Abstract

Organisational resilience has become an increasingly important topic for businesses in recent years, as disruptions and unexpected events can have a significant impact on their operations, reputation, and financial performance. Such were the case with the COVID-19 pandemic, the cyberattacks on essential services or the recent conflict in Ukraine, all of which entail long-term disruptions that affect strategic business objectives. To ensure continuity of operations, it is essential to establish a comprehensive approach to enterprise risk management and increase resilience through internationally recognised standards such as COSO-ERM, ISO 31000, ISO 28000 or ISO 22316. The objective of this study will be to test a maturity model that will provide scientific support to professionals and, to a greater extent, to companies and other organisations. It assesses an organisation's security and resilience management system maturity level against internationally-recognised standards, with this model allowing them to visualise its evolution in subsequent updates. The proposed model has been tested through a survey that was carried out anonymously among the main companies included in the Spanish IBEX 35 stock index. It is an innovative model that can pave the way for new trends in entrepreneurship and management in terms of organisational resilience, after being empirically tested in a real business environment. It is also a direct transfer to the industry and allows for the creation of new strategies in service operations that support resilience.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

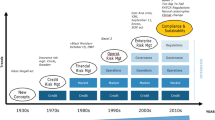

The relationship between security and resilience is reflected in the publication of international standards, such as ISO 22316 'Security and resilience – Organisational resilience – Principles and attributes' (ISO, 2017) as well as in academic literature (Braes & Brooks, 2011; Thompson et al., 2016; Trucco & Petrenj, 2017). According to ISO 22316, “enhancing resilience…is the outcome of good business practice and effectively managing risk”, which seems to indicate the intention of ISO/TC 292's working group, WG 2, to create a framework that involves three concepts: security, resilience, and risk. Previous research by the authors on security risk management and organisational resilience (Marquez-Tejon et al., 2022) through a comprehensive bibliometric study concluded that, over the last three decades, the discipline of security risk management has established itself both as a subject area in its own right and as a field closely linked to enterprise risk management (hereafter ERM). Amongst its conclusions, it was considered relevant to further explore the current contribution to organisational resilience (hereafter OR) by a security management system based on Enterprise Security Risk Management (hereafter ESRM). Typically, the security function in large enterprise corporations has provided cross-cutting support at the strategic level during crisis management to minimise the impact on business objectives (Ludbey et al., 2018), and even international security associations have contributed to the development of several international standards on resilience and business continuity (ANSI/ASIS, 2017; ASIS, 2021).

In a later study (Marquez-Tejon et al., 2023), it was observed that security risk in organisations would come under the, what is known as, operational risks and that the security function, besides managing those risks within its scope, may also be assigned a transversal function through which it exercises governance of the preparedness and response strategies associated with the OR. This encompasses not only risk management but also the management of response plans associated with crisis management, business continuity and incident management.

Although there is an emerging academic production of specific models that determine the maturity of different management systems, there was a gap in terms of the security management system’s maturity models linked to the governance of OR and ERM, which would also facilitate their practical inclusion in the organisation's integrated management system. To help bridge this gap, an OR management system maturity model, through the security function called ERMsec© (Marquez-Tejon et al., 2023), was proposed to provide scientific support to practitioners and, to a greater extent, to companies and other organisations regardless of their size, sector of activity or geographical location.

It was also highlighted from the literature review that, in general, those organisations with multiple management systems receive more benefits than those that implemented only one standard or are managed separately in silos. While there is no single quick fix, single process, management system nor software application that creates resilience (Gibson & Tarrant, 2010), it does not preclude organisations from being able to establish the sweet spot they want to achieve in line with their strategic objectives. Based on the ERMsec© model, a questionnaire has been developed using the Capability Maturity Model Integration (hereinafter CMMI) system developed by Carnegie Mellon University (CMMI Institute, 2020), which establishes 5 levels of process maturity. The next step, which is the focus of this paper, will consist of testing this questionnaire through a quantitative research process involving surveying large business organisations. This surveying was carried out anonymously among some of the largest companies in Spain, using a method that guarantees both the reliability and quality of the data provided.

The survey's main objective is to assess the level of maturity of an organisation's security and resilience management system concerning internationally-recognised standards, through a model that allows the evolution of its results to be visualised in subsequent updates. Other secondary objectives, such as studying the position of the senior security executive in the organisation's hierarchy, as well as training needs or the inclusion of the business intelligence discipline within the OR and security processes, are also pursued.

Theoretical framework

The term “resilience” is applied, at different levels, to describe the capacity to cope with often sudden and dramatic changes at individual, community, societal and organisational levels. In this study, we will consider only its organisational aspect, whose academic interest has grown steadily in recent years, although the conceptualisation of the construct has yet to be developed. (Duchek, 2019; Gibson & Tarrant, 2010; Hillmann & Guenther, 2021a; Saunders & Becker, 2015). As for its etymological origin, resilience comes from the Latin verb “resilio”, which translates to “to jump back, to bounce back” and is used in physics to explain materials that bend without breaking and then return to their original state or shape, as if nothing had happened. However, at the organisational level, rather than a rebound backwards that entirely replicates the previous state, it is an ability to encourage a rebound forward (Siambabala et al., 2011) but enriched with the experience gained during the response and recovery from the disruptive event, whether it was a foreseen scenario or a novel one. The adaptation that occurs during recovery from a disruptive event implies that it does not have to return to its previous state as such, but evolve to cope with changing circumstances in seamless synergy with sustainability (Saunders & Becker, 2015).

