Abstract

Recent evidence attests to the shortcomings of typical services for improving outcomes among emerging adults with serious mental health conditions (SMHCs). Researchers and providers have responded by developing new programs and interventions for meeting the unique needs of these young people. A significant number of these programs and interventions can be described as taking a positive developmental approach, which is informed by a combination of theoretical sources, including theories of positive development, self-determination, ecological systems, and social capital. To date, however, there has been no comprehensive theoretical statement describing how or why positive change should occur as a result of using a positive developmental approach when intervening with this population. The goal of this article is to propose a general model that “backfills” a theory behind what appears to be an effective and increasingly popular approach to improving outcomes among emerging adults with SMHCs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In the USA and other Western countries, the length of time between the end of adolescence and the attainment of various markers of adulthood has been increasing over the past few decades. Compared to earlier cohorts, young people now are taking longer to complete their education, establish a career, and achieve financial independence, and they marry and establish families later.1 This extended period of being “in between” adolescence and adulthood is now increasingly recognized as a discrete stage of life, and referred to as “emerging adulthood.” According to Arnett,1 who coined the term, this period of life extends between the years of about 18 and 25, and it is typical for young people in this stage of life to be focused on identity exploration and to experience a great degree of instability, for example, in jobs, life goals, relationships, and living situations.

The period of emerging adulthood is typified by both opportunities and challenges as young people transition into roles and relationships that require increased commitment and responsibility. For emerging adults who experience serious mental health conditions (SMHCs), the challenges may be particularly pronounced. Compared to their peers, emerging adults with SMHCs tend to fare worse in terms of educational attainment, career success, and community integration,2 – 4 and they are more likely to have legal troubles or become parents at a young age.5 What is more, many of the emerging adults who experience SMHC are vulnerable and/or at-risk in other ways. For example, there are high rates of SMHCs among young people in this age range who are homeless or who have had experience in the special education, child welfare, or juvenile justice systems.6 – 12

Despite the obvious need for effective services, there is growing evidence that typical services are neither attractive to nor developmentally optimal for emerging adults with SMHC.5 , 13 , 14 There is a steady decrease in mental health service utilization as adolescents approach the age of majority,14 and among adults, those in the youngest cohort are least likely to access treatment.13 , 15 Young people in their late teens and early to mid-twenties experience typical adult services as not well adapted to their needs or culture, and providers report having difficulty finding adequate age-appropriate mental health services for their clients.5 , 16 – 18 What is more, there are few programs and intervention approaches that have been specifically designed to respond to the developmental needs and challenges of this population.19 , 20 Adult providers are not usually trained in adolescent or early adult development, and so they are unprepared to work with emerging adults with SMHCs, who tend to be less developmentally mature than their age alone would suggest.5 , 14 However, there is evidence that, when age-specific services are available, utilization increases.21

Over the last decade, as evidence of the inadequacy of typical services has grown, researchers and providers have responded by describing and developing promising approaches for meeting the unique needs of emerging adults with SMHCs. One strand of this effort has focused on creating and evaluating programs and interventions that are specifically tailored to emerging adults (or “transition-aged youth and young adults,” which may include young people aged 16 and 17), or adapting approaches originally developed for children or adults.21 – 27 Another strand of effort has focused on mining the existing literature and/or securing expert consensus in order to produce guidelines or recommendations regarding core elements and service strategies that should be included in programs designed to improve outcomes for emerging adults with SMHCs or for other populations of young people (e.g., secondary students with any type of disability) among whom SMHCs occur at high rates.8 , 28 – 37

Across an important subset of these research reports, reviews, guidelines, and related documents, there appears to be a level of convergence regarding key features of practice within programs and interventions that are (in the case of research studies) or are considered likely to be (in the case of the research reviews and consensus statements) effective in improving outcomes for young people with SMHCs. These reports and reviews reference a variety of theoretical sources; however, to date there has been no comprehensive theoretical statement describing how or why positive change should occur as a result of using an approach that is characterized by the shared features. The goal of this article is to propose a general model that “backfills” a theory behind this kind of approach. The next section of the article describes the shared features of the approach and gives examples of research reports and other influential documents—including consensus statements and large-scale federal grant programs—in which these shared features are referenced. The subsequent section outlines the process that was used for developing the theory. This is followed by a section describing the theory itself and how it articulates with other key theoretical traditions in psychology and human development. The article concludes with a discussion of implications for behavioral health.

Shared Features of Interventions and Programs

As noted above, there appears to be a fair amount of agreement across a significant subset of research reports, reviews, and guidelines regarding key features that should be incorporated into interventions and programs designed to improved outcomes for young people with SMHCs. For example, there is the repeated citing of “person-centered planning” as a recommended or best practice for working with emerging adults to plan and coordinate their services and supports. While there is no universal definition in the literature regarding the precise definition of person-centered planning, essential features have been enumerated.38 , 39 A person-centered planning process is intended to support an individual with a disability to achieve the goals that are most important to him or her. The process takes its direction from the person’s perspectives, priorities, and preferences; incorporates and builds on the person’s strengths and interests; and fosters connections to community and natural supports. Frequently, the reviews, reports, and guidelines specifically emphasize the importance of a focus on empowering participants and/or building their self-determination. Beyond person-centered planning, a number of these same empirically supported programs and practice guidelines also endorse the importance of addressing multiple domains of functioning, in the manner described by Marsenich:

Increasingly, practitioners and researchers recognize that effective treatment of youth with mental illness requires more than discrete mental health treatments but involves comprehensive, integrated programs that also incorporate supportive services, including vocational training, housing, transportation, etc.19 (p. 10)

There are a number of specific examples of promising and/or empirically supported interventions and programs that have been specifically designed to improve outcomes among emerging adults with SMHCs and that are built around the shared features described above. One important example of an empirically supported approach that is built around these shared features is the Transition to Independence Process (TIP), an intervention designed specifically with this population in mind.25 , 38 TIP is implemented quite widely, having a presence in ten states (with 1 to 11 implementation sites per state) and in three regions in the province of Ontario, Canada.40 Core elements of the TIP model include person-centered planning covering multiple life domains and a focus on enhancing strengths and competencies, connections to community and natural supports, and self-determination skills. A national scan of promising programs for emerging adults with SMHCs41 presented case studies from five sites, two of which were implementing TIP. Two of the remaining three programs, while not specifically implementing TIP nonetheless provided services consistent with the shared features described above, i.e., providing individualized, person-centered planning that was based in strengths, addressed multiple life domains, and was explicitly intended to promote empowerment/self-determination. A recent study used interviews with providers who were implementing seven different empirically supported interventions—each of which had been specifically designed to serve emerging adults with SMHCs—to identify shared elements and practice principles.42 The elements and practice principles that providers held in common across these programs also reflected the shared features enumerated here.

