Abstract

During collaborative learning, computer-supported or otherwise, students balance task-oriented goals with the interpersonal goals of relationship-building. This means that in peer tutoring, some pedagogically beneficial behaviors may be avoided by peer tutors due to their likelihood to get in the way of relationship-building. In this paper, we explore how the interpersonal closeness between students in a peer tutoring dyad and the peer tutors’ instructional self-efficacy impacts those tutors’ delivery style of various tutoring moves, and explore the impact those tutoring move delivery styles have on their partners’ learning. We found that tutors with lower social closeness with their tutees provide more positive feedback to their tutee and use more indirect instructions and comprehension-monitoring, but this is only the case for tutors with greater tutoring self-efficacy. And in fact, those tutees solved more problems and learned more when their tutors hedged instructions and comprehension-monitoring, respectively. We found no effect of hedging for dyads with greater social closeness, on the other hand, suggesting that interpersonal closeness may reduce the face-threat of direct instructions and comprehension-monitoring, and hence reduce the need for indirectness, while tutors’ instructional self-efficacy allows tutors to use those moves without feeling threatened themselves. These results emphasize that designers of CSCL systems should understand the nature of how the interpersonal closeness between collaborating students intersects with those students’ self-efficacy to impact the use and delivery of their learning behaviors, in order to best support them in collaborating effectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In collaborative learning interactions, whether computer-mediated or face-to-face, students balance task-oriented goals with the interpersonal goals of relationship-building (Tracy and Coupland, 1990). In some forms of collaborative learning, such as peer tutoring, students may offer each other advice, instructions, or feedback. Such pedagogical behaviors, while supporting the task goal of helping their partner learn, may also conflict with the interpersonal goal of relationship-building. That conflict may arise from the potential for such behaviors to be pedagogically helpful, while at the same time, potentially threatening for their partner’s “positive face”, or desire to be approved of by others (Brown and Levinson 1987).

To mitigate the relational consequences of pedagogical behaviors that are likely to threaten tutees’ interpersonal needs, such as feedback and comprehension-monitoring, peer tutors without sufficient interpersonal closeness with their tutee might avoid providing the necessary tutoring move altogether (Person et al. 1995). If, however, they are more skilled at attending to interpersonal needs, they might phrase their words in an indirect, or “hedged”, manner, reducing the implicit threat to their partners’ “face”. Some computer supports for learning, such as some forms of intelligent tutoring systems (ITS), indiscriminately apply this indirect style to the feedback and instructions provided to students, to reduce the threat of feedback and instructional directives (Johnson and Rizzo 2004). An overuse of such indirect instructional moves, however, may have a negative impact on student learning, due to the inherent ambiguity of indirectness (Person et al. 1995).

Therefore, if computer-supported collaborative learning (CSCL) systems were to simply prompt all collaborating students to always use indirectness, as in the ITS example, such a recommendation may not be the most effective or socially-appropriate way for peer tutors to deliver feedback or instructions. As Carmien et al. (2007) argue, students bring their own internal scripts to bear in collaborative learning interactions, which may conflict with the scripts provided by a CSCL system. In order to design CSCL systems that can support students’ productive collaborative discourse (as in Tegos et al. 2016), we must first understand whether and how students’ interpersonal closeness impacts with the resources they bring to bear (here, tutoring self-efficacy and prior knowledge) to impact their use and delivery style of various tutoring strategies. Will effective tutoring moves be avoided due to concerns about their potential face-threat? Will peer tutors modify the delivery style of such moves to mitigate that potential face-threat?

In this paper, we first investigate how peer tutors’ interpersonal closeness with their tutees impacts their use and delivery style of potentially face-threatening tutoring moves like (1) instructional directives, (2) feedback, and (3) explicit reflections on their partners’ comprehension. We include in this analysis two potentially mediating factors: tutors’ prior domain knowledge and their tutoring self-efficacy (the belief that one is a capable tutor), We then investigate the relationship between peer tutors’ delivery style, their domain knowledge and tutoring self-efficacy, and their interpersonal closeness with their tutee, on tutees’ problem-solving and learning.

Results support the importance of a process-oriented approach to understanding the delivery style of tutoring behaviors, and the importance of bringing factors other than simply friendship to bear in studying the impact of social influences on learning. We find that while peer tutors with a less strong relationship with their tutee can support their partners’ learning behaviors, problem-solving, and learning gains by hedging some of the more face-threatening tutoring moves, not all peer tutors are equally as likely to hedge such moves. We find that peer tutors with greater self-efficacy for their ability to tutor are in fact more likely to hedge their face-threatening tutoring moves, suggesting that a greater tutoring self-efficacy might allow peer tutors to hedge, potentially appearing to be uncertain, in order to save their partners’ face when needed. These findings can help inform the design of CSCL systems that might detect students’ interpersonal closeness or tutoring self-efficacy and suggest different ways for students to deliver instructions, feedback, and comprehension-monitoring to mitigate face-threat, or lead to a system with virtual agents that could intervene to provide that support itself when necessary.

Related work

Reciprocal peer tutoring is a form of collaborative learning where same-age students work together by taking turns teaching one another, despite neither of them being an expert (Palinscar and Brown 1984). Prior work has shown that it can be an improvement over individuals learning alone, but the differences between novice peer tutors and expert tutors in both content knowledge and pedagogical knowledge may have significant consequences for both the process and outcomes of tutoring (Palinscar and Brown 1984). To better understand whether and how interpersonal closeness between peer tutors and their tutees intersects with tutors’ domain knowledge and tutoring self-efficacy to impact their use of indirectness while tutoring, we draw on a number of prior theories. First, we describe the role that “face”, or, desire to be approved of by others (Goffman 2016; Brown and Levinson 1987) may play in the tutoring process, for both tutor and tutee. We then discuss prior approaches to face-threat mitigation in learning, such as through indirectness in tutoring. We then discuss other potential interpersonal goals that tutors’ indirectness might serve instead of face-threat mitigation, such as to demonstrate tutors’ own uncertainty or lack of confidence in their own ability to tutor. Finally, we discuss the nature of interpersonal closeness and how the relationship or rapport between tutor and tutee might impact the ways that tutors pursue the interpersonal goal of face-threat mitigation.

Impact of face-threat in peer tutoring

First, prior work has argued that the provision of instructional feedback, directions, or unsolicited advice is a socially mediated process impacted, in part, by the interpersonal closeness between tutor and tutee (Wichmann and Rummel 2013; Feng and Magen 2015). The experience of being tutored by a peer may be a highly threatening experience for tutees, and as such, effective tutoring moves may be avoided by peer tutors when their interpersonal goals of building a relationship with their partner conflict with the interactional goals of tutoring (Person et al. 1995).

To understand the impact of those potentially threatening pedagogical moves on peer tutoring, in particular the delivery of feedback, instructions, and tutors’ explicit reflections on their partners’ comprehension, we draw on theories of face management and politeness (Goffman 2016; Brown and Levinson 1987). According to Brown and Levinson, social actors are motivated by their desire for what is referred to as positive face, or the desire to be approved of by others, and negative face, which is the desire to be autonomous and unimpeded by others (Brown and Levinson 1987). According to Goffman, interlocutors (more so in some cultures, but to some extent in all cultures) are careful to avoid threatening their conversational partners’ face – by approving of the partner to uphold positive face, and by allowing the partner more autonomy, to protect the partner’s negative face. If face threat is unavoidable, such as when a tutor must correct a tutee’s answer, Brown and Levinson claims that the speaker will attempt to mitigate the threat by speaking indirectly or obliquely, by being polite, or by simply avoiding the provision of that type of response entirely.

