Abstract

Over the years, academic attention towards work-family conflict (WFC) issues has been constantly growing due to the socio-economic changes occurring in society. In line with this, great effort has been devoted to investigating WFC experienced by employees, while still almost untapped is the conversation with reference to women entrepreneurs. Moreover, the few studies that deal with women entrepreneurs’ WFC have mainly analysed its negative consequences rather than its predictors. Thus, this study aims to fill such research gap by analysing women entrepreneurs’ WFC antecedents. Based on the bidimensional conceptualization of WFC, distinguishing between work interference with family (WIF) and family interference with work (FIW), this study verifies an expanded model of the WFC which takes into consideration either the within-domain effects or the cross-domain effects of work and family stressors on WIF and FIW experienced by women entrepreneurs. In doing so, an analysis based on data from 669 women entrepreneurs has been conducted. Results show that both within-domain relationships and cross-domain relationships play a key role in explaining the WFC experienced by women entrepreneurs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

People’s attempts to balance the different features of their work with their family demands have been traditionally investigated through the lens of role theory (Biddle 1986, p. 67). This theory is mainly based on the scarcity hypothesis (e.g. Marks 1977), implying that people can benefit from a limited (and fixed) amount of both time and energy; consequently, the more role demands increase, the higher the role conflict faced by individuals. Within this framework, the concept of work-family conflict (WFC) stands out, traditionally defined as “a form of inter-role conflict in which the role pressures from the work and family domains are mutually incompatible in some respect” (Greenhaus and Beutell 1985, p. 77).

Recently, academic attention towards WFC has notably increased. Today, more couples than in the past are engaged in dual-earner relationships. This means that not only do both partners have work responsibilities, but they also share family demands and, thus, are likely to face the stressful task of coordinating their work and family roles (e.g. Friedman and Greenhaus 2000). Accordingly, research has investigated both the antecedents and consequences of WFC, mainly focusing the analysis on employees’ WFC experience.

Surprisingly, still almost untapped is the conversation on WFC issues in relation to entrepreneurs (Jennings and McDougald 2007). A general justification for such scant attention paid to entrepreneurs’ WFC can be related to the widespread theoretical assumption that being an entrepreneur would imply benefiting from greater freedom and flexibility than employees, allowing the former to better balance work and family demands. In reality, as well explained by Parasuraman et al. (1996), the depicted freedom is “bounded by their responsibility for the survival and economic success of the enterprise” (p. 277); heavy work responsibilities reduce the entrepreneur’s ability to devote time and energy to the family, contributing to the manifestation of WFC. Consequently, being entrepreneurs generates not only benefits, but also significant costs, especially in terms of both professional and personal pressures and constraints, if compared to that experienced by traditional organizational employees.

Even more surprising is the still scarce attention towards this topic with specific regard to women entrepreneurs (Poggesi et al. 2016) this literature gap is unexpected because it has been largely demonstrated that women have a tendency to experience higher levels of WFC compared to men (Duxbury and Higgins 2001; Fahlén 2014; Lee et al. 2014; McGinnity and Calvert 2009) and because this tendency is exacerbated when referring to women entrepreneurs, as already verified by Loscocco et al. 1991. Women entrepreneurs, as working women and often partners/mothers, undertake multiple roles in the family and in the business. This triggers conflicts as they must maintain a simultaneously dual presence at home and at work: on the one hand, as women, they are still the primary nurturers and care givers in the family (Sullivan and Meek 2012); on the other, as entrepreneurs, they are in charge of the survival and success of their firms as well as of the welfare of their employees.

Nevertheless, some theoretical and empirical papers have been settling the ground (e.g. Jennings and Brush 2013; Jennings and McDougald 2007; Shelton 2006), even if the academic literature is still facing paucity in terms of empirical evidence on the constructs and mechanisms of WFC experienced by women entrepreneurs. In particular, the few studies that deal with this specific topic have mainly focused their attention on the consequences of WFC for women entrepreneurs rather than on its antecedents. According to the literature, WFC can negatively affect: i) the size and performance of the firms (Forson 2013; Jennings and McDougald 2007; Loscocco and Bird 2012; Rehman and Azam Roomi 2012; Stoner et al. 1990); ii) the well-being of the entrepreneur (Shelton 2006); and iii) woman’s satisfaction with her job, marriage, and life (Lee Siew Kim and Seow Ling 2001).

However, given that women own about 46% of all the businesses in the world (GEM 2017), understanding the antecedents of women entrepreneurs’ WFC and their mechanism seems to be particularly relevant for helping women, but also policy makers, to identify more targeted actions to reduce the strain of WFC and thus reduce the negative highlighted consequences. This study aims to fill this gap by investigating the antecedents of WFC experienced by women entrepreneurs, and analysing data from 669 women entrepreneurs operating in Italy.

In particular, this paper is among the very few studies that a) in line with research on employees’ WFC, separately analyses the WFC as articulated in two constructs: work-to-family conflict (WIF) and family-to-work conflict (FIW) (e.g. Gutek et al. 1991; Zhang et al. 2012; Tews et al. 2016); and b) examines the most frequently investigated family domain and work domain stressors in order to understand if and to what extent they actually can be considered as the antecedents of WFC experienced by women entrepreneurs, presenting arguments for both the within and cross-domain effects of work and family stressors on WIF and FIW.

The paper is organized as follows: an updated literature review is first presented; the methodology of the empirical analysis and the results are then illustrated; finally, the implications of the findings as well as the limitations of the study are discussed and directions for further research are suggested.

Literature review

The premise of this study is that the family and business domains are closely interrelated (Aldrich and Cliff 2003) and that overtaking – or at least trying to properly manage – the eventual conflicts between family and work is a key goal not only for employees, but also for entrepreneurs in all stages of the firm’s life cycle.

Work-family conflict

In the rich work-family research, the conflict perspective has dominated over recent years. This perspective is based on the scarcity hypothesis: because of individuals’ limited resources (e.g. of time, attention, energy) “participation in the work (family) role is made more difficult by virtue of participation in the family (work) role” (Greenhaus and Beutell 1985, p. 77). When role pressures from the work and/or family domain are intensified, they can somehow be mutually incompatible, thus being the cause of WFC (Greenhaus and Beutell 1985).

Originally, WFC was theorized as a unidimensional construct (e.g. Bohen and Viveros-Long 1981; Holahan and Gilbert 1979), meaning that the influence of work on family and the influence of family on work were not considered to be separate. Stemming from the milestone paper by Greenhaus and Beutell (1985), it is only with Gutek et al. (1991) and Frone et al. (1992a) that WFC is empirically conceptualized as a construct generated by two bidirectional effects: (a) work-family conflict (WIF), occurring when work interferes with family life, and (b) family-work conflict (FIW), occurring when family life interferes with work (Netemeyer et al. 1996). This bidimensional conceptualization of WFC, based on considering WIF and FIW as two related but distinct constructs (e.g. Bellavia and Frone 2005; Ford et al. 2007; Grzywacz et al. 2002; Hill 2005; Kossek and Ozeki 1998; Mesmer-Magnus and Viswesvaran 2005), has been largely adopted over the last 20 years, especially for the investigation of employees’ experience. During these years, researchers have, in particular, focused their attention on the antecedents and consequences associated with each of the two constructs.

Regarding the antecedents, factors related to an individual’s job (i.e. work domain stressors) have been traditionally considered to be antecedents of WIF, while factors related to individuals’ family and non-work life (i.e. family domain stressors) are generally classified as antecedents of FIW. These relationships have been labelled within-domain relationships and have received strong empirical support over the years (e.g. Frone et al. 1992a, b, 1997; Greenhaus and Beutell 1985; Kinnunen and Mauno 1998). However, recently, as underlined by Greenhaus and Allen (2011), the asymmetry of the domain effect has emerged in meta-analyses (e.g. Byron 2005; Mesmer-Magnus and Viswesvaran 2005, and even more recently Michel et al. 2011) but also in several papers (e.g. Hargis et al. 2011), thus contributing to bring to light the so-called “cross-domain effect”. Its rationale lies in the idea that when the demand of one role is too relevant, other resources from other roles can be used.