These shared features also appear in recommendations and program requirements produced under the auspices of federal agencies. For example, the shared features appear as recommendations in the guide that was developed by the National Collaborative on Workforce and Disability for Youth (NCWD/Y), an expert panel convened by the US Department of Labor’s Office of Disability Policy to review research on evidence-based components of effective transition systems and services for emerging adults with mental health needs.31 In its listing of implications for practice, the guide recommends that direct service approaches use a person-centered approach to develop comprehensive, individualized plans. The guide further recommends that service approaches should build on the young person’s strengths and interests, and promote self-determination and empowerment. In turn, the NCWD/Y recommendations formed the basis for the interventions funded through the Social Security Administration’s Youth Transition Demonstration project, a large national study intended to test the most scientifically sound approach for supporting successful transition to adult life for youth with disabilities (a plurality of whom had mental health disabilities).29 , 43 In 2009, the US Department of Health and Human Services’ Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration funded seven states under its Healthy Transitions Initiative. The goal of the initiative was to create developmentally appropriate and effective youth-guided local systems of care to improve outcomes for youth and young adults with serious mental health conditions.44 Funded states were required, among other things, to provide direct services that focused on multiple life domains, and were strengths-based, individualized and empowerment oriented. More specifically, funded sites were encouraged to implement services using program models that were developed under a previous funding initiative, Partnerships for Youth Transition, and that were based in a person-centered planning process.45

Extrapolating from these principles and recommendations, it appears that there is a fair amount of agreement among at least a significant subset of researchers and other experts regarding core features of a cutting-edge approach for improving outcomes for emerging adults with SMHCs. What is missing across these various reports, however, is a clear statement that postulates how or why positive change should occur when the recommendations or principles are followed in practice. Perhaps this should not be surprising, given that, until very recently, theory has been very sparse in general area of positive development during young/emerging adulthood and in the more specific area of promoting positive development among older adolescents and young adults who are at-risk, vulnerable, or struggling.46 – 48

There are obvious advantages to building intervention efforts around a clear theoretical description of how and why the intervention activities actually effect change among participants.49 First, the specification of a theory of change clarifies hypotheses regarding the causal pathways that connect intervention activities to outcomes and provides information about the postulated mediators and moderators of change. This in turn promotes a clearer understanding of the relative impact of different intervention elements or activities and facilitates the interpretation of both significant and non-significant findings from research and evaluation.50

A clearly articulated theory of change is also important for helping staff understand how desired outcomes are promoted by the interactions and activities that they undertake with their clients. In other words, the theory helps staff to identify the “active ingredients” of their practice and, presumably, to utilize these more intentionally and effectively. Helping staff come to an understanding of pathways to change is important for any intervention,51 – 53 but may be particularly crucial for comprehensive interventions that provide services and supports that are highly individualized. In contrast to interventions that are more tightly scripted, individualized interventions typically require providers to be flexible in implementing elements and activities. An awareness of the theory of change can facilitate practitioners’ decision making about when and why to implement a given activity or element. The theory thus acts as a guide to achieving “flexibility within fidelity”54 and facilitates providers’ discretion in drawing on an intervention’s active ingredients under complex decision contexts. Theoretical understanding informs providers’ decisions about selection, sequence, and pacing as they deploy their repertoire of diverse intervention tools.

Finally, the identification of a general theory of change may have a further advantage in the context of interventions for emerging adults with SMHCs, by allowing the interventions as a group to be conceptualized in terms of a framework of common elements and common factors.55 Meta-analyses of outcome studies of psychotherapy among adults have provided evidence for the existence of common factors—i.e., features of provider-client interpersonal processes or a general practice “mode”—that are important for engaging clients in purposive collaboration and that are highly determinative of outcomes regardless of the specific treatment model being used.56 Another strand of research, emerging from the field of children’s mental health, has identified practice elements—i.e., discrete, defined activities or procedures—that are common across the treatment protocols of a large number of evidence-based and empirically supported interventions.57 , 58 Recently, efforts have been made to draw together the work on common factors and common elements as a way of capitalizing on findings from a pool of related research studies and drawing guidance about how to maintain “flexibility within fidelity” while also tailoring treatment in a highly intentional manner, so as to respond to clients’ diverse strengths, needs, and life circumstances.55 , 57 , 59

As noted previously, a core feature shared across many of the reports cited previously is the use of person-centered planning as a way of individualizing treatment and organizing selected services and supports for emerging adults with SMHCs. The planning process thus represents a core of common elements—i.e., procedures or activities—that is shared across interventions. Similarly, the set of commonly endorsed principles points to the existence of common factors—i.e., a general practice mode that describes how providers collaborate with young people to promote growth and change. Explicitly formulating these shared procedures/activities and principles in terms of common elements and common factors may make it easier to capitalize on what is being learned in research, evaluation, implementation, and practice, allowing insights gained in one context to be more adeptly applied in another, and perhaps stimulating a more rapid growth in knowledge about effective ways to promote positive outcomes in an area where empirical evidence is currently limited.

Developing the Theory

The goal of the work described in the remainder of this article was to propose a general model or theory of change that would incorporate the core of shared factors and elements that appear frequently across the sources described earlier. The intention was to describe how and why these features might come together in practice and, as a result, promote desired outcomes for emerging adults with SMHCs. In other words, the idea was to “backfill” a theory behind what appears to be an increasingly popular approach to working with this population. As noted previously, this kind of theory can be useful in formulating research and interpreting findings, and it can be an asset to human resource development. Additionally, a clearly articulated model can aid not only in work that confirms the importance of various features of the model but also in work that disconfirms or questions the assumptions that it contains. The model presented here is thus not envisioned as an endpoint, but rather as an effort to summarize and clarify an approach to working with emerging adults that, for reasons given below, the authors characterize as a “positive developmental” approach.

The model was developed over the course of several years, using a multi-step process that has been described in detail in a previous publication.60 The first iteration of the model was informed primarily by a review of the literature described above. The resulting model was written up and circulated internally, to staff at the Research and Training Center for Pathways to Positive Futures (Pathways RTC), a federally funded center comprising eight research projects and related dissemination, training, and technical assistance activities, all focused on improving outcomes for emerging adults with SMHCs. The research at Pathways RTC includes intervention studies, and as a result, the staff includes direct service providers, some of whom are peer mentors who have experienced SMHCs. Staff feedback thus included the perspectives not just of researchers but also of providers and of young people who had themselves been clients of mental health and related service systems. Staff members were asked to read the model document and then met as a group for discussion. Eight staff members also provided detailed written feedback.

After feedback from staff was incorporated, the revised theory was circulated to a set of ten nationally recognized experts outside of Pathways RTC. These included specialists whose work focused on development during emerging adulthood, as well researchers who had created and tested interventions. Additionally, feedback was sought from providers and administrators in programs that implemented empirically supported interventions for emerging adults with SMHCs. Finally, feedback was also sought from young people and family members who were active at a national level in efforts to improve services and systems for emerging adults with SMHCs.

