Abstract

Implementation and sustainment of evidence-based interventions (EBIs) is influenced by outer (e.g., broader environments in which organizations operate) and inner (e.g., organizations, their administrators, and staff) contexts. One important outer-context element that shapes the inner context is funding, which is complex and unpredictable. There is a dearth of knowledge on how funding arrangements affect sustainment of EBIs in human service systems and the organizations delivering them, including child welfare and behavioral health agencies. This study uses qualitative interview and focus group data with stakeholders at the system, organizational, and provider levels from 11 human service systems in two states to examine how stakeholders strategically negotiate diverse and shifting funding arrangements over time. Study findings indicate that, while diverse funding streams may contribute to flexibility of organizations and possible transformations in the human service delivery environment, a dedicated funding source for EBIs is crucial to their successful implementation and sustainment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

“How many millions of times do we need to say ‘the funding?’ That’s been our main challenge, our main accomplishment, our main headache. Everything has been around that.”

Government Human Services Agency Administrator

Implementing and sustaining evidence-based interventions (EBIs) in human service systems involves pairing an effective intervention with effective implementation.1 Factors associated with the outer context (e.g., systems and environments) and the inner context (e.g., organizations and their administrators and staff) affect implementation and sustainment, individually and in interaction with one another.2 A key outer-context element shaping the inner context is funding. As this study shows, the shifting and unpredictable nature of funding significantly affects the implementation and sustainment of human service EBIs.

Funding human services is complex, as the community-based organizations (CBOs) that are often contracted to deliver them have not historically operated according to the market logic governing other financial relationships, in which clients are considered “customers.” Instead, CBOs are accountable to multiple funders, subject to contractual constraints and to federal, state, and local policies and standards, and obligated to meet the needs of a growing and diverse client base, while maintaining organizational stability and staff morale.3 Increasingly, CBOs must also accommodate a shift away from relatively stable, predictable, and long-term funding arrangements and toward more competitive, short-term, and performance-based contracts.4,5,6

Funding Human Services in the United States

Funding for human services in the United States (U.S.) has evolved over time to reflect changing sociopolitical priorities. For decades, U.S. human service agencies were funded primarily by private donors and charities. However, motivated by the War on Poverty and other policy initiatives in the 1960s, the federal government expanded social services by contracting with non-government agencies. Although government contracts are still the most prevalent form of funding for human services, large-scale funding cutbacks in the 1980s have resulted in an environment in which such services, including child welfare and behavioral health, are provided largely by nonprofit CBOs financed through combinations of public and private funding.5, 7

Sociologist Kirsten Gronbjerg points out that public-sector funding sources “differ in their underlying structures, in the nature of interorganizational funding relationships they set in motion, and in the range and contingencies they impose.”3(p.8) These factors affect how CBOs operate, from the tasks and services they can bill for, to the way they track, measure, and report outcomes. Providers choose between different sources depending on these contingencies, as well as the amount of funding, and its timing, length, and prospects for renewal.3 As government contracts are affected by reduced funding and increased emphasis on competition and for-profit options, CBOs must look elsewhere for funding and embrace increased “marketization” of government contracting, including fee-for-service and performance-based contracting, the consequent shifting of risk onto providers, and increased emphasis on financial management and outcomes.5 Nonetheless, contracting for human services remains uniquely complex as human service CBOs tend to be under-capitalized, to operate in a limited field of competition, and to face difficulties delivering labor-intensive and costly services to diverse clients.5, 8

The current funding environment for human services is multifaceted. Human services increasingly rely on Medicaid to fund mental health care, substance use treatment, and social services, including child welfare.9 In addition, other government tools, such as tax credits, vouchers, waivers, and tax-exempt bonds contribute to funding CBOs.5 While private sources, such as foundations and donors, appeal to CBOs because of their independence from government mandates, they tend to be fragmented and unstable.10 Provider CBOs may also rely on earned income, such as endowments or the sale of products or services.

Several studies have examined how nonprofits evaluate funding sources11 and respond to shifts in funding.12,13,14,15 However, little research has examined the effects of funding on specific innovations, like those derived from research bases of effectiveness (i.e., EBIs), or on the service systems implementing them. Although scholarship on system-level EBI instantiation suggests that funding is an important element of the implementation environment,2, 16, 17 there is a dearth of knowledge on how diverse funding arrangements influence sustainment of EBIs delivered by CBOs. Understanding these influences specifically on sustainment of EBIs (i.e., maintenance of core elements of an intervention with fidelity over time) is a pressing need as many EBIs are not continued after preliminary implementation, wasting their often costly start-up processes.18, 19

The EPIS Framework

Scholars describe EBI implementation as a dynamic multi-stage process involving the interplay of systems, organizations, providers, and clients.2, 16, 20 To understand the effects of funding on these dimensions, this study employs the EPIS framework, which conceptualizes four phases in the implementation of EBIs: Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, and Sustainment. Each phase centers on inner- and outer-context factors that influence EBI implementation. Key inner-context factors concerning funding are CBO leadership, costs of EBIs, and organizational factors (e.g., billing procedures, administrative work to apply for and maintain funding). Outer-context factors shaping funding arrangements include the priorities of national, state, and private funders, state-level decisions about federal funds, leadership in government systems, contracts, and inter-organizational relationships.2, 3, 5, 16 For this study, the EPIS model elucidates how inner- and outer-context factors influence funding for EBIs over time.