The development of this organisational dimension has been academically focused on thematic areas such as sustainability, communications, competitive excellence or supply chains (Falasca et al., 2008; McManus, 2008; Ogrean, 2018; Settembre-Blundo et al., 2021; Stephenson, 2010), and even on the relationship between resilience and entrepreneurship (Omorede, 2021; Skare & Porada-Rochon, 2021); although the literature on entrepreneurship has not moved beyond conceptual work and inconclusive assumptions (Hillmann & Guenther, 2021b).

Resilience has been recognised by organisations as a top priority or highly relevant to strategic decision-making (FERMA, 2021). Organisations with a higher level of internal resilience can better mobilise resources, allocate staff and prioritise key functions, without fear of making difficult decisions through evidence-based intelligence and analysis (Gracey, 2020; McManus, 2008; Stephenson, 2010). Organisations with greater strategic resilience are able to adapt in the face of threats to their long-term strategy or objectives, coming back stronger from the experience (Hepfer & Lawrence, 2022). However, organisations need to go beyond conceptualisation and “get down to business” to make it truly practical, both in terms of the process and the capabilities involved in building resilient organisations (Slagmulder, 2022).

Conceptually, OR is widely standardised at the international level (BSI, 2014; Commonwealth of Australia, 2016; ANSI/ASIS, 2017; ISO, 2017). According to ISO 22316 the resilience of an organization is influenced by a unique interaction and a combination of strategic and operational factors. Previous studies on literature related to OR have found that, although such a division between strategic and operational factors of OR is already apparent, only some operational ones have been developed further. Such is the case of resilience associated with sectors such as banking (Leo, 2020) or supply chain (Annarelli & Nonino, 2016); driven perhaps, in the first instance, by a need of regulators and banking operators derived from the latest financial crises and supply chain disruptions at the global level. This is why we consider the operational side of resilience to be already broadly defined (Bank of England, 2021; Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, 2021; Central Bank of Ireland, 2021; Federal Reserve Board, 2020) and closely associated with operational risks (Milkau, 2021).

To understand the strategic aspect of OR, one must consider the causal relationship between risks and resilience as shown in Fig. 1. While resilience management does not depend on risk considerations and assessments to be effective, it could benefit from such considerations and assessments if carried out correctly, thus forging a causal relationship between risk management and resilience; in the sense that, without the former, the functionality of resilience is compromised (Aven, 2017). We can define strategic resilience as an "organisation's ability to anticipate and respond to threats to its strategy, and especially its long-term goals and thus its survival". (Hepfer & Lawrence, 2022) These threats are included in the COSO-ERM standard (COSO, 2017) which aims to cover different risk categories: business strategic, financial, compliance and operational (Arena et al., 2014). While there is no clear agreement on the definition of strategic risk (Cooper & Faseruk, 2011), the first three risks encompass the threats that meet this definition of strategic resilience, including specific compliance and financial risks, all of which have been evolving towards this strategic aspect (Gates, 2006).

Empirical study

Some authors have studied the academic/scientific research methodology in contrast to other methodologies used by operational management researchers more interested in solving relevant and specific problems (Will et al., 2002). In this paper, academic studies on the methodology of quantitative research (Casas Anguita et al., 2003a, b; López-Roldán & Fachelli, 2015) have been taken as a reference, establishing nine stages in the research planning (see Fig. 2), and using the survey technique (Santesmases Mestre, 2009). Of these nine stages, the last one called "data analysis and interpretation of results" will be developed later in the results and discussion sections.

Identifying the problem

Business activity is subject to risks in an environment of uncertainty, some of which are related to security. Risk management must be integrated with the organisation's global risk strategy, together with the rest of the corporate and business areas. This is becoming increasingly important, especially in large organisations. Hence, this study’s main approach is, on the one hand, to analyse security risk management and resilience in companies, based on the ERMSec© model (Marquez-Tejon et al., 2023) obtained from internationally-recognised standards (ISO 2236, ISO 22301, ISO 22320, ISO 31000 or ISO 28000, among others); mainly those included in the main benchmark of the Spanish stock market "IBEX 35" (BME, 2022a); and, on the other hand, to diagnose their strategic contribution to the resilience of their organisation.

Main objective:

MO

To assess the maturity level of an organisation's security and resilience management system against internationally-recognised standards.

Secondary objectives:

SO1

To explore the security organisation model in leading Spanish companies, in particular the position of the senior security executive in the organisational hierarchy.

SO2

To study the inclusion of OR and intelligence operations within the security management system.

SO3

To study the inclusion of OR and intelligence operations within the security management system.

SO4

To compare security and resilience management systems in different business sectors.

Determining the research design

Taking Sierra's classification of surveys as a reference (Sierra Bravo, 2007), the social research technique selected for this research is the quantitative survey, which will be complemented by other aspects of this classification (see Fig. 3):

Type of Social Research based on Sierra Bravo (Sierra Bravo, 2007)

Specifying the hypotheses

We hypothesise that:

H1. The maturity of the security and resilience management system in this type of company is very high. It is supported in its implementation by senior management and aligned with the strategic objectives of the organisation.

H2. Large Spanish companies, many of which are listed on the Spanish stock exchange, manage their security and resilience through a management system led by a formally constituted security department.

Defining the variables

According to Medianero Burga (2014), a variable is a magnitude whose values are the object of study, and its definition makes what is to be evaluated susceptible to measurement. This variable, in turn, consists of five elements (see Fig. 4): name, operational definition, variable number, reference measurement criterion, and the value of the variable. Once the data has been collected, the indicators can be obtained (see Fig. 5). To measure the variables, it is necessary to indicate the measurement scale that will be used in the processing of the information. In the ERMsec© tool, requirements have been included in each variable that will serve as a reference to obtain a value associated with the CMMI maturity level. For example, if any one of the requirements is fulfilled, the value of the variable will be “1” in the CMMI maturity level; and if all the requirements are fulfilled, the value will be “5”.