At the same time as the expert review was underway, Pathways RTC staff was conducting a series of semi-structured interviews with young people and providers.42 Participants in the interviews were drawn primarily from agencies implementing the empirically supported interventions cited previously. (Participants were also recruited from a culture-specific program that had demonstrated positive outcomes in unpublished evaluation reports.) Attempts were made to engage at least one provider and young person from each intervention cited previously; however, several interventions could not be represented because they had been implemented as grant-funded experiments and were no longer active. Ultimately, 11 providers and 7 young people were interviewed. The interviews focused on eliciting participants’ reflections on the practice principles and elements that had been extracted from the literature. Particular emphasis was placed on eliciting specific practice examples that illustrated what providers did to realize the principles in their work with young people. Emphasis was also placed on understanding participants’ own theories regarding how these practice elements contributed to desired outcomes. This latter focus—which was also a key aim of the feedback sought from administrators in empirically supported programs described above—was particularly important since the theoretical and empirical literature offered little detail that specifically described the causal linkages between practice principles and practice activities, and outcomes.

The theory was then revised yet again, incorporating and responding to the expert feedback and the information gained through analysis of the interview material. A description of this version of the theory was circulated to participants who had been invited to attend Pathways RTC’s state-of-the-science conference, held in May 2013.60 The conference was attended by representatives of various stakeholder groups, including researchers, practitioners, and administrators. (A list of attendees is provided in the appendices to the conference proceedings.) More than a quarter of the attendees were systems-experienced young adults who had received treatment for SMHCs and related needs. Parents and other family members were also well represented. Over the course of the one-and-a-half day conference, attendees participated in a series of structured small- and large-group work sessions focused on specific aspects of, or questions arising from, the proposed theory of change. Proceedings from the conference provide detailed information on the precise nature of the feedback provided by participants, as well as the methods used for eliciting that information.60 The version of the model that emerged after incorporating participants’ feedback and ideas was considered ready for wider dissemination.

In essence, the theory describes an intervention model in which a provider guides young people through a process designed to help them learn to drive their own development toward the future they aspire to and the goals and roles they find personally meaningful—i.e., to find a path to a future they desire. Referencing this process, Pathways RTC and the positive developmental approach more generally, the theory of change is referenced from here on as the “Pathways to Positive Futures model” or “Pathways model” for short.

Positive Development in Emerging Adulthood

In general, the purpose of positive development interventions is to optimize developmental processes and to increase thriving for people who are struggling, at-risk, and/or experiencing challenges or poor outcomes. In other words, positive development interventions seek to restore and/or enhance the same developmental processes that drive maturation and growth for “typically developing” peers who do not experience such daunting levels of challenge. The Pathways model thus builds on existing theories of positive development during late adolescence, young adulthood, and emerging adulthood to describe optimal developmental processes. The Pathways model also describes intervention elements and provider factors (i.e., the provider’s mode of practice) and how these come together to restore or enhance positive development for young people whose developmental trajectory has been adversely affected by SMHCs and related challenges.

Though contemporary theories that describe positive development during the later teens and twenties do not express a unified vision of exactly how development occurs, they do contain a core of similarity. Generally speaking, these theories are derived from the premise that if young people are connected through mutually beneficial relationships to people and institutions in their social environments, and if young people are encouraged through those relationships to develop their skills and abilities, then they will be set on a trajectory leading to a future in which they will promote thriving within themselves and those around them. The theories tend to draw on a set of broader psychosocial developmental theories and concepts, which are then used to describe the dynamics that drive development toward the emergence of a mature adult identity and the acquisition of skill in the key competency areas of emerging adulthood: educational/vocational, social, romantic, and civic. In general, these key developmental outcomes are not that different from those that have been associated with adolescent development in the past; however, there is recognition that, particularly given the contemporary phenomenon of a lengthening period of transition to mature adulthood, work on these tasks and competencies is typically initiated during adolescence but not completed until later.61 – 65

There are two main sets of theories that form the core of descriptions of positive development during the late teens and twenties.47 , 61 , 63 – 70 The first set includes ecological development theories and related systems theories and, to a lesser extent, theories related to social networks and social capital.65 , 71 – 74 These theories focus on the way that individuals are embedded in and interact with their life contexts or “systems.” These systems include the self and more intimate contexts such as family and peers, as well as community groups and organizations, and larger socio-cultural contexts. Development is stimulated through feedback loops of communication, exchange and causality between the individual and his contexts, and progresses by means of an ongoing process of rebalancing, with the maintenance of stability and identity on one side, and the adaptation to or desire for change on the other.47 , 75 Positive or optimal development is characterized by adaptive or mutually beneficial relationships between an individual and her life contexts, so that the individual contributes to the contexts that support her.47 , 76 , 77

The second set of theories focuses on emerging adults’ evolving capacity to direct their own development and the acquisition of skills for doing so. These relatively abstract skills for directing one’s own development are referred to here as “meta-developmental” skills. Key skill areas include setting personally meaningful goals, making plans and taking action steps toward the goals, and managing the outcomes of goal-directed efforts by adjusting goals and or plans over time.64 , 67 , 68 , 78 , 79 Managing this process requires not just the ability to plan and carry out goal-directed activity; it also requires the ability to manage the cognitions and emotions that arise around success and failure, as well as those that come up as a young person confronts uncertainties and shifts of perspective that are inherent in planning for the future. As a person gains confidence in his general ability to realize valued outcomes, his self-efficacy, self-determination, empowerment, and/or hope increase. Indeed, each of these overlapping constructs has been linked to positive outcomes for emerging adults.46 , 68 , 76 , 80 – 82

These two sets of theories are drawn together here to describe positive development in emerging adulthood. The merging of theories is accomplished by pointing out that, as young people mature and gain experience with different life contexts, they also gain skill in managing connections to contexts, understanding of the kinds of competencies that are needed to function competently in different contexts, and knowledge regarding the extent to which various contexts fit with their goals and aspirations for the future.47 , 68 , 83 , 84 In turn, this allows them to manage decisions related to whether and how to engage with—and commit to—different life contexts, and how to align their own strengths, needs, and values with those of various contexts. It also allows them to be intentional in pursuing specific skills—including educational, vocational, interpersonal and intrapersonal skills, and skills for self-care and wellness promotion—that they need in order to function competently in the contexts of their lives.

Thus, through the years of emerging adulthood, young people are engaged in ongoing processes in which goal-directed activity and connections to contexts interact in ways that promote the emergence of a mature identity. In turn, identity is supported and stabilized through enduring commitments to people, contexts, values, and longer term life goals. When development is proceeding optimally, the result is what can be described as a “virtuous cycle” of positive development, with growth in one area promoting growth in others: The young person reaches adulthood with a stable sense of his own identity and with the competencies and skills needed to undertake valued roles in the contexts that support that identity. Assuming roles in valued contexts and accomplishing age-related milestones contribute to perceptions of self-respect, well-being, and quality of life.

Positive Development for Emerging Adults with SMHCs

The virtuous cycle of positive development during emerging adulthood is depicted on the right-hand side of Figure 1. This section of the article proposes a description of how the provider factors and intervention/program elements that characterize a positive developmental approach (shown on the left-hand side of the figure) come together to propel the cycle. The section begins with a description of the outcomes associated with the positive developmental cycle and their interconnection. Attention then shifts to a description of the intervention/program elements and the provider factors. The section ends with a description of process outcomes—i.e., the shorter term outcomes that can be assessed to determine the extent to which the elements and factors are being implemented successfully as providers work with young people.