With regard to the consequences, two different perspectives exist, i.e. the cross-domain hypothesis and the matching hypothesis. The former states that the conflict originates in one domain and affects the other (i.e. WIF on family related outcomes) (e.g. Frone et al. 1992a, b, 1997). The latter hypothesis points out that the effect is stronger in the same domain as the stressors (i.e. FIW on family related outcomes) (e.g. Moore 2000). Although the former has dominated the work-family literature, also receiving strong empirical support (e.g. Bellavia and Frone 2005; Frone 2003; Frone et al. 1992a, b, 1997), the most recent meta-analyses clearly support the matching hypothesis (e.g. Amstad et al. 2011; Nohe et al. 2015; Shockley and Singla 2011), thus opening up a new debate.

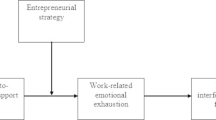

In this study, we focus our attention on the WFC antecedents experienced by women entrepreneurs, verifying both the within- and cross-domain effects of work/family stressors on WIF and FIW. Typically, antecedents are mostly classified in work and non-work variables (e.g. Byron 2005; Michel et al. 2011) and the specific antecedents selected in this paper were chosen as they are those most frequently included both in reviews of WFC antecedents (Byron 2005; Ford et al. 2007; Michel et al. 2011) and in WFC models (e.g. Michel and Clark 2009).

Work domain stressors

In the work-family research domain, a plethora of studies regarding the work antecedents of WFC have been published and, stemming from the paper by Greenhaus and Beutell (1985), variables such as job involvement, time spent at work, and flexibility have been predominantly analysed. In this paper, competing arguments for the within- and cross-domain effects of work stressors on WIF and FIW experienced by women entrepreneurs are presented.

First, regarding job involvement, this refers to “the importance of work to the individual, and to his or her psychological involvement in the work role” (Parasuraman and Simmers 2001). It is generally conceptualized as an antecedent of WIF, because high levels of emotional involvement at work may cause difficulties in the competing role within the family, due to limited energy resources, both psychological and physical (Adams et al. 1996; Frone et al. 1992a; Greenhaus and Parasuraman 1999). In line with this, the meta-analysis developed by Byron (2005) shows that employees with higher job involvement have more WIF than FIW. Similar results have been verified more recently by Michel et al. (2011), suggesting that as job involvement increases, WIF also increases.

However, regarding the entrepreneurship literature, Parasuraman et al. (1996) find that job involvement is not significantly related to WIF, neither for men nor women entrepreneurs, but is positively related to FIW in both cases, thus supporting the cross-domain effects. Moreover, Parasuraman and Simmers (2001) verify that job involvement is not related to WFC in the case of entrepreneurs, while it is in the case of employees.

Accordingly, we hypothesize:

-

Hp 1.a: Increased job involvement is positively related to WIF experienced by women entrepreneurs.

-

Hp 1.b: Increased job involvement is positively related to FIW experienced by women entrepreneurs.

Second, regarding the time committed to work, as suggested by Kelly et al. (2011), this is perhaps the most consistent predictor of WIF (e.g. Batt and Valcour 2003; Berg et al. 2004; Voydanoff 2004). Results from the literature seem to be unequivocal: longer working hours are linked to higher levels of WIF, as the greater the amount of time devoted to work, the lower the amount of time available for the family (e.g. Carlson and Perrewe 1999; Greenhaus et al. 1987; Jacobs and Gerson 2004; Nielson et al. 2001; Valcour 2007). In the employment literature, some papers are worth noting: Pocock et al. (2007), for example, show that employees working more than 60 h per week experience the highest level of WIF, followed by those who work between 45 to 60 h per week and then by the groups working fewer hours; Kinnunen et al. (2006) verify that working more than 45 h per week increases WIF both for men and women.

Although the within-domain hypothesis is the one most frequently proposed, several studies have also hypothesized the cross-domain hypothesis (e.g. Luk and Shaffer 2005) and others have verified an unexpected positive relationship between time committed to work and FIW (e.g. Lingard et al. 2012). A possible explanation is that as work time demands increase, family has more opportunities to intrude on this domain: with less time at home, employees could indeed experience depletions of their family resources, thus increasing FIW.

In the entrepreneurship literature, the only two papers that empirically analyse the relationship between time committed to work and WFC show, respectively, that this variable is positively related to WIF (Parasuraman et al. 1996) and that hours spent at work increase WFC more for entrepreneurs than for employees (Parasuraman and Simmers 2001), thus confirming the widespread viewpoint that being involved in one’s own business may often represent a burden rather than a balance-facilitating instrument.

Accordingly, we hypothesize:

-

Hp 1.c: Time committed to work is positively related to WIF experienced by women entrepreneurs.

-

Hp 1.d: Time committed to work is positively related to FIW experienced by women entrepreneurs.

Third, flexibility refers to flexible work arrangements defined as “alternative work options that allow work to be accomplished outside of the traditional temporal and/or spatial boundaries of a standard workday” (Shockley and Allen 2007, p. 480).

Regarding the relationship between flexibility and WFC, results are still mixed. Earlier research shows that employees with schedule flexibility experience low levels of WIF (e.g. Anderson et al. 2002; Frone and Yardley 1996; Kinman and Jones 2008; Kossek et al. 2006). Such results can be justified by the fact that, when flexibility increases, the control over work situations increases too and, consequently, the severity of WIF decreases (Greenhaus and Kopelman 1981). However, recently, no relationship between the two has been tested (e.g. Hammer et al. 2005; Lapierre and Allen 2006; Mesmer-Magnus and Viswesvaran 2005; Schieman et al. 2009) while Byron (2005) finds a negative relationship between flexibility and both WIF and FIW; even more recently, Beutell et al. (2014) have verified that for non-Hispanic employees (both women and men) flexibility is negatively related both to WIF and FIW.

In the entrepreneurship literature, flexibility is an investigated topic, as it has been shown to be a motivator for self-employment (e.g. Kirkwood and Tootell 2008; Loscocco 1997). Therefore, women entrepreneurship research has been generally focused on why women become self-employed and has generally ignored if and how flexibility can really help them to overcome WFC. The few studies that investigate such a relationship yield mixed results. On the one hand, some papers point out that flexibility is negatively related to WFC (e.g. McNall et al. 2010). This result can be explained by considering that flexibility allows entrepreneurs to structure their work in a way that matches their family responsibilities, thus minimizing or reducing WFC. On the other hand, Parasuraman et al. (1996) and Parasuraman and Simmers (2001) respectively verify that schedule inflexibility is not significantly related either to WIF or to FIW and that flexibility is not negatively related to WFC. Such results can be explained by considering that the relevance of flexibility is stronger for those women who are breadwinners and are also responsible for the survival of their firm (e.g. Annink and den Dulk 2012). Kirkwood and Tootell (2008) conclude that while flexibility appears to be a clear example of a desired outcome deriving from being an entrepreneur, the empirical evidence suggests that, especially in the case of women entrepreneurs, flexibility may be somewhat of a myth.

Accordingly, we hypothesize:

-

Hp 1.e: Flexibility is negatively related to WIF experienced by women entrepreneurs.

-

Hp 1.f: Flexibility is negatively related to FIW experienced by women entrepreneurs.

Family domain stressors

The most relevant family variables analysed today by scholars are still the variables taken into account by Greenhaus and Beutell (1985), i.e. family involvement, parental demands and time committed to family. As for the work domain variables, both the within-domain and the cross-domain effects of family stressors on WIF and FIW experienced by women entrepreneurs are hypothesized.