Sample selection

As an inclusion criterion for this study, it has been determined that the companies to be interviewed must be included in the Madrid stock exchange index, preferably in the IBEX 35, which will reduce the size of the sample. A stock market index is a numerical benchmark that reflects the evolution of the prices of these securities over time, and which is formed from the most significant listed securities in an economy at a given point in time (Palacios Bascón & Rodríguez Muñoz, 2020).

The list of companies was retrieved from the Madrid Stock Exchange website, including the sectors to which each company belongs. Eleven companies were finally selected from four of the seven sectors defined by the stock exchange (BME, 2022b): Oil and Energy; Consumer Services; Financial Services; and Technology and Telecommunications. The decision to limit the survey to these four sectors is primarily motivated by the benchmark set by the Spanish state, in relation to state security and the continuity of essential services for society. Thus, it established priorities within its strategy for the implementation of the critical infrastructure protection system, which has already been implemented with 18 sectoral strategic plans (CNPIC, 2021). Secondly, given the size of the selected companies, it is assumed that they have established resilience strategies through their respective security functional departments in collaboration with their business risk managers and other functions within their organisation. These two conditions are intended to prove that they should already have a high level of maturity according to the parameters of the ERMsec© tool.

Designing the questionnaire

The instructions and formulation of questions are the same for all participants and the data is collected using a questionnaire, so that comparisons can be made between the different subgroups of the study that constitute the 4 selected sectors of activity: Oil and Energy; Consumer Services; Financial Services; and Technology and Telecommunications.

Survey questions

The questionnaire is divided into two sections. The first section (see Tab. 1) contains questions that will allow us to compare organisations according to their positioning in the market, sector of activity, resources allocated to the functional unit, and the position of its Senior Security Executive and their department in the organisation's hierarchy. Meanwhile, the second section contains questions that will allow for specific data to be obtained on the management system itself, and the assessments that will result in both the partial result of each of the questions and the total result of the questionnaire. The result of each of the seven clauses in Fig. 5 will be the average of the questions that comprises it and will be represented as a graph, as in the model in Fig. 6.

In part 5 of the second section, which coincides with the “Do” of the Deming cycle, a proposal is made for resilience and security-related operations, which can be adapted to each organisation (see Fig. 5). In each of the resilience activities, the issues to be assessed should come from a standardised source, such as those related to the organisational resilience activity referred to in ISO 2236, ISO 22301 and ISO 22320. This means that to the “traditional” operation specific to the security function (5.1 Intelligence operation; 5.2 Information Security Operation; and 5.3 Protection of persons, assets, and information), we can add the “transversal” operation that develops the resilience response plans (5.4 Incident management; 5.5 Business Continuity; and 5.6 Crisis Management). The results will also take into account the specific results related to resilience, so that if the responsibility for this cross-cutting function falls on another function, the ERMsec© model can still be used.

It should be noted that it does not take into account who owns the risk (the function or the business unit) or who is responsible for its management, as the aim here is to visualise the status of the management system, either in the organisation as a whole or in a specific business unit.

Layout of the questions

According to the premises of the ERMsec© model (Marquez-Tejon et al., 2023), the questions are organised into two sections. The first consists of six initial control questions that help to frame the organisation within its geographical and activity sector (see Table 1). The second section consists of thirty-four questions distributed in seven sections that coincide with the seven clauses and are grouped in correlation with the PDCA cycle (see Fig. 5). The result of the second section determines the maturity level according to the Capability Maturity Model Integration scale initially developed by Carnegie Mellon University (CMMI Institute, 2020), in establishing 5 levels of process maturity: Non-Existent/Not Wanted (0); Ad Hoc (1); Repeatable (2); Defined (3); Managed (4); Optimised (5).

These two sections of the questionnaire will allow a comparison of the results obtained to determine whether the company's position in the market or sector, as well as the size of the resources, influence the maturity of the integrated security management system.

Graphs have also been incorporated in the results template to enhance its comprehension and, therefore, facilitate the determination of action plans to reach the desired target. In addition, it allows for the comparison of business units within the organisation itself, specific operations or comparisons with other organisations in its sector or area of influence. It would be recommended for better strategic governance to set a reference target to compare with the resulting value, as shown in Fig. 6, where the red line represents the target risk level previously defined by the organisation and the blue line represents the actual result of the survey. In this example, the results in the operation and performance evaluation clauses would be below the target level.

Organising fieldwork

The survey is carried out through personal interviews to ensure a high degree of response (León & Montero, 1993) and in this way, given that there is direct contact, clarifications can be made there and then. The length of the questionnaire may be a limiting factor given the amount of time needed per interviewer and interviewee. A framework of mutual trust is also required to guarantee anonymity, which may require prior formal or informal consent. As the questionnaire is included in a tool previously developed by the researcher, the result is immediately available, and an anonymised copy is provided to the interviewee.

The initial questionnaire was pilot-tested with one of the companies selected for the study, after which corrections were made. In order to reduce the questionnaire to 40 questions, an effort was made to identify the key cross-cutting compliance indicators of the international standards on which the proposed management system is based, especially in the section containing the management system assessments. The number of key indicators in this section of the management system can vary for each survey question, from 3 to 5, to help quantify the maturity level assessment (from 0 to 5).

Obtaining and processing the data

The data is coded according to the objective assessments and the sections of the questionnaire, and is entered into a computerised database for further statistical processing.