Tutors’ instructions or directions, if they take the form of demands, may thus threaten students’ negative face, and tutors’ instructional feedback and comprehension-monitoring, if given in a blunt manner, may threaten their tutees’ positive face (Brown and Levinson 1987; Johnson and Rizzo 2004; Roscoe and Chi 2008). Prior work has argued that, in response to such face-threat, untrained peer tutors use fewer instances of comprehension monitoring in part due to the social pressure to avoid what might be seen as a threatening comparison between tutor and tutee (Ray et al., 2013). Thus, peer tutors’ desire to communicate agreeable, face-boosting information may distort or impinge on the quality of the collaborative learning between a peer tutor and tutee (Dame and Tynan 2005; Person et al. 1995).

Mitigating face-threat in learning

More skilled peer tutors, however, may be able to mitigate the face threat of such instructional moves to their students, perhaps by delivering those moves in an indirect or polite way (Person et al. 1995). As we described above, indirectness is one of the verbal conversational strategies that play a role in face management (some others are praise and acknowledgement). However, as Person et al. (1995) have argued, while indirectness and politeness may reduce face-threat, they may also introduce ambiguity and vagueness when used in an instructional or tutoring context (Person et al. 1995). Particularly for what Person et al. (1995) refer to as “closed-world” domains, such as in algebra, where there is a definitive answer to problems, the repeated use of indirectness over time from the tutor may lead the tutees to distrust the tutors’ competence.

In a computer-supported collaborative learning (CSCL) context, the medium of the interaction is likely to impact the ways in which collaborating students attempt to mitigate the face-threat of their instructional moves. For instance, Mottet and Beebe (2002), Kerssen-Griep et al. (2008) and many others have identified a set of nonverbal behaviors that can help mitigate face-threat in classroom instruction. They identified that interpersonally skilled instructors use the nonverbal immediacy behaviors of establishing eye contact, smiling, and body orientation to indicate their connection to the students as a way of reducing potential face-threat (Mottet and Beebe 2002; Kerssen-Griep et al. 2008). For CSCL systems, however, the medium of interaction may not allow for such nonverbal behaviors. If the CSCL system is purely text-based, then the students no longer have the ability to use nonverbal immediacy to mitigate face-threat, and must instead rely on verbal strategies such as indirectness or avoiding the potentially threatening move entirely (Morand and Ocker 2003).

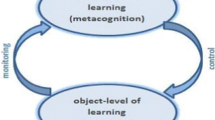

Impact of domain knowledge and instructional self-efficacy on indirectness

While face-threat mitigation may be one role played by indirectness in instructional moves from peer tutors, it may instead be the case that hedging is used an indicator of the uncertainty of the peer tutor. Coates (1987) has argued that hedging is used as part of socio-cognitive processes to fulfill the conversational strategies of politeness, uncertainty, or indirectness (Coates 1987). Hedges, and other markers of indirectness such as “subjectivizers” like “I think” or “I guess”, can thus be viewed as what Prince et al. (1982) calls “shields”, to create a distance between the speaker and their proposition (Prince et al. 1982). Rowland (2007), in his analysis of indirectness in the math classroom, describes the linguistic role that hedging plays in middle school students’ verbalization of mathematic predictions (Rowland 2007). According to Rowland, students use hedges, subjectivizers, and what he refers to as “approximators” or “vague category extenders” (“and stuff”, “or something”, etc) for much the same shielding function, using uncertainty to save them from the risk of embarrassment if they are wrong in their predictions of the answer (Rowland 2007). However, it is not clear whether and in what situations peer tutors use indirectness to indicate their own uncertainty and save their own face, or to allow for the possibility of being wrong in order to save their tutees’ face.

Although expert tutors and teachers may be able to effectively mitigate the face-threat of a tutoring move through the strategic use of indirectness, politeness, or a self-effacing disclosure, untrained peer tutors may not be as deft in their face-work (Kerssen-Griep et al. 2008). Prior work has shown that in addition to domain knowledge, teachers’ instructional self-efficacy is likely to impact their ability to attend to the interpersonal goals of teaching as well as the instructional goals (Gibson and Dembo 1984; Mojavezi and Tamiz 2012; Saklofske et al. 1988). Teachers’ instructional self-efficacy, or their beliefs about their ability to impact student outcomes and the confidence that they can do so, have been shown to impact teachers’ use of different types of feedback (Gibson and Dembo 1984) as well as impacting their students’ motivation and achievement (Mojavezi and Tamiz 2012). In addition, though we did not measure tutoring ability, we used the tutors’ score on a pre-test as a proxy for their prior domain knowledge, following Rowan et al.’s (1997) findings that teacher prior domain knowledge was predictive of their students’ performance, and following the intuition that tutors’ prior domain knowledge may impact their own certainty in their responses. However, those prior findings have been for adult teachers, and thus it is not clear whether and how instructional self-efficacy impacts peer tutors’ ability to balance between the interpersonal and instructional goals of tutoring. That prior work also does not take into account the interpersonal closeness of the tutor and the tutee, and is thus unable to identify whether or how that closeness impacts the tutors’ use of face-threat mitigation in tutoring.

Impact of interpersonal closeness on face-threat mitigation

In some cases, it is possible that the potential face-threat of the three types of tutoring moves described above (feedback, instructions, and comprehension monitoring) may not need to be explicitly mitigated by a peer tutor at all. Instead of delivering potentially face-threatening moves indirectly, the interpersonal closeness between students may allow for behaviors that might otherwise be perceived as face-threatening to instead be permissible (Brown and Levinson 1987). This follows theories of rapport-building, such as from Spencer-Oatey (2005), which suggest that a greater rapport, or interpersonal closeness, between interlocutors allows for speech acts which would otherwise be perceived as face-threatening.

To operationalize the development of interpersonal closeness and its impact on face-management, we draw on Tickle-Degnen and Rosenthal (1990)’s work on interpersonal rapport as well as Spencer-Oatey’s (2005) model of face-management, as integrated into a theory of rapport-building that incorporates face-management, mutual attentiveness, and coordination between members of an interacting dyad, by Zhao et al. (2014). As rapport, or short-term interpersonal closeness, begins to develop, partners convey their mutual attention to each other, both nonverbally, as well as through verbal behaviors that index that attention, such as referencing shared interests and experiences (Zhao et al. 2014). Initially, partners may need to expend more effort in managing the face-threat to their partner, perhaps through what Tickle-Degnen and Rosenthal (1990) have described as nonverbally displaying positivity to the other person. This may also take the form of face-boosting behaviors like praise or self-effacing negative self-disclosure, such as “I suck at these kinds of problems too” (Zhao et al. 2014). These theories argue that we would expect the relative importance of face management to decrease as the relationship or rapport between tutor and tutee develops (Spencer-Oatey 2005; Tickle-Degnen and Rosenthal 1990).