First, regarding family involvement, this variable refers to the importance that individuals attribute to the family and the related psychological investment they put into their family. These pressures can be related to aspects such as the high amount of time needed to respond to family demands or high levels of mental or physical energy required, according to the family’s circumstances and the individual’s role within the family (e.g. Edwards and Rothbard 2000; Hargis et al. 2011).

Scholars do argue about the fact that high requirements from the family side are very likely to generate, as a consequence, a limitation in resources available to be invested (both at the physical and mental levels) in the work domain, thus are likely to highly interfere with work. Accordingly, over the years, scholars have reported family involvement to be positively related to FIW (see, as examples, Adams et al. 1996; Frone et al. 1992a), thus suggesting that family involvement represents an important antecedent of FIW. However, more recently the employees’ literature (e.g. Boyar and Mosley 2007; Hargis et al. 2011) and Byron’s (2005) and Michel et al.’s (2011) meta-analyses have verified the cross-domain effects of family involvement on WFC. Hargis et al. (2011) (p. 402), as an example, find that family involvement is an important positive predictor of WIF but it is not identified as an important predictor of FIW.

In the entrepreneurship literature, scholars to date agree on considering the high salience of family, depending on high family needs and responsibilities, as a possible limitation for women entrepreneurs in devoting a suitable amount of energy to their firm (e.g. Noor 2004; Winn 2005). However, Parasuraman et al. (1996) find that a high level of family involvement is associated with decreased WIF, while it is not associated with FIW.

Accordingly, we hypothesize:

-

Hp 2.a: Increased family involvement is positively associated with FIW experienced by women entrepreneurs.

-

Hp 2.b: Increased family involvement is positively associated with WIF experienced by women entrepreneurs.

Second, regarding parental demand, this refers both to the number of children of working parents and to children’s ages; scholars argue that parental demand is an element able to significantly affect FIW (e.g. Bakker et al. 2008; Dilworth 2004; Grzywacz and Marks 2000; Lee Siew Kim and Seow Ling 2001). This interference increases when the number of children increases and strictly depends on their ages. The interference is particularly strong for those parents with infants and pre-school children; it reduces with school age children and reaches a minimum level in the case of working parents with adult children (especially those with children no longer living at home). This happens because younger children tend to require more care and resources than older children (e.g. Beigi et al. 2012; Fu and Shaffer 2001; Hargis et al. 2011). Thus, parents with infant and/or pre-school children generally devote less time and less physical and psychological energy to work, scoring higher levels of FIW (e.g. Vieira et al. 2016). However, from Michel et al.’s (2011) review, it emerges that both parental demands (number and age of children) and number of children have small relationships with FIW. Moreover, Byron (2005) declares that “nonwork domain variables that have been referred to as family demands (i.e., number of children, age of youngest child, …) were nearly as related to FIW as to WIF” (p.191). In this vein, Frone and Yardley’s (1996) and results show that parental demand is a predictor of both FIW and WIF.

In the entrepreneurship literature, scholars devote particular attention to the role of parental demands but the papers that empirically link such variable to WFC are still scant. Overall, the literature agrees on the fact that women entrepreneurs with pre-school children tend to be generally dissatisfied with the time they are able to devote to their ventures (e.g. Robichaud et al. 2007). However, according to Parasuraman et al.’s (1996) results, parental demand is unrelated to FIW while it is positively associated with WIF.

Accordingly, we hypothesize:

-

Hp 2.c: Parental demand is positively associated with FIW experienced by women entrepreneurs.

-

Hp 2.d: Parental demand is positively associated with WIF experienced by women entrepreneurs.

Third, regarding time committed to family, the relevance of this variable is related to the fact that the time an individual devotes to family can be considered as a valuable indicator of overall family role demands (e.g. Parasuraman and Simmers 2001). According to the within-domain hypothesis, the amount of time consumed in one domain (family) limits an individual’s ability to fruitfully take part in the activities of the other domain (work) (Ng et al. 2016). In particular, when the time required by family needs is significantly high, the individual would experience greater difficulties in maintaining a significant amount of time available to be dedicated to the work domain. Indeed, scholars argue that the more time is spent on family the more FIW is experienced (e.g. Calvo-Salguero et al. 2012; Lu et al. 2006; Byron 2005; Michel et al. 2011).

However, although the within-domain hypothesis is the most frequently proposed one, a cross-domain hypothesis has been proposed in several studies (e.g. Luk and Shaffer 2005). The rationale is grounded on the idea that as family demands increase, work has more opportunities to intrude in this domain: with less time at work, employees could indeed experience depletions of their work resources, thus increasing WIF. Despite that, no significant relationships were found between time committed to family and WIF (e.g. Luk and Shaffer 2005).

Also in the entrepreneurship literature scholars consider the time devoted by women entrepreneurs to satisfy family needs as a limitation in devoting a sufficient amount of time to their firm (e.g. Robichaud et al. 2007; Winn 2005). However, in this research field, the only paper that analyses the link between time committed to work and WFC is Parasuraman et al.’s (1996) one, whose results differ from those hypothesized in the employment literature as they verify that time commitment to family is negatively related to WIF and is not related to FIW.

Given this evidence, we hypothesize:

-

Hp 2.e: Time commitment to family is positively associated with FIW experienced by women entrepreneurs.

-

Hp 2.f: Time commitment to family is positively associated with WIF experienced by women entrepreneurs.

Social support

Social support is defined as “instrumental aid, emotional concern, informational, and appraisal functions of others in the work (family) domain that are intended to enhance the wellbeing of the recipient” (Michel et al. 2011, p. 92).

With a specific focus on employees, social support in the work domain refers to the help from co-workers, the supervisor, and the organization which aim to improve the welfare of employees (House 1981; Matsui et al. 1995; Kossek et al. 2011). Social support in the non-work domain refers mainly to the support provided by family, spouse/partner and peers (Anatan 2013; Kossek et al. 2011).

In the employees’ literature, the role of social support has been widely investigated and, according to Viswesvaran et al.’s (1999) and Kossek et al.’s (2011) meta-analyses, social support can lower the experienced conflicts or buffer the relationships between work/family demands and WFC.

Particularly focusing on the moderating role of social supports, previous employees’ studies (e.g. Adams et al. 1996; Aryee et al. 1999; Thomas and Ganster 1995; Chang et al. 2014) have conceptualized social supports as moderators that play a stress-buffering role in within-domain relationships. Such a perspective is based on the idea that social supports can buffer the negative effects of work and family stressors on WFC because whoever receives high levels of support can better cope with such conflicts (e.g. Lawrence 2006; Teo et al. 2013).

Regarding the women entrepreneurship literature, the topic is still scarcely investigated (e.g. Chrisman et al. 2005; Nguyen and Sawang 2016). On the one hand, women entrepreneurs do not have the opportunity to benefit from the support that employees may have in the work domain. For this reason, social supports in the work domain can be related, for women entrepreneurs, to people from a business network or to business mentors (Hampton et al. 2009; Jennings and Brush 2013). Indeed, having a supportive working network can contribute, thanks to technical (e.g. sharing of know-how, practices) and/or emotional support (e.g. listening and advising), to alleviating the impact of work stressors on WIF. On the other hand, in the family domain, women entrepreneurs can refer to the same supports available for employees. Family members (e.g. Powell and Eddleston 2013), partners (e.g. Chrisman et al. 2005) and private/public services can provide women entrepreneurs with instrumental support (e.g. help with house tasks or children) and/or emotional support (e.g. listening or caring) that can mitigate the impact of family stressors on FIW.

Accordingly, we hypothesize:

-

Hp 3.a: Networking support moderates the effects of work demand stressors on WIF such that the relationships are weakened.