Work to develop the Pathways model supported the virtuous cycle’s overall relevance in the conceptualization of projects and interventions that use a positive developmental approach for working with young people with SMHCs. The sets of outcomes that are part of the cycle (meta-developmental skills, role- and context-related knowledge and skills, positive connections to contexts, maturity) are quite consistent with the literature on programs and interventions for the population described previously. For example, a person-centered planning process is clearly an opportunity for young people to practice and learn the skills needed for driving development. Outcomes sought by the programs include skills necessary for, and competence in, various contexts. Most typically, these are educational/vocational skills for job/career competence and wellness-related skills for supporting mental health and maintaining personal safety. Increases in empowerment, self-efficacy, or self-determination were also mentioned fairly often.

Feedback from expert stakeholders and interviewers with providers and young people provided additional detail and nuance about each of the outcome areas and the dynamics of the developmental cycle for emerging adults with SMHCs.42 , 60 For example, most providers were quite explicit in seeing their roles as being centrally concerned with helping young people acquire meta-developmental skills. A number of providers also described in great detail their efforts to help young people understand and manage their connections to contexts of family, peers, and culture. Providers described the ways they supported young people to negotiate their roles in and across these contexts so that the connections were positive (i.e., mutually beneficial as described above) and supportive of their emerging life goals. Providers noted that this can be particularly challenging when the values and expectations of different contexts are incompatible to some extent. Young people and providers in culturally specific programs had a somewhat unique focus on the importance of values and commitments in helping emerging adults build mature, positive identity amid the challenges of competing values from various contexts. Young people themselves placed particular emphasis on the importance of skills and knowledge for maintaining holistic mind/body wellness given the challenges presented by medications and by a SMHC itself. Both young people and providers noted the positive developmental consequences of gaining skills for and engaging in advocacy to improve mental health and related services and systems. They also stressed how peer groups of young people with SMHCs could be intentionally organized to function as important positive developmental contexts, with group members providing hope and inspiration, and acting as role models, mentors, and advocates for one another.

As noted previously, the general intention of positive developmental interventions is to restore or enhance developmental processes that have been compromised by high levels of risk and challenge. Ample evidence exists showing that emerging adults with SMHCs tend to lag behind their peers in attaining each of the types of outcomes included in the Pathways model.3 , 22 Importantly, young people who have received intensive services and/or had out-of-home placements as children and adolescents often have had few opportunities to develop meta-developmental skills, since these types of services tend to be crisis driven, reactive, and highly compliance oriented. Additionally, many of these systems-experienced young people have histories of trauma, which can lead to extreme difficulties in forming and sustaining positive connections to people and contexts. Finally, for young people who first experience psychosis or other SMHCs during the period of emerging adulthood, deep wounds to identity and severe attrition in connections to contexts are typical. In sum, for emerging adults with SMHCs, the cycle of development can begin to function in what could be characterized as a vicious cycle, with young people growing progressively less connected to positive contexts, failing to develop skills and knowledge needed for adult functioning, and becoming demoralized, passive, and/or reactive.

Common Elements and Common Factors

The discussion here of common intervention/program elements and provider factors relies to a great extent on the information provided by individuals with direct experience with positive developmental interventions or programs that incorporate the core shared elements and factors described previously. The descriptions that are offered are thus the product of distillation and interpolation of material from the interviews, commentary, and feedback that was gathered in the process of developing the model,42 , 60 rather than a summary or synthesis of previously existing theory or research. This approach was required because the existing theoretical and empirical literature related to the general positive developmental approach being described here does not offer much specific detail regarding exactly how practice elements and factors actually contribute to outcomes.

Intervention/program elements

The left-hand side of Figure 1 is intended to depict the coming together of the common intervention/program elements (formalized activities, procedures or “pieces” of an intervention) and provider factors (a principle-driven mode of interaction) as providers work collaboratively with young people with SMHCs to restore or enhance the positive developmental cycle. Regarding intervention elements, the main steps of a structured, person-centered process for making and carrying out plans are quite consistent across interventions, and most typically include envisioning a desired future, developing medium-term goals and short-term activities or action steps consistent with the vision, carrying out the activities, reviewing progress, celebrating success, adjusting goals, and so on. The provider, who is typically thought of as a coach or facilitator, supports this process with collaboration and consultation, using knowledge about the young person’s life contexts; community resources and social support/social capital development; and support strategies to help the young person create and carry out activities that have a good chance of being successful. In some cases, the young person (and the coach or facilitator) works with a larger team to develop and implement the whole plan or specific portions of the plan. The intervention may encourage the young person to focus primarily on a single or small number of life domains (e.g., career development), or the intervention may be more comprehensive and have a broader focus, with young people considering a variety of life domains and prioritizing one or more for attention.

Other shared intervention elements are clearly connected to the set of shared practice features outlined previously. For example, consistent with the characterization of interventions as “strengths based,” they typically include some kind of strengths exploration that takes place early on. The strengths exploration is a semi-structured conversation between the provider and the young person, during which the provider draws out and highlights personal strengths and assets that the young person may or may not have identified previously. In some cases, information regarding strengths and assets is also solicited from other people who know the young person well. Information on strengths is incorporated into a strengths list or inventory, which is then systematically referenced and updated as the intervention unfolds. For example, activities that are developed for the plan may be explicitly designed to draw on strengths listed in the inventory. Additionally, the provider may engage the young person in structured debriefing after activities are undertaken, in order to draw out information about the strengths that were used in or revealed by the activities.

Another key shared element reflects the attention that is placed by positive developmental interventions on facilitating connections to supportive life contexts. In a manner similar to that used for strengths, the provider often begins early in the intervention to explore sources of social support/capital that are available or potentially available to the young person from a very wide variety of individuals, groups, organizations, and institutions. This inventory of available support is then continually referenced and updated throughout the planning process, and activities that are developed for the plan are designed explicitly to draw on, create, build, or strengthen positive connections.

Stakeholders and interviewees also pointed out how certain key intervention elements—i.e., procedures or processes—are systematically repeated over time, as a means of explicitly teaching young people meta-developmental skills that can be applied not just within the intervention but outside it as well. For example, several interventions include a specific set of steps for decision making. When difficult decisions come up, providers coach the young people through this procedure, which is designed to help them more fully consider the ramifications of different courses of action for themselves and others over both the shorter and longer term. Providers noted that they encouraged young people to use this decision-making procedure regardless of whether or not the provider was present. Other repeated elements include procedures for developing goals that are personally meaningful, figuring out where to begin work on large or complicated goals, evaluating goal-directed efforts, remembering to celebrate success, and so on.

Provider factors

In addition to common intervention elements—steps, procedures, etc.—positive developmental approaches are also characterized by provider factors, i.e., principles that describe how providers should interact with emerging adults. Principles are intended to guide providers’ practice at all times, regardless of the specific element of the intervention that is being undertaken. Providers pointed out that, for example, it is clearly possible to go through the steps of the planning process in a way that does not prioritize the perspectives of the emerging adult, as would be necessary in if the planning were truly person centered. The Pathways model thus assumes that principles will be consistently applied across the intervention elements, with result that momentum is contributed to the cycle of positive development.