In tutoring, prior work has found, using friendship as a proxy for long-term rapport, that tutoring dyads of friends engage in more violations of social norms, such as playful teasing and social challenges, and that these are correlated with learning gains in friends. Those same behaviors, however, led to decreased learning among strangers (Ogan et al. 2012). This further suggests that a social relationship between tutor and tutee allows them to playfully challenge the other while tutoring, in what might be seen as face-threatening acts if done between strangers. However, this prior work did not look at the impact of such social relationships (friendship or rapport) on indirect delivery of tutoring moves as one way to mitigate the potential face-threat involved in learning, and how tutors’ self-efficacy predicted their use of this indirectness, as described above.

In sum, while some have argued that indirectness may be used by peer tutors to mitigate potential face-threat to tutees, others have argued that indirectness is instead used as a shield to save the speaker’s face when they are uncertain. In addition, some prior work has argued that indirectness is beneficial for mitigating face-threat to students, while others have argued that it might be harmful due to its ambiguity, or that it may be simply unnecessary for dyads of students with sufficient interpersonal closeness. However, it remains unclear (1) whether and to what extent untrained peer tutors’ indirectness is used to soften the blow of potentially face-threatening tutoring moves or to indicate their own uncertainty; (2) how that use of indirectness is impacted by their interpersonal closeness with their tutee, their instructional self-efficacy, and domain knowledge; and (3) how that indirectness impacts their tutees’ subsequent problem-solving and learning gains. To help address this gap, we propose the following research questions.

Research questions

RQ1

How does a tutoring dyad’s interpersonal closeness impact tutors’ use of potentially face-threatening tutoring moves?

RQ2

How do tutors’ self-efficacy and interpersonal closeness impact their use of indirectness while delivering those tutoring moves?

RQ3

How does a tutor’s use of indirect feedback, instructions, and comprehension-monitoring impact tutees’ learning behaviors and outcomes?

Methods

We seek to investigate how the interpersonal closeness between peer tutors and their tutees impacts the tutors’ use of indirectness with instructions, feedback, and comprehension monitoring, and how those moves in turn impact tutees’ learning. We will first describe the peer tutoring data we collected, including the two ways we operationalize the interpersonal closeness between members of a peer tutoring dyad (i.e. their relationship and their rapport). We then describe the set of tutoring moves and indirectness dialogue markers that we annotated our dialogue corpus for, and, finally, we describe the measures we use to operationalize tutors’ self-efficacy and tutees’ learning.

Dialogue corpus

The dialogue corpus described here was collected as part of a larger study on the effects of rapport-building on reciprocal peer tutoring. The participants were assigned to 12 dyads that alternated tutoring one another in linear algebra equation solving for 5 weekly hour-long sessions, for a total corpus of ~60 h of face-to-face interactions. Each session was structured such that the students engaged in brief social chitchat in the beginning, then had one tutoring period of 20 min with one of the students randomly assigned to the role of tutor. They then engaged in another social period, and concluded with a second tutoring period where the other student was assigned the role of tutor. This process was repeated for five sessions over five weeks. As each student was randomly assigned to be the tutor for half of the tutoring periods, they were not expected to have any greater prior knowledge than their partner for the problems they were tutoring them on.

All students were supported with a set of instructions on how to teach the particular problems for which they were assigned the role of tutor. These instructions include procedural instructions for problems of a similar form as the ones the tutees were solving. The students took a pre-test before the first session and a post-test after the fifth session to assess their learning gains. The participants (mean age = 13.5, min = 12, max = 15) came to a lab on an American university campus in a mid-sized city for the study. Half were male and half were female, assigned to same-gender dyads, so that, in other work with this corpus, gender differences in the social, rapport-building behaviors of the participants could be identified. No gender differences were found here. To investigate how the use of various tutoring behaviors differs between dyads with varying degrees of interpersonal closeness, we used friendship as a proxy for long-term closeness and asked half of the participants to bring a same-age, same-gender friend to the session with them, and for the other half of the dyads, we paired them with a stranger. Audio and video data were recorded, transcribed, and segmented for clause-level dialogue annotation, following Chi (1997).

Rapport rating

The rapport, or short-term interpersonal closeness between the participants, was evaluated using a “thin-slice” approach following Ambady and Rosenthal (1992). They found that rapidly-made judgments of interpersonal interactions were highly accurate assessments of those interpersonal dynamics (Ambady and Rosenthal 1992). Following this, we divided our corpus into 30-s video slices, and provided naive raters with a simple definition of rapport, as well as provided them with those clips in a randomized order, so they would rate each slice’s rapport, and not the delta across multiple slices. Because, in the thin-slice methodology, the raters are intended to be naïve observers, we did not use a train-retrain approach as is common in dialogue annotations (Chi 1997; Ambady and Rosenthal 1992).

Instead, three raters rated the rapport present in each slice in our corpus on a Likert scale from 1 to 7, so that those ratings could provide ground truth for future analyses of the rapport dynamics. To account for each rater’s overuse or underuse of the Likert scale categories, we used a weighted majority vote approach, following Sinha and Cassell (2015), and Kruger et al. (2014). We weighted each rater’s vote for the slice’s rating by the inverse of that rater’s frequency of use for that rating category, so that each rater’s vote was weighted to account for their overall overuse or underuse of a particular rating. The final single rating was then chosen for each slice using that inverse bias-corrected weighted majority vote approach.

While this is useful for obtaining the rapport between participants at any given moment of the interaction, it does not provide a summary measure with which we can understand the relationship between the interpersonal closeness of the dyad, the tutors’ use of indirectness with their tutoring, and the tutees’ learning. Therefore, from the roughly 120 thirty-second slices in each hour-long session, we calculated a summary rapport score for each session following Sinha (2016). Prior work has shown that statistical summaries such as a measure of central tendency or proportion of high and low ratings of rapport collapse the temporal dimension and are not as robust as more stochastic-based models which capture the evolution of rapport over time (Sinha 2016). Sinha (2016) found a significant relationship between a stochastic-based measure of rapport and students’ learning. This was more predictive of student learning than statistical summaries such as the simple average, and thus, we adopt Sinha’s approach for generating one such stochastic measure of rapport, or “utopy”. The “utopy” is, intuitively, the likelihood of the rapport to be increasing, weighted by the size of the increase; this measure can thus capture the temporal dynamics of interpersonal closeness development.

To obtain this measure for each session, we fit a Markov chain of order 1 to the sequence of 120 rapport ratings in each session, to generate the transition probability matrix for the likelihood of that dyad to transition from one rapport level to another. We then compute the “utopy” by summing the transition probabilities of each transition from one rapport level to another (e.g. rapport 2 to 4), weighting each of the transition probabilities by their distance from the diagonal, so that larger changes in rapport were given more weight. This provides us with a measure of the “utopy” for a given session, or the likelihood that rapport will be transitioning to higher states for that dyad in that particular session (Dillenbourg 2015; Sinha 2016). In other work, we have found a significant association between utopy and students’ problem-solving and learning gains (reference removed). In this paper, we build off of that work by using the utopy measure to investigate the relationship of rapport dynamics with learning process behaviors, here, indirectness with peer tutoring moves.