This study features data that are longitudinal, multi-level, and multi-sited to elucidate the ways that funding arrangements influenced the implementation of a child welfare EBI: (1) at every stage, from the decision to implement the intervention to its sustainment over several years; (2) in inner and outer contexts from the perspectives of system and CBO stakeholders; and (3) in a variety of settings, including established and publicly funded CBOs as well as smaller agencies, some of which had limited access to, or flexibility in, public funding. The depth and breadth of this research into a specific EBI thus represents an important contribution to understanding the central influence of funding priorities, processes, and decision making on the provision of EBIs more generally, especially in the current environment of emphasizing market-based competition and both public and private financial uncertainty.5

Methods

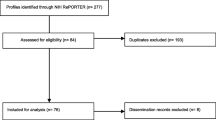

This study draws on interviews and focus groups with system, organizational, and frontline stakeholders from one statewide and 10 countywide child welfare systems in two states. Each service system delineated a government human service agency and the CBOs tasked with delivering child welfare services under its purview. This substantial and descriptive dataset documents how these actors strategically arranged funding to implement and sustain SafeCare®, an evidence-based in-home parenting intervention for families reported or deemed at-risk for child maltreatment.21,22,23 The dataset was compiled over more than 10 years from three iterative studies of implementation24,25,26 and follow-up research on sustainment.27 With the exception of one county, SafeCare was delivered by CBOs contracted by state or county government agencies (many of which also delivered behavioral health services and worked with clients receiving such services), and was funded by a variety of public and private sources. Initial training was supported by federal grant funding; the responsibility for funding service provision and subsequent training and coaching then fell upon the state or county.

Data Collection and Analysis

This study utilizes secondary analysis of preexisting data collected during a series of mixed-method studies of SafeCare implementation readiness, actual implementation, and sustainment in multiple service systems.2, 25, 28 Individual semi-structured interviews (n = 175), small group interviews with an average of three participants (n = 13), and focus groups with an average of six participants (n = 80) were conducted with a wide range of stakeholders involved in SafeCare in each system. System-level stakeholders were government administrators (e.g., directors of state- or county-run child welfare agencies), CBO administrators (e.g., executive directors and program managers), academic collaborators, and funders (e.g., administrators of public and private funding agencies). Frontline stakeholders were home visitors tasked with delivering SafeCare and their supervisors and coaches.

Systems were classified according to their EBI sustainment status: “fully-” (n = 7), “partial-” (n = 1), and “non-” (n = 3).29 Fully-sustaining systems maintained core elements of SafeCare at a sufficient level of fidelity after initial implementation support had ended, and adequate capacity existed (e.g., training for new staff; ongoing fidelity monitoring and coaching) to maintain these elements. Partial-sustaining systems met only some of the core elements (e.g., did not conduct model-required fidelity monitoring and coaching) after withdrawal of initial support. In non-sustaining systems, SafeCare was no longer being implemented by any home visitors.

Data were collected at three time points that varied according to when SafeCare began in each system: Time 1 (T1; initial Implementation phase for two sites; 2006–2008), Time 2 (T2; initial Implementation phase for nine sites, later Implementation/Sustainment phase for first two sites; 2009–2011), and Time 3 (T3; Sustainment phase for all sites; 2012–2014). Data were collected in at least one system each year across all time periods. The majority of data collection for this analysis occurred in T3 when systems had all been implementing SafeCare for a minimum of 2 years and were in the Sustainment phase. Several stakeholders with long tenures in their positions were interviewed multiple times during the study.

Interview and focus group guides examined factors pertinent to the EPIS phases of SafeCare in each service system. Interviews in T1 asked about the Exploration, Preparation, and early Implementation phases (i.e., perceptions of SafeCare; development of implementation procedures; prospective inner- and outer-context factors affecting implementation, including system leadership, contracting processes, and funding). Interviews in T2 further investigated the Implementation phase (i.e., successes and challenges of implementation; how SafeCare was working within each service system). Interviews in T3 focused on the later Implementation and Sustainment phases (i.e., inner- and outer-context factors influencing implementation success and sustainment of SafeCare). Separate guides were developed for system-level, CBO, and frontline stakeholders. Table 1 details questions pertaining specifically to the financing of SafeCare. Notably, however, funding and billing issues arose as topics of particular concern in participant responses throughout the interviews (e.g., in response to general questions about challenges of SafeCare implementation or factors that may affect SafeCare sustainment). An iterative process was used to develop guides to ensure consistency of topic areas and questions.

Interviews and focus groups were digitally recorded, professionally transcribed, and checked for accuracy. The authors utilized NVivo 10 qualitative data analysis software30 in a process of repeated review and analysis. In the primary analysis of these studies, the data were coded by research assistants and condensed into analyzable units. Codes were assigned to segments of text based a priori on topic areas and interview questions.31 For the secondary analysis in this study, the first author created additional codes based on key sensitizing concepts from the implementation literature, including funding, budget, contract, and billing. These concepts provided “a general sense of reference”31(p.545) and supplied descriptive data based in the words of participants, enabling the research team to examine their salience and meaning for different stakeholders over time. Open and focused coding were then used to locate new themes and issues related to funding (e.g., “creative financing,” “billing problems,” “funding insecurity”), and to determine which themes emerged frequently or represented particular concerns.32 The first author independently coded the transcripts, created detailed memos that described and linked codes to each theme, and shared this work with the larger team to be reviewed and checked for accuracy. Discrepancies in analysis were discussed and resolved by the entire research team. Through comparing and contrasting codes generated by multiple coders in the primary and secondary analysis of the data, codes with similar content were grouped into broad themes linked to segments of text.32, 33 Final themes illuminate the role funding played in implementing and sustaining SafeCare.