-

Hp 3.b: Partner support moderates the relationship between family stressors and FIW such that the relationships are weakened.

-

Hp 3.c: Family support moderates the relationship between family stressors and FIW such that the relationships are weakened.

-

Hp 3.d: Private/public services moderate the relationship between family stressors and FIW such that the relationships are weakened.

The overall proposed theoretical framework is presented in Fig. 1.

Methodology

Data collection and sample

The aim of this study is to investigate WFC antecedents in the case of women entrepreneurs. In order to be a suitable target for this analysis, the surveyed women had to meet the following criteria: i) they had to hold at least 51% of the firm’s ownership; ii) they had to be actively involved in the business, by managing the daily business activities; and iii) at least one person had to be employed in the firm.

In accordance with this goal, a survey based on 35 multiple choice answers was mailed to 2300 women entrepreneurs associated with one of the most important women entrepreneurship associations located in Italy. Of the 2300 surveys distributed, 721 responses were obtained, resulting in a 31.35% response rate. After excluding some questionnaires that contained errors or missing values, a final number of 669 usable responses met our criteria.

Although we acknowledge the single source bias (Baugh et al. 2006; Mitchell 1985; Podsakoff and Organ 1986), the link with this association allowed us to reach a high number of women entrepreneurs.

Research variables

Stemming from the milestone studies on WFC (Frone et al. 1992a, 1992b; Greenhaus et al. 1989; Gutek et al. 1991; Parasuraman and Simmers 2001) and from the most updated meta-analyses on the topic (Byron 2005; Ford et al. 2007; Michel et al. 2011), the following variables and measures have been employed in this paper.

Work-family conflicts

According to Gutek et al. (1991), WFC was measured with two Likert-type scales, rated from “1 = strongly disagree” to “6 = strongly agree”.

Four items measure WIF. An illustrative item is “After work, I come home too tired to do some of the things I’d like to do”. These four items were averaged in order to measure WIF. The alpha coefficient was 0.843.

Another four items were used to assess FIW. An illustrative item is “I’m often too tired at work because of the things I have to do at home”. These four items were averaged in order to measure FIW. The alpha coefficient was 0.842.

Work characteristics

Three different variables have been used to analyse work characteristics.

Job involvement

Following Frone et al. (1992a, 1992b), who cite Kanungo (1982a, 1982b), job involvement was measured by four six-point Likert-type items, rated from “1 = strongly disagree” to “6 = strongly agree”. An illustrative item is “Most of my interests are centred around my work”. The alpha coefficient was 0.702.

Time committed to work

This was measured by a self-reporting, behaviourally anchored item that asked respondents: “How many hours per week do you spend working in your company?” The response categories included six levels ranging from (l) Less than 30 h to (6) More than 70 h.

Flexibility

Following Greenhaus et al. (1989), flexibility was measured by two six-point Likert-type items, rated from “1 = strongly disagree” to “6 = strongly agree”. An illustrative item is “My work schedule is flexible”. The alpha coefficient was 0.798.

Family characteristics

Three different variables have been used to analyse family characteristics.

Family involvement

Items from the job involvement scale were modified in order to measure involvement in family roles. An illustrative item is “I am very much involved in my family role.” Thus, also in this case, four six-point Likert-type items have been used, rated from “1 = strongly disagree” to “6 = strongly agree”. The alpha coefficient was 0.785.

Parental demand

Slightly modifying Parasuraman and Simmers (2001), parental demands were measured by a scale derived from three questions relating to the presence or absence of children, the number of children, and the age of the children. The alpha coefficient was 0.755.

Time committed to family

Two self-reporting behaviourally anchored items were used, i.e. “In a working day, how much time do you spend on childcare?” and “In a working day, how much time do you spend on housework?” In both cases, the response categories included seven levels ranging from (l) “Less than 1 h” to (7) “More than 6 h”. The alpha coefficient was 0.864.

Social support

The social support the entrepreneur receives is measured by a self-reporting item that asked respondents: “How relevant is the support received from partner/family/services/networks?” Also in this case a six-point Likert-type item, rated from “1 = not important” to “6 = very important”, has been used in the survey.

Data analysis technique

In order to test the hypotheses, a structural equation modelling (SEM) methodology has been adopted. This methodology is the most suitable for the aim of this study as it allows investigation of multiple relationships (Bagozzi and Yi 2012; Bollen 1998). Among the variety of SEM models available, this study adopts the LISREL approach by using the lavaan software package for SEM implemented in the R system for statistical computing (R Development Core Team 2012) (Rosseel 2012). In particular, LISREL is the most suitable technique to be used for the purpose of this paper as it best fits with the analysis of large samples.

Before testing the identified hypotheses, the validity and reliability of the constructs have been checked by examining the Average Variance Extracted (AVE). The results are good as all the extracted AVE are higher than 0.5 (Fornell and Larcker 1981).

Findings

669 women entrepreneurs participated in this study. The largest percentage of the surveyed women is located in the North of the country (78.3%), is aged between 37 and 50 (52.2%), has a good level of education, as 48% of respondents have a secondary education and 31.4% have a degree, is in a couple (72.8%) and has at least one child (70%).

When working hours are taken into account (time committed to work), results show that 30% of the sampled women entrepreneurs spend a maximum of 40 h per week working, 58% devote between 40 and 60 h per week to working and 12% invest more than 60 h per week working. Regarding the time spent in family activities (time committed to family), our dataset is made up of women highly involved in their family activities, spending at least three hours per day on family oriented work.

Table 1 displays the overall fit indices of the four models. According to Tenenhaus et al. (2005) and Wetzels et al. (2009), these values are acceptable (Table 1).

Results from the bootstrapping are reported in Tables 2, 3 and 4.Footnote 1

Work domain stressors

According to Hypotheses 1a–b, 1c–d, 1e–f, three work domain stressors are hypothesized to be the predictors of WIF and FIW, namely job involvement, time committed to work and flexibility. Contrary to our Hypotheses 1a and 1e, job involvement and flexibility are not significantly related to WIF, while Hypothesis 1c is supported as Time committed to work is positively related to WIF (with a path coefficient equal to 0.091**). Hypotheses 1b and 1f are supported as job involvement and flexibility are significantly related to FIW with, respectively, a path coefficient equal to 0.123*** and −0.046***. Hypothesis 1d is not supported as time committed to work is not related to FIW.

Family domain stressors

Hypotheses 2a–b, 2c–d, 2e–f have been tested for the effects of family domain stressors on WIF and FIW. Results show that Hypotheses 2a and 2c are supported as family involvement and parental demand are significantly related to WIF with, respectively, a path coefficient equal to 0.107***, 0.131***. Although we found a significant effect of time committed to family (Hypothesis 2e) on WIF, it is a negative predictor (−0.018**), which is contrary to our hypothesis. Hypotheses 2b, 2d, 2f are supported, as family involvement, parental demand and time committed to family are significantly related to FIW with, respectively, a path coefficient equal to 0.125***, 0.110***, 0.043***.

Moderating effects of work and family supports

Hypotheses 3a, 3b, 3c and 3d predict that both work and family supports buffer the relationships between stressors and WIF and FIW. Results show that networking support does not moderate the relationship between work domain variables and WIF, thus Hypothesis 3a is not supported. Interestingly, support from the family domain (partner, family and private/public services) strongly moderate the relationship between family involvement and FIW, parental demand and FIW, as well as the relationship between time committed to family and FIW, thus supporting Hypotheses 3b, 3c and 3d.

A summary of standardized path coefficients for the four models is shown in Fig. 2.