Dialogue annotation

As part of a larger study on the relationship between rapport-building and peer tutoring, this corpus was annotated by a set of four trained annotators for a set of pedagogical, tutoring-related behaviors from both the tutor and tutee, as well as a set of social, rapport-building verbal conversational strategies and nonverbal behaviors (not discussed in this article). In Table 1, we describe the tutoring strategies included in the analyses in this paper. This set of tutoring behaviors includes feedback from tutors on their partner’s correctness, step-level procedural instructions (also called “knowledge-telling”), and explicit comprehension monitoring on the part of the tutor (following Madaio et al. 2016). We also annotated for learners’ step-level verbalizations of their problem-solving procedures, to understand how their self-explanations were impacted by their partners’ tutoring strategies. The Krippendorff’s alpha for all codes was over 0.7.

To understand the ways that tutors in dyads with differing levels of interpersonal closeness (both friendship status and rapport) modified the delivery style of their tutoring instructions and feedback, we coded our corpus for four types of indirectness. These indirectness markers were coded independently of the tutoring moves. Thus the indirectness markers may have been either used alone or co-occurring with the tutoring moves (e.g. instructions, advice, or feedback). We annotated for: apologizing, hedging or qualifying, the use of vague category extenders, and “subjectivizing” (Zhang 2013; Neary-Sundquist 2013; Fraser 2010), as described in more detail in Table 1. The Krippendorff’s alpha for all four codes was over 0.7.

To understand how tutoring moves were delivered indirectly, we analyzed the co-occurrence of the annotated indirectness markers with the annotated tutoring strategies for each given clause. We identified clauses as indirect feedback if a clause had an annotation for indirectness and an annotation for feedback, either positive or negative. Typical examples of indirect feedback include: “I think you got it.” “I guess that’s what it is.” “Oh, no, actually, it’s not.” “No, it’s just nineteen.” We similarly identified each clause as indirect instructions if it had an annotation for indirectness and an annotation for procedural instructions. Typical examples of indirect instructions are: “Actually, just add five here.” “I think you’re gonna divide it by a fraction or something.” “I would probably subtract the sixteen.” Finally, we labeled each clause as indirect comprehension-monitoring if it had an annotation for indirectness and an annotation for comprehension monitoring. Some typical examples include: “Yeah, you just got mixed up between the terms.” “It just seems like you roam a lot.” “Oh, I guess you’re not confused.” All other instances of these three tutoring strategies without co-occurrence with an indirectness marker were thus identified as “direct” feedback, instructions, or comprehension-monitoring.

Finally, we provided the participants with a questionnaire following the study with a set of items for constructs relevant to rapport-building and the tutoring process. To evaluate their self-efficacy for tutoring, we used a 7-item scale indexing whether the participants believed that they were able to be effective in positively impacting their tutees, following Gibson and Dembo’s construct of “personal teaching efficacy” (Gibson and Dembo 1984). We use a median-split on those survey results to categorize tutors as high or low self-efficacy, relative to the rest of the participants.

Results

In the following sections, we investigate our research questions about the impact that interpersonal closeness and tutors’ prior knowledge and tutoring self-efficacy have on peer tutors’ tutoring strategies. We do this first by analyzing the base rates of three types of tutoring behaviors and the impact of the aforementioned factors on tutors’ use of those behaviors. We then describe tutors’ base rates of indirectness markers (qualifiers, subjectivizers, etc) and investigate the impact that interpersonal closeness, tutors’ prior knowledge and tutoring self-efficacy have on tutors’ co-occurring usage of indirectness with the three tutoring moves, or, their indirect tutoring strategies. Finally, we investigate the impact that these indirect tutoring strategies, and their direct counterparts have on tutees’ responses and learning outcomes. For the following analyses, all results are significant after correcting for multiple hypothesis testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg post-hoc correction (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995).

Peer tutors’ use of face-threatening tutoring moves

First, we investigated our research question about whether tutors with lower interpersonal closeness with their tutees used fewer instances of negative feedback and comprehension monitoring (RQ1). Due to the potential for those two types of tutoring moves in peer tutoring dyads with lower interpersonal closeness to be perceived as face-threatening, we hypothesized that tutors in dyads of strangers and tutors in low-rapport dyads would provide fewer instances of negative feedback (Person et al. 1995) and fewer instances of explicit comprehension monitoring (Roscoe and Chi 2008). Conversely, we hypothesized that friends and high-rapport dyads, who may have less need for face-threat mitigation (Spencer-Oatey 2005), would thus provide negative feedback more often (Person et al. 1995), as well as providing more comprehension monitoring (Roscoe and Chi 2008). In this section, we analyze all occurrences of those two types of tutoring moves (feedback and comprehension monitoring), regardless of whether they were delivered in a direct or indirect manner. We normalized the aggregate frequencies for those two tutoring moves by the total number of “on-task” utterances, or the total number of annotated tutoring strategies (e.g. explanations, feedback, comprehension monitoring) given by each speaker, in each session, following Madaio et al. (2016).

To investigate this hypothesis about the influence of interpersonal closeness and self-efficacy on tutoring strategies, we first ran an omnibus repeated measures MANOVA on the normalized frequency of tutors’ negative feedback, positive feedback, and comprehension-monitoring. We crossed the between-subjects factors of relationship (friend/stranger), rapport (high/low), prior knowledge, and tutoring self-efficacy with the within-subject factor of session and tutoring period, using each dyad’s tutoring period and session number as error terms. The rapport and relationship factors are intended to capture the phenomena of interpersonal closeness in the short-term and long-term, respectively. In this dataset there was no correlation between the rapport and the relationship (i.e. there are both high- and low-rapport dyads of friends and strangers), and so we include both factors in our model. This MANOVA revealed a significant multivariate main effect of relationship (F (3, 68) = 5.23, p < 0.01) on the three outcome variables (negative feedback, positive feedback, comprehension-monitoring). Given the significance of the overall omnibus test, univariate tests were conducted to identify the differential impact of those effects on the three outcome variables.

Surprisingly, for the univariate model for negative feedback, there was no statistically significant effect of any of the factors. For the univariate model for positive feedback, however, we found a highly significant univariate main effect of relationship on the amount that tutors used positive feedback (F(1,64) = 12.8, p < .001). To find the direction of that difference, we ran a t-test, and found that stranger tutors were significantly more likely (t(71) = 3.77, p < .001) to use positive feedback (m = .17, sd = .12) than friend tutors (m = .08, sd = .08). We hypothesized that perhaps stranger tutors were using more positive feedback because their tutees were solving more problems correctly. Therefore, we conducted a t-test, which showed that stranger tutees did not solve significantly more problems than friend tutees. This suggests that this positive feedback was serving an interpersonal function, rather than the interactional function of indicating correctness. Finally, for the univariate model for comprehension-monitoring, we found a significant univariate main effect of relationship on the amount that tutors provide comprehension monitoring (F(1,70) = 5.9, p < .05). Friend tutors used significantly more (m = 0.05, sd = 0.04) comprehension monitoring than stranger tutors (m = 0.03, sd = 0.02), at (t(60.9) = 2.43, p = .01), confirming our hypothesis.