Results

Themes are divided into outer-context (i.e., system-level) and inner-context (i.e., CBO-level) perspectives. Table 2 organizes results by EPIS phase and sustainment status.

Funding a Home Visitation EBI

Fully-sustaining Systems

In the majority of fully-sustaining systems, SafeCare was funded by blended streams of federal, state, and county money. These included state discretionary funds for child welfare, state funds for mental health services, and county general funds. In most cases, systems contracted with CBOs or other existing home visitation programs to implement SafeCare. For example, in one system, CBOs were contracted to deliver SafeCare using special funding for prevention and early intervention via a state ballot proposition for mental health services. In another, public health nurses were trained to deliver SafeCare using county general funds for child welfare and social services with the help of federal matching funds. In a third system, a private charitable organization funded initial implementation, after which SafeCare was supported by federal, state, and county money. Several fully-sustaining systems received support from a statewide initiative to use tobacco taxes to fund early childhood programs.

Partial-sustaining Systems

In the partial-sustaining system, the local child welfare agency contracted with CBOs using state funding dedicated to home visitation services and a federal child welfare block grant. Funding from these sources decreased over time.

Non-sustaining Systems

In the non-sustaining systems, SafeCare was added to the existing caseloads of government social workers or CBO staff. No new funding streams were found to support SafeCare. In one case, government administrators hoped to fund SafeCare as part of the “select” child welfare services eligible for Medicaid dollars; however, they were unable to get all of the SafeCare modules to fit reimbursement rules. Although they tried to leverage other funding streams to make up the difference, the CBO reverted to services as usual.

Outer-Context Perspectives

Securing and Maintaining Funding

For administrators of government agencies and CBOs, efforts to find, secure, and maintain adequate funding were a nearly constant activity. Across all service systems, these administrators characterized their efforts to leverage various funding streams to cover the costs of service provision as a necessary but challenging aspect of human services. One CBO administrator commented, “If it was just me as a social worker, I love [SafeCare]. We love the results it gets, but . . . I feel the pressure to maintain peoples’ jobs and quality of services, so money always comes up, unfortunately.” Other CBO administrators agreed that the need to prioritize funding was regrettable, yet inseparable from service provision.

While funding concerns were commonplace, government and CBO administrators in fully-sustaining systems were proactive, strategic, and creative in pursuing funding. When asked about their roles in planning and contracting for SafeCare, several government administrators used the term “creative financing” to characterize their efforts in prioritizing programs, exploring financing streams, and strategically applying often fluctuating funds to serve clients and meet outcomes. This also involved recognizing the often disparate goals of funders and determining how best to demonstrate to them that their goals were indeed aligned.

Government administrators in fully-sustaining systems managed an added layer of complexity by foreseeing future program and funding changes. For example, early in the Implementation phase in a system where SafeCare was delivered partly by federal civil service program volunteers, government administrators were already planning how to sustain the EBI when the volunteers ended their tenures a year or two in the future. In another system, administrators limited home visitor caseloads, despite a substantial in-flow of implementation funding, to prevent future cuts when funding returned to normal. In these cases, administrators planned for changes months or years ahead. In contrast, sustainment was compromised in partial- and non-sustaining systems by unanticipated issues. For example, in one system, unforeseen difficulties in billing Medicaid for SafeCare resulted in home visitors not getting paid.

For their part, CBO administrators engaged in similar types of negotiations around funding at the organizational level. For several CBOs with broad service portfolios not limited to SafeCare, this took the form of juggling funding among different programs. For example, one program manager in the partial-sustaining system recounted the “creative financing” involved:

There’s about four different contracts that we’re working under to support [a program]. . . . One contract was taken away, but then we got some other funding, a small $10,000 one, where we were able to put that in. . . . With [another program], we found some money [but] we went from six to three caseworkers. . . . It was on the verge of being taken away.

In some fully-sustaining systems, CBO administrators’ “creative financing” involved collaborating with other CBOs. In response to a question about interorganizational partnerships, one CBO director described her/his organization’s relationship with another CBO, “We work together to look for additional funding sources to expand upon what we’re doing, or emphasize a mutual need.” Others shared contracts with CBOs that were having trouble or just starting SafeCare, allowing for coverage and continuity of care. In one system, organizations arranged subcontracts to maintain the program despite the financial difficulties of one CBO. One of the CBO directors involved recalled, “I said, I know [smaller CBO]’s having some troubles, is there a way that we can bring your [larger CBO] network of contractors together . . . so we can sustain the services?” Strategic planning, creative problem solving, and foresight on the parts of both government agencies and CBOs were thus crucial characteristics of successful implementation and sustainment of SafeCare. However, one CBO administrator underlined the burden that these tasks put on CBOs, “Everybody’s grant or contract might look a little bit different . . . and who do we turn things into and who are we getting information back from and how do we incorporate that into what we do here, along with all the other stuff that we already have to begin with?”