Discussion

The present study has investigated the antecedents of WFC by analysing data from 669 Italian women entrepreneurs and by articulating WFC in two constructs, WIF and FIW. Based on previous research on employees’ WFC and applying it to women entrepreneurs, we developed main-effects hypotheses verifying both the within-domain and the cross-domain effects of work and family stressors on WIF and FIW experienced by women entrepreneurs. We also developed moderating-effects hypotheses, verifying whether social supports moderate each of the above mentioned linkages.

Overall, the results of this study suggest that both within-domain relationships and cross-domain relationships play a key role in explaining the work-family conflict experienced by women entrepreneurs. Results regarding the moderating-effects hypotheses offer substantial support for the notion that social supports within the family domain reduce the influence of family domain stressors on FIW while social support within the work domain does not moderate the relationship between work domain stressors and WIF.

This study makes three major contributions to the entrepreneurship literature. First, it responds to calls for more theoretical analyses on WFC in the field of entrepreneurship research, contributing to the unveiling of this relevant topic for a specific, under-investigated population in the literature, i.e. women entrepreneurs. Women entrepreneurs are indeed particularly exposed to WFC, due to their dual role in both family and business, whose consequences have been identified in low firm’s economic performance or in career dissatisfaction (e.g. Jennings and McDougald 2007; Shelton 2006). Second, differently from the majority of the few papers published on this subject, this study enriches the still scant conversation on the antecedents of WFC experienced by women entrepreneurs, rather than analysing WFC consequences. The analysis of WFC antecedents can, indeed, contribute to identify possible and more targeted actions to reduce the strain of WFC and thus reduce its highlighted negative consequences. Third, stemming from the most updated results in the employees’ literature, this study proposes an extended model of WFC experienced by women entrepreneurs, hypothesizing both within- and cross-domain relationships between family/work stressors and WIF and FIW, in order to take a step further in the comprehension of the intertwinement of family and work.

In particular, regarding the main-effects hypotheses, results show that, contrary to the most consolidated findings in the employees’ literature, work stressors are mainly predictors of FIW rather than WIF. Regarding the family stressors, they are predictors of both FIW and WIF, although the within-domain relationships are stronger than the cross-domain ones, thus confirming the consolidated findings emerging from studies on employees that historically support the within-domain relationships.

These results clearly point out how much family and work are strongly interrelated for women entrepreneurs. In particular, results on work stressors can be understood by considering the relevant role that work plays in women entrepreneurs’ life, which allows them not to perceive it as something that will interfere with family but as a means of satisfaction and personal fulfilment. Accordingly, the work stressors “job involvement” and “flexibility” are not significantly related to WIF as, for these women, work is not a burden to face. At the same time, family also plays a crucial role in women entrepreneurs’ life and, consequently, time devoted to work can be read as time subtracted from family, thus justifying the positive and significant relationships between time committed to work and WIF. In explaining the results, the context on which these women entrepreneurs are grounded cannot be overlooked. In Europe, and in particular in South Europe, it is still widespread that women assume the main caring and domestic roles, while men are considered the main “breadwinners” who can devote more time to paid employment. Such a “job division” between men and women strongly influences the societal legitimation of women to act as entrepreneurs and to work hard and for long hours to achieve their professional goals. Consistently, regarding the cross-domain relationships between work stressors and FIW, as flexibility increases, it is easier for women entrepreneurs to satisfy family demands, thus FIW decreases. Moreover, regarding the relationship between job involvement and FIW, it can be explained by considering the different degrees of involvement a person has with his/her work. If it is true that, in the case of employees (and especially when dealing with low-skilled jobs), the end of the daily working hours very often also corresponds to the end of job-related concerns, the situation radically changes when referring to women entrepreneurs. In this case, the two domains can hardly be considered completely separate (Aldrich and Cliff 2003). Managing a firm requires not only a greater time commitment, but also generally involves responsibilities that do not finish with the end of the standard daily working hours. This intertwinement between the two domains consequently generates the fact that entrepreneurs have greater difficulty in separating work from family (two equally important life spans) in terms of involvement. Accordingly, the problem cannot be identified in the number of hours women devote to work but their level of job involvement. Thus, it not surprising that time committed to work is not related to FIW.

Results on family stressors are consistent with results on work stressors. With regard to the within-domain relationships, this paper’s results show that women entrepreneurs who reported higher levels of family involvement, of parental demand and of time committed to family, experience higher levels of FIW. These results can be explained by considering that the majority of family responsibilities (in terms of family care and time devoted to housework) are, indeed, women’s burdens. Along this rationale, explanations for the cross-domain relationships can be offered. On the one hand, results regarding family involvement are symmetrical to those related to job involvement: the intertwining between the two spheres is so high that it is particularly difficult to separate the two domains. On the other hand, in this scenario, results on parenting demand are not surprising as women still play the key role in childcare. More intriguingly, the negative relationship between time committed to family and WIF does not support our hypothesis but it is consistent with Parasuraman et al.’s (1996) results. Such a negative relationship can be explained by taking into consideration the individual’s perception of the burden deriving from family demands: if the time devoted to family increases, WIF decreases because the woman entrepreneur is performing a central task, a task she cannot avoid. Longitudinal research that analyses the different stages of women entrepreneurs’ life is recommended to test the merit of this possible explanation.

By considering the moderating effects of social supports, our study extends prior results, suggesting that moderators should be included in the model for a better understanding of the complexities of the WFC experienced by women entrepreneurs. Our results point out that social supports in the family domain can help buffer the negative consequences of family domain stressors on FIW. These results are in line with previous works on employees (e.g. Chang et al. 2014). In contrast, social support in the work domain does not moderate the influence of work domain variables on WIF. Two possible explanations are offered. On the one hand, women entrepreneurs in Italy, and worldwide (e.g. Jennings and Brush 2013), generally have low access to relevant (especially professional) networks (e.g. Mari et al. 2016). On the other hand, the type of social support measures may have influenced the results.

Results from this paper allow us to point out a number of practical implications for women entrepreneurs, for academics and for policy makers.

In relation to women entrepreneurs, these findings can contribute to shed light on the relevance of WFC-related issues. Future and already established women entrepreneurs must realistically understand how much time they are able to devote to their business, how much time they are able to devote to their family, and which social supports they can count on in order to identify appropriate strategies to manage the conflict.

Policy makers could take advantage of these results by using them in order to plan specific training courses both for nascent and consolidated entrepreneurs, through which people would be educated not only to be aware of the existence of WFC, but also stimulated into finding ways to manage, in an effective way, competing work and family demands.

Finally, given the relevance of (women) entrepreneurs, it is crucial to understand that the WFC is not related only to employees and that it is not an individual responsibility, but rather a problem that needs to be addressed, in society, at an institutional level. Academics can play a key role by analysing the most relevant variables able to cause WFC for women entrepreneurs so that individuals and policy makers can work on those variables.

Limitations

The present study has limitations that should be noted.

First, the antecedents selected for this analysis are not completely exhaustive of all the antecedents of WFC. Those selected have been chosen as the most used in published reviews of WFC and in papers regarding WFC as the most suitable to explain the investigated phenomenon; unfortunately, it is not possible to measure all the possible antecedents of WFC in a single work so that an a priori choice had to be made. Second, for the current study we did not ask women entrepreneurs if they have experience of caring for aging family members. As this topic is particularly relevant in modern society, it should be considered in future studies. Third, in the survey a definition of “family” has not been provided. As Powell and Eddleston (2013) underline, citing Aldrich and Cliff (2003), “the nature of families is evolving” (p. 278); accordingly, a clear definition of “family” should be given to respondents. Fourth, data were collected from women entrepreneurs grounded in Italy, and the analysis of the sample has shown that respondents were mainly located in the northern regions of the country. Samples from other regions of the same nation or from different nations could provide different results, as regional or national cultures can influence some of the mechanisms investigated in this paper. As an example, individualistic cultures (e.g. USA and Italy) keep work and family relationships separate, whereas collectivistic cultures (e.g. China) better integrate the two domains (Hofstede 1989).