Peer tutors’ overall use of indirectness

Before we investigated our research questions about the co-occurrence of indirectness markers with tutoring strategies, we first inspected the base rate of the four types of indirectness we annotated, used in any utterance in our corpus (both on-task and off-task). Because our annotators coded indirectness in any utterance in the corpus, we normalized the frequency of these codes by the total number of utterances from that speaker, in that session. By far the most frequently used marker of indirectness in our dataset was the use of qualifiers or hedges (e.g. “just”, “actually”, etc.) with normalized mean = .05 and standard deviation = .04, followed by subjectivizers (e.g. “I think”, “I guess”, etc) (m = .02, sd = .03), and apologies (m = .01, sd = .01), and with vague category extenders by far the most infrequent (e.g. “and stuff”, “or something”, etc.) (m = .002, sd = .01). This distribution aligns with findings from Rowland’s (2007) work studying the use of hedges, subjectivizers (what he calls “shields”), and extenders in student-teacher mathematics lessons. See Fig. 1 for a boxplot showing the distribution of the frequency of each of the four types of indirectness annotated for, as normalized by the total number of utterances from that speaker, in that session.

Peer tutors’ use of indirectness with tutoring moves

We then wanted to investigate the factors impacting peer tutors’ use of each of these four types of indirectness when used with their procedural instructions, feedback, and comprehension monitoring (RQ2). From prior literature on the use of hedges and subjectivizers to convey uncertainty (Rowland 2007), we hypothesized that tutors with lower tutoring self-efficacy would use more indirect language to indicate their uncertainty. However, an alternative hypothesis is that tutors with greater tutoring self-efficacy would attend more to their tutees’ needs for face-management and would thus use more indirect language to mitigate the potential face-threat of tutoring moves (Brown and Levinson 1987; Kerssen-Griep et al. 2008; Saklofske et al. 1988). We additionally hypothesized that tutors with low interpersonal closeness with their tutees (stranger tutors and tutors in low-rapport dyads), would use a more indirect style when delivering tutoring moves that may be potentially face-threatening (feedback, procedural instructions, and comprehension-monitoring) than tutors with greater interpersonal closeness (Brown and Levinson 1987; Johnson and Rizzo 2004).

To investigate this hypothesis, we first ran an omnibus repeated measures MANOVA on the normalized frequency of tutors’ indirect feedback, indirect instructions, and indirect comprehension-monitoring. To do this, we first computed the aggregated frequency of the three annotated tutoring moves that co-occurred with an annotation of an indirectness marker in the same utterance, as described in the methods section. We then normalized each of these aggregated frequencies by the total number of occurrences of that tutoring move by that speaker, in that session, to control for the opportunities for a given tutoring move to be delivered indirectly. As in RQ1, we crossed the between-subjects factors of relationship (friend/stranger), rapport (high/low), prior knowledge, and tutoring self-efficacy with the within-subject factor of session and tutoring period, using each dyad’s tutoring period and session number as error terms. This MANOVA revealed a significant multivariate interaction effect of relationship with tutoring self-efficacy (F (3, 33) = 3.00, p < 0.05) on the three outcome variables (indirect feedback, indirect instructions, and indirect comprehension-monitoring). Given the significance of the overall omnibus test, univariate tests were conducted to identify the differential impact of those effects on the three outcome variables. For the univariate model for indirect feedback, there was no statistically significant effect of any of the factors.

For the univariate model for tutors’ use of indirect instructions, we found a highly significant main effect of relationship (F(1,70) = 7.4, p < .01). To find the direction of that difference, we ran a Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test, for comparing means of non-normal distributions. Tutors who paired with a stranger were significantly more likely (U = 3749, p < .05) to use indirect instructions (m = .02, sd = .03) than tutors paired with a friend (m = .01, sd = .02), which aligns with our hypothesis about interpersonal closeness. In this univariate model, there was also a significant interaction effect of rapport and self-efficacy on tutors’ use of indirect instructions (F(1,70) = 4.5, p < .05), regardless of the relationship with the tutee. High-self-efficacy tutors with low rapport with their tutees were significantly more likely (U = 4052, p < .001) to use more indirect instructions (m = .03, sd = .02) than high self-efficacy tutors with high rapport with their tutees (m = .01, sd = .01).

This lends further support to our hypothesis that tutors with lower interpersonal closeness (here, rapport) with their tutees would use more indirectness with potentially face-threatening tutoring moves than those with greater interpersonal closeness. However, it is primarily the high self-efficacy tutors with low rapport with their tutees that appear to use this strategy, as they were marginally more likely (U = 928, p = .07) to use more indirect instructions (m = .03, sd = .02) than low self-efficacy tutors with low rapport with their tutees (m = .01, sd = .01). This also lends support to the hypothesis that greater self-efficacy for tutoring may allow the tutors to strategically use indirectness to fulfill interpersonal goals (i.e. mitigating face-threat). See Fig. 2 for the interaction effect between rapport and self-efficacy on tutors’ indirect instructions.

We then ran the same univariate test on tutors’ use of indirect comprehension-monitoring, finding a highly significant interaction effect of relationship and self-efficacy on the tutors’ use of indirect comprehension-monitoring (F(1,35) = 8.86, p < .01). Much like the effect of rapport on indirect instructions, tutors who are strangers are more likely to deliver their comprehension-monitoring indirectly when they have high tutoring self-efficacy. However, no pairwise comparisons were significant.

Impact of peer tutors’ indirect tutoring moves on tutees’ learning

Finally, we investigated our research question about the effect of tutors’ use of indirect instructions and comprehension-monitoring on tutees’ learning process and outcomes (RQ3). From prior literature on the motivational benefits of face-threat mitigation, we hypothesize that there will be an interaction between a dyad’s interpersonal closeness and their use of indirect tutoring language on learning outcomes. Specifically, we hypothesize that in dyads with low interpersonal closeness (stranger dyads and low-rapport dyads (both friend and stranger)), when tutors use more indirect tutoring moves, their tutees will attempt and solve more problems and will learn more from pre- to post-test (Kerssen-Griep et al. 2008; Roscoe and Chi 2008). An alternative hypothesis is that more direct feedback, instructions, and comprehension monitoring is associated with improved problem solving and learning, following Person et al. (1995)‘s findings that indirectness may lead to ambiguity in closed-world domains like algebra.

We thus ran a linear mixed-effect model using the tutees’ percent of problems solved in each tutoring period as the dependent variable, and using the tutors’ normalized frequency of indirect instructions and indirect comprehension-monitoring as fixed effects, along with interaction terms for each of the above with Relationship and Rapport, with random effects for Dyad and Session. We also included normalized frequency of the tutees’ self-explanations as a fixed effect, following the findings of Madaio et al. (2016) that tutees’ self-explanations were a significant predictor of their learning. We also included the frequency of direct instructions and comprehension-monitoring (in addition to the indirect versions of those moves) as fixed effects to identify the impact of that directness on tutee learning. As detailed in the methods, the direct instructions and comprehension-monitoring were the remainder of the tutoring moves of those types without a co-occurring annotation of indirectness. In this model, stranger tutors’ use of indirect instructions was positively predictive (β = .64, p < .05) of their tutees’ problem-solving. No other factors were significant. All model parameters for the problems solved model are reported in Table 2.

We further investigated whether the use of indirectness with instructions and feedback might serve a motivational role, leading to an increased amount of problems attempted for the tutee. We thus ran the same mixed-effects model, but with the tutees’ percent of problems attempted as the dependent variable. In this model, stranger tutors’ use of indirect instructions was also significantly positively predictive (β = .84, p < .01) of their tutees’ amount of problems attempted. No other factors were significant. All model parameters for the problems attempted model are reported in Table 3.

