sampled a total of 2040 individuals with multistage random sampling. We first selected four most-populated metropolitan cities out of seven in South Korea. Within the four selected metropolitan cities, there are a total of 50 boroughs, 12 of which were randomly selected for this study. A list of residents of 20 years or older were drawn from the official resident registration records for each of the 12 boroughs, and 170 residents were randomly selected from each list, totaling a sample of 2040 residents for this study.

The door-to-door interviews were conducted between October 20, and November 3, 2017. Trained interviewers were instructed to randomly select another resident in the same or nearby neighborhood if any of the residents were not available or declined being interviewed until the total number of samples was met. An overall comparison between our sample and the national population indicates that our sample is relatively older with an average of 47.1 years of age compared with 40.9 national average, and with slightly more female participants (51% v. 50.01% national rate). These discrepancies could be attributable to our sample selection criteria of excluding individuals under 20 years of age, and the greater availability of females at residence during the day.

Variables

Confidence in the Police

Previous studies measure confidence in the police in various ways including perceived police effectiveness, procedural justice/fairness, satisfaction with the police, willingness to help the police, and reporting crimes to the police (i.e., Cao et al., 1996; Jang & Hwang, 2014; H. D. Lee, Cao, Kim, & Woo, 2019; Sindall & Sturgis, 2013; Taylor & Lawton, 2012). In this study, we asked respondents to answer a direct question that taps their general confidence in the police, “how much do you have confidence in the police?” Respondents are given five Likert-scale choices, including a great deal (5), quite a lot (4), neutral (3), not much (2), and not at all (1). These responses are given the values from 5 to 1 correspondingly, in which the higher value indicates the higher level of confidence in the police.

Victimization

To measure individual criminal victimization experience, we asked respondents whether they were a victim of nine crimes in the past year (1 = yes; 0 = no), including (1) burglary, (2) robbery, (3) pickpocketing, (4) auto theft including bike or motorcycle, (5) assault, (6) extortion, (7) sexual crime, (8) auto damage, and (9) property damage. Then, we count the number of yes for each type of crime and introduce the sum of yes responses as a victimization variable. Therefore, the variable, victimization, indicates the frequency of victimization from various crime types that a respondent has experienced in the past year.

Fear of Crime

Respondents were asked to rate their fear of being victimized for each of the crimes, such as stealing, fraud, burglary, robbery, assault, stalking, and sex crimes. The five Likert-scale choices included never (1), seldom (2), occasionally (3), usually (4), and always (5). The seven responses of each respondent were factorized into a latent variable (α = .928) based on Item Response Theory (IRT)–based confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The IRT-based CFA method is specially devised for factor indicators with multiple ordered categories such as Likert-scale values (Fox, 2010; van der Linden, 2016).

Perceived Police Effectiveness

To measure each respondent’s perception about the effectiveness of the police, we have introduced three questionnaires: what do you think about the following operations of the police in your neighborhood?: (1) doing well on patrolling the neighborhood for crime prevention, (2) immediately responding to a call/notification about criminal incidents, and (3) admittedly arresting criminals if a crime is reported. For each question, respondents are given five Likert-scale response choices such as never (1), seldom (2), occasionally (3), usually (4), and always (5). Each respondent’s responses for three questions are factorized into one latent variable through the IRT-based CFA method (α = .790).

Perceived Social Cohesion

Previous studies have defined social cohesion as the willingness of members in society to cooperate in order to achieve their shared values and goals (Stanley, 2003). Four questions were designed to measure this variable in our study: (1) Do community members interact with one another? (2) Do community members talk about incidents in the neighborhood? (3) Do community members help one another in crisis? and (4) Are community members involved in community meetings and events? Answers to these questions based on the five Likert-scale choices were again factorized into a latent variable through the IRT-based CFA method (α = .836).

Perceived Collective Efficacy

Collective efficacy refers to community members’ active involvement in collaboration for specific goals such as order maintenance and crime prevention (Sampson, Raudenbush, & Earls, 1997). Three items are introduced to measure perceived collective efficacy in this study (α = .631): (1) community members’ willingness to help children who suffer from harassment or bullying in the community, (2) community members’ willingness to call the police when a crime breaks out, and (3) community members’ willingness to participate in community patrols to prevent crimes, based on the five-category Likert scale.