Challenges and Opportunities of Funding EBIs

Stakeholders across the systems reported opportunities and challenges associated with funding an EBI. There was a widespread perception that EBIs attracted more funding than programs lacking an evidence base. While discussing policies affecting SafeCare, a CBO director observed, “I believe that there’s a paradigm shift happening . . . [with] funders in general. Our RFPs [Requests for Proposals] now are specifically requesting those evidence-based programs.” This was confirmed by an individual from a funding agency: “The more attractive it is to donors, the more money we’re gonna raise, the more money we can invest in the community. And so we did feel that SafeCare would really offer that.” Accordingly, in the Exploration and Preparation phases, the perception that EBIs were attractive to funders played a significant role in the decision to implement SafeCare in multiple systems.

However, stakeholders also reported challenges in funding the EBI. One barrier was that SafeCare was initially omitted as an approved evidence-based model on a list of federal grant opportunities. Government and CBO administrators reported trouble paying for coaching, outreach to referral agents, training, and materials. After a competitive contract bidding process, a CBO director recalled worrying that commitment to SafeCare might result in the CBO “pricing themselves out” of consideration. In the Exploration and Preparation phases, administrators confirmed that the cost and reduced caseload of SafeCare were reflective of the program’s quality; yet, they worried that securing adequate funding posed a challenge to sustainment.

Contracting for SafeCare

System-level stakeholders reported that SafeCare integration in contracts played a significant role in sustainment. In fully-sustaining systems, SafeCare contracts were clear and detailed, setting out funding levels for the aspects and stages of service delivery, including training, coaching, reimbursement rates, and referral sources. Stakeholders cited the inclusion of such details as important for success. In the Preparation phase, the development of detailed contracts involved extensive negotiation by funders, government agencies, and CBOs.

In contrast, contracts in non-sustaining systems tended to be minimal and non-specific. In two non-sustaining systems, government agencies attempted to incorporate SafeCare into existing structures for service delivery and billing, without additional contract specifications. In a third non-sustaining system, a government administrator pointed to lack of detail in the SafeCare contract as a reason implementation failed, “I think the contract . . . really didn’t encapsulate implementation of an evidence-based practice. What we know now, we would have put explicit language in there in terms of expectations around implementation, [and] different components of the SafeCare project.” In these systems, the contract’s lack of detail concerning funding and staffing, chains of authority, goals, and outcomes, prevented administrators from dealing with contingencies, including changes in referral sources and obstacles with billing.

Funding Insecurity

The most consistent theme underlying interviews was funding insecurity. When asked about factors affecting sustainment of SafeCare, one CBO director echoed others, explaining, “Every traditional pot of funding has a little bit of a question mark by it.” Public funding was perceived as frequently changing. A second CBO director worried that SafeCare’s status as a social program made it a target of funding cuts in a conservative political climate. Private funding was also perceived as subject to economic downturn or changing priorities.

System-level stakeholders nearly universally agreed throughout all EPIS phases that funding ultimately determined the future of the intervention, and most were resigned to the possibility that it could change at any moment. A government administrator from a fully-sustaining system stated, “If you don’t have money, you don’t have SafeCare, honestly. It’s fiscal year to fiscal year.” Another expanded, “Any government contract is contingent upon funding. So if funding gets pulled at any level, those contracts are gone.” Funding fluctuations that might endanger sustainment were accepted as a possibility even in systems that had made substantial financial and organizational commitments to SafeCare.

For at least one non-sustaining system, lack of funding represented an insuperable barrier. A government administrator explained, “This is going on in the middle of the worst economic downturn we’ve faced in my career. Sometimes as important as initiatives [like SafeCare] are, the bottom line is we have to get our mandates done.” While stakeholders in this system believed in the benefits of SafeCare, this belief was not enough to protect it from funding insecurity.

Inner-Context Perspectives

Billing, Caseloads, and Fidelity

In discussing SafeCare, frontline staff reported that billing for services was a frequent concern. In one system, CBOs had transitioned from cost reimbursement to a fee-for-service contract delineating billable activities, which home visitors worried precluded them from being paid for necessary work, like making calls, preparing for home visits, and doing paperwork. While these concerns pre-dated SafeCare, early implementation of the EBI reinforced home visitors’ apprehensions. One group discussed drop-by visits to check on a family, “At this point, if you’re doing a SafeCare module, it’s like I have to sneak in a drop-by . . . [but] it’s not billable. So the billing is kind of . . . conflicting with [fidelity].”

Home visitors also reported feeling pressure to serve as many clients as possible, while still maintaining fidelity to SafeCare. A CBO director commented, “I think there’s a little tension between taking the time you need . . . and the drive for billable hours.” Fully-sustaining systems relied on CBO administrators and mid-level staff, such as coaches and supervisors, to buffer frontline staff from the demand to serve more clients and make more billable hours. For example, a second CBO director described the need to “[start] a dialogue” with the government agency about, “If this is how much money you give us, then this is the maximum number of cases we can carry with that amount of staff and still do the coaching and still do the training.” In another fully-sustaining system, supervisors of nursing staff who delivered SafeCare intervened with the government agency, which was continually pushing for more clients to be seen. The effectiveness of government and CBO administrators to establish billing procedures and caseload limits was key to home visitors’ success and job satisfaction. Where such procedures were less clearly delineated, home visitors were not able to continue delivering SafeCare.