In addition to the shorter-term benefits of problem-solving during the tutoring interaction, we also wanted to investigate whether all of this hedging was beneficial for the tutees’ learning gains from pre- to post-test. We thus ran a linear mixed effect model with tutees’ overall learning gains as the dependent variable, and with the same fixed effects (tutors’ indirect and direct tutoring moves, and tutees’ self-explanation) and random effects (Dyad and Session) as described above. In this model, stranger tutors’ use of indirect comprehension-monitoring on their partners’ knowledge was positively predictive (β = .29, p = .05) of their tutees’ overall learning gains, with the only other effect being a marginal negative association (β = −.43, p = .09) of tutors’ direct instructions with their tutees’ learning gains. All model parameters for the learning gains model are reported in Table 4.

Tutees’ responses to tutors’ hedged instructions

These results show potential for hedged instructions and comprehension-monitoring to improve learning for some students in peer tutoring (perhaps due to the mitigation of face-threat). We then wanted to look deeper to understand how the tutees responded to these hedged dialogue moves, and how those responses differ by the interpersonal closeness of the dyad, to better understand how the hedged instructions impact the tutees’ problem-solving process. We therefore used an adjacency pair approach, following Boyer et al. (2009) to identify the most common tutee responses to tutor moves.

While a thorough analysis of all of the possible tutee responses to tutors’ moves is beyond the scope of this article, we will discuss here the adjacency pairs that included tutees’ responses to the indirect and direct instructions used by their partners. We extracted all of the tutees’ responses to their tutors’ use of indirect instructions as well as direct instructions, to identify differences in the way tutees with greater interpersonal closeness responded to the same type of tutoring move delivered directly and indirectly. We normalized the frequency of these adjacency pairs by the total number of moves included in the pair (e.g. tutors’ direct instructions and tutees’ self-explanations) similar to our approach in RQ2. This was due to the large variance in the distribution of the tutoring and learning behavior types included in the adjacency pairs.

For peer tutoring dyads with low rapport, tutees are significantly more likely (t(21.4) = 2.3, p = .03) to respond to their tutors’ indirect instructions with self-explanations than to respond to direct instructions with self-explanations. Specifically, tutees in low-rapport dyads respond to indirect instructions with their own verbalized self-explanations three times as often (m = .007) as they respond to tutors’ direct instructions with self-explanations (m = .002). This provides support for the hypothesis that indirect instructions are beneficial for tutees’ problem-solving in low rapport dyads. Crucially, however, there were no significant differences in the ways tutees responded to indirect instructions in high-rapport dyads. That is, while tutors’ hedged instructions led to increases in tutee self-explanations, this benefit only accrued for low-rapport dyads.

Discussion

In this article, we investigated the extent to which peer tutors’ instructional self-efficacy and domain knowledge intersect with their interpersonal closeness (both short- and long-term) with their tutee to impact the process and outcomes of peer tutoring, through peer tutors’ hedging of potentially face-threatening tutoring moves. Critical components of the collaborative learning process, such as providing procedural instructions, feedback, and monitoring their partners’ comprehension, have been postulated to be more likely to be avoided by peers due to the potential for those moves to threaten their partners’ “face”, particularly for peers with a more distant relationship with their partner (Brown and Levinson 1987; Person et al. 1995).

Here, the differences we found in tutors’ use of indirectness with various tutoring behaviors suggests that interpersonal, relational aspects of collaborative learning interactions like reciprocal peer tutoring are likely to impact the process by which students pursue their pedagogical task goals. For instance, although stranger tutors used more positive feedback than friends, their tutees were not solving significantly more problems correctly than friend-only dyads. This suggests that those tutors may be using that positive feedback to boost their partners’ face rather than accurately diagnosing the correctness of their partners’ problem-solving. This indicates that, while that positive feedback may serve a relational, face-boosting role, it may not serve a pedagogically useful role, and may even, as Person et al. (1995) pointed out, lead to ambiguity about the correct procedures or answers, possibly eroding the tutee’s trust in their tutor over time.

However, some peer tutors, particularly those with greater self-efficacy in their own tutoring abilities, may be able to modulate their delivery of those tutoring moves to mitigate their potential face-threat, through hedging, qualifying, subjectivizing, or other forms of indirect delivery. It was not the case, as we hypothesized, that tutors with lower domain knowledge and instructional self-efficacy hedged more. In fact, we found instead that peer tutors with greater self-efficacy were more likely to hedge their face-threatening tutoring moves, but only when they had lower interpersonal closeness with their tutee (both relationship and rapport). This suggests that that hedging was serving an interpersonal function, rather than indicating tutors’ uncertainty about the tutoring strategies they were using. We also found that only tutees with low interpersonal closeness with their tutors benefited from such hedging of instructions and comprehension-monitoring. This suggests that peer tutors with greater instructional self-efficacy have a greater ability to attend to interpersonal as well as instructional goals, and that this self-efficacy may allow them to engage in beneficial interpersonal tactics, such as face-threat mitigation through indirectness, that might otherwise be avoided if their confidence in their tutoring abilities were lower. More broadly, this work contributes to a more robust understanding of the ways in which interpersonal closeness and instructional self-efficacy intersect to impact the collaborative learning process, by way of reciprocal peer tutors’ use of an indirect delivery style with tutoring strategies.

Researchers and designers of computer-supported collaborative learning (CSCL) systems should thus be aware of how the interactional goals of tutoring may be impacted by the interpersonal goal of face-threat mitigation: specifically, through peer tutors’ overuse of positive feedback or through their strategic use of hedging when delivering instructions and explicit comprehension-monitoring. As Carmien et al. (2007) pointed out, while CSCL systems may provide external scripts for students to follow, these scripts may conflict with the internal scripts that students bring to bear on the interaction. As we found here, students’ interpersonal closeness with their partners provides one influencing factor on their interactional behaviors. Thus, a CSCL system that does not take into account the interpersonal closeness between collaborating students may find that the interactional support it provides to students conflicts with their interpersonal goals (i.e. mitigating face-threat). That is, a CSCL system that recommends that students explicitly reflect on each other’s knowledge or comprehension, perhaps similar to Weinberger et al.’s work on argumentative discourse (Weinberger et al. 2005) may find that students are hesitant to provide such reflection, depending on the directness with which it’s phrased. Some peer tutors, in addition, such as the lower self-efficacy tutors we saw here, may need more scaffolding and support from a CSCL system to deliver their tutoring moves in more interpersonally sensitive ways.

The selection, frequency of use, and delivery style of pedagogical behaviors used by collaborating students may differ depending on whether the collaborating students are friends or strangers, or have a greater or lower rapport, and those same behaviors may have different impacts on student learning, depending on that interpersonal closeness. Designers of collaborative systems, such as Olsen et al.’s (2014) collaborative intelligent tutoring system or Walker et al.’s (2011) adaptive collaborative learning system, might therefore build in awareness of the interpersonal closeness between students. In addition to cognitive instructional supports, such systems might provide social, interpersonal supports, such as recommending students phrase their instructions or comprehension-monitoring to each other more indirectly when interpersonal closeness is lower, particularly for tutors with lower self-reported self-efficacy. However, these recommendations run the risk of overscripting (Dillenbourg 2002), and should thus be used judiciously.