Results of the analysis

Results of the general data section

The data obtained from the second section, which contains the questions that help to frame the organisation within its geographical and activity sector, have been consolidated in Table 1. In relation to the second hypothesis, it is confirmed that all the companies surveyed have a security department duly formalised in accordance with the Spanish Private Security Law. During the interview process, it was corroborated through direct observation with the interviewees that their security departments were also involved in the governance of resilience within their management system. Of these, 73% belong to the Madrid stock market index, “IBEX 35”.

It was found that only 18% of senior security executives report directly to the CEO; 9% report to a member of the steering committee; 55% report to a manager who is not part of the steering committee; and 18% are at a fourth level in the company hierarchy. The hierarchical distance between the senior security executive and the CEO is significantly higher in the Financial Services sector. Moreover, the management/function to which the senior security executive reports most frequently is Resources (46%), while the other hierarchical units (direct to the CEO, Operations or People) share the same proportion each (18%). In terms of the weighted average number of security department staff by sector, Technology and Telecommunications is the highest (49%), while the lowest is Consumer Services (10%).

Specific results of the management system

The data obtained from the second section, which included questions related to the security and resilience management system, has been consolidated in Table 2. From this data, we can extract results that have allowed us to visualise the management system as a whole (including security and resilience operations), as well as separately (security or resilience). Both of which are presented in this paper, although the model also allows us to focus on a particular sector or area of the management system.

Security and resilience management system

As can be seen in Fig. 5, the total weighted score of the management system encompassing security and resilience is 4.63, where the lowest value is for the “Business Continuity” and “Crisis Management” operations (4.09) and the highest value (4.45) is for the “Intelligence” operation. Both the minimum and maximum values are within the “Managed” maturity level. In the radar graph (Fig. 6), level 3, which corresponds to the maturity level “Defined”, is marked in red. The values achieved are shown in blue, and it can be seen that they are in the highest section of level 4, corresponding to the “Managed” maturity level.

In relation to the first hypothesis raised in the study, the evaluation of the “Leadership” clause is very high (4.70). In its “Leadership and Commitment” section, its evaluation (4.73) took into account that the policies and objectives of the management system are aligned with the organisation's strategy; that it is integrated into the business processes; that the necessary resources are available; and that its importance has been communicated, and continuous improvement has been encouraged. Although the value for policy implementation stands out (4.82), it was noted during the interviews that there was no single resilience policy and that references to business continuity and crisis management were either embedded in the security policy itself, or were separated from security in separate policies in the form of a crisis management policy or business continuity policy.

Of the four sectors in the study (Oil and Energy; Consumer Services; Financial Services; and Technology and Telecommunications), the proportional value associated with “Leadership and Commitments” is slightly higher in the Financial Services sector, followed by the Oil and Energy sector. While the proportional value associated with “Planning” is notably higher in the Oil and Energy sector, followed by Financial Services.

The proportional value associated with the “Intelligence” operation is significantly higher in the Oil and Energy sector, followed by Financial Services. The difference, with respect to the other two sectors, is also repeated when we analyse the proportional value associated with having a specific security training programme for security department staff, which is again significantly higher in the Oil and Energy sector, followed by Financial Services.

Resilience management system

The result of the management system, taking into account only the sections exclusive to resilience operations (5.4 Incident Management; 5.5 Business Continuity; and 5.6 Crisis Management) is a weighted average of 4.6 (see Fig. 7), with the lowest value found in “Operation” (4.1) and the highest value (4.8) in “Context of the Organisation” and “Improvement”.

It is apparent that when the value of the “Support” clause is high, it corresponds to a high value in the “Risk assessment and Treatment” process. And that, in general, high values of “Support” lead to high values in the “Crisis Management” and “Business Continuity” operations.

Security management system

The result of the management system, taking into account only the sections exclusive to “traditional” security operations (5.1 Intelligence; 5.2 Information Security; and 5.3 Protection of persons and assets), is a weighted average of 4.6 (see Fig. 8), with the lowest value seen in “Operation” (4.4) and the highest (4.8) in “Context of the Organisation” and “Improvement”. In the radar graph, level 3 has been marked in red, corresponding to the “Defined” maturity level. The blue colour represents the values achieved and shows that they are in the highest section of level 4, corresponding to the “Managed” maturity level.

Training

82% of the companies surveyed have a specific security training or awareness plan for all the company's staff. Only 9% have it partially in place, and 9% do not have one. The same percentage (82%) has a specific security awareness or training plan for security department staff. 9% have it partially in place, and 9% do not have it at all. In the majority of the companies surveyed (91%), the training plan for security department staff includes organisational, operational, technological, and security risk management aspects.

64% feel that their organisation does not have all security training needs covered. 36% consider that this is the case. A total of 73% consider that the budget is one of the reasons for not being able to cover all of their security training needs, and that the lack of training in the market is, in 73% of the cases, another reason for not being able to cover security training needs.

A high value for “Training and Awareness” generally determines a high value for “Operation”. On the other hand, the “Training and Awareness” and “Crisis Management” fields appear to be highly dependent on each other.

Discussion

In the literature review of previous research on maturity models, it has been observed that the highest maturity level does not always mean that it is the best, but the objectives set should be consistent with the level of maturity achieved (Rosemann & De Bruin, 2005). The results have to be interpreted in terms of the moment the observation is made, as if we were taking a snapshot of that instant, which may be the first one in order to obtain the starting point or a later one to assess whether the previously planned objectives are being met. The results of the security and resilience management system (Fig. 5) show that the minimum and maximum values obtained are within the highest level of level 4, which corresponds to the “Managed” maturity level.