The first principle requires that the provider works in a way that promotes trust. A central part of promoting trust is being transparent with the young person and not attempting to coerce or manipulate her. It also includes consistently modeling hopefulness and positive energy, and being reliable and following through with commitments. Though trust is a fairly abstract concept, providers and young people were quite specific about the kinds of things providers could do to build it. Trust is widely seen by providers and young people as an essential component for building the kind of relationship that allows the collaborative work of the intervention to take place.

The second practice principle affirms that the work of the intervention is to be driven by the priorities and perspectives of the young person. This means that the provider needs to have considerable skill in drawing out what is meaningful and motivating to the young person, helping him to clarify perceptions and priorities, and to identify feelings of conflict, ambivalence, or ambiguity. Doing this requires patience, skill, and self-awareness, so that the provider can elicit and clarify without (intentionally or unintentionally) trying to replace young people’s ideas and perspectives with her own.

The next principle reinforces the idea that the provider is explicitly focused on helping the young person learn and practice the meta-developmental skills so that he gains an increased sense of confidence, competence, and self-efficacy. As a result, instead of simply moving the young person through a planning process, the provider is equally if not more focused on teaching skills (e.g., the procedure for making difficult decisions described above) and helping the young person get a sense of when to use which skills and how to combine various skills and steps into efforts to move toward valued goals and outcomes. Thus, the intervention is less about creating a good plan (though a good plan is also important) than it is about practicing planning as a way to help young people gain confidence in their own ability to make progress toward a positive future.

Another principle requires that the provider is able to take a “motivational” approach that helps the young person come to understand and experience himself in new ways. The use of “motivational” in this context is akin to—though also distinct from—its usage in an evidence-based counseling approach called Motivational Interviewing (MI).85 While MI is considered a client-centered counseling style, it is more directive than traditional client-centered approaches because the therapist has an intentional bias toward helping the client to explore and make specific kinds of behavioral changes. The use of “motivational” in the Pathways model preserves this central idea of the provider as being simultaneously client-centered and intentionally biased. However, in the Pathways model, this idea is applied quite broadly, since providers are motivational not just about supporting behavior change (i.e., helping young people become more proactive in their own lives) but also about supporting non-behavioral change, including change in self-concept, identity, and social cognition. Thus, while maintaining a client-centered stance, the provider is also intentionally biased in helping young people understand themselves and their contexts in ways that help engage and sustain the virtuous cycle of positive development.42

Striving to be both client-centered and intentionally biased may appear as a contradiction; however, the point is to use the young person’s own perspective as the basis for “bias.” The provider is at pains not to be—and not to give the appearance of being—manipulative or coercive. It is therefore important for providers to be conscious and transparent with the young person about exactly what they are being biased toward, and to be able to communicate this clearly to the young person during the early stages of the intervention (e.g., by explaining transparently the point of the program or intervention, the outcomes, how it will unfold, the role of the provider in supporting development and change, etc.). This sets the stage for the provider to be transparent about “motivational” comments or reflections made later on, by explicitly reminding the young person of how a particular aspect of the work fits within the parameters of the intervention.

For example, the Pathways model describes providers as being “motivational” toward building perceptions and experiences of strengths and competence. This means that the provider is intentional in working with the young person to draw out authentic talk about personally meaningful strengths, skills, successes, and accomplishments; to facilitate opportunities to develop and use these strengths; to recognize success, growth, and accomplishments, even when they may not be obvious; to explore how strengths can and do contribute to accomplishments; and to explore and resolve ambivalence related to having, developing, and/or using strengths. The provider is able to allow the young adult’s perspectives and priorities to emerge while also guiding and channeling the process by selectively drawing out, working with, and reinforcing certain things the young person says and does. The provider is thus mildly but intentionally biased, motivational, or directive—at all times alert and attuned to opportunities to make specific kinds of reflections or summaries or connections between things the young person has said. In short, the central purpose behind this focus on strengths and competence is to help the young person increase his understanding of himself as someone who can do things that are intrinsically meaningful, or that help in achieving meaningful goals or making positive contributions to contexts.

The provider is also biased and motivational toward acknowledging, building, and bolstering the young person’s positive connections to contexts, including individuals, groups, organizations, and institutions whose values and impact are consistent with the young person’s vision for himself and his life. The provider is continually alert to the young person’s mentions of contexts that could support his positive development and to opportunities for the young person to experience contributing positively to valued contexts. Providers also help young people learn about and plan for acquiring the skills they need to function in these valued contexts. For example, providers are aware that families are often key contexts for young people’s lives. But they are also aware that relationships between young people with SMHCs and their families are often strained, conflictual, or even completely ruptured. Providers thus take a motivational approach in exploring young people’s connections to their families and the possibility of undertaking activities intended to strengthen those relationships. In other words, the provider works intentionally with the young person’s own ideas and perspectives to probe and question, exploring motivation and resistance without in any way trying to dictate what the young person should feel or do. Should the young person decide to work on building his family connections, the provider may work with him to plan meetings or activities with family members (with or without the provider in attendance to facilitate the occasion or support the young person), with the intention of problem solving, improving communication, or otherwise strengthening relationships. Part of this work may include coaching the young person in specific skills for handling uncomfortable topics or situations in a productive way.

A further area of “bias” is toward expanding the young person’s boundaries of competence. In other words, the provider works to understand the young person’s existing level of capacity—often referred to as “starting where they’re at”—and supports the young person to undertake activities in ways that challenge or stretch her level of skill. The provider may give active support at first but has the goal of withdrawing that support so that the young person can function independently and increase her confidence, knowledge, or skill. In particular, the provider works to expand competence in the use of meta-developmental skills by providing tools (such as the process for making decisions described previously), modeling and teaching their use, and structuring opportunities to use them. Providing this kind of support can be quite intricate, since young people have very individualized patterns in the level of development of different skills. The general vision for providing this kind of support is not new, of course, and is quite typical of more general Vygotskian approaches to teaching and learning,86 including adult learning. More recent work in positive psychology has shown that working at the edge of existing competence tends to produce positive affect and enhance intrinsic motivation.87

Finally, providers are motivational toward discovery and activity. “Activity” in this context simply refers to doing something (versus nothing), while “discovery” refers to generating opportunities to explore something new. This exploration may or may not have any immediate practical or pragmatic purpose, but serves the more general goals of (1) engaging motivation and exposing the young person to a wider range of ideas and life experiences, and (2) helping the young person become used to the idea of taking on and overcoming healthy risks, for example by going to a new place, or meeting, or talking to a new person.

Process outcomes

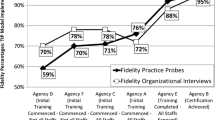

As work progresses, process outcomes can be tracked to provide evidence about whether or not the intervention or program is being carried out as intended. The Pathways model proposes two general types of process outcomes that can be monitored as a way of assessing the extent to which a provider is being successful in implementing and blending the elements and factors. The first type of process outcome focuses on whether or not providers are actually carrying out the intervention elements, and doing so in a way that reflects the factors/principles. This sort of fidelity to the intervention elements and provider factors can be assessed using data gathered in a number of different ways, for example, through the use of in-person, video, or audio “observations” of the provider at work; through confidential surveys or interviews conducted with clients; through structured debriefing of providers; and/or through the examination of documentation related to the provider’s work with young people. It is likely that a combination of these methods would be optimal—and that the inclusion of some form of observation would be necessary—so as to get an accurate assessment of the “dose” of intervention elements delivered as well as the consistency of principle-adherent practice.