These findings can also inform the design of collaborative dialogue systems, with conversational agents that could support collaborative learning by modeling different ways of delivering instructions, feedback, comprehension-monitoring, or other potentially face-threatening instructional moves. Such agents have been used in prior CSCL work as in Tegos et al. (2016) and Wang et al. (2017) to promote students’ academically productive talk and transactive talk, respectively. Those conversational agents might detect the interpersonal dynamics among the students and between students and the conversational agent and recommend interpersonal moves (such as indirectness) to fulfill interpersonal goals in addition to the interactional goals of learning. One such rapport-building system is the “Socially-Aware Robot Assistant”, or S.A.R.A., system (Matsuyama et al., 2016; Zhao et al. 2014; Sinha and Cassell 2015), which uses a set of social conversational strategies to build a deeper rapport with its users over time. To that end, as one way to detect the interpersonal closeness described here, Yu et al. (2013) developed a method for the automatic prediction of friendship, which we found (the lack of) here to be a significant predictor of indirect instructions and comprehension-monitoring. For the shorter-term closeness of rapport, which we found to be a significant predictor of indirect instructions, Zhao et al. (2016) have developed a method for the automatic detection of rapport based on temporal association rules between multimodal data such as students’ social conversational moves and nonverbal behaviors and the subsequent change in their rapport, which Madaio et al. (2017) extended to include the tutoring and learning behaviors of a peer tutoring dyad to detect their rapport.

Limitations and future work

This work is part of a larger research program to understand the ways in which interpersonal rapport may impact teaching and learning, and it is already being used to inform the design of conversational agents that simulate a peer tutor as the front end of an intelligent tutoring system. Such a virtual agent could collaborate on teams with students in the ways that a peer would, while playing the role of a peer tutor. This goal is furthered by studying the process of rapport development in peer tutoring, implementing that model in the agent’s dialogue management, and, perhaps, by reducing the face-threat of particular instructional moves when necessary by delivering those tutoring strategies indirectly, in socially appropriate ways.

One of the limitations of the study reported in this article is the small sample size, particularly for dyads of strangers. While a path analysis may have elucidated possible mediation effects from interpersonal closeness to tutoring moves to tutee learning, we did not find such effects, perhaps due to the low power of our small sample size. We have thus recently finished conducting a similar study with 22 dyads of strangers to better understand how the rapport-building process develops within dyads starting from the same interpersonal baseline, and how that rapport impacts their teaching and learning processes and outcomes. Another limitation of this work is the culturally dependent nature of what may be perceived as face-threatening or indirect by the interlocutors (Spencer-Oatey 2005). While we did not code for face-threat here, future work may provide an operationalization of the face-threat of each utterance (following Cassell and Bickmore 2003) to investigate the putative mechanism by which directness and indirectness may impact student learning. Thus, future work exploring this face-threat should take into account how the culture of the participants impacts perceptions of face-threat and indirectness (and how the culture of the annotators may impact their annotation). Ogan et al., (2015), among others, have already begun to explore how the collaboration process differs from culture to culture, studying how students collaborate while using intelligent tutoring systems in Chile and the United States, among other countries.

We are also currently involved in investigating other potentially face-threatening pedagogical behaviors, to understand whether and how high-rapport dyads engage in, for instance, cognitive conflict, help-seeking, help-offering, and others. In this article, while we used the normalized aggregate frequency of a particular set of annotated behaviors to understand differences between groups of dyads, some of the most beneficial tutoring behaviors may occur infrequently or may have their benefits impacted by the contingent patterns of use and response from their partner (Ohlsson et al. 2007). Therefore, an analysis that does not take this contingent, temporal pattern of use into account may miss important effects. In this article, we have begun to analyze these contingent response patterns by using an analysis of the adjacency pairs between tutor and tutee. We are currently building on this approach by using temporal association and sequence mining approaches to identify the core sequences of pedagogical and social behaviors that contribute to greater rapport and learning.

We intend this article to contribute to the body of knowledge on the impact of social bonds on the process of collaborative learning, as well as contributing to the design of socially-aware computer-supported collaborative learning systems, which can more appropriately respond to learners’ social bonds in pedagogically beneficial ways, and vice-versa.

References

Ambady, N., & Rosenthal, R. (1992). Thin slices of expressive behavior as predictors of interpersonal consequences: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 111(2), 256 1992.

Benjamini, Y., & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B: Methodological, 57(1), 289–300.

Brown, P., & Levinson, S. C. (1987). Politeness: Some universals in language use (Vol. 4). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Boyer, K. E., Phillips, R., Ha, E. Y., Wallis, M. D., Vouk, M. A., & Lester, J. C. (2009). Modeling dialogue structure with adjacency pair analysis and hidden Markov models. Proceedings of NAACL HLT (Short Papers), 19–26. https://doi.org/10.3115/1620853.1620869.

Carmien, S., Kollar, I., Fischer, G., & Fischer, F. (2007). The interplay of internal and external scripts. Scripting Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 6, 303–326.

Cassell, J., & Bickmore, T. (2003). Negotiated collusion: Modeling social language and its relationship effects in intelligent agents. User Modeling and User-Adapted Interaction, 13(1), 89–132.

Chi, M. T. H. (1997). Quantifying qualitative analyses of verbal data: A practical guide. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 6(3), 271–315.

Coates, J. (1987). Epistemic modality and spoken discourse. Transactions of the Philological Society, 85(1):110–131.

Dame, N., & Tynan, R. (2005). The effects of threat sensitivity and face giving on dyadic psychological safety and upward communication. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 35(2), 223–247.

Dillenbourg, P. (2002). Over-scripting CSCL: The risks of blending collaborative learning with instructional design. P. A. Kirschner. Three worlds of CSCL. Can we support CSCL?, Heerlen, Open Universiteit Nederland, pp.61-91.

Dillenbourg, P. (2015). Orchestration graphs: Modeling scalable education. Lausanne: EPFL Press.

Feng, B., & Magen, E. (2015). Relationship closeness predicts unsolicited advice giving in supportive interactions. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 33(6), 751–767.

Fraser, B. (2010). Pragmatic competence: The case of hedging. New Approaches to Hedging, 9, 15–34.

Gibson, S., & Dembo, M. H. (1984). Teacher efficacy: A construct validation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 76(4), 569.

Goffman, E. (2016). On face-work. Psychiatry, 18(3), 213–231.

Johnson, W. L., & Rizzo, P. (2004). Politeness in tutoring dialogs: Run the factory, that’s what I’d do. In Seventh International Conference on Intelligent Tutoring Systems (pp. 67–76). Maceió.

Kerssen-Griep, J., Trees, A. R., & Hess, J. A. (2008). Attentive Facework during instructional feedback: Key to perceiving mentorship and an optimal learning environment. Communication Education, 57(3), 312–332.

Kruger, J., Endriss, U., Fernández, R., & Qing, C. (2014). Axiomatic analysis of aggregation methods for collective annotation. In Proceedings of the 2014 international Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multi-Agent Systems (pp. 1185-1192). International Foundation for Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems.

Madaio, M. A., Ogan, A., & Cassell, J. (2016). The effect of friendship and tutoring roles on reciprocal peer tutoring strategies. In International Conference on Intelligent Tutoring Systems (pp. 423-429). Springer, Cham.