Perceived Informal Control

We elaborate on the definition of informal social control as community members’ informal intervention toward disorderly and criminal behaviors in the neighborhood (Bursik, 1999) and measured perceived informal control with the following six questions: how frequently do you observe the following incidents/behaviors in your neighborhood: (1) garbages on the street and dirty, (2) dark and obscure places, (3) abandoned car or building, (4) disorderly behaviors, (5) delinquent juveniles in a group, and (6) quarreling people on the street. Respondents are given five Likert-scale items such as never (5), seldom (4), occasionally (3), usually (2), and always (1), and their replies have been given values in the opposite direction to make the higher value show the higher degree of informal control (i.e., never = 5). Each respondent’s responses are factorized into one latent variable through the IRT-based CFA method (α = .891).

Perceived Formal Control

To measure individuals’ perception about formal control, we have questioned respondents as to how well do they think the following criminal justice practices perform in society: (1) crime prevention, (2) arresting criminals, (3) supporting and protecting victims, (4) rehabilitating criminals, and (5) publicizing crime prevention efforts. Respondents are given five Likert-scale answer choices, and their answers are factorized into one latent variable through the IRT-based CFA method (α = .838).

Police Fairness

The fairness of police operations is measured by two survey items. The respondents were asked to rate two statements: (1) the police investigate criminal cases in a fair manner regardless of suspects’ or criminals’ social positions, and (2) the operation of the police is not influenced by suspects’ economic status or income level. Respondents are given four options: (1) not fair at all, (2) unlikely to be fair, (3) likely to be fair, and (4) absolutely fair. The responses were factorized into one latent variable through the IRT-based CFA method (α = .913). Table 1 presents the standardized and unstandardized factor scores for all indicators in this study.

Macro-level Variables

Crime rate and deprivation are introduced as macro-level variables. The crime rate of each borough is calculated as the number of property and violent crimes per 1000 residents in the year of 2014,Footnote 1 and the level of deprivation is operationalized as the GINI index in each borough based on Korean Statistical Information Service.Footnote 2

Control Variables

Besides the explanatory variables given in the models, this study introduces five control variables: sex, age, education, marital status, and income. Studies have revealed that older people and females tended to have a relatively more favorable attitude toward the police than their counterparts (Jang et al., 2010; Weitzer & Tuch, 2004). The current study hypothesizes that married people and people with higher education and income levels should have a more positive opinion regarding the police as their perceptions of risks are expected to be higher (Ho & McKean, 2004). Sex (1 = male) and marital status (1 = coupled) are dummy variables, and each respondent’s actual age is used to measure age. Education is operationalized into eight categories from illiterate (= 1) to graduate degree (= 8), and income is measured with 11 categories of monthly household income from less than 1,000,000 Korean Won to more than 10,000,000 Korean Won. Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of all observable variables in this study.

Findings

Instrumental Model

Figure 5 presents the results from the SEM analysis of the instrumental model. First, the multilevel analysis shows that the macro-level criminal condition, crime rate, does not retain any significant effect on individual fear of crime, perceived police effectiveness, and police confidence. To examine the random variations, we have also inspected the random intercept model for the micro-level variables and found that police confidence (σ2 = .037, p < .05) and fear of crime (σ2 = .108, p < .01) randomly varied across macro-level units, while perceived police effectiveness (σ2 = .041, p > .05) did not. These findings indicate that the levels of police confidence and fear of crime were significantly different across given boroughs; however, these variations were not associated with the macro-level status of the crime rate.

At an individual level, fear of crime (b = .068, p < .05) and perceived police effectiveness (b = − .112, p < .05) were found to be significantly driven by victimization experience. As hypothesized, individuals with more victimization experience retain a higher level of fear of crime and a lower level of perceived police effectiveness. Furthermore, the higher level of fear of crime negatively influenced perceived police effectiveness (b = − .115, p < .05). As for their influence on police confidence, however, only perceived police effectiveness had a significant direct impact on police confidence while other variables did not. We have also examined the indirect effect of victimization experience and fear of crime and found that victimization experience showed a significant negative indirect impact on police confidence (b = − .023, p < .05) while fear of crime did not (b = − .023, p < .05). Among control variables, only individuals’ income levels had presented a significant positive influence on police confidence (b = .025, p < .01).