After analysing the results, it is clear that all the companies surveyed have a security department. But this does not necessarily mean that all large companies or companies listed on the Spanish stock market have a security department under the responsibility of a senior security executive. In fact, only some of them are obliged by Spanish law (Ministerio de Justicia e Interior, 2008), so the existence of such departments in “non-obliged” companies will depend on the needs and will of top management.

Although 18% of senior security executives report directly to the CEO and 9% to a senior executive on the steering committee, the security department is mainly located at a third or fourth hierarchical level within the organisation. The position to which the senior security executive reports to the greatest extent is to the Resources Directorate. Furthermore, in most of the companies surveyed, the senior security executive, while not reporting directly to the CEO, does have direct contact with the president or CEO of the company insofar as they directly manage its security (protection of people, protection of sensitive information, etc.). The sector where the senior security executive is hierarchically closest to the CEO is Technology and Telecommunications, followed by Consumer Services, Oil and Energy, and Financial Services.

This study is very much focused on management by the security function, and it is not surprising that those companies that have considered the need, or have been obliged, to set up a specific security function to manage security risks have reached a high degree of maturity of their management system, including resilience. Perhaps, also, because most of them have been operating in volatile and high-risk environments for many years, and the tangible result of the application of the continuous improvement process is already visible. Let us not forget that, within the structure of the management system, “Improvement” has the highest degree of maturity (4.8), the same degree as the result of “Context of the Organisation”. It is at this point between “Improvement” (linked with “Act” according to Deming's cycle) and “Context of the Organisation” (“Plan”) that the Deming cycle restarts.

If we exclude the operations related to the “traditional” security function (5.1 Intelligence operation; 5.2 Information Security Operation; and 5.3 Protection of persons, assets, and information) and keep only the cross-cutting resilience operations (5.4 Incident management; 5.5 Business Continuity; and 5.6 Crisis Management) then we get the isolated result of the resilience management system. In this respect, the resilience management system's performance on its own is very similar to that of the joint security and resilience system. But the operation performance (“DO”) drops slightly in the latter compared to the one integrated with security, with a resilience operation score of 4.1 compared to 4.3 for the one integrated with security. Looking at them separately, there is some difference between Incident Management Operations (4.18) and Business Continuity and Crisis Management (both 4.09). It has been observed during the interviews that the Security department has traditionally been more involved in the coordination of crisis management, and that in some cases, business continuity is outside the scope of the exclusive responsibility of the security function. However, the frequent scenarios affecting technology sometimes focus the development of business continuity plans only on the technological side and on the disaster recovery plans, without taking into account the rest of the critical business processes. Interviews also revealed a lack of unified leadership in a single resilience function (crisis management, business continuity and incident management), reflected in the absence of a specific resilience policy that provides a strategic line of action at the head of a single department, although separately they achieve a high degree of maturity. Concerning crisis management and business continuity operations, it was found that high values in Section "Results of the analysis" of management system support determine a high value in resilience operations. It was also found that the values of the crisis management section are highly dependent on the values of training and awareness, which reinforces the idea that an adequate preparation of the members of the crisis management teams substantially influences the operational capabilities of preparedness, response, and recovery.

Furthermore, if we exclude resilience-related operations and just stick to “traditional” security operations, we observe that their maturity is slightly higher (4.4) compared to the result obtained when we isolate resilience operations (4.1). This is probably because further knowledge is still needed on how OR works and how it can be developed (Duchek, 2019), while specific security operations have been developing for much longer and their implementation has even been boosted recently by a regulation on critical infrastructure that affects most of these companies that provide essential services to society.

Within the security-specific operations, the highest value has been achieved by the intelligence operation, which seems to make sense as business organisations need to reduce uncertainty with respect to risks that may impact their strategic objectives. Intelligence has usually been more focused on “business” intelligence, often supported by market “experts” who have traditionally achieved a better positioning of a product or service. However, it is no longer enough to address financial or market risks, as operational risks (including pandemics or large-scale cyber-attacks) are now at the forefront of the concerns of countries and large business organisations (World Economic Forum, 2023). Spanish multinational companies, like many others, have been forced to look for “blue ocean strategies” outside Spain in order to balance their profit and loss accounts and diversify their investments. This expansion outside traditional areas of Spanish business, such as Europe or Latin America, has brought expansion strategies up against the reality of an environment with little economic stability and political and social instability. Most of the companies surveyed have highly specialised intelligence personnel, trained to filter the enormous amount of information from the environment and then pass on only the information which adds value to strategic business decision-making to senior management.

An assessment was made of whether senior management demonstrates leadership and commitment to the security and resilience management system. This included ensuring that policies are in place that are compatible with the company's strategy, integrating the requirements of this management system into business processes, providing it with all the necessary resources, communicating its importance, achieving the expected results, and encouraging its continuous improvement. It should be noted that in order to achieve this, it is essential to have an approved policy and defined roles, responsibilities, and authority in the organisation. Although the values, in general, have been very high in this section, they are slightly higher in the Financial Services sector, followed by the Oil and Energy sector.

The Planning section takes into account actions to address risks and opportunities, risk assessment and risk treatment, as well as the objectives and planning to achieve them. The results show that this section is slightly higher in the Oil and Energy sector, followed by the Financial Services sector. With regard to risk assessment and risk treatment, it was found that high values in the “Support” section of the management system determine a high value in this risk-related process. This suggests that, if resources with adequate competence and training are available, as well as relevant communication and an appropriate regulatory/documentation framework, this risk assessment and treatment process will be better achieved. Finally, throughout the process's life-cycle, good communication between response team members, committees, and stakeholders is essential to avoid delays, inconsistent execution, and massive failure of mission effectiveness (Goosman, 2022).