CBO Size and Stability

While child welfare services were ostensibly paid for through contracts, organizational-level stakeholders emphasized that CBOs take on a financial burden when they contract to deliver services. Several CBO administrators mentioned that their organizations had to subsidize aspects of SafeCare, such as supplies like first aid and safety kits, as well as other elements common to in-home services, including home visitation travel costs, and time for outreach to referral agents. Administrators indicated that their ability to subsidize these costs was due to the size and stability of their organizations. One director commented, “The reason we’re lucky . . . is because we have a Development Department, and they’re out there fundraising.” Another stated, “Luckily we have a bit of a nest egg that was invested. . . . That’s how we can subsidize programs that we think are valuable.” In one fully-sustaining system, a CBO director reflected on the financial burden of a new contract bidding process, “We’ve got enough meat on our bones to figure out how to [bid for a new contract], but if you were small and you were mostly a provider organization, I don’t know how they would know how to complete this thing.” In this case, CBOs that came through the bidding process successfully did so in part because of their existing resources. In contrast, CBOs in non-sustaining systems lacked the “nest egg” to continue SafeCare without supplemental funding. In these systems, CBO administrators and home visitors struggled when caseloads increased, while funding stayed static or decreased.

Funding Insecurity

Like system- and CBO-level administrators, home visitation staff and their coaches and supervisors consistently described funding as unstable, insecure, and insufficient. One group of home visitors summed up, “We’re just always stretched.” When asked if SafeCare would be sustained over the long term, they commented, “It depends on the [child welfare] budget.” A CBO director recalled a cut in the contract, “I tried to explain it’s not that you’re not doing good work [or] we don’t value the program. But every year, you never know what’s going to be funded, what’s going to decrease, what’s going to increase.” This lack of control filtered down to home visitors, coaches, and supervisors, who voiced frustrations about their inability to anticipate available funding to spend on service provision for families or trainings.

Discussion

For administrators and staff of nonprofit and public-sector service organizations, funding is an omnipresent consideration. Despite their historic reliance on government contracts, they increasingly contend with a pervasive insecurity of government funding, coupled with a growing emphasis on market competition and for-profit models of financial management.8 Consequently, human service providers, including child welfare and behavioral health providers, largely work in environments of financial diversification and uncertainty, in which they “have access to a greater variety of revenue sources than other organizations, but are less able to control them.”3(p.22) These dynamics are increased in contexts of economic uncertainty, like the aftermath of the 2007–2008 U.S. financial crisis, which led to declines in contributions and other funding for nonprofit organizations like those in this study.34 For study participants across the outer and inner contexts of service systems, the source, amount, and stability of funding was a preoccupation and blended streams of public and private money were the norm, often involving “creative financing” through multifaceted arrangements of funding, program outcomes, and staff.

Consistent with models of implementation leadership, both CBO and government administrators in this study exhibited creativity, discernment, and proactive planning throughout the EPIS phases.35, 36 These findings resonate with Gronbjerg’s2 suggestion that instability of funding may increase innovation among nonprofit providers of human services. Both system and organizational leadership were important in SafeCare sustainment by virtue of proactive planning by government administrators and funders, and engaged leadership from CBO administrators.28 Having multiple organizational budgets and the ability to collaborate with other CBOs were two commonly cited reasons that systems could sustain SafeCare amidst funding shifts. These findings suggest that organizations balance autonomy from, and dependence on, institutions (e.g., funders, government agencies) and other organizations.37 Creative financing allowed many CBO administrators to secure resources while not becoming dependent on any one funding source. However, these arrangements favored CBOs with the size and stability to control collaborations and accommodate the burdens of finding and securing funding, while smaller CBOs were more vulnerable to the vicissitudes of both funders and CBO collaborators.38 Here, leaders of larger CBOs were able to access financial resources while maintaining power and decision-making capacity, while those of smaller CBOs were only able to obtain needed resources by becoming dependent on other organizations.

SafeCare’s status as an EBI intensified these dynamics. Implementation and sustained use of SafeCare incurred more costs than usual services, both at start-up (e.g., training) and over time (e.g., coaching and additional training to address staff turnover). However, government and CBO administrators in fully-sustaining systems were able to dedicate funding to these components, often tapping into special funding for EBIs. In contrast, these requirements were an obstacle for systems where SafeCare was incorporated into existing funding. In fully-sustaining systems, dedicated funding was largely due to contracts that specified SafeCare and its components. In these systems, SafeCare aligned with the expectations of funders and leaders of government agencies, who valued EBIs specifically. Institutional pressure to adopt SafeCare via encouragement from leadership to pursue child welfare EBIs, as well as contract and funding structures that designated SafeCare, both provided the impetus for, and helped to ensure the success of, SafeCare implementation.39,40,41,42 In contrast, government administrators in non-sustaining systems pointed to the lack of institutional structures (e.g., a contract to secure funding and provide guidance in addressing unexpected problems/costs) as a reason SafeCare was not maintained.