These micro-level findings show that the core determinant of police confidence in the instrument model is individuals’ perception of police effectiveness. Contrary to findings from previous studies, this study reveals that fear of crime and victimization experience did not directly influence police confidence in South Korea. Moreover, the level of crimes at the borough level did not influence individuals’ fear of crime, perceived police effectiveness, and confidence in the police. The effects of age, sex, education, and marital status were not significantly associated with the individual level of confidence in the police, either. In sum, the analysis of the instrumental model indicates that citizens in South Korea trusted the police when they perceive that the police effectively provided their service and handle criminal incidents.

Expressive Model

To examine the argument from the neo-Durkheimian theory, we examined the expressive model and presented the result from the SEM analysis in Fig. 6. The multilevel approach shows that the macro-level status of deprivation did not significantly influence individuals’ perception of social cohesion (b = .537, p > .05) and police confidence (b = − .898, p > .05). At the micro level, individuals’ perception about general social cohesion is found to significantly influence their perceived collective efficacy (b = .551, p < .01) and formal control (b = .308, p < .01) but not their perception of informal control (b = − .076, p > .05) and confidence in the police (b = − .038, p > .05). The total indirect effect of social cohesion on police confidence was not significant, either (b = .069, p > .05).

As for effect on the police confidence, all exogenous and control variables are found not significant except perceived formal control (b = .240, p < .05) in the expressive model. Individuals with a higher level of trust in formal control (i.e., general criminal justice policies) retained greater confidence in the police. This finding indicates that individuals’ perceptions about overall formal criminal justice policies, not social cohesion, collective efficacy, or informal control, shaped their confidence in the police in South Korea.

Procedural Model

Besides the above models, we examined the procedural model that focused on the effect of perceived police fairness on confidence in the police and presented the results in Fig. 7. The results from this SEM analysis show that individuals’ victimization experience negatively influenced their perception of police fairness (b = − .0.34, p < .01), and individuals’ perceived police fairness, in turn, positively impacted their confidence in the police (b = .917, p < .01). As found in the expressive model, no control variables were significant. These results suggested that those who contacted the police due to their criminal victimization were more likely to consider the police to be unfair, and those with a lower level of perceived police fairness had a significantly lower level of confidence in the police in South Korea.

Comprehensive Model

Finally, we combined all three models to assess the relative effects of each model on confidence in the police, using a comprehensive SEM analysis and presented the results in Fig. 8. The results showed that the effect of victimization experience on fear of crime (b = .068, p < .05) and perceived police confidence (b = − .113, p < .05) and that of perceived social cohesion on collective efficacy (b = .551, p < .01) and formal control (b = .308, p < .01) were consistent with those from individual models. The non-significant effects of macro-level variables and control variables were also identical to the findings from separated analyses as given in Fig. 8.

The effects of these variables on confidence in the police, however, are distinct from previous individual models in two aspects. First, police effectiveness (b = .028, p > .05) and formal control (b = .120, p > .05) were significant in separate, individual models, but were not significant in the comprehensive model. Police fairness was the only significant variable (b = .816, p < .01) consistently across all of the models. In other words, when all models were combined, individuals’ perception of police fairness was the primary, significant determinant of confidence in the police. Secondly, victimization experience, which had a significant, indirect effect in individual models, now had a significant direct impact on confidence in the police (b = .077, p < .05). Furthermore, more victimization experience increased the level of confidence in the police, as indicated by the coefficient of victimization experience. This seemingly inconsistent finding may be interpreted as that the remaining variance of victimization experience (after controlling for fear of crime and police effectiveness) was positively associated with confidence in the police.