Training has had its own section in this study, both in terms of training/awareness of all employees and that of the security department staff. Only 18% of the companies do not have a specific programme for employees or do not have it fully implemented. It is generally provided at the time of any employee's induction, as part of their induction package, and periodically with specific campaigns through internal communication networks or campaigns associated with a specific risk (cybersecurity, information security, fraud, etc.). The same ratios were observed for specific training for security department staff, with slightly higher percentages in the Oil and Energy sector, followed by the Financial Services sector. Training for security department staff includes organisational, operational, technological, and security risk management aspects; however, 64% consider that their organisation does not have all its training needs covered. Some respondents expressed a lack of specific training for personnel who do not hold the position of senior security executive, specifically in middle management and technical positions. For example, specialisation in security project management and implementation; fraud prevention; or corporate investigation. Other respondents refer to training related to artificial intelligence and the use of large data, in relation to security operations. To achieve this, it is necessary to seek training overseas or to have previously acquired experience of this type in other public or private organisations. For 73%, an insufficient budget and the lack of training provisions in Spain are among the reasons why not all security training needs are met. Finally, it is evident from the results that a high value in training and awareness also determines a high value in the operations section.

Conclusion

After exploring the security and organisational resilience model in some of the most significant companies in Spain, a high degree of maturity of the management system has been observed in the selected sample, reaching the “Managed” level and verging on the maturity limit (Optimised), which corroborates the first hypothesis put forward in this type of organisation. In relation to the second hypothesis, the sample of leading Spanish companies — many of which are listed on the stock exchange — shows that they manage their security and resilience through a management system led by a security department in accordance with the country's regulations and the company's needs to meet its strategic objectives in highly uncertain geographic and political environments.

On the other hand, the maturity of the security and resilience management system has been found to be aligned with the organisation's objectives. It is also conditioned by the support of senior management, with very high values observed in general, although the support of senior management is slightly higher in the Financial Services sector, followed by the Oil and Energy sector. This may be because security and resilience are an intrinsic necessity to achieve their strategic objectives, given their volume of operations and geographical dispersion in increasingly uncertain environments.

However, it should be noted that some authors warn that the information obtained may not always reflect reality, as it is obtained through indirect observation, depending on what respondents are willing to report (Sierra Bravo, 2007). Furthermore, a more comprehensive study could determine the actual implementation of the management system through key performance indicators in each of the processes of the management system.

Another limitation was not being able to have all sectors represented in the sample, an issue that should be taken into account in future studies, increasing the number as much as possible and trying to have a proportional number representing each sector.

Overall, there is a high degree of maturity in the security and resilience management system, led by the senior security executive, who does not always report to the top level of the organisation, even though they are professionals of recognised prestige. In addition, there is still an open debate about which function should lead the resilience of an organisation, which could also be led by the corporate risk function, or even through a specific resilience department that encompasses risk governance headed by a CRO (Chief Resilience Officer) (Feist, 2018).

An evolution can be seen in the increasingly broad type of operations developed by the security department, drawing on its capabilities and expertise, such as intelligence and crisis management. There is still room for improvement in developing resilience beyond pure defence (Deloitte, 2022), and this is where intelligence capabilities could be of great use (Kerr, 2016; Miidom et al., 2022).

Training has proven to be a key element in the implementation of the security strategy. However, there are shortcomings in both the offer and the involvement of the entire organisation, being more advanced in those sectors which, due to regulatory requirements or expansion needs in high-risk areas, have been forced to do so, such as critical entities. The training of the rest of the corporate security department team is not yet defined by the Spanish regulator, especially in terms of OR.

Notably, organisations in countries where some of their infrastructure has been identified as “critical” may have some advantage if they have already included all or some of the resilience governance activities among the security department's functions, given that some regulations, such as the European one, have already replaced the term “protection” with “resilience”, and the term “infrastructure” with “entities” (European Union, 2022). This goes from the concept of “Protection of Critical Infrastructures” to the concept of “Critical Entities Resilience” (Pursiainen & Kytömaa, 2022).

Derived from this model and its application, which favours a “get down to business” approach to the processes that enable effective implementation of resilience, other lines of research open up at the strategic level to explore the implications of organisations' boards and steering committees in risk management and their influence on OR governance, including on the potential of OR governance in new entrepreneurship projects and much smaller organisations operating in highly uncertain and volatile environments. From an operational point of view, it will be interesting to delve deeper into other areas that have been part of this study, such as intelligence, as this is a key element to go beyond the merely reactive concept of resilience.

References

Annarelli, A., & Nonino, F. (2016). Strategic and operational management of organizational resilience: Current state of research and future directions. Omega (oxford), 62, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omega.2015.08.004

ANSI/ASIS. (2017). ANSI/ASIS ORM.1–2017 Security and Resilience in Organizations and their Supply Chains. Retrieved Apr 11, 2022, from https://www.asisonline.org/publications--resources/standards--guidelines/orm/

Arena, M., Azzone, G., Cagno, E., Silvestri, A., & Trucco, P. (2014). A model for operationalizing ERM in project-based operations through dynamic capabilities. International Journal of Energy Sector Management, 8(2), 178–197. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJESM-09-2012-0008

ASIS. (2021). Business Continuity Management Guideline (ASIS BCM-2021) - eBook. Retrieved Feb 25, 2023, from https://store.asisonline.org/business-continuity-management-guideline-asis-bcm-2021-ebook.html