The second type of process outcome focuses on what the young person is doing and learning as the intervention unfolds. For example, it is important to know whether the young person is actually engaging in activities that she believes are connected to her longer term aspirations, and whether these activities are helping her to build connections to contexts and to acquire the knowledge and skills required to function competently in those contexts. This type of process outcome would also include a focus on the extent to which the young person has an explicit awareness of her own growing competence, both in the use of meta-developmental skills and in specific areas of activity.

The various reports cited earlier that describe or recommend a positive developmental approach for working with young people with SMHCs do not generally focus much attention on process outcomes, and no instance was found of a strategy for assessing process outcomes (either in research studies or in community practice) that included observation of providers’ work. Two observations emerging from the work to develop the Pathways model60 might help explain this apparent lack of attention to process outcomes. The first observation is that there was a lack of clarity among providers and program implementers regarding how to concretely describe or objectively recognize principle-adherent practice (i.e., practice in which provider factors were demonstrated). The second observation is that these stakeholders could only describe a fairly small number of practice elements, and that most of these were associated with the early engagement phases of interventions. Taken together, these two observations suggest that provider factors and program elements—and importantly, how these intersect in ongoing practice—remain incompletely conceptualized, which in turn makes them difficult to measure. Developing clearer conceptualizations of process outcomes, and better strategies for measuring them, is important not just for research purposes, but for ongoing implementation, so that providers and other stakeholders can know whether or not the program elements are being implemented correctly and in sufficient dose, and whether providers are able to consistently interact with young people in a principle-adherent manner.

Implications for Behavioral Health

Feedback gathered during the process of developing the Pathways model supports the idea that the model appropriately represents what participating stakeholders believed providers should do to implement a positive developmental approach in their work with emerging adults with serious mental health conditions. However, it does not necessarily follow that all of the assumptions contained in the model are true, that this is the only type of approach that can produce positive outcomes, or that the model is a complete description of what providers can or should do to promote positive development among young people in this population. Testing the model’s assumptions and exploring its limitations will be key strands of work in further efforts to develop and refine the model—or even to restructure or replace it, depending on the results of future inquiry.

Fully testing the assumptions contained in the model will require gathering and analyzing a variety of types of outcome data, including mental health status and functioning in different domains—e.g., employment, education, and community living—as well as other longer term outcomes—e.g., those related to positive connections to contexts, development of meta-developmental skills, and levels of well-being or quality of life. Crucially, testing the model will require improved conceptualization and operationalization of process outcomes—including fidelity to program elements and provider factors/principles—in addition to gathering and analyzing data to measure them.

As described near the beginning of this article, the shared features characteristic of a positive developmental approach appeared across a number of research reports, consensus statements, and informal reviews. However, it is useful to consider implications arising from the fact that some of the sources did not reference all or even any of these features. This suggests an important limitation of the Pathways model, namely that it is only one possibly effective approach, and that approaches built around different sets of key elements and/or factors have also been successful in improving outcomes for this population. This does not necessarily undermine the potential usefulness of the Pathways model, since certainly it is possible that there are multiple ways to work productively with the population, and/or that different approaches are effective with different sub-populations. Further work is needed to explore in detail whether there are specific findings or recommendations in these other reports that would contradict or undermine assumptions within the Pathways model, or that could be incorporated into the Pathways model to improve and enrich it.

The literature review undertaken at the outset of this work turned up several practice features that were referenced in multiple sources, though these were not referenced as frequently as the shared features that are referenced repeatedly in this article. These features point both to potential limitations of the Pathways model and to possible implications for behavioral health.

One of these features was encouraging and supporting civic participation, particularly including participation on boards and advisory committees that make decisions and create policy regarding services and supports provided to emerging adults. This recommendation is clearly related to a key theme from both the positive development and disability policy literatures,70 , 88 namely, that efforts to improve outcomes should not rely exclusively on changing the individual (e.g., a program or intervention participant), but should also focus on changing social, community, and service environments so that they are more supportive of individuals’ social integration and well-being. This also resonates with a theme from emerging adults’ personal experiences that was prominent in conference discussions focused on the Pathways model.60 The young people in attendance stressed the benefits they had experienced in their own lives as a result of opportunities both to change existing environments—for example through legislative advocacy or participation on policy-making committees at the agency, local or state levels—and to create completely new environments—e.g., drop-in centers and leadership programs run by and for emerging adults with SMHCs. The Pathways model as currently constituted includes a reference to building positive connections to society and skills for civic participation; however, this aspect of the model is not well developed and should be considered as a limitation. More research on the ways in which emerging adults’ lives are enhanced as a result of changing their environments is clearly needed, and could help to clarify whether work that targets changing the environment is best promoted by enhancing this focus within existing programs or interventions, and/or by creating entirely new ones.

Another feature that was referenced in multiple reports was providing services and supports in a manner that is accommodating toward and supportive of the young person’s culture(s). The Pathways model lacks a specific focus on cultural appropriateness, and this must be considered as a limitation. Theories that include a focus on self-determination and related constructs—as the Pathways model does—have been criticized on the grounds that they are relevant only within individualistic cultures (typically contemporary mainstream Western cultures), and not within more traditional or collectivist (sub)cultures.81 , 89 – 92 While this controversy persists, proponents of theories that see the development of agency and skills for goal-directed activity as a key features of successful maturation cross-culturally have presented various arguments pointing to the relevance of these features even outside of mainstream Western culture.79 , 87 – 89 An important aspect of this literature is that it presents a more nuanced view of exactly what agency or self-determination means, and an appreciation of these subtleties might be helpful for providers using Pathways-like approaches with emerging adults from diverse cultures. This controversy is far from settled, however, and other researchers and theorists have presented well-founded arguments that express skepticism regarding the appropriateness of applying self-determination theory to work with individuals in more traditional or non-Western (sub)cultures.92 Until further research is undertaken, it will be difficult to know the extent to which the approach described in the Pathways model is appropriate or helpful for young people from diverse backgrounds. Fortunately, emerging theory and research is beginning to provide guidance to the field regarding when and how empirically supported interventions should be adapted for use in diverse cultural contexts.93

It is important to point out that the Pathways model is based on a review of literature that focused almost exclusively on only a subset of interventions, namely those that rely on a professional provider to develop a trusting relationship with a client and, working through that relationship, to be the facilitator of change in the client’s life. While this is certainly a very common approach to behavioral health intervention in the USA currently, there are other intervention modalities that are producing promising results, that are consistent with a positive developmental approach, and/or that are in high demand among young people with SMHCs. These other modalities take very diverse forms, such as, wellness programs (e.g., meditation, yoga, exercise, diet, and recreation), computer-mediated interventions, group interventions (including self-help groups), and various forms of peer support and mentoring. Whether and when Pathways-type interventions are the most appropriate and/or cost effective—or if they should be offered in combination with other interventions—depends on research that examines a full spectrum of support, treatment and care modalities.