In addition, fully-sustaining systems in this study featured significant collaboration and communication between system, organizational, and frontline leadership. Funders, government administrators, and CBO leaders actively engaged with one another in planning for future funding changes, while frontline supervisors communicated with CBO and government stakeholders about the challenges facing their staff. These relationships exhibited the type of ongoing trust and communication that researchers of public administration suggest are key to successful human service contracts43, 44 and implementation and sustainment of EBIs.26, 45

Scholars46, 47 have applied the anthropological concept of “bricolage” to describe the flexible mobilization of diverse resources. The concept of bricolage implies the possibility of transformation in the way human services are supported and delivered as “creative financing” may challenge existing funding structures and legitimize alternative arrangements of resources. For example, funding arrangements in this study sometimes de-emphasized the traditional role of government in contracting for human services as government and CBO administrators utilized a collaborative and interactive process that relied on alternative funding sources, such as private foundations to support scale-up, then transitioning to system-supported funding and contracting. Another possible transformation may be evidenced by the creativity of CBO administrators in this study in sharing risk and responsibility by working together to bid for and undertake contracts and search for funding.48 These efforts may counteract trends in contracting that emphasize the creation of “markets” for human services through competition among providers.5

The consequences of such transformations must be examined, especially as they impact CBOs. Further research is needed to investigate whether a diversified funding base and less reliance on government financing ultimately increases the precariousness of providers or, alternatively, encourages them to grow and achieve financial stability.49 While financial independence and flexibility may be attractive, they also represent a shifting of risk and responsibility from federal, state, and county agencies onto local government agencies and nonprofit organizations. Comments by CBO administrators in the study point to the major financial, time, and staff commitments made by CBOs in their efforts to implement and sustain SafeCare. These commitments are especially burdensome on the staff of smaller CBOs with limited portfolios of services and lessened abilities to search out new programs and funding streams. Additionally, study findings suggest that funding policies may exert an unrecognized toll on CBOs, as funding decisions made at the system level may filter down in the form of pressure on CBO staff to increase hours and numbers of clients, even as funding levels decrease. The need to search out additional funding sources with sundry bidding requirements also places a burden on administrative staff. The significance of this burden is underscored by theory in public administration positing a “deficit model of collaborative governance,”50 in which governments delegate the delivery of mandated public benefits (like child welfare) to private organizations without fully-covering the costs of those services, which may jeopardize the quality and sustainment of services by weakening the fiscal health of service providers.

Implications for Behavioral Health

This study reveals the various impacts of a changing funding environment on the provision of human services. Study findings indicate several strategies that government and CBO administrators, as well as policy makers at the national level, can undertake to ensure the sustainment of behavioral health EBIs over time. First, while many government agencies and CBOs successfully leverage diverse funding streams to implement and sustain EBIs, study findings show that their ability to accurately estimate the expense of implementation and intervention delivery51 and to carve out a dedicated funding stream to support the specific costs of EBIs throughout the Implementation and Sustainment phases is paramount to sustainment.

To do this, government and CBO administrators must establish detailed contracts outlining EBI components and outcomes. Consistent with the EPIS framework, government administrators must work to unify the requirements of funders, clients, and the EBI into a clear service contract detailing the funding particular to each EBI component, a schedule for funding levels over time, and roles and responsibilities related to decision making.1 This type of specificity can also protect smaller CBOs with fewer existing assets from incurring unforeseen expenses during implementation. Nonetheless, study findings suggest that while smaller CBOs can draw on collaborations with larger organizations for resources to implement and sustain EBIs, they will require additional financial capacity building to avoid operating at a disadvantage in accommodating the administrative costs of competitive bidding processes and complex reporting requirements. The deficit model of collaborative governance predicts that CBO administrators may be tempted to under-invest in their own organization to meet these costs, ultimately jeopardizing the quality of services provided.50 In fact, CBO administrators must strongly advocate for the full cost of service provision, including administrative expenses and cost of living increases, to be included in contracts with government agencies. They may also consider investing in resources, such as grant writers, to seek and secure multiple sources of funding.

Second, system-level stakeholders (i.e., administrators of government agencies) can take the opportunity of negotiating contracts to influence the funding environment itself.45 For example, they can emphasize relational or collaborative contracting approaches, which emphasize familiarity between partners, goal agreement, communication quality, and cooperation.52 They can also establish contracts that emphasize outcomes (i.e., quality) over CBO productivity (i.e., quantity), thereby placing increased value on EBIs and improving impact compared to services as usual.53 Government administrators can balance the specificity of contract requirements with policies that increase the flexibility of resources for CBOs such as “pooled funding” agreements, which reinvest savings of reduced recidivism in prevention EBIs.54 Contracts can include targeted variability with regard to referrals, so that more funding is available when referral numbers are high, and less when they decrease. Administrators and mid-level staff of CBOs, such as coaches and supervisors, should be included in these decisions to ensure that the experiences and knowledge of frontline staff are considered. Such built-in flexibilities may allow for government and CBO administrators to potentially transform the conventional way in which funding levels dictate policies and procedures of organizations. Additionally, multi-level contract negotiations must re-occur regularly, as financing levels change over time. These opportunities for inner- and outer-context stakeholders to build trust, communicate respective needs, and devise creative arrangements of resources and responsibilities contribute to long-term sustainment, collaborative inter-organizational relationships, and increased flexibility of resources that facilitate long-term planning, thus challenging the dominance of funding in determining the success of beneficial EBIs.