Model-Fit Test of SEMs

To examine each model’s capability to explain the variance in the given data, we estimated the Akaike information criterion (AIC), the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), and the sample-size adjusted BIC (ABIC) and presented the results in Table 3. The general equation of information criterion (IC) is given as:

where L indicates the maximized value of the likelihood function and θ refers to the number of parameters in a statistical model. When γ is given as 2, this function becomes the AIC statistics. If γ is equal to log(N), this function is identified as the BIC statistics, and if γ is identical to log((N + 2)/24), this function is equal to the ABIC statistics (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2017; Park & Fisher, 2017). As these model-fit statistics control for the number of parameters, they can compare both nested and non-nested models (Dayton, 2003).

As these IC statistics represent the amount of lack-of-fit, the results of the model-fit test showed that the procedural model provided the best fit to the survey data, whereas the comprehensive model provided the least model-fit. This finding suggested that perceived police fairness in the procedural model represented the most significant factor in shaping confidence in the police. This was also consistent with the findings from the comprehensive model analysis.

Discussions and Conclusion

To broaden our perspective on the intricate causal pathways leading to confidence in the police in South Korea, the current study examined three theoretical frameworks and conducted four analyses, including three separate individual analyses for each model and one comprehensive model.

Before turning to the results and their implications, we would like to caution readers with theoretical and methodological caveats of this study. First, this study was based on a one-time survey data that did not take into consideration any temporal order of variables. As Skogan (2009) pointed out, confidence in the police may play a role in the exogenous variable for explaining fear of crime or perceived police effectiveness. It is also theoretically meaningful to hypothesize that individuals with higher confidence in the police are more likely to consider police operations to be fair (Merry et al., 2012; Tyler, 1988, 2006). Future studies may enhance our study by introducing a sufficient number of second-level units and panel survey data. Second, the number of boroughs as the second-level units is 12 in our study, which may not be sufficient in fully identifying the macro-level variations. Lastly, previous studies have revealed that the public perception of distributive justice, along with procedural justice, also plays an essential role in assessing police legitimacy (Sunshine & Tyler, 2003). Future studies should extend the procedural model and include the measurement of distributive justice.

Despite these methodological caveats, the current study has generated several significant findings. First, confidence in the police is relatively low in South Korea compared with other developed countries such as Japan and the USA. While the steep decline in public’s confidence in the police during the 1980s and 1990s could be attributable to the authoritarian military rule (Boateng et al., 2016; B. Moon, 2004), the climb in public confidence in the police since the 2000s may be a sign that the public welcome the community-based policing and greater police accountability implemented by the Police Grand Reform.

Second, the instrumental and comprehensive SEM analyses show that fear of crime does not play a significant role in establishing one’s confidence in the police. This finding is somewhat inconsistent with previous studies that presented the significant negative effect of fear of crime (i.e., Jackson, 2004; Jackson & Bradford, 2009; Jang & Hwang, 2014). In their SEM analyses of the Korean National Victimization Survey, for example, Jang and Hwang (2014) found that fear of crime consistently affected confidence in the police in South Korea. We speculate that this inconsistency could be due to the operationalization of confidence in the police, as these studies included perceived police effectiveness as a core element of confidence in the police. Indeed, previous studies, which differentiated perceived police effectiveness and confidence in the police, found that police effectiveness mediated the impact of fear of crime on confidence in the police (Jackson et al., 2009).

Third, the results of the expressive model suggest that none of the key variables, such as social cohesion, informal control, and collective efficacy, was significant in predicting confidence in the police, with the exception of formal control and social cohesion. Furthermore, both significant variables became non-significant in the comprehensive model analysis. These findings suggest that Korean people were less likely to view the police as the guard of social cohesion and moral standards; instead, they regarded the police more as law enforcers and crime fighters.

Last, the SEM analyses of the procedural model and the comprehensive model revealed that police fairness and their procedural justice were the essential determinant of confidence in the police in South Korea. This finding supports the general thesis that public’s contact with the police influences their perceptions of police fairness, and in turn, affects their confidence in the police (Bradford et al., 2009; Merry et al., 2012; Tyler, 1988; Tyler & Huo, 2002). This finding is also consistent with the recent international studies, which have demonstrated the importance of procedural justice in engendering successfully policing around the world, including non-Western societies (i.e., Grant & Pryce, 2019; Pryce & Grant, 2020).