Finally, it is also important to note that Pathways-type interventions will encounter great difficulty in helping young people achieve positive outcomes unless the larger context—including the service system and the policy and funding environment—promotes opportunities and provides the kinds of resources that allow young people with SMHCs to meet their basic needs and make progress on goals they have prioritized. Pathways-type interventions and programs will likely have the greatest chance of success in communities in which stakeholders work together to provide young people access to, for example, safe places, affordable education and housing, job opportunities and employment support, health care, and complementary services such as specialty mental health services, drug and alcohol treatment, and medication management.94

References

Arnett J. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist 2000; 55(5): 469–480.

Davis M, Banks S, Fisher W, et al. Longitudinal patterns of offending during the transition to adulthood in youth from the mental health system. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research 2004; 31(4): 351-366.

Davis M, Vander Stoep A. The transition to adulthood for youth who have serious emotional disturbance: Developmental transition and young adult outcomes. Journal of Mental Health Administration 1997; 24(4): 400-426.

Vander Stoep A, Beresford S, Weiss N, et al. Community-based study of the transition to adulthood for adolescents with psychiatric disorders. American Journal of Epidemiology 2000; 152: 352-362.

US Government Accountability Office. Young adults with serious mental illness: Some states and federal agencies are taking steps to address their transition challenges. GAO Publication No. 08-678, Washington DC: Author, 2008.

Courtney ME, Dworsky A. Midwest Evaluation of the Adult Functioning of Former Foster Youth. Chicago: The University of Chicago, Chapin Hall Center for Children, 2005.

Garland AF, Hough RL, McCabe KM, et al. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in youths across five sectors of care. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2001; 40(4): 409.

National Collaborative on Workforce and Disability. Guideposts for Success, Second Edition. Washington DC: Institute for Educational Leadership, National Collaborative on Workforce and Disability; 2013.

James DJ, Glaze LE. Mental Health Problems of Prison and Jail Inmates. Washington DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2006.

Shufelt JL, Cocozza JJ. Youth with Mental Health Disorders in the Juvenile Justice System: Results from a Multi-State Prevalence Study. Delmar, NY: National Center for Mental Health and Juvenile Justice, 2006.

Unger JB, Kipkke MD. Homeless youths and young adults in Los Angeles: Prevalence of mental health problems and the relationship between mental health and substance abuse disorders. American Journal of Community Psychology 1997; 25(3): 371.

Vander Stoep A, Beresford S, Weiss N, et al. Community based study of the transition to adulthood for adolescents with psychiatric disorders. American Journal of Epidemiology 2000; 152: 352-362.

Kessler RC, Demler O, Frank RG, et al. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders, 1990 to 2003. New England Journal of Medicine 2005; 352(24): 2515-2523.

Pottick KJ, Bilder S, Vander Stoep A, et al. US patterns of mental health service utilization for transition-age youth and young adults. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research 2008; 35(4): 373-389.

U.S. Department of Human Services Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. What a Difference a Friend Makes: Social Acceptance is Key to Mental Health Recovery. SMA 07-4257, Washington DC: National Mental Health Anti-Stigma Campaign, 2007.

Davis M. Pioneering Transition Programs; The Establishment of Programs that Span the Ages Served by Child and Adult Mental Health. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, 2007.

Jivanjee P, Kruzich J, Gordon L. Community integration of transition-age individuals: Views of young adults with mental health disorders. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research 2007; 35(4): 402-418.

Sieler D, Orso S, Unruh, DK. Creating options for youth and their families. In: HB Clark, DK Unruh (Eds). Transition of Youth and Young Adults with Emotional or Behavioral Difficulties: An Evidence-Based Handbook. Baltimore: Brookes Publishing, 2010, pp. 117-140.

Marsenich, L. A Roadmap to Mental Health Services for Transition Age Young Women: A Research Review. Sacramento, CA: California Institute for Mental Health, 2005.

Lane KL, Carter EW. Supporting transition-age youth with and at risk for emotional and behavioral disorders at the secondary level: A need for further inquiry. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders 2006; 14: 66-70.

Gilmer TP, Ojeda VD, Fawley-King K, et al. Change in mental health service use after offering youth-specific versus adult programs to transition-aged youths. Psychiatric Services 2012; 63(6): 592-596.

Walker JS, Gowen LK. Community-Based Approaches for Supporting Positive Development in Youth and Young Adults with Serious Mental Health Conditions. Portland, OR: Portland State University, Research and Training Center for Pathways to Positive Futures, 2011.

Hagner D, Malloy JM, Mazzone MW, et al. Youth with disabilities in the criminal justice system: Considerations for transition and rehabilitation planning. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders 2008; 16(4): 240-247.

Powers LE, Geenen S, Powers J, et al. My Life: Effects of a longitudinal, randomized study of self-determination enhancement on the transition outcomes of youth in foster care and special education. Children and Youth Services Review 2012; 34(11): 2179–2187.

Haber, MG, Karpur A, Deschenes N, et al. Predicting improvement of transitioning young people in the partnerships for youth transition initiative: Findings from a multisite demonstration. Journal of Behavioral Health Sciences and Research 2008; 35(4): 488-513.

Melton RP, Roush, SN, Sale, TG, et al. Early intervention and prevention of long-term disability in youth and adults: The EASA model. In K Yeager, D Cutler, D Svendsen et al. (Eds). Modern Community Mental Health: An Interdisciplinary Approach. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013, pp. 256-275.

Gowen LK, Bandurraga A, Jivanjee P, et al. Development, testing, and use of a valid and reliable assessment tool for urban American Indian/Alaska Native youth programming using culturally appropriate methodologies. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work 2012; 21(2): 7-94.

Cobb RB, Lipscomb S, Wolgemuth J, et al. Improving Post-High School Outcomes for Transition-Age Students with Disabilities: An Evidence Review. NCEE 2013-4011, Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, US Department of Education, 2013.

Fraker T, Rangarajan A. The Social Security Administration’s Youth Transition Demonstration Projects. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 2009; 30: 223–240.

Blau GM, Caldwell B, Fisher SK, et al. The Building Bridges Initiative: Residential and community-based providers, families, and youth coming together to improve outcomes. Child Welfare 2010; 89(2): 21–38.

Podmostko, M. Tunnels and Cliffs: A Guide for Workforce Development Practitioners and Policymakers Serving Youth with Mental Health Needs. Washington, DC: National Collaborative on Workforce and Disability for Youth, Institute for Educational Leadership, 2007.

Herz D, Lee P, Lutz L. Addressing the Needs of Multi-System Youth: Strengthening the Connection Between Child Welfare and Juvenile Justice. Center for Juvenile Justice Reform, Robert F. Kennedy Children’s Action Corps, 2013.

Luecking DM, Luecking RG. Translating research into a seamless transition model. Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals 2013. doi:10.1177/2165143413508978.

Koball H, et al. Synthesis of Research and Resources to Support At-Risk Youth, OPRE Report # OPRE 2011-22. Washington DC; Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, US Department of Health and Human Services, 2011.