Conclusions

The WFC topic has become increasingly relevant in academia over the past 20 years, but research has mainly investigated individuals who are organizationally employed. Only recently have researchers considered WFC as an important issue for entrepreneurs but the effort devoted to women entrepreneurs is still scant. In this scenario, this study extends prior research by examining the antecedents of WFC experienced by women entrepreneurs, thus definitely contributing to reducing the existing voids in this topic. In particular, our results point out how important it is to consider both the within- and the cross-domain relationships when the antecedents of WFC are studied, due to the impossibility to separate the family and work domains.

Future research should continue to investigate WFC experienced by women entrepreneurs and, stemming from the results presented above, a foundation for future research and practice emerges.

First, individual level variables, such as those related to personality factors, as well as new moderators or new measures for those already selected should be included in future studies to better consolidate results. Second, longitudinal analyses on WFC, based on the assumption that women entrepreneurs’ WFCs change over the life-cycle of the woman entrepreneur, could provide interesting information in order to develop targeted policies able to mitigate the conflicts according to the specific life-cycle stage of the entrepreneur. Third, interesting results could also derive from pushing the analysis of the potential positive side of the work-family interface (Powell and Eddleston 2013).

Notes

*, **, *** significant at 0.10, 0.05 and 0.01 level, respectively.

References

Adams, G. A., King, L. A., & King, D. W. (1996). Relationships of job and family involvement, family social support, and work-family conflict with job and life satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(4), 411–420. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.81.4.411.

Aldrich, H. E., & Cliff, J. E. (2003). The pervasive effects of family on entrepreneurship: Toward a family Embeddedness perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(5), 573–596. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00011-9.

Amstad, F. T., Meier, L. L., Fasel, U., Elfering, A., & Semmer, N. K. (2011). A meta-analysis of work-family conflict and various outcomes with a special emphasis on cross-domain versus matching-domain relations. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 16(2), 151–169. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022170.

Anatan, L. (2013). A proposed conceptual framework of work-family/family-work facilitation (wff/fwf) approach in inter-role conflict. Journal of Global Management, 6(1), 89–100.

Anderson, S. E., Coffey, B. S., & Byerly, R. T. (2002). Formal organizational initiatives and informal workplace practices: Links to work-family conflict and job-related outcomes. Journal of Management, 28(6), 787–810.

Annink, A., & den Dulk, L. (2012). Autonomy: The panacea for self-employed women's work-life balance? Community, Work & Family, 15(4), 383–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2012.723901.

Aryee, S., Luk, V., Leung, A., & Lo, S. (1999). Role stressors, interrole conflict, and well-being: The moderating influence of spousal support and coping behaviors among employed parents in Hong Kong. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 54(2), 259–278. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1998.1667.

Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (2012). Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(1), 8–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0278-x.

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Dollard, M. F. (2008). How job demands affect partners' experience of exhaustion: Integrating work-family conflict and crossover theory. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(4), 901–911. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.4.901.

Batt, R., & Valcour, P. M. (2003). Human resources practices as predictors of work-family outcomes and employee turnover. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 42(2), 189–220.

Baugh, S. G., Hunt, J. G., & Scandura, T. A. (2006). Reviewing by the numbers: Evaluating quantitative research. In Y. Baruch, S. E. Sullivan, & H. N. Schepmyer (Eds.), Winning reviews: A guide for evaluating scholarly writing (pp. 156–172). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Beigi, M., Mirkhalilzadeh Ershadi, S., & Shirmohammadi, M. (2012). Work-family conflict and its antecedents among Iranian operating room personnel. Management Research Review, 35(10), 958–973. https://doi.org/10.1108/01409171211272688.

Bellavia, G., & Frone, M. (2005). Work-family conflict. In J. Barling, E. K. Kelloway, & M. Frone (Eds.), Handbook of work stress. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412975995.n6.

Berg, P., Appelbaum, E., Bailey, T., & Kalleberg, A. L. (2004). Contesting time: International comparisons of employee control of working time. ILR Review, 57(3), 331–349. https://doi.org/10.1177/001979390405700301.

Beutell, N., Schneer, A., & J. (2014). Work-family conflict and synergy among Hispanics. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 29(6), 705–735. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-11-2012-0342.

Biddle, B. J. (1986). Recent developments in role theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 12(1), 67–92. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.12.080186.000435.

Bohen, H., & Viveros-Long, A. (1981). Balancing jobs and family life. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Bollen, K. A. (1998). Structural equation models. New York: Wiley.

Boyar, S. L., & Mosley, D. C. (2007). The relationship between core self-evaluations and work and family satisfaction: The mediating role of work-family conflict and facilitation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 71(2), 265–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2007.06.001.

Byron, K. (2005). A meta-analytic review of work-family conflict and its antecedents. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67(2), 169–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2004.08.009.

Calvo-Salguero, A., Martínez-de-Lecea, J. M. S., & del Carmen Aguilar-Luzón, M. (2012). Gender and work-family conflict: Testing the rational model and the gender role expectations model in the Spanish cultural context. International Journal of Psychology, 47(2), 118–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207594.2011.595414.

Carlson, D. S., & Perrewe, P. L. (1999). The role of social support in the stressor-strain relationship: An examination of work-family conflict. Journal of Management, 25(4), 513–540. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639902500403.

Chang, A., Chen, S. C., & Chi, S. C. S. (2014). Role salience and support as moderators of demand/conflict relationships in China. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 23(6), 859–874. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2013.821739.

Chrisman, J. J., Chua, J. H., & Sharma, P. (2005). Trends and directions in the development of a strategic management theory of the family firm. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(5), 555–576. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2005.00098.x.

Dewberry, C. (2004). Statistical methods for organizational research: Theory and practice. Psychology Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203414897.

Dilworth, J. E. L. (2004). Predictors of negative spillover from family to work. Journal of Family Issues, 25(2), 241–261. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X03257406.

Duxbury, L. E., & Higgins, C. A. (2001). Work-life balance in the new millennium: Where are we? Where do we need to go? (Vol. 4). Ottawa, ON: Canadian Policy Research Networks.

Edwards, J. R., & Rothbard, N. P. (2000). Mechanisms linking work and family: Clarifying the relationship between work and family constructs. Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 178–199.

Fahlén, S. (2014). Does gender matter? Policies, norms and the gender gap in work-to-home and home-to-work conflict across Europe. Community, Work & Family, 17(4), 371–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2014.899486.

Fassott, G., Fassott, G., Henseler, J., Henseler, J., Coelho, P. S., & Coelho, P. S. (2016). Testing moderating effects in PLS path models with composite variables. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(9), 1887–1900. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-06-2016-0248.

Ford, M. T., Heinen, B. A., & Langkamer, K. L. (2007). Work and family satisfaction and conflict: A meta-analysis of cross-domain relations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(1), 57–80. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.1.57.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312.

Forson, C. (2013). Contextualising migrant black business women's work-life balance experiences. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, 19(5), 460–477. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-09-2011-0126.

Friedman, S. D., & Greenhaus, J. H. (2000). Work and family – Allies or enemies? What happens when business professionals confront life choices. USA: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195112757.001.0001.

Frone, M. R. (2003). Work-family balance. In J. C. Quick & L. E. Tetrick (Eds.), Handbook of Occupational Health Psychology (pp. 143–162). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Frone, M. R., & Yardley, J. K. (1996). Workplace family-supportive programmes: Predictors of employed parents' importance ratings. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 69(4), 351–366. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1996.tb00621.x.

Frone, M. R., Russell, M., & Cooper, M. L. (1992a). Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict: Testing a model of the work-family Interface. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77(1), 65–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.77.1.65.