In sum, our findings in this study provided one important policy implication to Korean criminal justice policymakers. To achieve a higher level of confidence in the police, which presumably boosts the support for the police, reduces fear of crime, and prevents disorders/crimes (Bahn, 1974; Povey, 2001; Quinton & Morris, 2008; Skogan, 2009), police officers and the police institution in South Korea should place the highest priority on improving their fairness and procedural justice. Recently, the Korean police are undergoing a series of reforms, including gaining the legal status of independent investigation and establishing local self-administering agencies. For the success of these reforms, the Korean police should keep in mind the importance of procedural fairness in their operations. After all, the success of the police reforms hinges on public confidence in the police, and police fairness drives the public confidence in the police in South Korea.

Notes

It is the most recent data which is available when this manuscript is written.

Available at http://kosis.kr/eng/

References

Bahn, C. (1974). The reassurance factor in police patrol. Criminology, 12(3), 338–345.

Baker, H. M., Nienstedt, C. B., Everett, S. R., & McCleary, R. (1983). The impact of a crime wave: perceptions, fear, and confidence in the police. Law and Society Review, 17(2), 319–336.

Bartsch, R. A., & Cheurprakobkit, S. (2004). The effects of amount of contact, contact expectation, and contact experience with police on attitudes toward police. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 19(1), 58–70.

Batzeveg, E., Hwang, E., & Han, S. (2017). Confidence in the police among Mongolian immigrants in South Korea and native Mongolians in Mongolia: a comparative test of conceptual models. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 50, 61–70.

Boateng, F. D. (2016). Neighborhood-level effects on trust in the police: a multilevel analysis. International Criminal Justice Review, 26(3), 217–236.

Boateng, F. D., Lee, H. D., & Abess, G. (2016). Analyzing citizens reported levels of confidence in the police: a cross-national study of public attitudes toward the police in the United States and South Korea. Asian Journal of Criminology, 11(4), 289–308.

Bradford, B., & Myhill, A. (2015). Triggers of change to public confidence in the police and criminal justice system: findings from the Crime Survey for England and Wales panel experiment.

Bradford, B., Jackson, J., & Stanko, E. (2009). Contact and confidence: revisiting the impact of public encounters with the police. Policing and Society, 19(1), 20–46.

Bursik, R. J. (1999). The informal control of crime through neighborhood networks. Socialogical Focus, 32(1), 85–97.

Cao, L., & Dai, M. (2006). Confidence in the police: where does Taiwan rank in the world? Asian Journal of Criminology, 1(1), 71–84.

Cao, L., & Wu, Y. (2019). Confidence in the police by race: taking stock and charting new directions. Police Practice and Research, 20(1), 3–17.

Cao, L., Frank, J., & Cullen, F. T. (1996). Race, community context and confidence in the police. American Journal of Police, 15(1), 3–22.

Cao, L., Lai, Y., & Zhao, R. (2012). Shades of blue: confidence in the police in the world. Journal of Criminal Justice, 40(1), 40–49.

Dayton, C. M. (2003). Model comparison using information measures. Journal of Modern Applied Statistics Method, 2, 281–292.

Dowler, K., & Sparks, R. F. (2008). Victimization, contact with police, and neighborhood conditions: reconsidering African American and Hispanic attitudes toward the police. Police Practice and Research, 9(5), 395–415.

Fox, J. P. (2010). Bayesian item response modeling. Theory and application. New York: Springer.

Garcia, V., & Cao, L. (2005). Race and satisfaction with the police in a small city. Journal of Criminal Justice, 33(2), 191–199.

Grant, L., & Pryce, D. K. (2019). Procedural justice, obligation to obey, and cooperation with police in a sample of Jamaican citizens. Police Practice and Research: An International Journal, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2019.1644178.

Han, J., & Bu, K. (2000). A study on the improvement of police image. Police Science Collection of Treaties, 16, 1–113.