Third, policy makers at the national level must attend to the specific challenges of local government agencies and CBOs and take steps to increase availability of funding for innovative and effective programs. The Medicaid expansion under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act provided an opportunity for CBOs to increase their client base and capacity,55 though Medicaid does not currently cover non-medical expenses, such as child maltreatment prevention. The unevenness of Medicaid expansion across states, the fact that many decisions about eligibility requirements occur at the state level, and the uncertainty of Medicaid’s future leave human service providers vulnerable to political will. Moreover, policy makers must draw from the experiences of stakeholders implementing EBIs, like those in this study, to improve the availability and types of support to sustain child welfare EBIs in contexts of financial insecurity.

Finally, government administrators interested in implementing EBIs must be mindful of the dangers of the deficit model of collaborative governance and consider ways to limit the pressure on CBOs to subsidize services. Although inner-context expenses and concerns may not be effectively communicated to child welfare decision makers, government administrators and funders must understand the downstream effects and unintended consequences of funding on CBO staff. Procedures for information-sharing between the inner and outer contexts of child welfare provision would help increase understanding about what is feasible while recognizing the ethical commitment that many CBO administrators and staff make to implement innovative and effective services, rather than treating them simply as contractors. By thus recognizing and cultivating the inner-/outer-context partnership involved in implementing and sustaining EBIs such as SafeCare, child welfare stakeholders can strengthen the ability of government agencies and service providers to meet the needs of child welfare clients despite the pressures of economic uncertainty and market-based competition in human service provision.

References

Chamberlain P, Roberts R, Jones H, et al. Three collaborative models for scaling up evidence-based practices. Administration and Policy in Mental Health & Mental Health Services Research. 2012;39(4):278–290.

Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, Horwitz SM. Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health & Mental Health Services Research. 2011;38(1):4–23.

Gronbjerg KA. Understanding nonprofit funding: managing revenues in social services and community development organizations. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1993.

Collins-Camargo C, McBeath B, Ensign K. Privatization and performance-based contracting in child welfare: recent trends and implications for social service administrators. Administration in Social Work. 2011;35(5):494–516.

Smith SR. The political economy of contracting and competition. In: Hasenfeld Y (Ed). Human services as complex organizations, second edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2010, pp. 139–160.

Willging CE, Aarons GA, Trott EM, et al. Contracting and procurement for evidence-based interventions in public-sector human services: a case study. Administration and Policy in Mental Health & Mental Health Services Research. 2016;43(5):675–692.

Smith JR, Lipsky M. Non-profits for hire: the welfare state in the age of contracting. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993.

Bunger AC, Collins-Camargo C, McBeath B, et al. Collaboration, competition, and co-opetition: interorganizational dynamics between private child welfare agencies and child serving sectors. Children and Youth Services Review. 2014;38:113–122.

Stroul BA, Manteuffel BA. The sustainability of systems of care for children’s mental health: lessons learned. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2007;34(3):237–259.

Gronbjerg KA, Martell L, Paarlberg L. Philanthropic funding of human services: solving ambiguity through the two-stage competitive process. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. 2000;29(suppl 1):9–40.

Kearns KP, Bell D, Deem B, et al. How nonprofit leaders evaluate funding sources: an exploratory study of nonprofit leaders. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. 2014;43(1):121–143.

AbouAssi K. Hands in the pockets of mercurial donors: NGO response to shifting funding priorities. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. 2013;42(3):584–602.

Kaynama SA, Keesling G. An empirical investigation of the nonprofit organization responses to anticipated changes in government support for HIV/AIDS services: a cross-regional analysis. Journal of Business Research. 2000;47(1):19–26.

McMurtry SL, Netting FE, Kettner PM. How nonprofits adapt to a stringent environment. Nonprofit Management and Leadership. 1991;1(3):235–252.

Thompson JD. Organizations in action. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 1967.

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, et al. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science. 2009;4:50.

Jones AM, Bond GR, Peterson AE, et al. Role of state mental health leaders in supporting evidence-based practices over time. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2014;41(3):347–355.

Massatti RR, Sweeney HA, Panzano PC, et al. The de-adoption of innovative mental health practices (IMHP): why organizations choose not to sustain an IMHP. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2008;35(1–2):50–65.

Romance NR, Vitale MR, Dolan M, et al. An empirical investigation of leadership and organizational issues associated with sustaining a successful school renewal initiative. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association. New Orleans, Louisiana, 2002.

Meyers DC, Durlak JA, Wandersman A. The quality implementation framework: a synthesis of critical steps in the implementation process. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2012;50(3–4):462–480.

Gershater-Molko RM, Lutzker JR, Wesch D. Project SafeCare: improving health, safety, and parenting skills in families reported for, and at-risk for child maltreatment. Journal of Family Violence. 2003;18(6):377–386.

Chaffin M, Hecht D, Bard D, et al. A statewide trial of the SafeCare home-based services model with parents in child protective services. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):509–515.