Madaio, M., Ogan, A., & Cassell, J. (2017). Using Temporal Association Rule Mining to Predict Dyadic Rapport in Peer Tutoring. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Educational Data Mining, http://educationaldatamining.org/EDM2017/proc_files/papers/paper_118.pdf.

Matsuyama, Y., Bhardwaj, A., Zhao, R., Romero, O.J., Akoju, S., & Cassell, J. (2016). Socially-aware animated intelligent personal assistant agent. In 17th Annual SIGdial Meeting on Discourse and Dialogue. Pittsburgh: Carnegie Mellon University.

Mojavezi, A., & Tamiz, M. P. (2012). The impact of teacher self-efficacy on the students’ motivation and achievement. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 2(3), 483–491.

Morand, D. A., & Ocker, R. J. (2003). Politeness theory and computer-mediated communication: A sociolinguistic approach to analyzing relational messages. In System Sciences, 2003. Proceedings of the 36th Annual Hawaii International Conference on (pp. 10-pp). IEEE.

Mottet, T. P., & Beebe, S. A. (2002). Relationships between teacher nonverbal immediacy, student emotional response, and perceived student learning. Communication Research Reports, 19(1), 77–88.

Neary-Sundquist, C. (2013). The use of hedges in the speech of ESL learners. Elia: Estudios de Lingüística Inglesa Aplicada, 13, 149–174.

Ogan, A., Finkelstein, S., Walker, E., Carlson, R., & Cassell, J. (2012). Rudeness and rapport: Insults and learning gains in peer tutoring. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Intelligent Tutoring Systems (pp. 11–21). Berlin: Springer.

Ogan, A., Walker, E., Baker, R., Rodrigo, M. M. T., Soriano, J. C., & Castro, M. J. (2015). Towards understanding how to assess help-seeking behavior across cultures. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 25(2), 229–248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-014-0034-8.

Ohlsson, S., Di Eugenio, B., Chow, B., Fossati, D., Lu, X., & Kershaw, T.C. (2007). Beyond the code-and-count analysis of tutoring dialogues. In Proceedings of the 2007 Conference on AI in Education, 158, p. 349.

Olsen, J. K., Belenky, D. M., Aleven, V., & Rummel, N. (2014). Using an intelligent tutoring system to support collaborative as well as individual learning. In International Conference on Intelligent Tutoring Systems (pp. 134-143). Springer, Cham.

Palinscar, A. S., & Brown, A. L. (1984). Reciprocal teaching of comprehension-fostering and comprehension-monitoring activities. Cognition and Instruction, 1(2), 117–175.

Person, N. K., Kreuz, R. J., Zwaan, R. A., & Graesser, A. C. (1995). Pragmatics and pedagogy: Conversational rules and politeness strategies may inhibit effective tutoring. Cognition and Instruction, 13(2), 161–168.

Prince, E., Frader, J. & Bosk, C. (1982). On hedging in physician-physician discourse. In R. J. Di Pietro (Ed.), Linguistics and the professions. Proceedings of the second annual delaware symposium on language studies (pp. 83–97). Norwood: Ablex.

Ray, D. G., Neugebauer, J., Sassenberg, K., Buder, J., & Hesse, F. W. (2013). Motivated shortcomings in explanation: The role of comparative self-evaluation and awareness of explanation recipient's knowledge. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 142(2), 445.

Roscoe, R. D., & Chi, M. T. H. (2008). Tutor learning: The role of explaining and responding to questions. Instructional Science, 36(4), 321–350.

Rowan, B., Chiang, F., & Miller, R. (1997). Using research on Employees' performance to study the effects of teachers on Students' achievement. Sociology of Education, 70(4), 256–284.

Rowland, T. (2007). ‘Well maybe not exactly, but it’s around fifty basically?’: Vague language in mathematics classrooms. In J. Cutting (ed.), Vague language explored (pp. 79–96). Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan

Saklofske, D. H., Michayluk, J. O., & Randhawa, B. S. (1988). Teachers' efficacy and teaching behaviors. Psychological Reports, 63(2), 407–414.

Sinha, T. (2016). Cognitive Correlates of Rapport Dynamics in Longitudinal Peer Tutoring. Available at http://tinyurl.com/RapportDynamicsSinha2016.

Sinha, T., & Cassell, J. (2015). We click, we align, we learn: Impact of influence and convergence processes on student learning and rapport building. In Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on Modeling INTERPERsonal SynchrONy And infLuence (pp. 13-20). ACM.

Spencer-Oatey, H. (2005). (Im)Politeness, face and perceptions of rapport: Unpackaging their bases and interrelationships. Politeness Research, 1(1), 95–119.

Tegos, S., Demetriadis, S., Papadopoulos, P. M., & Weinberger, A. (2016). Conversational agents for academically productive talk: A comparison of directed and undirected agent interventions. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 11(4), 417–440.

Tickle-Degnen, L., & Rosenthal, R. (1990). The nature of rapport and its nonverbal correlates. Psychological Inquiry, 1(4), 285–293.

Tracy, K., & Coupland, N. (1990). Multiple goals in discourse: An overview of issues. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 9(1–2), 1–13.

Walker, E., Rummel, N., & Koedinger, K. R. (2011). Designing automated adaptive support to improve student helping behaviors in a peer tutoring activity. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 6(2), 279–306.

Wang, X., Wen, M., & Rose, C. (2017). Contrasting Explicit and Implicit Support for Transactive Exchange in Team Oriented Project Based Learning In Smith, B. K., Borge, M., Mercier, E., and Lim, K. Y. (Eds.). (2017). Making a difference: Prioritizing equity and access in CSCL, 12th International conference on computer supported collaborative learning (CSCL) 2017, Volume 1. Philadelphia: International Society of the Learning Sciences.

Weinberger, A., Ertl, B., Fischer, F., & Mandl, H. (2005). Epistemic and social scripts in computer–supported collaborative learning. Instructional Science, 33(1), 1–30.

Wichmann, A., & Rummel, N. (2013). Improving revision in wiki-based writing: Coordination pays off. Computers in Education, 62, 262–270.

Yu, Z., Gerritsen, D., Ogan, A., Black, A., & Cassell, J. (2013). Automatic prediction of friendship via multi-modeldyadic features. In 14th Annual SIGdial Meeting on Discourse and Dialogue. Metz: Association for Computational Linguistics.

Zhang, G. (2013). The impact of touchy topics on vague language use. Journal of Asian Pacific Communication, 23(1), 87–118.

Zhao, R., Papangelis, A., & Cassell, J. (2014). Towards a dyadic computational model of rapport management for human-virtual agent interaction. In International Conference on Intelligent Virtual Agents (pp. 514-527). Springer, Cham.

Zhao, R., Sinha, T., Black, A. W., & Cassell, J. (2016). Socially-aware virtual agents: Automatically assessing dyadic rapport from temporal patterns of behavior. In International Conference on Intelligent Virtual Agents (pp. 218-233). Springer International Publishing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Madaio, M., Cassell, J. & Ogan, A. “I think you just got mixed up”: confident peer tutors hedge to support partners’ face needs. Intern. J. Comput.-Support. Collab. Learn 12, 401–421 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-017-9266-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-017-9266-6