Marsenich, L. A Roadmap to Mental Health Services for Transition Age Young Women: A Research Review. Sacramento, CA: California Institute for Mental Health, 2005.

Test DW, Fowler CH, Richter SM, et al. Evidence-based practices in secondary transition. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals 2009; 32: 115-128.

Test DW, Mazzotti VL, Mustian AL, et al. Evidence-based secondary transition predictors for improving postschool outcomes for students with disabilities. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals 2009, 32: 160-181.

Schwartz, AA, Jacobson JW, Holburn SC. Defining person-centeredness: Result of two consensus methods. Education and Training in Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities 2000; 35: 235–249.

Taylor JE, Taylor JA. Person-centered planning: evidence-based practice, challenges, and potential for the 21st century. Journal of Social Work in Disability & Rehabilitation 2013; 12(3): 213–35.

Dresser K, Clark HB, Deschênes N. Implementation of a positive development, evidence-supported practice for emerging adults with serious mental health conditions: The Transition to Independence Process (TIP) Model. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research 2015; 42(2).

Woolsey L, Katz-Leavy J. Transitioning Youth with Mental Health Needs to Meaningful Employment and Independent Living. Washington, DC: National Collaborative on Workforce and Disability for Youth, Institute for Educational Leadership; 2008.

Walker JS, Flower KM. Provider perspectives on principle-adherent practice in empirically-supported interventions for emerging adults with serious mental health conditions. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research 2015; 42(2).

Fraker T, Rangarajan A. The social security administration’s youth transition demonstration projects. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 2009; 30: 223–240.

US Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Cooperative Agreements for State/Community Partnerships to Integrate Services and Supports for Youth and Young Adults 16-25 with Serious Mental Health Conditions and Their Families: Request for Applications. Available online at http://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/DownloadDocument?documentID=340451&version=0. Accessed January 10, 2015.

Walters D, Zanghi M, Ansell D, et al. Transition Planning with Adolescents: A Review of Principles and Practices Across Systems. Tulsa, OK: National Resource Center for Youth Development, 2010.

Gullan RL, Power TJ, Leff SS. The role of empowerment in a school-based community service program with inner-city, minority youth. Journal of Adolescent Research 2013; 28(6): 664–689.

Brink AJW, Wissing MP. Review article: A model for a positive youth development intervention. Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health 2012; 24(1): 1–13.

Morton MH, Montgomery P. Youth empowerment programs for improving adolescents’ self-efficacy and self-esteem: A systematic review. Research on Social Work Practice 2012; 23(1): 22–33.

Fixsen D, Naoom SF, Blase KA, et al. Implementation Research: A Synthesis of the Literature. Tampa, FL: University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, The National Implementation Research Network, 2005.

Steckler A, Linnan LE (Eds). Process Evaluation for Public Health Interventions and Research. San Francisco: Jossey‐Bass, 2002.

Frechtling JA. Logic Modeling Methods in Program Evaluation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2007.

Rogers PJ, Petrosino A, Huebner TA, et al. Program theory evaluation: Practice, promise, and problems. New Directions for Evaluation 2000; 87: 5-13.

Savaya R, Waysman M. The logic model: A tool for incorporating theory in development and evaluation of programs. Administration in Social Work 2005; 29(2): 85-104.

Hamilton JD, Kendall PC, Gosch E, et al. Flexibility Within Fidelity. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2008; 47(9): 987–993.

Barth RP, Lee BR, Lindsey MA, et al. Evidence-based practice at a crossroads: The timely emergence of common elements and common factors. Research on Social Work Practice 2011; 22(1): 108–119.

Duncan BL, Miller SD, Wampold BE, et al. (Eds). The Heart and Soul of Change: Delivering What Works, Second Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2010.

Chorpita BF, Daleidan EL. Mapping evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: Application of the distillation and matching model to 615 treatments from 322 randomized trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 2009; 77(3): 566-579. doi: 10.1037/a0014565.

Garland AF, Bickman L, Chorpita BF. Change what? Identifying quality improvement targets by investigating usual mental health care. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 2010; 37(1): 15-26.

Bruns EJ, Walker JS, Bernstein AD, et al. Family voice with informed choice: Coordinating wraparound with research-based treatment for children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology 2014; 43(2): 256-269.

Walker JS, Gowen K, Jivanjee P, et al. Pathways to Positive Futures: State-of-the-Science Conference Proceedings (Part 1). Portland, OR: Portland State University, Research and Training Center for Pathways to Positive Futures, 2013.

Masten AS, Coatsworth JD, Neemann J, et al. The structure and coherence of competence from childhood through adolescence. Child Development 1995; 66: 1635–1659.

Masten AS, Burt KB, Roisman GI, et al. Resources and resilience in the transition to adulthood: Continuity and change. Development and Psychopathology 2004; 16: 1071–1094.

Lerner RM, Freund AM, De Stefanis I, et al. Understanding developmental regulation in adolescence: The use of the selection, optimization, and compensation model. Human Development 2001; 44: 29–50.

Skaletz C, Seiffge-Krenke I. Models of developmental regulation in emerging adulthood and links to symptomatology. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development 2010; 130: 71–82.

Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Guthrie IK, et al. Age changes in prosocial responding and moral reasoning in adolescence and early adulthood. Journal of Research on Adolescence 2005; 15: 235–260.

Hawkins MT, Letcher P, Sanson A, et al. Positive development in emerging adulthood. Australian Journal of Psychology 2009; 61(2): 89–99.

Salmela-Aro K. Personal goals and well-being: How do young people navigate their lives? New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development 2010; 130: 13-26.

Schmid KL, Phelps E, Lerner RM. Constructing positive futures: Modeling the relationship between adolescents’ hopeful future expectations and intentional self regulation in predicting positive youth development. Journal of adolescence 2011; 34(6): 1127–1135.

Li J, Julian MM. Developmental relationships as the active ingredient: A unifying working hypothesis of “what works” across intervention settings. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 2012; 82(2): 157–166.

Kia-Keating M, Dowdy E, Morgan ML, et al. Protecting and promoting: An integrative conceptual model for healthy development of adolescents. The Journal of Adolescent Health 2011; 48(3): 220–228.

Lerner RM. Theories of human development: Contemporary perspectives. In: W Damon, RM Lerner (Eds). Handbook of Child Psychology, Volume 1: Theoretical Models of Human Development, Fifth Edition. New York: Wiley, 1998, pp. 1–24.

Amerikaner MJ. Continuing theoretical convergence: A general systems theory perspective on personal growth and development. Journal of Individual Psychology 1981; 37: 31–53.

Bronfenbrenner U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980.

Bronfenbrenner U, Morris PA. The ecology of developmental processes. In: W Damon, RM Lerner (Eds). Handbook of Child Psychology, Volume 1: Theoretical Models of Human Development, Fifth Edition. New York: Wiley, 1998, pp. 993–1027.

Shapiro SL, Schwartz GE. The role of intention in self-regulation: Toward intentional systemic mindfulness. In: M Boekaerts, PR Pintrich, M Zeidner (Eds). Handbook of Self-Regulation. San Diego: Academic Press, 2005, pp. 253–273