Whitaker DJ, Ryan KA, Wild RC, et al. Initial implementation indicators from a statewide rollout of SafeCare within a child welfare system. Child Maltreatment. 2012;17(1):96–101.

Aarons GA, Sommerfeld DH, Hecht DB, et al. The impact of evidence-based practice implementation and fidelity monitoring on staff turnover: evidence for a protective effect. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(2):270–280.

Aarons GA, Green AE, Palinkas LA, et al. Dynamic adaptation process to implement an evidence-based child maltreatment intervention. Implementation Science. 2012;7:32.

Hurlburt M, Aarons GA, Fettes DL, et al. Interagency collaborative team model for capacity building to scale-up evidence-based practice. Children and Youth Services Review. 2014;39:160–168.

Aarons GA, Green AE, Willging CE, et al. Mixed-method study of a conceptual model of evidence-based intervention sustainment across multiple public-sector service settings. Implementation Science. 2014;9:183.

Aarons GA, Fettes DL, Hurlburt MS, et al. Collaboration, negotiation, and coalescence for interagency-collaborative teams to scale-up evidence-based practice. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2014;43(6):915–928.

Stirman SW, Kimberly J, Cook N, et al. The sustainability of new programs and innovations: a review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future research. Implementation Science. 2012;7:17.

QSR International. NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software, Version 10 [computer program]. 2012.

Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods: integrating theory and methods, fourth edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2015.

Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory, third edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2008.

Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. New York, NY: Aldine de Gruyter, 1967.

Morreale JC. The impact of the “Great Recession” on the financial resources of nonprofit organizations. Wilson Center for Social Entrepreneurship. 2011: Paper 5. http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/wilson/5

Aarons GA, Ehrhart MG, Farahnak LR. The Implementation Leadership Scale (ILS): development of a brief measure of unit level implementation leadership. Implementation Science. 2014;9:45.

Aarons GA, Green AE, Trott EM, et al. The roles of system and organizational leadership in system-wide evidence-based intervention sustainment: a mixed-method study. Administration and Policy in Mental Health & Mental Health Services Research. 2016;43(6):991–1008.

Aldrich HE. Organizations and environments. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1979.

Pfeffer J. New directions for organization theory: problems and prospects. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Aldrich HE, Ruef M. Organizations evolving, second edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2006.

Meyer JW, Scott WR. Organizational environments, ritual and rationality. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, 1992.

DiMaggio PJ, Powell WW. The Iron Cage revisited: institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review. 1983;48(2):147–160.

DiMaggio PJ, Powell, WW (Eds). The new institutionalism in organizational analysis. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2012.

Romzek BS, Johnston JM. Effective contract implementation and management: a preliminary model. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 2002:12(3):423–453.

Flaherty C, Collins-Camargo C, Lee E. Privatization of child welfare services: lessons learned from experienced states regarding site readiness assessment and planning. Children and Youth Services Review. 2008;30(7):809–820

Aarons GA, Ehrhart MG, Farahnak LR, et al. Aligning leadership across systems and organizations to develop a strategic climate for evidence-based practice implementation. Annual Review of Public Health. 2014;35:255–274.

Baker T, Nelson RE. Creating Something from Nothing: Resource Construction through Entrepreneurial Bricolage. Administrative Science Quarterly. 2005;50(3):329–366.

Desa G. Resource Mobilization in International Social Entrepreneurship: Bricolage as a Mechanism of Institutional Transformation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. 2012;36(4):727–751.

Bunger AC. Administrative coordination in non-profit human service delivery networks: the role of competition and trust. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. 2013;42(6):1155–1175.

Crittenden WF. Spinning straw into gold: the tenuous strategy, funding, and financial performance linkage. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. 2000;29(suppl 1):164–182.

Marwell NP, Calabrese T. A deficit model of collaborative governance: government-nonprofit fiscal relations in the provision of child welfare services. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 2014;25:1031–1058.

Saldana L, Chamberlain P, Bradford WD, et al. The Cost of Implementing New Strategies (COINS): a method for mapping implementation resources using the stages of implementation completion. Children and Youth Services Review. 2014;39:177–182.

Amirkhanyan AA, Kim HJ, Lambright KT. Closer than “arms length”: understanding the factors associated with collaborative contracting. The American Review of Public Administration. 2012;42(3):341–366.

White H. Current challenges in impact evaluation. European Journal of Development Research. 2014;26(1):18–30.

McCarthy P, Kerman B. Inside the belly of the beast: how bad systems trump good programs. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2010;37(1–2):167–172.

Allard SW, Smith SR. Unforeseen consequences: Medicaid and the funding of nonprofit service organizations. Journal of Health Politics, Policy, & Law. 2014;39(6):1135–1172.

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by U.S. National Institute of Mental Health grants R01MH072961 and R01MH092950, National Institute on Drug Abuse grant R01DA038466, and U.S. Centers for Disease Control grant R01CE001556 (Principal Investigator—Gregory A. Aarons). We thank participants from the service systems, organizations, and the participating providers and coaches for their collaboration and involvement in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors certify that they have no financial or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials of this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jaramillo, E.T., Willging, C.E., Green, A.E. et al. “Creative Financing”: Funding Evidence-Based Interventions in Human Service Systems. J Behav Health Serv Res 46, 366–383 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-018-9644-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-018-9644-5