Aven, T. (2017). How some types of risk assessments can support resilience analysis and management. Reliability Engineering & System Safety, 167, 536–543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ress.2017.07.005

Bank of England. (2021). Operational resilience of the financial sector. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/financial-stability/operational-resilience-of-the-financial-sector

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. (2021). Revisions to the principles for the sound management of operational risk. https://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d515.pdf

BME. (2022a). IBEX 35. Retrieved Feb 21, 2022, from https://www.bolsasymercados.es/bme-exchange/en/Indices/Ibex

BME. (2022b). List of Companies by Sector. Retrieved May 29, 2022, from https://www.bolsamadrid.es/ing/aspx/Empresas/EmpresasPorSectores.aspx

Brooks, D., & Braes, B. (2011). Organisational Resilience: Understanding and identifying the essential concepts. https://doi.org/10.2495/SAFE110111

BSI. (2014). BS 65000:2014 Guidance on organizational resilience. Retrieved Mar 15, 2022, from https://www.bsigroup.com/en-GB/our-services/Organizational-Resilience/#:~:text=Organizational%20resilience%20is%20defined%20by,order%20to%20survive%20and%20prosper%22

Casas Anguita, J., Repullo Labrador, J. R., & Donado Campos, J. (2003a). La encuesta como técnica de investigación. Elaboración de cuestionarios y tratamiento estadístico de los datos (II). Atención Primaria, 31(9), 592–600. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0212-6567(03)79222-1

Casas Anguita, J., Repullo Labrador, J. R., & Donado Campos, J. (2003b). La encuesta como técnica de investigación. Elaboración de cuestionarios y tratamiento estadístico de los datos (I). Atención Primaria, 31(8), 527–538. https://doi.org/10.1157/13047738

Central Bank of Ireland. (2021). Cross Industry Guidance on Operational Resilience. https://www.centralbank.ie/docs/default-source/publications/consultation-papers/cp140/cross-industry-guidance-on-operational-resilience.pdf

CMMI Institute. (2020). Capability Maturity Model Integration. https://cmmiinstitute.com/cmmi

CNPIC. (2021). Planning for the Protection of Critical Infrastructures. Retrieved Oct 14, 2019, from https://cnpic.interior.gob.es/opencms/es/detail-page/articulo/La-Comision-Nacional-para-la-Proteccion-de-Infraestructuras-Criticas-aprueba-el-P.E.A

Commonwealth of Australia. (2016). Organisational Resilience - Good Business Guide. Retrieved Apr 29, 2022, from https://www.organisationalresilience.gov.au/Documents/Organisational-Resilience-Good-Business-Guide.PDF

Cooper, T., & Faseruk, A. (2011). Strategic risk, risk perception and risk behaviour : Meta-analysis. Journal of Financial Management and Analysis, 24(2), 20–29.

COSO. (2017). ERM – Integrating with strategy. Retrieved Feb 23, 2022, from https://www.coso.org

Deloitte. (2022). Toward True Organizational Resilience. Retrieved Nov 12, 2022, from https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/us/Documents/01_Global_Resilience_report_October_2022_wc.pdf

Duchek, S. (2019). Organizational resilience: a capability-based conceptualization. Business Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40685-019-0085-7

European Union. (2022). Directive (EU) 2022/2557 the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2022 on the Resilience of Critical Entities and Repealing Council Directive 2008/114/EC. https://www.europeansources.info/record/proposal-for-a-directive-on-the-resilience-of-critical-entities/

Falasca, M., Zobel, C. W., & Cook, D. (2008). A decision support framework to assess supply chain resilience. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 5th International ISCRAM Conference, 596–605.

Federal Reserve Board. (2020). Agencies release paper on operational resilience. https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/bcreg20201030a.htm

Feist, T. (2018). A Growing Focus on Resilience. Journal of Property Management, 83(5), 20–22.

FERMA. (2021). The role of risk management in corporate resilience. https://www.ferma.eu/publication/the-role-of-risk-management-in-corporate-resilience/

Gates, S. (2006). Incorporating Strategic Risk into Enterprise Risk Management: A Survey of Current Corporate Practice. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 18(4), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6622.2006.00114.x

Gibson, C. A., & Tarrant, M. (2010). A “conceptual models” approach to organisational resilience. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, 25(2), 8–14.

Goosman, A. (2022). Evolving corporate crisis response coordination for maximum resilience. Journal of Business Continuity & Emergency Planning, 15(3), 237–244.

Gracey, A. (2020). Building an organisational resilience maturity framework. Journal of Business Continuity & Emergency Planning, 13(4), 313–327.

Hepfer, M., & Lawrence, T. B. (2022). The heterogeneity of organizational resilience: Exploring functional, operational and strategic resilience. Organization Theory, 3(1), 26317877221074700.

Hillmann, J., & Guenther, E. (2021a). Organizational Resilience: A Valuable Construct for Management Research? International Journal of Management Reviews : IJMR, 23(1), 7–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12239

Hillmann, J., & Guenther, E. (2021b). Organizational Resilience: A Valuable Construct for Management Research? International Journal of Management Reviews, 23(1), 7–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12239

ISO. (2017). ISO 22316:2017. Security and resilience – Organizational resilience – Principles and attributes. Retrieved Feb 8, 2022, from: https://www.iso.org/standard/50053.html

Kerr, H. (2016). Organizational resilience. Quality, 55(7), 40–43.

Leo, M. (2020). Operational resilience disclosures by banks: Analysis of annual reports. Risks (basel), 8(4), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks8040128

León, O. G., & Montero, I. (1993). Diseño de investigaciones : Introducción a la lógica de la investigación en psicología y educación. McGraw-Hill.