Frone, M. R., Russell, M., & Cooper, M. L. (1992b). Prevalence of work-family conflict: Are work and family boundaries asymmetrically permeable? Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13(7), 723–729. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030130708.

Frone, M. R., Yardley, J. K., & Markel, K. S. (1997). Developing and testing an integrative model of the work-family Interface. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 50(2), 145–167. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1996.1577.

Fu, C. K., & Shaffer, M. A. (2001). The tug of work and family: Direct and indirect domain-specific determinants of work-family conflict. Personnel Review, 30(5), 502–522. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000005936.

Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Consortium. (2017), GEM Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Global Reports, 2016. http://www.gemconsortium.org/. Accessed 2 October 2017.

Greenhaus, J.H., & Allen, T.D. (2011). Work–family balance: A review and extension of the literature, in Quick, J. C. E., & Tetrick, L. E.(Eds.), Handbook of occupational health psychology (pp. 165-183). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Greenhaus, J. H., & Beutell, N. J. (1985). Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review, 10(1), 76–88.

Greenhaus, J. H., & Kopelman, R. E. (1981). Conflict between work and nonwork roles: Implications for the career planning process. Human Resource Planning, 4(1), 1–10.

Greenhaus, J. H., & Parasuraman, S. (1999). Research on work, family, and gender: Current status and future direction. In G. N. Powell (Ed.), Handbook of gender and work (pp. 391–412). Newbury Park: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452231365.n20.

Greenhaus, J. H., Bedeian, A. G., & Mossholder, K. W. (1987). Work experiences, job performance, and feelings of personal and family well-being. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 31(2), 200–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-8791(87)90057-1.

Greenhaus, J. H., Parasuraman, S., Granrose, C. S., Rabinowitz, S., & Beutell, N. J. (1989). Sources of work-family conflict among two-career couples. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 34(2), 133–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-8791(89)90010-9.

Grzywacz, J. G., & Marks, N. F. (2000). Reconceptualizing the work-family interface: An ecological perspective on the correlates of positive and negative spillover between work and family. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(1), 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.5.1.111.

Grzywacz, J., Almeida, D., & McDonald, D. A. (2002). Work-family spillover and daily reports of work and family stress in the adult labor force. Family Relations, 51(1), 28–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2002.00028.x.

Gutek, B. A., Searle, S., & Klepa, L. (1991). Rational versus gender role explanations for work-family conflict. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76(4), 560–568. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.76.4.560.

Hammer, L. B., Neal, M. B., Newson, J. T., Brockwood, K. J., & Colton, C. L. (2005). A longitudinal study of the effects of dual-earner couples’ utilization of family-friendly workplace supports on work and family outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(4), 799–810. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.4.799.

Hampton, A., Cooper, S., & Mcgowan, P. (2009). Female entrepreneurial networks and networking activity in technology-based ventures: An exploratory study. International Small Business Journal, 27(2), 193–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242608100490.

Hargis, M. B., Kotrba, L. M., Zhdanova, L., & Baltes, B. B. (2011). What's really important? Examining the relative importance of antecedents to work-family conflict. Journal of Managerial Issues, 23(4), 386–408.

Hill, E. J. (2005). Work-family facilitation and conflict, working fathers and mothers, work-family stressors and support. Journal of Family Issues, 26(6), 793–819. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X05277542.

Hofstede, G. (1989). Organising for cultural diversity. European Management Journal, 7(4), 390–397. https://doi.org/10.1016/0263-2373(89)90075-3.

Holahan, C. K., & Gilbert, L. A. (1979). Interrole conflict for working women: Careers versus jobs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 64(1), 86–90. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.64.1.86.

House, J. S. (1981). Work stress and social support. Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co..

Jacobs, J. A., & Gerson, K. (2004). The time divide: Work, family, and gender inequality. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Jennings, J. E., & Brush, C. G. (2013). Research on women entrepreneurs: Challenges to (and from) the broader entrepreneurship literature? Academy of Management Annals, 7(1), 663–715. https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520.2013.782190.

Jennings, J. E., & McDougald, M. S. (2007). Work-family interface experiences and coping strategies: Implications for entrepreneurship research and practice. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 747–760. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2007.25275510.

Kanungo, R. N. (1982a). Work alienation and involvement: Problems and prospects. International Review of Applied Psychology, 30(1), 1–15.

Kanungo, R. N. (1982b). Measurement of job and work involvement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 67(3), 341–349. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.67.3.341.

Kelly, E. L., Moen, P., & Tranby, E. (2011). Changing workplaces to reduce work-family conflict: Schedule control in a white-collar organization. American Sociological Review, 76(2), 265–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122411400056.

Kinman, G., & Jones, F. (2008). Effort-reward imbalance, over-commitment and work-life conflict: Testing an expanded model. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 23(3), 236–251. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940810861365.

Kinnunen, U., & Mauno, S. (1998). Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict among employed women and men in Finland. Human Relations; Studies Towards the Integration of the Social Sciences, 51(2), 157–177. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679805100203.

Kinnunen, U., Feldt, T., Geurts, S., & Pulkkinen, L. (2006). Types of work-family interface: Well-being correlates of negative and positive spillover between work and family. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 47(2), 149–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9450.2006.00502.x.

Kirkwood, J., & Tootell, B. (2008). Is entrepreneurship the answer to achieving work-family balance? Journal of Management & Organization, 14(3), 285–302.

Kossek, E. E., & Ozeki, C. (1998). Work-family conflict, policies, and the job life satisfaction relationship: A review and directions for organizational behavior-human resources research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(2), 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.83.2.139.

Kossek, E. E., Lautsch, B. A., & Eaton, S. C. (2006). Telecommuting, control, and boundary management: Correlates of policy use and practice, job control, and work-family effectiveness. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68(2), 347–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2005.07.002.

Kossek, E. E., Pichler, S., Bodner, T., & Hammer, L. B. (2011). Workplace social support and work-family conflict: A meta-analysis clarifying the influence of general and work-family-specific supervisor and organizational support. Personnel Psychology, 64(2), 289–313. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2011.01211.x.

Lapierre, L. M., & Allen, T. D. (2006). Work-supportive family, family supportive supervision, use of organizational benefits, and problem-focused coping: Implications for work-family conflict and employee well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 11(2), 169–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.11.2.169.

Lawrence, S. A. (2006). An integrative model of perceived available support, work-family conflict and support mobilisation. Journal of Management & Organization, 12(2), 160–178.

Lee Siew Kim, J., & Seow Ling, C. (2001). Work-family conflict of women entrepreneurs in Singapore. Women in Management Review, 16(5), 204–221. https://doi.org/10.1108/09649420110395692.

Lee, N., Zvonkovic, A. M., & Crawford, D. W. (2014). The impact of work-family conflict and facilitation on women’s perceptions of role balance. Journal of Family Issues, 35(9), 1252–1274. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X13481332.

Lingard, H., Francis, V., & Turner, M. (2012). Work time demands, work time control and supervisor support in the Australian construction industry: An analysis of work-family interaction. Engineering Construction and Architectural Management, 19(6), 647–665. https://doi.org/10.1108/09699981211277559.

Loscocco, K. A. (1997). Work-family linkages among self-employed women and men. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 50(2), 204–226. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1996.1576.

Loscocco, K., & Bird, S. R. (2012). Gendered paths: Why women lag behind men in small business success. Work and Occupations, 39(2), 183–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888412444282.

Loscocco, K. A., Robinson, J., Hall, R. H., & Allen, J. K. (1991). Gender and small business success: An inquiry into women’s relative disadvantage. Social Forces, 70(1), 65–85. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/70.1.65.

Lu, L., Gilmour, R., Kao, S. F., & Huang, M. T. (2006). A cross-cultural study of work/family demands, work/family conflict and wellbeing: The Taiwanese vs British. Career Development International, 11(1), 9–27. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430610642354.