Hawdon, J., & Ryan, J. (2003). Police-resident interactions and satisfaction with police: an empirical test of community policing assertions. Crimial Justice Policy Review, 14, 55–74.

Ho, T., & McKean, J. (2004). Confidence in the police and perceptions of risk. Western Criminology Review, 5(2), 108–118.

Hoffman, V. (1982). The development of modern police agencies in the Republic of Korea and Japan: a paradox. Police Studies, 5(3), 3–16.

Holmes, M. D., Painter II, M. A., & Smilth, B. W. (2017). Citizens’ perceptions of police in rural US communities: a multilevel analysis of contextual, organisational and individual predictors. Policing and Society, 27(2), 136–156.

Hwang, E., McGarrell, E. F., & Benson, B. L. (2005). Public satisfaction with the South Korean Police: the effect of residential location in a rapidly industrializing nation. Journal of Criminal Justice, 33(6), 589–599.

Jackson, J. (2004). Experience and expression: social and cultural significance in the fear of crime. British Journal of Criminology, 44(6), 946–966.

Jackson, J., & Bradford, B. (2009). Crime, policing and social order: on the expressive nature of public confidence in policing. British Journal of Sociology, 60(3), 493–521.

Jackson, J., & Sunshine, J. (2007). Public confidence in policing: a neo-Durkheim perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jackson, J., Bradford, B., Hohl, K., & Farrall, S. (2009). Does the fear of crime erode public confidence in policing? Policing, 3(1), 100–111.

Jang, H., & Hwang, E. (2014). Confidence in the police among Korean people: an expressive model versus an instrumental model. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 42(4), 306–323.

Jang, H., Joo, H., & Zhao, J. (2010). Determinants of public confidence in police: an international perspective. Journal of Criminal Justice, 38, 57–68.

Jesilow, P., Meyer, J., & Namazzi, N. (1995). Public attitudes toward the police. American Journal of Police, 14(2), 67–88.

Joo, H. (2003). Crime and crime control. Social Indictors Research, 62(1), 239–263.

Kwak, H., & McNeeley, S. (2019). Neighbourhood characteristics and confidence in the police in the context of South Korea. Policing and Society, 29(5), 599–612. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2017.1320997.

Lee, S. (1990). Morning calm, rising sun: national character and policing in South Korea and in Japan. Police Studies, 13(3), 91–110.

Lee, H. D., Cao, L., Kim, D., & Woo, Y. (2019). Police contact and confidence in the police in a medium-sized city. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 56, 70–78.

Lind, E., & Tyler, T. R. (1988). Critical issues in social justice. The Social Psychology of Procedural Justice. New York, NY: Plenum Press.

Loader, I. (1997). Policing and the social: questions of symbolic power. British Journal of Sociology, 48(1), 1–18.

Loader, I., & Mulcahy, A. (2003). Policing and the condition of England: memory, politics and culture. Oxford; Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Merry, S., Power, N., McManus, M., & Alison, L. (2012). Drivers of public trust and confidence in police in the UK. International Journal of Police Science and Management, 14(2), 118–135.

Moon, B. (2004). The politicization of police in South Korea: a critical review. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 27(1), 128–136.

Moon, C., & Kim, Y. (1996). A circle of paradox: development, politics, and democracy in South Korea. In L. Adrian (Ed.), Democracy and development. Oxford: Polity.

Moon, B., & Maorash, M. (2008). Policing in South Korea: struggle, challenge, and reform. In M. Hinton & T. Newburn (Eds.), Policing developing democracies (pp. 101–118). New York: NY: Routledge.

Moon, B., & Zager, L. (2007). Police officers’ attitudes toward citizen support: focus on individual, organizational and neighborhood characteristic factors. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 30, 484–497.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998-2017). Mplus user’s guide (Eighth ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Nalla, M. K., & Hwang, E. (2006). Relations between police and private security officers in South Korea. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 29(3), 482–497.

Park, S., & Fisher, B. S. (2017). Understanding the effect of immunity on over-dispersed criminal victimizations: zero-inflated analysis of household victimizations in the NCVS. Crime & Delinquency, 63(9), 1116–1145.