López-Roldán, P., & Fachelli, S. (2015). Metodología de la investigación social cuantitativa. Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

Ludbey, C. R., Brooks, D. J., & Coole, M. P. (2018). Corporate Security: Identifying and Understanding the Levels of Security Work in an Organisation. Asian Journal of Criminology, 13(2), 109–128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-017-9261-x

Marquez-Tejon, J., Jimenez-Partearroyo, M., & Benito-Osorio, D. (2022). Security as a key contributor to organisational resilience: A bibliometric analysis of enterprise security risk management. Security Journal, 35(2), 600–627. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41284-021-00292-4

Marquez-Tejon, J., Jimenez-Partearroyo, M., & Benito-Osorio, D. (2023). Integrated security management model: A proposal applied to organisational resilience. Security Journal. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41284-023-00381-6

McManus, S. T. (2008). Organisational resilience in New Zealand. http://hdl.handle.net/10092/1574

Medianero Burga, D. (2014). Metodología de Estudios de Línea de Base. Pensamiento Crítico. https://doi.org/10.15381/pc.v15i0.8994

Ministerio de Justicia e Interior. (2008). Article 96. Private Security Regulation. Assumptions of mandatory existence of the security department. Retrieved sep 5, 2020, from https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-1995-608&b=149&tn=1&p=20080112#a96

Miidom, D. F., Okoroafor, C. E. A., & Mabel, U. I. (2022). ORGANIZATIONAL INTELLIGENCE AND CORPORATE RESILIENCE. International Journal of Advanced Academic Researc, 8(3), 53–71.

Milkau, U. (2021). Operational resilience as a new concept and extension of operational risk management. Journal of Risk Management in Financial Institutions, 14(4), 408–425.

Ogrean, C. (2018). INTEGRATING RESILIENCE AND SUSTAINABILITY INTO THE CORE ORGANIZATIONAL STRATEGY – IS IT POSSIBLE OR IMPERATIVE? Economic and Social Development: Book of Proceedings, 526–536.

Omorede, A. (2021). Managing crisis: A qualitative lens on the aftermath of entrepreneurial failure. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 17(3), 1441–1468. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-020-00655-0

Palacios Bascón, I., & Rodríguez Muñoz, Y. (2020). La bolsa de valores. El diario de un inversor medio.

Pursiainen, C., & Kytömaa, E. (2022). From European critical infrastructure protection to the resilience of European critical entities: what does it mean? Sustainable and Resilient Infrastructure. https://doi.org/10.1080/23789689.2022.2128562

Rosemann, M., & De Bruin, T. (2005). Towards a business process management maturity model. Paper presented at the ECIS 2005 Proceedings of the Thirteenth European Conference on Information Systems, 1–12.

Santesmases Mestre, M. (2009). Dyane versión 4: Diseño y análisis de encuestas en investigación social y de mercados / Miguel Santesmases Mestre. Pirámide.

Saunders, W. S. A., & Becker, J. S. (2015). A discussion of resilience and sustainability: Land use planning recovery from the Canterbury earthquake sequence, New Zealand. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 14, 73–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2015.01.013

Settembre-Blundo, D., González-Sánchez, R., Medina-Salgado, S., & García-Muiña, F. E. (2021). Flexibility and Resilience in Corporate Decision Making: A New Sustainability-Based Risk Management System in Uncertain Times. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 22, 107–132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40171-021-00277-7

Siambabala, B. M., O’Brien, G., O’Keefe, P., & Rose, J. (2011). Disaster resilience: A bounce back or bounce forward ability? Local Environment, 16(5), 417–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2011.583049

Sierra Bravo, R. (2007). Técnicas de investigación social : teoría y ejercicios / Restituto Sierra Bravo (14ª ed. 4ª reimp. ed.). Madrid : Paraninfo.

Skare, M., & Porada-Rochon, M. (2021). Measuring the impact of financial cycles on family firms: How to prepare for crisis? International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 17(3), 1111–1130. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-020-00722-6

Slagmulder, R. (2022). Organizational resilience:a review of the literature, with lessons learned from a corporate governance and SME perspective. Retrieved May 2, 2023, from https://www.guberna.be/en/know/organizational-resilience-review-literature-lessons-learned-corporate-governance-and-sme

Stephenson, A. V. (2010). Benchmarking the resilience of organisations.

Thompson, M. A., Ryan, M. J., Slay, J., & McLucas, A. C. (2016). A New Resilience Taxonomy. INCOSE International Symposium, 26(1), 1318–1330. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2334-5837.2016.00229.x

Trucco, P., & Petrenj, B. (2017). Resilience of Critical Infrastructures: Benefits and Challenges from Emerging Practices and Programmes at Local Level. (pp. 225–286). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-1123-2_8

Will, M., Bertrand, J., & Fransoo, J. C. (2002). Operations management research methodologies using quantitative modeling. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 22(2), 241–264. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443570210414338

World Economic Forum. (2023). The Global Risks Report 2023. Retrieved Mar 23, 2022, from https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Global_Risks_Report_2023.pdf?_gl=1*onufhj*_up*MQ..&gclid=CjwKCAjwgqejBhBAEiwAuWHioNs2Hlk1L2TOE4mzUU7Lw1xUQ2TMifuWBqGr0rV2tK_rslx66jAuPhoCAsYQAvD_BwE

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Marquez-Tejon, J., Jimenez-Partearroyo, M. & Benito-Osorio, D. Organisational resilience management model: a case study of joint stock companies operating in Spain. Int Entrep Manag J (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-024-00967-5

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-024-00967-5