Luk, D. M., & Shaffer, M. A. (2005). Work and family domain stressors and support: Within- and cross-domain influences on work–family conflict. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 78(4), 489–508. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317905X26741.

Mari, M., Poggesi, S., & De Vita, L. (2016). Family embeddedness and business performance: Evidences from women-owned firms. Management Decision, 52(2), 476–500.

Marks, S. R. (1977). Multiple roles and role strain: Some notes on human energy, time and commitment. American Sociological Review, 42(6), 921–936. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094577.

Matsui, T., Ohsawa, T., & Onglatco, M. L. (1995). Work-family conflict and the stress-buffering effects of husband support and coping behavior among Japanese married working women. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 47(2), 178–192. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1995.1034.

McGinnity, F., & Calvert, E. (2009). Work-life conflict and social inequality in Western Europe. Social Indicators Research, 93(3), 489–508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-008-9433-2.

McNall, L. A., Nicklin, J. M., & Masuda, A. D. (2010). A meta-analytic review of the consequences associated with work-family enrichment. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25(3), 381–396. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-009-9141-1.

Mesmer-Magnus, J. R., & Viswesvaran, C. (2005). Convergence between measures of work-to-family and family-to-work conflict: A meta-analytic examination. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67(2), 215–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2004.05.004.

Michel, J. S., & Clark, M. A. (2009). Has it been affect all along? A test of work-to-family and family-to-work models of conflict, enrichment, and satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 47(3), 163–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.02.015.

Michel, J. S., Kotrba, L. M., Mitchelson, J. K., Clark, M. A., & Baltes, B. B. (2011). Antecedents of work-family conflict: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32(5), 689–725. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.695.

Mitchell, T. R. (1985). An evaluation of the validity of correlational research conducted in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 10(2), 192–205.

Moore, J. E. (2000). Why is this happening? A causal attribution approach to work exhaustion consequences. Academy of Management Review, 25(2), 335–349.

Netemeyer, R. G., McMurrian, R., & Boles, J. S. (1996). Development and validation of work-family conflict and family-work conflict scales. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(4), 400–410. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.81.4.400.

Ng, L. P., Kuar, L. S., & Cheng, W. H. (2016). Influence of work-family conflict and work-family positive spillover on healthcare professionals’ job satisfaction. Business Management Dynamics, 5(11), 1–15.

Nguyen, H., & Sawang, S. (2016). Juggling or struggling? Work and family interface and its buffers among small business owners. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 6(2), 207–246.

Nielson, T. R., Carlson, D. S., & Lankau, M. J. (2001). The supportive mentor as a means of reducing work-family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 59(3), 364–381. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2001.1806.

Nohe, C., Meier, L. L., Sonntag, K., & Michel, A. (2015). The chicken or the egg? A meta-analysis of panel studies of the relationship between work-family conflict and strain. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(2), 522–536. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038012.

Noor, N. (2004). Work-family conflict, work- and family-role salience and women’s well-being. Journal of Social Psychology, 144(4), 389–405. https://doi.org/10.3200/SOCP.144.4.389-406.

Parasuraman, S., & Simmers, C. A. (2001). Type of employment, work-family conflict and wellbeing: A comparative study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22(5), 551–568. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.102.

Parasuraman, S., Purohit, Y. S., Godshalk, V. M., & Beutell, N. J. (1996). Work and family variables, entrepreneurial career success, and psychological well-being. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 48(3), 275–300. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1996.0025.

Pocock B., Skinner, N. & Williams, P (2007). Work, life and time. The Australian Work and Life Index.

Podsakoff, P. M., & Organ, D. W. (1986). Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. Journal of Management, 12(4), 531–544. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920638601200408.

Poggesi, S., Mari, M., & De Vita, L. (2016). What’s new in female entrepreneurship research? Answers from the literature. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 12(3), 735–764

Powell, G. N., & Eddleston, K. A. (2013). Linking family-to-business enrichment and support to entrepreneurial success: Do female and male entrepreneurs experience different outcomes? Journal of Business Venturing, 28(2), 261–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2012.02.007.

Rehman, S., & Azam Roomi, M. (2012). Gender and work-life balance: A phenomenological study of women entrepreneurs in Pakistan. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 19(2), 209–228. https://doi.org/10.1108/14626001211223865.

Robichaud, Y., Zinger, J. T., & LeBrasseur, R. (2007). Gender differences within early stage and established small enterprises: An exploratory study. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 3(3), 323–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-007-0039-y.

Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36.

Schieman, S., Milkie, M. A., & Galvin, P. (2009). When work interferes with life: Work-nonwork interference and the influence of work-related demands and resources. American Sociological Review, 74(6), 966–988. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240907400606.

Shelton, L. M. (2006). Female entrepreneurs, work-family conflict, and venture performance: New insights into the work-family interface. Journal of Small Business Management, 44(2), 285–297. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2006.00168.x.

Shockley, K. M., & Allen, T. D. (2007). When flexibility helps: Another look at the availability of flexible work arrangements and work-family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 71(3), 479–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2007.08.006.

Shockley, K. M., & Singla, N. (2011). Reconsidering work—Family interactions and satisfaction: A meta-analysis. Journal of Management, 37(3), 861–886. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310394864.

Stoner, C. R., Hartman, R. I., & Arora, R. (1990). Work-home role conflict in female owners of small businesses: An exploratory study. Journal of Small Business Management, 28(1), 30–38.

Sullivan, D. M., & Meek, W. R. (2012). Gender and entrepreneurship: A review and process model. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 27(5), 428–458. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683941211235373.

Tenenhaus, M., Vinzi, V. E., Chatelin, Y. M., & Lauro, C. (2005). PLS path modeling. Computational Statistics and Data Analysis, 48(1), 159–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csda.2004.03.005.

Teo, S. T., Newton, C., & Soewanto, K. (2013). Context-specific stressors, work-related social support and work-family conflict: A mediation study. New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 38(1), 14.

Tews, M. J., Noe, R. A., Scheurer, A. J., & Michel, J. W. (2016). The relationships of work-family conflict and core self-evaluations with informal learning in a managerial context. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 89(1), 92–110. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12109.

Thomas, L. T., & Ganster, D. C. (1995). Impact of family-supportive work variables on work-family conflict and strain: A control perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 80(1), 6–15. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.80.1.6.

Valcour, M. (2007). Work-based resources as moderators of the relationship between work hours and satisfaction with work-family balance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(6), 1512–1523. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.6.1512.

Vieira, J. M., Matias, M., Lopez, F. G., & Matos, P. M. (2016). Relationships between work–family dynamics and parenting experiences: A dyadic analysis of dual-earner couples. Work and Stress, 30(3), 243–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2016.1211772.

Viswesvaran, C., Sanchez, J. I., & Fisher, J. (1999). The role of social support in the process of work stress: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 54(2), 314–334. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1998.1661.

Voydanoff, P. (2004). The effects of work demands and resources on work-to-family conflict and facilitation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66(2), 398–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2004.00028.x.

Wetzels, M., Odekerken-Schröder, G., & Van Oppen, C. (2009). Using PLS path modeling for assessing hierarchical construct models: Guidelines and empirical illustration. MIS Quarterly, 177–195.

Winn, J. (2005). Women entrepreneurs: Can we remove the barriers? International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 1(3), 381–397. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-005-2602-8.

Zhang, M., Griffeth, R. W., & Fried, D. D. (2012). Work-family conflict and individual consequences. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 27(7), 696–713. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683941211259520.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Poggesi, S., Mari, M. & De Vita, L. Women entrepreneurs and work-family conflict: an analysis of the antecedents. Int Entrep Manag J 15, 431–454 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-017-0484-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-017-0484-1