Povey, K. (2001). Open all hours: a thematic inspection report on the role of police visibility and accessibility in public reassurance. London: Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary.

Pryce, D. K., & Grant, L. (2020). The relative impacts of normative and instrumental factors of policing on willingness to empower the police: a study from Jamaica. JOURNAL OF ETHNICITY IN CRIMINAL JUSTICE, 18(1), 19–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377938.2019.1681046.

Pyo, C. (2001). Policing: the past. Crime and Justice International, 24, 5–6.

Pyo, C. (2002). An empirical research on the public perception of the police and various police reform initiatives in Korea: 1999–2001. Asian Policing, 1(1), 127–143.

Quinton, P., & Morris, J. (2008). Neighbourhood policing: the impact of piloting and early national implementation. London: UK: Home Office.

Reisig, M. D., & Parks, R. B. (2000). Experience, quality of life, and neighborhood context. Justice Quarterly, 17, 607–629.

Ren, L., Cao, L., Lovrich, N., & Gaffney, M. (2005). Linking confidence in the police with the performance of the police: community policing can make a difference. Journal of Criminal Justice, 33(1), 55–66.

Roh, S., & Choo, T. (2007). Citizen violence against Korean police. Crime and Justice International, 23, 4–13.

Rusinko, W. T., Johnson, K. W., & Hornung, C. A. (1978). Importance of police contact in the formulation of youths’ attitudes toward police. Journal of Criminal Justice, 6(1), 53–67.

Sampson, R. J., Raudenbush, S. W., & Earls, F. (1997). Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science, 277(5328), 918–924.

Sindall, K., & Sturgis, P. (2013). Austerity policing: is visibility more important than absolute numbers in determining public confidence in the police? European Journal of Criminology, 10(2), 137–153.

Skogan, W. (2009). Concern about crime and confidence in the police. Police Quarterly, 12(3), 301–318.

Smith, P. E., & Hwawkins, R. O. (1973). Victimization, types of citizen-police contracts, and attitudes toward the police. Law and Society Review, 8, 135–152.

Stanley, D. (2003). What do we know about social cohesion: the research perspective of the federal governments’ social cohesion research network. Canadian Journal of Sociology, 28(1), 5–17.

Sunshine, J., & Tyler, T. R. (2003). The role of procedural justice and legitimacy in public support for policing. Law and Society Review, 37(3), 513–548.

Taylor, R. B., & Lawton, B. A. (2012). An integrated contextual model of confidence in local police. Police Quarterly, 15(4), 414–445.

Tyler, T. R. (1988). What is procedural justice?: criteria used by citizens to assess the fairness of legal procedures. Chicago, Ill: American Bar Foundation.

Tyler, T. R. (2003). Procedural justice, legitimacy, and the effective rule of law. Crime and Justice, 30, 283–357.

Tyler, T. R. (2006). Why people obey the law. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Tyler, T. R., & Huo, Y. J. (2002). Trust in the law: encouraging public cooperation with the police and courts.

van der Linden, W. J. (2016). Handbook of item response theory. Volume 1. Models. Boca Raton, Florida: Taylor & Francis Group.

Weitzer, R., & Tuch, S. (2002). Perceptions of racial profiling. Criminology, 40, 435–456.

Weitzer, R., & Tuch, S. (2004). Race and perceptions of police misconduct. Social Problems, 51, 305–325.

Weitzer, R., Tuch, S., & Skogan, W. (2008). Police-community relations in a majority black city. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 45, 398–428.

Xu, Y., Fiedler, M. L., & Flaming, K. H. (2005). Discovering the impact of community policing: the broken windows thesis, collective efficacy, and citizens’ judgment. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 42(2), 147–186.

Funding

This study was funded by the Korean Institute of Criminology (Grant Number: KIC 17-B-02).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

All participants provided informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Park, Sm., Lu, H., Donnelly, J.W. et al. Untangling the Complex Pathways to Confidence in the Police in South Korea: a Stepwise Multilevel Structural Equation Modeling Analysis. Asian J Criminol 16, 145–164 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-020-09321-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-020-09321-4